Chapter 2

The Australian healthcare system – expenditure, access and outcomes

Introduction

2.1

The government has stated that it remains committed to its election

promise of not making cuts to the health budget. However, the National Commission

of Audit (the commission) is looking for areas of waste and inefficiency. The

government has indicated that if any savings are identified by the commission,

these funds would be reallocated to other priority areas in the same portfolio.[1]

2.2

This chapter will examine government healthcare expenditure and suggested

areas where efficiencies may be found. It will also consider the importance of

primary and preventative healthcare, the specific proposal to charge a $6

Medicare co-payment and other related areas raised with the committee.

Government expenditure on health

2.3

Healthcare has been highlighted as an area of growing government

expenditure, with the system under pressure from a growing and ageing

population with high expectations around their level of healthcare.[2]

However, the committee notes that Australia's health expenditure is moderate

when compared to international benchmarks (see figure below).[3]

2.4

Total health expenditure in Australia has increased substantially over

the last decade from $82.9 billion in 2001-02 to $140.2 billion in 2011-12 in

real terms.[4]

However, it should be noted that as a proportion of GDP this represents an

increase of just 1.2 per cent, which suggests that health spending

has been reasonably stable over time.[5]

2.5

Despite this, the committee acknowledges that recent Intergenerational

Reports have suggested rising healthcare costs will put increasing pressure

on the health budget in coming decades.[6]

This will be compounded by an ageing population, the cost of new technologies

and pharmaceuticals, the introduction of programs such as the National

Disability Insurance Scheme, and the growing burden of chronic disease.[7]

Effectiveness

2.6

The committee notes Australia's healthcare system is reasonably

efficient when compared to international benchmarks.[8]

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development's (OECD) Health

at a Glance 2013 indicates that Australia's health system achieves

excellent outcomes at an efficient price:

Australians also enjoy good access to a high quality health

care system. It consistently rates among the top five countries in terms of

survival after being diagnosed with cancer or after suffering acute myocardial

infarction (heart attack). These good outcomes are achieved at a reasonable

price, with Australians spending 8.9% of their GDP on health compared to an

OECD average of 9.3%.[9]

2.7

Dr John Daley, CEO of the Grattan Institute, who appeared before the

committee in a private capacity, commented that the efficiency of the

Australian system meant that finding substantial savings in health expenditure would

be challenging:

The issue with health is that Australia has one of the most

efficient health systems in the world. We looked at this in the supplementary

materials to [the Grattan Institute] Game changers report. That showed

that Australia has some of the best health outcomes in the world, if you

measure them by mortality, but you can use lots of other measures as well. And

we have what you might describe as middle-of-the-road spending. So, in terms of

outcome for the amount we spend, we do it about as well as anyone else in the

world and indeed better than most people.[10]

2.8

Ms Alison Verhoeven, Chief Executive Officer of the Australian Health

and Hospitals Association (AHHA), noted that Medicare was the foundation of the

Australian healthcare system, and that its provision of universal access to

good treatment was one of the reasons why health indicators are predominantly

good, while costs are reasonable.[11]

2.9

Mr Ian McAuley, Adjunct Lecturer, University of Canberra, noted that most

successful health systems were built around a single national insurer, such as

Medicare, that kept costs low:

The huge cost is the incapacity of a fragmented private

insurance system to control the costs imposed by service providers. That is

why, for instance, the USA stands out there with health expenditure of 18 per

cent of GDP—a huge burden on that country—whereas most developed democracies

were around nine per cent of GDP. The countries which have been most successful

are those which have used a single national insurer to keep costs under

control.[12]

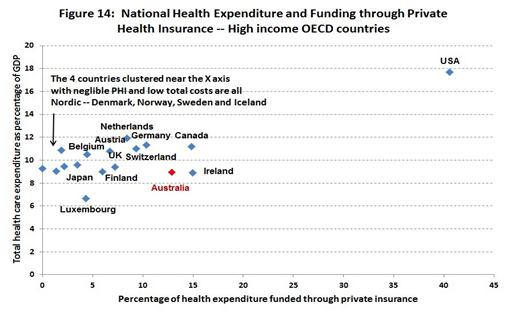

2.10

The figure below shows that countries that rely more heavily on private

insurance to fund healthcare have more expensive health systems.[13]

The importance of expenditure on primary care and preventative health

measures

2.11

To address the burden of complex conditions and chronic disease in the

future, the committee heard of the importance of primary care and preventative

health measures. An increased focus on and investment in primary care and

preventative health campaigns has the potential to alleviate the burden of

health costs over time as people would stay healthier for longer and manage

complex or chronic conditions with the assistance of their General Practitioner

(GP) rather than enter expensive hospital care. Ms Verhoeven summarised this

view:

We know that preventive health is critical in the long term

to getting good health outcomes, but we also know that there are not short-term

wins from investment in preventive health. So, if you want an investment win

from a dollar spent last year or the year before, you are not going to see it.

The reality is that those wins will not be seen for 20, 30 or 40 years.[14]

2.12

Ms Jennifer Doggett, Fellow, Centre for Policy Development, also emphasised

that the dividends of public health campaigns only become apparent over time:

There is a lot of data which

shows that, in a number of areas, it is a sensible investment: investment in

preventative care in particular strategies will deliver significant gains down

the track. That does not necessarily mean every health promotion campaign or

every preventative strategy; it means evidence based preventative health

care....Certainly you would have to look at the fact that Australia is a global

leader in reducing smoking; you would have to look at government's investment

in, say, the 1970s and 1980s in anti-smoking campaigns paying dividends now in

the reduction of smoking-related illnesses that we are seeing

turning up in our hospitals.[15]

2.13

The submissions made to the committee by the Grattan Institute and the

Public Health Association of Australia also highlighted how some preventative

health strategies, such as raising excises on tobacco and alcohol, could help

reduce health costs in the long run while also lifting government revenues.[16]

2.14

Investment in prevention measures was also supported by Mr Chris Twomey,

Director of Social Policy, West Australian Council of Social Service, as a way

to reduce costs in certain areas:

Any analysis of the health budget shows the areas we have

been blowing out have been hospitals, crisis care, PBS and so forth, and what

we actually want to do to reduce the blow-out in those costs is more primary

care and more prevention and early intervention. We want to get people to see

their GPs more, not less.[17]

2.15

Professor Michael Daube, Professor of Health Policy, Curtin University

and Director, Public Health Advocacy Institute of Western Australia, was

concerned that funding for preventative health services is not seen as a 'soft

target' for cuts to the health budget. Professor Daube highlighted the

substantial reductions in preventable death and disease, and the reduced costs

to the community and health system from the modest funding for prevention

measures in areas including immunisation, tobacco, road safety and HIV-AIDS. [18]

2.16

Professor Geoffrey Dobb, Vice-President, Australian Medical Association,

(AMA) stressed that preventative health should be a major part of making

healthcare funding sustainable:

The effects will not be short term, but if we are to achieve

sustainability in health care funding in the budget in 10 or 15 years time,

then we need to be doing those things right now. On the other side, in terms of

managing chronic disease that is already here, yes, general practice is the key

to that, and it is key to keeping people out of hospital and improving the

quality of their lives. General practitioners are increasingly becoming experts

in the management of chronic and complex disease in the community. The costs of

caring for people in the community are far less. What we need to do is support

the general practice model to provide those services where they are delivered

in a way that is better for patients, more appropriate for the health care system

and, ultimately, will bring a smile to the faces of treasurers.[19]

Suggestions to fund preventative

health measures

2.17

Professor Daube noted that the taxation of harmful products such as

tobacco and alcohol brings in around $14 billion a year and some of this could

be used for prevention measures. Professor Daube also noted that the

introduction of a volumetric tax for alcohol could bring another estimated half

a billion dollars a year which could be used to fund preventative health

services.[20]

Committee view

2.18

The committee notes the long-term success of preventative health

measures including tobacco control and sun protection/skin cancer prevention

and believes that there should be a greater focus on evidence based preventative

health programs to reduce acute healthcare costs in the future.

Recommendation 1

2.19

The committee recommends that the government use funding found through

efficiencies to increase evidence based preventative health measures aimed at

reducing the burden of chronic conditions in the future.

Potential efficiencies in Australian health expenditure

2.20

The committee received evidence that areas of the Australian health

system could be more efficient, and these are discussed below.

Duplication across agencies and levels

of government

2.21

One area put forward for increased efficiency was the duplication of

services across Commonwealth and state health agencies. Mr Frank Quinlan, Chief

Executive Officer, Mental Health Council of Australia, stated that in relation

to mental health programs:

What we see in the interactions between state and territory

governments and the Commonwealth government currently is a considerable overlap

in programs and a considerable gap in programs, so we see some Commonwealth

programs taking on similar roles to some state programs. We have traditionally

seen state governments providing direct services, hospital based services and

supporting community mental health services for instance. We have seen the

Commonwealth as a relatively recent entrant into the mental health domain

having provided funding to a range of programs. What we principally mean by

that statement is not so much that one government or the other ought to abandon

the space but that we ought to find ways for state and federal governments to work

together to ensure that we are less burdened by overlaps and less burdened by

gaps between the programs. It is about building a cooperative relationship

between the states and the Commonwealth.[21]

2.22

Ms Verhoeven questioned the recent increase in bureaucratic

infrastructure:

So one does have to query why there has been so much

bureaucratic infrastructure set up to handle something which six or seven years

ago was done by one or two agencies. I do think there is some scope for

rationalisation there. Just looking at the infrastructure needed to support

each of these individual agencies—and I talk about IT services, human resource

services, communications services and website building services—it is really

very complex and it is not money well spent.[22]

The duplication of services - private

and public health providers

2.23

The committee heard evidence there is duplication of funding and

services between public and private providers, as there is not a clear

distinction between the different roles they play and the services they

provide. Ms Verhoeven told the committee:

There are clearly issues with a system that sees private

hospitals contracted to treat public patients while public hospitals compete

for private patients. Like all industries and systems there are opportunities

to improve efficiencies and value in the system. There is significant variation

in the costs of health service delivery across the country, some of which is

explained by complexity in the patient mix, by geography and by market forces,

but there are also avoidable aspects to these cost variations.[23]

2.24

Dr Anne-marie Boxall, Director, Deeble Institute for Health Policy

Research, AHHA, spoke about duplication between public and private health

insurance providers:

The problems with Australia's health insurance arrangements

go back to the origins of Medicare and Medibank, where we had an existing

private health insurance system that had tax subsidies and then we created a

universal healthcare system. The problem has always been that we have had two

competing systems, but the private health insurance does not necessarily add

function as a top-up, an optional extra. In some ways it duplicates what

Medicare does and in other ways it is a top-up. So the structure of the system

is problematic compared with most other countries.[24]

Private health insurance rebates

2.25

The last Intergenerational Report, Australia to 2050: future

challenges, stated that private health insurance rebates were a substantial

and growing component of government health expenditure, predicted to increase 'by

9 per cent a year over the 10 years from 2012-13, adding a cumulative $33

billion to spending'.[25]

2.26

These rebates were not only seen as an inefficient and costly tax

expense for the Commonwealth, but it was also suggested that they had not

achieved their intended purposes. The Grattan Institute submission included a

report that identified the health insurance rebate as a potential expenditure

saving for government in the Australian health budget:

Removing the private health insurance rebate could save $3.5

billion in expenditure. Savings of $5.5 billion from the cost of the rebate

would be offset by an increase in demand for public hospital services.[26]

2.27

Dr Stephen Duckett, Program Director for Health for the Grattan

Institute, appearing in a private capacity, also commented that the private

health rebate was not effective in reducing demand on public hospital services:

The argument for the private health insurance rebate when it

was first introduced was that it would reduce demand on public hospitals. My

reading of the evidence is that there was not a great impact on public hospital

utilisation with the introduction of the rebate.[27]

2.28

Mr Peter Davidson, Senior Adviser, Australian Council of Social Service

(ACOSS), suggested that the private health insurance rebate for ancillaries[28]

was not achieving its intended results:

The 30 per cent to 50 per cent private health insurance

rebate for ancillaries cover, we believe, should go. The main justification for

that rebate was to reduce public expenditure on hospitals. There is not a

direct link between ancillary benefits and those expenditures. Indeed, we have

inequity where people who can afford private health cover are being subsidised

substantially for private dental care while people on poverty-level incomes are

waiting a year on year or more for a lower quality public dental care.[29]

Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS)

and Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS)

2.29

The committee heard evidence that supported full-scale reviews of the MBS

and PBS, as well as expediting the ongoing review of MBS item numbers. Ms Verhoeven

stated:

Both the MBS and the PBS programs would benefit, in our

minds, from a review to determine opportunities for disinvestment of, for

example, redundant treatments and technologies, particularly at a time where

there is an increasing demand to add new treatments and technologies to these

schedules. We argue that regular scheduled review of MBS and PBS items would

ensure that the schedules remain current and appropriate in terms both of their

content and the rebate levels.[30]

2.30

Dr Duckett agreed the MBS could be reviewed, though advised that any changes

be undertaken with caution so disadvantaged individuals are not negatively

affected financially or in relation to access:

There are obviously parts of the [MBS] that have not been

revised and reviewed for decades, so you end up with certain items being over-renumerated

relative to others.[31]

2.31

The AHHA also recommended that the ongoing review of MBS item numbers by

the Department of Health be expedited and its recommendations prioritised by

government.[32]

Dr Boxall told the committee:

[The Department of Health's review of the MBS have] started

their work and they do have a very rigorous process set up through the...Medical

Services Advisory Committee. It does involve stakeholder consultation and the

reports are produced publicly. The problem with the process is that they have

done about 23 and there are more than 5,000 items on the MBS, so it is really

the scale of the project rather than the nature of it in itself.[33]

2.32

The Grattan Institute's submission noted potential Commonwealth savings

of $2 billion from PBS expenditure.[34]

This drew on evidence in a previous Grattan report by Dr Duckett that argued

three reforms to Commonwealth pharmaceutical subsidies were necessary:

The first is to establish a truly independent expert board.

Like New Zealand's Pharmaceutical Management Agency, it would manage

pharmaceutical pricing within a defined budget.

The second and vital change is to pay far less for generic

drugs, which can be bought for low prices because they are off-patent. In Australia

drug companies must cut prices by 16 per cent when a patent expires. Many countries

require much bigger cuts....

Down the line, a third reform should encourage people to use cheaper

but similar pharmaceuticals, which could save at least $550 million a year

more.[35]

2.33

Mr Davidson also commented that PBS subsidies should be reduced for

medicines that are off-patent to reduce costs for government and to deliver

more effective treatment to individuals.[36]

Committee view

2.34

The committee considers that more resources should be provided to

progress the ongoing review of MBS item numbers currently being undertaken by

the Medical Services Advisory Committee. This review is looking at all MBS

items to assess clinical need, appropriateness, and the currency of treatments

to improve both health outcomes for individuals and the financial

sustainability of the MBS more generally.

Recommendation 2

2.35

The committee recommends that the government commit to provide

additional resources to progress the review of Medicare Benefits Schedule item

numbers being undertaken by the Medical Services Advisory Committee.

Examining the proposal for a Medicare co-payment

2.36

Although the commission's findings have not been made public, there has

been some indication that the government is considering the introduction of a co-payment

for accessing GP services.[37]

2.37

The committee heard evidence from Mr Terry Barnes, Principal, Cormorant

Policy Advice, about a submission he drafted for the Australian Centre for

Health Research (ACHR) to the commission. The ACHR submission advocated introducing

a $6 co-payment on bulk-billed GP and emergency department visits. It estimated

that this would reduce Commonwealth health expenditure by $750 million over the

forward estimates from 2014-15 to 2017-18.[38]

2.38

The ACHR submission argued that a $6 co-payment would send affordable –

'less than the price of two cups of coffee' – and 'clear price signals to

Australians that their basic health care services are not free goods'.[39]

This would lead to consumers thinking twice before going to a GP with a minor

complaint, thus reducing the chance of over-servicing by GPs.

2.39

Mr Simon Cowan, Research Fellow and Target 30 Program Director from the Centre

for Independent Studies, supported the introduction of GPco-payments

generally, but suggested an additional reduction in the Medicare benefit paid:

...Our model involves not just a $5 co-payment but a $5

reduction in the Medicare benefit that is paid, and that is where the savings

to government will come from.

Applying that to GP visits, specialists, pathology tests,

diagnostic tests and optometry—which is a total of something like 292 million

services—the $5 payment will generate about $1.45 billion in savings. That

does not take into account any potential reduction in use as a result of

changing behaviours fromco-payments. That is simply taking the number of

services that are currently provided and applying a $5 co-payment together with

a $5 reduction in [services funded by the Commonwealth]...[40]

2.40

Both Mr Barnes and Mr Cowan contended that people would not start

attending emergency departments instead of GPs, in an effort to sidestep a

modest co-payment. Mr Barnes stated that emergency departments should also

implement a co-payment for unnecessary visits.[41]

Mr Cowan told the committee:

I think that the majority of people will continue to consume

health as they have before. As a result of the co-payment they will not go

instead to an emergency department because there are a variety of other costs

associated with going to an emergency department.[42]

2.41

Mr Barnes also suggested:

Provided it has a reasonable ceiling to protect the less

well-off, chronically ill and families with young children, there is no reason

why a co-payment on bulk-billed services should stop people going to the GP

when they need to.[43]

2.42

Mr Barnes told the committee that it was difficult to prove

over-servicing was endemic in the Australian system as this data is not

collected. However, he suggested that anecdotal evidence suggested there may be

a problem:

...what Medicare records is simply quantitative information. If

you go to the GP and claim a benefit for a visit, a visit is recorded. We do

not, as we do with acute care in hospitals, code what the person presents for.

So we do not really have as good a fix on how GP services are used. But,

anecdotally, particularly in areas where there are high concentrations of

doctors or of health services, there is at least anecdotal evidence that

services are overused.[44]

2.43

The committee notes there is research suggesting that the assumptions in

the ACHR submission are flawed.[45]

In addition, those opposed to the co-payment argued that 'anecdotal' evidence

is not sufficient to model the effects of a co-payment. Moreover, witnesses

suggested there is actually no problem with over-servicing in the health system

at the moment.[46]

The case againstco-payments

2.44

The committee heard evidence that a co-payment would not reduce health

expenditure substantially, and that it would negatively affect access to

quality and timely healthcare for some Australians, especially those on

low-incomes.

Reducing access for low-income

earners

2.45

Ms Jackie Brady, Acting Executive Director, Catholic Social Services

Australia, told the committee:

On the issue of co-payment...I

would hope to impress that given the low incomes that many of the people at the

lower end of the spectrum are surviving on—and I do describe it as surviving

because it is a week-to-week existence—and even though it is sometimes hard for

some of us to believe that a $6 co-payment is going to be enough to dissuade

somebody from going to the GP, that is in fact a reality.[47]

2.46

Professor Laurie Brown, Research Convenor, National Centre for Social

and Economic Modelling, University of Canberra (NATSEM), also saw the burden of

a co-payment falling disproportionately on low-income groups:

I think it will be absolutely clear that the distributional

impacts will fall onto socioeconomically disadvantaged families, and then there

is an additional question of what the administrative costs of implementing that

type of policy are.[48]

2.47

Dr Boxall advised that there was evidence showing that increases to co-payments had had this effect in other areas of healthcare:

There is also some evidence

looking at increasingco-payments for pharmaceuticals, and it was a substantial

increase. When they did it in 2005, they found that the volume of scripts

filled for essential medications—so not things like coughs and colds but things

like epilepsy drugs—dramatically reduced, including for concession card

holders. I do not think that in the space of a couple of months you can see

that people have been cured of epilepsy, soco-payments are having a

substantial effect on people and their access to health services.[49]

2.48

The committee heard that out-of-pocket healthcare costs in Australia

have risen at much faster rates than most other countries, which has already

placed a cost-barrier in the path of low-income groups. For instance, Dr Boxall

said:

There was a survey done by the Australian Bureau of

Statistics in 2009 where they found that one in 10 people reported that they

either delayed or sacrificed treatment by a specialist because of the cost, and

one in 11 did not fill a script because of the cost[50]

2.49

Ms Rebecca Vassarotti, Director of Policy, Consumers Health Forum (CHF) Australia,

also sawco-payments affecting those least able to afford it. Additionally, she

highlighted the other costs of accessing health services including, transport,

parking and possibly accommodation.[51]

Deferred GP consultations will

increase health problems in the future

2.50

Evidence considered by the committee suggested thatco-payments would

lead to many people deferring seeing a GP for minor ailments that had the

potential to become major conditions if left unchecked. Ms Vassarotti suggested

that this was already happening, due to existing cost barriers in healthcare:

I think often the response that consumers give us is that

they will delay care, meaning they will probably end up in emergency when they

are much sicker, and it will be much more expensive to treat their illness. So

from our perspective the introduction ofco-payments, particularly in areas

such as primary health, seem on the evidence of it very counterintuitive in

terms of resulting in a decrease in spend.[52]

2.51

Dr Duckett agreed:

...the RAND study [done in the USA between 1972 and 1982] found

that the reduction in use occurred in both what doctors judged as necessary

care and what doctors judged as unnecessary care. Patients are not themselves

very good people to choose, when they have got something wrong with them,

whether it is necessary or not, so by reducing what doctors think is necessary

care there is the potential to increase costs for the health system in the

longer term and also people suffer illness worse.[53]

2.52

Professor Dobb from the AMA noted their concerns about a lack of detail and

certainty around the co-payment proposal as well as that:

...a significant across-the-board increase in people's

out-of-pocket expenditure may act as a deterrent for people who need to see a

medical practitioner, allowing their disease to get worse to the detriment of

themselves and, ultimately, of the healthcare system if they present later with

more serious and complex disease that requires hospitalisation and a much more

costly course of treatment.[54]

2.53

Professor Dobb also queried the evidence base for the co-payment and

particularly the assumption that it would save the government money:

The AMA has done some modelling, based on the best

information available, about how such a measure might look. That was done by

Access Economics. It suggests that it will be at best cost-neutral and might

actually end up costing governments collectively—if you include state

governments, which look after the hospital system—more taxpayer dollars. At the

end of the day there is only one kind of government dollar, and it comes out of

the pockets of taxpayers.[55]

Cost-shifting to hospitals

2.54

The committee heard that some people who would be deterred from visiting

a GP by the introduction of a co-payment may instead seek treatment at

emergency departments in hospitals. This would lead to increased costs for

government in hospital expenditure. Ms Vassarotti told the committee:

Also there are issues such as co-payment being put in part of

the system. Potentially they recognise the differentiating value of those

services. So you get these potential perverse incentives where you might be

putting a co-payment on a GP service in primary health care but no co-payment

in an emergency room. So you are actually being forced into accessing services

that are more costly and less effective because of the way thatco-payments

have been implemented, particularly because of that ad hoc manner.[56]

2.55

Dr Duckett agreed thatco-payments could lead to cost shifting behaviour

instead of cost savings:

The other point I would make is that the estimates of savings

are highly sensitive to what people might do. For example, if only one in four

or one in five people who might otherwise have gone to a doctor decides to go

to a hospital emergency department then there are no savings for the

Commonwealth government at all and substantial increased costs for state

governments through increased costs on the public hospital system.[57]

2.56

Moreover, the South Australian Health Department estimated that a

$6 co-payment for a GP visit would actually cost the Commonwealth and

state governments almost $2 billion, because at least four per cent of people would

bypass a GP and attended emergency departments for minor ailments instead.[58]

Adding to regulatory burden

2.57

Evidence received by the committee also pointed to the potential for GPco-payments

to increase red tape for GPs and lift Commonwealth administration costs.

2.58

Professor Brown, NATSEM noted the administrative burden of charging a

$6 co-payment:

What I do not know is how you implement that type of system

of adding a $6 fee and what are the administrative costs of implementing that. I

think that is another element.[59]

2.59

Ms Verhoeven agreed:

More broadly, I think our concern aroundco-payments is that

there are administrative costs in collecting them. We do not think that it is

actually going to drive big returns back into the system anyway and that there

are probably better and smarter ways to save money.[60]

2.60

A recent report by Ms Doggett for the Consumer Health Forum also raised this

issue:

In fact, shifting expenditure to consumers can actually

increase overall costs if it requires a more complex system to administer or

results in a less efficient allocation of resources. For example, the

introduction of a $5 co-payment for bulk billed GP services would require

significant additional administration for general practices resulting in higher

transaction costs compared to the administratively simple process of

bulkbilling.[61]

Committee view

2.61

The committee acknowledges that the most important weapon in good preventative

health strategies is effective primary care delivered by GPs. A GP can identify

emerging conditions early before they require hospital or specialist treatment.

They can also assist people to manage complex, multiple and chronic ongoing

conditions more effectively. The role that GPs play in the health system leads

to better health outcomes for individuals and families. Moreover, it also leads

to more efficient health expenditure for government. Early intervention can arrest

or alleviate some of the complex and chronic diseases that see people end up in

our hospitals which is the most expensive place for people to be treated.

2.62

The committee believes measures which place a barrier to a person seeing

a GP are not in the best interests of keeping people healthy. Moreover, that

the proposal for a co-payment for GP and emergency department visits may cause

people to delay treatment and they would be more likely to need more expensive

hospital care.

2.63

The committee sees this co-payment as a blunt instrument that has the

potential to hurt the most vulnerable in our society, both financially in the

short-term and by risking their future health.

Recommendation 3

2.64

The committee strongly recommends that the government does not implementco-payments for GP consultations and emergency department services.

Other issues raised with the committee

Data collection

2.65

The committee heard that health data collection and sharing across

levels of government and between government departments should be improved, to

support the development good health policy that would achieve efficiencies for

government health expenditure in the long term.

2.66

Ms Verhoeven noted duplication of data collection across governments and

departments:

There are any number of agencies collecting data in some

shape or form from the states and territories and, by extension, from the

hospitals themselves. That is delivered to the Commonwealth. It is handled in

multiple agencies. Sometimes one agency collects the data from another agency

but then has to be signed off by the state and territory provider. The

mechanisms are cumbersome. We are in a position where we have a number of new

agencies now all responsible for data reporting, yet most of them are relying

on the services of the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare in any case

for original data sources.[62]

2.67

Dr Duckett's submission to the commission advocated that Department of

Health data be made more widely available for policy evaluation and research

purposes.[63]

2.68

Mr Barnes proposed that more data on the activity of GPs needed to be

collected:

...more work needs to be done to understand qualitatively the

activity profile of general practice. As I said, in terms of hospital

admissions, with the national morbidity database and now with activity based

pricing, we effectively code why people are admitted and what they are treated

for. We do not do that at the general practice level. I think we need to do the

qualitative work to make sure that this measure or any other demand management

measure is on the right track.[64]

2.69

The National Rural Health Alliance suggested that the government should

aim to improve available data on health outcomes and services in regional and

rural areas:

The capacity of [the

Australian Bureau of Statistics, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

and the COAG Reform Council] to deliver the data required for evidence-based

health funding, policy and programs is an important component of the ability of

the public service to provide good and timely advice to government.[65]

Committee view

2.70

Reliable data is essential for developing evidence based health policies

designed to improve health outcomes and increase efficiency in government

spending. The committee believes the collection and sharing of health data

could be greatly improved across levels of government and between government

departments. Consolidating the data held by agencies dealing with health and

care could reduce duplication and bureaucracy, thereby reducing government

expenditure.

Recommendation 4

2.71

The committee recommends that the government review health data

collected with a view to: consolidating data held by different departments

across different levels of government; and collecting data on the value of

preventative healthcare and the primary care function of GPs.

Harmonisation of the safety nets in

Australian healthcare

2.72

The committee heard that there is scope for government to harmonise the

different safety nets in the healthcare system. This would protect people from

unaffordable costs, especially for the cost ofco-payments not fully covered by

or outside Medicare. It could also reduce the current duplication of

administration between the existing MBS and PBS safety nets.[66]

2.73

Dr Duckett told the committee:

Basically, at the moment, there is a separate safety net for

Medicare, the MBS, and there is a separate safety net for the Pharmaceutical

Benefits Scheme, but there is no safety net for allied health costs—dental

costs or something like that. One of the things that the [National Health and

Hospitals Reform Commission] recommended was that there should be harmonisation

of the safety nets so that if you have racked up a huge amount on

pharmaceuticals you might be able to get medical services at no cost to

yourself sooner. We said that we need to be looking at how the existing safety

nets work together with some of the other programs—I think the words that the [NHHRC]

used were 'the patchwork of government programs'—that meet the cost of some

services like diabetes equipment. The incidence of these things can be really

detrimental to some people with, say, diabetes. The two safety nets were

developed differently and structured differently but they are still run by the

same department, so there ought to be some sort of harmonisation of the two,

especially with the phasing out of the tax rebates for medical expenses.[67]

2.74

However, Dr Duckett advised that, although reform was necessary, any

harmonisation of Medicare safety nets would require careful planning and design

by government to ensure individuals are not disadvantaged.[68]

Committee view

2.75

The MBS and PBS provide very different safety nets that support users

with high medical costs. However, because they are not harmonised, many users

fall through the cracks and receive less support than they should – especially

where medical conditions accrue high costs from both medical services and

pharmaceutical prescriptions.

Recommendation 5

2.76

The committee recommends that the government explore the effectiveness

of the safety nets relating to medicines and primary care, including the

consideration of potential options for improving access and reducing

out-of-pocket costs to patients.

Conclusion

2.77

The committee notes that Australia's health expenditure is not high by

international standards and that its healthcare system is reasonably efficient.

However, the committee acknowledges the challenges that the health system

faces, including the ageing of the population and the rollout of new programs

such as the NDIS.

2.78

The committee believes it is timely to start a conversation about the

healthcare system Australians want to have in the future, including the challenges,

opportunities, how to ensure fairness and equity and how this system should be

financed. The conversation started by the commission process, including the

suggestions made to it by individuals and organisations, is welcome. However,

the committee is concerned that this conversation will be cut short by the

government when the recommendations of the commission are made public.

2.79

The committee is concerned that the commission will take a quick fix

approach for savings that will not improve the health of Australians over the

long term. It urges the government to look to the long-term viability of our

healthcare system, especially by considering improvements to preventative and

primary care to alleviate future cost pressures.

2.80

The committee supports greater efficiency in expenditure and the delivery

of health services, as long as these efficiencies provide for:

-

Medicare to remain the cornerstone of the healthcare system;

-

no reduction in the overall Commonwealth health funding envelope,

and that the proceeds of any efficiencies are reinvested directly into the

health sector;

-

no degradation in the quality of healthcare and good health

outcomes; and

-

no additional barriers to access healthcare put in place for low

socio-economic, disadvantaged or regional populations.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page