Issue

Australia is currently facing a housing crisis, with the affordability of

house purchase or rental deteriorating over several decades. The National Housing Supply and Affordability Council

(2025) notes

that, in 2024 the average number of years

required to save for a deposit ‘rose to a near-record high of 10.6 years, and

the ratio of dwelling prices to income rose to 8.0’ (p.3). As a complex issue

with no simple solutions, Australia’s housing crisis has become a ‘wicked

problem’ for policymakers at all levels of government.

Through a short overview of who is responsible for what in

several key areas of housing policy in Australia, this policy brief

demonstrates that in most areas the Commonwealth is generally a ‘minor player’

in housing policy in Australia.

Key

points

- The

Australian Constitution assigns specific legislative powers to the

Commonwealth, with residual powers, including housing, falling to the states.

As a result, housing is primarily a state responsibility, and the

Commonwealth plays an indirect role.

- While

the Commonwealth lacks direct legislative authority over areas such as

residential tenancies, land-use planning and building standards, it can lead

and support national coordination on these issues.

- The

Commonwealth’s inability to regulate housing policy means that key aspects of

the housing crisis in Australia remain the responsibility of the states and

territories to resolve, either alone or in collaboration with each other, or

with the Commonwealth.

Constitutional

limitations and the Commonwealth

Section

51 of the Constitution

outlines most of the Commonwealth's legislative powers, but does not grant the

Commonwealth a general power over housing matters like residential tenancies or

zoning laws. Legislative powers not explicitly

granted to the Commonwealth remain

with the states. As such, the states hold the primary position to act on various

housing issues (with some authority delegated to local governments).

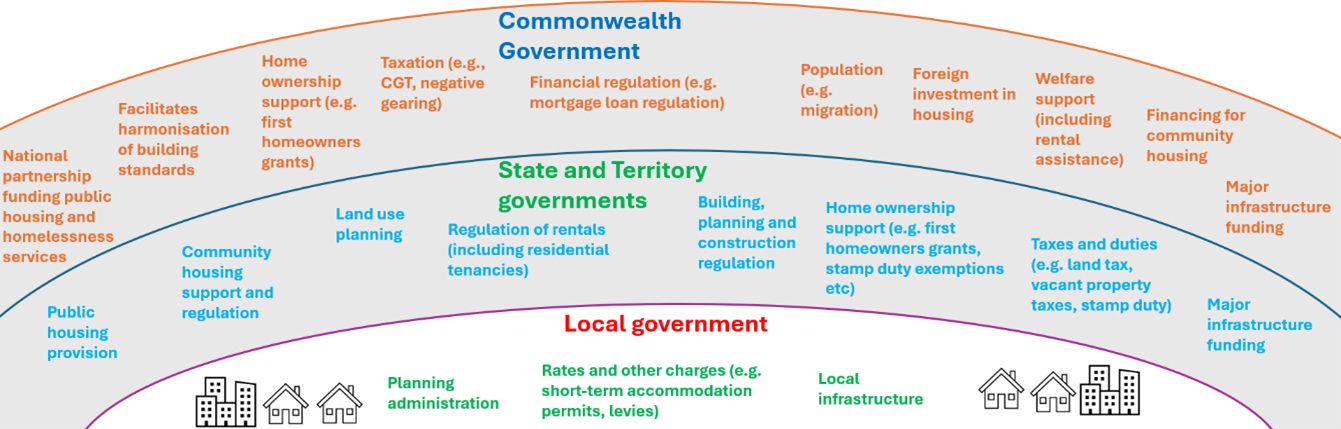

The image below (Figure 1) summarises the current areas of

responsibility for regulating various housing policy aspects, which largely

reflects existing constitutional arrangements.

Figure 1: Division of regulatory and policy implementation

responsibility over housing

Source: adapted by the Parliamentary Library from Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, Submission to the Senate Standing Committee Inquiry into the

worsening rental crisis in Australia, p. 22

The regulation

of residential tenancies, taxation, land planning, and housing construction are

examined briefly below. For further information about rental affordability

issues in Australia please refer to the Parliamentary Library’s Issues and

Insights article Implications

of Declining Home Ownership.

Residential tenancies

Regulating rents and residential tenancy laws

It has long been acknowledged that outside

of wartime (pp 2-3) the Commonwealth lacks a direct legislative power over

residential tenancies, a limitation highlighted by the unsuccessful

1948

Rents and Prices referendum. However, this does not mean that the states

and territories could not collaborate amongst

themselves, or with

the Commonwealth, to achieve uniform residential tenancy laws. In addition,

the Commonwealth could attempt to regulate a proportion of residential

tenancies, under certain constitutional powers as noted below.

Ultimately

however, the states remain responsible for regulating rents, and the

Commonwealth lacks the clear authority to impose a ‘rent cap’ on (or otherwise

regulate) all residential tenancies, as that power remains with the

states.

Regulating corporate housing market participants

The Constitution

provides the Commonwealth the power to make laws with respect to constitutional

corporations, including any relationships they have

with third parties (pp. 8, 16–17,20). This

means the corporations power could potentially support legislation

regulating constitutional corporations that are residential

landlords or offer residential property management services.

This may include regulating relationships that constitutional

corporations have with landlords and

tenants. However, it would not allow the Commonwealth to regulate

natural persons without any relationships with a constitutional corporation

(e.g. individuals who self-manage their rental properties).

The external affairs power and the human right to

adequate housing

The Constitution

permits the Commonwealth to legislate on matters arising from international

treaties Australia has ratified in some situations. Under Article 11 of the

United Nations’ International

Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), Australia must

recognise and take ‘appropriate steps’ toward the right to ‘adequate’ housing. This may include

taking

appropriate legislative or other measures to regulate housing and rental

markets in ways that promote that right (p 33).

It has been argued

that the ICESCR could support Commonwealth legislation on residential tenancies

under the external affairs power. However, any such legislation —such as rental

caps—would need to be reasonably

appropriate and adapted (paragraphs [33]-[34]) to promoting

the right to adequate housing as understood under the ICESCR, not the broader

housing market. Furthermore, such a law’s constitutionality would ultimately rest

with the High Court.

Taxation of housing and related issues

All levels of government have

various powers to impose various types of taxes and charges in relation to

housing. For example:

The Commonwealth's broad and flexible taxation power ‘extends

to any form of tax that ingenuity may devise’ ([90-1355]), provided the tax

laws do not discriminate between States or parts of

States. They can, however, potentially override (to the extent of any

inconsistency) state taxes under section

109 of the Constitution. This allows the Commonwealth to implement

diverse housing-related tax initiatives, including new taxes like vacant

property taxes.

In addition to creating new types of taxes, the Commonwealth

can also modify or abolish existing taxes on housing. For example, the

Commonwealth could modify how rental income is taxed by altering rules on

deductions, negative

gearing, capital gains tax discounts or exemptions and tax rates. Such changes could be designed to encourage investment in housing construction through reducing associated tax costs.

The states and local governments could also, absent any Commonwealth

initiatives, also modify their taxes and charges to achieve similar outcomes.

Shaping the built environment

Planning the location and character of housing

State governments are constitutionally responsible for

land-use planning. All states have land-use planning legislation and, as Ruming

et al. (2014) note, they have been ‘careful to maintain’ their authority.

Conversely, the Commonwealth plays an indirect role in shaping development, regulating

land-use only in very limited circumstances. For instance, the Commonwealth

regulates matters of ‘national

environmental significance’ (such as World Heritage sites) using its constitutional

external

affairs power (section

51(xxix) of the Constitution). Section

52 of the Constitution also grants it authority over planning and

managing most Commonwealth land.

Since

World War II, the Commonwealth has primarily influenced housing through

conditional grants to the states under section

96 of the Constitution. This includes

national housing agreements and infrastructure funding, such as the Housing

Australia Future Fund (HAFF) established on 1

November 2023 by the Housing

Australia Future Fund Act 2023 (HAFF Act). Through the

HAFF, Housing Australia provides funding to states and territories for eligible

social and affordable housing projects.

In recent years, the Commonwealth has taken a more active

leadership role in land-use planning, with

varying levels of engagement. Key initiatives include:

The Commonwealth has also sought to ‘flex

its fiscal muscle’ by tying infrastructure funding to urban planning

standards. For example, a 2009

Council of Australian Governments (COAG) agreement introduced nine national

criteria for capital city strategic planning. This agreement committed that ‘…by

1 January 2012 all States will have in place plans that meet the criteria’ and

noted that ‘the Commonwealth will link future infrastructure funding decisions

to meeting these criteria.’

Commentators (for instance, Ruming et al.) have observed

that post-2009 capital city planning policies explicitly referenced the

national criteria, leading to the conclusion that the criteria likely had more

influence on planning policy than the Commonwealth’s 2011 National

Urban Policy (which lacked an implementation mechanism). Accordingly:

If competition between jurisdictions for

status of best capital city planning framework operated as a policy carrot to

encourage the overt adoption of the national criteria, the risk of reduced

national infrastructure funding operated as an implied policy stick. (Ruming

et al., p.115)

Harmonising building standards

State and territory governments are responsible for the safety,

health, and amenity of construction. While it has no formal role, the

Commonwealth coordinates nationally consistent building standards, through

consensus with the states.

The National Construction

Code (NCC) is a set of uniform technical requirements for building design

and construction across Australia. It is given legal effect through state and

territory legislation (for instance, the Environmental

Planning and Assessment Act 1979 and the Plumbing

and Drainage Act 2011 in NSW) and is updated

every three years based on industry research, public feedback, and

government policy.

The NCC is overseen by the Building

Ministers’ Meeting, which includes state and territory ministers

responsible for building and plumbing regulation. The NCC is published and

maintained by the Australian Building Codes

Board (ABCB), an agency within the Department

of Industry, Science and Resources. Established

in 1994 by an Inter-Government

Agreement (IGA), the ABCB reports to the Building Ministers’ Meeting and is

supported by the ABCB Office.

The most

recent (2020) IGA affirms that the states and territories are primarily

responsible for building and construction (Section 1.2) but highlights the

importance of national consistency. The IGA’s stated goal is to improve

building outcomes, boost public confidence, and enhance the building industry’s

efficiency and global competitiveness (Section 1.1).

What does this mean for the housing market?

Regulatory responsibility for the housing market as a whole

is fragmented between the three levels of government in Australia. Whilst the

Commonwealth is able to provide leadership and coordinate policy responses in

relation to housing to a certain degree, it cannot comprehensively regulate key

aspects of the housing market.

This means that key areas related to the housing crisis in

Australia remain the responsibility of the states and territories to resolve,

either alone or in collaboration with each other or the Commonwealth.