Papers on Parliament No. 61

May 2014

Michael Tate "Andrew Inglis Clark, Moby Dick and the Australian Constitution"

Prev | Contents | Next

In 1865, in my home city of Hobart, a young

apprentice of 17 raced through his father’s workshop, a foundry and sawmill,

yelling out that Robert E. Lee had surrendered, signalling the end of the Civil

War in the United States of America.

In 1891, the Attorney-General of the colony of

Tasmania submitted a draft federal constitution to the Convention meeting

outside Sydney.

The Attorney-General had been that 17-year-old

boy. As a teenager, Andrew Inglis Clark heard tales of the Civil War from the

whalers out of Nantucket, Massachusetts, who took shelter in the Derwent River

from the Confederate Shenandoah which was preying on the fleet of Union

whaleships as it followed whales in the Southern Ocean.[1]

Of course, Nantucket was the port out of which

Henry Melville has Captain Ahab setting out in pursuit of Moby Dick, the great

whale which had bitten off his leg.

This is my somewhat feeble justification for the

title of these opening remarks. When I saw the titles of the presentations to

be delivered today (some with a hint of revisionism!), I thought I had to be

just as ingenious.

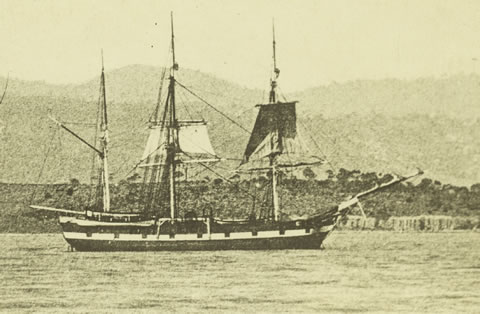

The title also gives me the opportunity to show

a picture of one of those whalers, later named the Derwent Hunter. There

is a nice connection with an item in the display case in the foyer. It is a

reproduction of an original water colour of Inglis Clark being rowed out to

join the drafting committee on the Lucinda in Sydney Harbour on Easter

Day 1891.

Derwent Hunter on Derwent River, c. 1880. Image courtesy of W.L. Crowther Library, Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office, AUTAS001126070309

One might say that the Australian Constitution

was both water-born (in 1865) and water-borne (in 1891).

Inglis Clark was fascinated by the United States

of America. As a young lawyer, he presided at a dinner celebrating the

Declaration of Independence (1876), visited his idol Oliver Wendell Holmes in

Boston (and named one of his sons after him), and became totally entranced by

the US Constitution.

Despite the very

different geneses of the US and Australian federations, the one forged in

revolution and bloody warfare, the other sluggishly evolving with no great wave

of popular enthusiasm, it was in the mind of this not very prepossessing

Tasmanian lawyer that the US Constitution provided a working model adaptable

into the colonial tradition of responsible government.

I am not going to

teach grandmothers to suck eggs. This audience knows far more than I do of the

exploits of Andrew Inglis Clark. But I am sure that individually each one of us

will learn something new and for that possibility we are indebted to Dr

Rosemary Laing, Clerk of the Senate, and Dr David Headon, History and Heritage

Adviser for the Centenary of Canberra.

Rosemary and David

must have a sixth sense, refined by their years in Canberra. In a moment of

prophetic inspiration, they chose the Friday before the convening of the 44th

Parliament to host this symposium. This 44th Parliament owes so much of its

structure to the genius of Andrew Inglis Clark.

They are of such

stature that an eminent group of speakers and panellists has responded to their

invitation to focus on a sometimes obscured progenitor of the Constitution of

the Commonwealth of Australia.

It is probably

fair to say that most Australians are only vaguely aware of our Constitution,

though the Australian Electoral Commission is doing its best to stimulate some

interest in it![2]

I felt this

neglect very acutely yesterday when I visited ‘Constitution Place’ at the

eastern end of the Old Parliament House. It is a rather sad little plot. Perhaps

we might hope that this symposium may be a catalyst for doing something more to

embellish that area with some tribute to the founders of our Constitution.

There must be some happy medium between the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia and

the rather pathetic little plaque at Constitution Place.

Inglis Clark was a

man with a touch of the obsessive, one part focused on the US, the other on

matters of religion.

He had forsaken

his Baptist allegiance, I think in his early twenties, and became a Unitarian

‘freethinker’ very opposed to any favouring of any denomination of the

Christian religion.

Inglis Clark’s

draft Constitution reflected his Tasmanian battle against state aid to Catholic

schools. It proposed to forbid the Commonwealth Parliament’s making of any law

‘for the establishment or support of any religion ...’ (emphasis added).

I need not go

through the purely pragmatic political manoeuvring which ended up with section

116 constraining the Commonwealth Parliament, rhetorically balanced by the

clause appearing in the Preamble: ‘... humbly relying on the blessing of Almighty

God’.

As is well known,

that clause was put in to secure the support of (male) churchgoers for the

referendum needed to adopt the Constitution.

Talking of

referenda, section 116 does not apply to the states. (Only Tasmania has a

similar provision in its constitutional structure, but by way of an ordinary,

repealable provision in an Act of Parliament.)

What could be more

fitting as a tribute to Andrew Inglis Clark than to extend section 116’s entrenched

constraint so as to limit the capacity of the states in this regard?

In 1988, the then Attorney-General of the

Commonwealth promoted a referendum to do just that.

It fell to me as Minister for Justice, sitting

in the Senate, to get the bill authorising the referendum through that august

chamber. It was a gruelling process but this question was eventually put to the

people. Yea or nay to:

116. The Commonwealth, a State or Territory,

shall not establish any religion, impose any religious observance, or prohibit

the free exercise of any religion, and no religious test shall be required as a

qualification for any office or public trust under the Commonwealth, a State or

Territory.

Never has a referendum been so comprehensively

and decisively rejected!

Only 30 per cent of voters Australia-wide

favoured the amendment and there was no majority in any state.

So, as a boy from the port city of Hobart, I

enjoyed much less success (let’s face it, no success) compared with the

influence of the subject of this conference on the shape and provisions of the

Australian Constitution.

Whales have long departed the Derwent River. Was

this an omen?

The success and singular contribution of Andrew

Inglis Clark was made possible by his friendship with the whalers out of Nantucket.

In opening this conference I give you—Andrew Inglis Clark, Moby Dick and the

Australian Constitution.

[1] I am indebted to a wonderful article by John Reynolds

for this story: ‘A.I. Clark’s American sympathies and his influence on

Australian federation’, Australian Law Journal, vol.

32, July 1958, p. 62.

[2] This was a reference to the Australian Electoral

Commission’s loss of ballot papers marked by voters in the 2013 Senate election

in Western Australia.

Prev | Contents | Next