69 Presentation of petitions

-

A petition shall be lodged with the Clerk, at least 3 hours before the meeting of the Senate at which it is proposed to have it presented, and in order to be presented must bear the Clerk’s certificate that it is in conformity with the standing orders.

-

At the time provided the Clerk shall make an announcement that petitions have been lodged. At the commencement of the sitting a list shall be circulated indicating in respect of each petition the senator who presents it, the number of signatures, and the subject matter of the petition.

-

Every petition presented shall be deemed to have been received by the Senate unless a motion, moved at the time provided, that a petition be not received, is agreed to.

-

The texts of the petitions received shall be printed in Hansard.

-

A petition shall not be presented after notices of motion have been given, but when the mover of a motion is called or when an order of the day is read for the first time, a petition referring to it may be presented.

-

A senator presenting a petition shall place the senator’s name at the beginning of it, together with a statement of the number of signatures.

-

Petitions may be presented to the Senate only by a senator, and a senator may not present a petition from that senator.

-

A petition not certified under paragraph (1) may be presented in accordance with this standing order with the approval of the President if the President is satisfied that exceptional circumstances warrant its presentation.

Amendment history

Adopted: 19 August 1903 as SOs 71, 72, 84 to 85 and 86 (corresponding to paragraphs (1), (5), (7) and (6) respectively)

Amended:

- [20 November 1974, J.347; re-adopted 18 February 1976, J.24, 8 March 1977, J.5, 22 February 1978, J.21 and 26 November 1980, J.22 (sessional order adopted to change the method by which petitions would be presented in the chamber)]

- [25 November 1982, J.1260; amended 22 February 1985, J.36 (revised sessional order adopted to change the method by which petitions would be presented in the chamber)]

- 6 March 1997, J.1581 (adoption of paragraph (8) to provide that a summary of petitions be circulated at the commencement of each sitting day with a general announcement by the Clerk, and that a petition not in conformity with the order may be presented in accordance with the order only with the approval of the President)

1989 revision: Old SOs 76, 77, 91, 89 and 90 combined into one, restructured into seven paragraphs and renumbered as SO 69; sessional orders incorporated and language simplified

Commentary

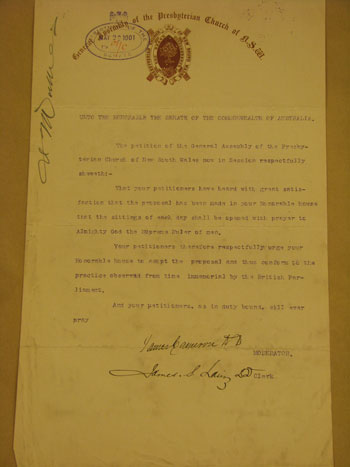

The first petition prestented to the Senate on 21 May 1901 asked the Senate to commence it's proceedings each day with prayers (see SO 50)

On 21 May 1901 the first petition, from the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church of New South Wales, in favour of opening the proceedings of the Senate with daily prayer, was presented to the Senate, following the procedures of the adopted standing orders of South Australian House of Assembly.[1]

The standing orders were adopted on 19 August 1903 in the same form as those contained in the 9 October 1901 draft and were either taken directly from counterparts in the state assemblies (most notably those of Victoria, New South Wales and South Australia) or encoded the practice of the assemblies.[2]

The 1938 MS noted that the standing orders relating to petitions were “so full and detailed that very little remain[ed] to be said”. They were, however, strangely silent on the practicalities of senators presenting petitions to the Senate. Over time, the major impetus for modification to the standing order has been a desire to use the Senate’s time more efficiently. As a matter of practice a senator presenting a petition was restricted to a statement of the parties from whom it came and the number of signatures attached to it, and by reading the prayer of the petition. However, on 30 October 1974, 53 petitions were presented, mostly in reference to the Family Law Bill,[3] the reading of which took 30 minutes.[4] As a result of this, on the same day, notice was given of a motion to refer the process of presenting petitions to the Standing Orders Committee for consideration.

The committee recommended the adoption of a sessional order that would streamline the presentation process. The sessional order codified a ruling by President Givens that a senator could not read a petition in full and that it could only be read by the Clerk after a resolution of the Senate to do so.[5] It allowed for a petition to be presented in one of three ways, after lodgement with the Clerk.[6] First, the senator could choose to personally present his or her petition by stating the subject matter of the petition and the number of signatories to it. Secondly, if the petition had less than 250 words, the senator could ask for the full text of the petition to be read by the Clerk. Otherwise, the Clerk would make an announcement of all other petitions lodged, by stating the subject and number of signatories to the petition.

The process was again streamlined in November 1982[7] by the adoption of sessional orders that allowed only the reading of the subject and number of signatories to the petition by the Clerk, abandoning the former practice of allowing a senator to personally present a petition or to read the full text of the petition. The 1982 sessional orders were amended slightly in 1985 by removing the requirement to announce the identity of petitioners and were subsequently incorporated as paragraphs (2) to (4) in the 1989 revision. Finally, on 6 March 1997, the process was shortened again, by providing for the Clerk to announce that petitions had been lodged in accordance with a list circulated to all senators at the start of the day, in much the same way as documents presented pursuant to statute were announced (see SO 166).[8]

At each step of the process the committee’s main purpose was to consider the more effective use of time available to the Senate. A number of senators opposed the changes, primarily concerned that the process of petitioning the Parliament would be made redundant and that the right of petitioners to have their grievances heard by the Senate would be restricted. However, it was noted that the text of each petition would be publicly available in Hansard. Moreover, the Standing Orders Committee, in 1982, had recommended that the text of all petitions be “referred to the relevant standing committees, so that, should those committees wish to inquire into any particular petitions, they may seek a reference from the Senate to do so”.[9] In practice, this happens rarely. In the mid–1990s the then Environment, Recreation, Communications and the Arts Legislation Committee followed the practice of writing to relevant departments to request responses to issues raised in certain petitions. The committee then reported to the Senate on these responses.[10] The most recent example of committee activity stemming from a petition was in 2006 when, on the motion of Senator Allison (AD, Vic) and other senators, a petition relating to the management and prevention of gynaecological cancers and sexually transmitted infections was referred to the Community Affairs References Committee for response to the Senate. On that occasion, rather than conducting an inquiry the committee held a roundtable discussion on issues involved in the petition. In 1995 the Procedure Committee reported that it did not consider it necessary for the practice of sending petitions to standing committees to be formalised.[11]

The sessional orders relating to the presentation of petitions were ultimately incorporated into the 1989 revision.

Petitions follow a standard format and may contain any number of signatures. Signatories may 'sign up' electronically.

Even though the process of presenting conforming petitions had been streamlined, it was still possible for senators to present non-conforming petitions, by leave, by reading out the full text of the petition and moving that the petition be received. On 27 April 1988, the Deputy Leader of the Opposition in the Senate, Senator Lewis (Lib, Vic) and the Minister for Home Affairs, Senator Ray (ALP, Vic) commented in statements by leave that it appeared that there was an increasing practice of presenting non-conforming petitions on broadcast days.[12] The senators indicated that they would refuse leave on broadcast days to present petitions which were not in conformity with the standing orders.

At various times senators had questioned this process, commenting that allowing non-conforming petitions to be presented in this way afforded them more time and attention than a conforming one.[13] On 5 December 1996 a total of 22 non-conforming petitioning documents were presented, by leave, to the Senate after the Clerk had announced petitions for that day.[14] In each case, the full text of the petition was read out after a request for leave was granted and, after each presentation, a motion was moved that the petition be received. President Reid referred to the Procedure Committee’s Third Report of 1993 which stated:

… documents which do not qualify as petitions should not be presented by leave at the time for petitions except in exceptional circumstances and for compelling reasons, established to the satisfaction of all Senators by the Senator proposing to present the document.[15]

For this reason a reference was made to the Procedure Committee and SO 69(8) was adopted on 6 March 1997 to allow petitions not able to be certified as in conformity (in accordance with SO 69(1)) to be presented only in “exceptional circumstances” in an attempt to curb the practice of senators presenting non-conforming petitions by leave of the Senate. It was hoped that this would both reduce the number of non-conforming petitions being presented and allow for non-conforming petitions to be presented in a way that did not afford them more Senate time than those that conformed with the standing orders. Instead, petitioning documents ought to be tabled, by leave, during a relevant debate, or on the adjournment debate or in discussion of matters of public interest. However, it is still the case that, on occasion, petitioning documents are presented, by leave, at the time for presentation of petitions, potentially giving non-conforming petitions more time and attention from the chamber than conforming ones, subject to the granting of leave.