Chapter 3

Work of the committee in 2013-14

3.1 This chapter provides information about the work of the committee during

2013-14, including the major themes and scrutiny issues arising from the

legislation examined by the committee.

Legislation considered

3.2

During the reporting period, the committee assessed a large number of

bills and legislative instruments in order to determine their compatibility

with Australia's international human rights obligations.

3.3

Table 3.1 shows the total number of bills, Acts and legislative

instruments considered, as well as how many in each category were found to

raise no human rights issues, or raised human rights issues in relation to

which the committee made advice-only comments to, or required a response from,

the legislation proponent.

Table 3.1: Legislation

considered during the reporting period

|

|

Total considered

|

No human rights issues

|

Advice-only comment

|

Response required

|

|

Bills and Acts

|

191

|

110

|

10

|

71

|

|

Legislative

instruments

|

1954

|

1887

|

30

|

37

|

Reports tabled during the period

3.4

The committee tabled eight reports during the reporting period, from the

First Report of the 44th Parliament to Eighth Report of

the 44th Parliament.[1]

Commonly engaged rights

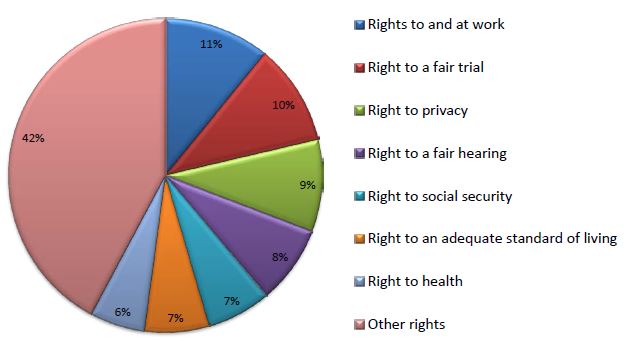

3.5

The most commonly engaged human rights identified in legislation during

this period were spread across both civil and political rights and economic,

social and cultural rights. These were:

-

rights to and at work;[2]

-

right to a fair trial;[3]

-

right to privacy;[4]

-

right to a fair hearing;[5]

-

right to social security;[6]

-

right to an adequate standard of living;[7]

and

-

right to health.[8]

3.6

During the reporting period, the above seven rights accounted for 58 per

cent of rights engaged within both primary and delegated legislation.

3.7

Figure 3.1 shows the breakdown of human rights engaged by the legislation

examined by the committee in the reporting period.

Figure

3.1: Human rights engaged by legislation in 2013-14

Major themes

3.8

Three significant areas of legislative activity in the reporting period

were in the areas of industrial relations, migration, and social security. The

committee's examination of legislation relating to these policy areas

highlighted a number of significant intersections with Australia's

international human rights obligations.

Industrial relations legislation

3.9

The committee examined a series of bills seeking to implement the

government's industrial relations policy: the Fair Work (Registered

Organisations) Amendment Bill 2013; the Building and Construction Industry

(Improving Productivity) Bill 2013 and the Building and Construction Industry

(Consequential and Transitional Provisions) Bill 2013; and the Fair Work

Amendment Bill 2014.[9]

3.10

The measures in these bills included the establishment or

re-establishment of bodies with investigative and information-gathering powers

to regulate registered organisations (including unions) and persons engaged in

the building and construction industry, and measures relating to industrial

action and right of entry for unions.

3.11

Human rights commonly engaged by these bills included: the right to work

and rights at work; the right to freedom of association (including the right to

form and join trade unions); the right to a fair trial (including the right to

be presumed innocent); the right to privacy; the right against

self-incrimination; the right to freedom of assembly; the right to freedom of

expression; the right to equality and non-discrimination; and the right to a

fair hearing.

3.12

The committee generally agreed with the statements of compatibility for

the bills that the measures being implemented pursued legitimate objectives for

the purposes of international human rights law, and were rationally connected

to those objectives (that is, the measures appeared likely to achieve their

stated objectives).

3.13

However, the committee's assessments raised significant concerns as

to the proportionality of the measures, and particularly whether they

represented the least rights restrictive way of achieving their stated

objectives. In particular, the coercive information-gathering and enforcement

powers conferred on industrial oversight bodies gave rise to significant human

rights concerns because of their breadth, their application to civil

wrongdoing as well as serious criminal offences, the limited procedural

safeguards restricting and monitoring their use, the abrogation of the right of

persons not to incriminate themselves, and the significant maximum penalties

available for a failure to cooperate.

Migration legislation

3.14

The committee examined a significant number of bills and legislative

instruments seeking to implement the government's migration policies, including

changes to the handling of applications for protection and humanitarian visas,

the mandatory detention regime, and the re-introduction of temporary protection

visas.[10]

3.15

Human rights engaged by this legislation included the right to humane

treatment in detention; the right to equality and non-discrimination; the right

not to be arbitrarily detained; the obligation of non-refoulement; the

obligation to consider the best interests of the child; the right to protection

of the family; the right to freedom of movement; the right to a fair hearing;

the right to social security and an adequate standard of living; the right to

education; and the right to work.

3.16

While international law does not provide a general right of entry to a country

for persons who are non-citizens or permanent residents, Australia has

obligations under international human rights law to any person within its

jurisdiction, regardless of citizenship. In the migration law context,

non-refoulement obligations towards non-citizens are particularly important as

they are absolute and may not be subject to any limitations. In numerous instances, the

committee emphasised that effective and impartial review by a court or tribunal

of decisions to deport or remove a person, including merits review in the

Australian context, is integral to complying with non-refoulement obligations.[11]

3.17

The committee's assessments of legislation in this area also frequently

emphasised that limitations on rights must be prescribed by law and be sufficiently

clear to meet the quality of law test. Similarly, safeguards to ensure these

limitations are proportionate should be included in legislation, and not left

to administrative or ministerial discretion.[12]

3.18

The committee also examined whether legislative measures in this area disproportionately

affected vulnerable groups, such as women, children or refugees. Such impacts

may arise in the implementation of migration policy especially where distinct

legal arrangements are in place for different categories of persons, such as

classes of visa holders. An example of this was the Migration Amendment

(Bridging Visas—Code of Behaviour) Regulation 2013 [F2013L02102] and Code of

Behaviour for Public Interest Criterion 4022—IMMI 13/155 [F2013L02105], which

implemented a code of conduct applying to certain visa holders.[13]

Social security legislation

3.19

The committee examined a significant number of bills seeking to

implement the government's social security polices, including: the Social

Services and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2013; Social Security Legislation

Amendment (Green Army Programme) Bill 2014; Social Security Legislation

Amendment (Increased Employment Participation) Bill 2014; Paid Parental Leave

Amendment Bill 2014 and Family Assistance Legislation Amendment (Child Care

Measures) Bill 2014.[14]

3.20

These bills sought to give effect to a range of measures affecting

social security benefits, in many cases introducing targeted measures with the

intention of reducing public expenditure on social security payments. Along

with the right to social security, this legislation engaged the right to an

adequate standard of living, the right to work and to just and favourable

conditions of work, and the right to equality and non-discrimination.

3.21

In seeking to reduce levels of social security entitlements and

payments—for example, by pausing indexation on certain social security

payments—many of the measures in the bills were properly characterised as

retrogressive measures for the purposes of international human rights law.[15]

While permissible, retrogressive measures are required by international human

rights law to be justified as being in pursuit of a legitimate objective, and

being rationally connected and proportionate to, achieving that objective.

3.22

In this respect the committee has consistently recognised that under

international human rights law budgetary constraints are capable of providing a

legitimate objective for the purpose of justifying reductions in government

support that impact on economic, social and cultural rights. However, the

committee has routinely requested further information where it is not clear that

such measures are proportionate to their stated objective, and particularly where

vulnerable groups, such as women, children or indigenous people, would appear

to be affected.

3.23

The committee's requests for information from ministers in relation to

measures implementing social security policy also routinely seek information as

to whether less rights restrictive measures to achieve particular objectives

were available and, if so, why they were not adopted.

Scrutiny issues

3.24

During the reporting period, the committee identified a number of issues

that posed particular challenges for the committee, as well as for legislation

proponents and departments. These included timeliness; the quality of

statements of compatibility; human rights scrutiny of appropriation bills;

instruments relating to the autonomous sanctions regime; and instruments

relating to the Stronger Futures package of legislation.

Timeliness

3.25

The committee seeks to conclude its consideration of bills while they

are still before the Parliament, and its consideration of legislative instruments

within the timeframe for disallowance (usually 15 sitting days). In both cases,

the committee's approach seeks to ensure that its reports on the human rights

compatibility of legislation are available to inform the debates of both Houses

of the Parliament.

3.26

Accordingly, the responsiveness of legislation proponents to the

committee's requests for responses regarding human rights concerns is critical to

the effectiveness of the scrutiny process. However, while the committee stipulates

a deadline by which it expects a response be provided, there is no legal or

procedural requirement to ensure that a legislation proponent provides their response

in this time period.

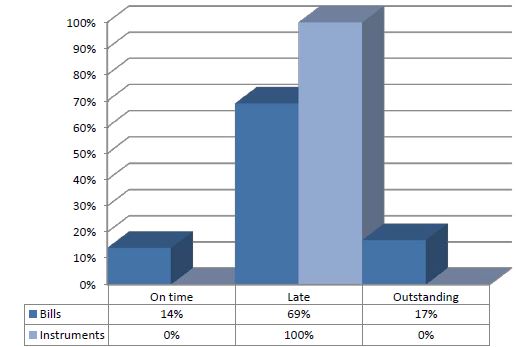

3.27

Timeliness was a significant issue during the reporting period, with responses

from legislation proponents often not being received until well after the committee's

deadline and, on occasion, not until after the bill or timeframe for

disallowance had passed.

3.28

Responses were requested in relation to 58 bills in the reporting period

(before 30 June 2014). Only eight of these (14%) were provided to the

committee by the requested date. Responses in relation to 40 bills (69%) were

provided to the committee after the requested date. The remaining 10 bills

(17%) still had responses outstanding at 30 June 2014 (see figure 3.2).

3.29

Responses were requested in relation to 44 legislative instruments in

the reporting period. No responses relating to these instruments were provided

to the committee by the requested date. All responses were provided to the

committee after the requested date; there were no responses outstanding at

30 June 2014 (see figure 3.2).

Figure

3.2 Percentage of responses received by due date

Statements of compatibility

3.30

The quality of statements of compatibility continued to improve over the

reporting period.

3.31

In many cases, statements of compatibility provided sufficient

information on proposed measures limiting human rights for the committee to

conclude its examination without requesting further information from the

legislation proponent. For example, the executive summary to the First

Report of the 44th Parliament noted that the discussion of civil

penalties and criminal process rights in the statement of compatibility

accompanying the Clean Energy Legislation (Carbon Tax Repeal) Bill 2013 was particularly

useful in assisting the committee with its task.[16]

3.32

However, a significant number of bills and legislative instruments

during the reporting period failed to provide sufficient information or

supporting evidence to justify potential limitations of human rights. In both

its First Report of the 44th Parliament and Second Report

of the 44th Parliament, the committee observed that the quality

of a number of statements of compatibility fell short of the committee's

minimum expectations.[17]

In particular, the committee noted that proponents of legislation often claimed

that measures engaging human rights were 'reasonable, necessary and

proportionate' without providing any supporting analysis or empirical evidence.

3.33

Further, statements of compatibility often stated that measures did not

engage human rights where rights were clearly engaged.[18]

3.34

In a number of cases, the committee noted that additional information

provided by the legislation proponent addressed the committee's concerns, but

should have been included in the statement of compatibility for the bill or

instrument in the first instance.[19]

3.35

Where inadequacies in statements of compatibility were identified, the

committee continued its practice of sending advisory letters to legislation

proponents to provide guidance on the preparation of, and requirements for,

statements of compatibility.

Human rights scrutiny of

appropriation bills

3.36

In the 43rd Parliament the committee set out its initial

views on the human rights implications of appropriation bills, and recommended

that human rights impact assessments be expressly incorporated in portfolio

budget statements to ensure that human rights are properly reflected in the

budgetary process.[20]

3.37

The committee's dialogue with the Minister for Finance on appropriation

bills continued in the reporting period. In its Third Report of the 44th

Parliament the committee wrote to the new Minister for Finance on the

question of whether the budgetary processes should expressly take account of

human rights considerations.[21]

3.38

The minister's response was considered alongside the committee's analysis

of new appropriations bills in its Eighth Report of the 44th

Parliament. The minister considered that requiring human rights impact

statements to be included in portfolio budget statements was 'neither

practicable nor appropriate',[22]

but offered the committee a departmental briefing on aspects of appropriation

bills and their explanatory memoranda. In its concluding comments in this

report, the committee noted that further consultation was required to assess

how portfolio budget impact statements and explanatory memoranda could assist

the committee in its examination of appropriation bills for compatibility with

human rights.

Autonomous sanctions regimes

3.39

In the previous reporting period the committee considered a number of instruments

made under the Autonomous Sanctions Act 2011 and the Charter of the

United Nations Act 1945.[23]

The committee sought further information from the Minister for Foreign Affairs

as to the compatibility of the instruments with multiple human rights.

3.40

More broadly, however, the committee considered that it is necessary to

assess whether the sanctions regimes as a whole are compatible with human

rights, before it is able to assess the compatibility of individual

instruments. The committee therefore also requested that the minister comprehensively

review the autonomous sanctions regimes with respect to Australia's international

human rights obligations. The former minister responded stating that he had

instructed the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade to carefully consider this

recommendation.

3.41

During the reporting period, the committee wrote to the new Minister for

Foreign Affairs to draw her attention to the committee's consideration of these

matters and to reiterate its request for a review in relation to the sanctions

regimes.[24]

As at the end of the reporting period, the committee had not received a

response from the minister.

3.42

Pending the minister's response, the committee continued to defer

its consideration of instruments relating to the sanctions regimes.[25]

These new instruments expanded or applied the operation of the sanctions regimes

by designating or declaring that a person or entity is subject to the sanctions

regime, or by amending the regime itself. Designating a person or entity has

the effect that the assets of

the designated person or entity are frozen. Declaring a person has the effect

of preventing that person from travelling to, entering or remaining in

Australia. Additionally, sanctions can restrict

or prevent the supply, sale or transfer or procurement of goods or services.

3.43

The broad effects of the sanctions regimes as implemented in both

primary and delegated legislation therefore engage and limit multiple human

rights. These include the right to privacy; right to a fair hearing; right to

protection of the family; right to equality and non-discrimination; right to an

adequate standard of living; right to freedom of movement; and the prohibition

against non-refoulement.

Review of Stronger Futures

legislation

3.44

During the 43rd Parliament the committee conducted an inquiry

into the Stronger Futures in the Northern Territory Act 2012 and related

legislation.[26]

The Stronger Futures measures apply to the Northern Territory and relate to

areas such as tackling alcohol abuse in Aboriginal communities; income

management; school attendance; certain land reform measures; food security

measures relating to the licensing regimes for food stores in certain areas; and

amendments relating to the extent to which customary law may be taken into

account in bail and sentencing decisions. The committee received a number of

submissions to this inquiry from various groups concerned about the human

rights compatibility of the measures.

3.45

The committee determined that a number of rights were engaged by the

measures, including the right to self-determination; right to equality and non‑discrimination;

right to equal protection before the law; right to social security; right to an

adequate standard of living; and right to privacy. The committee made a number

of findings and recommendations as to the human rights compatibility of the

legislation, and determined that it would subsequently review the measures to consider

the latest evidence as to the effectiveness and ongoing necessity of the

measures.

3.46

The new committee established at the beginning of the 44th

Parliament commenced this review in July 2014. Accordingly, during the

reporting period, the committee deferred a number of pieces of legislation on

the basis that they would be considered as part of the review.[27]

Additional work of the committee

3.47

During the reporting period the committee endeavoured to broaden public

awareness of, and engagement with, the committee, by creating a number of

resources to assist members of the public in understanding the committee's work.

3.48

The committee established an Index of bills, which lists all

bills introduced during the 44th Parliament and the action taken by

the committee. It identifies the human rights that have been engaged and the

relevant reports where the committee's full analysis may be found. The Index

of bills is useful for those who are interested in finding the committee's

analysis on a particular bill.[28]

3.49

In March 2014 the committee published a Guide to human rights,

which provides an introduction to the key human rights considered by the

committee. The Guide to human rights is discussed in more detail at

Chapter 2 of this report, and the latest version is available on the

committee's website.[29]

3.50

The committee also established a mailing list, which notifies

subscribers of the committee's work. Subscribers are notified when the

committee tables its regular scrutiny reports, as well as other reports, and

when the committee publishes new resources (such as the Guide to human

rights mentioned above).

3.51

Further, the committee began to have its work posted on social media

during this period. For example, the official parliamentary Twitter accounts

began to announce when the committee's reports had been tabled.

The Hon Philip Ruddock MP

Chair

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page