Papers on Parliament No. 61

May 2014

James Warden "Andrew Inglis Clark Deserves to Be Remembered Across the Great Divide"

Prev | Contents | Next

The centenary of the United States was a

surprisingly significant event in Tasmania in 1876. This paper traces the

connections that developed between the United States of America and Tasmania as

the context for Andrew Inglis Clark’s developing ideas about civil and

political society and his understanding of the comparative historical

experiences of the two places. The paper is concerned with the context in which

ideas and materials were transferred around the globe in politics, culture,

literature, theology, science, technology, metaphor and spectacle.

Across the great divide

Clark died on the morning of Thursday 14

November 1907 at his residence ‘Rosebank’ in Battery Point, Hobart. He was 59

years of age. Two days after his death an obituary appeared in The Mercury under the pen name ‘Jacques’ who remarked with

tenderness on the exit of a friend:

A spotless private life was the crown of a

useful public one, and the name of Andrew Inglis Clark deserves to be

remembered across the great divide with a tenderness and regard which few other

public men have been able to so justly claim at the hands of their fellow

countrymen.

Jacques indicated not only the length of his own

association with Clark and Tasmanian politics but more importantly gave clues

to the early formation of Clark’s political ideas[1]:

My earliest recollections of Andrew Inglis

Clark take my thoughts back to the early seventies when he used to preside at

the American dinner which was held annually, on July 4, at Beaurepaire’s.

The obituary note in The

Mercury provides evidence for the early origins of Clark’s enthusiasm

for the United States and the political and philosophical inspirations that

were to cascade through his life and into the design he proposed for the

Australian Constitution. This encompasses his influence in the early Australian

federation meetings, the First Convention in Sydney in 1891 and the importance

of his draft model for an Australian constitution when, amongst other thing

things, he deflected the Canadian constitutional version of the division of

powers in favour of that of the United States.[2] Crucially,

Clark’s American ideas were not restricted to constitutional drafting or

questions of judicial review. The republic that Clark saw before him

represented a great human achievement and imposingly stood in comparison with

his own home and place of birth, Van Diemen’s Land. This paper explores some of

those associations that inspired Clark in the 1870s.

Clark’s American dinners

Beaurepaire’s was the eponymous nickname of the

Telegraph Hotel in Morrison Street on the Franklin Wharf. So, what were the

American dinners at Beaurepaire’s all about? Indeed that question is the

departure point for this paper. Larger questions are then entailed about how

ideas travel across the great intellectual and political divides and across the

world. To rephrase the question: How did Clark in Hobart by the early 1870s,

aged in his mid-twenties, make the transition from received mid-century British

ideas to Reconstruction era American republicanism?

Clark was born in 1848 to a sound and

respectable family. He lived in Collins Street Hobart. He was home educated

then attended a local private school. Prior to entering the legal profession he

had engineering training with facts, measurements and mechanics. Locally and

circumstantially he also ingested the rule of law, the utilitarianism of Jeremy

Bentham and John Stuart Mill, responsible viceregal government with a

restricted franchise, the anti-transportation movement, Chartism and the

various denominations of English and Scottish churches that surrounded him in

everyday life. He also lived in a place steeped in civic shame in the

half-light of the convict shadow over Tasmania and with the continuing shame,

felt even at that time, in the spectre of Truganini and her people. Around him

in the streets of Hobart were former convicts and their keepers. Every day of

his life the young Clark passed amongst the broken bodies and lost souls of

those who had outlasted but never really escaped the system. For good measure,

Andrew Inglis Clark’s father Alexander Clark was the engineer who had built the

treadmill and granary at Port Arthur in 1843–44, the building that later became

the Benthamite model prison.

Such questions of historical context that arise

for Clark may be elevated even further, to sharpen them, to make them more

acute: How did Clark, the local Tasmanian boy, come to adopt American pluralist

democracy, the ideals of republicanism, natural rights theory, proto-feminism,

the case for a written federal constitution as well as the New England version

of Unitarianism and the Transcendentalists? In other words, in a rhetorical

turn, how did Clark get from Van Diemen’s Land to Massachusetts, from Collins

Street to Concord, from Hampton Road to Harvard and from Battery Point to

Boston and back? How did he get across that great divide? Manchester, if

anywhere, might have been a more obvious philosophical cradle for a young

independent-thinking Tasmanian. Becoming a freethinking natural-rights

republican is a prodigious intellectual leap. In this context the American

dinners are of real interest. It may be surmised that he must have read Thomas

Jefferson to find his way to Beaurepaire’s on that evening in July 1876. That

evening he ideationally went to Morrison Street via Monticello. For a short

walk it was quite an intellectual journey.

Louis Isidore Beaurepaire, a Frenchman, was a

professional chef who left the service of Governor Frederick Weld in 1875. In

advertising his new establishment, Monsieur Beaurepaire styled himself as

previously the chef-de-cuisine for Sir George Bowen and Sir James

Fergusson.[3] This may have been during their time in New Zealand where

they had successively been Governor.[4] Weld and

Fergusson were friends and Weld had visited Fergusson in New Zealand just

before he (Weld) took up the Tasmanian position. So, Beaurepaire joined Weld’s

service from Governor Fergusson either directly from New Zealand or from his

previous position in South Australia. However, Louis Beaurepaire did not stay

long in the service of Governor Weld, for within a just a few months he had

taken the licence of the Telegraph Hotel on the Hobart wharf. Previously the

hotel had been called the Electric Telegraph Hotel, to distinguish the earlier

usage when telegraph meant what we now call the semaphore. In Hobart the

semaphore had been associated with signalling from Port Arthur but the electric

telegraph was modern and when it joined Hobart and Launceston in 1857 it was

surely a signal that the convict days may be left behind. In 1875, as a symbol

of social progress, politeness and good taste, Beaurepaire’s had quickly become

the best establishment in the colony.

Telegraph Hotel photographed by the Anson Bros, c. 1887. Image courtesy of Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office, AUTAS001125642355

Louis Beaurepaire’s licence to the Telegraph

Hotel was granted in late 1875 and renewed on 2 December 1876. From late 1875

Monsieur Beaurepaire was already catering for Tasmanian society at various

events including viceregal functions, race day luncheon at Elwick, the

prestigious Poultry Association dinners, visiting cricket teams and the Hobart

Regatta.[5] If there had been Michelin stars then Beaurepaire’s would have had

them. But, misfortune seems to have befallen the Beaurepaire family, for on 1

October 1877 a notice of public auction appeared in The

Mercury for all the goods and chattels of the Telegraph Hotel. By then

the hotel was being operated by a woman by the name of Harriet Clark (no

relation) followed by a succession of other licensees. The standards of the

hotel appear to have markedly declined. So, although the American Club in

Hobart was seemingly born on the fourth of July 1873, the number of celebration

dinners of the American Club at Beaurepaire’s could have been only two at most.[6]

The first possible 4 July dinner at Beaurepaire’s

was 1876 and the second in 1877.

Portrait of Marcus Andrew Hislop Clarke photographed by Batchelder & Co. Image courtesy of State Library of Victoria, H29322, image a15338

So, let us get to the 1876 dinner. The meeting

on 4 July 1876 in the dining room of the Telegraph Hotel was convened by the

28-year-old President Andrew Inglis Clark with other ‘young, ardent

republicans’.[7] There could not have been many of them. When rendered into English beaurepaire means beautiful retreat. For ‘ardent young

republicans’, especially in Tasmania at that time, their endeavour ought to be

seen as an audacious advance.[8] Clark said in his speech that evening:

We have met to-night in the name of the

principles which were proclaimed by the founders of the Anglo-American Republic

... and we do so because we believe those principles to be permanently applicable

to the politics of the world.[9]

The cadence of this sentence may have a little

bit of Lincoln to it. ‘We have met here to-night ... ’, said Clark. ‘We are met

on a great battlefield ... ’, said Lincoln, and so forth. But this would be an

exaggeration because by present standards Clark regrettably is not a

particularly engaging writer. He is long-winded and often laborious. His

language generally lacks rhythm and it is too ornate. His meaning wilts in

imprecision. Perhaps that style made him a good Judge of the period. While

Clark read Lincoln deeply he did not have an ear for Lincoln’s lean, rich

language. If the American historian Garry Wills is right that the Gettysburg

Address profoundly changed political language then unfortunately Clark did not

grasp that point.[10] Clark writes as a high Victorian rather than as a new republican of

the reconstruction era. Wills argues that Lincoln of the later period wrote

with spare elegant phrasing because he had spent the Civil War in the Telegraph

Office of the White House. He was the first telegraph President. Alas President

Clark in the Telegraph Hotel lacked that style. Clark wrote long letters. He

should perhaps have written more telegrams or at least have applied more

consistently that economy to his drafting style and to his own prose.

Despite the three earlier meetings of the

American Club, the date 4 July 1876 is the moment when Clark’s political

interests solidified into permanent principles—as Lincoln would have

it—dedicated to the proposition that ‘all men are created equal’. Lincoln got

the phrase of course from Jefferson in the Declaration of Independence,

for whom men are endowed with ‘unalienable rights’. The point here is that

Clark in 1876 in Tasmania adopted and expressed those audacious self-evident

ideas. He may also have adopted Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s proposition that ‘man

is born free’ which Jefferson in the shadow of slavery of course could not say.

Clark, via John Stuart Mill, also seemingly grasped Mary Astell’s fundamental

question about women. Astell, writing in 1700, anticipated Rousseau with the

question that if men are free why are women ‘born to be their slaves’ to be ‘now

and then ruin’d for their Entertainment’?[11]

The language of freedom in Tasmania

Such high-flown language is almost entirely

absent from Tasmanian political prose. Yet somehow Van Diemen’s Land, born in

chains in 1803, turned into the Tasmania of 1903 with the universal franchise.

The magnitude of that change ought to be emphasised and more fully appreciated.

No polity in the history of the world has had such transformation. In 1808, on

the Hobart town parade ground, a woman called Martha Hudson was brutalised on

the arbitrary orders of Lieutenant Edward Lord. For insubordination, she was

tied to a moving cart, stripped to the waist and publicly flogged to

unconsciousness.[12] In 1914 three women living in Tasmania also by the name of Martha

Hudson are shown on the electoral rolls.[13] By 1903 in

Tasmania the powers of government can be seen to arise from the consent of the

governed. The transformation occurred almost wholly within the span of Clark’s

own short lifetime. Liberal democracy, whatever its shortcomings, was achieved

in Tasmania without poetry, statuary, arches, marches, bronze busts, stone

monuments or even an annual day of celebration. That extraordinary

transformation goes still unnoticed and remains to this day pitifully

unremarked. Yet all of the republican ideas of consent, constitutions and

freedom that are associated with liberal democracy were at play in the

formalities of the dinner that cold Hobart evening in 1876 in the dining room

of Beaurepaire’s as Andrew Inglis Clark’s proposed the toast to the Declaration

of Independence. His speech that night can stand as the moment that brought

forth, for him at least, the idea of a new republican nation.

The republic here is not just a narrow

constitutional question of the Crown and the viceregal office. Clark held the

wider idea that Tasmania needed a new birth of freedom. The faces in the

streets of Hobart in 1876 would have told him so, for Clark natively understood

the tyranny portrayed in Marcus Clarke’s His Natural Life, published as

a serial between March 1870 and June 1872. The first edition of the book in

1874 was called For the Term of His Natural Life. It has never been out

of print. Moreover, Port Arthur did not finally close until 1878. Even if Van

Diemen’s Land was somewhat luridly presented in Marcus Clarke’s literature, the

penal system nonetheless achieved its mundane objective of grinding rogues down

(if not ‘honest’ as Jeremy Bentham prescribed).[14]

Social contract theory, the bearer of the

political concept of consent, had been so diluted as to be absent under the

Crown in Van Diemen’s Land. At best it was Thomas Hobbes’ grim version of the

social contract, not the more liberal versions of Grotius, Locke or Rousseau. Natural

Life in Van Diemen’s Land was designed and intended to be solitary, poor,

nasty, brutish and long. The sentence that precedes the famous quotation from Leviathan

is worth revisiting. The state of nature is a place for Hobbes with:

no knowledge of the face of the earth, no

account of time, no arts, no letters, no society and which is worst of all,

continuall feare, and danger of violent death. And the life of man, solitary,

poore, nasty, brutish and short.[15]

The central contradiction of the convict system

in Van Diemen’s Land was to maintain the solitary, nasty, brutish system whilst

simultaneously willing society, arts, letters and science to emerge over time.

Moreover, maintaining brutality and developing productive economic labour were

also fundamentally at odds.

On natural life

For a while—take the year 1822—two jurisdictions

exemplified how the state of nature was internalised into captive institutions:

Van Diemen’s Land for convictism and Virginia for slavery. Both places, for

some pitiful people, simultaneously allowed both the iron manacles of the

Leviathan state and the ever-present menace of the state of nature. Even Hobbes

himself did not apparently contemplate that miserable co-existence. Leaving

slavery aside, natural life in criminal law was a term denoting penal

detention of no definite period. The phrase was originally informed by

protestant theology wherein natural life also meant the base existence

of the corrupted flesh. This idea or origin of natural life appears to lie in

the theological distinction between natural life and spiritual life. Two

examples from evangelical literature will suffice. For example, the relationship

between natural life and spiritual life was described in a sermon by the

nonconformist clergyman Phillip Henry (1631–1696) who had suffered in the

‘Great Ejection’ from the newly established church under the Act of Uniformity

of 1662. His sermons were finally published in 1833 with those of his son,

Matthew Henry (1662–1714) who was a strenuous and influential Presbyterian

sermoniser and commentator on the Bible. For Phillip Henry, ‘Life is

three-fold; there is natural life, spiritual life and eternal life’. The life

of the body flowed from its union with the soul, when body and soul part, we

die. Spiritual life is the life of the soul flowing from its union with God;

when God and the soul come together the soul lives, when they part it dies.

Only Jesus can bring soul and God together. Without the union of body and soul

the natural life of the body is already in immanent death. The third stage

after natural life and spiritual life is eternal life, which is life in heaven.[16]

The second example is from the implacable Edward

Irving (1792–1834) of the Church of Scotland who was obsessed with biblical

prophecy and the book of Revelation. For him the natural life was deemed to be

dead and wicked, as in the embodiment of the fallen Adam in a devil-possessed world.

For Irving:

This is the true idea of original sin: That

man like God hates all natural life, and loves to make it die because it once,

and but once, sinned against God.[17]

Natural life in this

context is an unredeemed pitiless state of sin, stain and immanent death in

contrast to the spiritual life, when one is joined to God through Jesus Christ

allowing the entry into eternal life, everlasting. Natural life, in this form,

is a living death of venality, spiritual abandonment and terminal

incarceration. Natural life here is dramatically embodied in the doomed figures

of—say—the cannibal Alexander Pearce and the benighted abused Rufus Dawes. Or,

as Sir Francis Forbes in evidence to the Molesworth Committee of the British

Parliament in 1837 said of convict transportation, ‘in my opinion ... may be made

more terrible than death’.[18]

That quotation is given as the frontispiece to the first edition of For the

Term of His Natural Life. That proposition is oddly the general reason too why

John Stuart Mill in 1868 was able to justify the utility of capital punishment.

Mill argued that natural life in incarceration may be worse than death.

Execution was justifiable on utilitarian grounds.

That is one version

of natural life—the miserable Van Diemen’s Land version. However, on the other

side of the great divide, the idea of natural life is embodied by Henry David

Thoreau who deeply yearned for a natural life of organic individual freedom.

The sort that might ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire to the

snow-capped mountains of the Rockies.[19] Thoreau’s

natural life was to be realised at Walden. But he used the phrase natural life

in 1849 in the final chapter of his book A Week on the

Concord and Merrimack Rivers.[20] ‘A natural

life’, wrote Thoreau ‘round which the vine clings, and which the elm willingly

shadows’. Such a life ‘needs not only to be spiritualized, but naturalized, on

the soil of earth’. This happy expression of natural life as a shelter would

soon be Walden: A Life in the Woods (1854).[21]

So a natural life in Van Diemen’s Land and a

natural life in Massachusetts were not the same. In linguistics, in technical

language, this is called an auto-antonym or a contranym; words or phrases with

the same spelling but with diametrically opposite meanings. Apt examples are

the words sanction—to permit or to punish—and the word bolt—to

hold fast or to go free. Thus there is an auto-antonym inherent to the term

‘convict bolters’, escaping the bolts to go free, and if the bolters were lucky

they would get to China. Surely a defining theme of the history of Tasmania

from convictism to the present has been the ambition to cross over from the

misery of Alexander Pearce’s natural life pining on the Gordon River to

Thoreau’s version of the natural life to let the Gordon and Franklin wild

rivers run free and the people to run free with them. From the Concord and

Merrimack to the Franklin and Gordon and Derwent and Tamar rivers, this is an

emotional social and political Tasmanian dream of freedom and Andrew Inglis

Clark himself had that dream or vision of civic, political and psychological

freedom. He hoped for Tasmanians to cross that great divide of the convict

sanction of natural life to a deliberate examined natural life, born in the

larger idea of republicanism. He was reaching for a new world of freedom and

independence—to domesticate to Tasmania that version of a civic religion. The

birth of that idea for Clark may be tendentiously placed, or perhaps just

symbolically placed, in his presidential speech at Beaurepaire’s in 1876. For

three decades, to come, he pursued that ideal derived from American liberation

philosophy as he tried, without hyperbole, to apply it in Tasmania.

And so to Philadelphia

The immediate reason for the toast by Clark that

night in 1876, and the reason everyone else was interested in the United States

at that time, was the centenary of the Declaration of

Independence for which there is a substantial material Tasmanian

connection. The central event of the centenary was the Philadelphia

International Exhibition, styled as the first World’s Fair.[22] It ran from 10 May to 10 November 1876. The date 10 May was

chosen as the opening day as that day was the seventh anniversary of the

completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869 when the eastern and western

rail lines were tied with silver and golden spikes at Promontory Summit, Utah,

below the snow-capped mountains of the Rockies. The Central Pacific and the

Union Pacific lines were joined. After the Civil War this was the single most

important event that made the nation. The railroad surveys of the continental

watershed in the Rocky Mountains in the mid-1860s also delivered the phrase

‘across the great divide’, according to Webster’s Dictionary.

Ten million people attended the Philadelphia Exhibition in 1876, one fifth of

the American population. It had 200 buildings. The main building was the

largest in the world, temporarily. Richard Wagner, deeply indebted, wrote the

music for the Centennial March. He reputedly said ‘the only good thing about

that piece of music was the fee’ which was $5,000 and paid in advance.[23] The grand march was played on the morning of 10 May by an orchestra

of 150 musicians with a chorus of 800 voices before an audience of 25,000.

Reviews were mixed.

The centennial event had been planned since

1868. In the wake of the Civil War it was a supra-national reconstruction

project. Accordingly, the Fair was interpreted in the context of the founding

principles of the Union, just as Lincoln had done for the Constitution itself

at Gettysburg in 1863, four score and seven years after 1776. Philadelphia was

a huge ideological and technological international event. Earlier exhibitions

in London, Paris and Vienna had been studied and copied. Eleven nations had

their own buildings, as did twenty-six of the 37 US states. Philadelphia showed

the first typewriter (Remington), the first galvanised steel cables for the

Brooklyn Bridge, Heinz Ketchup from Pittsburgh, penny farthing bicycles,

Wallace–Farmer dynamos that made electric light and the right arm and torch of

the Statue of Liberty. The exhibition showed the first telephone by Alexander

Graham Bell that he had developed in attempting to improve Samuel Morse’s

telegraph. In just two years, by 1878, Bell Telephone would already rival the

telegraph. Also on display were the objects and results from the extensive

global scientific exercise by the United States Navy to plot the 1874 incidence

of the Transit of Venus, just over one hundred years since Captain Cook had

undertaken the same task.

Crew of the USS Swatara on deck, 1874. Image courtesy of Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office, PH30/1/112

So, how does Philadelphia relate to Tasmania?

The answer is found as a direct consequence of the visit to Hobart by the

United States Navy from October 1874 to February 1875 on the Transit of Venus

expedition. The USS Swatara visited for the purposes

of that scientific endeavour and left behind in Tasmania great public

enthusiasm for the United States of America.[24] (Much more

so than the visit of the USS Enterprise would achieve

in 1976.) The Commander, Commodore Ralph Chandler, became a celebrity in

Tasmania along with William Harkness who led the scientific party. On the

evening of Tuesday 24 November 1874, Captain Chandler was seated beside

Governor Charles Du Cane at the Governor’s substantial farewell ball in Hobart.

It was a ‘brilliant assemblage in the Town Hall’. Moreover, wrote The Mercury, ‘we have had nothing equal to it in Tasmania

for a long time’. It was deemed as big as or bigger than the Duke of

Edinburgh’s visit. The British flag hung on one side of the large room and the

American flag on the other in honour of the presence of the Swatara

and thanks to Captain Chandler the committee had been able to display flags of

all nationalities.[25] All things American were embraced.[26] The

Governor regretted that the breakup of his household prior to his departure did

not permit the sufficient extension of hospitality to ‘our gallant visitors

from the other side of the Atlantic. (Loud Applause)’.[27] Note, that

the Governor did not say ‘the other side of the Pacific’. He said, ‘the other

side of the Atlantic’, which neatly locates both Tasmania and its departing

Governor sentimentally within the bosom of Mother England. Had Andrew Inglis

Clark been at the gala dinner that evening he would surely have had a different

perspective. Neither the Clark nor the Ross families appear to have attended.

Perhaps they were not sufficiently socially well recognised as to be invited.[28] But, according to the Australian Dictionary of Biography

entry on Charles Du Cane, Truganini attended the Governor’s last levee. Four

days later he departed for England. The transit of Venus occurred on

9 December 1874. A month later, on 13 January 1875, Governor Weld assumed

office and his household retinue had a new chef-du-cuisine.

During early 1875 the Tasmanian Government of

the progressive Premier Alfred Kennerley was heavily pressured by the Victorian

Government and the Tasmanian newspapers to participate in the Philadelphia

Exhibition. Melbourne was driving the Australian campaign led by Sir Redmond

Barry. In preparation for Philadelphia the Victorians initiated a Melbourne

intercolonial exhibition in late 1875 to funnel and filter the Australian

exhibits.[29] By April 1875 the Tasmanian Government agreed to participate and

established a Royal Commission for both the Philadelphia and the Melbourne

intercolonial exhibitions, with Sir James Wilson MLC as the chair supported by

about twenty commissioners, north and south. It was a significant

organisational and financial commitment.

Philadelphia was a colossal event and a very

substantial Tasmanian effort was made.[30] Tasmanian businesses and individuals provided minerals, native seeds

and timbers, fleeces and skins, agricultural produce, manufactures, artworks

and handicrafts. Lengthy essays emphasising the pride of Tasmania were written

that allowed only the slightest mention of a convict past. Much statistical

information was included. When the time came the Australian colonies sent

commissioners to Philadelphia to curate their exhibitions. The Tasmanian stall

was at the rear of the large New South Wales stall. The main day in

Philadelphia was of course 4 July 1876. The Declaration of Independence,

the original document itself, was unveiled, on loan to the city with special

permission from President Ulysses S. Grant. Richard Henry Lee’s grandson (of

the same name) read the Declaration aloud because in 1776 his grandfather had

proposed the Resolution of Independence from which Jefferson’s Declaration

followed two days later.

On that same day in Tasmania, 4 July, the Launceston

Examiner published the entire text of the Declaration of Independence.

That night in Hobart, President Clark’s American dinner took place at

Beaurepaire’s Telegraph Hotel. Whilst in Melbourne the celebration took place

at the home of the American vice-consul S.P. Lord, ‘Manhattan’, in Carlisle

Street, St Kilda. Toasts were drunk to President Grant, Queen Victoria and the

Governor of Victoria, who was none other than Sir George Bowen who by this time

had transferred from New Zealand. By invitation of Mr Lord the Declaration

of Independence was read ‘with good elocutionary effect’ by the Reverend

Charles Clark. A toast to the Declaration was proposed with musical honours

moved by Mr Lord.[31]

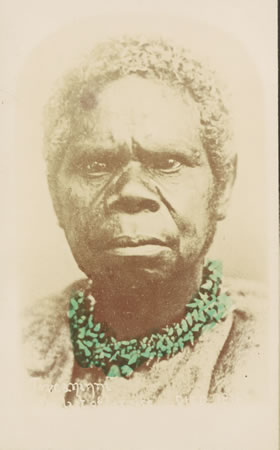

At the close of the Philadelphia Exhibition the

official review had this to say about Tasmania:

From Tasmania there was much to interest,

(sic) prominent among the exhibits being some curious photographs of aboriginal

women, one of them being the sole survivor of the Tasmanian aborigines. There

was also a companion portrait of ‘Billy Lanney’, the last Tasmanian aboriginal

man. There were also shown some pretty tables painted in groups of native

ferns, wreath of flowers, etc., the handiwork of some Hobarttown ladies.[32]

In fact on 8 May 1876, two days prior to the

Philadelphia opening, Truganini had died. She was buried on 10 May at midnight

at the old convict Female Factory in South Hobart. At that very moment, across

the other side of the globe at nine o’clock in the morning in Philadelphia, the

gates opened to the World’s Fair.[33] One hundred

thousand people attended that day. The Tasmanian photographs on display were

those taken in 1866 at 42 Macquarie Street, the studio of Charles A.

Woolley, for an earlier Melbourne Intercolonial Exhibition. Woolley was

assisted at that time by Louisa Meredith. The suite of portraits was loaned for

the 1876 exhibitions by H.M. Hull, the Clerk of the House of Assembly and

Secretary of the Royal Commission for the Philadelphia Exhibition.[34] That Tasmanian highlight of the World’s Fair was not chosen just at

random by J.S. Ingram for his official publication of the Philadelphia event.

The portraits were not mere curiosities or a courteous inclusion to represent

an otherwise distant and irrelevant place. On the contrary, the pictures were

central to one of the main themes of the entire Philadelphia Exhibition.[35] It was organised around ethnological themes that were presented as

the sturdy base for the idea of American national progress. An exhibition

directive from the Washington Office of Indian Affairs mandated that

photographs of American aborigines, as they were called, were to be collected

and displayed.[36] Accordingly, the Tasmanian Aborigines could thus be measured

directly against the American aborigines.

C.A. Woolley, Portrait of Truganini, 1866 Image courtesy of National Library of Australia, an23378504

In Philadelphia, three hundred Native American

people from 53 nations were also brought to the exhibition. But on 6 July news

reached Philadelphia of the disaster in the Montana Territory at the Little

Bighorn River where General Custer’s cavalry unit was destroyed with 268 killed

by the Lakota Sioux led by Sitting Bull. In Tasmania The

Mercury reported the battle and predicted a ‘war of extermination

against the Red Skins’.[37] American news was prominent in Tasmanian newspapers. The

Philadelphia story, in the wake of the Emancipation proclamation, was all about

industrial progress and national development that met on the intersection of

Victorian anthropology and scientific racism.[38] The Federal

Office of Indian Affairs under John Quincy Smith, a friend of President Grant,

imposed the theoretical framework for the ethnology at the exhibition. It was

adopted from the work of the German anthropologist Gustav Klemm and his theory

of Kulturgeschichte that was directly applied by the Smithsonian curator

Otis T. Mason. Klemm was also the main influence on Edward Burnett Tylor with a

variation of the hypothesis of the three stages of culture—for Klemm these were

savagery, domestication and freedom.[39]

It was Tylor who wrote the preface for Henry Ling

Roth’s book of 1890, The Aborigines of Tasmania, and so the lines of

thought across the continents join again.

The effect of the Philadelphia Exhibition on

ethnology and museums was to be lasting. Both the Smithsonian and the Pitt

Rivers museums adopted similar strategies for curating ethnological exhibits

and that global influence reached the Australian colonies.[40] On a wider scale, Spencer Fullerton Baird of the Smithsonian

Institute acquired all the exhibition materials and shipped them to Washington

in forty rail cars. After Philadelphia the Smithsonian added a new museum,

called the National Museum in which much of the material was housed. The

National Museum was proposed by President Grant and funded by Congress. The

same thing happened in Chicago in 1893. The Chicago exhibition gave the world

the Ferris wheel, Wrigley’s chewing gum, Frederick Jackson Turner’s ‘frontier

thesis’ and it hosted Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. As a direct consequence of

the 1893 exhibition Chicago got the Field Museum as well as skyscrapers. Indeed

both American exhibitions followed the lead of the Great Exhibition of 1851

when the South Kensington Museum was established, now called the Victoria and

Albert. The Smithsonian still retains a few Tasmanian items from 1876,

including the handiwork of Louisa Meredith and a painting of Avoca by Mrs H.M.

Hull, wife of the Secretary to the Tasmanian commission.

Conclusion

The fate of the American Club in Hobart is not

known[41] but we do know what happened to Clark.

Two years later, in 1878, he was a member of the Tasmanian Parliament whilst

denounced as a republican and a communist by The Mercury

that had not forgotten his 1874 essay on the French Republic. The Mercury imputed the republicanism of the 1871 Paris

Commune to Clark rather than that of the American naval officers of the Swatara or the enthusiasms of the 1876 Centennial, or the

republicanism of Jefferson, Madison or Lincoln or Whitman or Thoreau or

Emerson.

The importance and lasting influence of Clark’s

American political ideas have been traced since his own lifetime and appear to

hold the interest of generations of Australian historians. However, a good deal

of work yet remains to be done in that vein. This paper of course represents a

retrospective and rather expansive reading of a small dinner amongst friends in

Hobart in 1876. In the technical realms of historical method the argument here

may appear to fall into the sins of teleology and historicism—of seeming to

inflate historical moments by, as it were, reading history backwards. The

intention of the paper is rather to develop the context for the early

development of political ideals that Clark took from the United States and to

show how Tasmania was connected to the rest of the world or at least to

significant parts of the world that were on the rise. Clark was highly unusual

in his time and place. From the 1870s he looked from Tasmania across the

Pacific. In the main, his elders and contemporaries still thought that from the

vantage point of home the United States lay across the Atlantic.

[1] The Mercury (Hobart), 16

November 1907, p. 8. Alas, the identity of Jacques remains obscure. He was

clearly an experienced local political participant and long-time associate of

Clark, perhaps a man of many parts. Without any knowledge of Jacques’ identity

the inspiration for the pen name is a matter of speculation but a likely

candidate is the melancholic observer of life in As You Like

It for whom, ‘All the World’s a Stage / And men and women merely players

/ They have their exits and their entrances ...’.

[2] As it happens Clark’s father-in-law, John Ross, the

Hobart shipbuilder, was a native of Nova Scotia and he may have had books about

North America to which Clark had access.

[3] The Mercury (Hobart), 13 May

1876, p. 3. Monsieur Beaurepaire also advised patrons and friends in his

advertisement that luncheon is available from 1 pm and ‘French Café and Dinner

Parties attended to at any time’.

[4] Bowen was the New Zealand Governor from 5 February 1868

to 19 March 1873 and Fergusson from 14 June 1873 to 3 December 1874. On 4 March

1874 a dejeuner was given by the citizens of

Wellington to his Excellency Mr F.A. Weld, Governor of Western Australia. Evening Post (NZ), 4 March 1874.

[5] On Monday 15 May 1876 Monsieur Beaurepaire paid £4 for

the concession to the committee rooms booth and bar at the public auction of

catering booths for the Queen’s Birthday race meeting at Elwick (8 booths in

total were auctioned). Henn and Co paid £1 for the right to publish the

official program (also publisher of the Quadrilateral).

Cornwall Chronicle, 17 May 1876.

[6] John Reynolds reproduces the speech in his paper ‘A. I.

Clerk’s American sympathies and his influence on Australian federation’, Australian Law Review, vol. 32, no. 3, 1958, pp. 62–75.

Clark stated in his presidential address that the 1876 event was the fourth

such gathering.

[7] H. Reynolds, ‘Clark, Andrew Inglis (1848–1907)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol. 3, Melbourne

University Press, Carlton, Vic., 1969; Launceston Examiner,

5 July 1878, p. 2.

[8] Contemporary works on Jefferson to which Clark likely

had access were: George Bancroft, History of the United

States; Henry S. Randall, The Life of Thomas

Jefferson, 1871; Samuel Schmucker, The Life and Times

of Thomas Jefferson, 1857.

[9] John Reynolds, op. cit., p. 62

[10] Garry Wills, Lincoln at Gettysburg:

The Words That Remade America, Simon and Schuster, Riverside, 1992.

Lincoln according to Wills greatly admired the prose style of General Ulysses

S. Grant who wrote clear, precise, concise orders from the saddle as he

prosecuted the war.

[11] Mary Astell, Some Reflections upon

Marriage Occasion’d by the Duke and Duchess of Mazarine’s Case Which is Also

Consider’d, John Nutt Stationers Hall, London, 1700, p. 65.

[12] The

notorious flogging of Martha Hudson created an administrative crisis for

Lieutenant Governor David Collins. The Magistrate G.P. Harris who saw the

incident and questioned Lieutenant Lord was immediately placed under arrest for

defiance of military authority. This situation exposed an almost impossible

contradiction between military and civil authority at the same unsteady time

that Governor Bligh was overthrown in Sydney. The controversy followed both

Collins and Harris to their early graves in 1810. The corrupt and brutal Edward

Lord would become the richest man in Van Diemen’s Land. John Currey, David Collins: A Colonial Life, Miengunyah Press, Carlton,

Vic., 2000, pp. 269–70. Barbara Hamilton-Arnold (ed.), Letters

of G. P. Harris 1803–1812, Arden Press, Sorrento, 1994, pp. 105–15.

[13] The Tasmanian electoral roll of 1914 shows three women by

the name of Martha Hudson, two in the division of Bass and one in Franklin

[14] Bentham’s proposition about the utility of the penal

system was that it would ‘grind rogues honest’.

[15] Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, ‘The

Incommodities of Such a War’

[16] Phillip Henry, ‘Christ is our Life’, Sermon X in Miscellaneous Works of Rev. Matthew Henry, vol. 2, Joseph

Ogle Robinson, London, 1833, Appendix p. 30.

[17] Edward Irving, Exposition of the Book

of Revelation, vol. 3, Baldwin and Craddock, Paternoster Row, 1831, p.

1145.

[18] The frontispiece quote to His Natural

Life (1874) carries the following passage: ‘It is apparently your

opinion that Transportation may be made one of the most horrible punishments

that the human mind ever depicted?’ – ‘It is in my opinion that it may be made

more terrible than death’. Evidence of Sir Frances Forbes before the Select

Committee on Transportation of the British House of Commons, 28 April 1837,

Q1347.

[19] ‘Let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia and

Lookout Mountain of Tennessee ... from every mountain side. Let freedom ring’. In

1963 Martin Luther King tied the landscape of the United States to its ‘true

creed that we hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created

equal’.

[20] David M. Robinson, Natural Life:

Thoreau’s Worldly Transcendentalism, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY,

2004, p. 1.

[21] H.A. Page’s book Thoreau: His Life and

Aims was sold by the Hobart stationer Walch and Birchall in 1879 for 3s

6d.

[22] Robert W. Rydell, All the World’s a

Fair: Visions of Empire at American International Exhibitions 1876–1916,

Chicago University Press, Chicago, 1984.

[23] Lieselotte Overvold, ‘Wagner’s American Centennial March:

genesis and reception’ Monatshefte, vol. 68, no. 2,

1976, pp. 179–87.

[24] As reported in The Mercury, 18

February 1875, p. 2. The Swatara arrived in Hobart on

3 October 1874, one of the main places identified by the US Navy. Two

observation posts were established, one in Hobart and one in Campbell Town.

[25] The Mercury (Hobart), 25 November 1874, p. 2. ‘Over the

principal entrance, and the entrance to the ante room, stars of bayonets and

swords were placed which had the effect of greatly enhancing the novelty of the

scene’. In the centre of the main table was a memento of the visit of the

officers of the Swatara in the shape of a cake

‘surmounted by an eagle and a bannerette, with two flags on each side, the word

“welcome” inscribed thereon’. The decorations were mounted under the

supervision of Mr Thomas Whitesides and the Quartermaster of the Swatara. Captain Chandler participated in the first dance

and he took the central seat at the supper table. A gushing address about the

excellence of appointed governors was made by the Chairman of proceedings, Sir

Robert Officer, the Speaker of the House of Assembly, which was surely not

intended as a slight on political systems with elective governors. There was

bunting everywhere.

[26] The crew of the Swatara was

celebrated when on 9 October a heavy squall hit Hobart and a local boat had to

be regained by the American crew. The Mercury reported

in the same article that Mr Clark’s cab that was left in front of his house in

Collins Street was blown across the road by the high winds and in consequence a

pole was smashed. The Mercury (Hobart), 10 October

1874, p. 2.

[27] The Mercury (Hobart), 25

November 1874, p. 2.

[28] Andrew Inglis Clark was later invited to viceregal levees

on 25 May 1879. See The Mercury (Hobart), 9 June

1879, supplement, p. 1 and Governor Weld’s farewell, The

Mercury, 7 April 1880.

[29] Sir Redmond Barry was here appointed for the fifth time

as the commissar for such exhibitions.

[30] Tasmanian contributions to the Intercolonial Exhibition,

Melbourne, 1875, and the Philadelphia International Exhibition, 1876,

Government Printer, Hobart, 1875.

[31] The US Consul General Thomas Adamson was visiting Sydney

and more guests would have attended but for the opening of the Deniliquin–Moama

railway. The Argus (Melbourne), 5 July 1876, p. 6.

[32] J.S. Ingram, The Centennial

Exhibition, Described and Illustrated: Being a Concise and Graphic Description

of this Grand Enterprise Commemorative of the First Centenary of American

Independence, Hubbard Bros, Philadelphia, 1876, pp. 425–6.

[33] Mindful that in 1876 there was no world time as such. The

International Meridian Conference of 1884 in Washington DC saw the adoption of

Greenwich Mean Time. Tasmania moved to an Australian standard eastern time in

1895.

[34] Cornwall Chronicle, 19 December

1866. Woolley won a tender to take the photographs for £10 assisted by Mrs

Meredith. The Aborigines were given permission by the government to come up

from Oyster Cove. The Mercury (Hobart), 6 June 1866.

Three pictures were taken of each subject: full face, side face and profile. The Mercury (Hobart), 12 September 1866.

[35] The Mercury (Hobart), 7 August

1875.

[36] Otis T. Mason, Ethnological Directions

Relative to Indian Tribes of the United States, Government Printing

Office, Washington, 1875.

[37] ‘American Indian Massacre’, The

Mercury (Hobart), 26 August 1876, p. 3. The Cornwall

Chronicle and the Examiner also reported the

story.

[38] John Wesley Powell, who had surveyed for the railroad

across the Rockies, was given a collecting role for the Philadelphia Exhibition

for native materials in the west.

[39] Ingram, op. cit., p. 22. For a discussion of Klemm, see

Chris Manias, ‘The growth of race and culture in nineteenth century Germany:

Gustav Klemm and the universal history of humanity’, Modern

Intellectual History, vol. 9, no. 1, April 2012, pp. 1–31.

[40] For a fine survey of the period see George W. Stocking, Victorian Anthropology, Free Press, New York, 1987.

[41] The club appears to have lasted until at least 1878, when

the Examiner reported a meeting noting ‘the peculiar

opinions’ of those who attended (Launceston Examiner,

5 July 1878, p. 2).

Prev | Contents | Next