Issue

Critical minerals are essential to modern and advanced

technologies, including computers, heavy industry, defence, and renewable

energy. However, these commodities are exposed to risks of supply chain

disruption or bottlenecks, a feature which makes them ‘critical’.

Reducing these constraints is a focus for strategic

international partnerships to support economic growth and national security.

Australia is a global leader in mining and exporting raw

materials, including some critical minerals. Australia does not have a

well-developed capability for processing or value-adding to these raw

materials.

This paper presents an overview of critical minerals, and

Australia’s resources, potential, and current policy settings.

Key points

- Many

countries (including Australia) maintain sovereign critical minerals lists.

- Australia

is richly endowed with mineral resources and is a major exporter of raw

materials with well-established trading partners.

- It

is also an attractive investment destination, with a range of funding and

support mechanisms to foster critical minerals development.

- Australia

currently lacks a well-developed value-adding capability for critical

minerals and their products but is looking to increase this capability.

Context

Critical

minerals are defined as those that are essential for modern technologies,

the economy, or national security and have supply chains exposed to risk or

disruption. It is this significant exposure to supply chain risk that

differentiates critical minerals from strategic

minerals.

Different countries use different approaches

to define critical minerals or ‘criticality’ (p. 1,019). These generally

include an assessment of economic importance weighted against a measure of

vulnerability. Often, vulnerability relates not just to the source of a

mineral’s primary ore or its global distribution but also factors related to

the supply chain, such as processing locations. Other assessments may recognise

vulnerability as it relates to specific uses, such as defence. Each country has

its own needs and vulnerabilities, and therefore, their critical minerals lists

may vary.

Australia’s trading partners, such as the USA,

UK, Canada,

India,

New

Zealand, South

Korea and the EU

each have their own critical minerals lists. Additionally, in 2024, NATO published

its own list of 12 defence-critical raw materials. It is important to note that

these lists can change

over time as supply, technological, industrial and geopolitical conditions

vary (pp. 1,019–1,020). Importantly, supply chain vulnerabilities can be

heightened in uncertain geopolitical or trade environments.

Australia’s approach to critical minerals

Australia’s Critical

Minerals Strategy 2023–2030 sets out how critical minerals are defined

and examines how their development and supply can be supported and secured. The

related Critical

Minerals List identifies 31 critical minerals [see Box 1], which satisfy a four-part

test:

- are essential

to our modern technologies, economies, and national security, specifically

the priority technologies set out in the Critical Minerals Strategy

(p. 16), linked to the List

of Critical Technologies in the National Interest

- for which

Australia has geological potential for resources

- are in demand

from our strategic international partners

- are

vulnerable to supply chain disruption.

The Critical Minerals list will be reviewed at

least every 3 years, as recommended by the Critical Minerals Strategy (p.

44). The Minister for Resources is also able to review and update the list to reflect

‘global strategic, technological, economic or policy changes’. The Critical

Minerals List has been updated over time, with nickel

being added to the list in February 2024, after additional updates

in 2023. Mineral commodities listed as critical minerals are eligible for

various government supports and funding, including projects seeking to mine,

process, or value-add.

Some of the applications that use critical minerals are

provided in Table 1. Note, this list of uses is not exhaustive, and is focused

on minerals for which Australia has significant production or reserves.

Table 1 Some of Australia’s

critical minerals and their uses

| Critical mineral |

Traditional and

defence uses |

Clean energy

applications |

|

Antimony

|

Alloys

|

Solar PV panels

|

|

Cobalt

|

Superalloys

Device batteries

|

EV batteries

|

|

Graphite

|

Foundry applications

High-temp lubricants

Composite materials

|

Lithium battery anodes

|

|

Lithium

|

|

EV batteries

Battery energy storage systems

|

|

Magnesium

|

Lightweight alloys

Steelmaking purposes

|

-

|

|

Manganese

|

Alloys

|

EV batteries

|

|

Nickel

|

Stainless steel

|

EV batteries

|

|

Rare earth elements

|

Glass, lights

Magnets

|

Wind turbines

EV motors

|

|

Silicon

|

Computing chips

|

Solar PV panels

|

|

Titanium and mineral sands

|

Specialised alloys

Pigments

|

Specialised alloys

Pigments

|

|

Tungsten

|

Alloys

Cutting tools

|

Permanent magnets in EVs/wind

turbines

|

|

Vanadium

|

Steel alloys

Sulphuric acid production

|

Vanadium flow batteries

|

Notes: Defence uses mainly include use in alloys.

Source: Compiled by the Library from Department of Industry,

Science and Resources (DISR), Resources and

Energy Quarterly March 2025, (Canberra: DISR, 31 March 2025), 106

(nickel), 122 (lithium), and 128 (others).

Australia’s role: quarry,

factory, or end-user?

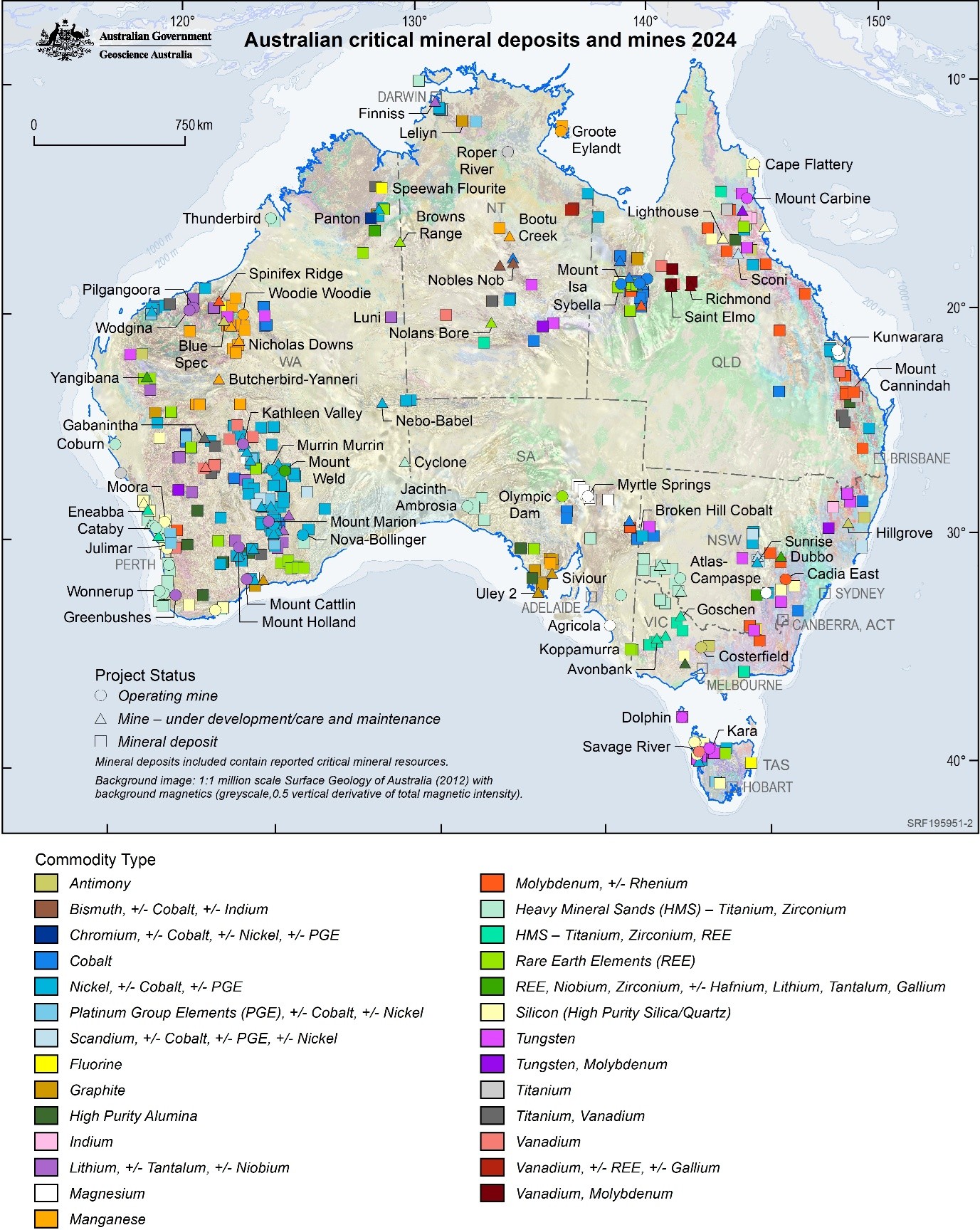

Australia

hosts globally significant deposits of critical minerals distributed

across the country (Figure 1). It is also a major global exporter of some

critical minerals, having in 2023 produced 49% of the

lithium, 9% of the manganese, 24% of the zircon, and significant proportions of

cobalt, rare earths, and other critical minerals.

The Critical Minerals Strategy states that ‘growing the

[critical minerals] sector and moving into downstream processing, where we

can do so competitively, will capture more value, economic benefits and jobs in

Australia while boosting our sovereign capability’ (p. 12). However,

despite Australia’s established raw material export successes, moving into

processing and manufacturing (and the broader economic impacts), is less

certain.

A key aspect will likely require fostering investment in

critical minerals, which can secure supply for both the domestic market and key

trade partners. Placing a commodity on the Critical Mineral List is a key

driver in fostering industry interest, which in turn drives growth in

Australia’s identified resource base. The trade-off is that industrial

policy can introduce economic distortions and inefficiencies and may ‘crowd-out’

other sectors in the economy.

Figure 1 Australia’s

critical mineral deposits and mines 2024

Source: Australian

Critical Minerals Map 2024 – A4 version from J. Pheeney and C. Kucka, Australian Critical

Minerals Map 2024 (6th Edition), Scale 1:5,000,000,

(Canberra: Geoscience Australia, January 2025). A higher

resolution, more detailed large-format PDF of this map is available.

Critical minerals funding,

support, and research

Government research and development support allows agencies

to carry out precompetitive activities such as data collection and modelling,

and reassessing existing data. Current initiatives include:

International partnerships

Australia has entered into agreements with the USA,

Canada,

UK,

Japan,

India,

Germany,

and the EU

to streamline critical mineral resources development. This includes mining and

ore production, mid-stream processing and export arrangements. The Department

of Industry, Science and Resources also lists other examples

of bilateral and multilateral international arrangements relating to the

critical minerals sector.

Conclusion

A comprehensive

review of the Critical Minerals Strategy is expected in 2026 (p. 12).

Australia is in the early stages of growing its critical minerals sector. While

exploration and mining continue to grow, mid-stream processing and down-stream

manufacturing are not yet developed. Agreements with international partners may

help ensure stable supply chains internationally. This may be bolstered by the

Australian Labor Party’s 2025 federal election commitment

to create a critical minerals strategic reserve. However, it remains to be seen

how government support will translate into economic activity, domestic growth and

supply chain certainty for critical minerals.

Further

Reading

- Australian

Critical Minerals Prospectus, Australian Trade and Investment Commission

-

Annual publication summarising advanced critical minerals projects.

- Resources

and Energy Quarterly (REQ) series, Department of industry, Science and

Resources (DISR)

- This

series provides information and outlooks for a range of energy and mineral

commodities and examines Australian production and trade in a global context.

- A.

Hughes, A. Britt, J. Pheeney, A. Morfiadakis, C. Kucka, H. Colclough, C.

Munns, A. Senior, A. Cross, A. Hitchman, Y. Chen, J. Walsh and A. Jayasekara,

Australia’s Identified Mineral

Resources 2024, (Canberra: Geoscience Australia, 27 February

2025).

- Most

recent annual assessment of Australia’s mineral reserves and resources for

all major and some minor commodities, including critical minerals.

- International

Energy Agency (IEA), The

Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions, (Paris: IEA,

2021).

- Analysis

of links between critical minerals and the energy transition.

- IEA,

Global

Critical Minerals Outlook 2025, (Paris: IEA, May 2025).

- A

snapshot of recent industry developments with medium- and long-term supply

and demand outlooks. Assesses broad risks to critical minerals supply chains.

- Nedal

T. Nassar and Steven M. Fortier, Methodology

and Technical Input for the 2021 Review and Revision of the U.S. Critical

Minerals List, US Geological Survey (USGS) Open-File Report 2021-1045

(Reston, VA: USGS, 2021).

- Detailed

discussion of the US approach to assessing critical minerals, including a

background on policy development.

Relevant Parliamentary Library Publications

- Dr

Becky Bathgate, ‘New

industrial policy: a Future Made in Australia’, Budget Review Article

2024–25, (Canberra: Parliamentary Library, 25 June 2024).

- Dr

Becky Bathgate and Ian Zhou, ‘Future

Made in Australia Bill 2024 [and] Future Made in Australia (Omnibus

Amendments No. 1) Bill 2024’, Bills Digest, 6, 2024–25, (Canberra:

Parliamentary Library, 9 August 2024).

- Scanlon

Williams, ‘Future

Made in Australia (Production Tax Credits and Other Measures) Bill 2024’,

Bills Digest, 46, 2024–25, (Canberra: Parliamentary Library, 30

January 2025).