The 2022–23 Budget contains several

key measures in vocational education and training (VET), with

significant funding allocated to apprenticeship incentives and skills reform.

However, the new spending measures will not significantly

offset a rapid decline in Australian Government expenditure on VET over the

forward estimates, driven by the cessation of temporary measures in response to

COVID-19, as well as several funding agreements with states and territories.

Funding trends

Australian Government VET expenditure consists of:

Budget strategy

and outlook: budget paper no. 1: 2022–23 (pp.

150 and 168) shows total VET funding is estimated to peak at approximately $7.1

billion in 2021–22 and fall to $4.2 billion by 2025–26.

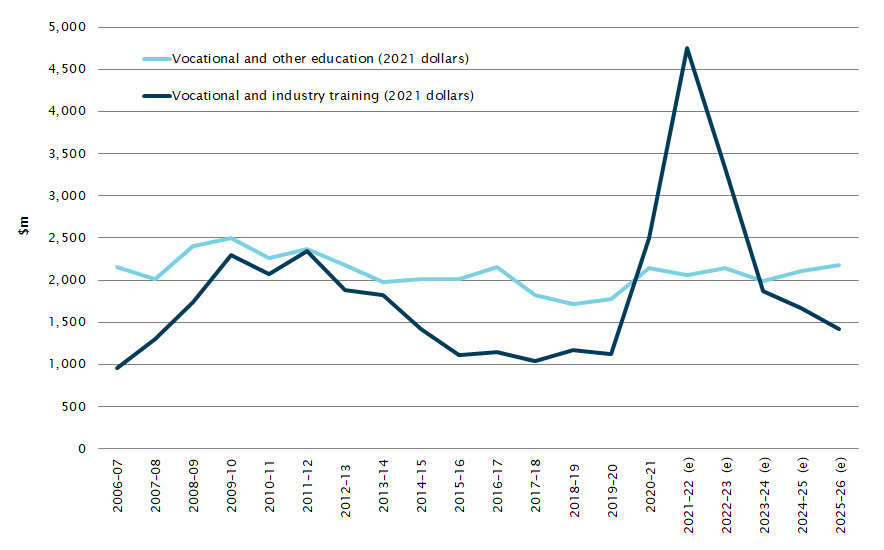

Parliamentary Library analysis (Figure 1 below), based

on Budget paper no. 1: 2022–23 (pp. 150 and 168) and Final

budget outcome papers over 20 years, indicates that in 2025–26, VET funding

will be approximately $3.6 billion in real terms. This is above the level of

investment that was in place immediately before the pandemic, when real funding

was $2.9 billion per year from 2017–18 to 2019–20. However, it is still below the

level of the last substantial increase in Australian Government VET investment

between 2008–09 and 2012–13.

Figure 1 Australian Government estimated expenditure on vocational education and training, 2006–07 to 2025–26 ($ million)

Source: Parliamentary Library,

based on Australian Government, Budget Strategy and Outlook: Budget Paper No. 1:

2022–23; Australian Government, Final

budget outcome, various years.

Note: real funding has been

calculated by the Parliamentary Library by deflating the nominal expenditure

figure by the June quarter CPI and CPI forecasts from the 2022–23 Budget. This

methodology may differ to that presented in the Budget papers. ‘(e)’ means that

figures are budget estimates.

Skills reform

Consistent with previous years, approximately $1.6 billion per

year has been provided over the forward estimates for the National Skills and

Workforce Development SPP (Budget paper no. 3: 2022–23, p. 45).

All other funding to the states and territories for skills

and workforce development is scheduled to conclude between 2022 and 2024:

Rather than funding a large-scale extension of JobTrainer,

or a new National Partnership Agreement to replace the SAF, in this Budget the

Government has allocated an additional $3.7 billion over 5 years from 2022–23

(and $284.6 million per year thereafter) to work with states and territories on

a new National Skills Agreement to replace the NASWD (Budget

paper no. 2: 2022–23, pp. 78–79). The additional funding is only available if the states and

territories can reach agreement.

The NASWD was reviewed

in 2020 by the Productivity Commission (PC). The final

report, released in January 2021, found that the NASWD is overdue for

replacement. The PC made many far-reaching recommendations, including more

focus on competition, and using the National

Skills Commission’s work on efficient costs and loadings as

a basis for common course subsidies (which are currently set by state and

territory governments and can vary considerably).

All governments agreed to a new Heads

of Agreement for Skills Reform in August 2020, under which JobTrainer funding

was provided. However, although at the time of the 2021–22

Budget a new National Skills Agreement was expected

to follow the Heads of Agreement by August 2021 (Federal

financial relations: budget paper no. 3: 2021–22, p. 43), negotiations

have been a source of contention. Skills ministers from 6 states and

territories have reportedly

written to Stuart Robert, Minister for Employment, Workforce, Skills, Small and

Family Business, ‘expressing “strong concern” and “dismay” over the

government’s insistence on pushing a draft agreement that was rejected by all

states and territories last year’. Among the concerns reportedly expressed were

potential reductions in funding to TAFEs, increased course fees, and the

proposed role of the National Skills Commission in setting prices and

subsidies.

Although the new Agreement is now expected to be ‘finalised

in the first half of 2022’, the experience of the SAF (which saw plans

progress without Victoria and Queensland) suggests such agreements will not

necessarily be accepted, despite the associated funding.

The national VET regulator

The national VET regulator, the Australian Skills Quality Authority (ASQA) has

also been allocated an additional $28.5 million over 5 years from 2021–22 as

part of the VET reform package (Budget

paper no. 2: 2022–23, pp. 78–79), to establish

assurance functions. On 22

March, the Government announced that ASQA would

take on responsibility for quality assurance of training

packages from 1 January 2023 to 31 December

2024. A post-implementation review of new industry engagement arrangements will

be undertaken ‘to assess whether the system is working as intended’, with

ASQA’s continued responsibilities subject to the outcomes of this review.

This change is part of broader

changes to industry engagement in the VET system,

which build on the 2019 Strengthening skills

expert review of Australia’s vocational education and training system

(the Joyce Review). While the Joyce Review did not envisage ASQA taking on

training package assurance, it did find (pp. 57–58) that the existing process, which

is complex and ‘overly-centralised’, can take several years, meaning ‘training

packages can be out of date before they even start to be taught’.

This function has already been conferred on ASQA by

a legislative instrument.

Employment services

The Budget includes a relatively small amount of funding for

employment services-related measures. The most substantive of these is a new

pre-employment program entitled ReBoot, which is targeted at young people who

are not engaged in education, employment or training (NEET) (Budget paper no.

2: 2022–23, p. 74).

Under the initiative, which was announced

on 19 March, an estimated 5,000 disadvantaged people aged 15 to 24 will

participate in ‘tailored, community-focused early interventions’ of up to 12

weeks. The interventions will involve things such as hands-on learning

activities, mentoring and work experience, and ideally provide a pathway to

employment and training. The interventions are to be delivered by ‘expert

not-for-profit organisations’ selected through a competitive procurement

process. Funding of $52.8 million over 5 years from 2021–22 has been

allocated towards the ReBoot initiative, and it is expected to be rolled out

‘in early 2023’.

While the initiative is small, it is intended to complement

other youth employment programs, with the most relevant of these being the Transition to Work program,

which is also targeted at young people who are at high risk of long-term

unemployment and welfare dependency.

The ReBoot initiative will, along with the Transition to

Work program, form part of the new employment

services model, entitled Workforce Australia, that is to

replace the jobactive program. Workforce Australia will commence

from 1 July 2022.

Stakeholder response and concluding

comments

In contrast to employer subsidies for apprentices, which

have seen substantial growth as part of the Government’s response to the

COVID-19 pandemic, as discussed

elsewhere in this Budget review, broader support for learners in the

VET system and through employment services programs is relatively modest.

Training sector stakeholders including TAFE

Directors Australia and the Independent

Tertiary Education Council Australia, as well as employer groups such as

the Australian

Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Ai

Group, and the Business

Council of Australia have welcomed additional funding for skills, pointing

to the potential for a new National Skills Agreement to further support skills

development.

However, although Commonwealth funding to the states and

territories for skills and workforce development is projected to remain stable

over the forward estimates, while apprenticeship funding will fall sharply, the

bulk of new funding for VET reform in this Budget depends on finalising an

intergovernmental agreement that is already delayed and highly contested.

All online articles accessed April 2022