This brief provides some background data

on domestic and international economies. It includes summaries of recent

economic data, their underlying drivers, and discussion of the key issues and

concerns arising from interpretation of these data. The information in this

brief is designed to accompany the brief on the Pre-Budget Fiscal Outlook which

examines the domestic fiscal policy background and decisions.

Executive summary

- Most domestic indicators suggest the Australian economy is

growing less quickly:

- latest

National Accounts data show GDP growth of 2.3 per cent in the year to December

2018

- Consumer

Price Inflation was 1.5 per cent in the year to December 2018 (below the RBA

‘inflation target’ of 2-3 per cent, on average, over the medium term)

- wages

growth remains sluggish at 2.3 per cent through the year despite falling

unemployment

- although

total new capital expenditure was up 1.9 per cent through the year, dwelling

investment is expected to decline (dwelling approvals fell 28.6 per cent

through the year to January 2019)

- residential

property prices are falling, particularly in Sydney and Melbourne

- consumers

are ‘cautiously pessimistic’

- business

conditions and confidence have fallen

- the

monetary policy outlook is more ‘evenly balanced’ between a cash rate rise and

a cash rate cut

- Other domestic indicators offer a more positive outlook:

- unemployment

remains low and is expected to decline further

- the

terms of trade continue to grow (by 6.0 per cent through the year)

- commodity

prices (particularly iron ore, LNG and alumina) are strong

- Concerns about global growth have increased in recent months

prompting downward revisions:

- recent

financial market turbulence

- high

trade tensions between the US and China (and between the US and the Eurozone

for auto industries) affecting trade and investment intentions

- weaker

domestic demand, incremental policy easing and a decreasing current account

surplus in China

- rising

uncertainty, including around Brexit, social unrest in France, concerns about

Italy, political risks, protectionism

- falling

consumer confidence

- shifting

monetary policy rate expectations including inflation-induced policy tightening

(particularly in the US)

-

Some positive signs in global indicators:

- trade

war fears are dissipating

- a

delay in Federal Reserve tightening

- strengthening

emerging market economies

- falling

oil prices

Domestic outlook

This section provides data and commentary on key variables

which summarise the current and expected short term future state of the

Australian macro-economy. A review of key macroeconomic indicators is followed

by discussion of current areas of concern.

Table 1: Key macroeconomic indicators for Australia

| Gross Domestic Product

(GDP) growth (volume

measures, seasonally adjusted)[1] |

|

Source: ABS

|

GDP grew by 0.2 per cent in

the December quarter 2018 (2.3 per cent through the year), following a 0.3

per cent rise in the September quarter.

Compensation of employees

grew 0.9 per cent in the quarter (4.3 per cent through the year).

Quarterly household

consumption grew by 0.4 per cent in the quarter (2.0 per cent through the

year). The household savings ratio rose to 2.5 per cent.

Government final

consumption expenditure grew 1.8 per cent in the quarter (5.6 per cent

through the year) contributing 0.3 percentage points to GDP growth. This was

largely attributed to spending on disability, health and aged care services.

Private investment fell by

1.3 per cent in the quarter, driven by dwellings and ownership transfer

costs.

Net exports detracted 0.2

percentage points from GDP growth driven by a fall in exports.

Inventories held by

business increased by $685 million in the quarter.

The RBA’s central scenario

expects output growth of 3 per cent in 2019.[2]

Oxford Economics forecasts GDP growth of 2.2 per cent in 2019 and 2.7 per

cent in 2020.[3]

|

| Consumer Price Index (CPI) and Wage Price Index

(WPI) (percentage change from

corresponding quarter of previous year, all industries, seasonally adjusted)[4] |

|

Source: ABS

|

The CPI increased by 0.5

per cent in the December quarter 2018 (following a 0.4 per cent rise in the

September quarter), leading to a 1.8 per cent rise through the year.

The RBA expects

underlying inflation to ‘pick up over the next couple of years, with the

pick-up likely to be gradual and to take a little longer than earlier

expected. The central scenario is for underlying inflation to be

2 per cent this year and 2¼ per cent in 2020.’[5] Oxford Economics expect

the CPI to reach 2.5 per cent in 2020 and 2.7 per cent in 2021.[6]

In the December 2018

quarter, the all-sectors Wage Price Index rose by 0.5 per cent (the private

and public sector WPIs both rose by 0.6 per cent). Throughout the year, all

sectors rose 2.3 per cent.

(In original terms, rises

through the year ranged from 1.6 per cent for WA to 2.7 per cent for

Victoria.)

The RBA notes that ‘[t]he improvement in the labour market

should see some further lift in wages growth over time, although this is

still expected to be a gradual process.’[7]

Oxford Economics are forecasting wage growth of 3.1 per cent in 2020 and 3.6

per cent in 2021.[8]

|

| Private

capital expenditure (chain volume

measure, seasonally adjusted)[9] |

|

Source: ABS |

Total new capital

expenditure rose by 2.0 per cent in the December quarter 2018, up 1.9 per

cent through the year.

Buildings and structures

capital investment grew 3.2 per cent in the quarter (down 2.9 per cent

through the year); equipment, plant and machinery rose 0.7 per cent (up 8.1

per cent through the year).

Oxford Economics expect

business investment to rise by 2.2 per cent in 2019, but residential

construction will be a drag over the next couple of years.[10]

Dwelling investment is

expected to decline with falling pre-sales and tightening financial

conditions (dwelling approvals fell 28.6 per cent through the year to January

2019);[11]

business investment is expected to support growth; public investment is

supported by a large pipeline of infrastructure projects.[12]

|

| Terms

of trade (seasonally adjusted)

and commodity prices[13] |

|

Source: ABS and RBA |

The terms of trade grew by

3.1 per cent in the December 2018 quarter (by 6.0 per cent through the year).

The RBA notes that ‘[t]he terms of trade have increased over the

past couple of years, but are expected to decline over time’[14] as Chinese demand for

bulk commodities declines and other low-cost supply enters the market.[15]

In Australian dollar terms,

the Index of Commodity Prices increased by 4.6 per cent in February. The

Index has increased by 15.4 per cent through the year (led by higher LNG,

iron ore and alumina prices).[16] |

| Unemployment, underemployment and participation (per cent, seasonally adjusted)[17] |

|

Source: ABS

|

In January 2019, the

unemployment rate remained at

5.0 per cent; the participation rate increased by 0.1 percentage points to

65.7 per cent; the underemployment rate decreased 0.2 percentage points to

8.1 per cent.

Relative to January

2018, the unemployment rate fell 0.5 percentage points, the participation

rate is unchanged and the underemployment rate fell 0.6 percentage points.

The RBA expects a

‘further decline in the unemployment rate to 4¾ per cent ... over the

next couple of years’.[18]

Oxford Economics are forecasting unemployment of 5.0 per cent for 2020 and

4.9 per cent for 2021.[19] |

| Housing prices (year-ended growth, seasonally adjusted)[20] |

|

Source: ABS |

The Residential Property

Price Index (RPPI) for the weighted average of the eight capital cities fell

1.5 per cent in the September quarter 2018 (1.9 per cent through the year).

Melbourne property prices fell 2.6 per cent over the quarter; Sydney prices

fell 1.9 per cent.

‘Falls in Sydney and

Melbourne are no longer confined to the more expensive properties, with

declines now being observed in the middle and lower segments of the market.

Factors including tightening credit availability and falling property prices

are weighing on activity from both investors and owner occupiers.’[21]

RBA research suggests that

low interest rates explain much of the rapid growth in housing prices and

construction over the past few years.[22]

|

| The Westpac-Melbourne Institute Index of Consumer

Sentiment[23] |

Source: Westpac-Melbourne Institute |

The Consumer Sentiment Index

fell 4.8 per cent to 98.8 in March: consumers are ‘cautiously pessimistic’

(but still above the average level in 2017).

The deterioration was

largely attributed to the weak December quarter national accounts update and

housing market downturn.

Job loss concerns rose

sharply in March.

The Index of House

Price Expectations fell a further 2.7 per cent to 85.4 (a new low since

2009). Weakness remains pronounced in NSW and Victoria. |

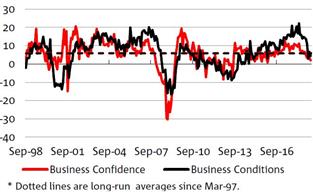

| NAB Monthly Business Survey[24] |

Source: NAB |

‘Conditions and

confidence fall – now both below average.’

The fall in business

conditions continues a relatively sharp decline over the previous six months;

although still positive, business confidence fell (and has been below average

since August 2018).

Retail remains the

weakest industry by a significant margin.

Conditions in trend

terms remain most favourable in the eastern mainland states. Capacity

utilisation (a measure of productive efficiency) is now below average;

overall survey measures of prices and inflation remain weak.

Small and Medium

Enterprise (SME) business conditions continued to decline in Q4 2018.

Confidence also declined and is now below average. Leading indicators

weakened further in Q4.[25] |

Monetary policy outlook ‘more evenly balanced’

In its latest Statement

on Monetary Policy (SMP), the RBA revised down its growth forecasts ‘in

light of recent data, particularly for consumption. GDP growth is expected to

be around 3 per cent over this year and 2¾ per cent over 2020.’[26] Forecasts for

underlying inflation were also revised ‘slightly lower’ reflecting

lower growth and ‘expected near-term weakness in administered and utilities

price inflation’.[27]

In a National

Press Club address in February, the Governor noted that, ‘[f]or some years,

growth in nominal aggregate household income has been unusually slow, averaging

just 2¾ per cent since 2016.’[28]

As a result, aggregate consumption has grown faster than income. The RBA

expects a pick-up in household disposable income to help offset the effects of

lower housing prices.

The RBA Governor says the chance of an interest rate cut is

now ‘more evenly balanced’ with the prospect of an increase:

If Australians are finding jobs and their wages

are rising more quickly, it is reasonable to expect that inflation will rise

and that it will be appropriate to lift the cash rate at some point. ... In the

event of a sustained increased in the unemployment rate and a lack of further

progress towards the inflation objective, lower interest rates might be

appropriate at some point.[29]

More recently, he has argued:

There are plausible scenarios under which the

next move in interest rates is up. There are also plausible scenarios under

which it is down. At the moment, the probabilities appear reasonably evenly

balanced.[30]

Some commentators have argued that ‘rising

funding pressures and deteriorating economic conditions will force the RBA to

slash cash rates’.[31]

ANZ has abandoned its previous prediction of two official interest rate

increases next year.[32]

In a move to increase transparency, the RBA

has begun to publish additional details on forecasts of key macroeconomic variables as at

the November 2018 Statement on Monetary Policy.[33] Comparing these numbers

with those in the December 2018 Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook

(MYEFO) shows that the RBA was more optimistic than the Government about future

GDP, consumption, exports and employment, but considerably less optimistic

about forecast growth rates for dwelling and business investment, imports and

the terms of trade.[34]

Governor Lowe has identified the following as areas to focus

on in 2019:

- a slowing in global growth with the Governor expressing ‘surprise

at some of the reaction to the lowering of forecasts for global growth, which

has been quite negative’

- the accumulation of downside risks including trade tensions

between the US and China, Brexit, the rise of populism, and ‘reduced

support from the United States for the liberal order that has supported the

international system and contributed to a broad-based rise in living standards’

-

the outlook for domestic household spending, which is closely

linked to the ‘correction’ in the housing market and the prospects for growth

in household income (in turn linked to employment and higher wages growth).[35]

In a speech on Climate

Change and the Economy by Deputy Governor Guy Debelle, he noted that ‘the

current drought has already reduced farm output by around 6 per cent and total

GDP by about 0.15 per cent’.[36]

He noted that the policy environment has a key effect, as well as the climatic

environment, on the changed environment that the economy will need to adapt to.

‘Both the impact of the [climate] shocks and the adjustment to those shocks

affect the macroeconomic trajectory.’[37]

Low wage growth

Continuing low wage growth has been a concern of

policymakers and the RBA for some time. The chart below (prepared by the

Commonwealth Bank) illustrates how wage growth has fallen, rather than

increased as forecast, in nearly every budget this decade.

The latest increase in the Wage Price Index, up 2.3 per cent

over the year in the December 2018 quarter, has been attributed to (i) a 3.5

per cent increase in the minimum wage for award-reliant workers and (ii) an

apparent acceleration of wage settlements in the (more highly unionised) public

sector.[38]

Figure 1: Budget forecasts versus reality,

wage growth 2007 to 2020

One recent study, The Wages

Crisis in Australia, identifies several potential

causes for the slowdown in wage growth:

- the decoupling of wage growth and labour productivity (due to

technological change, globalisation)

-

the increasing importance of the financial sector

- the weakening of workers’ collective bargaining rights and drop

in collective bargaining coverage and

-

increasing female participation combined with gender pay inequity

- public sector austerity policies (including downsizing, caps on

public sector wage growth)

- contracting out of social and community care services and

- increasing use of outsourcing and casual workers.[39]

The RBA Governor has cites both structural and cyclical

causes for lower wage growth:

- a downward revision of the ‘full employment’ level of

unemployment

- increasing underemployment (some part-time workers would like

more hours)

- higher levels of workforce participation

- changes in the bargaining power of workers and

- a focus on cost control in an environment of uneven diffusion of

technological progress.[40]

Falling house prices

According to the widely quoted CoreLogic Hedonic Home Value

Index, home prices fell 4.8 per cent in 2018.[41]

Housing values in in Sydney and Melbourne are predicted to fall 18‑20 per

cent from peak to trough in 2019.[42]

The RBA notes that the ‘current

correction in the housing market is a significant area of uncertainty’ with implications for the broader economy depending on how households

respond.[43] ‘Our economy is going through an adjustment

following the turn in the housing markets in our largest cities.’[44] The RBA Governor

noted that:

... unlike most other housing price corrections, this one has

not been associated with rising unemployment or higher interest rates. Instead,

mainly structural factors – relating to the underlying balance of supply and

demand – in our largest cities have been at work. The question is: what effect

will this change have on household spending?

... what we are seeing looks to be a manageable adjustment in

the housing market. It is not expected to derail economic growth.[45]

The Governor points to a number of factors as justification

for this argument:

- recent house price declines follow very large increases

- most households do not change their consumption in response to

short-term changes in their wealth, but take a longer-term perspective

- household income growth is expected to pick up (albeit gradually)

and ‘income growth usually matters more for consumption than changes in

wealth’.

However, he concludes:

Even so, given the uncertainties, we are paying very close

attention to how things evolve.[46]

Economic policy uncertainty

A team of US academics have devised a monthly index for Economic Policy Uncertainty.

The index for Australia is shown in Figure 2, along with a measure of global

uncertainty (a GDP-weighted average of national indices for 20 countries).[47] Although

uncertainty has increased slightly in Australia over recent months, it is well

below global values.

Another measure of economic risk gives Australia a score of 2.5 (low),

ranking it 5 out of 164 countries.[48]

Risk is unchanged from six months ago with downside risks related to: a

correction in the domestic housing market affecting residential construction

and consumer spending; China’s shift to slower, more balanced growth; and a

potential reversal of the recovery in commodity prices.

Figure 2: Economic policy uncertainty

Source: Economic

Policy Uncertainty.

International outlook

Table 2 summarises real GDP growth and inflation (CPI) data

and forecasts for 2017 to 2021 for selected international economies, focusing

on Australia’s top two-way trading partners in 2016‑17: China (23.8 per

cent of total), Japan (9.3 per cent), United States (9.0 per cent), Republic of

Korea (5.3 per cent) and the UK (3.7 per cent).[49]

Key drivers and risks for each economy are also identified.

Table 2: Real GDP growth and inflation in selected

international economies

| |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

| World |

| GDP

growth |

3.0 |

3.0 |

2.5 |

2.7 |

2.8 |

| Inflation

(CPI) |

3.0 |

3.2 |

3.1 |

3.2 |

3.1 |

| Drivers: consumer

confidence higher than two to three years ago (US and Japan), strong labour

markets (particularly in the US), lower oil prices, rising borrowing costs

may curb investment |

| Risks: escalation of

US-China trade war, no-deal Brexit, weak and volatile financial markets,

investment indicators weakening |

| Australia |

| GDP

growth |

2.4 |

2.8 |

2.2 |

2.7 |

3.0 |

| Inflation

(CPI) |

1.9 |

1.9 |

1.6 |

2.0 |

2.3 |

| Drivers: growth driven

by exports (LNG and services) and business investment, low interest rates |

| Risks: fall in

commodity prices, correction in domestic housing market, high household debt,

dependence on China, increasing trade policy tensions, slowing in capital

spending (government investment reaching a peak with end of NBN rollout),

weak consumer spending resulting from slow income growth |

| China |

| GDP

growth |

6.8 |

6.6 |

6.2 |

5.9 |

5.4 |

| Inflation

(CPI) |

1.5 |

2.1 |

2.0 |

2.3 |

2.6 |

| Drivers: expect

government stimulus measures, modest improvement in household consumption,

US-China trade war truce, easing financial and monetary policy |

| Risks: uncertainty

about trade conflict (fragile truce), slowing export growth, slowing

investment, weaker domestic demand, continuing focus on growth may compromise

reform program |

| Japan |

| GDP

growth |

1.9 |

0.8 |

0.7 |

0.3 |

1.0 |

| Inflation

(CPI) |

0.5 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

1.2 |

0.7 |

| Drivers: tight labour

market boosting consumption, government stimulus measures to soften impact of

tax rise, investment plans for large enterprises above long term averages,

investment boost from 2020 Tokyo Olympics, ‘no fiscal consolidation without

economic revitalization’, low interest rates |

| Risks: 2018 growth

affected by weather, weak export growth with slowing global trade,

consumption tax hike in Q4 2019, equity volatility, declining working-age

population, low productivity growth |

| |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

| United States |

| GDP

growth |

2.2 |

2.9 |

2.3 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

| Inflation

(CPI) |

2.1 |

2.4 |

1.6 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

| Drivers: strong labour

market fundamentals, rising earnings, strong consumer spending and

confidence, resilient business activity, firming government outlays |

| Risks: trade conflict

with China, government shutdown, ongoing political uncertainty, increasing

federal deficit, negotiations on debt limit ceiling, struggling housing

activity, tightening financial conditions |

| Republic of Korea |

| GDP

growth |

3.1 |

2.7 |

2.3 |

2.4 |

2.6 |

| Inflation

(CPI) |

1.9 |

1.5 |

1.2 |

2.1 |

2.1 |

| Drivers: pick up in

employment, front-loading of 2019 fiscal spending is expected to boost

employment and investment in eight key innovative sectors, relatively fast

pace of real labour earnings growth, subdued inflation, accommodative

monetary policy |

| Risks: slowing Chinese

and global demand (for semiconductors and petrochemicals) affecting exports,

weaker domestic demand, large rise in minimum wage, falling consumer

confidence, high household debt |

| United Kingdom |

| GDP

growth |

1.8 |

1.4 |

1.4 |

2.0 |

2.1 |

| Inflation

(CPI) |

2.7 |

2.5 |

1.9 |

1.7 |

1.6 |

| Drivers: low inflation,

looser fiscal policy, recovery in household spending |

| Risks: ‘disorderly’

Brexit plus sterling depreciation (and poor productivity performance), protectionist

trade policies slowing export growth, further cut in credit rating if public

finance improvement stalls |

| India |

| GDP

growth |

6.6 |

7.3 |

7.1 |

7.0 |

6.9 |

| Inflation

(CPI) |

3.3 |

3.9 |

4.2 |

5.4 |

5.4 |

| Drivers: lower oil

prices, more accommodative monetary conditions likely (new governor of RBI),

smaller drag from net exports, reduced impact of demonetisation in November

2016 (estimated cost 1.5 per cent of GDP) and GST imposition (came into

effect July 2017), Moody upgraded credit rating in 2017, unit labour costs

among lowest in BRIC economies |

| Risks: reduced lending

ability of non-banking financial sector may affect overall credit

availability and delay business investment plans, slowdown in private

consumption, reform momentum (on land, labour, power and education) likely to

slow as 2019 elections approach |

| Eurozone |

| GDP

growth |

2.5 |

1.8 |

1.3 |

1.5 |

1.4 |

| Inflation

(CPI) |

1.5 |

1.8 |

1.3 |

1.5 |

1.6 |

| Drivers: exports more

resilient than expected in Q4 2018, ECB dovish, strong growth in output, confidence

and private consumption in Spain, continuing growth in employment, easing

inflation |

| Risks: sharp slowdown

in Germany, fall in manufacturing activity, weak services activity, weakness

in forward-looking indicators, political risks, tensions in financial markets,

weaker world trade (especially China), threat of US tariffs on European cars,

political uncertainty and falling sentiment in Italy |

Source: Oxford Economics, Global Data Workstation, accessed 13

March 2019.

Global growth outlook

Concerns about global growth have increased in recent

months, largely attributable to:

- recent financial market moves

-

trade tensions between the US and China

-

uncertainty surrounding Brexit

- the degree to which Chinese policymakers can fine-tune growth to

prevent further economic weakness

- soft growth in the Eurozone, especially Germany and Italy and

-

inflation-induced policy tightening and the phasing out of

unconventional monetary policies which could trigger unintended liquidity

shocks.

The January update of the IMF World

Economic Outlook revised down estimates of global growth to 3.5 per

cent in 2019 and 3.6 per cent in 2020 (0.2 and 0.1 percentage points below

October projections).[50]

This was attributed to ‘softer momentum’ in the second half of 2018

(particularly in Germany, Italy and France), weakening financial market

sentiment and a deep contraction in Turkey. Potential triggers for

deteriorating risk include escalating trade tensions, a no-deal Brexit and a

‘greater-than-envisaged’ slowdown in China.

Across all economies, measures to boost potential output

growth, enhance inclusiveness, and strengthen fiscal and financial buffers in

an environment of high debt burdens and tighter financial conditions are

imperatives.[51]

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and

Development OECD Interim Economic Outlook notes that

global growth is weakening as ‘some risks materialise’.[52] These risks include

vulnerabilities in China, Europe and financial markets. Real world GDP growth

estimates have been revised down (since November 2018) to 3.3 per cent in 2019

and 3.4 per cent in 2020. A decline of 2 per cent in domestic demand growth in

China for two years is estimated to reduce world GDP growth by more than 0.5

per cent. Euro area growth could be hit by a weak UK economy as the uncertainty

around Brexit continues.

However, RBA Governor Philip Lowe has stated

that ‘... while some of the downside risks have increased, the central scenario

for the world economy still looks to be supportive of growth in Australia’.[53]

These risks include trade tensions between the

US and China, Brexit, the rise of populism, reduced support from the US for

long-standing international agreements, and adjustments in China as the

authorities aim to reduce shadow financing. If economic activity in

China responds ‘less vigorously’ to recent fiscal and monetary policy measures,

Chinese growth could be weaker than forecast.

An advanced economy monthly growth indicator—which summarises

information from high-frequency data—fell in January, recording its sharpest monthly

drop in seven months.[54]

The leading indicator is a GDP-weighted average of 5-7 activity indicators for

20 advanced economies. The results suggest there is ‘little sign yet of a

rebound in growth momentum’. In levels terms, the index remained above the 2016

low point, suggesting a gradual loss of momentum in early 2019.

Financial market turbulence

In its latest Quarterly Review,

the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) attributed recent financial

market turbulence to ‘a reminder of the narrow path that central banks are

treading in their quest for policy normalisation, in a generally challenging

policy environment.’[55]

[U]ncertainty that surrounds the unprecedented

monetary policy normalisation process no doubt makes markets more sensitive to

such developments.[56]

In December 2018, BIS concluded that:

... the market tensions we saw during this

quarter were not an isolated event. As already noted on previous occasions,

they represent just another stage in a journey that began several years ago.

Faced with unprecedented initial conditions - extraordinarily low interest

rates, bloated central bank balance sheets and high global indebtedness, both

private and public - monetary policy normalisation was bound to be challenging

especially in light of trade tensions and political uncertainty. The recent

bump is likely to be just one in a series.[57]

High trade tensions

Trading partner growth is expected to remain around trend in

2019 and 2020 but trade tensions ‘remain high’ and escalation continues to be a

significant risk.[58]

As at 4 March 2019, trade talks between the US and China on tariff increases

were still underway. Possible increases in US automotive tariffs or stricter

quotas remain a concern, in particular for Germany and Japan. There is evidence

that trade tensions are having adverse economic effects on trade and investment

intentions, and are increasing uncertainty about the growth outlook for many

economies.[59]

The undulating prospects of trade talks with China and

concomitant reactions in the markets provide a stark reminder that

protectionist policies represent a major threat to the growth outlook.[60]

Bank of England calculations suggest that world GDP could

fall by 2.5 per cent (over three years) following a 10 percentage point

increase in tariffs between the US and all of its trading partners (assuming

business confidence and financial conditions are also affected).[61]

By one estimate, a dramatic increase in trade policy tensions between

the US and Asia could slow Australian growth to below 2 per cent in 2019 and

2020.[62]

Political and policy uncertainty

Political uncertainty could dampen the global growth

outlook, particularly investment and consumption in the UK with Brexit

uncertainty; social unrest in France with resulting policy changes; and

increasing concerns about economic and fiscal policies in Italy.[63]

Figure 2

(on page 11) makes clear the recent increase in global uncertainty.

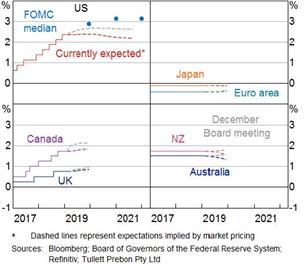

Shifting monetary policy rate expectations

Policy rate expectations have shifted globally, particularly

in the United States (see chart below). This has been attributed to reduced

expectations for growth and inflation, increased concerns about downside risks

and higher corporate risk premiums.[64]

Figure 3: Policy rate expectations

Source: C Kent, ‘Financial conditions and the

Australian dollar – recent developments’, address to XE Breakfast

Briefing, Melbourne, 15 February 2019. (The FOMC is the Federal Open Market

Committee is the monetary policymaking body of the Federal Reserve System.)

In a speech

on 12 February, Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England, noted that ‘global

momentum is now weakening in all major regions and downside risks have

intensified’.[65]

He attributed the deceleration to tighter financial conditions, rising trade

tensions and growing policy uncertainty. In Monetary Policy Committee

projections, ‘the balance of headwinds to growth and more accommodative policies

are expected to return global growth to around potential rates by the end of

the year’.[66]

Moderating growth in the United States

The US Federal Reserve is expected to pause its

tightening policy early in the year with rates not expected to rise until later

in the year or even until 2020.[67]

A partial US government shutdown and slowing global growth has added to the

headwinds, but NAB estimates that while growth may move modestly below trend

for a period, recession fears—at least in the short term—are overblown.[68]

Some concerns have been raised about the independence and

legitimacy of the US Federal Reserve as it comes ‘under fire’ from President

Trump.[69]

Mr Trump publicly criticised the Federal Reserve for raising its benchmark

interest rate.

If the Fed’s independence, or more likely its legitimacy, is

compromised, other branches of government could leverage their newfound

influence to ensure favourable short-term economic outcomes, resulting in

higher risks of inflation and ineffective monetary policy in the future.[70]

The RBA expects growth in the US to moderate partly as the

effects of recent fiscal stimulus begin to wane and as monetary policy becomes

less accommodative. The US Government shutdown during December and January is

expected to affect growth in the first part of 2019.[71]

The US accounted for 9.0 per cent of two-way trade with

Australia in 2016-17. The impact on Australia of a US slowdown will also depend

indirectly on the response by both the US and China to trade hostilities.

China slowdown

The slowdown in China is broad-based, across investment,

consumption and exports. The trade conflict with the US remains ‘a wild card’

with underlying tensions between the US and China hanging over business

activity and sentiment.[72]

Weaker domestic demand, incremental policy easing and a decreasing current

account surplus are expected to affect growth in the short term.

Household debt levels are elevated by emerging market

economy standards, but China’s overall private debt ratio stopped rising last

year in response to official action to curb shadow banking.

A controlled deceleration in growth is more likely.[73]

China recently announced additional stimulus measures to

support its economy:

While exact details of the stimulus package are yet to be

unveiled, the Chinese finance ministry suggested the measures would include

cutting value added tax for some companies, particularly in the manufacturing

sector, as well as rebates for other businesses to ward off a more damaging

slowdown. Some estimates we have seen this morning suggest the fiscal stimulus

could be worth in the order of 1% of GDP.[74]

A recent academic study on the impact of China’s slowdown on

Australia’s growth concluded that the effect on Australia of a permanent fall

in China’s growth rate from 10 per cent to annum to 7 per cent per annum

would be to reduce Australia’s growth rate by about 0.2 percentage points in

the short run and approximately 0.5 percentage points in the long run.[75]

Brexit uncertainty

There is still considerable uncertainty around Brexit. On 25

November 2018, UK and EU leaders approved the text of a

treaty-level Withdrawal Agreement and political declaration on the future EU-UK

relationship. The Withdrawal Agreement includes a transition period running

from 29 March 2019 to 31 December 2020, with the possibility of a one or

two-year extension. However, this Withdrawal Agreement has, to date, been

rejected (twice) by Parliament.[76]

Uncertainty over Brexit has fueled global

economic uncertainty, leading to consumers cutting back on spending, businesses

streamlining, closing or relocating, and financial markets demanding greater

risk premia to lend. Brexit will not allow the UK to benefit from the terms of

any free trade agreement between the EU and Australia. And negotiations for a

separate UK-Australia agreement can only start after Brexit is formalised.[77] After the initial impact

on financial markets following the Brexit vote in 2016, the economic impact of

a ‘no-deal’ Brexit is most likely to affect Australia through the UK’s

contribution to global economic growth.

Global risks

According to one survey, business gloom about the global

economy has continued to increase, with more businesses judging that the

probability of a sharp slowdown has increased over the past few months than at

any time since the start of the survey three years ago.[78]

Around 70 per cent of respondents think that the probability of a sharp

slowdown has increased, with trade concerns dominating in the short term. A key

emerging downside risk is perceived to be the Chinese economy. Over the next

five years, protectionism is viewed as a significant risk, along with a hard

landing in China, the global rise of populism and a break-up of the EU. Short-term

upside risks include a dissipation of trade war fears, strengthening emerging

market economies, delayed Federal Reserve tightening and falling oil prices.[79]

The impact on Australia of a US-led trade war—which has a

significant negative impact on China and the rest of the Asia-Pacific region—has

been estimated to slow GDP growth to around 1.0 per cent in 2020.[80] There is likely

to be a more limited impact on the Australian economy from faster Federal

Reserve tightening and a no-deal Brexit.[81]

As at January 2019, the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU)

negative global risk scenarios included:

- a US-China trade conflict turning into a full-blown global trade

war (moderate risk, very high impact)

-

supply shortages leading to a globally damaging oil-price spike

(moderate risk, high impact)

- faster than expected US monetary tightening triggering a global

slowdown (low risk, very high impact)

-

a disorderly and prolonged economic downturn in China (low risk,

very high impact)

- a major military confrontation on the Korean peninsula (low risk,

very high impact)

- proxy conflicts in the Middle East disrupting global energy

markets (moderate risk, moderate impact)

- cyber-attacks and data integrity concerns (moderate risk,

moderate impact)

- territorial disputes in the South China Sea leading to an

outbreak of hostilities (low risk, high impact)

- political gridlock leading to a disorderly no-deal Brexit (very

low risk, low impact).[82]