30 June 2017

PDF version [PDF 1366KB]

Dr Damon

Muller

Politics and Public

Administration Section

Executive

summary

-

The Coalition, led by Malcolm Turnbull, was returned at the

election with 76 seats and a slim majority of one in the House of

Representatives and faced an enlarged crossbench in the Senate. The 2016

election saw the return of Pauline Hanson’s One Nation, which gained four seats

in the Senate.

- The election followed a double dissolution of the two Houses of

Parliament, only the seventh since Federation, and the first since 1987. The

triggering legislation were the Bills to re-establish the Australian Building

and Construction Commission, which were passed by the Senate after the election

without the need for a joint sitting.

-

The 2016 election was the first to be conducted under the new

Senate voting system, which allowed voters to use optional preferential voting

above or below the line. The changes survived a High Court challenge just prior

to the election. In general, the new Senate system worked as intended, with

voters taking the opportunity to allocate their own preferences.

- The election followed redistributions in the Australian Capital

Territory (ACT), Western Australia (WA) and New South Wales (NSW). The WA redistribution

added a new electorate to the state, and the NSW redistribution removed one,

both of which involved the movement of many voters between divisions.

- Despite the double dissolution triggers being industrial

relations Bills, there was an absence of a fiery campaign on industrial

relations. The eight-week long election campaign brought forth a wide variety

of issues, from milk prices to refugee policy. However, few people would have

guessed at the start of the campaign the importance that Medicare and health

policy would have by election day.

- The campaign featured three leaders’ debates, one of which was

hosted on the social media site Facebook. While campaigns in all 150 seats and

all states doubtless had their own highlights, a number of contests were

notable because of attempted political revivals, escapes from apparently

certain defeat, or the rancour of the battles.

- Despite failures of polling in several recent international

elections, national polls for the federal election closely estimated the

results. Polls for individual divisions were notably less accurate.

-

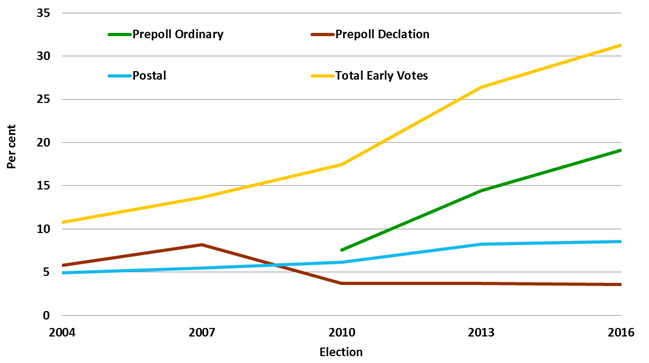

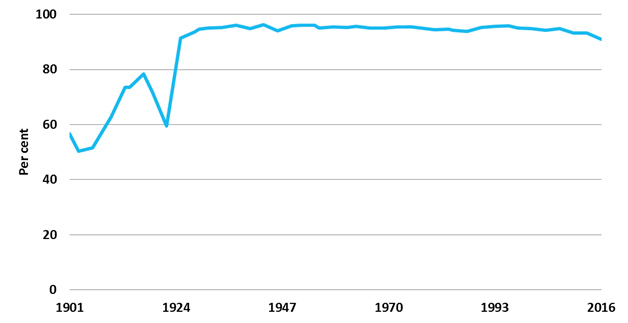

Around one million new voters were added to the electoral roll

for the 2016 federal election, leading to the highest enrolment rate in recent

times—however, the turnout for the election was the lowest since the start of

compulsory voting. Early voting continued to rise, with 4.5 million voters

casting their vote before election day.

- The 45th Parliament first sat on 30 August 2016—113 days, three months

and 21 days after it was dissolved for the election.

Contents

Executive

summary

Introduction

The double dissolution of the

Parliament

The prorogation

Double dissolution triggers

A matter of timing

Redistributions in the ACT, WA and

NSW

ACT

WA

NSW

Polling

The accuracy of the predictions

The results

House of Representatives

The recount in Herbert

Senate

The election campaign

The big issues

Milk prices and dairy farmers

Weekend penalty rates

Parakeelia, entitlements and

donations

Same-sex marriage

Negative gearing and housing

affordability

Asylum seekers and the return of the

boats

The National Broadband Network and

Australian Federal Police raids

‘Mediscare’ and privatising Medicare

The leaders’ debates

Independents: the class of 2010

comeback tour

Micro-parties and preference deals

The Tasmanian Senate race

The fight for Melbourne Ports

Batman returns

Early voting

Electoral participation

Enrolment

Turnout

Informality

The cost of the election

Election advertising

AEC costs

Public funding

Appendix A: Pre-redistribution and

post-redistribution ACT boundaries

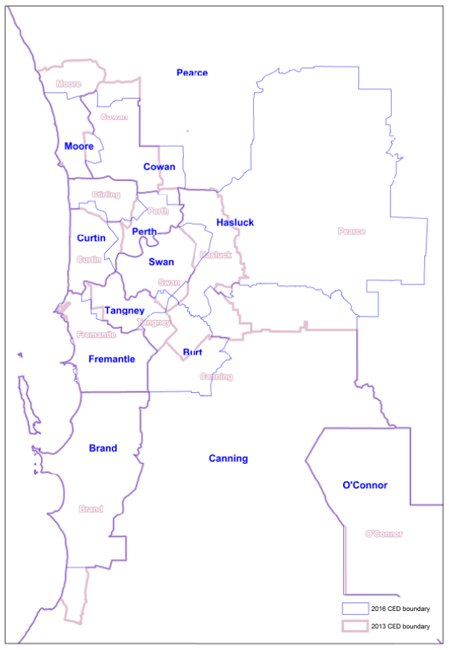

Appendix B: Pre-redistribution and

post-redistribution boundaries for WA

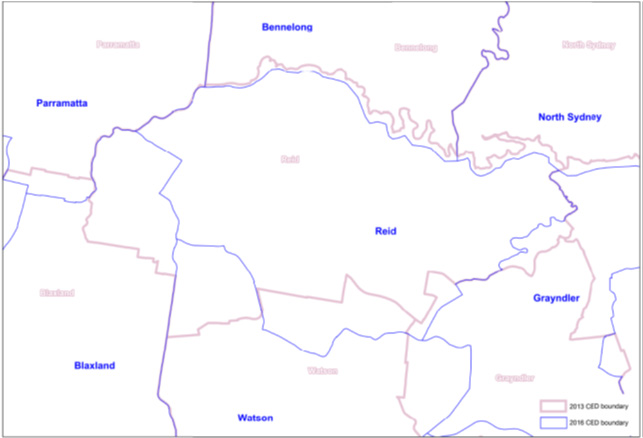

Appendix C: Pre-redistribution and

post-redistribution boundaries in regional NSW

Appendix D: Pre- redistribution and

post-redistribution boundaries in inner Sydney

Appendix E: Election timeline

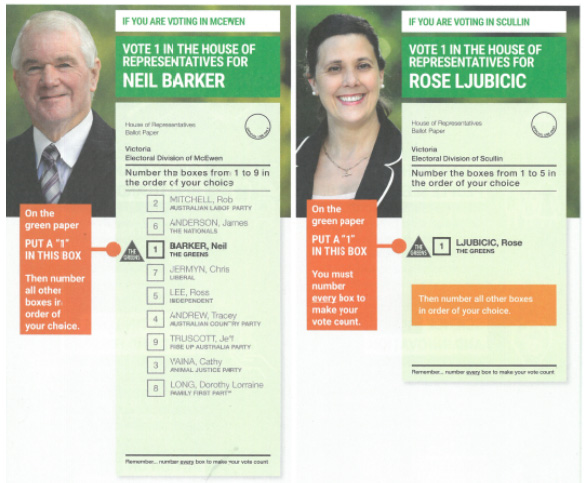

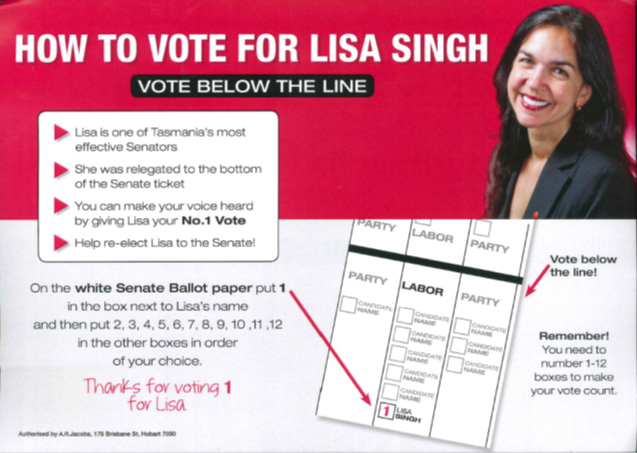

Appendix F: Example of Greens how to

vote cards

Appendix G: Letterboxed flyer from

"Re-Elect Lisa Group" for Tasmanian Senate election

Appendix H: The rotation of Senators

Short and long term senators

The 2016 double dissolution

Appendix I: Enrolment rates

List of Figures

Figure 1: Newspoll results during the

44th Parliament

Figure 2: Two party preferred (TPP)

result nationally and in each state

Figure 3: Percentage of seats won by

each party nationally and in each state

Figure 4: Percentage of first

preference Senate vote by group

Figure 5: Proportion of total Senate

vote by party in 2016 and 2013

Figure 6: Mock Medicare card

Figure 7: Rates of forms of pre-poll

voting at recent federal elections

Figure 8: Turnout rate in Australian

federal elections since Federation

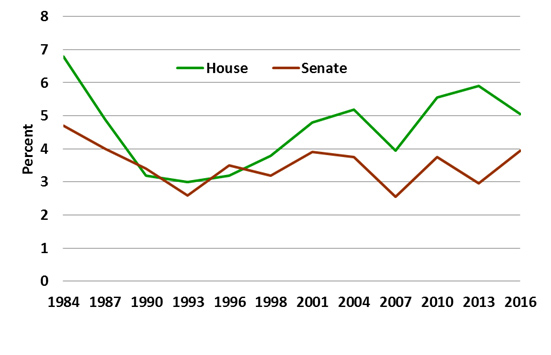

Figure 9: Senate and House informal

voting rate in recent elections

List of Tables

Table 1: Final polls before the 2016

federal election

Table 2: 2013 and 2016 House of

Representatives seats

Table 3: Senate results by state and

party

Table 4: Party composition of the

Senate before and after the election

Table 5: Informal votes from the 2016

election

Table 6: Public funding of political

parties following the 2016 federal election

Table 7: NSW long-term senators under

the two methods

Table 8: Victorian long-term senators

under the two methods

Table 9: Long terms (senators by party

and state)

Table 10: Short terms (senators by

party and state)

Table 11: Enrolment by state, 2016

federal election

Table 12: Enrolment rate by age group,

2016 federal election

Introduction

The 2016 federal election, held on 2 July 2016, saw Malcolm

Turnbull returned as Prime Minister of a Coalition Government with a slim

minority in the House of Representatives.

The election was notable for a number of reasons:

- it was a double dissolution election, only the seventh since

Federation

- the election followed the proroguing of Parliament aimed to focus

the attention of the Senate on the double dissolution triggering legislation

- at roughly eight weeks (55 days), it was the longest election

campaign since the 1969 election campaign, and a little under twice the average

campaign length since then

- the election was conducted following the redistribution of two states—New

South Wales (NSW), which lost a seat, and Western Australia (WA), which gained

one—and a redistribution in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT)

-

the Senate election was conducted under the first significant

change to the Senate electoral system since 1984, and allowed voters to cast as

few as six preferences above the line, and 12 below the line, rather than one

above the line or full preferencing below the line

-

a major party candidate won a Senate seat in Tasmania on the

basis of below the line votes from the bottom position of the party’s ticket

- while the new Senate system was designed, in part, to reduce the

number of micro-parties elected to the Senate, it resulted in the election of

20 crossbench senators, including nine Australian Greens—four from Pauline

Hanson’s One Nation, three from the Nick Xenophon Team, and four others.

The election was unremarkable in the continued increase in

early voting (now constituting 31.3 per cent of all votes, up from 26.4 per

cent in 2013), the continued increase in the non-major party vote in the Senate

(with 26.4 per cent of Senate first preference votes going to someone other than

the Coalition, the Australian Labor Party (ALP) or Greens), and the general

high level of accuracy of Australian political opinion polling.

While the election delivered only a bare majority for the

Coalition in the lower house, and failed to secure a majority in the Senate, it

was, on the whole, relatively trouble free.

The double

dissolution of the Parliament

When the Australian Constitution was written, the

authors realised that there needed to be a way to resolve fundamental disagreements

between the House of Representatives and the Senate over legislation. The

solution was provided in section 57 of the Constitution, which applies

when legislation is passed by the House of Representatives but: the Senate

rejects the legislation; or the Senate fails to pass the legislation; or the

Senate passes the legislation with amendments that are unacceptable to the

House of Representatives. If, after three months or more, the same situation

with the proposed legislation again arises, the legislation becomes a trigger

for a double dissolution of the entire Parliament (the House of Representatives

and the entire Senate).[1]

These Bills are commonly referred to as ‘double dissolution triggers’.

When the requirements of section 57 are fulfilled, the

Governor-General may dissolve both Houses of Parliament (hence a ‘double

dissolution’), leading to a double dissolution election. In a double

dissolution election all 76 Senate seats are declared vacant, along with the

usual 150 seats in the House of Representatives. In practice, the

Governor-General exercises the power to dissolve the Parliament on the advice

of the Prime Minister.

Prior to 2016 there had been six double dissolution

elections—1914, 1951, 1974, 1975, 1983 and 1987. The outcomes of these

elections have been neatly divided between governments being returned to office

(1951, 1974 and 1987) and being defeated (1914, 1975 and 1983). The 1951 double

dissolution election was the only such election where the Government was

returned with a majority in the Senate.[2]

From the point at which Malcolm Turnbull became Prime

Minister on 15 August 2015, after having defeated Tony Abbott for leadership of

the Liberal Party in a party room ballot, the prospect of a double dissolution

was the subject of commentary. Turnbull’s newly-appointed Special Minister of

State, Mal Brough, expressed an intention to legislate reforms to the Senate

voting system.[3]

Commentators noted that the reforms, which appeared likely to reduce the

prospects of micro-party candidates being elected to the Senate, would damage

the Government’s relationship with the crossbench senators elected at the 2013

election.[4]

A double dissolution was seen as an opportunity to implement the reforms and

‘clear out’ the Senate crossbench while giving Turnbull an electoral mandate of

his own and a chance to capitalise on his boost in the polls.[5]

The justification for the double dissolution emerged in

connection with the regulation of trade unions following the report of the

Royal Commission into Trade Union Governance and Corruption (Trade Union Royal

Commission or TURC), which was delivered in December 2015.[6]

In October 2015 Turnbull had flagged the possibility of industrial relations laws

to reintroduce the Australian Building and Construction Commission (ABCC)—that

had stalled in the Senate—becoming a double dissolution trigger if they were

not passed by Parliament.[7]

In mid-December 2015 media reports stated that several

cabinet ministers were urging Turnbull to call an election early in 2016; these

reports also highlighted issues around the timing of the budget, planned for 10 May 2016.

Further, according to one journalist, Turnbull was ‘worried the required double

dissolution would leave him hostage to an even more unmanageable Senate

crossbench than the gaggle likened to the Mos Eisley cantina from Star Wars.’[8]

The Government scheduled the reintroduction of the ABCC Bills[9]

for the beginning of the parliamentary year, signalling the potential for a

double dissolution if the legislation was not passed.[10]

The prorogation

In defiance of the Government’s agenda, the Senate declined

to immediately consider the ABCC Bills when it reconvened for the 2016 parliamentary

year. Upon receiving the ABCC Bills from the House on 4 February 2016, the

Senate voted to refer the Bills to the Education and Employment Legislation

Committee for reporting on 15 March 2016,[11]

two days before Parliament rose for seven weeks.[12]

This effectively meant that the Senate was unlikely to consider the Bills

before it adjourned for the seven week break, complicating the timeframe for calling

a double dissolution election.[13]

As the Senate is able to choose its own sitting calendar,

and the Government was without a majority in the Senate, the Prime Minister

took the unusual step of advising the Governor-General to prorogue the

Parliament on 15 April and summon it to meet again on 18 April 2016, which duly

took place.[14]

Proroguing a parliament ends its current session but without necessarily

leading to an election. After prorogation a parliament can be recalled by the

Governor-General to sit again on a specified date.

This was the first prorogation and commencement of a new

session prior to an election in almost 40 years.[15]

However, as the Attorney-General’s advice to the Governor-General noted, it was

not unprecedented, with the Parliament having been prorogued in 1914 with the

express purpose of bringing back the Senate to consider Bills that were double

dissolution triggers.[16]

The Senate elected to consider the Prime Minister’s

nominated Bills upon the day of its return, negativing both the ABCC Bills at

6.23pm (as the Registered Organisations Bill was already a trigger it was not

again considered by the Senate).[17]

The next day, on 19 April 2016, the Prime Minister announced that he would be

seeking a dissolution of both Houses from the Governor-General, and nominated

his preferred election date of 2 July 2016.[18]

Double

dissolution triggers

The three Bills that were listed in the proclamation[19]

dissolving both Houses of Parliament were the:

- Building and Construction Industry (Consequential and

Transitional Provisions) Bill 2013 [No. 2][20]

- Building and Construction Industry (Improving Productivity) Bill

2013 [No. 2][21]

and

- Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Amendment Bill 2014 [No. 2].[22]

A matter of

timing

The timing of any election is dependent on the requirements

of both the Constitution and the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918

(CEA).[23]

In the case of the 2016 double dissolution election, timing was particularly

important for reasons of both law and political practicality.

Section 57 of the Constitution, the section under

which the Governor-General dissolved both Houses of Parliament, states that the

simultaneous dissolution ‘shall not take place within six months before the

expiry of the House of Representatives by effluxion of time’.[24]

Section 28 of the Constitution requires that ‘the House of

Representatives shall continue for three years from the first meeting of the

House, and no longer’.[25]

The 44th Parliament commenced on 12 November 2013, meaning

that it would have expired on 11 November 2016 if the House of

Representatives had run its full term. As such, under section 57, the last

possible day that a simultaneous dissolution could be held was 11 May 2016.

In the Senate, the terms of senators are staggered. In a

normal half-Senate election, half of the senators for the states will be up for

election—they will then serve fixed six-year terms. In the normal course of

elections half of the 12 senators for each state are elected every three years,

with their terms commencing on the following 1 July. In a double

dissolution election, however, all Senate places are up for election and,

following such an election, the terms of the senators elected are back-dated to

commence on the 1 July prior to the election.[26]

Following a double dissolution election the staggering of Senate terms is

preserved by the Senate dividing the elected senators from the states into two

groups, with one group being awarded full six-year terms and one group being

awarded three-year terms. More detail on the rotation of senators is set out at

Appendix H.

If the double dissolution election had been held prior to 1 July 2016,

the terms of the senators elected would have been back-dated to 1 July 2015.

This would have meant that those senators with the shorter three-year terms

would have concluded their terms on 30 June 2018, necessitating a

half-Senate election well before then. This would have necessitated the Government

either holding a normal general election around two years into its term, or

holding a separate half-Senate election and then a House of

Representatives election a year or so later.

The Constitution requires that writs for election to

the Senate and the House of Representatives must be issued within 10 days of

the dissolution of Parliament (sections 12 and 32 respectively).[27]

However, the remainder of the details of the conduct of elections are contained

within the CEA. The combination of flexibility in the timing of the

issue of the writs (within 10 days) and the election timetable in the CEA

allows a maximum of 68 days between the dissolution of Parliament and election

day. A dissolution of Parliament on 11 May 2016 would, therefore, have

allowed an election up to Saturday 16 July. This potentially meant that a

post-1 July 2016 double dissolution election was possible in order to

maximise the terms of the senators elected by having their terms commence on

the 1 July prior to the election (that is, 1 July 2016) rather

than 1 July 2015.

Complicating matters, 10 May 2016 was the day

scheduled for the release of the 2016 Budget. While it was technically possible

for the Government to deliver its budget and then to advise the

Governor-General to dissolve both Houses of Parliament immediately afterwards, this

would have been logistically and politically difficult. The Prime Minister resolved

the issue by moving the Budget forward by one week to 3 May, and then

announced on Sunday 8 May that the 2016 federal election would be held on 2 July 2016.[28]

While the writs for an election are typically issued on the

day that the election is announced (or shortly thereafter) as noted above,

section 32 of the Constitution specifies that the writs for an election

must be issued within 10 days of the proclamation of the dissolution of

Parliament.[29]

Due to the unusually long election period, the Government chose to have the

writs issued on 16 May 2016, one week after both Houses were

dissolved.[30]

Counted from the dissolution of both Houses, the total

election period was 54 days (seven weeks and five days). A detailed timeline is

set out in Appendix E.

Redistributions in the ACT, WA and NSW

The 2016 federal election was held on new boundaries due to

redistributions of NSW, WA and the ACT during the 44th Parliament. While the

ACT had only a relatively minor change in boundary (and the renaming of one of

its two divisions), Western Australia gained one electorate and NSW lost one

electorate.

Both the ACT and the Northern Territory (NT) were due for

redistributions in the 44th Parliament due to the expiration of seven years

since their last redistribution. The NT redistribution commenced on 15 October 2015,

but was not completed before the election so the election was held under the

existing boundaries.[31]

A year after the Parliament first sits, an entitlement

determination is made calculating how many seats each state and territory is

entitled to in the House of Representatives. A formula is applied to the Australian

population and the population of each state and territory to determine the

entitlement to seats in each state and territory. During the 44th Parliament the

entitlement determination made on 13 November 2014 determined that

NSW was entitled to 47 seats (one fewer than in 2013) and WA was entitled to 16

seats (one more than in 2013).[32]

Complicating matters somewhat was the talk of an early

election following Malcolm Turnbull taking the leadership of the Liberal Party

in September 2015. Section 76 of the CEA requires that, if an

election is called when a redistribution is underway, and the entitlement of a

state has changed, the Electoral Commissioner must undertake a

‘mini-redistribution’.

Under a mini-redistribution, if a state is to lose a division,

the two adjacent divisions with the smallest combined population are combined

into one new division. If a state is to gain a division, the two adjacent

divisions with the highest combined populations are split into three new

divisions with the same number of electors. This must happen between the issue

of the writs and the close of nominations (between 10 and 37 days after the

election is announced). A mini-redistribution would likely have thrown the

party pre-selections and nominations into chaos—and the mechanism has never

actually been used since it was introduced into the CEA in 1983.[33]

ACT

The 2014 entitlement determination found that the ACT was

still entitled to the two seats in the House of Representatives, but that the

current boundaries did not meet the current and projected enrolment quotas.[34]

The redistribution expanded the size of the ACT’s southern

division (Canberra) by moving its boundary to the north. This boundary change

resulted in 10,226 electors, or 3.79 per cent of enrolled electors, moving

division.[35]

Both divisions remained notionally Labor seats. Maps of the new boundaries are at

Appendix A.

The redistribution also changed the name of the northern ACT

seat, held by Labor’s Dr Andrew Leigh, from the division of Fraser to the

division of Fenner. The division was originally named after John Fraser, a

member of the House of Representatives for the ACT from 1951 to 1970. It was

decided to retire the name of Fraser to provide the option of naming a

Victorian division Fraser in the future in honour of former Prime Minister

Malcolm Fraser, who died in 2015.[36]

WA

The 2014 entitlement determination found that the population

of Western Australia had increased sufficiently for WA to increase its entitlement

from 15 to 16 seats.[37]

The resulting WA redistribution commenced on 1 December 2014 and the

proposed new boundaries were announced on 21 August 2015. The

proposed boundaries were accepted with only minor changes on 5 November 2015.

Maps of the new boundaries are in Appendix B.

A new division was created south of Perth, mainly out of

the existing divisions of Canning and Hasluck, with parts of Swan and Tangney.

The redistribution involved the movement of 264,401 electors, or six per cent

of the WA electorate, including 93,763 moving into the new division.[38]

The new division was named Burt, honouring multiple

generations of the Burt family ‘for their significant contributions to the

justice system and for their wider contributions to public service’.[39]

The new division of Burt was notionally marginally Liberal based on 2013 federal

election results. The notional two party preferred vote for the remaining 15

seats did not change, nor did the names of the divisions.[40]

Although it occurred after the proposed boundaries were

released, the Canning by-election, held on 19 September 2015

following the death of sitting Liberal member Don Randall, was held on the

original boundaries.[41]

NSW

The NSW redistribution was the most contentious of the

three, with the requirement that one division be removed and, as a result, one

sitting member potentially losing their seat. The redistribution took NSW from

48 to a new total of 47 seats.

The Redistribution Committee abolished the seat of Hunter on

the NSW North Coast, however, the neighbouring seat of Charlton was expanded to

take in most of the area and above fifty per cent of the voters who had

previously been in Hunter. Charlton was then renamed to Hunter, with the net

effect being that Charlton was essentially abolished. While the Redistribution

Committee explained that Hunter was a Federation seat,[42]

and the naming guidelines for electoral divisions encourage the retention of

Federation names, it is not clear why the Committee choose to go about the

redistribution in such a confusing and circuitous manner.[43]

Both Hunter and Charlton were held by Labor members Joel Fitzgibbon and Pat

Conroy, respectively.

Following the death of former Prime Minister Gough Whitlam in

2014 it was decided that the division of Throsby (NSW) be renamed to Whitlam.

The Committee conceded that Throsby had no direct connection to the former

Prime Minister, but of the five divisions in contention to potentially be

renamed Whitlam, two were already named after Prime Ministers (Hughes and

McMahon (both NSW)), one was a Federation division (Werriwa (NSW)) and one was

only one of four NSW divisions named after a woman (Fowler (NSW)). Only Throsby

remained, and so it was renamed to Whitlam.[44]

The proposed redistribution released in October 2015 was a

substantial change to the status quo, with almost 20 per cent of NSW

voters, or just under a million electors, moving division. The proposal drew

791 objections and resulted in two inquiries into the objections, which were

held in December 2015.

Some of the most debated proposed boundary movements were in

inner Sydney, mostly in seats held by Labor where there was a growing Australian

Greens vote. The proposed changes to the inner-Sydney seats of Barton and

Grayndler were mostly abandoned when the final boundaries were released. The

ALP member for Grayndler, Anthony Albanese, considered nominating for the safer

neighbouring seat of Barton. Albanese is quoted as saying that the risk of losing

the seat to the Greens was a primary reason for him remaining to contest it

again.[45]

The final boundaries were released in February 2016 and

resulted in 18.91 per cent, or 919,914 electors, moving divisions (excluding

those in the division of Throsby, which was renamed to Whitlam).[46]

Maps of the boundaries are at Appendix C (regional) and Appendix D (Sydney

area).

Of the 47 post-redistribution divisions, the new division of

Hunter was notionally Labor, along with 19 other divisions, up from 18 Labor

divisions pre-redistribution. Post-redistribution, 20 seats were notionally

Liberal, down from 23, and an unchanged seven were notionally National. Overall,

Labor notionally increased its seat tally by two seats, and the Liberal Party notionally

decreased its tally by three seats.[47]

Polling

Australian federal politics’ fascination with polling

continued through the 44th Parliament. When Malcolm Turnbull announced that he

was challenging Tony Abbott for leadership of the Liberal Party, he stressed that

the Liberal Party’s polling presaged defeat in the next election:

Now if we continue with Mr Abbott as Prime Minister, it is

clear enough what will happen. He will cease to be Prime Minister and he will

be succeeded by Mr Shorten ... The one thing that is clear about our current

situation is the trajectory. We have lost 30 Newspolls in a row. It is clear

that the people have made up their mind about Mr Abbott’s leadership.[48]

Commentator Michelle Grattan noted that polls were central

to the removal of Kevin Rudd, Julia Gillard and Tony Abbott. She observed that

parties are ‘increasingly unwilling to tolerate leaders who, even if only in

the short term, look like losers’.[49]

If a change in the 30 Newspoll run was one of the

objectives of the leadership change, it was successful, with the pre-change 7 September

2015 Newspoll showing the Coalition on a two party preferred (TPP) vote of 46

and the first post-leadership change Newspoll on 21 September giving the

Coalition a TPP of 51. While the Coalition managed to get its TPP to 53 per

cent for late 2015 and early 2016, it fluctuated between 51 and 49 in the lead

up to the election. The Newspoll boost in primary vote for the Coalition

surpassed Labor by 9 points following the leadership change, and did not fall

below Labor’s primary for the remainder of the term (Figure 1).

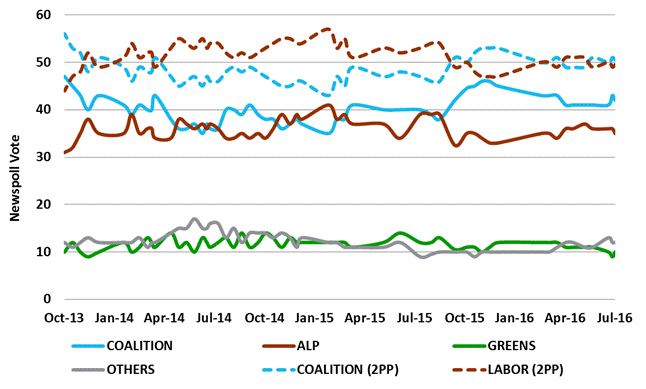

Figure 1: Newspoll results

during the 44th Parliament

Source: Compiled by Parliamentary Library from Newspoll data.

Four weeks out from the election, Ipsos (the new polling

company used by the Fairfax newspapers) was reporting that Labor was leading 51

to 49 per cent in TPP terms. This reversed a Coalition TPP lead by one point

two weeks prior. Reporting the poll, journalist Phillip Coorey concluded that

the election was at that point ‘too close to call’.[50]

If the close polling numbers carried over to a win by the Coalition with a

narrow majority, this was expected to only heighten the poll-sensitivity of the

Coalition party-room and increase the precariousness of the leadership position

in the new term.[51]

As the election drew near, Newspoll was showing the

Coalition and Labor both with a TPP of 50 per cent two weeks from polling day,

with Turnbull’s net satisfaction rating of minus 15 points just slightly

ahead of Shorten’s rating of minus 16 points. Only in the preferred prime

minister rating did Turnbull maintain a reasonable lead, with 46 per cent over

31 per cent for Shorten.[52]

The Prime Minister’s dip in popularity carried through to his own electorate,

with a poll commissioned by the ALP candidate for the seat of Wentworth (NSW)

showing a 10 per cent swing against Turnbull (the seat would have been

comfortably retained by the Prime Minister nonetheless).[53]

Despite the closeness of the polls it was widely expected

that the Coalition would win—the close polls only indicating that it would not

win by much. Crikey polling analyst William Bowe explained that while

Labor might win half of the votes (in TPP terms), that was unlikely to win it

the majority of the seats as the increases in support that Labor was recording

were located in the wrong areas to gain it enough seats. Of particular note was

Queensland, where the Coalition held ten seats on margins of 7 per cent or

less, but where polls were recording swings against the ALP.[54]

The final polls prior to the election are in Table 1.

Table

1: Final polls before the 2016 federal election

| Poll |

Date |

n |

Coalition |

ALP |

Greens |

Others |

Coalition

TPP |

Labor

TPP |

| Essential |

1/07/2016 |

1212 |

42 |

34.5 |

11.5 |

10.5 |

50.5 |

49.5 |

| Galaxy |

5/06/2016 |

1867 |

40 |

35 |

10 |

15 |

50 |

50 |

| IPSOS |

16/06/2016 |

1437 |

39 |

33 |

14 |

14 |

51 |

49 |

| Newspoll |

2/07/2016 |

4135 |

42 |

35 |

10 |

12 |

50.5 |

49.5 |

| ReachTel |

30/06/2016 |

2084 |

- |

34.6 |

10.7 |

10.5 |

51 |

49 |

Source: Compiled by Parliamentary Library from various sources.

The

accuracy of the predictions

The accuracy of the pollsters has been analysed by a number

of sources, including by polling company ReachTel, who were pleased to report

that it was ‘accurate to less than a single percentage point’ for its TPP

results.[55]

In fact, all of the final polls from the major polling companies came to within

one percentage point of the final TPP result, with Essential and Newspoll

coming within 0.1 percentage point of the final result.[56]

Newspoll had each of the major party primary votes to within 0.3 percentage

points of their actual result.[57]

The 2016 federal election also featured the results of a

large amount of polling of individual electorates being released into the

public sphere. An analysis by William Bowe of Crikey suggests that electorate

polls performed relatively poorly, although in a relatively consistent way.

Bowe reports that, while the seat polls conducted by ReachTel and Galaxy had

samples of around 600 respondents (which would have resulted in a margin of

error of around 4 per cent), they behaved as if their margin of error

was 7 per cent, and skewed 1.3 per cent in favour of the Coalition.

One effect of this was that they did a poor job of predicting swings to Labor,

such as the swings in Macarthur in Sydney and the state-wide swings in

Tasmania.[58]

Bowe also points out that at least 19 polls were released

prior to the election that had been commissioned from ReachTel by private

clients, most of which were left-of-centre unions or lobby groups. These polls

tended to show a TPP bias towards the ALP—however, Bowe speculates that this

might be due to selection bias (commissioned polls only being released if they

fit the narrative of the organisation that commissions them).[59]

Given the significant failures of polling in recent

elections in other, similar, western democracies (such as the United Kingdom

(UK) in 2015 and the United States in 2016), there is a question as to why the

national polling in Australia continues to be so accurate. The increasing

number of households without landlines was thought to undermine the

representativeness of political polling, however, the one Australian polling

company that still uses live phone calls, Ipsos, was substantially less

accurate than those who use robopolling (automated phone calls) and online

panels, such as ReachTel and Newspoll.[60]

It may be that Australia’s compulsory voting is one of the

reasons that polling still works for Australian elections. A review of the

failure of the polls at the 2015 UK general election found that three groups

were underrepresented in the polling: older voters, who predominately voted

Tory; young non-voters, who were polled less frequently than young people who did

intend to vote; and busy voters, who were more likely to vote Tory.[61]

Compulsory voting means that Australian polling has much

firmer grounds for extrapolating from demographic sub-samples. As long as some

older people respond to an online poll, and those people are reasonably

representative of the views of older people, it is not difficult to extrapolate

to the wider voting population with a degree of accuracy. Sophisticated turnout

models to determine which demographics will vote are not necessary. Polling

experts also note that the Telemarketing and Research Industry Standard, which

allows polling companies to contact numbers on the Do Not Call Register if the

polling is for research purposes, also adds to the accuracy of Australian

polling.[62]

If turnout continues to fall (as discussed on page 30), the accuracy of polling in Australia may also be affected. However, in the immediate

future, it appears that Australian polling companies have adapted well to the

changing polling environment.

The results

The Coalition, led by Malcolm Turnbull, was returned to

Government at the election with a slim majority of 76 seats in the House of

Representatives and faced an enlarged crossbench in the Senate. The 45th

Parliament first sat on 30 August 2016, 117 days, 3 months and 25 days after the

44th Parliament was dissolved for the election.

House of

Representatives

The Coalition was returned to Government with 76 seats in

the 150 seat Parliament, and 50.4 per cent of the TPP vote (Figure 2). The ALP

won 69 seats, and Katter’s Australian Party and the Greens each retained their

one seat, as did two independents (Cathy McGowan and Andrew Wilkie). The Nick

Xenophon Team won one seat from the Coalition.

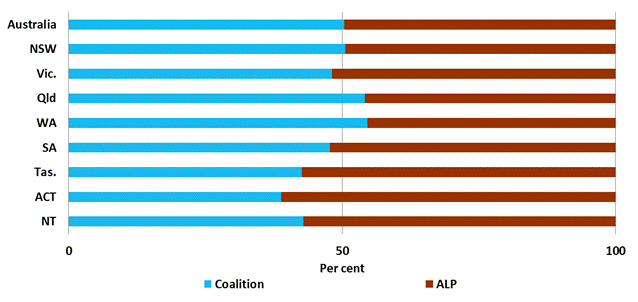

Figure 2: Two party preferred

(TPP) result nationally and in each state

Source: Compiled by the Parliamentary Library from AEC election

results data.

The 2016 election resulted in a net loss of 14 seats by the

Coalition, and a notional TPP swing of 3.13 percentage points against the

Coalition (Table 2).[63]

In national first preference terms, the highest swing was against the Liberal

party (-3.35 percentage points), with a small swing towards the Nationals (0.32

percentage points). Labor (1.35 percentage points), the Greens (1.58 percentage

points) and the Nick Xenophon Team (1.85 percentage points) recorded small

swings towards them in the House of Representatives elections.

Table 2: 2013 and 2016 House

of Representatives seats

| Party |

2013 |

2016 |

Change |

| Coalition |

90 |

76 |

-14 |

| Australian Labor Party |

55 |

69 |

+14 |

| Independent |

2 |

2 |

0 |

| Katter's Australian Party |

1 |

1 |

0 |

| The Greens |

1 |

1 |

0 |

| Palmer United Party |

1 |

– |

-1 |

| Nick Xenophon Team |

– |

1 |

+1 |

Source: Compiled by the Parliamentary Library from AEC election

results data.

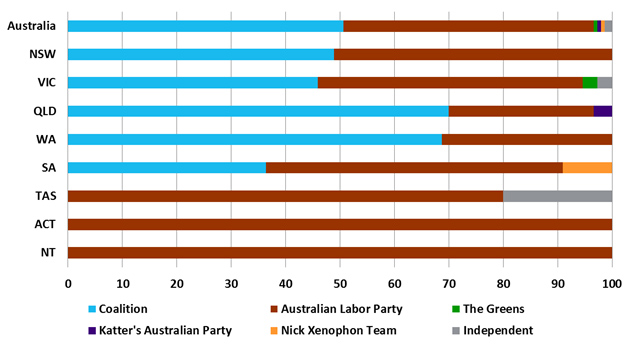

Figure 3: Percentage of seats

won by each party nationally and in each state

Source: Compiled by the Parliamentary Library from AEC election

results data.

Compared at a state-by-state level, Labor was more

successful than the Coalition in terms of both TPP vote and seats won in

Victoria, South Australia, Tasmania and the two territories. Although the Coalition

won more than half of the TPP in NSW (50.53 per cent), it won less than half of

the seats (23 of 47). See Figure 3 for details.

Of the 19 seats that changed hands following the election (see

Appendix J), 15 were won by Labor from the Coalition, and two were won by the

Coalition—one from Labor (Chisholm in Victoria) and one from the Palmer United

Party (Fairfax in Queensland). One seat, Murray (Vic.), was won by the

Nationals from the Liberals where the sitting Liberal member did not recontest

the seat. The Nick Xenophon Team won their first lower house seat (Mayo, SA) from

the Liberals.

A total of 17 of the 150 seats were what the Australian Electoral

Commission (AEC) refers to as ‘non-classic’ divisions, where the final contest

is not between a Labor and a Coalition candidate. This was up from 11 ‘non-classic’

divisions in 2013.

A notable feature of the 2016 election was the number of

seats where a Greens candidate finished in second place. Six ‘non-classic’

contests were between the Greens and either Labor (Batman, Wills (both Vic.)

and Grayndler (NSW)) or the Liberals (Higgins, Melbourne (both Vic.) and Warringah

(NSW)), with a Greens victory only in their existing House of Representatives seat

of Melbourne. While these tended to be the Greens’ best-performing seats (with

the exception of Warringah, which was the Greens 35th best seat, in terms of

percentage of primary vote), in none of the contests that the Greens lost was

the two candidate preferred margin particularly close.

Interestingly, in the Greens fifth best seat in terms of

first preference votes (Melbourne Ports (Vic.)), the Greens were not one of the

final two parties in the count. Melbourne Ports is also notable for having the

lowest primary vote of a winning candidate in the election (27.0 per cent).

With the exception of Herbert (Qld), where the post-recount

two candidate preferred margin was 37 votes, none of the seats were

particularly close by the final count, with the remaining 149 seats having a

two candidate preferred margin of 1,000 votes or more.

The recount

in Herbert

The initial count in the division of Herbert was closely

watched as the margin teetered from the ALP to the Liberal National Party (LNP)

and back again by a handful of votes. So closely scrutinised was the count that

the Attorney-General, Senator Brandis, was lending his support as a scrutineer.[64]

As the recount progressed, the LNP was beginning to lay

plans to challenge the result in the Court of Disputed Returns amongst

allegations that some voters were not able to vote in the division due to AEC

errors.[65]

Soldiers from Townsville had reported that they were unable to cast absent

ballots in South Australia due to the polling places they attended not having

ballot papers for Herbert, and staff at a Townsville hospital reported that 39

patients on one ward were not provided ballot papers.[66]

In mid-September the LNP announced that it had failed to

gather sufficient evidence to take the Herbert count to the Court of Disputed

Returns to appeal the result. Thirty people at the hospital were prepared to

sign declarations that they had not been able to vote, eight fewer than would

have been needed to challenge the result.[67]

The seat remained an ALP gain by a margin of 37 votes.

Senate

Prior to the election the Senate voting system was changed

to allow voters to either vote above the line by numbering six or more

preferences for groups of candidates, or vote below the line by numbering 12 or

more preferences for individual candidates. This removed the use of group

voting tickets which had been in place since 1984. The history and effects of

this change will be discussed in detail in a forthcoming Parliamentary Library

publication.

Following the election of all senators, the returned Senate

comprised 30 Coalition senators out of the total 76; 26 ALP senators; nine

Greens; four Pauline Hanson’s One Nation senators; three Nick Xenophon Team

(NXT) senators and four others (see Table 3).

Table 3: Senate results by

state and party

| Party |

NSW |

Vic. |

Qld |

WA |

SA |

Tas. |

ACT |

NT |

Total |

| Australian Labor Party |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

5 |

1 |

1 |

26 |

| Liberals |

3 |

4 |

|

5 |

4 |

4 |

1 |

1 |

22 |

| LNP Queensland |

|

|

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

| The Nationals |

2 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

| Coalition Total |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

4 |

4 |

1 |

1 |

30 |

| The Greens |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

|

|

9 |

| Pauline Hanson's One Nation |

1 |

|

2 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

4 |

| Derryn Hinch's Justice Party |

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

| Family First |

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

1 |

| Jacqui Lambie Network |

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

1 |

| Liberal Democrats |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

| Nick Xenophon Team |

|

|

|

|

3 |

|

|

|

3 |

| Total |

12 |

12 |

12 |

12 |

12 |

12 |

2 |

2 |

76 |

Source: AEC, ‘Senate

party representation’, 2016 Federal Election, AEC Tally Room website, 9

August 2016.

Following the election the Senate had three fewer Coalition

senators, one more Labor senator and one fewer Greens senator than previously.

If one objective of the election was to diminish the Senate crossbench it was

unsuccessful at doing so, with four crossbench senators returned (Nick Xenophon

of NXT, David Leyonhjelm of the Liberal Democrats, Jacqui Lambie of the Jacqui

Lambie Network and Bob Day from Family First) and an additional seven

non-Greens crossbench senators elected (four from Pauline Hanson’s One Nation,

two from NXT and one from Derryn Hinch’s Justice Party).

With 20 crossbench Senators (9 Greens and 11 others), the

post-election Senate crossbench in the 45th Parliament was the largest since

Federation (it has since grown to 21 senators). The previous largest Senate

crossbench was 18 in the previous Parliament (10 Greens and eight others), and

prior to that 13 senators from 2002 to 2005.[68]

Table 4: Party composition of

the Senate before and after the election

| Party |

44th Parliament |

45th Parliament

(post-election) |

| Coalition |

33 |

30 |

| Australian Labor Party |

25 |

26 |

| Australian Greens |

10 |

9 |

| One Nation |

- |

4 |

| Nick Xenophon Team |

1 |

3 |

| Liberal Democrats |

1 |

1 |

| Family First |

1 |

1 |

| Jacqui Lambie Network |

1 |

1 |

| Derryn Hinch's Justice Party |

- |

1 |

| Independents |

2 |

- |

| Palmer United Party |

1 |

- |

| Australian Motoring Enthusiast Party |

1 |

- |

Source: Australian Senate website[69]

Following the election, for the Government to pass

legislation through the Senate opposed by Labor and the Greens (with 35 seats

between them), it required at least nine votes from other 11 crossbench

senators to gain a majority of 39 votes (see Table 4).[70]

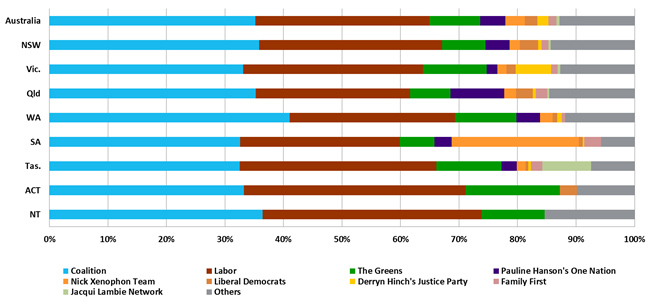

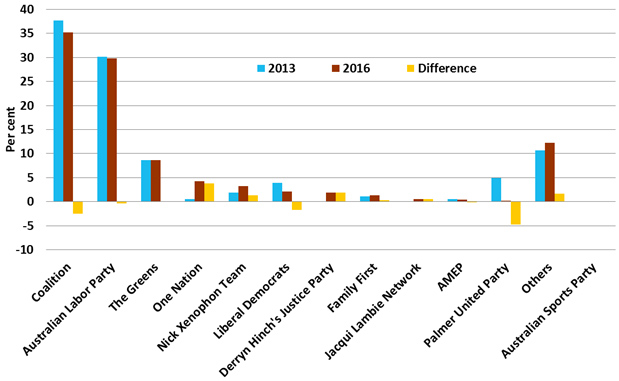

Figure 4: Percentage of first

preference Senate vote by group

Source: Compiled by the Parliamentary Library from AEC election

results data.

Compared to 2013, the primary vote in the Senate of the

major parties decreased, and most of the successful minor parties saw an

increase in their vote share. The notable exceptions were the Liberal

Democrats, who might have seen a vote reduction due to not gaining the first

column on the NSW ballot paper as they did in 2013, and the Palmer United

Party, which did not run a large advertising campaign as it did in 2013. The

Greens received an almost identical proportion of the total vote across the two

elections.

Figure 5: Proportion of total

Senate vote by party in 2016 and 2013

Source: Compiled by the Parliamentary Library from AEC election

results data.

The

election campaign

The eight week election campaign covered a large number of

issues, the most salient of which are discussed below. It also featured three

leaders’ debates, one of which was hosted on the Facebook social media site.

And, while campaigns in all 150 seats and all states doubtless had their own

highlights, a number of contests were notable because of attempted political

revivals, escapes from apparently certain defeat, or simply due to the rancour

of the battles.

The big

issues

Industrial relations was flagged as a likely key election

issue well before the campaign;[71]

however, despite the Prime Minister’s statement that the ABCC and Registered

Organisations Bills ‘represent important elements of the Government’s economic

plan for jobs and growth, and of its reform agenda’,[72]

the industrial relations debate played only a minor role in the election campaign.

Media commentators speculated that, in the absence of actual industrial chaos

in recent times, industrial relations as an election topic was not of

particular interest to voters, and not a focus for the Prime Minister.[73]

Despite the absence of a fiery campaign on industrial

relations, the long election campaign brought forth a wide variety of issues,

from milk prices to refugee policy. However, few people would have guessed at

the start of the campaign that health policy would assume the importance it did

by election day.

Milk prices

and dairy farmers

One of the early issues to arise in the campaign was the

price of milk, albeit not in the form of the perennial ‘gotcha’ question of

knowing the price of a litre. Two large dairy processors, Murray Goulburn and

Fonterra, announced in early May 2016 that they were reducing the amount paid

to farmers for milk due to over-estimating returns from exports.[74]

Farmers proposed a $0.50 levy on fresh milk sales to support

the industry, and the Greens suggested that a floor price for milk be

considered.[75]

The Coalition and Labor both rejected the idea of a levy, with the Agriculture

Minister, Barnaby Joyce, announcing an assistance package for Murray Goulburn

and Fonterra suppliers worth $555 million.[76]

While the Government claimed that the assistance package,

which was announced in the pre-election ‘caretaker’ period, followed

consultation with the Opposition, Opposition agriculture spokesperson, Joel

Fitzgibbon, stated that the Opposition had received only a ‘vague letter’.

Labor announced that it supported the assistance package but believed it to be

inadequate.[77]

As much as it achieved prominence at the beginning of the

campaign, by the end of May the topic of milk prices had effectively

disappeared from the mainstream campaign coverage.

Weekend

penalty rates

The Fair Work Commission (FWC) was expected to rule on

penalty rates in seven awards in the retail and hospitality sector by July 2017.[78]

While the union movement campaigned to have penalty rates retained, noting how

important they were for working people to survive financially, employer groups

wanted Sunday and public holiday penalty rates reduced.

Both the Government and Labor said that they would leave

decisions on penalty rates to the Commission; however, Labor stated that, if it

won the election, it would make a submission to the FWC in support of retaining

existing penalty rates.[79]

The Greens stated that they would legislate a floor rate for penalty rates so

that the FWC could not reduce them beyond a certain level.[80]

The approach of the Greens was supported by unions, such as the Australian

Manufacturing Workers Union and the Electrical Trades Union, which implicitly

criticised Labor for failing to do enough to protect penalty rates.[81]

Labor settled on a position of arguing that it did not

believe that the FWC would cut penalty rates, and stated it would consider

inserting a ‘no reduction’ principle into the Fair Work Act.[82]

During the third leaders’ debate, the Prime Minister committed to abide by the

decision of the FCW regarding penalty rates, and would not change them.[83]

The FWC finally handed down its decision to reduce Sunday

penalty rates for retail and hospitality employees on 23 February 2017.[84]

Parakeelia, entitlements and donations

Parakeelia Pty Ltd is a software company owned by the

Liberal Party that maintains a software platform called Feedback. The ALP has a

similar software platform called Campaign Central, developed by Magenta Linas

Software.[85]

A media report explains the functions of these software packages and their

utility to their respective parties:

The software works by uploading electoral [roll] data from

the Australian Electoral Commission, and allows MPs and their campaign teams to

log in and add in relevant information about their dealings with individuals in

their electorate. This is then mined for intelligence and used to determine

which issues are relevant in different seats, and mobilise support in

marginals.[86]

Contributions from Parakeelia to the Liberal Party were

raised in advance of the election. These included in-kind contributions, such as

renting the premises for the Liberal national headquarters at the 2013 federal

election (apparently using money the Liberal Party paid to Parakeelia for that

purpose)[87]

and cash contributions of more than $1.3 million over several years.[88]

The payment of money from Liberal Party MP office

entitlements to Parakeelia was perceived by some as a way of funnelling money

from the entitlements (which are not supposed to be used for campaigning) back

into the party coffers where it could be used for political campaigning.[89]

It was reported that Parakeelia was the ‘second biggest source of income’ for

the Liberal Party’.[90]

It was never conclusively established that the arrangement

between Parakeelia and the Liberals was in breach of the entitlements rules or

the CEA, and the issue, ultimately, only led to some discussion about

unspecified donations reforms to be examined post-election.[91]

A post-election review by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) found

that the arrangement did not contravene entitlements policy and that Parakeelia

had not donated profits from the sale of Feedback to the Liberals.[92]

Same-sex

marriage

The debate around legislating for same-sex marriage, or

marriage equality, was not necessarily a major theme in the campaign, however, it

was a major point of differentiation between the main players. The Coalition

took to the election a promise to hold a plebiscite—a non-binding national

poll—on same-sex marriage, a policy Turnbull inherited when he took over the

leadership of the Liberal Party from Tony Abbott.[93]

In the event of a Coalition win, Turnbull claimed that the Government would

have a mandate to run the plebiscite, and stated that the plebiscite would be

held shortly after Parliament resumed, possibly as early as August.[94]

Labor firmed its position throughout the campaign to a

policy of a vote on same-sex marriage within 100 days of assuming office,

stating it would be the first piece of legislation a Labor Government would

introduce into the 45th Parliament.[95]

Labor, noting its opposition to a plebiscite, maintained that the Prime

Minister would be forced to allow a conscience vote in the Parliament as Labor

would block a plebiscite.[96]

Turnbull, however, did not agree that a vote in Parliament would follow if a

plebiscite was prevented from being held.[97]

Shorten argued that a plebiscite campaign would result in public homophobia,

and stated:

And instead of sitting in judgment, instead of providing a

taxpayer-funded platform for homophobia, we will gift every Australian an equal

right in respect of love. Nothing less.[98]

The Treasurer, Scott Morrison, claimed that opponents of

same-sex marriage were victims of hatred and bigotry for their views:

I know it from personal experience, having been exposed to

that sort of hatred and bigotry for the views I've taken from others who have a

different view to me, but I think the best way is for us all to have a say on

this, deal with it and move on.[99]

The Prime Minister’s view was that the Australian people

should be trusted to have a civilised debate on the issue. He revealed that

Coalition MPs would not be bound to vote in line with the outcome of the

plebiscite, but was confident that if the plebiscite were passed a majority of

MPs and senators would vote to allow same-sex marriage. Some MPs suggested that

they should be free to vote against same-sex marriage if their individual

electorate voted against it in the plebiscite.[100]

The possibility that Coalition MPs would vote against

same-sex marriage regardless of the outcome of the plebiscite lead the Opposition

to claim that the plebiscite was a $160 million ‘opinion poll’ that ‘the

government [would] ignore’.[101]

Negative

gearing and housing affordability

The first suggestion that negative gearing—using losses on

rental properties as a deduction on income taxes—would become an election issue

was a media report in mid-2015 which stated that Labor was considering a policy

to limit negative gearing to purchases of newly-built properties.[102]

Labor took its policy on negative gearing to the election as

one of the major differences between it and the Coalition, which was

interpreted as a sign that Labor was abandoning the ‘small-target’, policy-lite

approach of the 2013 federal election. The Government claimed that Labor’s

policy would drive away investors, drive down housing prices and leave

Australians poor.[103]

A senior Cabinet minister claimed that, under Labor’s policy, ‘the economy will

come to a shuddering halt and I think the stockmarket will crash’.[104]

In April 2016 the Prime Minister ruled out any changes to

negative gearing in the Budget, a change that was reported as being required to

calm backbench MPs who feared the electoral consequences of touching negative

gearing. This also allowed the Coalition to highlight its policy differences with

Labor and to campaign on Labor’s plan which it claimed would increase rents and

decrease home values.[105]

The Treasurer pointed to research which indicated that

Labor’s policy would not affect the wealthiest Australians, but would hit ‘mum

and dad investors’ disproportionately. However, it was soon reported that the

author of the report was linked to a friend of the Treasurer, and contained

factual errors.[106]

One report released by the Government pointed to property

prices falling by between 4 and 15 per cent and rents rising by 6 per cent;

however, the Prime Minister rejected the suggestion that the Coalition was

running a scare campaign on negative gearing.[107]

Other analysts rejected the idea that house prices could fall and rents could

rise at the same time.[108]

Regardless of one’s political orientation it seemed that experts were ready

with analysis to support almost any view on this issue. One pre-election poll

found slightly more people did not believe the Coalition’s claims about Labor’s

policy (40 per cent) than did believe it (30 per cent), with the remaining 30

per cent undecided.[109]

Asylum

seekers and the return of the boats

The issue of asylum seekers who arrive in Australia by boat

has been a persistent feature of recent Australian politics, and the 2016

federal election was no exception. The decision by the Supreme Court of Papua

New Guinea (PNG) that the detention centre on Manus Island was unlawful mere

days before the election was called thrust the refugee and border control

policy back into the spotlight.[110]

The interception of a boat of asylum seekers was used to

support the Government’s argument that Labor was weak on ‘boats’. The Daily

Telegraph newspaper reported ‘People-smuggling gangs are using the prospect

of Labor winning the election as a marketing tool to entice desperate refugees

back on to deadly boats bound for Australia,’ and that ‘Labor’s record of

allowing about 800 boats carrying more than 50,000 people to Australia during

their six years in government is being used to reignite the shameful business

of people smuggling ahead of a tight election campaign.’[111]

Labor’s message on its asylum seeker policy was challenged

by some of its candidates who were disinclined to follow the party line on the

issue. Deputy Labor leader Tanya Plibersek asserted that all of Labor’s

candidates supported Labor’s policy and opposed the Coalition’s policy of

indefinite detention, yet Labor instructed all of its MPs and senators to

delete any social media posts relating to refugee policy.[112]

Later in the campaign, media reporting suggested that more than 50 Labor

candidates opposed their party’s boat turn back policies. [113]

The Government used the apparent lack of Labor discipline to claim that

Shorten’s claim of a tough Labor immigration policy was not credible, and that

it would not survive internal Labor Party pressure.[114]

Labor was not completely alone when it came to such apparent

asylum seeker policy inconsistencies. The Liberal candidate for the division of

Mackellar, Jason Falinski, had also criticised Australia’s immigration policy

in a newspaper article in 2001, but stated that he now supported his party’s

policy wholeheartedly.[115]

Several Nick Xenophon Team candidates also came out in opposition to offshore

detention of asylum seekers, leading to some ambiguity as to what the party’s

policy position was.[116]

Turnbull defended Immigration Minister Peter Dutton when

Dutton claimed on Sky News that many refugees were innumerate and illiterate in

their own language and would both take Australian jobs and ‘languish in

unemployment queues’. Turnbull added that this was no fault of the refugees.

Shorten claimed that the Dutton and Turnbull comments were reminiscent of

Pauline Hanson’s policies.[117]

Some journalists suggested that Dutton’s comments were a

deliberately inflammatory ‘dead cat’ manoeuvre– designed to overwhelm the

debate with emotion, or a ‘dog whistle’—a message designed to resonate with a

certain sub-set of the community.[118]

Regardless of the intention, the Immigration Minister’s intervention steered

the campaign firmly towards refugee issues, which was a strategy anticipated by

Labor, albeit perhaps not so early in the campaign (nine days into an eight

week campaign).[119]

Links were made between other policies and people

smuggling. The Deputy Prime Minister, Barnaby Joyce, linked the suspension of

the live cattle trade by the previous Labor Government to the increase in

people smuggling, due to creating ill-will with Indonesia.[120]

In an editorial the Daily Telegraph suggested that the people smuggling

industry was watching the Australian election:

The people smuggling industry, dormant in Australian waters

since the Coalition fulfilled its 2013 election pledge to stop the boats, is

hoping that Australia’s next government will return to the so-called ‘compassionate’

policies of the Rudd/Gillard governments. You can bet that people smugglers

would have rejoiced at news that Labor would abolish the Howard-era Temporary

Protection Visas that form an effective barrier against illegal arrivals

finding a path to permanent residency.[121]

In the final days of the campaign, Dutton linked asylum

seekers with terrorism, stating that voters wanted stronger border controls

after seeing terrorist attacks such as those that occurred in Paris and

Brussels.[122]

However, a survey conducted by the left-wing think tank The Australia Institute

found that 63 per cent of respondents believed that asylum seekers who arrived

by boat should be bought to Australia, and that Australia should accept an

offer to resettle Manus Island and Nauru refugees in New Zealand.[123]

The

National Broadband Network and Australian Federal Police raids

While the National Broadband Network (NBN) policies of the major

parties was a topic early in the campaign, with Labor promising to use more

fibre and the Coalition claiming that this would lead to cost and time blowouts,[124]

the real NBN story of the election campaign was a raid on the offices of a

Labor frontbencher and the home of one of his staff by the Australian Federal

Police (AFP) in relation to leaked NBN documents.

The NBN company (NBN Co) made a referral to the AFP to

investigate the leak of documents that ALP senator Stephen Conroy had produced

at a Senate committee hearing, and which had been used by journalists, prior to

Christmas 2015.[125]

The raids occurred on the evening of Thursday 19 May 2016, a few days after the

writs for the election were issued, and resulted in documents being seized from

the Melbourne offices of Senator Conroy and from the Brunswick home of one of

Conroy’s staff.[126]

Labor stated that it accepted the AFP’s assertion that it

was acting independently of the Government in the timing of the raids, but also

claimed that the NBN Co would have referred the leaks to the AFP at the behest

of the Prime Minister, who was formerly the Communications Minister, due to the

Government’s embarrassment at the leaks.[127]

Senator Mitch Fifield, Communications Minister at the time of the raid,

admitted that he knew about the investigation (although he stated that he had

no interaction with the AFP), but said that he had not told the Prime Minister

about it. Labor claimed that the Communications Minister not informing the Prime

Minister was implausible.[128]

Labor claimed parliamentary privilege on the documents,

requiring them to be held by the Clerk of the Senate until a determination on

privilege could be made.[129]

On 28 March 2017 the Senate Committee of Privileges recommended that the claims

of privilege be upheld but refrained from recommending that NBN Co be found in

contempt.[130]

A week after the raid the NBN again featured in the election

campaign when the chair of NBN Co, Dr Ziggy Switkowski, published an opinion

piece in which he defended the decision to call the AFP in to investigate the leaks,

claiming it constituted theft. Switkowski also denied NBN cost blowouts and

rollout delays.[131]

In a subsequent investigation into Switkowski’s intervention

requested by Labor, the Secretary of the Department of the Prime Minister and

Cabinet concluded that some elements of the opinion piece were inconsistent

with the caretaker conventions.[132]

The Prime Minister (who had appointed Switkowski when he had been

Communications Minister) defended the Chairman and said he was doing a

‘remarkable job’.[133]

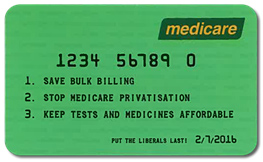

‘Mediscare’

and privatising Medicare

A late—though potent—entry into the election campaign was the

campaign around the privatisation of Medicare, dubbed ‘Mediscare’ by the media.

Although the actual prospect of a privatisation of Medicare was undoubtedly

overblown, the campaign appeared to tap into a fear in the electorate that

Australia’s national healthcare system was in danger in some way.

In August 2014 the Department of Health had sought

expressions of interest for outsourcing the payments functions for Medicare,

the Pharmaceuticals Benefit Scheme, and Veterans’ Affairs.[134]

The expression of interest stated that it did ‘not include the face-to-face

services provided by Medicare’.[135]

The plan was subsequently cancelled.[136]

The Opposition quickly realised that the idea of privatising

any aspect of Medicare was strongly opposed by the public. Regardless of the

veracity of the campaign, veteran political commentator Paul Bongiorno noted

that ‘the electorate is highly suspicious of the conservatives in the health

space’.[137]

A survey by Essential reported that 64 per cent of voters disapproved of

suggestions to ‘outsource the administration and payment of Medicare,

pharmaceutical and aged care benefits to the private sector’, including 74 per

cent of Labor voters, 75 per cent of Greens voters, and 55 per cent of

Coalition voters.[138]

Launching the Medicare privatisation campaign gave Labor a

significant poll boost, leading it to believe that if it could maintain that

momentum it might win between 12 and 14 seats from the Coalition, bringing it

close to a win in the election.[139]

It also forced the Liberal campaign to change its focus to counter the

perception that it intended to privatise Medicare.

In the days leading up to election day the campaign

escalated, with unions handing out one million cardboard flyers resembling Medicare

cards as part of the campaign (see Figure 6)[140]

and Labor promoting the message to non-English speaking voters in their own

language.[141]

However, it was estimated that Labor spent only $776,900 on television

advertising around the Medicare issue, compared to over $2m on advertisements

labelling Malcolm Turnbull as out of touch. Most of the Medicare campaign was,

instead, a targeted online media campaign, using data gathered by large-scale

door-knocking and phone campaigns.[142]

Figure

6: Mock Medicare card

Source: Provided by the National Library of Australia election

ephemera collection.

Malcolm Turnbull made his views of the ALP campaign clear on

several occasions.[143]

In his election night speech Turnbull labelled the campaign ‘some of the most

systematic, well-funded lies ever peddled in Australia’. He further stated:

The mass ranks of the union movement and all of their

millions of dollars, telling vulnerable Australians that Medicare was going to

be privatised or sold, frightening people in their bed and even today, even as

voters went to the polls, as you would have seen in the press, there were text

messages being sent to thousands of people across Australia saying that

Medicare was about to be privatised by the Liberal Party.

And the message, the message, the SMS message came from

Medicare. It said it came from Medicare. An extraordinary act of dishonesty. No

doubt the police will investigate. But this is, but this is the scale of the

challenge we faced. And regrettably more than a few people were misled. There’s

no doubt about that. [144]

Following the federal election, in referring the conduct of

the 2016 federal election to the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters,

the Government included a reference to examine truth in advertising in relation

to political campaigns, including from ‘third party carriage services’ like SMS

messages.[145]

Truth in political advertising laws have been contemplated in the past’,

however, such laws are likely to be problematic in both practical and

constitutional terms.[146]

A post-election survey by JWS Research found that health was

the most important issue in the campaign, with 57 per cent of respondents

nominating heath as a key vote influencer, including 38 per cent specifying

Medicare specifically. Voters who voted on election day, and those who decided

who they would vote for on election day, were more likely to nominate Medicare

as a vote influencer.[147]

The leaders’

debates

The campaign saw three pre-election leaders’ debates. The

first was held in western Sydney on 13 May 2016, after one week of the

campaign, at the Windsor RSL in the division of Macquarie and was hosted by Sky

News and The Daily Telegraph.[148]

The audience of 100 was allowed to ask questions of the two leaders, and 42 of

the 100 declared Shorten the winner, compared to 29 for Turnbull and 29

undecided.[149]

According to a report:

Voters asked questions about childcare, education,

privatisation, government debt and bank interest rates. No one asked about

climate change, same-sex marriage, asylum seeker policy or the small business

tax cuts.[150]

Being broadcast on pay TV, and not shown on the ABC, it was

suggested by one political journalist that the debate was only watched by ‘political

tragics’ and those who had no choice.[151]

It was later revealed that the TV audience for the debate was 30,000 to 40,000

viewers.[152]

A rural affairs debate featuring Nationals leader and Deputy

Prime Minister Barnaby Joyce, Labor agriculture spokesman Joel Fitzgibbon and

Greens leader Senator Richard Di Natale in Goulburn on 25 May 2016 gained

coverage in the mainstream press, mainly for Joyce linking the 2011 suspension

of live cattle exports to Indonesia with the rise in the number of asylum seeker

boats arriving in Australia.[153]

Indonesia sought clarification of Joyce’s claims, and the Prime Minister

dismissed any link.[154]

The second leaders’ debate on 29 May 2016, hosted by the

National Press Club in Canberra, was broadcast on Sky News and the ABC and, in

contrast to the initial ‘people’s forum’, was generally thought of as the

official debate. The Australian newspaper’s political editor, Dennis

Shanahan, stated of the debate that ‘there was no light, no elucidation and no

detail’.[155]

With 888,000 national viewers on ABC and ABC News 24, the debate rated poorly,

and was the least watched debate in the 32-year history of Australian leaders’

debates.[156]

So poor was the reaction to the debate that it led to speculation as to whether

there was any future for the ‘tired and obsolete format’.[157]

Following the Press Club debate the Prime Minister

proposed to hold the third leaders’ debate in an ‘innovative way’ and ‘in the

media of our time’ on social media platform Facebook.[158]

The debate was streamed live on Facebook and website news.com.au on 17 June

2016, and included questions pre-submitted online and from a live studio

audience of 30 undecided voters from 21 marginal seats.[159]

It was estimated that 120,000 people watched the Facebook

stream live, and the 60 minute debate was considered to be tighter, with ‘a

couple of moments of real spontaneity’.[160]

The Facebook debate also pushed the Prime Minister into less comfortable

territory, with questions about the NBN, the same-sex marriage plebiscite and

climate change policy, although the Prime Minister was considered by some

commentators to have performed well.[161]

The studio audience voted Shorten the winner, although he ‘looked angry and

snapped’ at the Prime Minister and the moderator, News Corp journalist Joe

Hildebrand.[162]

Independents:

the class of 2010 comeback tour

Two of the independent MPs that provided the support to

allow Julia Gillard to form a minority government after the 2010 federal

election, Rob Oakeshott and Tony Windsor (both of whom retired at the 2013

federal election), announced they would stand for election in 2016.

Oakeshott was a relatively late entry in the election, revealing

his candidature for the seat of Cowper as the AEC announced the nominations it

had received. Rather than recontesting his old seat of Lyne, Oakeshott stated

he was running against incumbent Nationals MP Luke Hartsuyker in Cowper due to

the redistribution and Hartsuyker backing the privatisation of a local TAFE.[163]

Oakeshott’s bid for the seat inspired NSW premier Mike Baird

to campaign for Hartsuyker, and led to Peta Credlin (Tony Abbott’s former Chief

of Staff), stating that Oakeshott was ‘a cancer in the last parliament’.[164]

Prime Minister Turnbull and former Prime Minister John Howard also expressed

their support for Hartsuyker, a move interpreted by the media as a sign Hartsuyker

was in electoral trouble, despite his 13 per cent margin.[165]

Barnaby Joyce was amongst those who expressed a view that

Oakeshott was only running for the public funding, stating:

He’s made his mind up at five minutes to midnight. I think we

can all smell a rat here. I think it’s got something to do with $2.62 a vote

for a couple of weeks’ work.[166]

Despite admitting to financial issues, Oakeshott denied that

he was running to make money.[167]