23

October 2020

PDF version [480KB]

Geoff

Gilfillan

Statistics and Mapping Section

Introduction

The restrictions imposed by Federal, State

and Territory Governments to limit the spread of COVID-19 have had different

labour market impacts across demographic groups, industries and regions.

This paper draws on the results of two Australian Bureau of

Statistics (ABS) data series that shed light on the extent of the impact of

COVID-19 on the Australian labour market. The two data series are the Weekly

Payroll Jobs and Wages in Australia series (which had its first release on

4 April 2020) and the long established Labour

Force survey. The Weekly Payroll Jobs and Wages series shows percentage

changes in jobs and wages for employees whereas the Labour Force series

captures change in the number of people that are employed, unemployed or

not in the labour force.

Contents

Introduction

Executive Summary

Impact on jobs and wages

Change in jobs and wages by age

Table 1: percentage change in jobs and

wages by age, 14 March to 3 October 2020

Change in jobs and wages by gender

Table 2: percentage change in jobs and

wages by gender, 14 March to 3 October 2020

Change in jobs by firm size

Table 3: percentage change in jobs and

wages by firm size, 14 March to 3 October 2020

Change in jobs and wages by industry

Table 4: percentage change in jobs and

wages by industry, 14 March to 3 October 2020

Change in jobs and wages by

state/territory

Table 5: percentage change in jobs and

wages by state/territory, 14 March to 3 October 2020

Change in jobs by region

Table 6: percentage change in payroll

jobs, 14 March to 3 October 2020

Impact on employment, unemployment,

participation and hours worked

Employment by age

Chart 1: change in employment by age,

March to September 2020

Unemployment by age

Chart 2: change in unemployment by

age, March to September 2020

Chart 3: change in unemployment rates

by age, March to September 2020

Labour market impacts by gender

Chart 4: change in key labour market

indicators by gender, March to September 2020

Table 7: change in full-time and

part-time employment by gender, March to September 2020

Hours worked by gender

Chart 5: hours worked by gender, March

to September 2020

Chart 6: percentage change in monthly

hours worked by gender, March to September 2020

Change in employment by state and

territory

Chart 7: change in employment by

state/territory, March to September 2020

Change in unemployment rates by state

and territory

Chart 8: unemployment rate by

state/territory, March to September 2020

Change in labour force participation

by state and territory

Chart 9: change in participation rates

for states and territories, May to September 2020

Impact on industries

Table 8: change in employment by

industry, February to August 2020

Impact on casual and permanent

employees and owner managers

Table 9: change in permanent and

casual employees, February to August 2020

Chart 10: change in employees and

owner managers, March to August 2020

Impact on numbers of people receiving

unemployment benefits

Table 10: JobSeeker Payment and Youth

Allowance (Other) recipients, March and August 2020

Executive

Summary

The various data sources available show since restrictions

were put in place to limit the spread of COVID-19 in March 2020:

- Job loss has been greatest in percentage terms in Accommodation

and food services and Arts and recreation services.

- People aged 20 to 29 years and those aged 60 years or more have

been impacted the most in terms of job loss.

- Workers aged 40 years and over have experienced greater loss of

wages.

- Employment loss and increases in unemployment has been greatest

for those aged 20 to 34 years.

- The outcomes are less clear for people aged under 20 years with

one data source showing growth in jobs and another source showing a decline in

employment.

- Men have been affected slightly more than women in terms of rate

of job loss and decline in numbers of employed, but much more affected in terms

of rate of wages loss and change in numbers of underemployed.

- Casual workers accounted for a significant share of the decline

in employees.

- Full-time workers have been affected far more in terms of

employment loss than part-time workers.

-

There has been little change in the number of business operators

but a substantial decrease in employees of private and public enterprises.

- Men and younger people experienced larger increases in unemployment

beneficiaries.

Impact on

jobs and wages

The ABS Weekly

Payroll Jobs and Wages in Australia series shows the change in the number

of paid payroll jobs in the economy as well as the change in total wages paid

by employing enterprises. The series picks up changes in the labour market

since 14 March 2020 when Australia recorded its 100th confirmed case of

COVID-19.

The data series draws on Single Touch Payroll (STP) data

provided to the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) by businesses that have

STP-enabled payroll or accounting software and is collected fortnightly when

businesses run their payroll. The data enables identification of age, sex,

industry and region of employees engaged in paid jobs. Employees can hold

multiple jobs but each job is counted separately. Data is not available on

whether employees work full-time or part-time or whether they are employed on a

casual or permanent basis.

The STP data captures the activities of 99 per cent of

medium and larger enterprises (those employing 20 people or above) and around

71 per cent of small businesses (employing less than 20 people) who were reporting

through the STP system. Some small businesses have been granted concessions to

enable a longer transition period to mandatory STP reporting. Given the series

is not capturing all jobs in the Australian labour market, an index is used by

the ABS to enable measurement of percentage changes over time rather than

providing estimates of change in the number of jobs or value of wages.[1]

The advantage of the STP series is the data is available

fortnightly rather than monthly as is the case for the ABS Labour Force survey.

This has enabled more timely releases of information which can highlight

recovery, deterioration or stability in the labour market. It should be

emphasised that the STP data refers to change in jobs and wages whereas

the Labour Force survey data refers to the number of people that are

employed, unemployed or not in the labour force.

Change in

jobs and wages by age

People aged 20 to 29 years and 60 years and over have been

more heavily impacted by COVID-19 compared with other age groups in terms of

job loss (see table 1). People aged 70 years or more experienced the largest

reduction in payroll jobs (down 12.1%) between 14 March 2020 and 3 October 2020,

followed by those aged 60 to 69 years (down 6.4%) and people aged 20 to 29

years (down 6.1%). In contrast, younger people aged under 20 years experienced

jobs growth of 6.1%—possibly due to the attraction of lower costs of

hiring younger workers. People aged 20 to 29 years accounted for 20.8 per cent

of all employed people in September 2020, those aged 60 years and over

accounted for 10.9% and those aged 15 to 19 years accounted for 4.8%.[2]

Wages fell more substantially for people aged 40 years and

over in the six and a half months to early October. Wages for people aged 40 to

49 years were 4.5% lower. And wages for those aged 50 to 59 years and 60 to 69

years fell by 4.9% and 7.2% respectively. The wage and job loss outcome for

older people is likely to be particularly concerning for those trying to build

up their savings as they near retirement.

Table 1: percentage change in jobs and

wages by age, 14 March to 3 October 2020

| Age |

Payroll jobs |

Total wages |

19 September

to 3

October |

14 March to 3

October |

19 September

to 3

October |

14 March to 3

October |

| Under 20 |

2.8% |

6.1% |

1.1% |

29.6% |

| 20 to 29 years |

-0.8% |

-6.1% |

-1.2% |

0.7% |

| 30 to 39 years |

-1.1% |

-3.6% |

-2.3% |

-2.6% |

| 40 to 49 years |

-1.0% |

-2.7% |

-3.2% |

-4.5% |

| 50 to 59 years |

-0.7% |

-2.8% |

-2.3% |

-4.9% |

| 60 to 69 years |

-0.9% |

-6.4% |

-1.4% |

-7.2% |

| 70 years plus |

-1.9% |

-12.1% |

-2.5% |

-8.3% |

| All persons |

-0.9% |

-4.1% |

-2.2% |

-3.3% |

Source: ABS, Weekly Payroll Jobs and Wages in Australia, cat. no. 6160.0.55.001

Wages increased significantly for workers aged under 20

years in the six months to early October (up 29.6%). This wage outcome could be

partly due to access to a flat fortnightly rate of $1,500 for the JobKeeper

Payment for all employees stood down, regardless of age and previous hours of

work. Employees also needed to have been with their employer for 12 months or

more.[3]

The JobKeeper payment was made available to businesses and organisations experiencing

a substantial decline in revenue due to COVID-19 restrictions. Many workers

aged 20 years and under would have been earning less than the JobKeeper Payment

rate (in lower paid part-time casual jobs) prior to being stood down.[4]

Change in

jobs and wages by gender

Job loss for males was slightly higher than jobs loss for

females between 14 March and 3 October—at 5.0% compared with 4.2%. But

wage loss for men was far greater—down 5.6% compared with a loss of 0.4%

for women (see table 2). The gender difference in wage outcomes is partly due

to men having a much greater likelihood of working full-time hours than women

in the pre-COVID-19 environment. Full-time workers stood down would experience

a much bigger reduction in hours worked than part-time workers. A contributing

factor to the lower rate of wage loss for women is women were more likely to

have lost jobs that were part-time and lower paid compared with the loss of

full-time jobs for men[5]

Table 2: percentage change in jobs

and wages by gender, 14 March to 3 October 2020

| Gender |

Payroll jobs |

Total wages |

19 September

to 3

October |

14 March to 3

October |

19 September

to 3

October |

14 March to 3

October |

| Males |

-1.1% |

-5.0% |

-2.3% |

-5.6% |

| Females |

-0.9% |

-4.2% |

-2.3% |

-0.4% |

| All persons |

-0.9% |

-4.1% |

-2.2% |

-3.3% |

Source: ABS, Weekly Payroll Jobs and Wages in Australia, cat. no. 6160.0.55.001

Change in

jobs by firm size

On average, across industry sectors, employees of small and

medium sized firms have borne the brunt of job loss in the six and a half months

to early October (down 6.3% and 6.9% respectively). In comparison jobs fell by only

1.6% for large businesses (see table 3). Part of the explanation for the

difference in rates of job loss is small and medium businesses are more likely

to employ casual workers.[6]

Casual employees accounted for three quarters of the fall in employees between

February and August 2020.[7]

Table 3: percentage change in jobs

and wages by firm size, 14 March to 3 October 2020

| Firm size |

Payroll jobs |

| 19 September to 3

October |

14 March to 3

October |

| Small (under 20 employees) |

-2.6% |

-6.3% |

| Medium (20 to 199 employees) |

-1.2% |

-6.9% |

| Large (200 employees plus) |

0.1% |

-1.6% |

| All firms |

-0.9% |

-4.1% |

Source: ABS, Weekly Payroll Jobs and Wages in Australia, cat. no. 6160.0.55.001

The largest job loss in small businesses over the six and a

half months to early October was recorded in Victoria (down 11.0%), New South

Wales (down 6.6%), and Tasmania (down 5.6%).

Change in

jobs and wages by industry

Industries most heavily affected by trading restrictions to

combat the spread of COVID-19 such as Accommodation and food services and Arts

and recreation services were also the most affected by job loss between 14 March

and 3 October (down 17.4% and 12.9% respectively) (see table 4).

Table 4: percentage

change in jobs and wages by industry, 14 March to 3 October 2020

| Industry |

Payroll jobs |

Total wages |

19

September

to 3

October |

14 March

to 3

October |

19

September to 3

October |

14 March

to 3

October |

| Agriculture, forestry & fishing |

-2.3% |

-8.1% |

-2.0% |

-3.5% |

| Mining |

-0.4% |

-2.1% |

8.3% |

-6.4% |

| Manufacturing |

-0.2% |

-3.6% |

0.6% |

-6.2% |

| Electricity, gas, water & waste services |

-3.7% |

-2.1% |

-6.8% |

2.4% |

| Construction |

-1.7% |

-5.4% |

-1.2% |

-7.0% |

| Wholesale trade |

-0.8% |

-4.5% |

-0.1% |

-9.6% |

| Retail trade |

-0.8% |

-4.1% |

0.0% |

-2.3% |

| Accommodation & food services |

0.4% |

-17.4% |

-2.5% |

-13.0% |

| Transport, postal & warehousing |

-1.0% |

-6.1% |

1.3% |

-4.6% |

| Information media & telecommunications |

-1.7% |

-9.5% |

-16.5% |

-5.6% |

| Financial & insurance services |

0.0% |

2.2% |

-22.8% |

-3.9% |

| Rental, hiring & real estate services |

-1.0% |

-6.3% |

-0.2% |

-0.3% |

| Professional, scientific & technical services |

-2.3% |

-4.7% |

-1.0% |

-5.1% |

| Administrative & support services |

-1.1% |

-5.1% |

-1.2% |

-2.7% |

| Public administration & safety |

-1.3% |

2.4% |

0.7% |

0.3% |

| Education & training |

0.8% |

-2.4% |

0.1% |

0.2% |

| Health care & social assistance |

-1.0% |

0.8% |

-0.4% |

3.1% |

| Arts & recreation services |

-1.2% |

-12.9% |

-0.9% |

-7.9% |

| Other services |

-1.9% |

-5.6% |

-1.9% |

1.6% |

| All industries |

-0.9% |

-4.1% |

-2.2% |

-3.3% |

Source: ABS, Weekly Payroll Jobs and Wages in Australia, cat. no. 6160.0.55.001

In contrast, some industries were able to expand slightly in

terms of job growth despite the restrictions including Public administration

and safety (up 2.4%), Financial and insurance services (up 2.2%) and Health

care and social assistance (up 0.8%). The rate of job loss in Accommodation and

food services was similar for females and males (down 19.1% and 19.0%

respectively). In Arts and recreation services job loss was slightly higher for

females (down 13.5%) compared with males (down 12.1%). Job loss in both

industries was highest for those aged 20 to 29 years (down 24.4% and 15.9%

respectively).[8]

In the fortnight to 3 October jobs growth was only experienced in two

industries—Education and training and Accommodation and food services (up

0.8% and 0.4% respectively).

Wage falls in the six and a half months to early October was

most significant in Accommodation and food services (down 13.0%), followed by

Wholesale trade (down 9.6%) and Arts and recreation (down 7.9%). Moderate growth

in wages was recorded in Health care and social assistance (up 3.1%) and Electricity,

gas and water (up 2.4%). In the fortnight to 3 October 2020 very large falls in

wages were recorded in Financial and insurance services (down 22.8%) and

Information, media and telecommunications (down 16.5%). The 8.3% increase in

wages in the mining industry could be influenced by seasonal bonuses.[9]

Change in

jobs and wages by state/territory

Job loss has been more pronounced in the state of Victoria

in the six and a half months to early October (down 7.7%) (see table 5). Tasmania

and New South Wales recorded the biggest falls in wages (down 4.9% and 4.8%

respectively). Western Australia experienced the smallest rate of job loss (at

1.0%)—possibly due the continued strength of the mining industry, less

dependence on service industries and easing of restrictions on service

industries earlier than some other jurisdictions. South Australia recorded no

change in total wages despite a 2.5% fall in payroll jobs. All jurisdictions

recorded a fall in jobs in the fortnight to 3 October.

Table 5: percentage change in jobs and

wages by state/territory, 14 March to 3 October 2020

| State/territory |

Payroll jobs |

Total wages |

19 September

to 3

October |

14 March to 3

October |

19 September

to 3

October |

14 March to 3

October |

| New South Wales |

-0.8% |

-3.6% |

-4.5% |

-4.8% |

| Victoria |

-0.9% |

-7.7% |

-1.4% |

-4.2% |

| Queensland |

-1.0% |

-2.5% |

-1.4% |

-0.9% |

| South Australia |

-0.7% |

-2.5% |

-1.1% |

0.0% |

| Western Australia |

-1.0% |

-1.0% |

0.4% |

-2.1% |

| Tasmania |

-1.0% |

-4.5% |

-2.3% |

-4.9% |

| Northern Territory |

-1.2% |

-2.1% |

-0.9% |

-1.4% |

| Australian Capital Territory |

-0.9% |

-4.3% |

-1.4% |

-2.5% |

| Australia |

-0.9% |

-4.1% |

-2.2% |

-3.3% |

Source: ABS, Weekly Payroll Jobs and Wages in Australia, cat. no. 6160.0.55.001

Change in

jobs by region

Table 6 shows where the ten largest and smallest decreases

in jobs have occurred in regions of Australia between 14 March and 3 October

(at the Statistical Area 4 (SA4) level).

Table 6: percentage change in payroll jobs, 14 March

to 3 October 2020

| Regions (SA4s) |

Payroll jobs |

| 14 March to 3

October |

| Largest decreases |

|

| Melbourne – Inner |

-10.1% |

| Melbourne – North West |

-8.5% |

| Melbourne — South East |

-8.3% |

| Melbourne – Inner South |

-8.2% |

| Mornington Peninsula (Vic) |

-8.1% |

| Latrobe – Gippsland (Vic) |

-7.9% |

| Melbourne - West |

-7.8% |

| Melbourne — Inner East |

-7.6% |

| Sydney – City and Inner South |

-7.6% |

| North West Victoria |

-7.3% |

| Smallest decreases |

|

| Perth – South West |

-1.5% |

| Bunbury (WA) |

-1.6% |

| Illawarra (NSW) |

-1.9% |

| Newcastle and Lake Macquarie (NSW) |

-2.0% |

| Mandurah (WA) |

-2.0% |

| Perth – North East |

-2.1% |

| Perth – North West |

-2.1% |

| Central Queensland |

-2.2% |

| Perth – South East) |

-2.2% |

| Hunter Valley exc Newcastle (NSW) |

-2.3% |

| All regions |

-4.1% |

Source: ABS, Weekly Payroll Jobs and Wages in Australia, cat. no. 6160.0.55.001

Regions within metropolitan Melbourne and regional Victoria

account for a substantial proportion of the regions experiencing the largest

loss of jobs between mid-March and early October 2020. Parts of metropolitan

Perth and regions within non-metropolitan WA and NSW account for the majority

of SA4s experiencing the smallest falls in jobs.

Impact on

employment, unemployment, participation and hours worked

ABS Labour

Force survey data shows people in younger age groups have been the most

affected by restrictions imposed to combat the spread of COVID-19, with larger

decreases in employment and larger increases in unemployment than people in

other age groups.

Employment

by age

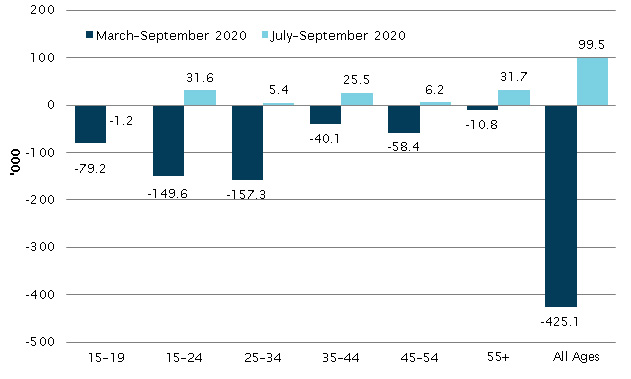

Employment for people aged 25 to 34 years fell by 157,300

(or 5.1%) while employment for people aged 15 to 24 years fell by 149,600 (or

7.7%). There have been signs of a modest recovery in employment for those aged

15 to 24 years more recently with an increase of 31,600 in the two months to

September 2020. But there have been less signs of an improvement in employment

outcomes for people aged 25 to 34 years (up 5,400) (see chart 1).

In contrast to the STP data that showed a 6.1% increase in

jobs for those aged under 20 years in the six and a half months to early

October, ABS Labour Force survey data shows employment for those aged 15 to 19

years fell by 79,200 (or 11.5%) between March and September.

It is not immediately clear as to why these estimates are

moving in different directions but it has been established that young people

are more likely to be multiple job holders[10]

which may be influencing the growth in jobs shown in the STP estimates.

Chart 1: change in employment by age,

March to September 2020

Source: ABS, Labour Force,

cat. no. 6202.0, Table 22, seasonally adjusted

Unemployment

by age

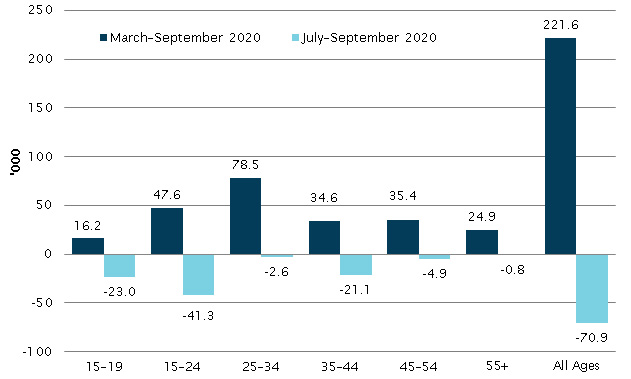

People aged 25 to 34 years recorded the biggest increase in

unemployment between March and September 2020 (up 78,500 or 50.9%) with only a

very small decline (of 2,600) in the most recent two months (see chart 2).

Young people aged 15 to 24 years experienced the next

biggest increase in unemployment (up 47,600 or 18.7%) in the six months to

September 2020 but recorded a substantial fall in unemployment in the past two

months (down 41,300 or 12.0%).

Total unemployment in Australia reached just over 1 million for

the first time in July 2020, but has since fallen to 937,400 in September.[11]

Total unemployment is up by 221,600 (or 31.0%) since March.

Chart 2: change

in unemployment by age, March to September 2020

Source: ABS, Labour Force,

cat. no. 6202.0, Table 22, seasonally adjusted

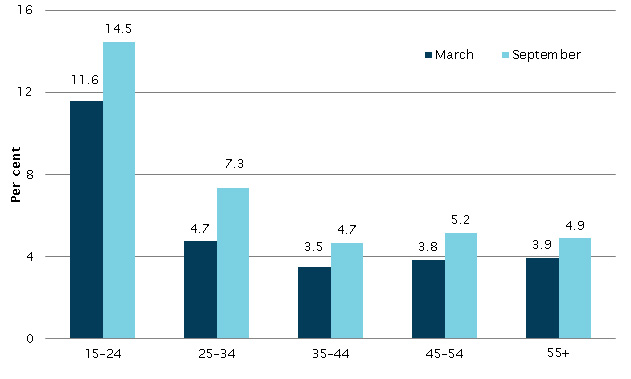

In the period between March and September 2020 people aged

15 to 24 years experienced the largest increase in their unemployment rate (up

2.9 percentage points to 14.5%) followed by those aged 25 to 34 years (up 2.6

percentage points to 7.3%) (see chart 3).

Chart 3: change

in unemployment rates by age, March to September 2020

Source: ABS, Labour Force,

cat. no. 6202.0, Table 22, seasonally adjusted

Labour market impacts by gender

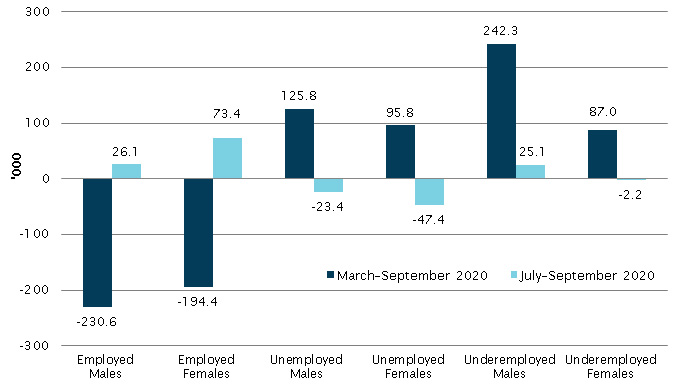

Chart 4 shows men recorded a larger fall in employment than

women in the six months to September 2020, a larger increase in the number of

unemployed and a much bigger increase in underemployment.[12]

In the two months to September, women experienced a larger rebound in

employment than men, a larger fall in unemployment than men, and a small

contraction in underemployment compared with an increase for men.

Chart 4: change in key labour

market indicators by gender, March to September 2020

Source: ABS, Labour Force,

cat. no. 6202.0, Table 22, seasonally adjusted

Employment for men fell by 230,600 (or 3.4%) between March

and September 2020 while employment for women fell by 194,400 (or 3.2%).

Unemployment for men increased by 125,800 (or 32.8%) which compares with a

95,800 increase for women (or 28.8%). Men recorded a much bigger increase in

underemployment—up 242,300 (or 46.7%)—compared with an increase of

87,000 (or 12.6%) for women.

A larger drop in full-time employment compared with

part-time employment was recorded nationally between March and September 2020

(down 331,100 (or 3.7%) and 93,900 (or 2.3%) respectively). Total employment

across the economy fell by 425,100 or 3.3%. [13]Men

and women were affected differently with men experiencing a slightly larger percentage

fall in full-time employment (a fall of 4.0% compared with a fall of 3.4%) than

women and women recording a larger fall in part-time employment than men (a

fall of 2.9% compared with a fall of 0.9%) (see table 7).

Table 7: change in full-time and

part-time employment by gender, March to September 2020

| |

Full-time |

Part-time |

Total |

| Males |

|

|

|

| March 2020 (‘000) |

5 531.7 |

1 315.8 |

6 847.5 |

| September 2020 (‘000) |

5 312.6 |

1 304.3 |

6 616.8 |

| Change – March to September 2020 |

|

|

|

| ‘000 |

-219.1 |

-11.5 |

-230.6 |

| % |

-4.0 |

-0.9 |

-3.4 |

| Females |

|

|

|

| March 2020 (‘000) |

3 339.7 |

2 809.8 |

6 149.5 |

| September 2020 (‘000) |

3 227.7 |

2 727.4 |

5 955.1 |

| Change – March to September 2020 |

|

|

|

| ‘000 |

-112.0 |

-82.4 |

-194.4 |

| % |

-3.4 |

-2.9 |

-3.2 |

| Total |

|

|

|

| March 2020 (‘000) |

8 871.4 |

4 125.6 |

12 997.0 |

| September 2020 (‘000) |

8 540.3 |

4 031.7 |

12 571.9 |

| Change – March to September 2020 |

|

|

|

| ‘000 |

-331.1 |

-93.9 |

-425.1 |

| % |

-3.7 |

-2.3 |

-3.3 |

Source: ABS, Labour Force,

cat no 62020, Table 1.

Hours worked

by gender

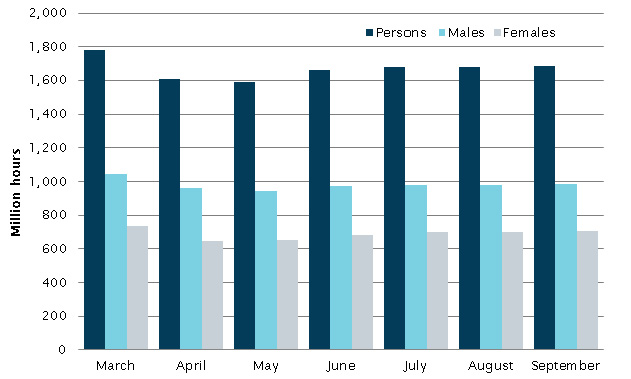

Chart 5 plots the number of hours worked by males and

females from March to September 2020 including the big drop hours in worked in

April, a smaller fall in May and a slow recovery since.

Chart 5: hours worked by gender, March

to September 2020

Source: ABS, Labour Force,

cat. no. 6202.0, Table 22, seasonally adjusted

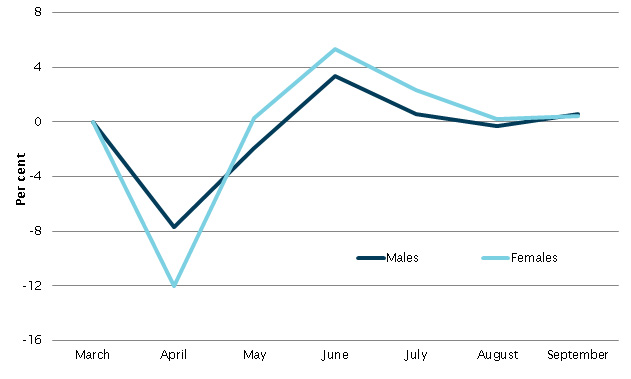

Chart 6 shows women experienced a more substantial fall in

April 2020 (down 12.0% for women and 7.7% for men) but have experienced a

slightly higher monthly percentage increase in hours worked than men in all

months since apart from September 2020.

Chart 6: percentage change in

monthly hours worked by gender, March to September 2020

Source: ABS, Labour Force,

cat. no. 6202.0, Table 22, seasonally adjusted

Average weekly hours worked by men has fallen from 38.0

hours in March 2020 to 37.1 hours in September (a fall of 2.4%) while average

weekly hours worked by women has fallen from 30.0 hours per week to 29.6 hours

(a fall of 1.2%).[14]

There were 903,500 people who worked fewer than their usual

hours for economic reasons [15]in

September 2020, which compares with 1,781,500 in April—a fall of 878,000

or almost one half.[16]

There have been substantial monthly swings in the numbers of

people working zero hours in the six months to September 2020—increasing

by 690,400 in April following the imposition of trading restrictions in March

(to 766,900). This was followed by a fall in the number of people working zero

hours of just under 400,000 in May as some people who were stood down returned

to work. The number of people working zero hours was last recorded at 198,700

in September which compares with 76,500 in March before the restrictions were

introduced.[17]

Since July, in all states and territories except Victoria,

the number of people working zero hours for economic reasons has remained

relatively steady or decreased slightly. In Victoria, the number of people

working zero hours for economic reasons almost doubled between July and August.

Victoria accounted for almost 60% of people working zero hours for economic

reasons in September 2020.[18]

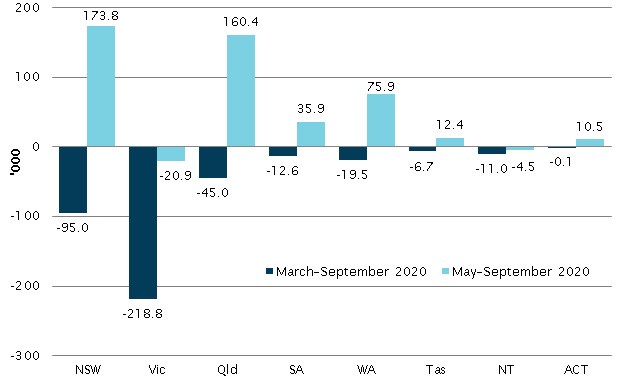

Change in

employment by state and territory

Victoria has been by far the hardest hit jurisdiction in

terms of loss of employment (at 218,800) between March and September 2020,

followed by New South Wales (down 95,000).

Chart 7: change

in employment by state/territory, March to September 2020

Source: ABS, Labour Force,

cat. no. 6202.0, Table 22, seasonally adjusted for the states and original data

for the two territories

National employment fell to just over 12.1 million in May

2020. Since May there has been a strong recovery in employment in New South

Wales (up 173,800), Queensland (up 160,400) and Western Australia (up 75,900).

In contrast employment fell in Victoria (down 20,900) and the Northern

Territory (down 4,500). The decline in employment in Victoria is directly

related to strict lockdown procedures enforced to counter a second wave of

COVID-19 infections. The falling employment outcome for the Northern Territory

is likely to be related to a decline in domestic and international tourism

activity as well as a combination of other factors. International visitor

numbers were down 21% in the Northern Territory in 2019-20 compared with the

previous financial year.[19]

Domestic visitors to the Northern Territory were down 18% in 2019-20 compared

with the previous financial year and domestic tourist spending was down 26%.[20]

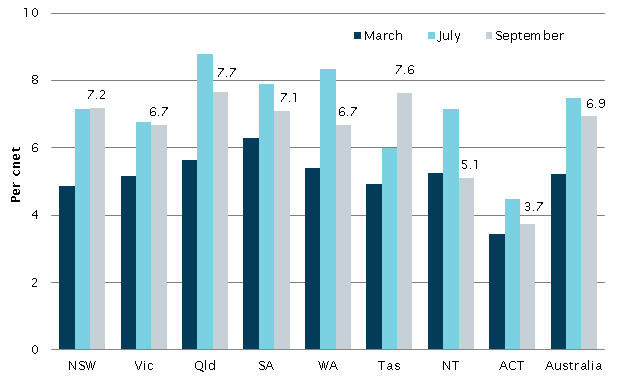

Change in

unemployment rates by state and territory

Chart 8 shows the unemployment rate for each state and

territory for March, July and September 2020. Between July and September the

unemployment rate in New South Wales and Victoria has remained relatively

stable. In the same time period the unemployment rate fell substantially in

Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia, the Northern Territory and the

ACT, but increased in Tasmania. Movements in the unemployment rate for the

territories and smaller states (such as Tasmania) are much more volatile from

month to month compared with larger jurisdictions. However, it is notable that

the participation rate in Tasmania has been rising steadily between May and

September (up from 57.4% to 61.1%) which has contributed to a higher

unemployment rate in the state as entrants into the labour market have found it

harder to find work in the current economic environment.

Chart 8: unemployment rate by

state/territory, March to September 2020

Source: ABS, Labour Force,

cat. no. 6202.0, Table 22, seasonally adjusted for the states and original data

for the two territories

Change in

labour force participation by state and territory

Labour force participation is another indicator that can

shed light on the health of the economy. An increasing participation rate is a

sign of confidence within job seekers that they can enter the labour market and

find work. The labour force participation rate in Australia fell to 62.7% in

May 2020 which compares with 65.9% in March. Since May the labour force participation

rate has increased nationally to 64.8% in September.

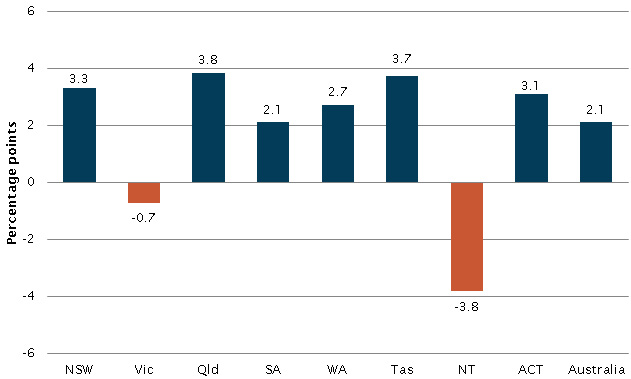

Chart 9 shows the extent of changes in labour force

participation rates in the state and territories since May. All states and

territories apart from Victoria and the Northern Territory have been

characterised by increasing participation rates.

Chart 9: change in participation

rates for states and territories, May to September 2020

Source: ABS, Labour Force,

cat. no. 6202.0, Table 22, seasonally adjusted for the states and original data

for the two territories

Impact on

industries

Table 8 shows the impacts of restrictions imposed to limit

the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic on employment by industry in Australia.

Note that the data available has a starting month of February—prior to

restrictions being imposed—and the latest data available is for August

2020.

The industries most affected by employment loss were

Accommodation and food services (down 18.2%), Arts and recreation services

(down 17.9%), Other services (down 11.3%), Administrative and support services

(down 11.1%) and Information, media and telecommunications and Transport,

postal and warehousing (both down 8.2%).

In contrast, some industries are faring much better and are

even expanding. For example, employment in Electricity, gas, water and waste

services increased by 15,100 (or 11.1%) between February and August, while

employment increased in Agriculture, forestry and fishing by 22,400 (or

6.6%)—driven in part by improvement in climatic conditions.

Other industries experiencing employment growth included Wholesale

trade (up 4.2%), Public administration and safety (up 3.9%), Financial and

insurance services (up 1.6%), Education and training (up 1.3%) and Mining and Rental,

hiring and real estate services (both up 0.7%).

Table 8: change in employment by

industry, February to August 2020

| Industry |

February

2020 |

August 2020 |

Change —

February to

August 2020 |

| ‘000 |

‘000 |

‘000 |

% |

| Agriculture, forestry & fishing |

337.5 |

359.9 |

22.4 |

6.6 |

| Mining |

238.9 |

240.5 |

1.6 |

0.7 |

| Manufacturing |

909.6 |

843.9 |

-65.7 |

-7.2 |

| Electricity, gas, water & waste services |

136.2 |

151.3 |

15.1 |

11.1 |

| Construction |

1 182.4 |

1 152.4 |

-30.0 |

-2.5 |

| Wholesale trade |

386.0 |

402.1 |

16.1 |

4.2 |

| Retail trade |

1 261.1 |

1 196.7 |

-64.4 |

-5.1 |

| Accommodation & food services |

929.8 |

760.7 |

-169.1 |

-18.2 |

| Transport, postal & warehousing |

667.1 |

612.5 |

-54.6 |

-8.2 |

| Information media & telecommunications |

211.7 |

194.2 |

-17.4 |

-8.2 |

| Financial & insurance services |

474.8 |

482.4 |

7.6 |

1.6 |

| Rental, hiring & real estate services |

213.9 |

215.4 |

1.5 |

0.7 |

| Professional, scientific & technical services |

1 172.7 |

1 118.5 |

-54.2 |

-4.6 |

| Administrative & support services |

450.2 |

400.2 |

-50.0 |

-11.1 |

| Public administration & safety |

829.6 |

862.0 |

32.3 |

3.9 |

| Education & training |

1 097.6 |

1 111.7 |

14.1 |

1.3 |

| Health care & social assistance |

1 800.1 |

1 772.4 |

-27.7 |

-1.5 |

| Arts & recreation services |

251.9 |

206.7 |

-45.2 |

-17.9 |

| Other services |

493.2 |

437.6 |

-55.6 |

-11.3 |

| All industries |

13 044.3 |

12 521.1 |

-523.2 |

-4.0 |

Source: ABS, Labour

Force, cat. no. 6291.0.55.003, Table 04 (original data)

Employment loss for women working in Accommodation and food

services was slightly higher than employment loss for men. Employment in the

sector for women fell by 94,400 (or 18.4%) between February and August 2020

which compares with loss of employment of 74,700 (or 18.0%) for men.

For men employment loss was highest in Accommodation and

food services, followed by Transport, postal and warehousing (down 70,400 or

13.2%), Construction (down 50,600 or 4.9%), and Manufacturing (down 48,400 or

7.5%). For women employment loss was greatest in Accommodation and food

services, followed by Retail trade (down 56,900 or 8.0%); Professional,

scientific and technical services (down 53,600 or 10.3%); and Administrative

and support services (down 36,500 or 16.0%). Men recorded much smaller falls in

employment than women in Retail trade (down 7,500 or 1.4%) and Professional,

scientific and technical services (down 500 or 0.1%)[21]

Impact on

casual and permanent employees and owner managers

The impact of imposing trading restrictions to restrict the

transmission of COVID-19 has had a disproportionate impact on casual employees

(or employees without paid leave entitlements). Casual employees account for a

large proportion of all employees working in service industries which were

among the most heavily impacted by the restrictions in terms of employment

loss.[22]

The number of casual employees fell by 339,800 (or 12.9%) between

February and August 2020 while the number of permanent employees (or employees

with paid leave entitlements) fell by 125,600 (or 1.5%) (see table 9).

Impacts have been significant for casual employees working both

full-time (down 160,600 or 18.2%) and part-time (down 179,100 or 10.3%). In

contrast, the number of permanent employees working part-time increased by 107,400

(or 6.7%. However, the number of permanent employees working full-time fell by

233,000 or 3.5%.

Total employees (permanent and casual) working full-time

fell by 393,600 (or 5.2%) between February and August while total part-time

employees fell by 71,800 (or 2.1%).

Table 9: change in permanent and

casual employees, February to August 2020

| Form of employment |

Feb-2020 |

Aug-2020 |

Change —

Feb to August 2020 |

| ‘000 |

‘000 |

000 |

% |

| Employees - full-time |

7 532.1 |

7 138.5 |

-393.6 |

-5.2 |

| Employees - part-time |

3 354.4 |

3 282.6 |

-71.8 |

-2.1 |

| Permanent employees - total |

8 259.3 |

81 33.7 |

-125.6 |

-1.5 |

| Permanent employees - full-time |

6 651.5 |

6 418.5 |

-233.0 |

-3.5 |

| Permanent employees - part-time |

1 607.8 |

17 15.2 |

107.4 |

6.7 |

| Casual employees - total |

2 627.2 |

2 287.4 |

-339.8 |

-12.9 |

| Casual employees - full-time |

880.6 |

720.0 |

-160.6 |

-18.2 |

| Casual employees - part-time |

1 746.5 |

1567.4 |

-179.1 |

-10.3 |

| Total employees |

10 886.5 |

10 421.1 |

-465.4 |

-4.3 |

Source: ABS, Labour Force,

cat. no. 6291.0.55.003, Table 13 (original data)

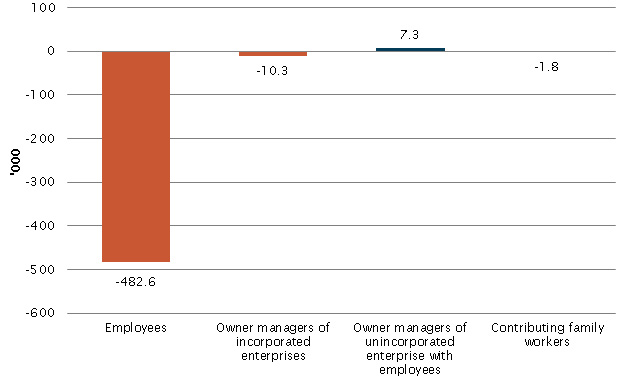

While employees of public and private employers have

experienced a substantial decline in employment between March and August 2020 (down

482,600) there appears to have been little impact on owner managers of

incorporated enterprises (down 10,300), while the number of owner managers of

unincorporated enterprises has grown slightly (up 7,300) (see chart 10).

Owner managers of incorporated enterprises are defined as people

who work in their own incorporated enterprise, that is, a business entity which

is registered as a separate legal entity to its members or owners (may also be

known as a limited liability company). Owner managers of unincorporated

enterprises are people who operate their own unincorporated enterprise or

engage independently in a profession or trade.[23]

Chart 10: change in employees and

owner managers, March to August 2020

Source: ABS, Labour Force,

cat. no. 6291.0.55.003, Table 08 (original data)

Impact on numbers of people

receiving unemployment benefits

Young people were the most heavily affected in terms of

increases in numbers of people receiving unemployment benefits following the

imposition of trading restrictions in March 2020 to combat the spread of

COVID-19. Between March and August 2020:

- The number of people receiving unemployment benefits that were

aged under 25 years and 25 to 34 years more than doubled (up 102.2% and 122.0%

respectively).

- All age groups experienced significant increases in people

receiving unemployment benefits including those in older age groups.

- Men were affected more than women, with a 90.4% increase in men

receiving benefits to 870,143, compared with a 75.7% increase for women to

754,126.

- The total number of Australians receiving JobSeeker Allowance or

Youth Allowance (Other) increased from 886,213 to 1,624,269 (up 808,056 or 83.3%)

(see table 10).

Table 10: JobSeeker Payment and

Youth Allowance (Other) recipients, March and August 2020

| By Age Group |

Females |

Males |

Total |

| March 2020 |

August 2020 |

Change:

March

to

August |

March 2020 |

August 2020 |

Change:

March

to

August |

March 2020 |

August 2020 |

Change:

March

to

August |

| Under 25 |

72 919 |

147 580 |

102.4% |

89 047 |

179 919 |

102.0% |

161 966 |

327 499 |

102.2% |

| 25-34 |

63 062 |

146 930 |

133.0% |

103 021 |

221 705 |

115.2% |

166 083 |

368 635 |

122.0% |

| 35-44 |

79 912 |

137 721 |

72.3% |

87 568 |

166 914 |

90.6% |

167 480 |

304 635 |

81.9% |

| 45-54 |

97 971 |

152 860 |

56.0% |

82 462 |

145 866 |

76.9% |

180 433 |

298 726 |

65.6% |

| 55-64 |

103 038 |

151 714 |

47.2% |

84 008 |

139 494 |

66.0% |

187 046 |

291 208 |

55.7% |

| 65 + |

12 363 |

17 321 |

40.1% |

10 842 |

16 245 |

49.8% |

23 205 |

33 566 |

44.6% |

| Total |

429 265 |

754 126 |

75.7% |

456 948 |

870 143 |

90.4% |

886 213 |

1 624 269 |

83.3% |

Source: Department of Social

Security, JobSeeker Payment and Youth Allowance recipients

– monthly profile.

[1]

ABS, Weekly

Payroll Jobs and Wages in Australia, cat. no. 6160.0.55.001, Methodology.

[2]

ABS, Labour

Force, detailed, cat. no. 6291.0.55.001, Table 01.

[3]

Treasury, Economic Response to the

Coronavirus.

[4]

G Gilfillan, COVID-19:

Impacts on casual workers in Australia—a statistical snapshot, May

2020.

[5]

Deloitte Access Economics, Business Outlook, September

2020, p 130.

[6]

G Gilfillan, Characteristics

and use of casual employees in Australia, January 2018.

[7]

ABS, Labour

Force, Australia, Detailed, cat. no. 6291.0.55.001, Table 8.

[8]

ABS, Weekly

Payroll Jobs and Wages in Australia, cat. no. 6160.0.55.001, Table 3: Industry

spotlight.

[9]

ABS, Weekly

Payroll Jobs and Wages in Australia, cat. no. 6160.0.55.001.

[10]

ABS, Jobs

in Australia, cat no. 6160.0.

[11]

ABS, Labour

Force, cat. no. 6202.0, Table 1.

[12]

People can be underemployed if they are part-time workers seeking

more hours and are available to start, or full-time workers who worked less

hours due to economic reasons such as being stood down.

[13]

ABS, Labour

Force, cat. no. 6202.0, Table 1.

[14]

ABS, Labour

Force, cat. no. 6202.0, Table 19 (Parliamentary Library calculations).

[15]

Economic reasons include a reduction in economic activity or

seasonal highs and lows.

[16]

ABS, Labour

Force, cat. no. 6202.0, Insights into hours worked, September 2020.

[17]

Ibid.

[18]

Ibid.

[19]

Tourism Research Australia, International

Visitor Survey.

[20]

Tourism Research Australia, National

Visitor Survey.

[21]

ABS, Labour

Force, cat. no. 6291.0.55.003, Datacube EQ06.

[22]

G Gilfillan, Characteristics

and use of casual employees in Australia, January 2018.

[23]

ABS, Characteristics

of Employment, cat. no. 6333.0, Glossary.

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

In essence, you are free to copy and communicate this work in its current form for all non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute the work to the author and abide by the other licence terms. The work cannot be adapted or modified in any way. Content from this publication should be attributed in the following way: Author(s), Title of publication, Series Name and No, Publisher, Date.

To the extent that copyright subsists in third party quotes it remains with the original owner and permission may be required to reuse the material.

Inquiries regarding the licence and any use of the publication are welcome to webmanager@aph.gov.au.

This work has been prepared to support the work of the Australian Parliament using information available at the time of production. The views expressed do not reflect an official position of the Parliamentary Library, nor do they constitute professional legal opinion.

Any concerns or complaints should be directed to the Parliamentary Librarian. Parliamentary Library staff are available to discuss the contents of publications with Senators and Members and their staff. To access this service, clients may contact the author or the Library‘s Central Enquiry Point for referral.