Introductory Info

Date introduced: 19 September 2019

House: House of Representatives

Portfolio: Treasury

Commencement: Schedule 1 commences on the day after Royal Assent. Schedule 2 commences on the first 1 January, 1 April, 1 July or 1 October after Royal Assent. All other sections, on the day after Royal Assent. The amendments do not come into effect until entry into force of the Australia-Israel Convention.

The

Bills Digest at a glance

The Treasury

Laws Amendment (International Tax Agreements) Bill 2019 (the Bill) contains

two schedules.

Summary of the Bill

Schedule 1 of the Bill amends the International

Tax Agreements Act 1953 to give effect to the Convention

between the Government of Australia and the Government of the State of Israel

for the Elimination of Double Taxation with respect to Taxes on Income and the

Prevention of Tax Evasion and Avoidance (herein referred to as the A-I

Tax Convention).

Schedule 2 of the Bill amends the Income Tax

Assessment Act 1997 and the International Tax Agreements Act 1953 to

create a new deemed source rule in domestic law. The new rule has the effect of

deeming income, profits or gains of a non-resident, that are sourced in

Australia under the term of a tax agreement, as being taxable in Australia.

This rule will be automatically applied to future tax treaties rather than

needing to be individually negotiated, as is current practice.

In order for the A-I Tax Convention to become

effective, it will need to be legislated by both the Australian and Israeli

Parliaments. It is for this reason that the Bill is currently before Parliament.

Purpose of

the Bill

The purpose of the Treasury

Laws Amendment (International Tax Agreements) Bill 2019 (the Bill) is to make

necessary amendments to the International Tax

Agreements Act 1953 (ITAA 1953) to give effect to the A-I Tax

Convention.[1]

The Bill enables the Convention to be given force under Australian law before

ratification happens.

The Bill also incorporates a new ‘deemed source rule’ into

the Income Tax

Assessment Act 1997 (ITAA 1997).[2]

Structure of

the Bill

The Bill contains two schedules:

- Schedule 1 implements the A-I Tax Convention into

Australian law and

- Schedule 2 incorporates into the ITAA 1997 a new deemed

source rule.

Background

Australia currently has entered into 45 international tax

treaties[3]

(although the Australia-Greece Tax Convention only focusses on the

taxation of international air transport).[4]

However, given the Australia-Greece Tax Convention is not a full double

tax agreement, it is often stated that Australia has entered into 44 tax

treaties.[5]

Generally, tax conventions (also referred to as double tax

agreements) seek to achieve two main goals:

- the first is to clarify, standardise, and confirm the fiscal

situation of taxpayers who are engaged in commercial, industrial, financial, or

any other activities in other countries through the application by all

countries of common solutions to identical cases of double taxation[6]

- the second is to improve administrative co-operation in tax

matters, notably through exchange of information and assistance in collection

of taxes, for the purpose of preventing tax evasion and avoidance.[7]

To assist in achieving these goals, since 1955 the OECD has

published its Model

Tax Convention on Income and on Capital (the Model Tax Convention). Among

other things, the Model Tax Convention represents a consensus framework,[8]

which countries can use as the basis for concluding or revising bilateral tax conventions,[9]

ensuring a uniform approach to resolving the most common problems that arise in

international taxation.[10]

The OECD notes that the Model Tax Convention:

... plays a crucial role in

removing tax related barriers to cross border trade and investment. It is the

basis for negotiation and application of bilateral tax treaties between

countries, designed to assist business while helping to prevent tax evasion and

avoidance. The OECD Model also provides a means for settling on a uniform basis

the most common problems that arise in the field of international double

taxation.[11]

The Model Tax Convention contains 30 Articles and provides

explanation of and commentary on those articles to assist in their

interpretation. The Model Tax Convention also allows countries to ‘reserve’

their position on certain articles (i.e. it allows countries to state where

they do not agree, or will not incorporate, an Article into their domestic

law). The 2017 Model Tax Convention numbers over 2,600 pages and is directly

relevant to the interpretation of equivalent articles in the A-I Tax

Convention.[12]

History of the

Australia-Israel Tax Convention

On 17 September 2015, Treasurer Joe Hockey issued a press

release stating:

As part of the Government’s ongoing efforts to strengthen and

deepen our relationship with Israel, we are announcing our intention to

commence negotiations on a new Double Taxation Agreement between our two

countries.[13]

Treasurer Hockey also stated that the tax agreement would:

- reduce the incidence of double taxation between the two countries

- present opportunities for Australian businesses to take greater

advantage of Israel’s knowledge-based economy, particularly in the areas of

biotechnology, ICT, education and training and

- encourage Israeli companies to view Australia as a regional base

and supplier of sophisticated goods and services.[14]

On 23 February 2017, the Prime Ministers of Australia and

Israel announced their commitment to conclude a tax treaty in a joint

media statement:

Leaders committed to support the expansion of trade,

investment and commercial links between Australia and Israel, for their mutual

benefit and prosperity. Leaders welcomed the signature of a bilateral Air

Services Agreement facilitating enhanced air links between our countries. They

also welcomed the signing of an MOU between airline companies from both

countries, which will enhance connectivity between Australia and Israel,

expanding business and tourism links. They resolved to work towards concluding

a Double Taxation Agreement which would remove tax impediments to bilateral

economic activity and enhance the integrity of our respective tax

systems. They welcomed the success of the Working Holiday Visa arrangement

in promoting greater tourism flows.[15]

Following several years of negotiations, Australia and

Israel signed the A-I Tax Convention on 28 March 2019.[16]

What is the A-I

Tax Convention?

The A-I Tax Convention is based on the OECD Model

Tax Convention and sets out a number of agreed rules and procedures as to how Australia

and Israel will apply their tax rules in relation to:

- the payment of dividends, interest and royalty expenses from

Australia to Israel (and vice versa)[17]

- fringe benefits provided by an Israeli or Australian employer[18]

and

-

income or profits earned (or sourced) in Australia or Israel

(i.e. providing relief from double taxation).[19]

The A-I Tax Convention also seeks to, amongst other

things:

- create mutual agreement procedures for eliminating double

taxation and resolving conflicts of interpretation of the A-I Tax Convention[20]

- clarify residency rules so as to make it clearer as to when a

person or entity will be a tax resident of each country[21]

- implement exchange of information procedures for exchanging

taxpayer information between the tax administrations of both countries[22]

- outline agreed upon procedures to minimise the chance of fiscal

evasion or unreported income[23]

and

- detail procedural frameworks and processes for resolving tax

disputes.[24]

Why is

Australia entering a tax treaty with Israel?

The National

Interest Analysis of the A-I Tax Convention outlines a number of

reasons as to why Australia should enter into a tax treaty with Israel. These

are summarised below:

- reducing barriers to investment and trade: it is anticipated that

the A-I Tax Convention will remove barriers for Australian and Israeli

businesses undertaking business activities in both countries. In particular,

Australian business should be more easily able to access Israeli intellectual

property as a result of reduced royalty withholding tax rates

-

increased certainty and reduced compliance costs for taxpayers: it

is expected that removing the incidence of double taxation will reduce

uncertainty around tax outcomes as well as reduce compliance costs associated

with preparing and lodging tax returns in multiple jurisdictions and

-

establishing a more effective framework to prevent international

fiscal evasion and avoidance: the A-I Tax Convention directly

incorporates a number of Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) recommendations,

including rules to prevent treaty shopping and to facilitate greater

co-operation between Australian and Israeli tax authorities and a formal

process for the exchange of taxpayer information between Australia and Israel.[25]

It should also be noted that Israel was the third most

popular destination for disclosures made under Project

DO-IT,[26]

totalling 231 disclosures.[27]

Why does the

A-I Tax Convention need to be legislated?

The general position under Australian law is that treaties

which Australia has joined or signed are not directly and automatically

incorporated into Australian law. Signature and ratification do not, of

themselves, make treaties operative domestically. Treaty obligations need to be

incorporated into Australian law, thus enabling legislation is necessary to

implement and render those obligations operative and enforceable under

Australian law.

If new legislation is required to implement the treaty, the

normal practice is to require that it be passed before Australia brings the

treaty into force. This is because subsequent Parliamentary passage of the

necessary legislation cannot be presumed, entailing a risk that Australia could

find itself legally bound by an international obligation which it could not

fulfil.[28]

As noted by the Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill, the

effect of the amendments to the International Tax Agreements Act 1953 will

be to give the provisions of the A-I Tax Convention priority over

provisions of the Income Tax Assessment Acts 1936 and 1997, Fringe

Benefits Tax Act 1986, and any imposition Acts (except to the extent there

are anti-avoidance rules contained in these Acts).[29]

The new

deemed source rule

In Federal

Commissioner of Taxation v Mitchum[30]

the High Court held that, notwithstanding the text of a treaty, Australia was

not able to tax income unless that income was sourced in Australia. As such, it

has become preferred practice for Australia’s tax treaties to include a

specific Article that provides that where income, profits or gains are

allocated to Australia under the terms of the treaty, those profits, incomes or

gains will be deemed to be sourced in Australia.[31]

As such, this means that in each instance a tax treaty is entered into,

Australia must either individually negotiate the inclusion of this rule or

legislate an equivalent source rule for the treaty in the ITAA 1953.[32]

Schedule 2 of the Bill enshrines this position into

law for all treaties entered into on or after 28 March 2019.

As stated in the Explanatory Memorandum, this will not

affect existing treaties as the new rule will be prospective and in any event

existing tax conventions are already subject to a deemed source rule.[33]

Committee

consideration

Senate Standing Committee for the Selection of Bills

The Senate Standing Committee for the Selection of Bills recommended

that the Bill should not be referred to a committee for inquiry.[34]

Senate Standing

Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

The Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills had

no comment on the Bill.[35]

Joint Standing Committee on

Treaties

Report

187: Oil Stock Contracts—Hungary; MRA UK; Trade in Wine UK; MH17 Netherlands;

Air Services: Thailand, Timor–Leste, PNG; Work Diplomatic Families—Italy;

Double Taxation—Israel (Report 187) of the Joint Standing Committee on

Treaties (JSCOT) included its consideration on the A-I Tax Convention at

pages 57 to 66.

JSCOT supported the A-I Tax Convention between

Australia and Israel and in Recommendation 6 of Report 187 recommends that

binding treaty action be taken:

The Committee notes that the Convention adds to Australia’s

existing network of 44 tax treaties and is consistent with Australia’s

established treaty practice, including that it reflects multiple OECD model

conventions.

Specifically, the Committee acknowledges the benefits of the

Convention reducing tax barriers for Australian and Israeli individuals and

businesses, as well as enhancing the integrity of cross-border dealings by

preventing tax evasion and avoidance.

The Committee supports the Convention and recommends that

binding treaty action be taken.[36]

Position of

major interest groups

The A-I Tax Convention appears to be supported by Australian

and Israeli business groups, with a general theme being that it will better

facilitate Australia-Israel business ties and open up further bilateral trade

and investment. For example, the Australia-Israel Chamber of

Commerce (AICC) is supportive of the A-I Tax Convention, with

national chairman Leon Kempler stating there is ‘tremendous excitement’ within

Israel and Australian industry about the prospect of a tax treaty[37]

and that the A-I Tax Convention will:

... strengthen economic and financial links between Australia

and Israel, provide greater investment certainty and reduce the cost of doing

business. There are now 20 Israeli companies listed on the ASX and we expect

more to list in the coming months. [38]

The Israeli embassy also expects the A-I Tax Convention

will lead to more Israeli companies listing on the ASX, with Israeli Embassy

spokesperson Eman Amasha reported as stating:

Overall, this agreement represents the strengthening trade

ties between Israel and Australia and provides a platform for the further

growth of business operations and investment cooperation in both markets.[39]

These views are also shared by Executive Council of

Australian Jewry president Robert Goot who

was reported as stating that the treaty would improve trade and investment

by removing tax barriers.[40]

Australian law firm Arnold

Bloch Leibler also supports the A-I Tax Convention, contending:

Existing trade between the countries is worth over $1 billion

in addition to cross-border investment. In recent years, many Israeli based

companies have chosen to list on the ASX in order to diversify their access to

capital and take advantage of the superior liquidity offered by the Australian

market. At present there are 20 Israeli companies listed on the ASX, rivalling

the United Kingdom’s 29 (the UK currently being the dominant destination for

Israeli investment in Europe). We expect this number to rise.

The new treaty will promote further trade and investment

between the two countries, and gives Australia a position alongside other Asian

trading partners such as China, India and Japan with whom Israel already has

double taxation agreements.[41]

Ben

Butler writing in the Weekend Australian also considered that the A-I Tax

Convention could benefit Australian businesses looking to expand into

Israel:

A treaty that

eliminated the double taxation of profits between the two countries would be

good news for Australian companies and individuals seeking to invest in Israel

such as Seek co-founder Paul Bassat’s tech fund, Square Peg Capital, and James

Packer of Crown Resorts, who now lives amid speculation the [Israeli] government

will legalise casinos.[42]

Financial

implications

The Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill states that the

Bill is ‘expected to have an unquantifiable cost to revenue over the forward

estimates’.[43]

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed the

Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or declared

in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The

Government considers that the Bill is compatible.[44]

Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Human Rights

At the time of writing, the Parliamentary Joint Committee

on Human Rights has not reported on the Bill.

Key issues

and provisions

Schedule 1:

Australia-Israel Tax Convention

Section 3AAA of the ITAA 1953 lists the current tax

agreements covered by that Act. Item 1 amends section 3AAA(1) to include

the ‘Israeli Convention’ so as to implement the treaty, thus giving it the

force of law.

As discussed above and noted in the Explanatory

Memorandum, the A-I Tax Convention broadly follows the OECD’s Model

Tax Convention on Income and on Capital,[45]

and incorporates over 2,000 pages of technical and complex supporting

materials. The Explanatory Memorandum provides a good high level explanation of

the A-I Tax Convention and each of the articles, as does the National

Interest Analysis document prepared by the Treasury.[46]

It should also be noted that the A-I Tax Convention has been subject to

significant consultation and review, including a Treasury consultation process[47]

and review by JSCOT.[48]

In light of this, the Digest does not examine each of the

Articles in detail. Rather the Digest draws attention to some of the key

features of the A-I Tax Convention, specifically:

- the scope of the treaty, including taxes covered, taxpayers

subject to the A-I Tax Convention and the definitions of Australia and

Israel

- the modifications to withholding tax rates on dividends, interest

and royalty payments

-

a summary of the OECD’s BEPS measures adopted in the A-I Tax

Convention

- new exchange of information rules and

- specific rules relating to anti-discrimination and arbitration.

Each of these are discussed in more detail below.

Scope of the

A-I Tax Convention

Articles 1, 2 and 3 of the A-I Tax Convention

outline its scope. Specifically, Article 1 details the persons covered, Article

2 the taxes covered and Article 3 contains a definition of Australia

and Israel for the purposes of the A-I Tax Convention.

Person covered

Article 1 provides that the A-I Tax Convention

applies to persons who are residents of Australia and/or Israel (referred to in

the A-I Tax Convention as the Contracting States). Article 3

states that the term person includes an individual, company and any

other body of persons.

Article 1, paragraph 2 contains a specific rule

relating to the recognition of income derived through a fiscally transparent

arrangement or entity (for example income derived from a partnership or trust

distribution).[49]

In this situation, Article 1, paragraph 2 provides that for the purposes

of the A-I Tax Convention, that income will be deemed to be income of the

person to the extent that tax laws of Israel or Australia recognise that income

as being derived by that person.

Article 4 contains specific rules as to when a

person will be a resident of Australia or Israel for the purposes of the A-I

Tax Convention. These rules do not substantively differ from the OECD

model,[50]

and are well explained at pages 12 to 14 of the Explanatory Memorandum to the

Bill.

Taxes covered

Article 2 of the A-I Tax Convention stipulates

that the following taxes are covered:

- Israel taxes covered include:

- income

and company tax (including capital gains tax)

- taxes

on gains from the alienation of property according to Israel’s Real Estate

Taxation Law and

- taxes

imposed under Israel’s Petroleum Profits Taxation Law.

- Australian taxes covered include the following taxes imposed

under the federal law of Australia:

- Australian

income tax

- resource

rent taxes and

- fringe

benefits tax.

As such, Australian state taxes such as payroll tax and

stamp duties, as well as state-based mining royalties are not covered under the

A-I Tax Convention.

Definition of Australia and Israel

Article 3 of the A-I Tax Convention contains

a definition of what is meant by the terms ‘Australia’ and ‘Israel’. This is an

important element of the treaty, as the treaty amongst other things applies to

persons of Australia and Israel.

Article 3, sub-paragraph (1)(a) defines Israel as

meaning:

... the State of Israel and when used in a geographical sense

includes its territorial sea, as well as those maritime areas adjacent to the

outer limit of the territorial sea, including seabed and subsoil thereof over

which the State of Israel, under the laws of the State of Israel and in

accordance with international law, exercises its sovereign or other rights and

jurisdiction.

As noted at paragraph 1.38 of the Explanatory Memorandum:

Australia’s implementation of the Convention is without

prejudice to Australia’s support for a two-state solution to the conflict

between Israel and the Palestinians, including the resolution of final status issues.

For the purposes of the Convention, Australia interprets references to ‘the

State of Israel’ in accordance with Australia’s obligations under international

law and UN Security Council resolutions. Nothing in Australia’s implementation implies

recognition by Australia of any claims to disputed territories.

Article 3, sub-paragraph (1)(b) adopts the

following definition of Australia:

... the term "Australia", when used in a geographical

sense, excludes all external territories other than:

- the Territory of Norfolk Island;

-

the Territory of Christmas Island;

- the Territory of Cocos (Keeling) Islands;

-

the Territory of Ashmore and Cartier Islands;

-

the Territory of Heard Island and McDonald Islands; and

- the Coral Sea Islands Territory,

and includes any area adjacent to the territorial limits of

Australia (including the Territories specified in this subparagraph) in respect

of which there is for the time being in force, consistently with international

law, a law of Australia dealing with the exploration for or exploitation of any

of the natural resources of the exclusive economic zone or the seabed and

subsoil of the continental shelf.

New

withholding tax rates

Generally, where an Australian resident makes a payment of

a dividend, interest or royalty to a non-resident, withholding tax will be

imposed on that transaction. The withholding tax is payable by the entity or

person making that payment and will be imposed at a rate of ten per cent on

interest payments and 30 per cent on dividend or royalty payments unless varied

by Australia’s DTA’s.[51]

Articles 10, 11 and 12 have the effect of modifying

the rates of withholding taxes imposed on payments of dividends, interest and

royalties between residents of Australia and Israel. The effect of these

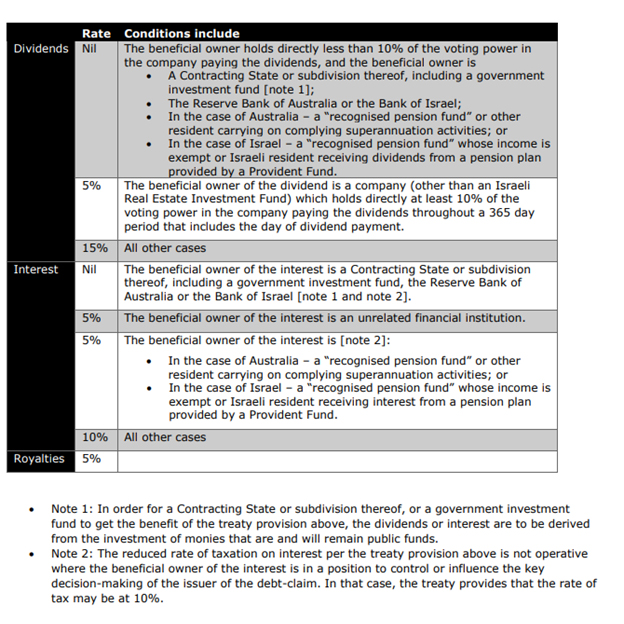

Articles is summarised by Deloitte and replicated in Table 1.

Table 1: summary of withholding tax rates under the A-I Tax Convention

Source: Deloitte Australia, Tax

insights – Australia and Israel: double tax treaty, 11 April 2019.

OECD BEPS Recommendations

As part of Australia’s commitment to addressing

multinational tax avoidance, the A-I Tax Convention adopts a number of

the OECD’s recommendations for addressing BEPS. The specific Articles giving

effect to, or incorporating the OECD’s BEPS recommendations are captured at

paragraph 1.11 of the Explanatory Memorandum of the Bill, and replicated below in

Table 2.

Table 2: summary

of BEPS recommendations incorporated into the A-I Tax Convention

| Australia-Israel

Tax Convention provisions |

BEPS

Project 2015

Final Reports |

| Title |

Action 6 |

| Preamble |

Action 6 |

| Article 1 (Persons covered),

paragraph 2 |

Action 2 |

| Article 5 (Permanent

establishment), paragraphs 5, 6, 7, 9, 10 and subparagraph 8(a) |

Action 7 |

| Article 7 (Business profits),

paragraph 9 |

Action 14 |

| Article 9 (Associated

enterprises), paragraph 4 |

Action 14 |

| Article 10 (Dividends),

subparagraph 2(a) |

Action 6 |

| Article 13 (Alienation of

property), paragraph 2 |

Action 6 |

| Article 22 (Limitation on

Benefits) |

Action 6 |

| Article 25 (Mutual agreement

procedures), paragraphs 1, 2 and 3 |

Action 14 |

Source: Explanatory

Memorandum, Treasury Laws Amendment (International Tax Agreements) Bill

2019, p. 6.

In response to a question on notice, the Treasury provided

JSCOT with a table outlining how the A‑I Tax Convention

incorporates the OECD BEPS Action Items. For completeness, this has been

replicated below in Table 3.

Table 3: summary

of specific BEPS recommendations incorporated into the A-I Tax Convention

|

Relevant

Article of the Australia-Israel tax treaty

|

OECD Action

Item

|

|

Title and Preamble

The express purpose of the treaty is to eliminate double

taxation with respect to taxes on income without creating opportunities for

non-taxation or reduced taxation through tax evasion or avoidance (including

through treaty-shopping arrangements).

|

This gives effect to an OECD/G20 Base Erosion and

Profiting Shifting (BEPS) Action 6 recommendation (Preventing

the Granting of Treaty Benefits in Inappropriate Circumstances).

It clarifies the object and purpose of the treaty also

includes avoiding opportunities for non-taxation or reduced taxation through

tax evasion or avoidance

|

|

Persons covered (Article 1)

Treaty benefits will be available for income derived by

or through fiscally transparent entities or arrangements (such as

partnerships and trusts) but only to the extent that the income is treated as

the income of one of the country’s residents under that country’s domestic

law.

|

This gives effect to a BEPS Action 2 recommendation

(Neutralising the Effects of Hybrid Mismatch Arrangements). It will

ensure that such income is not subject to double taxation, without granting

treaty benefits in inappropriate circumstances (such as where neither country

treats the income as belonging to one of its residents under its domestic

law).

|

|

Permanent

establishment (PE) (Article 5)

A PE will be deemed to exist in respect of the following

activities:

- A building site or construction project, that lasts for more

than 9 months; or carrying out of the related supervisory or consultancy

activities that exceeds 183 days or more in any 12 month period.

- Natural resource activities (including the operation of

substantial equipment) that exceeds 90 days or more in any 12 month period.

- Certain preparatory or auxiliary activities, such as

warehousing or purchasing goods, are excluded from the definition of PE.

- Integrity provisions will be included to prevent related

parties from circumventing the above PE time thresholds by splitting

contracts, or from fragmenting their preparatory or auxiliary activities to

avoid having a PE.

A PE will also be deemed to exist where a person (agent)

acts on behalf an enterprise, unless that agent is acting in a truly

independent capacity. This will ensure that the activities of dependent

agents of foreign enterprises fall within the definition of a PE.

|

Collectively, these integrity rules give effect to BEPS

Action 7 recommendations (Preventing the Artificial Avoidance of PE

Status) and will help guard against abusive arrangements intended to

circumvent the PE definition. The existence of a PE in a country enables that

country to tax local business profits derived by that PE.

|

|

Business profits (Article 7)

Transfer pricing adjustments are generally limited to

seven years. This time limit does not apply on a finding of fraud, gross

negligence or wilful default, or where an audit has commenced in relation to

the profits of the enterprise within a period of 10 years

|

This gives effect to an OECD BEPS Action 14

recommendation (Making Dispute Resolution Mechanisms More Effective).

It will help prevent late adjustments to provide greater taxpayer certainty.

|

|

Associated enterprises (Article 9)

Where one country adjusts the taxable income of a

resident enterprise to reflect the arm’s-length conditions of a transaction

with an associated enterprise, the other country will be required to make a

correlative adjustment. Time limits apply for the commencement of transfer

pricing adjustments

|

This gives effect to an OECD BEPS Action 14

recommendation (Making Dispute Resolution Mechanisms More Effective).

It will help prevent late adjustments to provide greater taxpayer certainty.

|

|

Dividends (Article 10)

The source (of the dividend) country may tax outbound

dividends up to the following limits:

- Zero - for dividends derived by governments (including

government investment funds), central banks, tax exempt pension funds or

Australian residents carrying out complying superannuation activities on

direct holdings of no more than 10 per cent;

- 5% - of the gross amount of the dividend for intercorporate

dividends paid to companies that hold 10 per cent or more of the paying

company throughout a 365 day period;

- 15% - in all other cases.

|

The 365-day holding period requirement for dividends

attracting the 5 per cent rate gives effect to an OECD BEPS Action 6

recommendation (Preventing the Granting of Treaty Benefits in

Inappropriate Circumstances).

It will help guard against potential abuse cases where a

company with a holding of less than the specified holding percentage

increases its holding shortly before the dividends are paid for the purpose

of securing the benefits of the provision.

|

|

Alienation of property (Article 13)

Income, profits or gains from the disposal of immovable

property (such as land) or of shares or comparable interests in land-rich

entities may be taxed in the country where the property is situated (as a

primary taxing right), and a secondary taxing right is provided to the

alienator’s country of residence.

An integrity rule will ensure that the rule for

land-rich entities will apply if the relevant conditions are met at any time

during the 365 days preceding the disposal. Income, profits or gains from the

disposal of PE assets may be taxed in the country where the PE is located, as

well as in the country where the enterprise is resident.

Income, profits or gains from the disposal of ships or

aircraft operated in international traffic, as well as from the disposal of

other assets pertaining to those operations, will be taxable only in the

country of residence of the operator.

Residual capital gains may be taxed in the country the

country where the alienator is a resident, as well as in the country where the

property is located (if the alienator is not the beneficial owner).

|

The 365-day integrity rule gives effect to an OECD BEPS

Action 6 recommendation (Preventing the Granting of Treaty Benefits in

Inappropriate Circumstances).

It will help guard against potential abuse cases where

a company alters its asset mix prior to disposal to ensure it is not land

rich on the date of disposal.

|

|

Limitation on benefits (Article 22)

The treaty includes a rule denying treaty benefits, in

certain circumstances, if a principle purpose of an arrangement or

transaction is to a treaty benefit.

|

This gives effect to an OECD BEPS Action 6

recommendation (Preventing the Granting of Treaty Benefits in

Inappropriate Circumstances).

This ensures that the treaty should apply in accordance

with the purposes for which it was entered into, that is, to provide benefits

in respect of bona fide exchanges of goods and services and movements of

capital and persons, as opposed to arrangements whose principal objective is

to secure a more favourable tax treatment.

|

|

Mutual agreement procedure (MAP) (Article 25)

Taxpayers will have three years in which to seek the

revenue authorities’ assistance in the resolution of tax disputes arising

from the application of the treaty. Protocol paragraph 12 establishes a

competent authority notification process, to ensure that the competent

authorities of Australia and Israel are made aware of MAP requests that are

submitted and, therefore, are able to give their views on whether the request

is accepted or rejected, and whether the person’s objection is considered to

be justified.

|

This gives effect to an OECD BEPS Action 14

recommendation (Making Dispute Resolution Mechanisms More Effective)

and ensures the efficient operation of the MAP dispute resolution mechanism

for taxpayers.

|

Source: Treasury, Submission

to JSCOT, Inquiry into the Convention between the Government of Australia

and the Government of the State of Israel for the Elimination of Double

Taxation with respect to Taxes on Income and the Prevention of Tax Evasion and

Avoidance, [Submission no. 1], 19 September 2019.

Exchange of

information

Article 26 of the A-I Tax Convention sets

out rules and procedures for the exchange of information between the Australian

Taxation Office (ATO) and Israeli Ministry of Finance. Article 26, paragraph

1 stipulates that information may be exchanged to the extent that it is

foreseeably relevant for carrying out the provision of the A-I Tax Convention

or enforcement of domestic laws covered by the A-I Tax Convention. This

is a departure from the OECD Model Tax Convention, which allows information

relating to any taxes to be exchanged.[52]

Other points to note include:

- the exchange of information is not limited to residents of

Australia or Israel – that is, information about non-residents can be exchanged[53]

- any information exchanged under the Article will be afforded the

same level of secrecy as if that information was obtained in the other country

– that is, Australia’s taxpayer secrecy provisions will apply to information obtained

from Israel under Article 26[54]

- information cannot be exchanged where the relevant tax authority

would not be able to obtain that information under their domestic laws.

Similarly, information cannot be exchanged where its supply would disclose any

trade, business, industrial, commercial or professional secret or trade

process, or the disclosure would be contrary to public policy. [55]

Anti-discrimination

and arbitration rules

Articles 24 and 25 of the A-I Tax Convention

contain non-discrimination rules and mutual agreement procedures. Broadly:

- Article 24 provides that under the A-I Tax Convention

nationals of Australia and Israel cannot be treated less favourably than

nationals of the other country in the same circumstances. This

non-discrimination rule is also extended to permanent establishments.[56]

However, unlike the OECD Model Tax Convention, Article 24 does not

extend these non-discrimination rules to residents of third countries.[57]

- Article 25 provides a mechanism for resolving taxpayer

disputes or resolving difficulties arising from the application of the A-I Tax

Convention. This is achieved through a mutual agreement procedure (MAP)

whereby Australian and Israeli tax authorities are required to endeavour to

resolve the dispute. Importantly, taxpayers will have three years in which to

bring a complaint under a MAP process. More information about MAP can be found

on the

ATO website.[58]

What rules

or laws are not impacted by the A-I Tax Convention?

As noted in the Article 1 of the Protocol to the A-I Tax

Convention, the following domestic rules are outside the scope of the A-I

Tax Convention:

- measures

designed to address thin capitalisation and dividend stripping

- measures

designed to address transfer pricing

- controlled

foreign company and transferor trust rules

- measures to ensure that taxes can be effectively collected and

recovered, including conservancy measures

- foreign

occupational company rules and

- general

anti-avoidance rules.

Further, the A-I Tax Convention does not include an

Article requiring the other country to provide assistance in collecting taxes.

As noted by Deloitte, only six of Australia’s 45 treaties include such a

provision, and it is not usual practice for Israel to include such an Article.[59]

Schedule 2:

The new deemed source rule

Schedule 2 of the Bill inserts a new Division 764

into the ITAA 1997. Specifically, proposed subsection

764-5(1) of the ITAA 1997 provides that income, profits or gains

will have a source in Australia if, for the purpose of an international tax

agreement, the income, profits or gains of a foreign resident are taxable in

Australia under the terms of that tax agreement.

Therefore, the effect of this is that the new deemed

source rule will treat income, gains or profits as being sourced in Australia

where an international tax agreement allocates Australia a right to tax that

income, gain or profit in respect of a resident of a foreign country or

territory for the purposes of that international tax agreement.[60]

Proposed subsection 764-5(2) of the ITAA 1997

stipulates that proposed subsection 764-5(1) of the ITAA 1997 will

apply to international tax agreements made on or after 28 March 2019.