Political donations for Australian federal

elections are regulated by Part XX of the Commonwealth

Electoral Act 1918 (the Act). Donors, political parties, associated

entities and political

campaigners are required to submit an annual return for each financial year

to the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) detailing any donations they make

or receive above the disclosure threshold. The disclosure threshold is indexed

annually and is $14,000 for the 2019–20 financial year.

Annual returns covering each financial year are published by

the AEC on its Transparency Register

on the first business day of February in the following year. States and

territories generally have their own political finance regimes for state and

territory elections, which are discussed in detail in the Parliamentary Library

publication Election

funding and disclosure in Australian states and territories: a quick guide.

Under Part XX of the Act disclosure of any money received consisting

of amounts that are at or below the threshold is not required. While some

political parties voluntarily disclose some donations (‘gifts’ in the Act) that

are below the disclosure threshold (see below), this means that a proportion of

the income that Australian political parties use to fund their election

campaigns and operate comes from unknown sources. Funds which can be used in

election campaigns that come from undisclosed sources have been referred to as

‘dark

money’.

Undisclosed money is simply the difference between what a

party records as its total income in a financial year, and the sum of its

reported money received—donations and other receipts. This information is

readily available on the AEC Transparency Register.[1]

Both party returns and donor returns provide information

about money in politics. However these two sources are often difficult to

reconcile, with some donations only listed on one of the two sources, or

aggregated in different ways.

It is important to note that donations do not constitute the

entirety of political parties’ incomes. Political party returns also list

non-donation income received above the disclosure threshold as ‘other

receipts’, and can also receive public funding in respect of elections. The

‘other receipts’ include membership fees and income such as proceeds from asset

sales or returns on investments. In addition, as well as setting out income,

political party annual

returns also list total annual expenses and debts.

The extent to which political party finances should be

entirely open to the public is a matter of debate (parties may have commercial-in-confidence

arrangements with suppliers, for example), however there is a public interest

argument for knowing who

donates to political parties.

What are party funds used for?

Like most sizeable organisations, political parties have a

range of expenses such as operating costs (salaries, rent, office expenses and

so forth). A regular (and major) expense for political parties is the funding

of election campaigns. Under Commonwealth electoral law political parties are

not required to disclose their campaign spending, and because returns cover a

financial year and so are often not aligned with election periods, it is not

possible to determine party campaign spending from reported total expenditure.

As a result we do not know how much Australian federal election campaigns cost.

In contrast, most states and territories do require parties to reveal how much

they spend on state and territory elections, and in New South Wales, South

Australia and the Australian Capital Territory the amount they can spend is

capped.

Parties that wish to receive public election funding

(calculated at a specific

rate per vote received in respect of candidates who receive more than four

per cent of the vote) are required to submit a claim detailing election

spending—however the details of the claims are not public, only the final

amount that the AEC pays (parties can also receive public funding from state

electoral authorities). For the 2019 federal election parties and

candidates were paid a total of around $70 million in public funding, of

which around $27 million went to the Liberal Party (around 40 per cent) and $24

million went to the ALP (around 35 per cent). There is no public information on

how parties spend this money.

How much money is from undisclosed

sources?

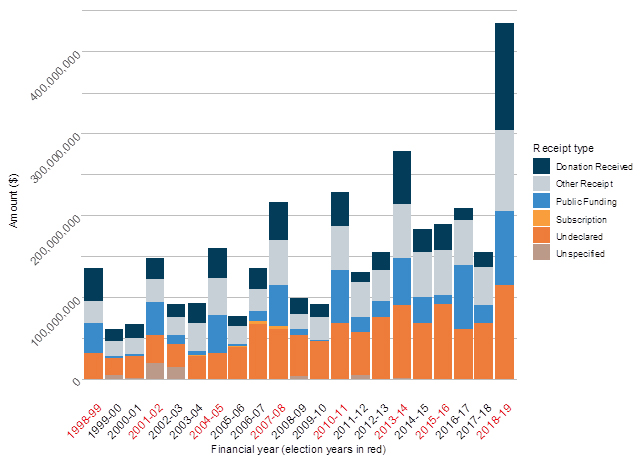

The amount of money from undisclosed sources in political party annual returns differs from year to year, although it is generally higher

in an election year (the red highlighted years in Figure 1). In 2018–19, the

most recent year for which data are available and the year which included the

2019 federal election, just under $115 million was undisclosed by political

parties—over one-quarter of total income ($434.8 million). The total amount

between 2006–07 (when the disclosure threshold was increased to $10,000) and

2018–19 is just over $909 million; the annual average is about $70 million

(data on the amounts is in Appendix A).[2]

The amount varies by political party. For 2018–19, for

example (see Table 1 below), the Liberal Party reported the largest amount at

$59.2 million of its total $165.2 million income (almost 36 per cent of total

income). While Labor and the Greens have stated that they report

donations of, respectively, over $1,000 and $1,500 or more, the two parties

still account for around $38 million between them—$27.6 million for Labor

(almost 22 per cent of total income) and $10 million for the Greens (49 per

cent of total income). Seventy-nine per cent of the total income of the One

Nation Party is unreported, the largest proportion of undisclosed money

relative to total income of all of the significant parties, suggesting that the

party possibly has a large number of small donors.

Figure 1: Total reported receipts by type (federal)

Note: For the purposes of this chart any money received from

the AEC (or a state or territory electoral commission where the party has

listed that as a receipt in their returns) has been classified as ‘public

funding’. Receipts are classified as ‘subscription’ in a small number of

returns, however this does not reflect standard present practice. Selected data

for the table is in Appendix A.

Source: Parliamentary Library analysis of AEC data.

Table 1: Reported and unreported income by party in

2018–19

| Party |

Total income ($) |

Disclosed ($) |

Undisclosed ($) |

Undisclosed (%) |

| Liberal Party |

165,274,107 |

106,006,985 |

59,267,122 |

35.86 |

| Australian Labor Party |

126,279,024 |

98,656,531 |

27,622,493 |

21.87 |

| Others |

103,706,739 |

94,044,491 |

9,662,248 |

9.32 |

| The Greens |

20,409,109 |

10,406,605 |

10,002,504 |

49.01 |

| The Nationals |

16,114,060 |

10,338,157 |

5,775,903 |

35.84 |

| One Nation |

3,023,689 |

632,780 |

2,390,909 |

79.07 |

| Total |

434,806,728 |

320,085,549 |

114,721,179 |

26.38 |

Source: Parliamentary Library analysis of AEC data.

The laws around disclosure of donations make it relatively

easy to donate an aggregate amount greater than the disclosure threshold to a

political party but not have that donation disclosed. The most straightforward

way to do this is for a donor to make separate donations at or below the

disclosure threshold to each of a party’s state and territory branches. For a

party with branches in each state and territory, this means a single donor

could donate a (maximum) total of $112,000 (eight x $14,000) without being

required to disclose the donations.

In addition, the provisions of the Act that relate to

political party annual returns require the party to declare any donation where

‘the sum of all amounts ... is more than the disclosure threshold’

(subsection 314AC(1)), but that ‘in calculating the sum, an amount that is

less than or equal to the disclosure threshold need not be counted’ (subsection

314AC(2)). So, for example, 25 individual donations of $10,000 in one year to

one party—$250,000 in aggregate—would not count as being above the disclosure

threshold, and would not need to be reported by the party. The requirement for

reporting by individual donors is more stringent as the Act requires that a

donor must report donations ‘totalling more than the disclosure threshold’

(section 305B). But if a donor to a party did not comply with this, and the

party concerned did not disclose the aggregate amount received from that donor

because it was not required to, the AEC would have no way of knowing about the

donor in order to pursue them for compliance.

How effective is the disclosure

threshold?

While the AEC’s donor

disclosure return form specifies the amount of the disclosure threshold for

the given year, a large number of donors elect to complete a return and list

donations that are well below the disclosure threshold. Donors have disclosed

donations of as

little as $1.

Since 2006–07, below-threshold donations to political

parties disclosed by donors have averaged $5.45 million per year (an average of

23 per cent per year of total disclosed donations) (see Table 2 below). The

2018–19 financial year appears to be an outlier due mainly to the unusually

large donations received by the United

Australia Party in the reporting period. As noted above, donors are

required to declare below-threshold donations if the total amount of their

donations exceeds the threshold, and most (although not all) of the disclosures

set out below are due to this requirement.

Table 2: Donor returns donations below the disclosure

threshold, 2006–19

| Financial Year |

Threshold amount

($) |

Below threshold

disclosed ($) |

Total disclosed

($) |

Below threshold

(%) |

| 2006-07 |

10,300 |

4,950,298 |

18,077,096 |

27.38 |

| 2007-08 |

10,500 |

5,891,279 |

26,484,088 |

22.24 |

| 2008-09 |

10,900 |

3,546,389 |

12,437,390 |

28.51 |

| 2009-10 |

11,200 |

3,603,430 |

13,367,801 |

26.96 |

| 2010-11 |

11,500 |

5,886,113 |

27,797,959 |

21.17 |

| 2011-12 |

11,900 |

3,660,553 |

12,929,886 |

28.31 |

| 2012-13 |

12,100 |

5,214,448 |

19,664,286 |

26.52 |

| 2013-14 |

12,400 |

7,021,860 |

58,539,100 |

12.00 |

| 2014-15 |

12,800 |

4,917,540 |

24,082,643 |

20.42 |

| 2015-16 |

13,000 |

8,580,588 |

31,041,252 |

27.64 |

| 2016-17 |

13,200 |

4,034,911 |

15,425,763 |

26.16 |

| 2017-18 |

13,500 |

5,629,735 |

19,242,277 |

29.26 |

| 2018-19 |

13,800 |

7,920,599 |

121,476,994 |

6.52 |

| Total |

|

70,857,743 |

400,566,535 |

17.68 |

Source: Parliamentary Library analysis of AEC data.

The $70.86 million in disclosed below-threshold donations

over the period 2006–19 (approaching 18 per cent of total donations disclosed

by donors in the same period) gives an indication of how much money enters the

system in this way.

An examination of the detailed donor returns also suggests

that some donors are declaring donations that political parties are more likely

to record as ‘other receipts’. For example, a number of donors have disclosed

donations for attendance at dinners. A party, for its return, might consider

that the money paid to attend a dinner does not constitute a donation as a meal

was provided in return, and hence records the money as an ‘other receipt’. In evidence

to the Parliament the AEC has stated that that Act is not clear on the

handling of these situations and that this has been a longstanding issue.

Conflicting and occasionally contradictory rules, both

within the federal disclosure regime and in the interaction of the federal rules

and state/territory rules, also serve to lessen the effect of the federal

disclosure threshold.

In a 2019 decision (Spence v. State of

Queensland) the High Court of Australia ruled that federal political

donations in Queensland were subject to Queensland’s political finance laws,

including its $1,000 disclosure threshold, and that all donations above the

$1,000 threshold must be disclosed under the Queensland donations disclosure

regime. The AEC Transparency Register currently lists 389 donations that have

been declared under the federal regime from returns from political parties

located in Queensland for the 2018–19 financial year, totalling some $3.4

million according to Library analysis. In contrast, the Electoral Commission of

Queensland’s donations register lists 2,745 donations that have been

declared under Queensland’s lower threshold disclosure regime for the same

period totalling $9.2 million. While some of these donations will be for state

purposes (and hence not required to be disclosed federally), given that there

was no Queensland state election in that period, some proportion will likely be

federal donations that were below the federal disclosure threshold and thus not

reported on federal returns.

The Spence decision leaves open the possibility that

other jurisdictions, almost all of which have much lower disclosure thresholds

than the federal scheme (see Table 3 below), could follow Queensland’s lead and

require federal donations to be disclosed under the state schemes also. This

would effectively circumvent the federal disclosure threshold, rendering it

arguably redundant. However, even in the absence of Queensland-like legislation

in the other jurisdictions, the significant discrepancies between the federal

and state/territory disclosure thresholds is likely to be a source of confusion

for donors.

3: Donation disclosure

thresholds in Australian jurisdictions

|

Federal |

NSW |

Vic. |

SA(a) |

Qld |

Tas.(b) |

WA |

ACT |

NT |

| Gift disclosure threshold |

14,000 |

1,000 |

1,020 |

5,381 |

1,000 |

N/A |

2 500 |

1,000 |

1,500 |

| Disclosure threshold indexed? |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

N/A |

Yes |

No |

No |

Note: Values as of February 2020, or the most recent as

published by the relevant authority.

(a) Applies to political parties that have opted into the SA

public funding scheme (all of the major and well-known minor parties at the 2018

state election).

(b) Tasmania currently relies on the federal political finance

regime and does not have a separate state regime.

Source: Parliamentary Library analysis of electoral commission

websites.

Appendix A: Total party receipts by

type by year (2006–07 to 2018–19)

| Financial Year |

Donations Received |

Other Receipts |

Public Funding |

Other/

unspecified(a) |

Undisclosed |

Total Receipts |

| 2006-07 |

25,915,879 |

25,961,659 |

13,328,352 |

3,125,238 |

66,937,227 |

135,268,355 |

| 2007-08 |

45,770,653 |

53,805,207 |

51,055,041 |

3,676,900 |

60,695,790 |

215,003,591 |

| 2008-09 |

20,112,894 |

18,689,424 |

6,150,224 |

4,171,638 |

49,591,036 |

98,715,216 |

| 2009-10 |

16,334,826 |

27,865,588 |

2,101,014 |

217,165 |

45,198,206 |

91,716,799 |

| 2010-11 |

40,680,523 |

53,917,969 |

65,647,667 |

29,176 |

67,851,659 |

228,126,994 |

| 2011-12 |

12,618,718 |

42,673,640 |

17,135,920 |

6,002,192 |

51,985,016 |

130,415,486 |

| 2012-13 |

20,605,174 |

38,182,296 |

19,106,322 |

0 |

76,277,040 |

154,170,832 |

| 2013-14 |

64,893,639 |

66,679,857 |

57,897,291 |

612,799 |

88,794,590 |

278,878,176 |

| 2014-15 |

29,544,318 |

53,814,265 |

31,809,694 |

1,374,650 |

67,195,956 |

183,738,883 |

| 2015-16 |

32,519,727 |

54,589,702 |

11,073,669 |

0 |

91,176,638 |

189,359,736 |

| 2016-17 |

14,572,348 |

54,834,739 |

79,103,793 |

74,990 |

59,986,159 |

208,572,029 |

| 2017-18 |

17,816,426 |

46,316,532 |

21,211,041 |

4,200 |

68,773,111 |

154,121,310 |

| 2018-19 |

130,925,969 |

98,809,831 |

90,211,667 |

138,082 |

114,721,179 |

434,806,728 |

| Total |

472,311,094 |

636,140,709 |

465,831,695 |

19,427,030 |

909,183,607 |

2,502,894,135 |

(a) Includes receipts listed as ‘subscriptions’, present in a

small number of returns, and receipts that were declared but were unclassified.

Note: The undisclosed amount was calculated by subtracting the

sum of the disclosed items from the total disclosed receipts, and does not

account for double-counting of intra-party transfers that may be listed as

other receipts. This means that the table likely underestimates the total

undisclosed amount.

Source: Parliamentary Library analysis of AEC data.