CHAPTER 2

THE EXTENT AND CAUSES OF HEARING IMPAIRMENT IN AUSTRALIA

One in six Australians is affected by hearing loss...With an

ageing population, [this] is expected to increase to one in four...by 2050.

Access Economics, Listen Hear! The economic impact and cost of

hearing loss in Australia, (February 2006), p. 5.

The most common causes of hearing loss are ageing and

excessive exposure to loud sounds. The effects of age and noise exposure are

additive so that noise exposure may cause hearing loss in middle age that would

not otherwise occur until old age.

Department of Health and Ageing, Submission 54, [p. 1].

Introduction

2.1

The increasing prevalence of hearing loss is due largely to an ageing

population, although there are a range of factors and behaviours among other

sectors of the population which will have a flow-on effect on people's hearing

in later life. These factors will be canvassed in this chapter.

2.2

This chapter will consider the causes of hearing loss, aspects of the

severity and impacts of different levels of hearing loss, and the current and

projected prevalence of hearing loss in Australia.

2.3

The committee drew on evidence from hearing loss experts and from people

with hearing loss themselves. In addition, Access Economics' report Listen

Hear! was of great value to the committee in considering the issues raised

in this chapter.

Severity of hearing impairment

2.4

This section summarises some of the language and concepts around the

severity of hearing loss. This will assist the reader to understand the evidence

which follows about prevalence and causes of hearing loss.

2.5

There are a range of facets to hearing loss, including:

- decreased audibility, where people with hearing impairment do not

hear some sounds at all, depending on the severity of hearing loss. As a

consequence, a person may be unable to understand speech, as some essential

parts are inaudible;

- decreased dynamic range. The dynamic range of an ear is the level

of difference between the threshold of audible sound and the threshold of loudness

discomfort. A person with a hearing impairment will have a smaller dynamic

range than that of a person with normal hearing;

- decreased frequency resolution. A person with hearing impairment

may have difficulty separating sounds of different frequencies. A person with

normal hearing is able to separate speech from background noise; however a

hearing impaired person is unable to differentiate between speech and noise

where the frequencies are close together. This can also affect the

intelligibility of speech in some cases; and

- decreased temporal resolution. Intense sounds can mask weaker

sounds that immediately precede or follow them, and inability to perceive the

weaker sounds adversely affects speech intelligibility. The ability to hear

weak sounds during fluctuating background noise gradually decreases as hearing

loss worsens.[1]

In combination, these deficits can cause a reduction in

intelligibility of speech for a hearing impaired person compared to a

normal-hearing person in the same situation.

2.6

Hearing levels are determined by testing the range of sounds that can be

heard and how softly one can hear such sounds. The range of sounds is measured

in hertz (Hz) or waves per second and the intensity or strength of sound is

measured in terms of a scale of decibels (dB).[2]

2.7

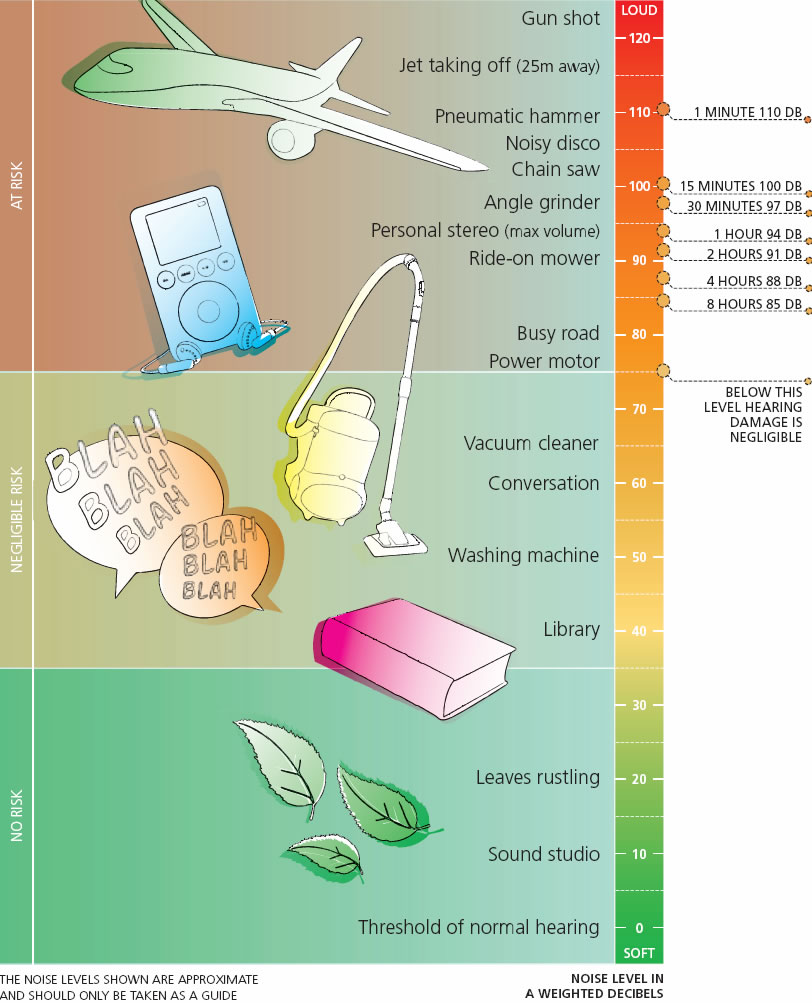

Figure 2.1 is a visual representation which equates different decibel

levels with common noises.

Figure 2.1: Approximate sound

levels (dB) for common types of noise exposure

Figure by Australian Hearing, provided in DOHA, Submission 54, p.

16.

2.8

The severity of hearing loss is categorised as mild, moderate, severe,

or profound, depending on how loud a sound has to be before a person can hear

it. The severity of hearing loss is categorised differently for different age

groups.[3]

Table 2.1: Severity of hearing loss

by decibel range and age

|

Severity of

hearing loss |

Decibel

(dB) range

(<

15 years) |

Decibel

(dB) range

(≥

15 years) |

|

Mild |

0-30dB |

≥25dB and

<45dB |

|

Moderate |

31-60dB |

≤ 45dB

and <65dB |

|

Severe |

61-90dB |

≥ 65dB |

|

Profound |

≥ 91dB |

|

Source: Access Economics, Listen

Hear! The economic impact and cost of hearing loss in Australia, (February

2006), p. 5.

2.9

Hearing loss is measured using either subjective tests, such as

audiometric testing, or objective tests, which measure a physiological response

from the individual. Newborn hearing tests are objective tests which use an

auditory brain stem response technique to an acoustic stimulus.[4]

The extent of hearing impairment in Australia

2.10

Access Economics reported extensive data on the prevalence of hearing

loss amongst Australians. In 2005 around 3.55 million Australians had some

hearing loss. Of these, some 99.7 per cent were aged 15 years or older.[5]

Prevalence of hearing impairment in

children

2.11

Australian Hearing submitted that 'between nine and 12 children per

10,000 live births will be born with a moderate or greater hearing loss in both

ears'. In addition, three to four children per 10,000 live births will be born

with moderate hearing loss, and a further 23 per 10,000 will acquire a hearing

loss that requires hearing aids by the age of 17.[6]

This evidence suggests that 39 children in 10,000 will have some form of

hearing loss by the age of 17.

2.12

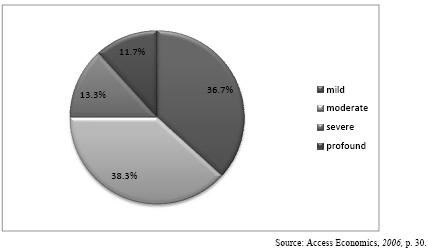

Access Economics reported that the estimated severity of hearing loss in

the Australian child population is currently 36.7 per cent mild, 38.3 per cent

moderate, 13.3 per cent severe and 11.7 per cent profound, as seen in Figure

2.2 below.[7]

Figure 2.2: Hearing loss in

Australian children by severity, 2005 (n=10,268)

2.13

The Hear and Say Centre noted in their submission that, according to the

World Health Organisation, hearing loss is the most common disability in new

born children worldwide.[8]

The Victorian Deaf Society submitted that more children are having their

hearing impairment diagnosed, but fewer children are being found to have a

severe-profound hearing loss. This is attributed to medical advances and more

sensitive testing.[9]

2.14

Many submitters noted that hearing impairment in Indigenous children is

particularly high. This issue is discussed in detail at chapter eight of this

report.

Prevalence of hearing impairment in

adults

2.15

Access Economics reported that amongst adults, the prevalence of hearing

loss varies over age groups. Table 2.2 is a summary of hearing loss among adults

by age.

Table 2.2: Hearing loss prevalence

by age group

|

Age group |

Hearing loss as a proportion of all people in each

age group. |

|

15 to 50 years |

5 % |

|

51 to 60 years |

29 % |

|

61 to 70 years |

58 % |

|

71 years and older |

74 % |

Source: Access Economics, Listen Hear! The economic

impact and cost of hearing loss in Australia, (February 2006), p. 5.

2.16

The committee heard that hearing loss was more prevalent in men than

women due to their higher exposure to workplace noise, though the gap reduces

as people get older.[10]

Sixty per cent of adults with a hearing loss are male, and approximately half

of these men are of working age (i.e. 15 to 64 years).[11]

The economic and social impacts of this are explored in chapters three and four

of this report.

2.17

Of the 3.55 million Australian adults with hearing loss, 66 per cent had

a mild loss, 23 per cent had a moderate loss and 11 per cent had a severe or

profound hearing loss.[12]

Prevalence projections

2.18

Access Economics estimated that the prevalence of hearing impairment in

children is likely to increase from 10,268 in 2005 to 11,031 by 2050, an

increase of 7.5 per cent. Unlike projections for the adult population, this

estimate is 'fairly static' and is based on population growth.[13]

2.19

Hearing loss prevalence in the adult population is expected to more than

double by 2050 to one in four. For all males in Australia, hearing loss is

projected to increase from 21 per cent in 2005 to 31.5 per cent (nearly one in

three) in 2015. The projected increase will be largely driven by the ageing

population. In the absence of a large scale prevention program, the severity of

hearing loss is not expected to change. The growth in hearing loss for males is

expected to increase from 21 per cent to 31.5 per cent and for females from 14

per cent to 22 per cent.[14]

Figure 2.2: Projected growth in

hearing loss by gender (worse ear)

2.20

New South Wales (NSW) Health commented that hearing loss projections

support the case for early detection and intervention programs, as well as

strategies to prevent noise induced hearing loss through hearing health

promotion and education.[15]

Causes of hearing loss

2.21

As discussed above, around one in six Australians suffer from some

degree of hearing impairment.[16]

Hearing loss can be either present at birth (congenital) or occur later in life

(acquired).[17]

2.22

There are three types of hearing loss: conductive, sensorineural or

mixed.[18]

The diagram of the parts of an ear provided below at figure 2.3 will assist to

understand aspects of hearing loss.

Figure 2.3: The hearing system

Source: Access Economics. Listen

Hear! The economic impact and cost of hearing loss in Australia, (February 2006),

p. 15.

2.23

Conductive hearing loss occurs as a result of blockage or damage to the

outer and/or middle ear, and can be either transient or permanent. The most

common cause of hearing loss in children is eustachian tube dysfunction, which

may affect up to 30 per cent of children during the winter months. This may

lead to fluid in the middle ear, or otitis media, in which a bacterial

or viral agent infects the middle ear or ear drum. Otitis media may result in

perforations of the ear drum, and may over the long term cause scarring of the

ear drum.[19]

2.24

Sensorineural loss is caused by damage to, or malfunction of, the

cochlea (sensory) or the auditory nerve (neural). Damage can arise from

excessive noise exposures, chemical damage such as smoking, environmental

agents or medications and from the ageing process. Hearing loss can also result

from damage to the auditory nerve. Sensorineural hearing loss is permanent by

nature.[20]

Hearing loss in children

2.25

Most children born with a hearing loss have a sensorineural hearing loss.[21]

The Alliance for Deaf Children noted that approximately 60 per cent of

congenital deafness is due to genetics, with the remaining 40 per cent due to

environmental factors or complications during pregnancy or birth. Approximately

95 per cent of children with hearing loss are born to parents with normal hearing.[22]

2.26

Aussie Deaf Kids reported that conductive hearing loss in children is

due mainly to:

- otitis media – a middle ear infection which is usually treatable

and temporary. Otitis media is particularly prevalent in Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander populations where the disease is likely to become chronic and

respond poorly to treatment, as discussed in more detail in chapter eight;

- cholesteatoma – a slow growing, non‐malignant

growth behind the ear drum which can result in serious damage to the middle and

inner ear. It is normally the result of severe and repeated middle ear

infections;

- microtia and aural atresia – a congenital deformity of the outer

ear and the absence of an ear canal. Microtia and aural atresia has a reported

incidence of approximately one in every 6,000 births worldwide. In most cases, microtia

is also associated with aural atresia or stenosis and these children will have

a conductive hearing loss.[23]

Ageing

2.27

As part of the ageing process there is a gradual loss of 'outer hair

cell' function in the cochlea or inner ear. This diminishes the ability to

distinguish similar speech sounds, or sounds heard simultaneously, such as

speech in a noisy setting.[24]

Therefore, as the committee heard many times during this inquiry, as the

Australian population ages there will be increasing numbers of people with

hearing loss.

Noise induced hearing loss (NIHL)

2.28

Noise induced hearing loss is associated with 37 per cent of all hearing

loss.[25]

Workplace noise and recreational noise are the most common source of noise

injury and, according to the Australian Society of Otolaryngology Head and Neck

Surgeons (ASOHNS), the most common form of preventable hearing loss in the

western world.[26]

The ASOHNS argued that it is a very important consideration in terms of

maintaining the community's hearing, as its impact is felt across all ages in

the community.

Occupational noise induced hearing

loss (ONIHL)

2.29

An estimated one million employees in Australia may be exposed to

dangerous levels of noise at work. Sound and pressure was the stated cause for

over 96 per cent of workers’ compensation claims for hearing loss in 2001-02.

Risk of hearing impairment in the workplace may also arise through exposure to

occupational ototoxins (these include solvents, fuels, metals, fertilisers,

herbicides and pharmaceuticals, as discussed further in chapter six). Damage is more likely if a person is exposed to a combination of

substances and noise.[27]

2.30

The Department of Health and Ageing (DOHA) submitted that the principle

characteristics of ONIHL are that:

- the hearing loss is usually on both sides as most noise exposures

are symmetric;

- symptoms may include gradual loss of hearing, hearing sensitivity

and tinnitus (the experience of noise or ringing in the ears where no external

physical noise is present);

- noise exposure alone does not usually produce a loss greater than

75dB at high frequencies and 40 dB at low frequencies, however hearing

impairment may be worse where age-related losses are superimposed; and

- the rate of hearing loss due to chronic noise exposure is

greatest during the first 10–15 years of exposure.[28]

2.31

Safe Work Australia provided evidence to the committee that each year

there are an average of 3,400 successful workers' compensation claims for ONIHL

in Australia. The nature of hearing loss is that it has a long latency, and

there is often difficulty determining whether a loss is work related. Therefore

Safe Work Australia believes that these figures are probably understated.[29]

2.32

Analysis of workers' compensation claims for hearing loss indicate that

three occupational groups (labourers and related workers; tradespersons and

related workers; and intermediate production and transport workers) account for

88 per cent of claims. The three highest industry sectors affected by

occupational hearing loss are the manufacturing, construction, transport and

storage industries. The highest incidence rates were in mining; construction;

and electricity, gas and water supply.[30]

2.33

Dr Fleur Champion de Crespigny of Safe Work Australia outlined for the

committee some of the highlights of the National Hazard Exposure Worker

Surveillance (NHEWS) Survey, 2008:

The main findings of the research are [that between] 28 and

32 per cent of Australian workers are likely to work in an environment where

they are exposed to non-trivial loud noise. Workers’ sex, age, night work,

industry and occupation all affected the likelihood of a worker reporting

exposure to loud noise. Of these, male workers, young workers and night workers

all had increased risk of exposure to loud noise. [Excluding the mining

industry], [m]anufacturing and construction workers had the greatest risk of

being exposed to loud noise...Technicians and trades workers, machinery operators

and drivers and labourers were the occupations with the greatest odds of

reporting exposure to loud noise.[31]

Farmers and hearing loss

2.34

The agricultural sector also reports high levels of hearing loss among

farmers. 65 per cent of Australian farmers have a measurable hearing loss,

compared to 22-27 per cent of the general population. Hearing loss is also high

among young farmers compared to the general population.[32]

A 2002 study found that of the farmers surveyed, the average hearing loss

commenced earlier and remained much greater than that expected for an

otologically normal population.[33]

2.35

The loss of hearing in the farming sector is due to noisy activities

such as using a chainsaw, operating noisy workshop equipment, operating firearms

or driving tractors which do not have a cabin over a sustained period. While

education programs have been conducted to improve hearing protection for farm

workers, the 2009 Rural Noise Injury Program assessment found that:

- only around one third of farmers reported adoption of higher order

noise reduction strategies, such as upgrading to quieter equipment and

dissipating workshop noise;

-

farmers aged 35-44 years had significantly worse hearing in their

left ears (the ear closest to the tractor engine when the farmer is turned

around watching behind him); and

- younger farmers who always used hearing protection had

significantly better hearing than those who did not.[34]

2.36

Data collected predominantly from the Rural Noise Injury Program

(1994–2008), which includes over 8,000 hearing assessments of mostly NSW farmers,

indicate that there has been an improvement in the hearing of farmers, with the

proportion of farmers with 'normal hearing' increasing over the period. For

younger farmers 15-24 years, those with normal hearing increased from 57.3 per

cent in 1994-2001 to 77.0 per cent for the 2002–2008 period.[35]

The difficulties of relying on

workers' compensation data to determine the prevalence of ONIHL

2.37

Most discussion of the prevalence of ONIHL in Australia relies on

workers' compensation data. However, there are a number of factors which may

indicate that workers' compensation data do not provide a reliable measure of

ONIHL.

2.38

For a worker to access compensation for ONIHL, the hearing loss must

reach a minimum threshold. The minimum threshold differs across jurisdictions,

but the Heads of Workers' Compensation Authorities recommended a threshold of

10 per cent hearing loss in 1997.[36]

Access Economics commented that a fall in workers' compensation claims arising

from ONIHL in recent years is most likely due to the introduction of minimum

thresholds. Dr Warwick Williams commented that thresholds in effect hide the

real incidence of hearing loss in the community.[37]

2.39

The Australian Safety and Compensation Council (ASCC) reported in 2006

on work-related hearing loss in Australia and stated that compensation

statistics do not fully reflect the true incidence and cost of industrial

deafness:

Whilst it is a positive sign, an improvement (reduction) in

the number of claims being made does not necessarily correlate with an

improvement in the prevention of NIHL. But they provide good indicators and

useful trends for further examination.[38]

2.40

Factors contributing to this understatement include:

- not all employees make claims, or are eligible to make claims,

due to differing criteria;

- there is a need to establish that the disease is work-related;

-

the industrial deafness threshold is not the same across all

jurisdictions;

- industries in which employees are known to be at high risk of ONIHL

are not all identified by the analysis of compensation claims (e.g. the music

entertainment industry);

- the analysis focuses on industries with the largest number of

claims. There may be smaller industries with not many claims, but a very high

rate of claims per employee;

-

employees move between jobs, so the resulting hearing condition

may be due to a combination of activities; and

- employees may feel under pressure not to claim (e.g. if they

think it may impact on their security of employment).[39]

2.41

In the agricultural sector the reasons for the underestimate include:

- only around 54 per cent of the estimated 375,000 strong

agricultural workforce are actually 'employees'. Most farms are small family owned

businesses with no employees;

-

'employees' within agriculture are a relatively young demographic.

Noise injury is often not apparent for a number of years and job movement of

young workers can be high so young workers are less likely to be able to

establish a claim; and

- hearing screening services in rural areas are often lacking, and

small family-owned farm businesses can not provide hearing screening services

themselves. This means baseline and periodic hearing assessment to establish

noise injury is difficult.[40]

2.42

While legislation in all Australian jurisdictions seeks to protect employees

from exposure to dangerous levels of noise, the evidence indicates that

problems remain in the implementation and acceptance of hearing protection.[41]

The findings of the NHEWS Survey, 2008 with regard to training and

provision of safety equipment in noisy workplaces, revealed some areas of

concern, as Dr Champion de Crespigny explained:

Training on how to prevent hearing damage appears to be

underprovided in Australian workplaces. Only 41 per cent of exposed workers

reported receiving any training in how to prevent hearing damage. There also

appears to be a reliance on the provision of personal protective equipment for

reducing exposure to loud noise. The provision of control measures in

workplaces was affected by industry, occupation and workplace size. But, with a

few exceptions, in general, industries and occupations with high odds of

exposure to loud noise also seemed to have high odds of providing control

measures...On the other hand, smaller workplaces—workplaces of a range of sizes

but with fewer than 200 workers—were less likely to provide comprehensive noise

control measures.[42]

2.43

Safe Work Australia told the committee about the Getting Heard

report, which has been funded by DOHA, and which is due to be launched during

Hearing Week in August 2010. Mr Wayne Creaser of Safe Work Australia explained

that the Getting Heard project:

...is intended to look at what impacts on the effective

prevention of hazardous occupational noise and what the attitudinal and

institutional barriers are to effective control measures being put in place.[43]

2.44

Access Economics reported that there is no nationally coordinated ONIHL

prevention campaign.[44]

This issue is examined in detail in chapter seven of this report.

2.45

ASOHNS argued the need for reform of noise regulations to implement an

evidence-based standard that can be shown to be effective in preventing or

minimising ONIHL. ASOHNS added that current regulations do not provide for

overarching guidance, supervision, education or the provision of information

for employees and employers. The ASOHNS recommended that government should

implement policy regarding occupational noise induced hearing loss that

provides:

- evidence-based guidance and education to employers and employees

with regard to ONIHL; and

- a nationally agreed benchmark method for assessing occupational

hearing loss.[45]

2.46

In relation to the comments by ASOHNS concerning research, the committee

notes that DOHA was unable to source data linking a reduction in the incidence

of work related noise induced hearing loss to prevention activities.[46]

Acoustic shock and acoustic trauma

2.47

Two further sources of preventable hearing loss, commonly associated

with the workplace, are acoustic shock and acoustic trauma.

2.48

Acoustic shock describes the physiological and psychological symptoms

that can be experienced following an unexpected burst of loud noise through a

telephone headset or handset, and which most often occurs in call centres.[47]

2.49

Acoustic trauma refers to the physiological and psychological symptoms

that can be experienced following exposure to very loud noises for a short

period of time such as a bomb explosion, localised alarm systems, or artillery

fire. Some incidents of both acoustic shock and acoustic trauma may result in

temporary hearing loss, however research is not currently available to

determine the contribution to permanent hearing loss.[48]

2.50

Of further interest for research into the long-term effects of acoustic

shock is the occurrence of tinnitus and a possible relationship with the onset

of Meniere's disease.[49]

Recreational hearing loss (RHL)

2.51

Hearing loss due to recreational activities was seen as a real and

increasing issue. Concerns were voiced about the lack of regulatory controls on

noise exposures for audiences at music and vehicle racing events, patrons in

restaurants and bars and for the use of personal music players. Witnesses also

commented on increased use of personal music players such as iPods. Personal

music players are a growing source of concern for hearing health, with Apple

indicating that there are 28 million iPods in use worldwide.[50]

2.52

Self Help for Hard of Hearing people Australia (SHHH) argued that

recreational hearing damage is now at 'epidemic' levels through the use of personal

music players and commented 'We don't appreciate it yet, but researchers know

that young people are losing their hearing at a rate never before experienced'.[51]

Mr Daniel Lalor went further, stating that personal music players 'will be the

cigarettes and asbestos of Generation Y'.[52]

2.53

The University of Melbourne Audiology and Speech Sciences commented:

It is clear that recreational noise exposure reaches levels

that are known to be dangerous. It is not well-established how much this recreational

exposure is contributing to significant hearing loss in later life and the

burden of disease and economic costs. Other recreational activities such as

shooting, motor sport and the use of power tools may also be contributing to

the levels of hearing loss in the community.[53]

2.54

There were differing views concerning recreational exposure to noise on

hearing loss. Access Economics stated that there is no epidemiological data

that systematically examines RHL. While studies have shown short term or minor hearing

damage resulting from personal music players and music exposure generally,

there are no studies available that document exposure outcomes that result in

permanent measurable and significant hearing loss. Access Economics went on to

state that researchers have not reached consensus on the contribution of RHL

makes to the overall prevalence of hearing loss.[54]

2.55

Dr Warwick Williams has found that recreational noise can be loud enough

to cause damage if the length of noise exposure is long enough. Dr Williams

argued that dangerous recreational noise exposure occurs at a particular stage

of life (i.e. among young people), and there is no evidence that people are

exposed for long enough periods to do damage.[55]

2.56

The Deaf Society of Victoria commented that past research had not been

able to draw a conclusive link between personal music players and hearing loss,

but noted a recent (2009) study which suggested there was a link.[56]

The Society also commented that, in its experience, more adolescents and young

people are exhibiting signs of hearing damage:

...already increasing numbers of adolescents and young adults

are showing symptoms related to the early stages of noise-related deafness,

such as distortion, tinnitus, hyperacusis, and threshold shifts...This

development has also been evidenced in recent hearing screenings undertaken by

Vicdeaf.[57]

2.57

Other witnesses provided similar evidence arising from their direct

contact with young people. Mr John Gimpel of the Hearing Industry Association

commented that the experience of people undertaking hearing testing indicated

that:

...the prevalence of high-end loss in people in their late 20s

is really starting to come through, and these people have had absolutely no

exposure to any noise in the workplace—all they have ever had is the doof-doof

in their ears.[58]

2.58

Mrs Noeleen Bieske of the Deafness Foundation commented:

The seal of the iPod is so tight in the ear that it is just

giving that full blast going into the hearing mechanism. These young people are

not aware. I take calls from people saying, 'I've got this shocking ringing in

my ears.' When I say, 'What have you been doing?' they say, 'I’ve been wearing

my iPod for a minimum of three to four hours a day, I play in a band, I don't

wear musician plugs and I also work in a bar in a pub.' These kids are 30 maybe

or in their late 20s and they are saying, 'Now I can't hear properly. What am I

going to do?'.[59]

2.59

Other witnesses pointed to developments overseas. In 2008, the European

Union Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks on

Personal Music Players and Hearing published a report which warned that

listening to personal music players at a high volume over a sustained period

can lead to permanent hearing damage. It was reported that five to 10 per cent

of listeners risk permanent hearing loss. These are people typically listening

to music for over one hour a day at high volume control settings. It estimated

that up to 10 million people in the European Union may be at risk.

2.60

In September 2009, the European Commission sought to establish new

technical safety standards that would set default settings of players at a safe

level and allow consumers to override these only after receiving clear warnings

so they know the risks they are taking. Dr Burgess indicated that the Product

Safety Section of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) has

been alerted to these developments, and that they have established a project to

look at these issues.[60]

2.61

In France the noise level of personal music

players has been limited to 95dB.[61]

In Switzerland, limits on audience exposure at venues with amplified music have

been set with a 93 dB(A) limit for events for under 16 year olds and a 100

dB(A) limit for other events plus a requirement to inform and supply free

hearing protectors when over 93 dB(A).[62]

Causes and prevalence of

deafblindness

2.62

The committee heard evidence about the particular challenges faced by

Australians who are deaf and blind (deafblind). The Australian DeafBlind

Council stated that there are some 300,000 people in Australia who are

deafblind (if people with a mild hearing loss are included). Of these 7,000 to

9,000 are under 65 and 281,000 (or 93.7 per cent) are 65 years of age and over.[63]

The Senses Foundation provided evidence that in Western Australia (WA) 63 per

cent of deafblind people were male.

2.63

The causes of congenital deafblindness include infections such as

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Congenital Rubella Syndrome (CRS), chromosomal

abnormalities, genetic disorders and premature birth.

2.64

Senses Foundation indicated that the incidence of deafblindness arising

from CRS is relatively rare due to the introduction of widespread vaccination

against rubella. In Australia there were no reported cases of CRS between 1997

and 2002. However, Senses noted that concerns have been expressed about the

maintenance of the level of immunisation required to stop the spread of

rubella. In particular, the lower immunisation levels in Indigenous communities

may not provide adequate immunity.[64]

2.65

There are a number of chromosomal conditions and syndromes which may

lead to deafblindness. The incidence of two, Usher's syndrome and CHARGE

syndrome, have increased in recent years. Usher's syndrome is the most common

disease associated with hearing loss and eye disorders.

2.66

Deafblindness is also associated with prematurity and Foetal Alcohol

Spectrum Disorder (FASD). The evidence indicates that there appears to be a

strong relationship between poverty and the incidence of FASD.

2.67

Acquired deafblindness may be from illnesses such as meningitis,

encephalitis and brain tumours, and trauma such as head injures and ageing.

2.68

The Australian DeafBlind Council stated that there is a lack of

'appropriately qualified interpreters' to assist deafblind people to access

health services and community support, and that this causes distress for those

most affected.[65]

Committee comment

2.69

The evidence provided to the committee clearly indicates that hearing

impairment is a major issue in Australia, with one in six Australians suffering

from some degree of hearing loss. While much of the expected increase in

hearing impairment over the coming decades is due to the ageing of the

population, a significant proportion of hearing loss is due to noise damage

which is preventable.

2.70

Governments have recognised the dangers that workplaces can pose to

hearing, and have legislated to enforce safety measures, and implemented

prevention strategies. However, analysis of workers' compensation data indicate

that working in many industry sectors still poses a risk to hearing health.

Evidence was received that the workers' compensation data may not be revealing

the full extent of ONIHL.

2.71

Evidence also indicates that recreational activities may be an

increasing cause of hearing impairment. Whilst the scientific proof is still

ambiguous, the committee believes that there may be some connection between

hearing loss and the extensive use of personal music players. The committee

notes the evidence of hearing services which have observed emerging patterns of

the detrimental impacts of recreational noise among young people.

2.72

The committee also notes that overseas there have been moves to limit

noise levels on personal music players as well as limiting audience exposure at

music venues. The committee considers that the problem of recreational hearing

loss should be targeted in two ways: awareness campaigns directed a young

people (see chapter seven for recommendations); and introducing limits to

exposure to recreational noise.

2.73

The committee heard that the ACCC is already investigating the future

application of noise limitations for personal music players sold in Australia.

2.74

Whilst their support needs are often acute, the particular issues facing

deafblind people in Australia broadly reflect the issues facing all people with

a hearing impairment, namely: access to services and support; forecast

increased prevalance; and the need for greater understanding about causes of

deafblindness. The committee offers its encouragement to the Australian

Deafblind Council in their efforts to represent and advocate for deafblind

people. The committee has made recommendations at chapters five and six which,

if implemented, will benefit deafblind people.

Recommendation 1

2.75

The committee recommends that the Department of Health and Ageing

work with the appropriate agencies and authorities to devise recreational noise

safety regulations for entertainment venues. Specifically, where music is expected

to be louder than a recommended safe level, that the venues be required to:

(a) post prominent

notices warning patrons that the noise level at that venue may be loud enough

to cause hearing damage; and

(b) make ear plugs freely

available to all patrons.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page