Papers on Parliament No. 59

April 2013

Ross McMullin 'Will Dyson: Australia’s Radical Genius'

Prev | Contents | Next

I will start with a true story about how I first came across Will Dyson many years ago. I was doing research on a project about the First World War that led me to study Australia’s war art. One day, at the Australian War Memorial’s research centre, I was given a file to look at about Dyson the war artist. A letter in the file jumped out at me. Dyson was not impressed by the proposed distribution of his war lithographs:

I see that the State Governors of Australia have been included in the list of recipients ... In the name of the digger I protest ... [I don’t want them given] to the collection of poor relations and broken winded English party hacks out to grass that make up the State Governors.[1]

That letter made me sit up. Here was someone interesting I wanted to find out more about. What I discovered was that Will Dyson was a remarkably talented and versatile artist–writer.

He was a brilliant and forceful cartoonist. Australia has been blessed with plenty of outstanding cartoonists, but Dyson was right up there with the best of them.

He was our first official war artist. Many artists followed Dyson in the First World War and later conflicts, but I am not alone in believing that he remains our finest ever war artist as well as our first.

Dyson was also a sublime writer of prose and poetry. He wrote about Australia’s soldiers as superbly as he drew them.

He took up etching in his later 40s, and won international acclaim in this field also.

Besides all this, he was an instinctive radical with dazzling wit and a convivial personality. He married Ruby Lindsay and knew all her famous artist brothers well—Norman, Lionel, Daryl and Percy Lindsay.

Dyson was described in his heyday as the most famous Australian in the world. He should be much better known today than he is.

But the Will Dyson story is not just a celebration of fame and achievement. It is about a sensitive soul, the ups and downs of a sentimental larrikin.

It is partly a love story.

It is about his love for Australia’s soldiers. ‘I never cease to marvel, admire and love with an absolutely uncritical love our louse ridden diggers’, he declared.[2] He produced hundreds of Western Front drawings of profound empathy and sympathy and was wounded twice in the process. Dyson’s reverence for Australia’s soldiers, their perseverance and exploits, was enduring.

It is about his love for his country. Will Dyson was born in Ballarat, grew up in Melbourne, and had a profound sense of attachment to his homeland even though he had to venture overseas to make his mark. But this connection frayed. In 1929 he lamented that Australia had become ‘a backwater, a paradise for dull boring mediocrities, a place where the artist or [someone] with ideas could only live on sufferance’.[3] The ‘guidance of the country [had fallen] into the hands of rich drapers, financial entrepreneurs, newspaper owners, people who in other countries were kept in their place’.[4] Australians might have a reputation as hardy pioneers and explorers, he said, but what was overdue was some serious exploring of ‘our great empty mental spaces’.[5] In his final years he was describing Australia as ‘a beautiful country to die in’.[6]

And it is about his love for Ruby Lindsay.

In October 1918, nine years after their marriage, Dyson wrote that ‘never by any circumstance moral or physical did I deserve the wife I got’.[7] This was a love that never died, even after Ruby died.

As well as being in a number of ways a story about love, it is also a story about hate.

Dyson revered Australia’s soldiers and their achievements, but he utterly detested war. ‘I’ll never draw a line to show war except as the filthy business it is’, he told his friend Charles Bean, the Australian official correspondent at the Western Front.[8] Dyson found the many months he spent at the Western Front harrowing for more than the obvious reasons.

Bean observed that Dyson experienced at least ten times more of the real Western Front than any other official artist, British or Australian. But it was not just the horrors and dangers that left Dyson feeling ripped apart. He felt inspired by the Australian soldiers’ endurance and accomplishments, but at the same time he felt dismayed that a fine Australian generation was being destroyed before his eyes.

And further on hate, the ferocity Dyson displayed as a cartoonist stemmed from his loathing of suffering, inequality and flagrant social abuses.

His friend G.D.H. Cole said Dyson ‘hated the things a decent man ought to hate—oppression and snobbery and cruelty and highfalutin nonsense’.[9]

This is also the story of a brilliant creative artist, a genius, who concerned himself with important issues affecting art, politics and society without ever losing his sense of fun.

Dyson was convivial, amusing and a natural comic performer. He had a striking flair with words, evident in his witty cartoon captions, sparkling after-dinner speeches and scintillating conversation.

He would dash off a letter on a long ship voyage saying ‘Today is Sunday but it is so like any other day that it would take a learned theologian to tell the difference’. At the famous Café Royal in London he entertained onlookers by pretending to carry on conversations in a variety of European languages that sounded exactly like the real thing when the only language he actually knew was English. If asked to provide a receipt he would write ‘I am graciously pleased to confer upon the above mentioned sum the distinction of having been received by me.’[10]

He would give an after-dinner speech to a gathering of Australian artists welcoming him home by saying ‘England [used to] send criminals to Australia, and we retaliated by sending artists to England’.[11] At this time he also remarked that ‘My work in London was finished ... There was no further use in continuing to live on the outer fringes of Empire—I resolved to return to the passionate throbbing life at its centre. I have bought a house at Moonee Ponds.’[12] This was of course well before Edna Everage made Moonee Ponds internationally renowned.

And Dyson and his friend Jimmy Bancks, the creator of Ginger Meggs, often used to amuse themselves on a train in the following way. One of them would open a window and the other would promptly close it. A swiftly escalating exchange of insults would follow, to the alarm of other passengers. Just when it seemed that a nasty fight was about to commence, Dyson would ask Bancks which school he attended, Bancks would concoct a likely-sounding but non-existent institution in reply, and Dyson’s attitude would transform in an instant. ‘Why, that was my school—this would not have happened if you had been wearing the old school tie!’ With that he would vigorously shake Bancks’s hand, apologise profusely, and concede: ‘Have the window any way you want it, dear old chap!’

Will Dyson was born at Ballarat in 1880. Some years later his family moved to Melbourne. As he grew up the biggest influence on his development was his eldest brother Ted. Edward Dyson was a well-known and remarkably prolific freelance journalist and writer who was fifteen years older than Will (who was known as Bill by everyone who knew him well). Between Ted and Bill among the siblings was another prominent creative brother, Ambrose Dyson, a capable professional cartoonist. There was creative talent among Bill’s sisters too.

After the Dysons moved to Melbourne they became close friends with another remarkably talented family, the Lindsays of Creswick.

The Dysons and the Lindsays had plenty in common. Art and girls, books and boxing. Learning to draw, yearning for talk, searching for fun. They were prominent in bohemian groups such as the Prehistoric Order of Cannibals and the Ishmael Club. Bill Dyson’s closest friend was Norman Lindsay.

Bill first became noticed as a caricaturist.

He would prowl city streets stalking his prey, looking for quirks of character, mannerism and dress. Some of his targets became perturbed by his pursuit. There are reproductions in the book of his brilliant and penetrating caricatures of identities as diverse as Henry Lawson, John Wren, and Victorian premier Tommy Bent, the notorious rogue who reportedly declared to a journalist: ‘I know what you’re going to say against me, Mr Carey. You’re going to say that I have a wife and family in every suburb and that I neglect them. I don’t neglect them, Mr Carey.’[13]

Another Will Dyson caricature that is often reproduced is his drawing of Labor MP King O’Malley.

Bill and Norman had similar interests and were determined to be artists, but had very different priorities in their work. For Norman, his weekly cartoon for the Bulletin was a chore to be dashed off as quickly as possible before he returned to what he regarded as the real work that mattered far more to him. For his Bulletin cartoons, he was happy to do what the editors wanted: instructions were welcome, the subject matter did not matter, and whether it was right-wing or left-wing by and large he did not care.

Dyson’s attitude to cartooning was very different. He was a radical, a supporter of left-wing causes and issues. Receiving instructions about what kind of political cartoon to draw was absolute anathema to him. He would pace up and down, developing his ideas or honing a caption for a drawing, just like the traditional genius at work. Nothing annoyed him more than editors altering his work.

Despite showing conspicuous talent in a range of spheres—caricaturist, cartoonist, writer—Dyson struggled to find a niche in Australia. As an example of the kind of discouragement he had to contend with, Dyson drew a striking caricature of a wealthy Adelaide businessman, mayor and politician named Lewis Cohen. He put considerable effort into devising appropriate captions for his art, and in this instance he came up with one that was clever and hardhitting: ‘The poor man’s friend: A man whose principle is to take great interest in assisting the poor.’ When the caricature was published, however, all the caption said was ‘Mister Cohen. The poor man’s friend’ and Dyson’s forceful caption was lost.

It was this kind of treatment that prompted Dyson to decide to venture to London in 1909 at the age of 29. He was hoping to find a slot in a broader cultural environment. It was a bold step, a real gamble. He married Ruby, and persuaded Norman to go with them.

After a while in London, however, Norman returned to Australia following a big row with Bill. Bill stayed in London with Ruby, and was engaged by the radical London Daily Herald as its cartoonist. This was a big breakthrough, a marvellous opportunity, and he grasped it with relish. The timing was perfect. This was a time of political, industrial and social upheaval in England. Strikes were numerous, suffragettes were militant, politics was turbulent. The Daily Herald gave Dyson editorial freedom and encouraged him to go for the jugular.

He certainly did. Traditionally, English cartoons had lacked vigour and passion. Dyson’s were very different. His angry, rebellious shafts against inequality and suffering were intensely passionate. The Daily Herald maximised their impact with whole-page reproduction. Both workers and intellectuals admired them.

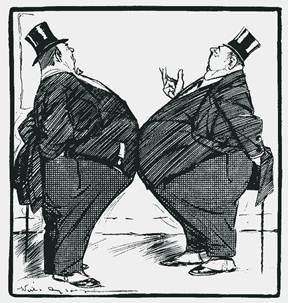

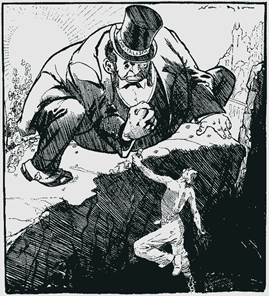

The workers liked Dyson’s boldly drawn figures representing clear symbols of the noble, wronged toiler versus his oppressive employer, who Dyson drew and labelled as ‘Fat’, an evil-looking man in formal dress featuring top hat and spats, with several chins and a huge paunch, sometimes waving a cigar and resting on a pile of moneybags.

The intellectuals savoured Dyson’s wordy, witty captions. G.B. Shaw, G.K. Chesterton and H.G. Wells praised the Australian newcomer as the most brilliant and forceful cartoonist Britain had known for decades. Another Dyson enthusiast declared that the ‘capitalist is not merely drawn—he is quartered ... [in] some of the most passionate, skilful and unmerciful cartoons it has ever been my good fortune to encounter’.[14]

|

|

|

|

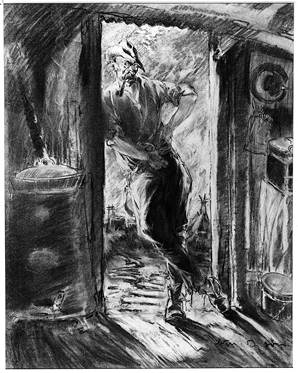

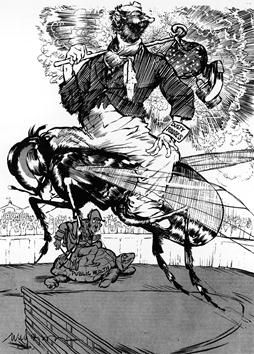

‘Economic Darwinism’, Cartoons (London, 1913)

|

‘Labour Wants a “Place in the Sun” ’, Cartoons (London, 1913)

|

One of my favourite Dyson cartoons of this period showed two of these gross rank Fat men together, with one of them saying to the other: ‘The visionaries and Socialist demagogues may rant against us, my boy, but they can’t alter the divine law of the Survival of the Fattest!’ Dyson called it ‘Economic Darwinism’.

‘Labour Wants a “Place in the Sun” ’ is a typically powerful cartoon of easily grasped symbolism. Dyson’s caption has one of his notorious Fat men (wearing a top hat labelled Capitalism) rebuffing the worker: ‘Back to your abyss, sir! As it is already there is scarcely enough sun to go round!’

Around 1913 Dyson was far from the only radical to be profoundly disillusioned by the ineffectual performance of the British Labour Party. In one cartoon he depicted a number of recognisable British Labour MPs praying for what he felt they seemed to yearn for most—a top hat.

Dyson’s cartoons supported impoverished strugglers and militant suffragettes. In one inventive cartoon he combined both these concerns. With arrested suffragettes going on dedicated hunger strikes for their cause, the authorities responded with brutal enforced feeding. Dyson drew a destitute mother and daughter passing a newspaper placard headlining the latest news about this brutal treatment of the suffragettes. Dyson has the impoverished little girl seeing the placard and saying ‘Mummy, why don’t they forcibly feed us?’

|

|

|

|

‘In the Midlands’, Cartoons (London, 1914)

|

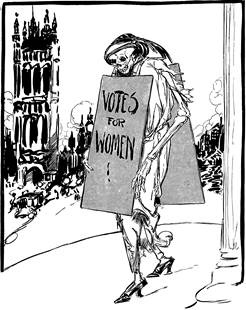

‘The New Advocate: Death of Miss Davison’, Cartoons (London, 1914)

|

When Emily Davison was fatally injured while carrying out a suffragette protest, Dyson responded with a grim cartoon.

Dyson’s Daily Herald cartoons had an astonishing impact. His success was rapid, unforeseen and stunning. The Daily Herald took advantage of Dyson’s spectacular success by producing volumes of his cartoons. Sales were extraordinary. The first print run of 10 000 sold out in three days. The Daily Herald urgently printed another 25 000. The celebrated cartoonist blossomed as a speaker, excelling as an after-dinner speaker and even as a stirring orator at a huge strikers’ rally that generated a capacity audience at the Albert Hall. A well-known Australian journalist working in London described Dyson as the most famous Australian in the world.

For Dyson, life was never better. He and Ruby, whose art had prospered in London, were residing in fashionable Chelsea, suburb of numerous artists. They had become parents with the birth of Betty in 1911.

The First World War smashed this serenity like a wrecking ball demolishing a house. Dyson loathed war, but felt England was entitled to defend itself against German aggression. His response to the outbreak of war was a series of drawings attacking rampant militarism that came to be known as the Kultur cartoons. This was because these cartoons, while expressing a universal anti-militarist message, did so in a way reflecting Dyson’s perception of the immediate context in that the figures representing evil had upturned moustaches and were recognisably Prussian. This was appropriate as far as Dyson was concerned because he felt German aggression was most to blame for the war. But he was to regret his choice of image, because the cartoons were later used for crass propaganda purposes that were repugnant to him.

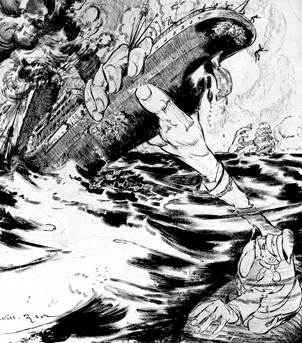

One of them was about Germany’s submarine campaign, and he called it ‘Freedom of the Seize’.

‘Wonders of Science!’ had a big impact on the notorious newspaper proprietor Lord Northcliffe. When he first saw it, he imperiously cancelled the advertising covering the entire back page of his Daily Mail and inserted this drawing instead. It ‘occupies a larger space than any cartoon has ever before been given in a British Newspaper’, claimed the Daily Mail as it waxed lyrical about this ‘young man with the most virile style of any British cartoonist’.[15]

Dyson of course would have scorned any suggestion that he was not fervently Australian, and he was profoundly moved by Australia’s contribution at Gallipoli. He retained a strong sentimental attachment to his homeland. His emotions were further stirred when Australian soldiers became involved at the Western Front in 1916 and soon sustained immense casualties, almost 30 000 in two months. Dyson felt impelled to contribute. He volunteered to go to France and sketch Australian soldiers for posterity, to provide a record of this important part of the national story. His application declared that he wanted ‘to interpret in a series of drawings, for national preservation, the sentiments and special Australian characteristics of our Army’.[16]

|

|

|

|

‘Freedom of the Seize’(1915)

Australian War Memorial ART02256

|

‘Wonders of Science!’, Kultur cartoons,

(London, 1915)

|

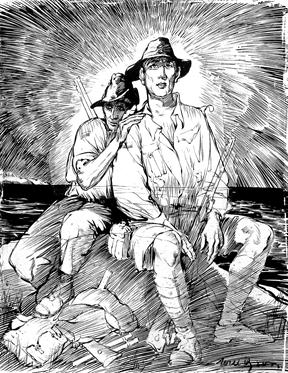

Some Western Front artists gravitated to colourful landscapes or scenes of dramatic action—blood-and-thunder bayonet charges, lethal military hardware, straining horses dragging big guns forward. Dyson’s focus was different. He concentrated on the men.

What he drew in his black and white sketches was much harder to draw—exhaustion and endurance, grit and grime.

He sketched Australians waiting, resting and sleeping. He captured them stumbling out of the line drained and dazed. He drew weariness, perseverance, fatalism.

Dyson was especially stirred by what they did in 1918. In this crucial year the Australian soldiers were influencing the destiny of the world more than Australians had ever done before and more than Australians have ever done since.

On 21 March 1918 the Germans launched an immense offensive that drove the British back no less than 40 miles. Australian units were rushed to the rescue, and were prominently involved in plugging the gaps in the British defences. These were desperate days. For the British, it was the biggest crisis of the war. There was widespread genuine concern that after years of fierce fighting, awful hardships and frightful casualties Britain and its allies might well lose the war.

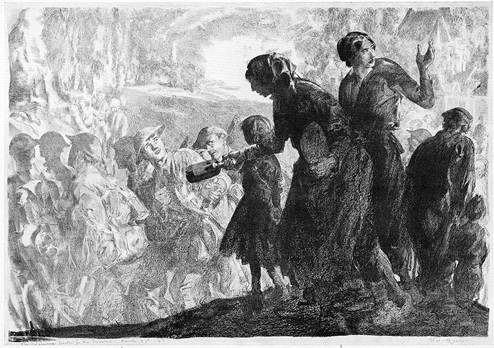

The arrival of Australian formations in vulnerable sectors was inspiring and influential. Distressed French civilians whose homes had been in the path of the German advance were in terrified retreat, struggling along with whatever possessions they could gather or carry in the sudden crisis, typically elderly or women (because the French men were away in the army), often with a crying child clinging to mother’s skirts. And you have got the situation transformed by the arrival of the Australians, confident, unflustered by the dismay all around them, ready to do the business and stop the Germans in the gravest crisis of the greatest war there had ever been.

Many of these retreating civilians recognise the Australian uniform, and they become exultant. They start raving about ‘les Australiens merveilleux’, [‘the marvellous Australians’] and many of them actually turn around and go back to their homes because they are so confident the AIF will stop the Germans. Some of the finest national declarations in Australia’s entire history are to be found here, like the reassuring words of some of these diggers to the distraught French women: ‘Fini retreat madame, beaucoup Australiens ici’. [‘No more retreat madame, many Australians here’] That’s got to be one of the all-time great national statements, surely: ‘Fini retreat madame, beaucoup Australiens ici’.

‘Welcome Back to the Somme’ (1918) Australian War Memorial ART02252.001

Will Dyson depicted these stirring events in a drawing he entitled ‘Welcome Back to the Somme’. He showed Australian soldiers marching towards the fray and being greeted by civilians delighted to see them. The key to the drawing is the raised hand of a woman who is beckoning to other retreating civilians, urging them to turn around and return, as she is doing, to their vacated homes because the Australian soldiers have arrived.

A few weeks later the German advance was threatening the city of Amiens. The sense of crisis for the British was still acute. The important task of safeguarding Villers-Bretonneux, a strategically vital town that overlooked Amiens from the east, was allocated to a British division. On 24 April 1918 the Germans attacked, drove the British out of Villers-Bretonneux, and captured it. Concern about this situation reached the highest levels. Two Australian brigades (one led by that redoubtable commander General Pompey Elliott) were assigned the task of recapturing the town.

Will Dyson and Charles Bean were, typically, on the scene. When they heard about the proposed counter-attack, a complex manoeuvre in the dark without artillery support, Bean was pessimistic, as his diary attests: ‘I don’t believe they have a chance. Went to bed thoroughly depressed ... feeling certain that this hurried attack would fail hopelessly’.[17]

Bean was mistaken. This daring venture on the third anniversary of Anzac Day was brilliantly successful, one of the Australians’ finest exploits, and signalled the end of the dangerous German thrust to Amiens. It intensified Dyson’s worship of Australian soldiers, which was very evident in a letter he wrote to Ted shortly afterwards:

the boys are more eager, cheerfull, bucked up and full of fight than ever before. Weather is good, food is good and they are at the height of their reputation. What they have done is in so striking a contrast to what the others did not do ... God alone knows what terrible things are coming to them, but whatever they are they will meet them as they have met everything in the past. These bad men, these ruffians, who will make the life of Australian magistrates busy when they return with outrages upon all known municipal byelaws and other restrictions upon the free life—they are of the stuff of heroes and are the most important thing on earth at this blessed moment.[18]

Dyson wrote about Australia’s soldiers as superbly as he drew them. What I have just read was a private letter to his brother, but he produced a book called Australia at War that is little known but a classic. In this book Dyson reproduced some of his drawings with a personal inscription on the page alongside.

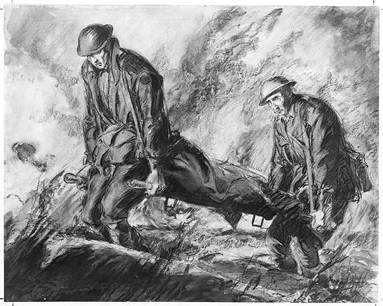

‘Stretcher-Bearers Near Butte de Warlencourt’ (1917)

Australian War Memorial ART02266

To accompany his superb drawing ‘Stretcher-Bearers’, Dyson wrote this:

They move with their stretchers like boats on a slowly tossing sea, rising and falling with the shell riven contours of what was yesterday no man’s land, slipping, sliding, with heels worn raw by the downward suck of the Somme mud. Slow and terribly sure through and over everything, like things that have got neither eyes to see terrible things nor ears to heed them ... The fountains that sprout roaring at their feet fall back to the earth in a lace-work of fragments—the smoke clears and they, momentarily obscured, are moving on as they were moving on before: a piece of mechanism guiltless of the weaknesses of weak flesh, one might say. But to say this is to rob their heroism of its due—of the credit that goes to inclinations conquered and panics subdued down in the privacy of the soul. It is to make their heroism look like a thing they find easy. No man of woman born could find it that. These men and all the men precipitated into the liquescent world of the line are not heroes from choice—they are heroes because someone has got to be heroic. It is to add insult to the injury of this world war to say that the men fighting it find it agreeable or go into it with light hearts.[19]

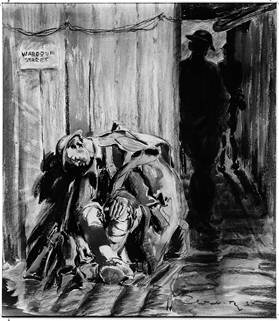

This is what he wrote about ‘Dead Beat’, his drawing of an exhausted young Australian soldier:

He was there as we came back ... I have not drawn him as childish as he looked ... He ... had lost himself and floundered all night in shell holes and mud through the awful rain and wind ... He had floundered into the cover of the tunnel and stopped there, disregarded, save for occasional efforts to assist on the part of the men—attempts that could not penetrate through to his consciousness past the dominating instinct to sleep anywhere, anyhow, and at any cost ... he looked so very young—that quality which here has power to touch the heart of older men in the strongest way. To see going into the line boys whose ingenuous faces recall something of your own boyhood—something of someone you stole fruit with, or fought with or wagged it with through long hot Australian afternoons—to see them in this bloody game and to feel that their mother’s milk is not yet dry upon their mouths.[20]

‘Dead Beat’ (1917) Australian War Memorial ART02210

This is sombre and sobering, appropriately so bearing in mind the context and what Dyson was witnessing and recording. Inevitably, though, being Dyson, he found scope even in these ghastly surroundings for his legendary wit and repartee. He sometimes did amusing drawings as well.

When a machine-gun officer retrieved a drawing Dyson had left near the front line, Dyson drew for this machine-gunner an impromptu thankyou caricature of a bedraggled wet digger. Although it is a quick black and white sketch, the artist’s skill is very evident in the inflamed nose and dripping moustache indicating a heavy cold as this disgruntled digger ploughs through shin-deep mud and slush while rain continues to fall. He is clearly fed up with France in winter. Dyson’s caption has him asking ‘Isn’t there ever any flamin’ droughts in this country?’

|

|

|

|

‘Isn’t there ever any flamin’ droughts in this country’ (c. 1917–1918)

Australian War Memorial ART16157

|

‘The Cook’ (1917)

Australian War Memorial ART02304

|

And Dyson had a thing about quirky military cooks. He depicted them as eccentric in a number of drawings. To accompany his portrait study of one of these cooks, a tough, hardened veteran full of character, Dyson wrote a suitably droll inscription:

I sometimes think it is the primitive emotions of grief and disillusionment and ferocious despair induced by the cooking of the cooks that makes some of our battalions so awe inspiring in the attack ... I have often suspected that Australian units select their cooks not on their ability as chefs but for the stories that can be told about them to other units.[21]

This was not the only kind of writing Dyson did about the Australian soldiers he so admired. He also wrote striking poetry.

As well, Dyson was a member of an informal group that loosely gathered around Bean and included other war correspondents such as Keith Murdoch (father of Rupert) and photographers such as Dyson’s friend George Wilkins. This group influenced numerous decisions affecting Australia’s soldiers. Dyson, with his razor-sharp intellect and conversational sparkle, was a key member of the group.

Among the significant developments Dyson involved himself in were these:

- the controversial question of who should be the chief commander of Australia’s soldiers;

- a program to educate influential visitors about their exploits;

- the creation of a war art scheme involving other artists;

- and, especially, the post-war commemoration of the conflict in Australia.

Under the stars at Pozieres the group discussed Bean’s vision for the institution that became the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. It was Dyson who remarked that battlefield models had been especially evocative in equivalent institutions that he had visited, and his recommendation that they should be a priority for Australia’s memorial was heeded. The upshot was the creation of the superb dioramas that have been such a feature of the Australian War Memorial, and still are today.

Dyson provided the Memorial with over 270 drawings, a unique record of the war experience. Bean thought they were wonderful. He envisaged that the Australian War Memorial would have a special Dyson gallery to display them. But by the time the building of the Memorial was complete, it was 1941 and another world war was under way. Later conflicts have further restricted the Memorial’s capacity to display Dyson’s drawings, so the Dyson gallery never eventuated. However, I am delighted that there might well end up being a special Dyson corner or section in the renovated World War I galleries that are being redesigned at the moment.

Dyson’s months at the front affected him severely. Although a non-combatant, he saw plenty of the real war. Influential businessman W.S. Robinson, one of the distinguished visitors Dyson guided around, described Dyson and his intrepid photographer friend George Wilkins as ‘two of the bravest men I’ve ever met’.[22]

The effect of all this was obvious to Ruby. He ‘looks years older and is very grey’, she observed. ‘I couldn’t get over the change in him last time he came back. The war has altered him a lot poor old Bill’.[23]

Worse was to come for Dyson. In March 1919, when he was just getting used to peacetime and the resumption of domestic life with Ruby and little Betty, Ruby died of Spanish flu.

Dyson was devastated. The eulogies that poured in emphasised the remarkable impression Ruby’s personality, manner and beauty had made on those she met even briefly. Dyson was never the same again. Even managing a partial recovery took him months.

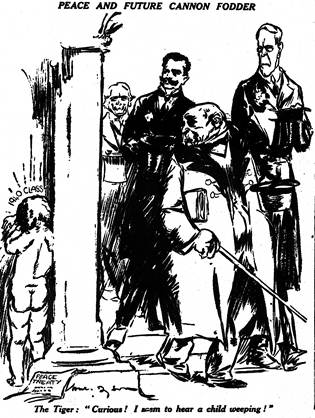

In this mood of bleak despair Dyson drew his most famous cartoon, ‘Peace and Future Cannon Fodder’.

This was his response to the notoriously one-sided Treaty of Versailles. In this 1919 cartoon he predicted not only that this tainted treaty would produce another world war, but also the actual year when hostilities properly began. This remarkably prophetic drawing has been described as one of the most outstanding political cartoons of all time—by any cartoonist, in any country.

Still preoccupied with Ruby’s death, Dyson was intent on producing two books in memory of her. One volume commemorated her art. He called it The Drawings of Ruby Lind. In an introductory tribute he wrote that Ruby’s ‘death came after the Armistice, when it seemed that we might dare to hope again. ... It was as though War before departing utterly from us had added her death as a foot-note, to enrich with a final commentary the tale of his crowded horror.’[24]

The other book consisted of poignant poems Dyson had written since her death. He called it Poems in Memory of a Wife. In one of them, a poem he called ‘Lament’, Dyson berated the ‘griefless Gods’ for ruining his life ‘[t]hat lacking her lacks all that gave it worth’, so that now ‘silence tolls through nights that never end’. He imagined Ruby urging him to stop punishing himself with remorse, assuring him of her knowledge that she would always remain etched in his memory and embodied in Betty. In the final poem, ‘Surrender’, Dyson the poet called on himself to accept the tragedy and cease behaving as if his bereavement was different from countless others since 1914:

Now wrap you in such armour as you may,

And make your tardy peace with suffering,

Since grief must be your housemate to the end ...

Nor is it meet that in these bloody years

Such traffic you should make of common wounds.

What is your grief above our mortal lot

That in a world where all must carry scars,

You clamour to the skies as though were fall’n

A prodigy to earth in this your woe.

Now make your peace, and go as you have gone:

The world was so before this grief befell,

But you, the broken, have in breaking learned

A wisdom that you lacked when you were whole.

... in your veins no flavoured stuff doth flow

That fate should beat upon your head in vain.

... Now bend thee to the yoke,

And teach thy heart no longer to rebel.[25]

The surrender that Dyson is describing is essentially a self-administered anaesthetic to cope with the pain of Ruby’s death. But this deactivating of his ability to feel emotions at their most acute also had an impact on his cartooning. It deprived him of the emotional force that had inspired his best cartoons.

In 1925 he returned to Australia, having accepted a five-year contract to work for the Herald group of publications run by his former Western Front associate Keith Murdoch. In Melbourne he was a prominent cultural and social celebrity. Parties came to life when he arrived. He would often be called on to provide certain celebrated performances such as his imitations of Queen Victoria (with a chamber pot perched precariously on his head) or a South American tribesman calling to his mate. These were such hilarious impersonations that they repeatedly generated helpless tears of laughter among his audiences.

Socially he had a lively time in Melbourne, but professionally his return was less successful. His cartoons were clever, inventive and sometimes vigorous, but lacked the searing power he had consistently displayed before the war.

|

|

|

|

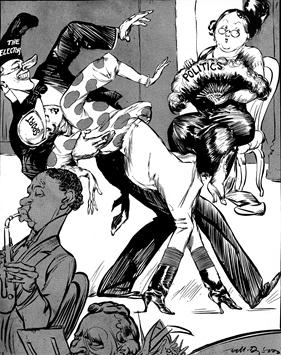

‘Parliament is Sitting (Out) Again’,

State Library of Victoria

|

‘Public Health Also Ran’,

State Library of Victoria

|

One he drew during the 1925 federal election campaign he called ‘Parliament is Sitting (Out) Again’, with the caption: ‘A Comment on Australia’s Much-Deplored Apathy in Regard to Things Political’. Dyson has drawn The Elector preferring to dance with the attractive jockey labelled Sport rather than with the unattractive matron labelled Politics. Whenever I see this cartoon I am reminded that there was a break, a day off, during the 2007 federal election campaign for Melbourne Cup Day. Some things do not change.

Another cartoon that reflects Dyson’s frustration with the sense of priorities Australians displayed was his ‘comment on the increasing attendance of women at wrestling matches’. In this drawing of a wrestling bout, a fierce flapper labelled Miss 1927 is opposed to a dainty damsel from a Jane Austen novel (Ideals of 1826). It is a one-sided encounter. He titled it ‘A Fall in Ideals’.

Dyson also drew a graphic criticism of Australia’s public health, which he entitled ‘Public Health Also Ran’. This was a racetrack scene, with the tortoise of public health a long way behind a repulsive fly ridden by its unwashed swagman named Dusty Rhodes.

There was also a cleverly conceived cartoon about industrial relations. The matronly figure labelled ‘Law’ knits away at her ‘red tape’ while the younger female ‘Employer’ calls to the young male trade unionist: ‘Couldn’t we get on better together if she were not here?’ Dyson’s brilliant title is ‘The Mar-in-Law’.

‘The Mar-in Law’, State Library of Victoria

Dyson was struggling to come to grips with postwar Australia, aftermath Australia. He had returned to a scarred, chastened Australia that had paid a terrible price for its eager enthusiasm to participate in the Great War. This profound legacy was economic, social, political and cultural. There was also a profound emotional legacy. As Bill Gammage put it: ‘Dreams abandoned, lives without purpose, women without husbands, families without family life, one long national funeral for a generation and more after 1918’.[26]

Dyson responded to this emotional legacy sympathetically in his work. Each Anzac Day and Armistice Day a stirring new Dyson cartoon and stirring new verse from his friend C.J. Dennis appeared prominently in the Herald side by side.

On Anzac Day 1927 Dyson’s moving drawing called ‘A Voice from Anzac’ had such an immense impact that the Herald printed a thousand copies of it.

But the legacy of the war shaped Australia in ways that Dyson deplored. In Australia, in the mid-1920s, forward-looking, visionary idealism was scarce. Complacent conservatism with a materialist emphasis was the dominant political ethos, epitomised by the Bruce Government’s focus on men, money and markets. The pre-1914 era of Australia as a pioneering social laboratory was long gone.

Dyson was disenchanted with postwar Australia politically and socially, but especially frustrated with it culturally. After being accustomed to having his say on a big international stage, Dyson found Melbourne restrictive and parochial. One day at the Herald office he came across playwright Louis Esson talking earnestly to a senior writer. Dyson interrupted: ‘If you say anything intelligent in this place, I’ll tell on yer!’[27]

Partly out of frustration, he embarked in his later 40s on a new art form, etching. He proceeded to make a pronounced success of this as well. Whatever Will Dyson did he did well.

When he took his satirical etchings overseas, they were acclaimed in America and England. At that time America was grappling with the issue of prohibition. Dyson thought the solution was simple. What the Americans should do is apply psychology to the problem and ban soft drinks instead. It ‘should be obvious even to a legislator’, he said.[28]

By now the Great Depression had arrived. One of his etchings was a devastating comment on the miseries of the Depression. It depicted a dazed, downcast representation of God lamenting to a forlorn Christ beside him: ‘My son, alas! We are powerless, the bankers have spoken’.

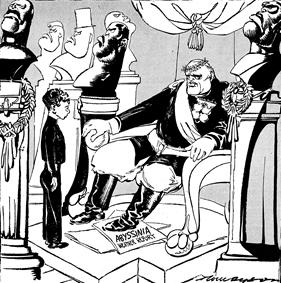

Mussolini was at times frustrated that his forces did not progress in Abyssinia rapidly enough, and Dyson has drawn the all-powerful dictator being asked by an innocent boy ‘But, Duce, can’t you stop the rains?’ I really like the pained expression on Mussolini’s face.

Dyson also provided superbly inventive drawings about that other international crisis, the Bodyline cricket controversy.

Dyson followed the controversy from England with intense interest. In one of his cartoons an Australian batsman, injured but defiant, is arriving to present his Leg Theory Protest at the League of Nations Council. With bemused delegates from China and Persia looking on, the Australian is shown energising an attendant: ‘Tell ’em I’m here, Cobber. It’s urgent!’ The cartoonist signed this drawing ‘Will Dyson of Wagga-Wagga’.

During the 1930s Dyson drew numerous cartoons stressing the evil of war and the folly of rearmament. There was one that simultaneously covered concern about inflation and concern about rearmament:

‘Daddy, what makes the cost of living go up?’

‘The cost of dying, my son.’

Someone who knew him well in this period told me that even as an experienced cartoonist there was always an air of tension about him. Each morning a batch of newspapers and the daily supply of cigarettes would be delivered, he would tensely search the papers for ideas, and pressure would build until he devised and drew his cartoon in time for the next morning’s Daily Herald.

Will Dyson died in January 1938, aged 57, of heart trouble. Too many gaspers. His friend Nettie Palmer wrote that ‘something extraordinarily vital and irreplaceable has gone out of the world’ and reiterated that Dyson was a genius.[29]

Dyson’s art lived on after him. His cartooning influenced later Australian cartoonists despite the fact that he only lived in Australia for five years after he became famous as a cartoonist. The modern communications we take for granted these days did not of course exist back then, so it was not easy for Dyson’s contemporaries to fully appreciate how extraordinarily successful he rapidly became as a cartoonist overseas. Some realised, though—Dyson’s friend Hal Gye, a talented cartoonist who illustrated The Sentimental Bloke by C.J. Dennis, admired Dyson’s spectacular success from afar. Gye wrote this: ‘How I enjoyed his fat, opulent-looking, bloated blokes; how I liked the dynamic technique of ‘em; the stinging captions—world-fame, and an Australian’.[30]

Dyson’s work continued to influence later cartoonists. Two of his nephews became noted cartoonists, and he was naturally a strong influence on their work and progress.

Although Dyson’s significance has been very under-recognised in Australia overall since his death, it is a different state of affairs with cartoonists. When I mixed with cartoonists in the course of my work on the book, I was struck by the way they revere him. In 2006 I did a combined event for the Sydney Writers’ Festival with Bill Leak, and he could not praise Dyson highly enough: he went into raptures about the quality of Dyson’s work. More recently, in 2009, the Australian Cartoonists Association decided to set up a Hall of Fame for the greatest Australian cartoonists of all time, and they appropriately inducted Dyson as one of its initial members.

Question — I was very struck with what you said about that extraordinary cartoon where he predicted the Second World War, even to the date. That was absolutely remarkable and you said it was one of the most famous cartoons of all time. Has it been recognised by historians as something really special in terms of political prediction?

Ross McMullin — Yes. They decided to mark the turn of the millennium with a competition where people assessed what were the greatest cartoons of the twentieth century and that cartoon featured very prominently.

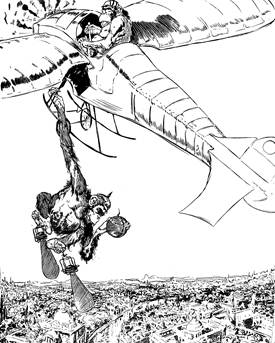

Rosemary Laing — I was struck by the gorilla teetering on top of the tower and wondering how many years later the original King Kong was filmed and whether something that appeared on the back page of a British newspaper might have had an influence.

Ross McMullin — Yes, well Dyson was given the whole page for those pre–World War I cartoons. Compared to how Dyson had struggled to find a niche in Australia beforehand, it was a remarkable turnaround in a very quick time.

Rosemary Laing — Perhaps some young set designer, later to have a career in Hollywood, remembered that and it became the climax of the movie.

Ross McMullin — It was extraordinary to go that quickly from a position I have described to then become someone who was on the spot and well-credentialled to make the comment that he was the most famous Australian in the world. It was a remarkable transformation, even though I think it could be said that Victor Trumper might have had his claims at that particular time, although Victor Trumper probably was not that big in America.

* This paper was presented as a lecture in the Senate Occasional Lecture Series at Parliament House, Canberra, on 19 October 2012.

[1] Letter, Will Dyson to A. Box, n.d., Australian War Memorial file 18/7/5.

[2] Ross McMullin, Will Dyson: Australia’s Radical Genius, Scribe, Melbourne, 2006, p. 218.

[3] Nettie Palmer, Fourteen Years: Extracts from a Private Journal 1925–1939, Meanjin Press, Melbourne, 1948, p. 54.

[4] ibid.

[5] McMullin, op. cit., p. 340.

[6] Vance Palmer, ‘Will Dyson’, Meanjin, vol. 8, no. 4, 1949, p. 222.

[7] Letter, Will Dyson to Edward Dyson, n.d. [c. 11 October 1918], Edward Dyson papers, State Library of Victoria, MS 10617.

[8] C.E.W. Bean, Gallipoli Mission, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1948, p. 111.

[9] McMullin, op. cit., p. 411.

[10] ibid., p. 48.

[11] Herald (Melbourne), 9 April 1925.

[12] Home (Sydney), 1 August 1925.

[13] Geoffrey Serle, The Rush to be Rich: A History of the Colony of Victoria, 1883–1889, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1971, p. 265.

[14] Anthony Ludovici, New Age (London), 5 June 1913.

[15] Daily Mail (London), 1 May 1915.

[16] Will Dyson to Official Secretary, Commonwealth of Australia, 1916, AWM 409/9/14.

[17] AWM 38 3DRL 606/108, pp. 23–4.

[18] Will Dyson to Edward Dyson, ‘May’ [c. 20 May 1918], Edward Dyson papers, State Library of Victoria.

[19] Dyson, Australia at War, op. cit., p. 38.

[20] ibid., p. 18.

[21] ibid., p. 20.

[22] W.S. Robinson, If I Remember Rightly: The Memoirs of W.S. Robinson, 1876–1963, Cheshire, Melbourne, 1967, p. 106.

[23] Letter, Ruby Lindsay to Edward Dyson, 8 October 1918, Edward Lindsay papers, State Library of Victoria.

[24] The Drawings of Ruby Lind, Cecil Palmer, London, 1920, p. 10.

[25] Will Dyson, Poems in Memory of a Wife, Cecil Palmer, London, 1919.

[26] Bill Gammage, ‘Was the Great War Australia’s War?’ in Craig Wilcox (ed.), The Great War, Gains and Losses: ANZAC and Empire, Australian War Memorial and Australian National University, Canberra, 1995, p. 6.

[27] Vance Palmer, op. cit., p. 221.

[28] McMullin, op. cit., p. 334.

[29] Nettie Palmer, op. cit., p. 241.

[30] H. Gye, ‘The Dyson Mob’, Chaplin papers, University of Sydney, p. 19.

Prev | Contents | Next