Papers on Parliament No. 55

February 2011

Prev | Contents | Next

What a great thrill it is to return to Australia, where I came to live in 1990 for almost five years, while my husband had a posting to the US Embassy. And it’s a thrill to return to Canberra, where I had the honour and the privilege of being the only accredited US reporter to work in the Parliamentary Press Gallery at that time.

During my years of wandering these hallowed halls of government and power, I wrote almost 500 articles for various US publications and I also served in the press pool during the visit of Queen Elizabeth II and US Secretary of State Warren Christopher, and other US, Australian and international dignitaries. I was also standing in this very building, on the steps of the Great Hall, when the first President Bush arrived for a state visit, only days after former Prime Minister Bob Hawke had moved aside and Paul Keating became the new prime minister. What an amazing sight it was to see US flags flying over your Parliament as a gesture of welcome.

This visit galvanised for me the importance of ‘nuance’ in words, drawings and body language, which I will talk about shortly in the form of political cartooning. But it quickly acquainted me with the fact that US and Australian words—and gestures—can mean very, very different things. And sometimes generate unintended interpretations and embarrassing results.

In 1991, at a lovely lunch the Australian Government hosted for the visiting President Bush, I was sitting at a table of young and enthusiastic Republican aides who were amazed to hear Canberra described as ‘the bush capital’. One US staffer promptly noted: ‘I had no idea they loved our president!’ A State Department aide quietly pointed out that ‘bush’ in Australia meant the ‘the outback’ and had nothing to do with politics. The US fellow turned bright red.

Unfortunately, in all the briefings Bush had received for the trip, no one had thought to say to the president: these gestures and words are not appropriate. Do NOT use them! So there he was, in the midst of angry farmers, upset over some protective US agricultural legislation, waving his hands in front of your parliament, in what he thought was the ‘V for Victory’ sign—instead of a very negative admonition! Like all campaigning politicians, Bush was eager to get out there and shake hands with the crowds. One eager bystander caught the US president totally off guard when she thrust a squirming infant into his arms and said, ‘Would you like to nurse this baby?’ Well, since no one had bothered to tell him the Australian meaning for that word, Bush presumed she meant the biological function and he sheepishly replied: ‘I may be the President of the United States, but I know my limits!’

You did not see this story in the US papers—or in a Pryor cartoon!

You may remember this trip, since it had not gotten off to a good start. President Bush (the first) was about to kick off his re-election campaign, and to show how ‘fit’ he was, aides insisted he get out jogging as soon as his plane landed in Sydney, in spite of his age and the gruelling flight. I was part of the CNN pool coverage for this visit. As you may remember, later on, there he was, on international TV, when CNN first announced he had died, because of garbled reports that ‘he had taken ill’. And if you could die from pure embarrassment, he surely would have, after throwing up on the Japanese prime minister, while the TV cameras were rolling with an international feed. Not the best diplomatic move!

Such are the follies and foibles of men and nations! Their actions do not go unnoticed by an ever vigilant press.

As a long-time journalist, I have always believed that ‘the pen is mightier than the sword’. And, as a writer, I also subscribe to the cliché that ‘a picture is worth a thousand words’. Nowhere is this more true than when that pen is in the skilful hands of a political cartoonist, who uses a deft stroke to level tyrants, to puncture the pompous, to reflect on aspects of humanity, to question social norms (or the lack thereof) and to create needed humour and comic relief in viewing the weaknesses and quirks of nations and men. Besides the artistic vision and drafting skills needed to generate an instant impact, the political cartoonist must also have a grasp of human psychology, history and geography, world events and perspective. Often, the drawing is not to make people laugh, but to force them to confront moral issues that others seek to avoid or to force a re-thinking on aspects of the status quo.

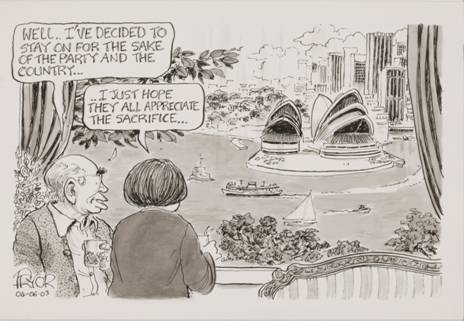

Cartoonists are a rare breed of observers, and one of the most skilful at this craft has been Geoff Pryor, who was the cartoonist at the Canberra Times for 30 years, from 1978 to 2008. There were no ‘sacred cows’ that escaped his powerful pen as he focused on politicians and the public alike, both in Canberra and across the world. In 2004, he won the People’s Choice Award, sponsored by the National Museum of Australia’s ‘Behind the Lines’ exhibit. He beat out 65 fellow cartoonists for the prize. Pryor’s winning entry, ‘The Decision’, was in response to John Howard’s announcement to continue as Liberal Party leader, and shows the prime minister in his Sydney home, Kirribilli.

Geoff Pryor, Canberra Times, 4 June 2003

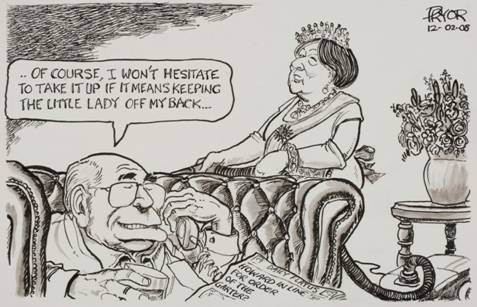

Another signature cartoon shows Howard after being nominated for the Order of the Garter.

Geoff Pryor, Canberra Times, 12 February 2008

A retrospective exhibit of Pryor’s three decades of work opened on 29 November 2008, at the National Museum of Australia in Canberra and ran through to 12 February 2009. Described in the exhibit as an ‘astute observer and commentator’ on the world around him, ‘Pryor carefully dissected and exposed the motivations of Australia’s politicians. All of his work, to the last cartoon, was produced via simple pen and ink rendering—an increasingly rare skill in the new era of born digital cartoons’, according to the show’s promotional brochure[1]. But leaders around the world were also fair game for his stiletto pen, including dictator Idi Amin of Uganda, the Shah of Iran, and the Pope. He also focused with laser-like precision on many US presidents, from Nixon to George Bush II. He loved skewering US politicians as much as he did Australian ones.

He was always looking for overlapping themes on the world stage, including the military, global environmental issues, immigration, racism, government spending and tax payer money, greed, hypocrisy, religion, morality, and the universality of human foibles.

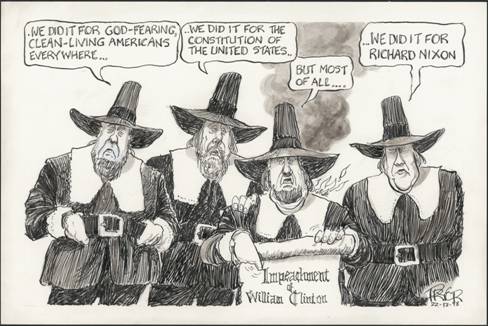

Geoff Pryor, Canberra Times, 22 December 1998, nla.pic-vn4699031,

National Library of Australia

While Pryor could be very entertaining, his goal was to be provocative, to strip off the façade of respectability, and to dig into the questionable core. One of his US-related works that I still vividly remember was sketched during the congressional impeachment trial for Bill Clinton in 1998, and the drawing compared it to the political climate of the Salem (Massachusetts) witch trials back in the 17th century.

In looking at Pryor’s cartoons, I need to remind myself that some US audiences still have strong ties to the Puritan culture, and many of Pryor’s works would never have made it into print in our country. This is aside from the fact that we readily proclaim our First Amendment right to free speech. But there are also questions of ‘taste’ and ‘shock value’ and ‘ethnic sensitivities’. I will talk about those later.

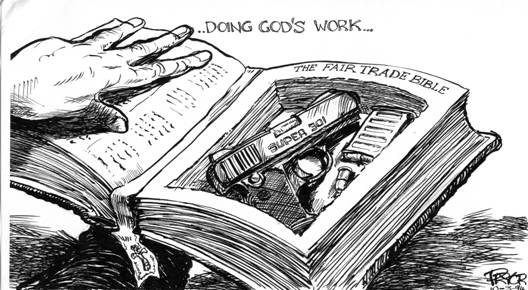

Pryor had no qualms lampooning American politicians and practices, with bullseye skill. He tackled the wars that Americans and Australians fought in jointly, from Vietnam to Afghanistan and Iraq. And while mindful of the Aussie mantra that ‘We fought shoulder to shoulder with the USA in every war’, Pryor was quick to point out that that wasn’t the case for the Trade Wars, where American agricultural protectionism undercut Australian markets. He took a hard look at the catastrophic attacks of September 11, 2001, in New York City, Pennsylvania, and Washington, DC, and examined the worldwide ripples it created. His drawing board tackled questions in both the US and Australia of the US Government’s new uses of powers of detention, secrecy, torture, and rendition versus privacy, personal freedom, and transparency.

Pryor hit a nerve where he zeroed in on controversies of immigration and asylum, race, and guns, with wide reverberations. One of the most powerful directed against the USA was the ‘Fair Trade Bible’ with a handgun tucked inside the pages of that book.

Geoff Pryor, Canberra Times, 10 March 1994

Love him or hate him, Pryor proved to be a national icon. He evoked strong national sentiments, depending on the viewer’s perspective on controversial issues. He was always a hot topic at the breakfast table or at the bar after work. While he often focused on strictly domestic issues in Australia, he never lost the international perspective, with the world as his drawing board. And my hope is that some day he will be honoured with a show in Washington, DC, just like his Australian countryman, cartoonist and sculptor, Pat Oliphant, has had. I thought he had gotten close. Just before I left on this trip, I was speaking to the Australian Ambassador to the US, Kim Beazley, during a story interview. He misunderstood my question because of a bad phone connection and launched into a discussion of an upcoming embassy show on Geoff Pryor. But his cultural aide called back to correct this mistake and said it was ‘Greg Pryor’, an artist from Western Australia with whom I am not familiar, and not Geoff Pryor, who was slated for this upcoming exhibit. This is how rumours get started!

In examining the vital role of cartooning in modern life, Australian ABC commentator Phillip Adams[2] once noted that

Australia produces so many good cartoonists. So many, that you’d swear our political life existed to mimic their cartoons. For, as the days pass, I have the strange feeling that their art precedes rather than imitates life. That they are not descriptive but predictive.

He further adds that

their skills are, by order of magnitude, greater than ours [as writers] and infinitely more important than the anonymous huffings and puffings of editorial writers. I may say that through clenched teeth, but it must be said.

In his remarks, Adams compares cartoonists to seismologists who chart the shifts under the earth’s surface and the responses of the onlookers:

The cartoonists have their ears to the ground, ready to amplify every tremor, right up to and including the major upheavals ... Not content with mere reactions, or with simple calibration, the cartoonists are duty-bound to exaggerate the scale of conflict—in the hope of alerting us to an untoward event or preposterous utterance. Okay, I’m straining for metaphors—so do cartoonists. But if Richter and his scale are too distant from human events, then perhaps I should equate cartooning with lie detection.

In their work, ‘Two Men and Some Boats: The Cartoonists in 200l’,[3] researchers Haydon Madding and Robert Phiddian reviewed 350 Australian cartoons that ran during that election year. In assessing the variety of interpretations and topics covered by the cartoonists’ work, the two observed that Australian

cartoonists do not consistently fit into the ‘elites’ category derided by [John] Howard; their hostility towards the business of politics, policy making and political correctness makes them unreliable members of the chattering classes. Many of them cherish their status as voicing the little bloke’s view on the editorial page and they are as cynical as the best of them.

But one issue where the artists were galvanised was on ethical and moral questions surrounding the asylum debate, following the drowning of 350 refugees off the Australian coast near Java. ‘Surely, the cartoonists thought, this was enough to humanise the refugees and make Australians feel the issue with greater sympathy’.

![Geoff Pryor, ‘We’d love to mate, but we’re choc-a block’, [2001]](/binaries/senate/pubs/pops/pop55/c03_clip_image002_0003.jpg)

Geoff Pryor, ‘We’d love to mate, but we’re choc-a block’, [2001]

Added Manning and Phiddian,

On this issue, however, they [the cartoonists] took a moral stand. It could not be written off as a ‘conspiracy of class traitors’ in the liberal broadsheets, either, because cartoons ran just as strongly outside Sydney, Melbourne and Canberra and in the tabloids as well.

Another triggering event was the terrorists’ attacks in the United States on September 11, 2001, and the impact they had not only on the United States but also on Australia as well. In tandem with the asylum issue, ‘the other essential component of the xenophobic hysteria was the war against terrorism and Australia’s rallying in exuberant loyalty to the US’.

Researchers Manning and Phiddian wrote that ‘Australian newspaper cartoonists worked in the shadow of 11 September and the “war against terrorism”. It was a dark shadow’, the two stressed.

In the last couple of [Australian] elections we have argued that cartoonists have become increasingly disgusted by and disengaged from the process. We must tell a different story for 2001: cartoonists were more disgusted than ever by electioneering but they were certainly not disengaged. The issues that inspired them were the moral question of how we should treat asylum seekers who arrive in boats and the sense that the war in Afghanistan (viscerally, if not entirely logically, connected to it) was being exploited for political purposes. This anger tended to wash over into their coverage of other issues, leading to a cartoonists’ campaign marked by plenty of satirical darkness and little comic relief.

The authors criticised the cartoonists for this shift into emotion. ‘They were more unfair and powerful than in any campaign we have yet covered’, Manning and Phiddian stated.

Pryor jumped into the fray.

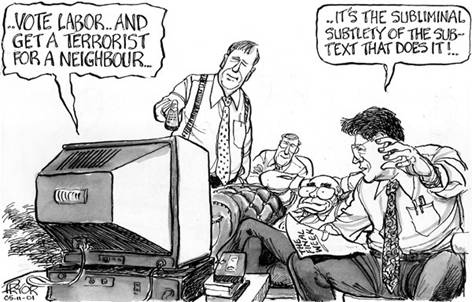

His cartoon (of 5 November 2001) is titled ‘Subtlety’, and shows John Howard and campaign staff listening to an unseen television voice which says, ‘Vote Labor ... and get a terrorist for a neighbour’. An adviser chimes in: ‘It’s the subliminal subtlety of the subtext that does it!’

Geoff Pryor, Canberra Times, 5 November 2001

In another cartoon, from 8 November 2001, Pryor is described by Manning and Phiddian as highlighting ‘the amorality of retiring [Peter] Reith’, the Liberals’ treasurer, Peter Costello, and a cartoon reference to the ‘asylum seekers fiasco’.

Geoff Pryor, Canberra Times, 8 November 2001

Writer Malcolm McGregor of the Australian was cited by the two researchers for his comment that

When federal Liberal MP Julie Bishop and Labor candidate Peter Knott cannot say what at least a significant minority of Australians think about refugees and terrorism—the two most visceral, totemic issues of this campaign—there is something seriously wrong with our electoral system.

Cartoonists did not share that silence:

This was the conclusion of the cartoonists in their focus on the sanctimonious, hypocritical and mean-spirited treatment of boat people by our political leaders and the sickening discipline that showed in beating the drum or playing the race card.

Manning and Phiddian, commenting on the strong tone of cartoons in the last week of the 2001 Australian election campaign, added:

Other forms of political analysis might wish to insist on a more nuanced summary of the issues, but the cartoonists went for force rather than subtlety just about every time. They tried to tell the public that the darker angels of our nature were being played on by cynical, poll-driven politicians. They tried to get Australians to recognise the morally decent view on asylum seekers and to think other than jingoistically about the war on terrorism. We did not listen.

But throughout his life, Pryor is someone who did listen—to a wide gamut of influences, and he looked at, questioned and wondered why things were the way they were. From childhood on, he had lots of curiosity and chutzpah, signing his own absence notes when he missed classes in school. Born in Canberra in 1944, his father (a surveyor, engineer and draftsman) was the city’s superintendent of Parks and Gardens, a science researcher, and an adept watercolourist. His mother, who was the first woman to start and finish a university degree in Canberra, he described as ‘a great reader [and] frustrated writer’[4] who worked for a South Australian parliamentarian. Both his grandfathers were good draftsmen, one a freelance cartoonist who often listened to political debates on the radio.

‘From the earliest days, I was interested in drawing. I was a diligent doodler on just about anything that had a white space’, said Pryor. He won his first prize, at age six or seven, for a competition held by the Farmer’s department store in Sydney. ‘I even drew on the desk top at school and got into all sorts of trouble’. But it was years before he began cartooning as a serious pursuit, and he never had any formal study of art.

He went to the Australian National University (ANU) to study law—‘the parents didn’t see much future in art for anybody, let alone myself’, but he did caricatures of the faculty and staff and got commissions from the Economics and Law school faculties. And then he published his first cartoon strip. But halfway through ANU, he dropped out of school in 1965 and held a series of jobs, including work as a labourer, weighing sugar at a grocery store, driving a taxi, working ‘as a go-for’ in the public service, and photo retouching and press art for the Canberra Times. He saved his money so he could go overseas. He took a ship to Panama, then flew to Miami, visited his brother living in Indiana in the United States, and then headed to Toronto, Canada, in 1969. ‘It was easy to find work—no language difficulties—and it was a good launching pad for travelling further afield’, Pryor said.

He got a job with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) and first worked in accounting and then moved to production, and then to videotaping. He was also studying television production, and eventually found a job at a studio—that lasted two days. ‘But during that stage, I kept up with the drawing and I did caricatures and drawings for people, sometimes on commission’, including the CBC newsletter, which went throughout the country. He also visited many Canadian art museums. In 1974, he went off with a friend to visit the Mediterranean and the Middle East, including Spain, North Africa, Sicily, Italy, Greece, and Turkey.

It was literally ‘on the road to Damascus’ that he decided it was time to get serious about the direction for his life, instead of the vagabond existence, and to pick up some formal training.

When the money ran out, Pryor decided to head for London and got a job at Asprey’s, the regal jewellers on Bond Street, in the packing room—wrapping up consignments of crystal and jewellery for distant destinations. He was still working on his drawings and visiting contacts on Fleet Street. On the job as a packer, he was also working his wicked sense of humour. Pryor popped in a note on a package for the Sultan of Oman, saying: ‘Help support the Israeli war effort’!

He moved back to Canada, getting a job as a rust-proofer for cars while looking for cartooning jobs. But he also kept his eye on the Canberra Times which was among the Australian papers on display at the Australian Trade Commission. One day he noticed their resident cartoonist Larry Pickering had left the paper (for the Australian) so he decided ‘I would go back to Canberra and become the cartoonist of the Canberra Times’.

The year 1975 was a turning point for Pryor. The death of his mother sent him back to Canberra, where he re-enrolled in ANU in an arts program. This time, he dove in, studying things like international relations, Marxism, African history, the world’s revolts and insurgencies. Pryor was also fascinated by courses in comparative religions. Having travelled through Muslim countries and encountering Islam, Pryor said, ‘I was curious to know how they ticked, how people, how they existed in their societies, how much of a role religion played and what it meant to them’. Outside the classroom, he began to freelance for the Canberra Times.

In 1978, he had another major sea change. At age 34, he got married and gained a wife and a son, bought a house, and officially joined the staff of the Canberra Times, where he remained until his retirement in February 2008.

He has never looked back.

As to his evolutionary process of being a cartoonist, he adds,

I can’t remember when, I couldn’t put my finger on it in terms of time, when I decided that I wasn’t going to be anybody else; [that] I was going to be me; and that I would draw the cartoons in a way that suited me to get the idea across. And then, over time, I began to develop a sense of political knowledge, political history, and my grasp of issues became much surer. I became much more competent about which issue was worth a cartoon comment, and which wasn’t.

He is quick to echo the comments of a British cartoonist who influenced him, who emphasised that ‘humour is a serious business. It’s not something that you fall about in a state of permanent laugher. It’s a serious business of creation’. It can also be a ‘daily strait-jacket’, with a demanding schedule. But it also provides a worldwide vehicle. Oral history interviewer Ann Turner (for the National Library of Australia collection) remarked to Pryor: ‘You’re drawing for a Canberra audience, but you seldom choose local themes. Is that deliberate?’ Pryor responded with an emphatic ‘Yes!’:

You have to cast the net as wide as reasonably possible because we are in this business for survival, if nothing else. We have to keep going from day to day. You’ve got to be able to deepen and broaden your bag of reference material. Using local references constantly would be self-defeating, because I think the readership of Canberra is, by and large, highly educated. They’re not parochial. They’re cosmopolitan, so you can often refer to foreign parts as sources of metaphor and assume that the readers will know. You can refer to historical incidents ... and assume your readers will know.

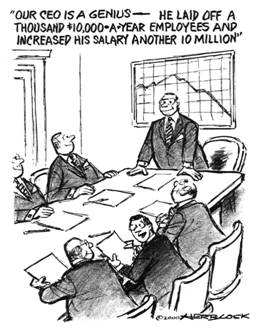

I would like to say a few words about political cartooning in the USA, by way of contrast, with the styles, techniques and topics. Probably the most well known would be Herb Block, whose pen name was ‘Herblock’. His career began in 1929 with drawings of President Herbert Hoover and ended in 2001 under President George W. Bush. He spent 55 years at the Washington Post, from 1946 to 2001, winning three Pulitzer prizes. This year, the US Library of Congress honoured him with an extensive exhibit, with works selected from the more than 14 000 pieces on file. The things he focused on decades ago—unemployment, racial tensions, energy policy and over-compensated executives—are still timely issues today in the United States.

|

|

|

|

‘Don’t look now but he’s still standing there’, 1936 Herblock cartoon, copyright by The Herb Block Foundation

|

‘Race’, 1968 Herblock cartoon, copyright by The Herb Block Foundation

|

|

|

|

|

‘Hostage’, 1979 Herblock cartoon, copyright by The Herb Block Foundation

|

‘Our CEO is a genius—He laid off a thousand $10,000-a-year employees and increased his salary another 10 million’, 2000 Herblock Cartoon, copyright by The Herb Block Foundation

|

Regardless of country of origin, Herblock seemed to set out the criteria that most top-notch cartoonists follow: ‘A cartoon does not tell everything about a subject. It’s not supposed to. No written piece tells everything either. As far as words are concerned, there is no safety in numbers. The test of a written or drawn commentary is whether it gets at an essential truth’, he said.[5]

Herblock’s successor in 2002 was Tom Toles. He tends to focus more on US issues than international ones. In a country with 300 million people, there are plenty of volatile topics to choose from.

‘Gay wedding cake’, Toles © 2009 The Washington Post.

Reprinted with permission of Universal Uclick. All rights reserved.

In the United States, we have seen a severe economic consolidation of media, especially for print, and this has hurt political cartoonists. Randy Barrett, a reporter for the National Journal, estimated there are now only 80 full-time cartoonists at leading metropolitan dailies—down from about 200 only 20 years ago. About 85 per cent are older white males, who earn an estimated US$50 000 to $75 000 a year. He notes that cartoonists, like reporters, guard their autonomy fiercely. While working for the now defunct Buffalo Courier-Express, Tom Toles ‘won the right to lampoon anybody and everybody ... and he insisted on full creative control when he joined The Washington Post in 2002’. Added Toles, ‘Once you have [editorial freedom], it’s so important and intrinsic it’s inconceivable to work without it’.[6]

But having independence does not mean that all cartoons get published. Rather than raising the issue of censorship, it can be a question of taste, sensitivities, raw emotions or being perceived as too offensive to various segments of the audience. In 2004, editors vetoed a cartoon by Jeff Danziger for the New York Times Syndicate showing President George W. Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney paddling an American GI’s corpse down a river, during the Iraqi and Afghani wars.

Jeff Danziger, ‘Stay the course’, 2004.

Reprinted with permission of Cartoonists & Writers Syndicate

Rob Rogers, president of the American Association of Editorial Cartoonists and a staff cartoonist for the Pittsburg Post-Gazette, had his drawing rejected of Osama Bin Laden inside a Catholic church during the wide-ranging child molestation scandal involving Catholic priests throughout the United States.

Copyright 2003 Rob Rogers. Reprinted with permission

Pryor also had some drawings pulled. Both dealt with depictions during the 1998 impeachment furore over President Bill Clinton. One showed Palestinian Liberation Organisation leader Yassar Arafat, in Washington for Middle East peace talks, but kept waiting while Clinton was sidetracked by US reporters, wanting to talk about the scandal involving a White House intern. A second one, which was described as censored, ‘for taste, not politically’, showed Clinton at the zoo as snake specialists warned him: ‘We’ve got a trouser snake on the loose!’

Question (Ian Matthews) — I am going to bask in Geoff Pryor’s fame because I appointed him. You mentioned about some cartoons not being published in the United States because of sensitivities, one of the things that differs in Australia is that our defamation laws are much stricter than yours. I hid behind Geoff Pryor a lot because you can’t call a politician a liar, but you can draw him with a Pinocchio nose and Geoff Pryor did this very well. My question really is, in what way do cartoonists defame people?

Kathleen M. Burns — I know that the Australian press law is very different from US media law. A case that comes to mind is that of Leo Schofield, the Sydney Morning Herald restaurant critic, who wrote that the food at some restaurants was terrible, and some people who ate there agreed. But the owner filed suit, and won. In the USA, we go back to 1793 with the beginnings of libel law, with the principle that: ‘truth is a defence’. It is traced to colonial printer John Peter Zenger and the Zenger Defence. If you can prove something is true, then it is not defamation. Today, I think it is tough to know who is a public and who is a private person. What is covered by privacy law? I am amazed we can get anybody to run for office in our country anymore, because if you had a third cousin that ran off at age 12, or there is anything ‘questionable’ that you have ever done, it is open to public scrutiny. In terms of defamation, I have seen some things in the Australian newspapers in the last two weeks that I thought were verging on defamation. It think it is interesting, too, with this particular election campaign, that the media would focus on the fact that someone did not have children (Julia Gillard) or somebody’s swimming gear (Tony Abbott) or their hair (Gillard) or their nose (Gillard) versus someone’s ears (Abbott) and skip things of substance, like the Afghan war, international trade or the state of the economy. I think Geoff Pryor would have done a whole lot more editorial comment with his cartoons if he was still involved in this election, versus what the local and national media have done.

In the United States, with more than 300 million people, you are bound to offend someone with every cartoon you draw, but it’s a long way from defamation. I am not a lawyer but when I worked at the Chicago Tribune and many other publications, everything goes to the lawyers for review—including cartoons. What is interesting is that Tom Toles of the Washington Post does four cartoons a day, and they are circulated among the editorial staff to see what will be published. It would be hard enough to create one a day!

[1] Geoff Pryor retrospective, National Museum of Australia, viewed August 2010, www.nma.gov.au/exhibitions/now_showing/the_hall_exhibitions/geoff_pryor_hall_retrospective/.

[2] Phillip Adams, ‘Introduction’, in Ann Turner (ed.), In Their Image: Contemporary Australian Cartoonists. Canberra, National Library of Australia, 2000, pp. 1, 4.

[3] Haydon Manning and Robert Phiddian, ‘Two Men and Some Boats: The Cartoonists in 2001’, in John Warhurst and Marian Simms (eds), 2001: The Centenary Election. St Lucia, Qld, University of Queensland Press, 2002, pp. 41–61.

[4] Quotes from Geoff Pryor in the remainder of this paper are from the transcript of oral history interview with Ann Turner, 1998, ORAL TRC 3671, National Library of Australia, pp. 3–4, 7, 15, 17–18, 22, 25–6, 29, 32, 37, 48–9.

[5] Herb Block, ‘The Cartoon’, Herblock’s History: Political Cartoons from the Crash to the Millennium, Library of Congress, viewed August 2010, www.loc.gov/rr/print/swann/herblock/cartoon.html.

[6] Randy Barrett, ‘Trying Times in Toontown’, National Journal, 2 July 2007, http://news.nationaljournal.com/articles/070207nj1.htm.

Prev | Contents | Next

Back to top