198 Objection to ruling

-

If an objection is taken to a ruling or decision of the President, such objection must be taken at once and in writing, and a motion moved that the Senate dissent from the President’s ruling.

-

Debate on that motion shall be adjourned to the next sitting day, unless the Senate decides on motion, without debate, that the question requires immediate determination.

Amendment history

Adopted: 19 August 1903 as SO 420 but renumbered as SO 415 for the first printed edition

Amended:

- 10 September 1909, J.126 (to take effect 1 October 1909) (clarification of mechanism for deciding that the question requires immediate determination)

- 26 November 1981, J.716–17 (deletion of reference to the motion for dissent being seconded)

1989 revision: Old SO 429 restructured as two paragraphs and renumbered as SO 198; expression streamlined and language modernised

Commentary

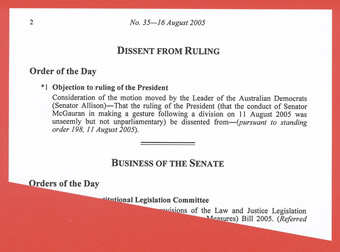

A motion of dissent from a ruling of the President is automatically adjourned till the next day of sitting unless a motion that it be resolved immediately is agreed to. The matter appears at the top of the Notice paper for the next sitting day

A ruling of the President has the force of an order of the Senate and is therefore binding on the Senate unless it is overturned by a decision of the Senate. This principle was established by the Senate’s first President, Sir Richard Baker, and reinforced by a ruling of President Gould in 1908.[1] SO 198 provides the mechanism for challenging a ruling of the President.

An objection to a ruling of the President must be:

-

in writing; and

-

taken at once.

A requirement for the motion of dissent to be seconded was removed in 1981, in line with the removal of such a requirement for all motions. For details, see commentary on SO 84.

In the form in which it was adopted in 1903, SO 198 did not specify how the Senate was to decide whether a motion of dissent required immediate determination. According to Edwards in the 1938 MS, it was left to the President to decide whether or not the matter should be adjourned till the next sitting day. Some difficulties were encountered and, at President Gould’s instigation, the Standing Orders Committee recommended that senators should determine the question. In its general review and clean-up in 1908, the Standing Orders Committee proposed three changes to the order. The first two were to specify that the Senate would decide “on motion, without debate” that the “question” (rather than “matter”) required immediate determination. These were straightforward changes and were agreed to virtually without debate.[2]

The third change, however, was controversial in that it sought to limit the total time for debate on a motion of dissent to one hour, with no individual senator speaking for more than 15 minutes without leave. The proposal was watered down in the course of debate to an individual time limit only. At a time when there were no general time limits on debate, Senators took umbrage at what looked like an attempt to stifle criticism, although the proposal was strongly supported by some, including the outspoken Scot, Senator Stewart (ALP, Qld) who quibbled with the proposition put forward by future President, Senator Givens, that senators may need more than 15 minutes in order to quote authorities:

Senator STEWART – There is no need to quote authorities. We are the authorities. This digging in the catacombs is only wasted effort. Let honourable senators get up and say how a matter appears to them to affect public business. We should not mind what was said by May or someone else who is dead and buried and forgotten.[3]

The proposal was defeated by 16 votes to 9.

See Odgers’ Australian Senate Practice, 12th edition, p.212 for precedents for adjourned motions of dissent. Such motions are placed at the top of the Notice Paper for the next day. This first occurred on 22 October 1909, shortly after the amended standing order took effect.