No. 16 Consideration of legislation (PDF 92KB)

An outline of the process

A significant amount of the Senate's time is spent considering proposed laws (bills). Although any senator may introduce a bill (referred to as a private senator's bill), most bills are introduced by ministers.

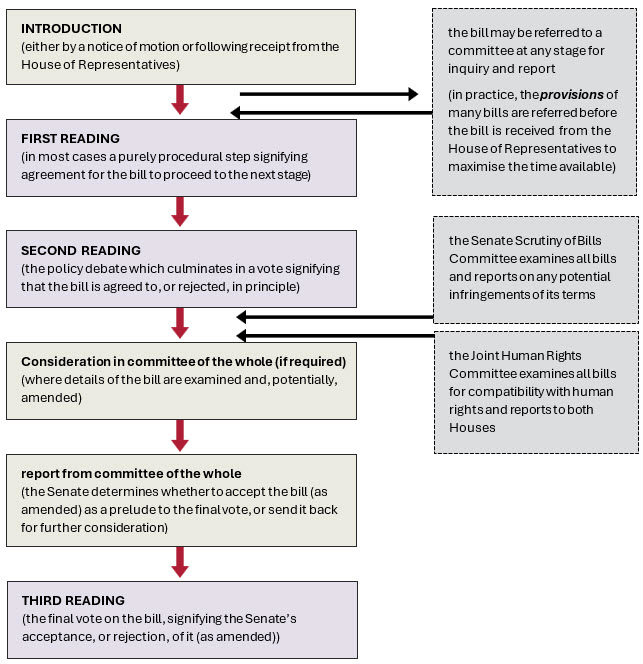

Stages of consideration

Each bill, regardless of its source, is considered in the same way, involving the following steps:

Second reading and committee of the whole debate

A senator may make a second reading speech of up to 15 minutes and a further contribution to any second reading amendment moved after they speak. The second reading debate goes to the principles of a bill. It is opened by a minister who outlines the policies and rationale of the bill and is usually closed by a minister who may respond to issues or concerns raised during the debate.

Debate in committee of the whole is a flexible and interactive process in which the details of the bill are queried and amendments are moved, debated and determined. Although a senator may speak for up to 10 minutes at a time and there is no limit to the number of times a senator can speak, most contributions in committee are short.

What is the "cut-off"?

The cut-off (standing order 111(5)) is a procedure to prevent an end-of sittings rush of legislation. For a bill to be considered by the Senate during a period of sittings (the current period), it must have been introduced in either House in a previous period of sittings. In addition, if it was introduced in the House of Representatives in a previous period of sittings, it must be received by the Senate in the first two-thirds of the current period. A period of sittings is any period during which the Senate is not adjourned for more than 20 days. The final day of the first two-thirds of a sitting period is indicated on the sitting calendar with a scissor icon and any bill received by the Senate after this day will be subject to the cut-off procedure.

The procedure does not apply to private senators' bills.

The Senate may exempt particular bills from the cut-off, allowing them to be considered during the current period. Requests for exemption usually take the form of a notice of motion (see Guide No. 8—Notices of motion) and must be accompanied by an explanation of the need for exemption.

The role of committees

What role do committees play in the consideration of legislation?

When a bill is referred to a committee, the committee usually takes evidence from the minister, officials, interest groups and affected individuals and reports to the Senate. Although the committees may not amend bills, they may recommend amendments for adoption by the Senate.

Referring bills to committees

There are several means of referring bills to committees for inquiry and report. The most commonly used method is via the Selection of Bills Committee. Senators submit proposals to the committee for particular bills to be referred to the relevant Senate standing committee. The committee then makes recommendations to the Senate about bills to be referred, the committees to which they are to be referred, and the reporting dates. Adoption of the report by the Senate has the effect of referring the bills as recommended. The motion for the adoption of the report may be amended to vary the details of the recommendations or to add or delete bills.

Bills may also be referred by way of motion after notice, by an amendment moved to the motion for one of the stages of consideration of a bill (see below), or by a motion moved after the second reading of the bill is agreed to.

The Senate also has a practice of referring 'time critical' bills introduced into the House of Representatives during the budget estimates fortnight to committees before the Senate returns for the June sittings. A committee may decline to examine a time critical bill if, by unanimous decision, it considers that there are no substantive matters requiring consideration (see Guide No. 13—Referring matters to committees).

The Scrutiny of Bills Committee

The Scrutiny of Bills Committee established under standing order 24 examines each bill against a set of scrutiny principles that focus on the effect of proposed legislation on individual rights, liberties and obligations, the rule of law and on parliamentary scrutiny. Where the committee detects a possible infringement, it seeks an explanation from the minister. An outline of the committee's initial concerns and the results of considering the minister's response are presented to the Senate in the Scrutiny Digest. The committee often draws the Senate's attention to problematic provisions in bills and individual senators may move amendments to address the problems.

If the committee has not finally reported on a particular bill because the minister has failed to respond to the committee's concerns on the bill then, immediately before consideration of government business or consideration of the relevant bill, a senator may seek an explanation as to why a response has not been provided.

If the minister provides an explanation, the senator may move without notice that the Senate take note of the explanation. If an explanation is not provided, the senator may move without notice that the Senate take note of the failure to provide an explanation.

The Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights

The Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights was established in 2012 through the enactment of the Human Rights (Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011. The committee examines all bills and legislative instruments for compatibility with international human rights standards.

Amendments and other details

It is important not to confuse two different types of amendments that can be moved during the consideration of legislation:

- amendments to the motions for particular stages of a bill's consideration, which may affect the passage of the bill but not its content; and

- amendments to the text of the bill, which may affect the final content of the law.

Amendments to procedural motions

Amendments may be moved to the procedural motions for particular stages of a bill's consideration. These amendments may add words to, or change words in, the motion to:

- express an opinion about the bill or the government's handling of the related policy issues;

- reverse the effect of the motion so that the bill is defeated at that point;

- refer the bill to a committee; and

- delay further consideration of the bill.

The most common motion amended this way is for the second reading ("That this bill be now read a second time"). Amendments are also sometimes moved to the motion "That the report of the committee be adopted", especially if the committee of the whole stage reveals further action that the Senate may wish to take at the earliest opportunity.

An amendment to the motion for the third reading of a bill which replaces the word "now" with the words "this day six months" has the effect of finally defeating the bill. This amendment is the only one which may be moved to the third reading motion and has its origins in traditional parliamentary practice. It is more common for a Senator wishing to defeat a bill to simply vote against the motion for the second or third reading.

Textual amendments to bills

Hundreds of amendments are moved each year to bills in the Senate. A large number of bills are amended. Non-government senators are assisted by the Clerk Assistant (Procedure) in drafting their amendments while government amendments are usually drafted by the Office of Parliamentary Counsel. Amendments to a bill are distributed in the Chamber, available on the Dynamic Red and from the relevant bill's homepage.

An amendment must be relevant to the subject matter of the bill (see standing order 118). Subject matter is usually assessed by reference to the long title of the bill ("A Bill for an Act to ….") and the explanatory memorandum, although the long title is only an indication of subject matter rather than determinative (see chapter 12 of Odgers' Australian Senate Practice). The relevance rule has always been interpreted liberally.

If senators circulate amendments to a bill, the Table Office will prepare a "running sheet" to help to manage and follow proceedings. A running sheet lists all circulated amendments to a bill in a suggested order. It may also highlight where circulated amendments are identical or may conflict with one another, and if amendments are consequential on others being agreed to.

Proceedings in committee of the whole

It is practice for bills to be "taken as a whole", meaning that the entire bill is before the committee and available for amendment, not necessarily in a sequential manner as outlined in standing order 117 .

When a bill is taken as a whole, the chair puts the question on each amendment, or group of amendments, or on each amendment to an amendment. When all amendments have been dealt with, the final question is "That the bill, as amended, be agreed to" or, if no amendments have been agreed to, "That the bill stand as printed". Only one amendment may be before the chair at a time, but, in practice, amendments are frequently moved together in groups by leave (unanimous consent of senators present).

The question on an amendment to delete a clause, item or proposed new section (or a larger unit such as a Subdivision, Division, Part or Schedule) is put in the form "That the [unit] stand as printed". This is designed to test whether the unit has majority support. An equally divided vote on that question results in it being decided in the negative and the unit being removed from the bill. If, on the other hand, the question took the form of "That the amendment [to omit the unit] be agreed to", an equally divided vote would result in that question being lost and a unit which did not have majority support remaining in the bill. Amendments of this type are usually drafted in the form, "[unit], to be opposed" and are always put by the chair separately from other amendments (see below and Guide No.3—Voting in the Senate).

Requests

The Senate sometimes requests the House of Representatives to make amendments that the Senate is prevented by the Constitution from making itself. Under section 53 of the Constitution, the Senate may not amend:

- a bill imposing taxation; or

- a bill appropriating money for the ordinary annual services of government.

Any amendments proposed by the Senate to such bills must take the form of requests.

In addition, the Senate may not amend a bill "so as to increase any proposed charge or burden on the people". Such amendments must also take the form of requests.

The interpretation of this provision is not entirely settled. As it refers to "proposed laws" it cannot be interpreted by the High Court.

When drafting amendments for non-government senators, the Clerk Assistant (Procedure) provides advice to senators on whether an amendment may need to take the form of a request for an amendment.

Any circulated requests must be accompanied by a statement explaining why the amendments had been framed as requests and a statement by the Clerk of the Senate on whether the amendments would be regarded as requests under the precedents of the Senate. The former statement is prepared by the Office of Parliamentary Counsel for government ministers' requests and by the Clerk Assistant (Procedure) for non-government senators' requests.

The third reading of bills to which requests have been made is deferred until the House of Representatives responds and the Senate accepts the House's response.

What happens when the Senate amends a bill?

When the Senate amends a bill introduced in the House of Representatives, the Senate returns the bill to the House with a list (or schedule) of the amendments it has made and asks the House to agree to them. The House may accept or reject the amendments, amend them or agree to substitute amendments. Unless the House accepts the amendments, the bill is returned to the Senate for further action. The Senate may insist on its original amendments, make substitute amendments or may decide not to insist on its amendments. Areas of the bill that have been agreed to by both Houses may not be revisited except to make amendments that are consequential on the House's rejection of the Senate's amendments. These negotiations between the Houses (in the form of messages—see Guide No. 18—Communications between the Houses—Dealing with messages) are dealt with in committee of the whole to provide maximum procedural flexibility.

A similar process is followed if the Senate has agreed to a bill subject to with requests. The House of Representatives may make the amendments requested by the Senate or decide not to. On its return to the Senate, the Senate may press its requests for the House to make the amendments or decide not to. After the issue is resolved, the Senate votes on the third reading of the bill.

When the Senate amends a bill introduced first in the Senate, the amendments are incorporated into the bill which is reprinted before being sent to the House for agreement. This is known as a third reading print and the cover of the bill indicates that it is "as read a third time". Any disagreements about amendments then made by the House are handled in the manner described above.

When both Houses have agreed to a bill in identical terms, perhaps after several rounds of negotiations, the bill is assented to by the Governor-General. If agreement cannot be reached, the bill may be laid aside. For possible consequences of failure to agree, see section 57 of the Constitution which provides for the dissolution of both Houses and the convening of a joint sitting under certain circumstances.

Need assistance?

For information about the progress of bills, see the Senate daily and weekly summaries, and the Senate Bills List.

Government senators and their staff should contact the Clerk Assistant (Table) on extension 3020 or ca.table.sen@aph.gov.au. Non-government senators and their staff should contact the Clerk Assistant (Procedure) on extension 3380 or ca.procedure.sen@aph.gov.au.

For general advice and documents contact the Senate Table Office on extension 3010.

Last reviewed: June 2025