Executive summary

- With the human population

expected to peak by the end of this century and long-term

fertility decline projected in high-income countries, Japan’s

negotiation of the challenges of an ageing population and fertility decline offers

an important case study.

- Given the significant impacts of demographic transition on

macro-economic and financial effects, the shape of cities, public policy,

national budgets and political systems, Japan is faced with the considerable

challenge of how to maintain productivity, economic growth and societal cohesion

with a shrinking workforce, smaller tax base and increasing demand for social

services.

- This paper analyses the interactions of several causal drivers of

ageing and fertility decline in Japan, citing policy makers, demographers and population

researchers and commentators.

- Rather than continuing to rely on the traditional methods of

increased efficiency, financial and technological innovation, research findings

and commentary have emphasised reforms at the level of structural organisation.

- This includes addressing cultural norms and values with a

particular emphasis on gender and social roles, socio-economic conditions, the

labour market and workforce expectations, immigration and naturalisation

processes, and electoral asymmetries.

- All of these will in turn have an impact on Japan’s place in the

region and its relationships with its neighbours. The extent to which Japan,

with a shrinking and ageing population, can effectively recalibrate their

policies to address this combination of issues will be of considerable interest

for Australia, in the context of close and growing economic, diplomatic and

defence relationships. It will also be key to realising sustainable,

future-oriented, regionally engaged, long-term outcomes for many countries in

the region which face similar challenges now or in the future.

Introduction

For the first time in recorded history, the human population

is expected to peak by the end of this century. Population decline and the

‘grey spectre’ are affecting mature economies, including Australia. The world’s

population of people aged 60 years and older is expected to double by 2050, while fertility rates in high-income countries

appear to be in long-term decline.

As is evident in the large-scale

civil demonstrations against

raising the pension age in

France since January 2023, policies that support cutting benefits,

increasing taxes and raising the minimum age of retirement can

be vexatious. While the Macron Government has maintained that an older

retirement age helps to preserve the pension system, the 8 major

unions in France have gained popular

support. They argue that low-skilled and low-income workers bear an unfair

burden as they begin their working life earlier and often do high-impact manual

work, whereas other revenue collection methods are available to the state. The

demonstrations have also broadened to include wider concerns relating to

inflation, food and energy prices.

Whichever settlement is reached in that country, it is

undeniable that the scale of demographic shift in the old-age

dependency ratio – the

number of retirees compared to the working age population – is placing greater

financial strain on working populations in affected countries and can aggravate

pre-existing structural problems.

At the same time, low fertility rates are presenting significant challenges for

policymakers, particularly in the countries of the

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Demographics

are closely related to key macro-economic and financial effects, and their

changes can have whole-of-society impacts, ranging from economic and financial

performance to the shape of cities, public policy priorities and political

systems. To what degree and how fast countries with ageing and shrinking

populations can recalibrate their policies will be key to maintaining positive

economic outcomes.

Japan offers an important litmus test among low-fertility

countries in the OECD. As the world’s third-largest economy, it is a peaceful,

prosperous country with the longest life expectancy in the world, the lowest

rate of homicide, a world-leading high-end manufacturing industry, comparatively

little political polarisation, a generous social support scheme, and excellent

public services and infrastructure.

Japan also faces volatile demographic pressures associated

with its ageing and shrinking population. In 2005,

Japan became the world’s first ‘super-aged’ society,

where over 20% of the population is aged 65 or older. As

it continues to innovate to maintain an accustomed standard of living through

increased efficiency in productivity and investment, taxation and financial

policies, in the postwar period the country has steadily increased reliance on

a historically non-traditional workforce – namely women, the

elderly and immigrants.

This paper analyses how structural

organisation and cultural norms, related to gender

equality, socio-economic and labour market conditions, minorities and

immigration, are important interconnecting drivers

to consider in formulating sustainable policy priorities related to retirement

age, taxation, social security and other associated factors.

Overview of ageing populations and fertility decline in Northeast Asia

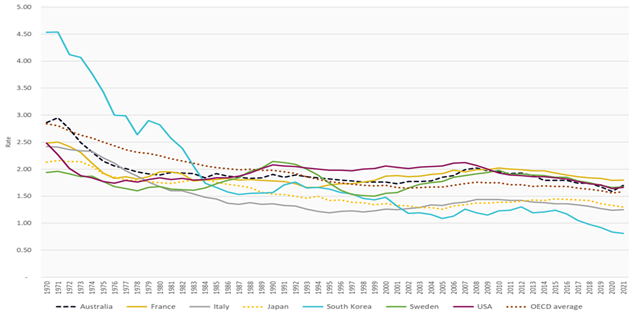

Among economically advanced countries, as demonstrated in

Figure 1 below, the ‘lowest-low fertility’ rates are particularly pronounced in

3 regions: Northeast Asia, and Eastern and Southern

Europe.[1]

Figure 1 Fertility trends in

selected OECD countries 1970–2021

Source: OECD Family Database

For countries with consistently low fertility rates and

where the numbers of deaths exceed the number of births, without inward

migration, a decline in population is inevitable over the longer term. Among

Northeast Asia’s dominant economies – Japan,

South Korea and China – all are

experiencing unprecedented and rapid population ageing, and have reported drops

in population growth in the past year. Singapore, Thailand and Taiwan are also

shrinking, while population growth is slowing in Vietnam, the Philippines and

elsewhere in East Asia.

Japan was the first country to reach the median age above 40

(in 1999) and it reported the highest median age in the world in 2021 at 48.4. A

third of Japanese people are over 60, making Japan home to the oldest

population in the world, after Monaco. Japan is also among the ‘lowest-low

fertility’ countries, beginning its population decline in 2008 and posting its

total fertility at just below 1.3, or 811,604 births in 2021, well below the

replacement level of 2.1.[2]

South Korea’s population – currently just under 52 million,

and with the lowest birth rate of OECD member states in 2021 – is projected to drop below 38 million

by 2060; by 2100, its population will have dropped below 16 million, less than

a third of what it is in 2023. South Korea’s working

population is estimated to decline by 35% until

2050, based on current fertility rates. Taiwan is likely to see a 28.6%

reduction. Both South

Korea and Taiwan

will become super-aged later this decade, and their working-age populations

also are shrinking, a trend that will accelerate over the next several decades.

Of global and regional significance is the recent

demographic shift in China in 2022. China’s

population decreased by 850,000

to 1.412 billion

due to a slip in its fertility rate to below

1.1 from its peak of 6.0 in the 1960s. Although

likely exacerbated by COVID and its associated impacts, estimates find that by

2035, 400 million people in China will

be age 60 and over, representing 30% of the population. The UN’s

medium estimate predicts that China’s total fertility rate will rise from

1.18 children per woman in 2022 to 1.48 in 2100. The UN’s low

case estimate projects that China’s population may fall to 1.3 billion by

2050 and 800

million by 2100, a third of the current total, while the Shanghai

Academy of Sciences estimates that it will reach 587 million in 2100, less

than half of the current total. This comes at least a decade earlier than

projected. Moreover, for the working-age population in China, more than 40

million will retire in the current 5-year period to 2025,

dropping

by 35 million in this period due to a

lack of replacement, and experiencing a decrease of over

186 million people over the next 27 years.

Some of the

possible factors in China’s population decline include years of falling

fertility, low or negative net migration, the consequences of the previous one

child policy (1980–2016), the rising cost of living,

the impacts from COVID-19 and higher incomes for women. China has one of the

lowest retirement age plans in the world, however, with female factory and

agricultural workers retiring at 50 and male workers at 60. In response, China

is campaigning for young people to get married and have multiple children while

also gradually

raising the retirement age to prepare the population for delayed

retirement.[3]

Japan – a demography laboratory for

‘new capitalism’ policies

In Japan, demographic trends in fertility, longevity and

immigration are certainly stark,

and have earned it the moniker of ‘demographic

policy laboratory’ among OECD countries and the Group of Twenty (G20).[4]

The population

is projected to shrink well into the middle of this century, dropping to an

estimated 88 million in 2065 – a 30% decline in 45 years – and

to 72 million in 2100.

Dubbed the ‘lost decades’, Japan’s

economic and societal gridlock triggered by the bursting of the property

market bubble in 1991, has produced prolonged anaemic economic growth and wage

stagnation. Contributing factors have included ageing population, labour

shortages, slower consumption, a hollowing-out of the manufacturing sector,

greater fiscal deficits and lower interest rates.

Together with an ageing population, which is finding it

difficult to retire because of the pressure on healthcare and pensions, younger

generations are experiencing less take-home pay and have shown a marked

hesitancy to start families as part of reduced optimism among

Japanese youth in general.

In recognition of the problem of fertility decline, on 19 January 2022, Prime

Minister Kishida Fumio launched a plan for a ‘new

capitalism’ at the World Economic Forum. Mr Kishida then used

his first speech in the new session of Parliament on 23 January 2023,

to announce unprecedented levels of spending in 2 priority areas: child care

support and defence.

Japan’s new national

security strategy, a basic defence program and

a medium-term plan to improve Japan’s defence capabilities commits 43 trillion yen (A$483.7

billion) over 5 years from fiscal year 2023; 56% more than the current program and the highest defence budget ever recorded in the

history of modern Japan. This includes the capability to conduct long-range and

pre-emptive strikes on enemy bases (for example, reinforced missile systems on

the Nansei Shoto (Southwest Islands)). This will likely see a tax hike

of one trillion yen (A$11.2 billion) by fiscal year 2027, increasing the

overall budget for fiscal year 2023 to about 114 trillion yen (US$837.3 billion).

Japan is estimated to have the highest

public debt relative to GDP (gross debt-GDP ratio) of any country in the

world; an estimated national debt of 263%

the size of its A$7.5 trillion economy. Japan spends more on debt

redemption and interest repayment than on public works, defence and education

combined. The International Monetary Fund (IMF), among other financial service

institutions, has indicated that age-related spending pressures are likely to

produce sovereign

stress.

The Kishida administration is

proposing to normalise monetary policy, reviewing its extraordinary stimulus

program as part of the Abe administration’s ‘three arrows

strategy’ (‘Abenomics’), while raising wages

higher than the rate of inflation. Known as the ‘defence tax’, the Government

is proposing to introduce 1% of

current income tax payments, as well as corporate and tobacco taxes. As this

initiative is likely to be contested

by the Keidanren (Japan Business Federation),

which prefers a flat tax, as a fall-back option, the Government may rely

on government and construction bonds, and avoid a review of the taxation system,

which would involve corporate

and income taxes for higher earners.

Although comparatively less

widely reported, the second key policy of child care reform is aimed at

reversing fertility decline. Japan has not enjoyed a replacement

birthrate since 1974. Described by Mr Kishida as a threat to ‘the very survival of the

nation’, the

number of babies born in Japan in

2022 fell below 800,000 for the first time since records began in 1899, 8

years earlier than projected. Japan is

one of the first OECD countries to experience population decline and its fertility

rate of 1.3 has been consistently low compared to the US and Australia at

1.7 and 1.6, respectively. In the 2010s, more than 20% of the population was

older than 65. And in the three-year period 2022–2025, Japan’s entire postwar

baby-boom population will pass the

75-year milestone. During the next 2 decades, Japan’s future decline will

continue to magnify – by roughly 8 million in the 2020s and 10 million in the

2030s.[5]

To avoid a demographic cliff, and to maintain a sustainable

level of productivity and economic growth with a smaller workforce and reduced

tax base, Mr Kishida announced that the Government would institute a Children

and Families Agency to administer the doubled budget

for children as outlined in the Basic Policies on Economic and Fiscal Management and

Reform to be released in June 2023. This

includes pay rises in the fields

of care giving, child care and child education, and in the nursing profession.

The new child support program will require annual funding exceeding one

trillion yen (A$112.9 billion).

Providing cash incentives

for having babies, generous parental leave policies and free or subsidised

child care is not a new approach. Past

financial initiatives to encourage families to have more children, such

as in Australia in 2004, have tended to create only a temporary

bulge in numbers of babies and a momentary spike in the birth rate. Citing

examples of reversed fertility decline in

Sweden, some

demographers argue that without also

addressing social welfare, employment and labour market conditions, gender

equality, access to education, housing affordability and supply chain issues, a

decline in national birth rates is likely to continue.[6]

‘Womenomics’

Despite the many freedoms for women that were enshrined in the Japanese

constitution in 1947, the stereotypical

roles of ‘model employee’ and ‘ideal homemaker’ have remained stubbornly

consistent; divided between the man, husband and father who dedicates long

working hours in fealty to the company or organisation, and the woman, wife and

mother who devotes herself to child-rearing, housework and family

responsibilities.

Women in Japan have experienced dramatic increases in

educational attainment and female labour force participation rates are

relatively high. Japanese women’s

labour force participation has at times outpaced that of the US. Japan

boasts a strong social support system and has increasingly adopted

family-friendly policies to encourage more flexible ‘work-balance’

arrangements, including relatively generous parental leave for mothers and

high-quality child care. Yet, Japan remains one of the most gender-inegalitarian

low-fertility countries in the world.[7]

In recognition of the association between female labour

force participation and fertility levels, the

Kishida administration has continued the ‘womenomics’ policies of the Abe

administration by making it compulsory for companies with over 300 employees to

disclose pay discrepancies between women and men.[8]

This is specifically focused on competing with US and European companies by

attracting Japan’s elite female graduates to Japanese corporations, which are

newly promoted as inclusive, diverse and family-friendly workplaces that have

redressed their customary

gender barriers.

As part of the Kishida plan to implement a ‘virtuous cycle

of growth and distribution’, on 19 January 2023, the Minister of Women’s

Empowerment and Gender Equality, Ogura Masanobu, declared the administration’s

intention to ‘mainstream gender issues’. This

involves increasing female participation in traditionally

male-dominated areas, including in digital/STEM education; women’s entrepreneurship in start-ups; women’s roles in a decarbonised

society; disaster prevention and peace and security; and increasing gender-egalitarian awareness of men and youth.

In 2021,

women earned on average 22.4% less than their male counterparts and held

only 17% of Japan’s total wealth (in 2022, Japan

placed 116th out of 146 countries in

gender gap rankings). Women remain overwhelmingly underrepresented in corporate

managerial positions (13%) and as parliamentary representatives (10%).

Moreover, women remain overrepresented in irregular

employment.

Causal drivers of fertility decline

– some theoretical frameworks

Social demographers such as McDonald, who utilise Gender

Equity Theory, have emphasised

structural changes, including women’s shifting gender roles in the public and

private spheres as a causal driver in fertility decline.[9] Although women

have increased their access to higher education and labour market

participation, they typically continue to face unequal expectations in terms of

child care and housework. These scholars maintain that improving women’s

economic opportunities and changing gender-inegalitarian family institutions

would effectively address the balance (for example, gender relationships,

discrimination, attitudes, and policies).

The Gender Equity Framework is often placed in contrast to Second Demographic

Transition (SDT) theory. In contrast to the first demographic transition

that involved twin declines in mortality and fertility, SDT seeks to explain

sub-replacement fertility trends in primarily Western countries as based on

widespread value or ideational change. Such change includes religious

secularisation, a separation between marriage and procreation, increased

population movement and a transition from materialist to post-materialist

societies (that is, self-realisation and individualism).[10]

To an extent, SDT is complemented by Gender

Revolution Theory, which focuses on the transformation of gender roles in a

changing society to explain both local and regional variation in fertility

decline. This theory identifies 2 main phases in societies experiencing the

‘shrinking family’ phenomenon:[11]

- a trend towards smaller families due to women’s increasing

participation in the labour market, delaying marriage, decreasing the

probability of marriage and delaying childbearing, as well as an increase in

divorce

- increased fertility rates together with increased women’s labour

participation.[12]

The Gender Revolution Theory in the second phase, also

reverses the trends normally linked with SDT, in which men (or full-time

partners) are more involved in caretaking responsibilities, such as housework

and family relationships. This co-parenting and shared caretaking is associated

with family stability and higher fertility in countries with ultra-low

fertility.[13]

Like SDT, however, Gender Revolution Theory also tends to

occlude distinctive and heterogeneous sociocultural characteristics in

non-Western countries.[14]

It is consequently criticised for its unidirectional and deterministic

trajectory which assumes that self-actualisation is experienced in the same way

by men and women across socio-economic conditions and in different cultures.[15]

Similarly, while Gender Equity Theory might offer a link

between women’s labour market opportunities, cultural norms and expectations, and

low fertility in more affluent countries, it also remains limited to factors

which are attributable to individual behaviour and agency.[16]

Given the spectrum of individual attitudes and behaviours (in addition to

contextual differences within and across countries), it is difficult to produce

empirical aggregate studies on fertility decline by focusing solely on these.

Rather than individuality and self-actualisation, in the

Japanese context in recent decades it appears that socio-economic conditions

and existing gender-essentialist social organisation continue to inform

fertility choices. Labour market structure and workplace norms, which encourage

employees to work

long hours, see 53% of female employees

work in part-time

or low-paid jobs. These play an important part for a majority of women in

deciding to leave the labour force at least temporarily around the birth of

their first child.[17]

These women are typically placed in a position of greater dependency on their

husbands’ salaries (as non-marital child-bearing and single-parent

households have remained at negligibly low levels) and the generous social

support and retirement arrangements therein. Although this may change over time,

these factors continue to inform the postponement of marriage and childbearing.[18]

While studies of full-time couples in Japan have shown that

males often maintained gender-egalitarian

attitudes, their caretaking responsibilities were severely curtailed due to

workplace demands compared to their female partners, who ‘tacitly accepted’

more housework.[19]

Moreover, practical realities such as the cost and relatively short opening

hours of child care centres also make it less feasible for both parents to work

full-time (alongside commonly longer office hours

than in other OECD countries).

Compounded by economic uncertainties, including the rising

cost of living and divergent work opportunities between social strata within a gender-essentialist

social structure, these factors contribute to the social and economic context

for the low fertility rate in Japan.[20]

Immigration: a viable option for

reversing fertility decline in Japan?

Together with fertility

rates, Japan’s work force and labour markets have steadily

shrunk since 1990. While Japan’s

population is set to shrink to 100 million in 2050 from 128 million in 2010, Japan's working-age population (aged 15–64 years)

sank to just

over 75 million in 2020, comprising just below

60% of the population and down 13.9% from

the 1995 peak. While the working age population rose from 80 million in 1950 to 100 million in 1990, it is projected to decline to 60

million by 2050. Since the

1970s, Japan and South Korea have

off-shored much of their production to Asia-Pacific countries with a younger

median age and larger and cheaper workforces (for example, Bangladesh, India,

Indonesia, Philippines, Vietnam). Countries such as the Philippines, and

increasingly Vietnam, also have some of the world’s largest

sources of emigration.

At the same time, Japan has long

maintained strict immigration policies with popular support. Roughly 3% of

Japan’s population is foreign-born, compared to 15% in the UK and 30%

in Australia. The traditional consensus on

immigration policy in Japan, characterised by the nation’s ‘insular mentality’, has been such that attempted

reforms have typically

been regarded as a political death-wish.

This has placed Japan at a critical juncture, in which it

faces an acute demographic crisis and resulting labour shortage that will

require it to more than quadruple its foreign workforce (to an estimated

6.74 million) just to maintain current levels of economic output.

Government policy over the longer term has been to

compensate for the shortfall in the national workforce by investing in

‘labour-saving technologies’. Prime

Minister Kishida’s plan for a ‘new form of liberal democratic capitalism’

has not

deviated from this strategy; investing in AI technology, the Internet of

Things (IoT) and robots to improve anything from traffic accident statistics to

remote, automated health care to information flows through machine learning (that

is, as consistent with the Fourth Industrial Revolution).

On the other hand, enhanced efficiency and velocity in the

industrial, social services and financial sectors are not always constructive,

as they also contribute to increased unemployment (particularly in the

‘low-value’ workforce) while exacerbating pre-existing structural problems such

as income inequality.

Nonetheless, under combined demographic and industrial pressures,

Japan has also increased its population of foreign workers from one million in

1990 to 1.72

million foreign workers in October 2020 (although this

number is likely higher), out of more than 2.9 million

residents of foreign nationality in total (or, 2.39% of the total

population of 125.5 million).

In 2018, the Abe Government introduced a new guest worker

program under the ‘Specified Skilled Worker (SSW) i & ii statuses’ to bring

an estimated

345,000 foreign workers to Japan over 5

years. When this program came into effect in 2019 it permitted skilled

blue-collar workers in only 2

of 14 sectors with labour shortages –

construction and shipbuilding – to renew their visas and bring their families

to Japan. The Kishida administration has since expanded eligibility for visa

renewal in all 14 worker-shortage categories.

Despite this recent boost in foreign workers, the official

number based on Japan’s limited definition of ‘immigrant’ provided by the

Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (for example, permanent resident of

foreign nationality, which requires over 10 years of residence in Japan),

estimates only 1.8 million foreign workers as reported by around 300,000

companies.[21]

Given the discrepancy between foreign residents and workers, it may be that not

all companies are reporting their foreign workers and that some foreign

residents are students, self-employed, retired or have moved from their

original jobs.

Higher fertility in immigrant populations is often regarded

by policy researchers as one way to assist in resolving shrinking and ageing

populations, by revitalising communities in decline.[22]

Immigrant populations in Japan, however, have typically recorded lower

fertility rates than their native counterparts.[23]

High social and legal barriers and utilitarian

treatment faced by foreign

workers, as well as harsh

immigration detention policies, have tended to undermine the social

integration of immigrant populations as permanent members of society (for

example, naturalisation, social inclusion and immigrant population growth).[24]

As the late prime minister Abe

Shinzo stated in 2018, for example, the boost in immigration has been

primarily to fill short-term labour needs with ‘human resources with a certain

level of expertise while limiting their length of stay’. These ‘human

resources’ have primarily been international students who work part-time and

trainees registered in the Technical

Intern Training Program. This program has been a boon to companies, which

can hire young, unskilled workers on low wages – but still

higher than those in developing countries.

This situation was exacerbated in

the COVID-19 years as the Suga and

Kishida governments implemented strict border control policies, including an

initial re-entry ban on long-term residents who

were outside of Japan and a complete entry ban on new foreign residents.

This triggered secondary effects such as xenophobia and the scapegoating

of foreigners based on ‘security and

order concerns’, and pseudo-scientific explanations for foreigner-transmission

of COVID. The ban was lifted in 2022 to admit entry to a waiting list of

eligible workers.

While by no means limited to Japan, immigration programs can

also be fertile ground for polarising narratives in host societies. With demographic

transition as a primary concern under an overarching theme of decline and existential

threat and exacerbated by heightened economic insecurity, anti-immigrant,

identitarian or ethno-nationalist ideas such as replacement theory can become popular. Replacement theory, which anticipates the substitution of an imagined

homogeneous and harmonious majority population

with a disruptive immigrant minority

population, has received greater public attention

in recent years. It has been reported to have had some influence in some countries

in Europe, India, the Middle East, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South

Africa and most visibly, in the

US, and has

been linked to acts

of violence perpetrated by individuals and

groups.

Given that Japan’s rapidly ageing population is expected to

need 21

million workers in 2040, a disproportionate growth in the secondary

industrial sector for social security-related services will increase demand for

nurses and long-term care givers in the health and social services sectors, and

for migrant female workers from Southeast Asian countries on temporary visas in

particular.[25]

One way to understand Japan’s conflicted need for foreign

workers and population growth alongside a notably deep reluctance to

permanently include immigrant communities is the political context. As in many

countries, working populations in Japan migrated from rural villages and towns

to the cities for employment in waves in the

1930s, 1950s and since the 1980s. Serviced by

construction, transportation and infrastructure programs, elderly, rural

populations typically represent the traditional strongholds of the Liberal

Democratic Party (LDP). These electorates also

enjoy a disproportionate

degree of influence compared to the more densely populated peri-/urban

voting districts. And they are strong advocates for

the (protected) agricultural industry and social security spending.

As much as the more conservative

electorates may seek to preserve their ‘way of life’ and ideas of the Japanese

nation and identity, as they rapidly age and pass away, and as

the continuing

trend in diversification of political

parties and increasing prominence

of some female politicians albeit relatively few in number, demographic and

political change may follow, including immigration

and further electoral reforms and incoming migrant populations.

Japan’s attractiveness to foreign worker populations is

not a given, however. As the Southeast

Asian region is tipped to become the economic powerhouse that East Asia has

been for at least the past 30 years, future economic growth in primary

emigration countries such as Vietnam, Indonesia, and the Philippines, may

reduce future foreign labour supply in Japan. The Japan

Centre for Economic Research (JCER) estimates that

by 2032 the wages

of factory workers in these countries will rise to more than 50% of those

earned by trainees under the program. Japan’s wages are already among the lowest in developed countries,

and the weak yen further suppresses the earning potential for foreign workers.

Although the political establishment in Japan is such that

it seems unlikely to find the will to overcome entrenched cultural norms and

suddenly declare Japan an ‘immigration nation’, the LDP is likely to continue

to prioritise less contentious (and more popular) factors which inform

fertility intentions such as child care, gender inclusivity and working

conditions, as a national security issue.

Eventually, a formalised immigration policy may assist Japan

in adapting to shared

challenges with countries in the region

through the development of regional and multilateral interconnectedness. Investment and cooperation in renewed

infrastructure, energy systems and urban

redesign, for example, as well as the provision

of more affordable housing and quality education and skills, could better

support Japan’s resilience to the impacts of demographic transition.

Demographic

change in the Indo-Pacific

Demographic change is a worldwide phenomenon with global

implications. Often understood as the ‘flying

geese model’ of Asian economic development, rapid economic growth that

drove Japan’s successful return to the world economy in the 1950s and 1960s,

followed by other now powerful economies in Northeast Asia, were fuelled, in

part, by ballooning labour pools which are now shrinking.

Currently, the cascading effects on national economic and

political power in countries in Northeast Asia, albeit on different timelines,

are being felt at all levels. Alongside structural and cultural factors in

Japan as explored above, with working-age populations shrinking in parallel,

political and budgetary pressures will become more acute in the region. Demographic

change will steadily alter regional security dynamics and demand adjustments to

manage both existing security challenges and to meet new ones.

Beyond Japan, in the broader Indo-Pacific region, it is

estimated that 11

of 16 major security actors will also reach ‘super-aged’ status by 2050.[26]

The Indo-Pacific, which is both a security concept and a geographic area, now constitutes

the majority of the world’s population with many lower income countries with relatively young

populations. It is the region in which world population growth will

occur before peaking at the end of

the century. India

has now overtaken China as the world’s most populous state. And other

states with large, younger populations such as Vietnam, Indonesia, the

Philippines and Bangladesh are anticipated to continue to grow in the next

several decades.

Through the security lens, the Indo-Pacific region is

growing increasingly complex

with a more diverse set of actors with greater distribution of power and

interests. With demands for increased participation in regional security over

the next 30 years, the regional security environment will become more

multipolar in nature.

At the same time, the US, with the

highest military budget in the world, continues to expand its military, while

Australia, China, Indonesia, India, Japan and South Korea all have increased

their military budgets and military activities in the past decade. Moreover, all

regional countries that are security allies with the US (except the

Philippines), are focused on offsetting military recruitment deficits and higher

labour costs by integrating high-technology, including in the cyber and outer

space domains.

Japan, for example, cannot obtain a

workforce at the scale required to build an industrial manufacturing base and

military capacity necessary to project power comparable

to that of China and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Since the first

Abe administration in 2006, at least, increases in defence spending and

national security strategy revisions in Japan have supported a military

transformation focused on high-technology capabilities requiring fewer

personnel, and greater interoperability with allied countries, alongside constitutional

revision.[27]

As stated by the Defence

Ministry in 2020, of priority is ‘reinforcing the human resource base in

light of the aging [sic] population with a declining birth rate and reinforcing

the technology base due to advances in military technologies’. [28]

In continuation of this trajectory, the Kishida administration’s push to reverse

fertility decline to raise the national birthrate and boost the military budget

can be understood as an interlocking program of rapid strategic and economic

transition.

Japan serves as an example for Australia, which currently

has a falling

birthrate and which is predicted to stabilise at 1.62 after 2030. The

Centre for Population has forecast that Australia’s population will increase by

an additional 4 million people to reach 30.8 million by 2032, but this may not

be sufficient to address the

country’s needs.[29]

Although Australia has proven capable

of adjusting to significant

demographic changes, due to abundant

natural resources and population increases through migration, it is also

considered to be in relative decline

due to its smaller population, domestic market and industrial base, longer

supply chains due to geography, and limited manufacturing

capacity compared to other OECD countries. Like

Japan, Australia’s migration

system is currently under review, so as to reduce overreliance upon an ‘uncapped, unplanned temporary program’ and

to increase pathways to permanent residency.

Australia’s resilience also relies upon strong purchasing

power and a solid network of security partnerships. The latter includes its traditional

allies, the US and the UK (as reflected in the AUKUS

agreement), as well as newer partnerships with Japan, South Korea, India,

Indonesia, Singapore and several Pacific Island countries.

Like Japan and several other countries in the region,

Australia faces the ‘exquisite dilemma’ of relying upon China as its largest

trading partner, which is also widely considered to be its biggest security

concern. As demonstrated with some of the constraints

and challenges

in the AUKUS nuclear submarine program (Pillar I), Australia will seek to

expand its industrial base (including building a skilled workforce capacity)

alongside the integration of quantum technologies, artificial intelligence and

autonomy, advanced cyber, counter/hypersonic capabilities and electronic

warfare (AUKUS

Pillar II).

Australia stands to learn valuable lessons from Japan and

other countries in Northeast Asia, as they negotiate a host of interrelated

realities in ‘super-aged’

societies. It is also well-placed to engage in reciprocal exchange with younger

and growing regional neighbours as they manage the opportunities of short-term

‘demographic dividends’ together with the attendant pressures of rapid growth,

while also seeking to stabilise the regional balance of power. And with the

immediate and urgent, direct and cascading security impacts from large-scale

and accelerating climate change also affecting the region, as with the case of Australia, many states will see increasing pressures on

their militaries to provide additional assistance for internal and external humanitarian

security engagements.