Key issues

- The Australian welfare state is facing significant demographic,

economic and political challenges, which are likely to require a

reconsideration of the structure and funding of Australian welfare programs

to ensure they are meeting their objectives.

- Growing expenditure on universal programs has seen calls for

increased targeting of funding, but governments are also looking to expand

access to support to assist families with cost pressures.

Introduction

The Australian welfare state is facing significant

demographic, economic and political challenges. An ageing population will require

more support from health and aged care services. The need for disability

supports and the cost of services delivered through the National Disability

Insurance Scheme (NDIS) has exceeded

initial projections (pp. 152–153). The Intergenerational

report 2023 found that structural changes in the economy will

narrow the tax base used to fund these services (p. xv). Spending reductions on

social security payments will not offset increases in other areas of social

spending (p. 147). Many developed countries face similar pressures.

These challenges mean that key features of Australia’s

welfare state could be reconsidered – particularly the way that services and

supports are targeted. Growing expenditure on universal systems such as the

NDIS has resulted in calls

for increased targeting, particularly through means testing. However, increasing

the extent of means testing in the Australian welfare state is likely to raise

further complications. Cost of living issues could even see calls for an

expansion in access to government support through universal programs.

Targeting welfare

While there are different academic attempts at classifying the

design of welfare states, Australian academic Peter

Whiteford has suggested there are 3 main approaches:

- contributory – support is distributed based on individuals’ contributions

- universal – benefits are a right of citizenship

- targeted/selective – benefits are provided based on need.

Most countries combine these approaches. For example, in

Australia, income support is targeted to those in need through means testing, mandatory

superannuation has been legislated to provide retirement incomes based on

contributions, and the NDIS and Medicare are universally available to citizens

and permanent residents. Within these broad approaches there may be a further

blending of approaches: the NDIS may be considered ‘universal’ in that there is

no means test, but it is targeted to specific categories of need through

disability eligibility criteria. Whiteford

writes that it is the balance between these 3 approaches that characterises

welfare regimes.

Contributory schemes are often framed as a form of insurance

against risks to an individual’s income such as disability, unemployment and

old age. Targeted schemes are often framed as a means of poverty reduction or a

safety net. Within the insurance frame, income tax and contributions may be

considered as premiums. In the safety net frame, tax revenue is not considered in

direct connection to the welfare programs it funds.

Australia relies much more heavily on means testing than

other developed countries (OECD,

p. 13; Whiteford).

Most other OECD countries have c ontributory social insurance systems alongside

targeted benefits for those who cannot access the contributory schemes. OECD data shows that some countries, such as the Nordic states, make greater use of universal

benefits alongside contributory social insurance.

Targeting in the Australian welfare state

A long history of means testing

Means testing as a way of targeting welfare has been a

feature of the Australia welfare system since the first social security payment,

the Old-Age Pension, was created in 1908. This payment had eligibility

conditions related to age, residency and character, but the decision to include

a means test was contentious. Opponents

to means testing argued that it was a ‘charity dole’ and stigmatised

recipients as paupers, while proponents argued that it should be considered a

retirement allowance earned

through contributions to the community during the recipient’s working life. Cost

was the main reason for not implementing a universal scheme (p. 7). At

the time, the

Constitution limited the federal government’s avenues for raising revenue

(pp. 66–67).

Governments have

subsequently proposed versions of contributory social insurance schemes or

specific tax contributions to fund social services (pp. 8–13). The pension

means test was eased in the period from 1948 to 1976, and was briefly

abolished for those aged over 70. However, this trend has since reversed, with

ongoing concern over growing expenditure on an ageing population (pp. 30–31).

Means testing was applied to other payment categories as the

Australian welfare state expanded. Family payments were initially universal

payments, but have gradually become subject to targeting. Now, all the main

Australian Government payments are subject to means testing – even those

intended to support workers, such as Child Care Subsidy and Parental Leave Pay.

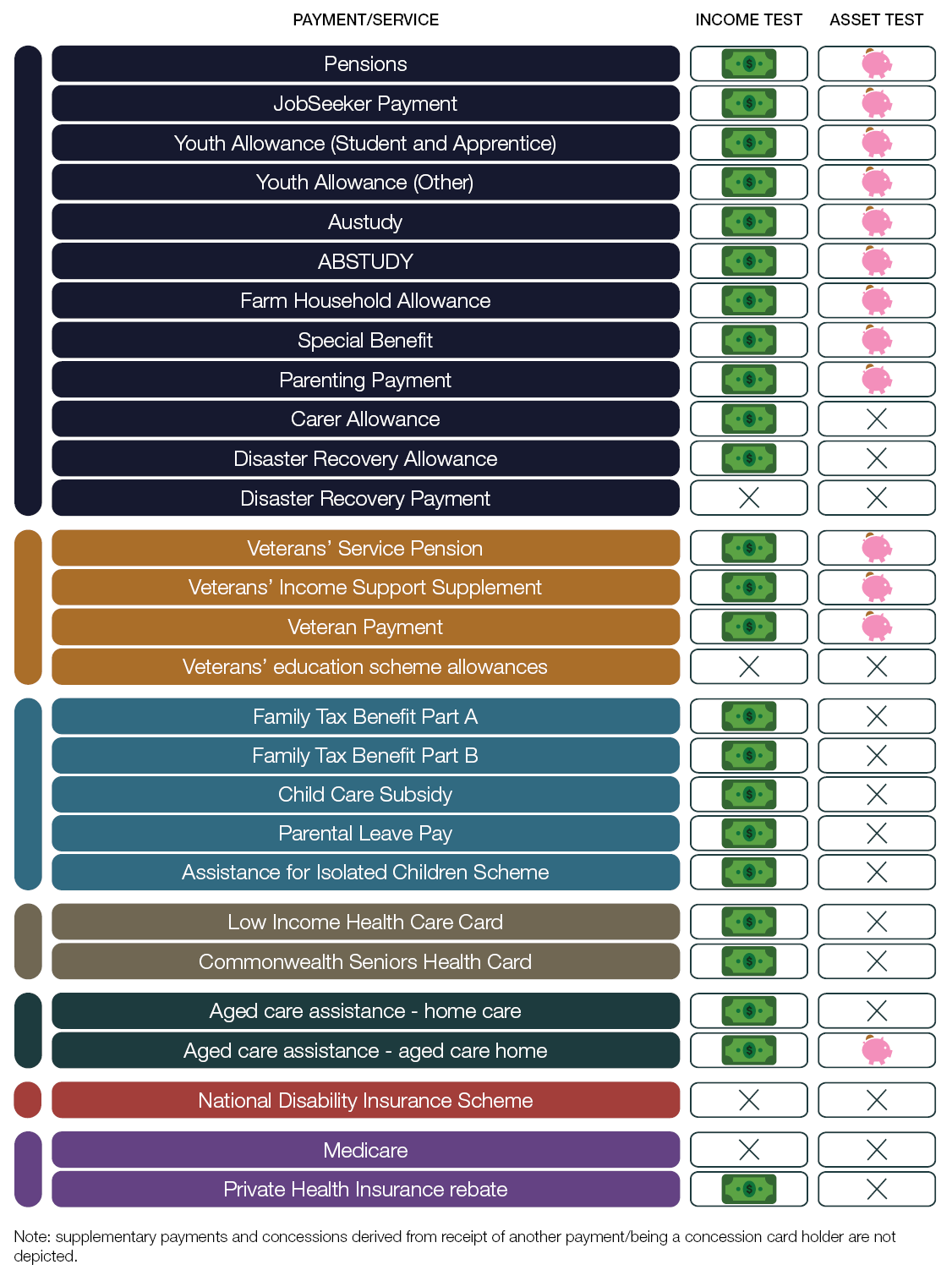

Figure 1 sets out the array of payments and social services

and whether they are targeted through means testing. Each program has a

different means test containing multiple thresholds, taper rates and payment

rates. The ways in which means are assessed can also vary, with different

definitions of income used for social security and family

payments.

Figure 1 Targeting Australian Government social

spending through means tests

Source: Parliamentary Library

Narrowing the target

While the means test for the Age Pension is intended to

target those without adequate means to support themselves, a majority of those

who meet the age criteria (currently 67 years or older) receive the payment. In

2022–23, around 64% of the resident

pension age population received the Age Pension and 71% received some form

of income support (p. 168 and chart

data for Chart 7.20). Around 44% of those above pension age receiving a

government payment received the maximum payment rate. These percentages have remained

fairly steady over the last 30 years. However, Treasury expects that over the

next 40 years, as retirees with higher superannuation balances encounter the means

test, the proportion of this age group receiving a pension will decline to

around 57%, with only 21% of recipients receiving the maximum rate (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Persons of Age Pension eligible age by pension

recipient category

Note: Includes receipt of any government income support pension

including Age Pension, Disability Support Pension, Carer Payment and Service

Pension.

Source: Australian Government, 2023

Intergenerational Report, (Canberra: The Treasury, 2023), 168

and linked chart data for Chart 7.20.

Tightened

means testing has resulted in a reduction of the proportion of children

being supported through family payments. What was once an almost universal

payment – with around 80.5% of children aged under 16 attracting Family Tax

Benefit Part A in 2003–04 – is now paid only to lower income families, with an

estimated 44.7% of children under 16 being supported by the payment in 2021–22

(Figure 3).

Figure 3 Family Tax Benefit Part A children as a

proportion of the population by age group

Note: Unique count of children attracting Family Tax Benefit

Part A in the entitlement year, age at 30 June.

*Data for most years as at quarter 8 (2 years) after

entitlement year to allow for reconciliation, however the year 2021–22 is as at

quarter 6 and is not yet mature. ABS 3101.0 National, state and territory

population, Table 59. Estimated resident population at 30 June each year.

Source: Economic Inclusion Advisory Committee, 2024

Report to Government, (Canberra: Department of Social Services, 2024), 93. Chart data provided by the Department of Social Services.

Recent decisions: funding the NDIS and aged care

There have been various proposals over the last 15 years to

address the growing need for, and cost of, disability and aged care services.

The 2011

Productivity Commission report that guided the establishment of the NDIS

stated that it would be ‘inequitable and inefficient’ to apply a means test – inefficient

because it would exclude high-income people from the most efficient form of

insurance against a severe disability, and inequitable because higher income

people could not access a scheme they had helped fund (p. 262). The commission

argued that ‘the well-off would pay a much larger contribution towards the NDIS

than medium and low income earners’ under its preferred funding model: Australia’s

progressive tax system (p. 262). The commission also argued that means

testing would create disincentives for work and savings.

However, the commission argued that disability care accessed

after Age Pension age should require a means-tested co-contribution, in

the same way as aged care services (p. 17). In this depiction, the

universal disability scheme provides an efficient public insurance model while

the targeted scheme promotes private savings to cover the inevitable care costs

in old age.

The NDIS co-contribution for older participants was never

implemented, but those older than pension age cannot apply for NDIS supports.

Recent

changes to the NDIS aimed at reducing expenditure growth have involved

targeting the range and level of supports offered: by further specifying funded

and excluded services, and changing the structure of participants’ budgets.

The 2021

Aged Care Royal Commission reconsidered the co-contribution model and recommended

establishing an income tax levy to fund universal aged care (pp. 301, 309).

However, the Morrison and Albanese governments decided against the proposed

levy and universal model.

The 2024

Aged Care Taskforce report provided a rationale for not implementing a

specific tax increase to fund aged care:

There are substantial

intergenerational equity issues in asking the working age population, which is

becoming proportionally smaller to pay for these services. Moreover,

superannuation has been designed to support people to grow their wealth and

fund the costs associated with retirement including aged care. (p. 20)

The taskforce supported increasing co-contributions through

a means test to help fund growing aged care costs (p. 20), but did not

consider alternatives, such as changes to tax concessions for superannuation,

so that wealthy older people could indirectly contribute more to funding aged

care.

Current debates – universal child care

In 2023, the Albanese Government tasked

the Productivity Commission with analysing a shift to universal early

childhood education and care ‘in the great tradition of universal Medicare and

universal superannuation’ (p. v).

The commission’s

final report presented a universal system as one where all children have access to high-quality services (p. 4). The proposed system retained a

means-tested subsidy with higher levels of support to low-income families,

removed activity-testing and contained measures to improve the supply of child

care places (pp. 5–7). The commission found non-means tested options would

involve greater increases in government expenditure, with most of the benefits

and increased demand for child care going to higher income families (pp. 33–34).

However, the non-means tested options would see a stronger (though small) increase

in labour market activity from parents, compared to its preferred option (p. 37).

International responses to pressure on welfare

systems

Contributory pension schemes in Europe, which rely on the

contributions of current workers to fund the pensions of retirees, are

under increased financial pressure due to smaller ratios of workers to

retirees. Most

OECD countries have increased pension ages and shifted occupational pension

schemes from defined benefit to defined contribution models (pp. 42–45; 47).

The UK’s welfare system, which combines contributory,

means-tested and universal elements, has seen the gradual

decline of contributory benefits. Contributory payments to working-age

people have declined from around a third of welfare benefits (including tax

credits) in the late 1970s to around 8% in 2019–20. Benefits for retirees were

following the same trend, but policy changes in the 2000s and 2010s have

restored the basic state pension as a flat-rate, non-means tested payment for

most retirees, which can be topped up with means-tested additional support or

private savings.

Other countries are implementing universal programs. In

2021, the Canadian

Government announced a plan for a universal child care system with average

out-of-pocket costs at $10 per day and 250,000

new places by 2026. Some academics

have questioned whether the goal can be achieved and whether there will be

enough additional places to meet increased demand.

How social spending compares

Australia’s use of targeting has kept its public

social spending, including on health, close to the OECD average – at 20.5%

of GDP in 2019 (the most recent comparable data). However, when private social

spending (such as superannuation contributions) and a variety of tax

concessions are included – what the OECD describes as ‘net social spending’ – Australia

is one of the biggest social spenders at 24.9% of GDP (ranked sixth) (Figure 4).

These tax

concessions often benefit higher income earners (because they have higher

tax liabilities) and low-income workers often miss out on private social

benefits.

Figure 4 Public and net total social expenditure,

% of GDP 2019

Notes: ‘Gross public expenditure’ refers to total direct public

spending on benefits and services. ‘Net total social expenditure’ includes social

benefits delivered through the private sector such as superannuation, and tax

expenditures which deliver social supports such as tax credits for dependent

children. The numbers in brackets refer to country rankings in terms of gross

public and net total social expenditure, with number one being the highest

spender. For example, the US ranks 23rd in the OECD in term of gross public

social expenditure and second in terms of net total social expenditure.

Source: OECD

Social Expenditure database 2023

Future directions

Countries around the world are responding to economic,

demographic and environmental challenges to their welfare states in a variety

of ways – through greater targeting, through universalism, and through hybrid

approaches.

In Australia’s case, some commentators and international

bodies have argued that budget pressures create the need for more private

spending and means testing of social supports (p. 31). While this can

improve the government’s fiscal balance, it shifts costs onto individuals and

families and will see some miss out on the support they need.

Expanding social spending and creating more universal

supports would require more tax revenue or government debt. Universal systems provide

broader coverage against risks to wellbeing and income, are simpler to navigate

and administer, and remove the stigma attached to means-tested welfare.

However, universal systems have finite resources – supports may be rationed

(through waiting lists or eligibility criteria) and broader coverage can limit

the level of support provided. Additional support to high-need groups is often

necessary.

In meeting the challenges, policymakers will need to consider:

- What are the social objectives of welfare policy – an investment

in the wellbeing of Australians; insurance against risks to income and

wellbeing; reducing poverty or inequality; as a safety net of last resort; or a

combination of these?

- How should resources be redistributed to fund welfare policies – from

the rich to the poor; across generations; from workers to those unable to work?

- What are the most effective and efficient mechanisms for

achieving the objectives and redistributing resources?

Further reading

- Don Arthur, Myths

of Entitlement: A History of the Age Pension and the National Welfare Fund,

Research paper series, 2021–22, (Canberra: Parliamentary Library, 2021).

- Ben Spies-Butcher, Politics,

Inequality and the Australian Welfare State after Liberalisation (London:

Anthem Press, 2023).

- Dimitri Gugushvili and Tijs Laenen, ‘Two Decades after Korpi and Palme’s “Paradox of Redistribution”:

What Have We Learned So Far and Where Do We Take it From Here?’, Journal of International and Comparative Social Policy 37, no. 2 (July 2021): 112–127.