Issue

Use of restraint of trade (ROT) contract clauses is of

growing interest in Australia. This includes non-compete clauses (NCCs), which

are used in contracts to prevent former

employees working for a competitor or engaging

in work of a similar nature. Of particular interest are the effects

of NCCs on productivity and wages, and options for reform.

Key points

- NCCs

are used to protect business interests like intellectual property.

- Research

suggests NCC use has increased over time in Australia, including among lower

skilled workers.

- The

Productivity Commission (PC) suggests that limiting unreasonable NCC use

would improve productivity and wage growth.

- While

NCCs can promote innovation and investment in workers, their impact on skills

transfer and training remains uncertain.

- Globally,

there are a range of different approaches to regulating NCCs and mitigating

their impacts.

Context

In a capitalist system, open competition between rival firms

fuels progress. This competition allows innovation to flourish and pushes

prices for consumers downward. It also means employees have a choice of alternative

workplaces, improving their bargaining position for salaries and conditions.

At the same time, if a company builds an employee’s productive

capacity through training and skills development, it will likely want a return

on that investment. Historically, employers have used NCCs to protect business

interests such as commercially

sensitive trade secrets, where competitors may access proprietary

information, client lists, product formulas and intellectual

property, pp. 15-16).

Available evidence suggests that NCCs are used by around a

fifth of Australian businesses and apply to around a

fifth of employees, although this is based on limited survey data. The

existence of NCCs can have various ‘chilling’ effects including:

Recent

research suggests NCC use has increased and is a default option in many

employment contracts. In addition to the finance

and insurance sectors and senior roles traditionally covered by NCCs, they

now increasingly apply to ‘outward facing customer roles’ such as childcare

workers, yoga instructors (p. 2), hairdressers

and IT professionals (pp.

19-32). More

broadly, NCCs are ‘no longer confined to highly paid executives but now

apply across income, age, occupational and education groupings’ (p. 1).

What are the arguments against NCCs?

The economic consensus is that NCCs generally do more harm

than good, lowering productivity, wages, and living conditions. Research

also indicates that NCCs can reduce employee mobility, with subsequent

negative impacts on wages and productivity.

Job mobility

While acknowledging inherent methodological challenges, a 2024

study found increased use of NCCs (as opposed to non-disclosure agreements,

or ‘NDAs’, which are an alternative for safeguarding trade secrets) correlated

with decreased job mobility. This was particularly seen in lower-skilled

workers, while impacts across worker age groups were consistent.

Factors other than ROT clauses have also contributed to

lower job mobility in Australia compared with 30 years ago, such as the ageing

of the overall workforce (older workers are less

likely to move between jobs). Regardless, the decrease in job mobility is

notable if looking only at younger cohorts.

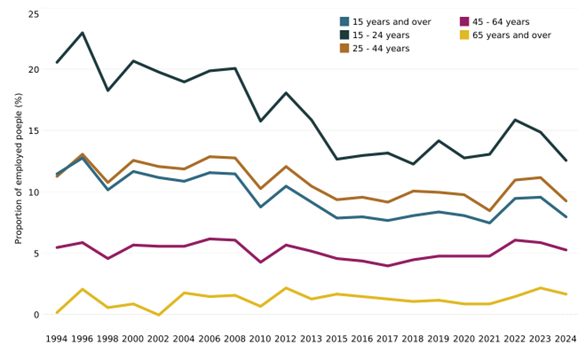

Figure 1 Employed people who changed jobs

during the year by age

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Job

Mobility.

The

COVID-19 period saw a dip in labour mobility for young workers due to lower

demand for less skilled entry-level workers and the negative impact of

shutdowns on industries such as retail and hospitality (where many young

workers are employed). However, this declining trend in mobility started much

earlier (from around 2008) which suggests other reasons may have discouraged

young people from changing jobs. The annual retrenchment rate for all workers

(or rate of job loss due to economic reasons) has fallen

steadily since the early 1990s. As a result, workers are now more likely to

cease jobs voluntarily, mainly for personal reasons, higher wages or better

working conditions.

The 2023 Australian Bureau of Statistics Short

Survey of Employment Conditions noted:

Given the general decline in job

mobility over time, there is an increasing interest in understanding potential

factors that may prevent employees from changing jobs and employers, or that

make it more difficult or less appealing to make a change, or that limit the

ability of employers to attract potential employees to fill vacant jobs. Restraint

clauses are one potential factor. [emphasis added]

Wages

Studies

have shown Australian firms with NCCs paid workers 4% less on average than

comparable firms only using NDAs. While all the workers started with similar

wages, those employed at firms using NCCs experienced slower wages growth over

the first few years of their employment. A further US

study found that states where NCCs were enforceable had 6% lower wages.

However, evidence

on NCCs impact on wage levels is conflicting, with specific caution against

‘confusing correlation with causation’. For example, in the US data has shown

some workers subject to NCCs being better off and earning higher wages. But

this could be due to other factors, such as higher educational attainment.

Contentions that workers subject to NCCs receive more

training is also debated. While some studies supported this view, other

perspectives suggest that firms may need to provide more employee training

given NCCs constrained them from hiring high-skilled workers (pp. 23-24).

Productivity

In 2024 the Productivity Commission (PC) published

modelling into the impacts of the Government’s proposed competition reforms. It

found:

Non-compete clauses constrain job

matching and act as a barrier to labour productivity – therefore, we modelled

this reform as having the direct effect of improving labour productivity, with

the exact magnitude depending on the current prevalence of non-compete clauses

in each industry (p. 24).

The PC’s modelling showed removing all ROTs could increase

Australia’s GDP by up to 0.19%, and the removal of NCCs in industries with

higher use of these clauses could increase wages by 2.4% (Table 1).

Table 1 Summary of labour mobility reforms

| No. |

Short name |

Key direct effects |

Key flow-on effects |

|

L1

|

Restraint of trade clauses

|

Estimated effects:

Increased wages for workers (up to 2.4% in industries with

high use of non-compete clauses and up to 1.4% in others)

|

GDP: +2,569—5,137 m (+0.10—0.19%)

CPI: -0.05—0.10%

Net govt revenue (Cth): +$333—666 m

Net govt revenue (S/T): -$28—55m

|

Source: adapted from PC, National

Competition Policy: modelling proposed reforms Study report (2024): p.

24.

How have other countries regulated NCCs?

Various

jurisdictions have undertaken NCC related regulatory reform (see also OECD

(2023)). Options include:

Australian Government approach

While research on the impacts of NCCs in Australia is in its

early stages, the ABS Short

Survey of Employment Conditions (2023) found 20.8% of 7,000 Australian

businesses used NCCs while a survey

of 3,000 adult respondents using the McKinnon poll by the e61 Institute found

22% were subject to a NCC.

Given this notable impact, the Australian Government has

proposed reforms to NCCs, as part of a broader package of competition reforms.

This includes a

ban on NCCs for workers earning less than the high-income threshold,

currently $175,000

and indexed annually. Following passage of necessary legislation, the reforms

are scheduled to take effect from 2027.

Further reading

- Dan

Andrews and Andrea Garnero, Five

facts on non-compete and related clauses in OECD countries, OECD

Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1833 (OECD Publishing, April

2025).

- Cassie

Boyle, Samantha Saltzman, Jose Francisco Irias and Alison Lewandoski, ‘Non-competes

around the world: Top issues and strategies for global employers’, DLA

Piper GENIE (27 September 2023).

- Treasury,

Non-competes

and other restraints: understanding the impacts on jobs, business and

productivity, Issues Paper (April 2024).

- World

Law Group, Global

Guide to Non-Competition Agreements (The World Law Group Ltd, 2018).