Bills Digest No. 76,

2017–18

PDF version [369KB]

Claire Petrie

Law and Bills Digest Section

Hazel Ferguson and Henry Sherrell

Social Policy Section

7

February 2018

Contents

Purpose of the Bills

Commencement details

Background

The impetus for the

Bills—Commonwealth funding arrangements for skills training

The status of skills reform

National skill shortages and the

decline in apprenticeship numbers

Table 1: major national skill

shortages, Australia, 2016–17

Figure 1: total apprenticeship

commencements and completions 1963–2016

Figure 2: trade (apprenticeships) and

non-trade (traineeship) commencements 1995–2016

National skill shortages and

immigration policy

Training benchmarks

Table 2: national Partnership on the

Skilling Australians Fund 2007–18 Budget State allocation estimates, including

average yearly funding comparison with National Partnership Agreement on Skills

Reform(a)

Committee consideration

Education and Employment Committee

Senate Standing Committee for the

Scrutiny of Bills

Policy position of non-government

parties/independents

Position of major interest groups

Skilling Australians Fund

Skilling Australians Fund—Charges

Financial implications

Statement of Compatibility with Human

Rights

Parliamentary Joint Committee on

Human Rights

Key issues and provisions

Note about contingent amendments

Nomination approvals

Nomination training contribution

charge

Requirement to pay the NTC charge

Charges Bill

Penalties and Commonwealth liability

Skilling Australians Fund Revenue and

visa trends

Permanent sponsored visas

Temporary sponsored visas

Figure 3: Primary 457 visas granted

each quarter 2005–2017

Labour Market Testing requirements

Background

Existing provisions

Proposed amendments

Application provisions

Concluding comments

Date introduced: 18

October 2017

House: House of

Representatives

Portfolio: Immigration

and Border Protection

Commencement: At

various dates, as set out in the digest.

Links: The links to the Bills,

their Explanatory Memorandum and second reading speeches can be found on the home

page for the Migration

Amendment (Skilling Australians Fund) Bill 2017 and Migration

(Skilling Australians Fund) Charges Bill 2017, or through the Australian

Parliament website.

When Bills have been passed and have received Royal Assent,

they become Acts, which can be found at the Federal Register of Legislation

website.

All hyperlinks in this Bills Digest are correct as

at February 2018.

Purpose of

the Bills

The purpose of the Migration Amendment (Skilling

Australians Fund) Bill 2017 (SAF Bill) is to amend the Migration Act 1958

(the Act) to:

- require

employers who nominate a worker for a temporary or permanent skilled visa to

pay a ‘nomination training contribution charge’, which is to be imposed by the

Migration (Skilling Australians Fund) Charges Bill 2017

- clarify

that a person does not need to be approved as a sponsor at the time of lodging

a nomination application and

- give

the Minister the power to determine by way of legislative instrument, requirements

for undertaking, and providing evidence of, Labour Market Testing.

The purpose of the Migration (Skilling Australians Fund)

Charges Bill 2017 (Charges Bill) is to provide for the imposition of the

nomination training contribution charge, enable the amount of the charge to be

prescribed by the regulations, and specify a limit on the charge.

The Bills were introduced in the House by the Minister for

Immigration and Border Protection. From 20 December 2017, this portfolio

is part of the Home Affairs portfolio.

Commencement

details

Sections 1 to 3 of the SAF Bill commence on Royal Assent.

Schedule 1 commences on Proclamation or six months after Royal Assent,

whichever occurs first. Schedule 2 will commence at the same time as Schedule 1,

but:

- Part

1 of Schedule 2 will not commence at all if the Migration Amendment (Family

Violence and Other Measures) Bill 2016 (Family Violence Bill) has already been

passed and commenced and

- Part

2 of Schedule 2 will not commence at all if the provisions of the Family

Violence Bill have not yet commenced.[1]

Sections 1 and 2 of the Charges Bill commence on Royal

Assent. Sections 3 to 10 commence at the same time as Schedule 1 of the SAF

Bill—that is, on Proclamation or six months after Royal Assent, whichever

occurs first.[2]

Combined, these two Bills will facilitate the introduction

of the training levy which commences March 2018 and supports the new Temporary

Skill Shortage (TSS) Visa.

Background

The impetus

for the Bills—Commonwealth funding arrangements for skills training

The SAF Bill and Charges Bill respond to the Government’s

2017–18 Budget commitment to provide a new fund for skills training, following

the expiry of the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) National

Partnership Agreement on Skills Reform (NPASR) on 30 June 2017.[3]

Under the Intergovernmental

Agreement on Federal Financial Relations (IGA-FFR), the Commonwealth

supports states and territories to deliver skills training services through National

Specific Purpose Payments (SPPs) under the National

Agreement for Skills and Workforce Development (NASWD). From 2017–18 to

2020–21, approximately $1.5 billion in SPPs will go to the states and territories

each year under the NASWD.[4]

The NASWD aims to:

- halve

the proportion of Australians nationally aged 20–64 without qualifications at

Certificate III level and above between 2009 and 2020

- double

the number of higher level qualification completions (diploma and advanced

diploma) nationally between 2009 and 2020

- improve

the proportion of VET graduates with improved employment status after training.[5]

To support the aims of the NASWD, the Commonwealth

committed $1.75 billion through National Partnership Payments (NPPs) under the

NPASR from 2012–13 to 2016–17, to improve the accessibility, transparency,

quality, efficiency and responsiveness of the vocational education and training

(VET) sector.[6]

NPASR implementation plans varied according to jurisdictional needs, however

the overall focus was on achieving structural change through improved quality

assurance, data collection and management, and financing arrangements,

including the extension of income contingent loans (then VET FEE-HELP) to

government-subsidised Diploma and Advanced Diploma courses, and a limited

number of Certificate IV courses (where this had not already been implemented

at the time of NPASR commencement).[7]

The status of skills reform

Although

2015 saw the Review of the National Partnership Agreement on Skills Reform (the NPASR Review) raise a number of concerns about the NPASR

in relation to quality and transparency, especially in light of growing

concerns about unscrupulous providers accessing VET FEE-HELP, states and territories

met or exceeded all agreed outcomes.[8]

A number of key national reforms were implemented, including the introduction

of the national My Skills website and Unique Student Identifier (USI).[9]

However, consistent with the broader concerns identified in

the Review, progress against the higher level NASWD objectives is not on track,

with growth in attainment slower than expected, and employment outcomes

worsening over the term of the agreement.[10]

In particular:

- although

the proportion of 20 to 64 year old persons without a non-school qualification

at Certificate III or above has fallen substantially, from 47.1 per cent in

2009 (NASWD base year) to 38.4 per cent at May 2017, the trajectory has not

been sufficient to put jurisdictions on track to achieve the objective of

halving this figure by 2020[11]

- although

the number of higher level qualification completions (diploma and advanced

diploma) has increased from 53,974 in 2009 to 62,100 in 2015 (latest year in

COAG reporting), numbers have been declining in recent years from a peak of

88,783 in 2012[12]

- labour

market outcomes for VET graduates between 20 and 64 years worsened between 2008

and 2015, with improved graduate employment outcomes (being employed at a

higher skill level after training or receiving a job-related benefit) declining

8.1 percentage points, from 67.6 per cent to 59.5 per cent of graduates.[13]

National skill shortages and the decline in

apprenticeship numbers

At a national level, the effect of the uneven progress on skills

reform, along with the emphasis on expanding access to higher-level

qualifications under the NPASR has partly been felt in skill shortages in

trades. While there are few areas of major skill shortage in Australia, as can

be seen in Table 1 below, ‘widespread shortages [are] apparent for just 5

assessed Professions (one of the lowest levels recorded over the past decade),

but 22 Trades Worker occupations.’[14]

Table 1: major national skill shortages, Australia,

2016–17

|

Professions

|

Technicians

|

Trades Workers

|

|

Architect

|

Construction Estimator

|

Air Conditioning and refrigeration mechanic

|

Pastrycook

|

Butcher or smallgoods maker

|

Telecommunications trades worker

|

|

Audiologist

|

|

Arborist

|

Roof tiler

|

Cabinetmaker

|

Vehicle painter

|

|

Sonographer

|

|

Automotive electrician

|

Sheet Metal trades worker

|

Fibrous plasterer

|

Wall and floor tiler

|

|

Surveyor

|

|

Baker

|

Solid plasterer

|

Glazier

|

Motor mechanics

|

|

Veterinarian

|

|

Bricklayer

|

Stonemason

|

Hairdresser

|

Painting trades worker

|

|

|

|

Locksmith

|

Panel Beater

|

|

|

Source: Department of Employment, The

Skilled Labour Market: A pictorial overview of trends and shortages, 4

September 2017, slide 38. This list has no status for immigration—see below for

more information.

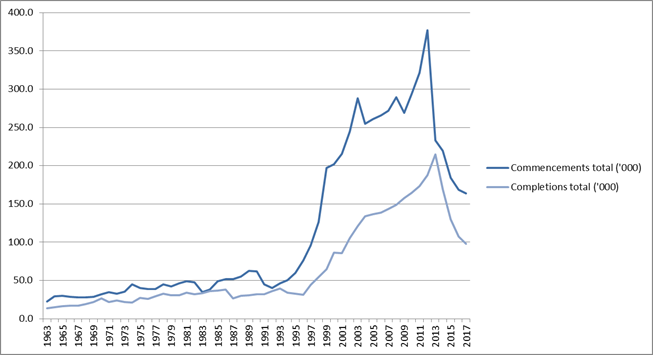

Recent years have seen a significant decline in the take

up of apprenticeships to supply these trades, from a top

of 376,800 in 2012, to 164,000 in 2017, with a corresponding decline in

apprenticeship completion rates (see Figure 1 below).[15]

Figure 1: total apprenticeship commencements and

completions 1963–2017

Source: Parliamentary Library based on National Centre for

Vocational Education Research (NCVER), ‘Historical

time series of apprenticeships and traineeships in Australia from 1963 to 2017’,

NCVER website, 7 December 2017, Table 4; Table 6.

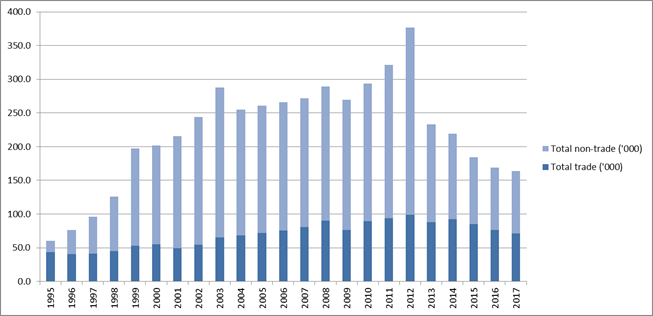

However, as can be seen in Figure 2 below, decreases were

most dramatic in non-trade (sometimes known as traineeship) commencements,

where some policy analysts have argued that incentive payments may have been

more of a factor in employer decision-making than workforce investment or need.[16]

Figure 2: trade (apprenticeships) and non-trade (traineeship)

commencements 1995–2017

Source: Parliamentary Library based on National Centre for

Vocational Education Research (NCVER), ‘Historical

time series of apprenticeships and traineeships in Australia from 1963 to 2017’,

NCVER website, 7 December 2017, Table 11.

In part,

these decreases reflect judgments about employment prospects, with the

worsening outcomes for VET graduates cited above reflecting stronger employment

growth for professionals (35 per cent) than technicians and trade workers

(9 per cent) over the decade between May 2007 and May 2017.[17]

However, as apprentices are engaged by employers with funding and other support

from government, the number of apprentices and trainees is also influenced by

Commonwealth and state and territory funding decisions.

National

skill shortages and immigration policy

In addition to qualification funding, immigration policy

has been used by successive Australian governments in response to employer

concerns about skill shortages.

Ruhs and Anderson find ‘employer demand for migrant

workers has become a key feature of labour markets in high income countries.’[18]

However assessing the claims of employers in relation to the existing skills

(and labour) available from the domestic labour force is ‘highly contested’.[19]

The 457 visa, a temporary, sponsored skilled visa

category, was introduced in 1996 by the Howard Government following the Roach

Review:

A country of Australia’s size cannot be expected to be

completely self-sufficient at the leading edge of all skills in the area of key

business personnel... Thus there will be a need for Australia to import certain

skills, in much the same way as Australia is developing skills to export.[20]

According to the most recent review led by John Azarias, the

introduction of the 457 visa program in 1996 was to better ‘facilitate the

temporary entry of highly-skilled senior executives and specialists’.[21]

However in response to ‘skill shortages experienced in the Australian labour

market in the 2000s’ additional occupations were made eligible for employer

sponsorship.[22]

While there are 28 occupations on the Department of

Employment’s list of major skill shortages (Table 1 above), immigration policy

has used more extensive lists of occupations for employers to hire temporary

skilled migrants.[23]

The current occupation lists—the Medium and Long-term Strategic Skills List and

the Short-term Skilled Occupation List—include 461 occupations.[24]

In April 2017, these occupation lists replaced the Consolidated Sponsored Occupation

List which contained 651 occupations.[25]

This shows different approaches to skills policy across

government portfolios. The 457 visa program (to be replaced by the Temporary

Skills Shortage program from March 2018) allows an employer to sponsor a

temporary migrant where no Australian resident is available for a nominated

job. [26]

An occupation must be nominated by the employer, which the migrant must be

qualified to perform.

However while the occupational lists used for this visa

program are much more extensive than those constructed by the Department of

Employment, additional regulations within the 457 visa program are designed to

ensure employers seek to hire for genuine skill shortages. These include the

requirements for employers to pay temporary migrants the same salary and grant

them the same conditions as existing Australian workers and for employees to be

genuinely skilled applicants.[27]

Training

benchmarks

One program requirement for the current 457 visa program

is to meet the training benchmarks. This eligibility criteria for employers has

been in place since 2009 to promote training opportunities for existing

Australian residents.[28]

The training benchmarks require employers who hire temporary skilled migrants

to either pay two per cent of their payroll to a training fund or show one per

cent of their payroll is spent on training activities.[29]

These are known as training benchmarks A and B respectively and designed as

skills policy to ensure employers who use the 457 visa program also demonstrate

a commitment to training local labour.[30]

From March 2018, the training benchmarks are being

abolished and replaced by the levy proposed in these Bills. In his second

reading speech for this Bill, Minister Dutton said ‘the Skilling Australians

Fund levy will fully replace these training benchmark arrangements’.[31]

Successive reports have noted the inadequacy and difficulty of assessing the

training benchmarks. The Azarias review in 2014 ‘found that there was little

support by either sponsors or labour representatives for the current training

benchmarks’.[32]

The review recommended the training benchmarks be abolished and replaced by an

annual training contribution, with the latter being the purpose of these Bills.

The proposed levy is discussed in detail under ‘Key Provisions’.

The Skilling Australians Fund

According to Senator Simon Birmingham, Minister for

Education and Training, the SAF will target declining apprenticeship numbers

through industry funded support:

we’re funding this Skilling Australia Fund via a levy on any

foreign workers that are brought in under certain visa categories, because

that’s reinforcing to businesses that if you’re not going to play a role in

helping support the training system in providing apprenticeship opportunities,

well then, you’re going to be paying more for your labour because we will be

taking the cash off you to help those who are going to help train our future

apprentices.[33]

According to the Department of Education and Training, the SAF

will support:

projects

brought forward from states and territories which support apprenticeships,

traineeships, and pre- and higher-level apprenticeships and traineeships with

the following priorities:

- occupations in demand

- occupations with a reliance on skilled migration pathways

- industries and sectors of future growth

- trade apprenticeships

- rural and regional areas

-

respect of people from targeted cohorts.[34]

Priority industries ‘include but are not limited to key

industries right across Australia, like tourism and hospitality, health and

ageing, agriculture, engineering, manufacturing, building and construction, and

the digital technologies.’[35]

Projects funded through the SAF would be in addition to existing Commonwealth,

state and territory, and employer investment in Australian Apprenticeships.[36]

While the specifics of any new Partnership Agreement are

subject to negotiation with the states and territories through the COAG Industry and Skills Council (CISC), according to the

2007–18 Budget papers the SAF, ‘when matched with funding from the States, will

support up to 300,000 more apprentices, trainees and higher level skilled

Australians over the next four years’.[37] It is not clear if the 300,000 more apprentices will be in addition to

apprenticeship numbers according to current trends—75,000 apprenticeship

commencements on average each year above trend would represent substantial

growth from a base of 168,800 commencements in 2016.

Estimated state allocations from the SAF, subject to

project approval, are provided in 2007–18 Budget paper 3, as summarised in

Table 2 below.

Table 2: national Partnership on the Skilling Australians

Fund 2017–18 Budget State allocation

estimates, including average yearly funding comparison with National

Partnership Agreement on Skills Reform(a)

| $ million |

NSW |

VIC |

QLD |

WA |

SA |

TAS |

ACT |

NT |

Total |

| 2017–18(b) |

112.2 |

88.7 |

70.1 |

37.9 |

24.5 |

7.4 |

5.7 |

3.5 |

350.0 |

| 2018–19 |

115.4 |

91.6 |

72.0 |

38.9 |

25.1 |

7.5 |

5.9 |

3.6 |

360.0 |

| 2019–20 |

125.0 |

99.7 |

77.9 |

42.1 |

27.0 |

8.1 |

6.4 |

3.8 |

390.0 |

| 2020–21 |

118.7 |

95.1 |

73.8 |

39.9 |

25.4 |

7.6 |

6.0 |

3.6 |

370.0 |

| Total |

471.3 |

375.1 |

293.8 |

158.8 |

102.0 |

30.6 |

24.0 |

14.5 |

1470.0 |

| Average total per year over four years (SAF) |

117.8 |

93.8 |

73.5 |

39.7 |

25.5 |

7.7 |

6.0 |

3.6 |

367.5 |

| Average total per year over five years (NPASR)(c) |

112.3 |

87.0 |

71.4 |

36.5 |

25.4 |

7.8 |

5.6 |

3.6 |

349.6 |

Notes:

(a) In accordance with the IGA-FFR, allocations are based on

the population share of each jurisdiction.

(b) $261.2 million of the 2017–18 total is budgeted to be made

up from Commonwealth appropriations, in addition to projected Fund contribution

revenues.

(c) 2012 dollars.

Source: Parliamentary Library based on Australian Government, ‘Part

2: Payments for Specific Purposes’, op. cit., p. 35; CFFR, ‘National

partnerships - skills and workforce development’, op. cit., p. 27.

However, it is unclear if NPPs

will match these estimates:

From 2018‑19, amounts available to the States from the Skilling

Australians Fund will be determined by the revenue paid into the Fund.

States’ access to the Fund will be dependent on meeting eligibility criteria

defined by the Commonwealth, including matching Commonwealth funding, achieving

outcomes, and providing up to date data on performance and spending.[38]

Although

National Partnerships by definition typically involve shorter-term funding to

deliver a project or key reform, a lack of funding stability has played a role

in the uneven progress on skills reform to this point. The

NPASR Review identified funding stability to

support VET reform as an issue to be addressed in future agreements:

Any future reform of the VET sector should be

supported with public funding that is allocated across the system in a way that

provides market stability, with reasonable long term certainty in the quantum

of funding, and takes into account all related funding channels.[39]

Thus, the potential of the SAF will be subject to

implementation arrangements which are outside the Bills, and the stability of

the industry funding source.

Committee

consideration

Education

and Employment Committee

The Bills have been referred to the Senate Standing

Committee on Education and Employment for inquiry and report by 9 February 2018.

Details are available at the inquiry

homepage.

Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

The Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

reported on the Bills on 15 November 2017. The Committee had no comment on the

Charges Bill.[40]

In relation to the SAF Bill, the Committee raised concerns about the scope of proposed

section 140ZN of the Act (at item 12 of Schedule 1), which enables

the regulations to provide for the payment of a penalty in relation to an

underpayment of the nomination training contribution charge. The Committee

sought the Minister’s advice as to why the Bill delegates to regulations the

power to impose a penalty, without setting any upper limit on the level of the

penalty.[41]

The Minister responded to the Committee’s concerns on 4

December 2017, advising that he would consider moving an amendment to the Bill

to set an upper limit on the level of the penalty that may be prescribed in the

regulations.[42]

Policy

position of non-government parties/independents

Whilst substantive comment on the Skilling Australians Fund

Bills has been limited, Senator Doug Cameron, Labor’s Shadow Minister for

Skills, TAFE and Apprenticeships, has outlined a number of concerns about the

proposed funding mechanism and likely outcomes of the SAF:

The proposed agreement and funding mechanism, the Skilling

Australians Fund, has been widely derided as unworkable, inadequate and

insecure.

The Skilling Australians Fund relies entirely on fees paid by

skilled overseas workers. The contradiction of relying on fees paid by foreign

workers filling skills gaps for Australia’s skills development seems lost on

the Turnbull government.

The government’s claim that the Fund will create an

additional 300,000 apprenticeships and traineeships is unrealistic. The rate of

apprenticeships will have to rise from 2.2% of current jobs to 30% for all new

jobs to meet this target.[43]

Senator Cameron has further stated:

The Skilling Australians Fund will fail to fix the systemic

problems that exist—instead it will exacerbate them.

Labor has no argument with charging employers for skilled

worker visas - and ensuring that money goes to skill development.

However, the proposal that a skilled worker levy would be the

sole source of Commonwealth revenue for skills development is astounding.[44]

Position of

major interest groups

Skilling

Australians Fund

Many stakeholders from within the VET sector, including TAFE Directors Australia (TDA) and the Australian Council for Private

Education and Training (ACPET), welcomed the initial announcement of the SAF.[45] Executive

Officer of the National Apprentice Employment Network (NAEN), Lauren Tiltman,

stated ‘[t]his is a welcome focus on areas of genuine economic and social need

with real potential to rebuild apprentice and trainee numbers which have been

in decline.’[46]

However, following introduction of the Bills, VET stakeholders

have raised concerns about the SAF in submissions to the Senate Standing Committee

on Education and Employment inquiry into the Bills (the Inquiry). Although

outside the scope of the Bills, these submissions raise concerns about the project-based

approach to the SAF, with TDA observing:

While details of the proposed agreements are still being

negotiated, TDA is concerned that the model may result in a piecemeal approach

to reforms needed in the sector. The increased accountability and

administrative work envisaged in such projects, while primarily between levels

of government, will also flow through to TAFEs and other providers that will

likely be the delivery arm for the initiatives... TDA sees national employers as

playing a lead role in engaging apprentices and trainees, and supporting the

integrity of a national training system. However, the project model through

individual jurisdictions risks these employers needing to engage individually

with each jurisdiction. This creates a clear disincentive plus a real cost

premium, especially as each jurisdiction will pursue its priorities in

different ways. TDA recommends that governments consider a pool of funds to

support national employers.[47]

Similarly, NAEN proposes the SAF allow direct partnership

agreements with national or state organisations to address this issue:

In principle we support targeted programs that allow for

variations in regions and industries, however to limit this fund to small

projects would create a significant administrative burden. Alternatively, to

allow only larger project proposals due to administrative efficiencies, would

disadvantage those in thin markets, regional and remote employers and potential

apprentices, and small, emerging and innovative industries. NAEN calls for this

fund to allow for direct partnership agreements with national or state organisations

which have the capacity to deliver against the outcomes in the fund, at a

reduced administrative cost, while still servicing thin markets. [48]

Additionally, while stakeholders acknowledge the

importance of addressing issues in the apprenticeship system, the TAFE

submissions suggest a new Partnership Agreement should be wider in scope. TDA

states that the SAF ‘risks focusing effort

on apprenticeships and traineeships at the expense of responding to other

important priorities facing the Australian economy.’[49]

The Victorian TAFE Association ‘is supportive of the idea that the Skilling

Australians Fund help to underpin a new agreement, [but] it considers that

this must form but one ‘plank’ within a National Partnership Agreement that is

broader in scope and funding than the Skilling Australians Fund.’[50]

Skilling

Australians Fund—Charges

A number of industry stakeholders have commented on the

new levy. Peter Mares, an author on contemporary temporary migration policy,

noted in a pre-Budget article that a strengthened training obligation in the

457 visa program ‘is by far the most promising initiative to come out of the

changes to temporary migration.’[51]

However, industry stakeholders have since raised concerns about the charges. Ai

Group argued the levy is a ‘significant impost on businesses’ that will ‘add to

costs, prices and will put pressure on business margins.’[52]

The Queensland Chamber of Commerce and Industry said ‘we don’t want to see

small businesses burdened with upfront costs when there are continuing labour

issues in sectors such as hospitality, tourism and agriculture.’[53]

John Hart, of the Australian Chamber National Tourism Council said ‘this will

reduce local job numbers by limiting the ability of local businesses to grow.’[54]

The Migration Council Australia has suggested the fees

levied on permanent visas may discourage employers from sponsoring migrants for

permanent residency.[55]

In a submission to the Inquiry, the Federation of Ethnic Communities’ Councils

of Australia (FECCA) recommended that an alternative funding source for the SAF

be found, arguing:

The proposed levy presents further risks to migrant workers

including the increased possibility of salary deductions (wage theft) and a

rise in racism and discrimination. Migrant workers are already overwhelmingly

the victims of widespread, systematic and long term wage theft. FECCA is

particularly concerned that placing a levy on their employers will result in

greater levels of wage theft and other forms of exploitation as the employers

‘pass on’ the associated cost of hiring migrant workers.’[56]

In contrast to concerns about the cost of the levy,

concerns have also emerged about a mismatch between the revenue it is likely to

generate, and the level of funding required to adequately resource the SAF. The

Australian Council of Trade Unions ‘fully supports the concept of an

employer-paid levy for 457 visas’[57]

however voiced concern in the wake of the Budget that the levy may raise less

revenue than previous skills funding mechanisms.[58]

In submissions to the Inquiry, VET stakeholders echo these concerns, suggesting

SAF projects may be undermined by unstable funding. For example, the Victorian

TAFE Association states:

[I]f this need for this policy initiative is established,

then its future sustainability and funding should not hinge upon the ability to

raise revenues through new migration charges... The Victorian TAFE Association

considers that the levels of funding provided should first and foremost be

driven not by the amount of money raised by migration charges but by the level

required to train and educate Australians that maximises their contribution to

Australia’s economic success, future productivity and growth.[59]

To address this, NAEN suggests:

[T]he government should guarantee a minimum contribution to this

fund in the absence of funding provided through these bills. The VET sector

should never be in a position where the best it can do to ensure sustainable

funding for apprentices, going forward is to encourage increased skilled

migrant employment. That would counter the primary purpose of this fund.[60]

Additionally, Peter Noonan, professorial fellow at the

Mitchell Institute for Health and Education Policy, has argued that

uncertainties about revenue for the SAF pose a challenge for the development of

a partnership agreement with the states and territories to distribute the SAF:

revenue for the fund will be highest when skilled migration

is highest, and lowest when employment of locally skilled workers is highest.

That means the revenue stream for the fund will be counter-cyclical to the

purpose for which it was established: to increase the proportion of locally

trained workers and to lessen reliance on temporary skilled migration visas.

Unless the Commonwealth guarantees funding levels and continues to make up any

shortfall in the revenue, it will be difficult, if not impossible, for the

Commonwealth to enter meaningful, bilateral agreements with the states through

the fund.[61]

In a joint post-budget press release in May, Victorian Skills

and Training Minister Gayle Tierney, Queensland Minister for Training and

Skills Yvette D’Ath, Western Australian Minister for Education and Training Sue

Ellery and South Australian Minister for Higher Education and Skills Susan

Close raised concerns about the timing of the SAF announcement, the funding

mechanism, level of Commonwealth expenditure, and the narrower focus of the

proposed agreement compared to the NPASR.[62]

However, the 2 June 2017 CISC Communiqué indicated that in

principle agreement to progress arrangements for the SAF had been reached and ‘Ministers

directed Skills Senior Officials to work on operational details and finalising

the principles to refer to Council, in order to facilitate the drafting of an

agreement as quickly as possible.’[63]

Yet, the Northern Territory Government, in a

submission to the Inquiry, has raised concerns in relation to the charge and

a requirement to co-contribute 50 per cent of

the funding to approved projects under the proposed national Partnership

Agreement on the SAF currently being considered by First Ministers. Based on

preliminary modeling this [along with the application of the levy to state

governments] would effectively mean the Northern Territory Government would

contribute 60 per cent to the total cost of approved projects.[64]

The application of the levy to employers with substantial

ongoing investments in employee training has also raised concerns among

tertiary education stakeholders. As outlined above, under current arrangements

employers are exempt from contributing to a training fund if they can show

training expenditure equal to at least one per cent of their payroll (referred

to as ‘training benchmark B’). A number of submissions contend that employers who

meet this criterion may struggle to continue to invest in employee training in

light of the cost of the new levy.[65]

Innovative Research Universities estimates cost increases totalling $1.7

million annually, from just under $1 million in 2017 to a projected $2.7

million in 2018 across member universities under the arrangements proposed in

the Bill.[66]

Submissions to the Inquiry, including the Law Council of Australia’s, suggest

retaining training benchmark B for employers in these circumstances.[67]

Universities Australia (UA) also suggests there is a

‘policy disconnect’ in sourcing SAF revenue from employers that rely on highly

skilled migrants in professional occupations, as they are not able to draw from

the SAF.[68]

UA makes the case that as universities already play a key role in skilling

Australia’s workforce, consideration should be given to exempting them from the

levy.[69]

A number of unions expressed support for the concept of a

levy on employers who sponsor temporary migrant workers. The Electoral Trades

Union (ETU) and Australian Manufacturing Workers Union (AMWU) both noted

in-principle support for a ‘user pays’ system.[70]

However the ETU claimed the Bill creates a ‘perverse incentive’ for the

Australian Government to increase the number of temporary migrant workers in

Australia while the AMWU recommended additional requirements supporting the

employment of apprentices and trainees directly by sponsors.[71]

Financial

implications

The Explanatory Memorandum’s Financial Impact Statement

says:

The training contribution charge is expected to generate

revenue of $1.2b over the forward estimates. Expected expenditure from the

Skilling Australian Fund over the forward estimates is $1.47b.[72]

Modelling by John Ross, a higher education reporter at The

Australian, suggests the new fees ‘will not raise enough money to

finance the scheme’.[73]

In response to a Senate Estimates question, Minister Birmingham said the

Australian Government is confident of the revenue projections, developed by:

Department of Immigration based on current immigration policy

settings, reflective of recent changes to temporary worker visa arrangements

and based on their expert understanding of historical visa flows and have all

been independently verified by the Treasury through usual budget processes.[74]

As the government has not released the underlying

assumptions used for the $1.2b revenue figure raised from the levy charges, it

is not possible to analyse the individual revenue contribution by visa

category. Concern about whether the SAF will raise the revenue projected in the

Budget was not addressed in any departmental submission to the Senate inquiry. However

using a set of assumptions based on visa trends for 2015–16 and 2016–17, it is

not clear if the Budget projections would be met in 2018–19 without a change in

visa trends. This may occur via an increase in the number of visas granted

and/or an extension in time spent on TSS visas in the future. This is discussed

in more detail under Key Issues–Skilling Australians Fund revenue and visa

trends.

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed the

Bills’ compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or declared

in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The

Government considers that both Bills are compatible.[75]

Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Human Rights

The Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights has stated

that the two Bills do not raise human rights concerns.[76]

Key issues

and provisions

Note

about contingent amendments

Schedule 2 of the SAF Bill contains two

alternative sets of amendments, the commencement of which depends on the

timing of the commencement of the Migration Amendment (Family Violence

and Other Measures) Act 2017 (Family Violence Act), the Bill for

which was before the Senate at the time of writing.[77]

In summary:

- Part

1 of Schedule 2 contains amendments which will apply if the Family Violence

Act commences after commencement of the provisions in the SAF

Bill and

- Part

2 of Schedule 2 contains amendments which will apply if the Family

Violence Act commences before commencement of the provisions in

the SAF Bill.

The differences between the amendments in the two Parts

are minor. The main distinction is that certain amendments in Part 2 use

the term ‘approved work sponsor’ rather than ‘approved sponsor’.[78]

This reflects the changes proposed by the Migration Amendment (Family

Violence and Other Measures) Bill 2016, which bring family sponsors within

the sponsorship framework under Division 3A of Part 2 of the Migration

Act.[79]

As it is not intended that family visa sponsors will be required to pay the

nomination training contribution charge (NTC charge), certain provisions

under Division 3A will need to clarify that they apply only to work

sponsors. The discussion below will state in the footnotes where

two alternative items may apply, and any difference between them.

|

Nomination approvals

Under the existing sponsorship framework in the Migration

Act, a person must be approved as a sponsor before they can apply for

approval of a nomination.[80]

Section 140GB provides that an approved sponsor may nominate either:

- an

applicant (or proposed applicant) for a visa of a prescribed kind, in relation

to either the applicant’s proposed occupation, the program to be undertaken or

activity to be carried out by the applicant or

- a

proposed occupation, program or activity.[81]

The SAF Bill proposes amending subsection 140GB(1) so that

a nomination can be made by an approved sponsor, a person who has applied to be

an approved sponsor, or a person who is a party to negotiations for a work

agreement.[82]

As stated in the Explanatory Memorandum, the amendment clarifies that a person

can lodge an application for a nomination at the same time as their application

for approval as a sponsor.[83]

However, the person must be approved as a sponsor before the nomination can be

approved.[84]

Reflecting this change, the majority of items in the SAF Bill

make consequential amendments to other provisions in Division 3A to replace the

term ‘sponsor’ with ‘person’.[85]

Nomination

training contribution charge

The SAF will be funded by a new levy—the Nomination

Training Contribution (NTC) charge—paid by employers who sponsor temporary and

permanent skilled migrants on the following visas:

- the

Temporary Skill Shortage (TSS) visa

- the

Employer Nomination Scheme (ENS) visa

- the

Regional Sponsored Migration Scheme (RSMS) visa.

While the purpose and eligibility criteria of these three

visa categories vary, each requires an employer to nominate a migrant for a

visa. As part of the proposed changes, existing training requirements for

employers sponsoring migrants will be abolished. In his second reading speech,

Minister Dutton outlined the purpose of the levy as to ‘require employers

seeking to access overseas skilled workers to contribute to the broader skills

development of Australians.’[86]

He argued the existing system is ‘overly complex and lacks transparency’.[87]

Minister Dutton drew on the 2014 Azarias review of the 457

visa program as evidence for the levy. The Azarias review included a

recommendation ‘that the current training benchmarks be replaced by an annual

training fund contribution based on each 457 visa holder sponsored, with the

contributions scaled according to size of business’.[88]

Others have proposed additional reasons for introducing a

fee on employers sponsoring migrants. A previously-announced Labor policy also

sought to introduce a fee, to ‘provide a genuine price signal to employers that

they should look local first’.[89]

This is not a new policy suggestion, with a number of researchers recommending

a higher fee charged to employers to better target the bipartisan goal of

ensuring Australian citizens and permanent residents are employed as a priority

over temporary migrants.[90]

Requirement

to pay the NTC charge

Item 12 of Schedule 1 of the SAF Bill inserts proposed

Division 3B into Part 2 of the Migration Act. This deals with the

payment of the NTC charge. Proposed section 140ZM provides that a person

is liable to pay the NTC charge to the Commonwealth in relation to either:

- a

nomination made under section 140GB, where the nomination is of a kind

prescribed by the regulations[91]

or

- an

application for approval of a nomination made under the regulations or in

accordance with the terms of a work agreement, where the visa and nomination

are of a kind prescribed by the regulations.[92]

Payment of the NTC charge, where the person is liable to do

so, is one of the criteria for approval of a nomination under section 140GB.[93]

Proposed section 140ZN states that the regulations

may provide for a range of matters associated with the NTC charge, including

when the charge is due and payable; the payment method; remission or refund;

penalties for underpayment and the giving of information and keeping of records

in relation to a person’s liability to pay the charge. The Explanatory

Memorandum notes that this will allow the regulations to permit refunds (or

partial refunds) of the charge where a nomination is refused, or where the

actual period of stay of a nominated visa applicant is significantly less than

anticipated.[94]

The Law Council raised concerns that the SAF Bill does not

provide sufficient clarity about the circumstances in which a refund will be

payable, particularly in cases where a nomination or sponsorship is refused,

where a portion of the visa period granted is unused, or where a new sponsor

takes over the sponsorship of a visa holder for part of the visa period.[95]

Additionally, it noted that the comparable Immigration Skill Charge in the

United Kingdom permits refunds in circumstances including where the applicant:

- is

successful, but does not come to work for the sponsor

- changes

to another sponsor or

- leaves

their job before the end date on their certificate of sponsorship.

The Law Council recommended that consideration be given to

whether these additional reasons for refunding the NTC charge should be

incorporated into the SAF scheme.[96]

It also suggested that the Explanatory Memorandum to the SAF Bill clarify

whether business sponsors will need to pay the charge for any of the worker’s

dependents, and whether there is anything to prevent sponsors from ‘passing on’

the charge to applicants.[97]

Charges Bill

The Charges Bill provides for the imposition of the NTC

charge. Clause 7 imposes the charge, payable under section 140ZM of the Migration

Act. The Charges Bill has extra-territorial effect, which means the charge

is payable in relation to a nomination,[98]

whether it is made in or outside Australia and whether the person who is liable

to pay the charge is in or outside Australia.[99]

Clause 8 provides that the amount payable by a person

in relation to the nomination is the amount:

- prescribed

in the regulations or

- worked

out in accordance with a method prescribed by the regulations.

Subclause 8(2) states that the regulations may

prescribe different charges or methods for different kinds of visas, or

different kinds of persons. The Explanatory Memorandum notes that the

regulations may, for example, prescribe different charges in relation to

temporary and permanent visas, or different charges depending on the annual

turnover of the employer to which the nomination relates.[100]

In his second reading speech, Minister Dutton stated that

it is intended that the charge will vary depending on whether a business has an

annual turnover of more or less than $10 million.[101]

Small businesses—those with a turnover of under $10 million—will be required to

pay $1,200 per year for each temporary overseas worker, and a one-off levy of

$3,000 for each permanent overseas worker. Businesses with an annual turnover

of $10 million or more will be required to pay $1,800 per year for each

temporary worker and a one-off payment of $5,000 for each permanent worker.[102]

The amount prescribed in the regulations cannot exceed the

NTC charge limit for the relevant financial year.[103]

This limit is set out in clause 9. For the financial year beginning 1

July 2017, the limit is:

- for

a nomination relating to a temporary visa—$8,000

- for

a nomination relating to a permanent visa—$5,500.[104]

For later financial years, the NTC charge limit is to be

calculated in accordance with subclauses 9(2) to (5). The limit is

determined by multiplying the limit for the previous financial year by the

greater of 1 or the indexation factor. The indexation factor is worked out by

dividing the sum of the index numbers[105]

for the CPI quarters of the 12 month period ending 31 December before the later

financial year, by the sum of the index numbers for the CPI quarters in the 12

months ending on the previous 31 December.[106]

The Explanatory

Memorandum to the Charges Bill notes that the NTC charge limits in subclause

9(1) are approximately ten per cent above the highest NTC charge proposed

to be prescribed in the Migration Regulations, being $7,200 for temporary visas

(that is, $1,800 for a large business for the maximum visa duration of four

years) and $5,000 for permanent visas. It states that the charge limits:

...provide flexibility for the Australian Government to make

increases to the nomination training contribution charge in the

future while providing certainty for business as to the limited scope of a

potential increase.[107]

Clause 10 of the Charges Bill enables the

Governor-General to make regulations prescribing matters as required or

permitted by the Migration (Skilling Australians Fund) Charges Act 2017,

or which are necessary or convenient for carrying out or giving effect to that

Act.

Penalties and Commonwealth liability

As noted above, proposed paragraph 140ZN(e) of the Migration

Act (inserted by item 12 of Schedule 1 of the SAF Bill) enables

regulations to prescribe the payment of a penalty in relation to underpayment

of the NTC charge. Proposed section 140ZO further specifies that where

the NTC charge or an underpayment penalty is due and payable to the

Commonwealth, the amount is a debt due to the Commonwealth and may be recovered

by action in a court of competent jurisdiction.

Proposed section 140ZP relates to the liability of

the Commonwealth to pay the NTC charge in relation to its own nominations under

section 140ZM. The Explanatory Memorandum notes that the Commonwealth cannot

make itself liable to pay Commonwealth taxes or fees.[108]

However, proposed subsection 140ZP(1) states that it is Parliament’s

intention that the Commonwealth should be notionally liable to pay the NTC

charge. The Finance Minister may make such written directions ‘as are necessary

or convenient’ for carrying out or giving effect to this intention.[109]

Such directions are not a legislative instrument, but are expressed to have

effect, and must be complied with, despite any other Commonwealth law.[110]

Proposed section 140ZQ provides that proposed

Division 3B of Part 2 of the Migration Act binds the Crown in right

of the Commonwealth and each of the states and territories. The provision

expressly states that this does not make the Crown liable to be prosecuted for

an offence; however, this does not prevent it from being liable to pay a

pecuniary penalty.[111]

Skilling

Australians Fund Revenue and visa trends

A number of immigration factors will determine future

revenue for the SAF, as revenue will be dependent on the number of visas

granted, and for Temporary Skills Shortage (TSS) visas, how long each visa is

valid.

Permanent

sponsored visas

Government policy has traditionally been the primary

factor determining the number of permanent visas granted each year. According

to the Department of Immigration and Border Protection, the number and

allocation of permanent visas is set by the Australian Government following:

... broad public

consultations with stakeholders, including business and community groups from

all states and territories. Community views, economic and labour force forecasts,

international research, net overseas migration and economic and fiscal

modelling are all taken into account when planning the programme.[112]

SAF revenue raised by visa grants for both permanent

employer sponsored visa categories–the Employer Nomination Scheme (ENS) and the

Regional Sponsored Migration Scheme (RSMS)–will therefore depend on how many

visas are allocated by future governments.

Since 2014–15, there have been 48,250 visas available each

year in these visa categories.[113]

However this figure includes the sponsored employee and their spouse and/or

children. Using figures provided by the Department of Immigration and Border

Protection, approximately 45.8 per cent of permanent employer sponsored visas

were granted to the primary visa holder, the employee, in 2015–16, equal to

22,110.[114]

This is the relevant figure for revenue projections as only the employee is

subject to the proposed levy. The government does not control how many primary

visa holders will bring spouses and dependent children however it is likely

variations in the number of spouses and children will only marginally affect

the revenue raised.

While the allocation of ENS and RSMS visas has remained

constant for the past three financial years, the government may choose to

increase or decrease this figure in the future. In the past, demand for these

visas from employers and immigrants has outstripped the supply of places

allocated by the government, meaning the government allocation is the number of

visas granted.[115]

For example, as at 30 June 2017 there were 52,082 applications waiting to be

processed by the Department of Immigration and Border Protection, more than the

allocation for 2017-18.[116]

However there is a possibility recent policy change may

see the supply of available places outstrip demand from immigrants, as fewer

migrants and employers are able to meet the eligibility criteria. In an August

2017 report discussing recent policy change, Dr Bob Birrell concluded:

It seems very likely that when the reset is in full operation

from March 2018, the number of permanent entry employer sponsorship visas will

drop to a third or less of the current annual number of around 48,000

(principal applicants and dependents).[117]

Birrell nominates the reduction in eligible occupations

for the ENS and RSMS visa, as well as the proposed work experience requirement.

A two-thirds reduction in the number of permanent employer sponsored visas

would substantially reduce incoming revenue for the SAF over the forward

estimates.

Temporary

sponsored visas

Compared to permanent sponsored visas, there are a larger

number of factors determining revenue for temporary sponsored visas. Government

policy can play a role, such as by limiting or expanding the number of eligible

occupations and the level of the salary threshold used. However in addition to

policy decisions, economic factors are important, such as the demand for labour

from employers. This can produce substantial variation in the number of visas

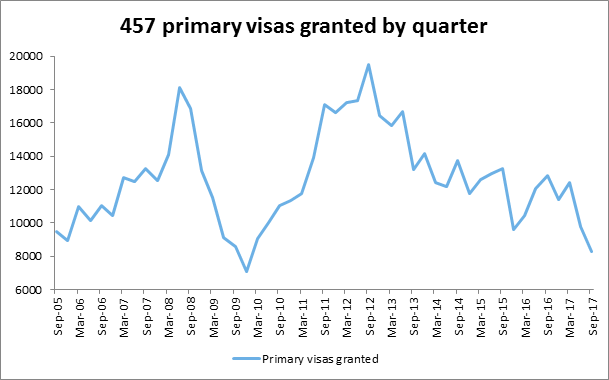

granted over time as demonstrated in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3: primary

457 visas granted each quarter 2005–2017

Source: Parliamentary Library based on Australian Government, Temporary Work

(Skilled) visa (subclass 457) Programme, data.gov.au, BP0014 Temporary Work

(skilled) visas granted 30 September 2017.

Demand for temporary migrant workers slowed in the

aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis, before rising with the post-GFC

mining boom. More recently, tighter policy settings and labour market slack

have reduced the number of visa grants. For example, the July–September 2017

quarter is down 37 per cent compared to the same quarter in 2016.

Unlike permanent sponsored visas, the price of the levy

for temporary sponsored visas will depend on the length of time the visa is

valid. Currently, 457 visas are valid for either up to two years or up to four

years, depending on what occupation is nominated. The Department of Immigration

and Border Protection does not provide information on how long visas are

granted for, noting four years is the maximum time period for one visa grant.

The Azarias review documented the length of time for 457 visas granted

between August 1996 and May 2010:

- 6

months or less: 15 per cent

- 6–12

months: 16 per cent

- 1–2

years: 27 per cent

- 2–3

years: 21 per cent

- 3–4

years: 16 per cent

- 4

years and longer: 5 per cent.[118]

Both the number of temporary sponsored skilled visas and

their validity length may change in response to both government policy and

economic conditions. Forecasting this change is difficult, as future demand

from employers and immigrants may not be reflected in historical trends.

Taken together, SAF revenue will shift over time in

response to both changes in permanent and temporary skilled sponsored visa

grants. These shifts will be difficult to forecast, particularly if the demand

for permanent sponsored visas fails to meet the allocated supply.

Labour Market Testing requirements

Background

Labour Market Testing (LMT) is the process of advertising

a job to recruit Australian citizens and permanent residents. Since the

introduction of the 457 visa program in 1996, LMT has been a prominent point of

contention. However, recent changes announced in April 2017 signal bipartisan

support for LMT as a precondition for any temporary sponsored visa, noting

there are a series of international treaties that give effect to exemptions.

LMT was required on the introduction of the 457 visa in

1996, with a waiver applying if sponsored migrants undertook ‘key activities’.[119]

In July 2001, LMT was abolished and replaced by a minimum skill threshold.[120]

In July 2013, LMT was re-introduced by the Migration Amendment (Temporary

Sponsored Visas) Act 2013.[121]

However in practice, a majority of occupations were exempted from LMT by the

skill level exemption legislative instrument.[122]

Minister Dutton has signalled these skill-based exemptions will be removed from

March 2018, leaving only international treaty obligation exemptions in place.[123]

Existing

provisions

The SAF Bill gives the Minister the power to determine

certain requirements for LMT. Currently, section 140GBA of the Migration Act

provides that certain nominations are subject to a requirement to provide

evidence of LMT unless international trade obligations apply. Where section

140GBA applies to a sponsor (and there is no applicable exemption), LMT must be

undertaken as a condition for approval of a nomination.[124]

Existing subsection 140GBA(5) sets out certain evidence of

LMT which ‘must’, and evidence which ‘may’ be provided in support of a

nomination under section 140GB. It provides that the nomination must be

accompanied by information about the approved sponsor’s attempts to recruit

suitably qualified and experienced Australian citizens or permanent residents

to the position.[125]

Further details of what should be included in this are set out in existing

subsection 140GBA(6).

Additional evidence may also be provided, including

recent research relating to labour market trends (generally and in relation to

the nominated occupation), expressions of support from Commonwealth, state and territory

government authorities with responsibility for employment matters, and any

other type of evidence determined by the Minister by legislative instrument.[126]

Proposed

amendments

The SAF Bill repeals subsections 140GBA(5),(6) and (6A), and

substitutes them with proposed subsections 140GBA(5) to (6C).[127]

The main effect of the amendments is to:

- remove

from the Migration Act all particulars of the evidence that must (and

may) be provided in relation to LMT and

- give

the Minister the power to determine both the manner in which LMT must be

undertaken and the kinds of evidence of LMT which should accompany a

nomination.

Proposed subsection 140GBA(5) states that the

Minister may, by legislative instrument, determine the manner in which LMT in

relation to a nominated position must be undertaken.[128]

Proposed subsection 140GBA(6) provides a non-exhaustive list of matters

which the Minister may determine as part of this, including the language,

method and duration of advertising of the position.

Under proposed subsection 140GBA(6A), the Minister

has the power to make a legislative instrument determining the kinds of

evidence which must accompany a nomination. This may include a copy of any

advertising which has been required in relation to the position.[129]

Proposed subsection 140GBA(6C) states that in

either of these legislative instruments, the Minister may prescribe different

manners of undertaking LMT, or different evidence to be provided, for different

nominated positions or classes of nominated positions. A legislative instrument

made under either proposed subsection 140GBA(5) or (6A) will not be

disallowable.[130]

In his second reading speech for the Bills, Minister

Dutton stated that the amendments will ensure a uniform approach to LMT from

employers, and that the quality of the LMT being conducted is properly

assessed.[131]

The Law Council expressed support for the proposed

amendments to the LMT requirements, noting that the types of evidence of LMT

which will be required to accompany the nomination are similar to those

required by other jurisdictions, including New Zealand, the UK and Canada.[132]

The Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) raised concerns that the proposed

provisions give the Minister significant discretion to determine LMT

requirements, arguing:

the extent to which, if at all, such a system will establish

a rigorous LMT process will of course depend on the content of any legislative

instrument/s that the Minister chooses to issue or indeed whether the Minister

elects to issue such instruments at all.[133]

The ACTU suggested that the text of the SAF Bill be

amended to specify that the evidence of LMT required include the number of

Australian citizens and permanent residents who applied for the nominated

position and the reasons why they were considered not suitably qualified or

experienced.[134]

Application

provisions

The amendments in the SAF Bill which relate to the NTC charge

and to the changed LMT requirements will apply in relation to nominations made

on or after the commencement.[135]

The Explanatory Memorandum notes that this will prevent businesses from being

simultaneously required to comply with the existing training benchmarks and pay

the NTC charge. Sponsors will not be required to continue to meet the training

benchmark requirements after commencement.[136]

Amendments relating to who can lodge a nomination

application will apply to all nominations made on or after commencement, as

well as nominations made before commencement but not yet decided.[137]

Concluding comments

The SAF Bill and Charges Bill respond to both skills and

immigration policy trajectories to provide more sustainable and accountable

funding to address skill shortages, particularly those currently served by

Australian Apprenticeships. As Dr Craig Fowler and Dr John Stanwick of the

National Centre for Vocational Education Research have observed ‘[t]he

apprenticeship model is valuable and enduring—and it can be made much more bold

and ambitious.’[138]

However, while the Bills set the specifications for charges

to fund the SAF, outcomes will ultimately rely on implementation arrangements

well outside the scope of these Bills. The value of this more focused investment

in apprenticeships (compared with the former NPASR, which funded structural

change in the VET system overall) depends on a new Partnership Agreement with

state and territory governments, their matched funding and project

specifications, and the revenue from the levy, if projects are to genuinely add

value to existing apprenticeship investment.

As with any forecast, there is an inherent degree of

uncertainty in future immigration trends. This is particularly pertinent in

periods following substantive policy change, including the Turnbull

Government’s April 2017 announced replacement of the 457 visa program, and

changes to associated permanent sponsored visa categories. Revenue collection

for the Skilling Australians Fund generated from the proposed levy will need to

be followed closely over time if cross-jurisdictional agreements between the

Federal Government and the state and territory governments on skills policy

come to wholly rely on this funding source.

Members, Senators and Parliamentary staff can obtain

further information from the Parliamentary Library on (02) 6277 2500.

[1]. SAF

Bill, clause 2. The effect of the Family Violence Bill on the provisions in the

SAF Bill is discussed in more detail in the ‘Key Issues and Provisions’ section

below.

[2]. Charges

Bill, clause 2.

[3]. Australian

Government, ‘Part

2: Payments for Specific Purposes’, Budget measures: budget paper no. 3:

2017–18, p. 35. A copy of the National Partnership Agreement on Skills

Reform (NPASR) and state and territory implementation plans are available from

the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) Council on Federal Financial

Relations (CFFR), ‘National

partnerships - skills and workforce development’, CFFR.

[4]. Australian

Government, ‘Part

2: Payments for Specific Purposes’, Budget measures: budget paper no. 3:

2017–18, p. 34.

[5]. Department

of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C), ‘Performance reporting

dashboard: skills’, PM&C website.

[6]. CFFR,

‘Agreements’,

CFFR website; COAG, National

Partnership Agreement on skills reform, op. cit., p. 10. This is in

addition to Commonwealth own purpose expenses, including VET programs and

funding to students, employers and industry such as Australian Apprenticeships,

VET Student Loans, and the Australian Apprenticeships Incentives Programme.

More information on major funding flows within the VET system is available from

the Productivity Commission, ‘Vocational

education and training’, Report on government services, 2017, pp.

5.4–5.6.

[7]. CFFR,

‘National

partnerships - skills and workforce development’, op. cit. A large volume

of research addresses the quality and financial sustainability concerns that

accompanied the expansion of VET FEE-HELP, which was associated with the

quality concerns raised in the ACIL Allen Consulting Review of the National Partnership Agreement on skills reform,

report to the Commonwealth and States and Territories, 21 December 2015.

Although many of these issues were outside the scope of the NPASR, they had a

significant impact on the higher-level objectives it was intended to contribute

to. The details of the VET FEE‑HELP controversy are discussed in more

detail on pages 10–15 of J Griffiths, VET

Student Loans Bill 2016 [and] VET Student Loans (Charges) Bill 2016 [and] VET

Student Loans (Consequential Amendments and Transitional Provisions) Bill 2016,

Bills digest, 41, 2016–17, Parliamentary Library, Canberra, 2016.

[8]. ACIL

Allen Consulting, Review of the National Partnership Agreement on skills reform,

report to the Commonwealth and States and Territories, 21 December 2015; PM&C,

‘Performance reporting

dashboard: skills’, op. cit.

[9]. Ibid.

[10]. The

latest performance reports are for 2016, available from PM&C, ‘Performance reporting

dashboard: skills’, op. cit.

[11]. Australian

Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Education

and Work, Table 26, cat. No. 6227.0, ABS, Canberra. 2017.

[12]. Based

on preliminary data for 2015, PM&C, ‘Performance reporting

dashboard: skills’, op. cit.; Qualification levels under the Australian

Qualifications Framework (AQF) are outlined on the ‘AQF qualifications’

webpage.

[13]. PM&C,

‘Performance reporting

dashboard: skills’, op. cit.

[14]. Department

of Employment, The

Skilled Labour Market: A pictorial overview of trends and shortages, 4

September 2017, slide 4.

[15]. Parliamentary

Library based on National Centre for Vocational Education Research (NCVER), ‘Historical

time series of apprenticeships and traineeships in Australia from 1963 to 2017’,

NCVER website, 7 December 2017, Table 4; Table 6.

[16]. A

full summary of changes is provided at Appendix 3 of the Australian National

Audit Office (ANAO), Administration

of the Australian Apprenticeships Incentives Program: Department of Education

and Training, Audit report, 31, 2014–15, ANAO, Barton, ACT, 2015, p.

91; P Noonan and S Pilcher, Finding

the truth in the apprenticeships debate, Mitchell

Institute report, 03/2017, Mitchell Institute, Melbourne, August 2017.

[17]. Department

of Employment, The

Skilled Labour Market: A pictorial overview of trends and shortages, op.

cit., slide 13.

[18]. M

Ruhs and B Anderson, Migrant Workers: Who Needs Them? A framework for the

analysis of staff shortages, immigration, and public policy, in M Ruhs and B

Anderson, edn, Who Needs Migrant Workers? Labour shortages, immigration and

public policy, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2010, p. 15.

[19]. Ibid.

[20]. N

J Roach, Business

temporary entry: future directions, Report by the Committee of Inquiry

into the Temporary Entry of Business People and Highly Skilled Specialists,

Canberra, 1995, p. 84.

[21]. J

Azarias, J Lambert, P McDonald and K Malyon, Robust

new foundations: a streamlined, transparent and responsive system for the 457

programme : an independent review into the integrity in the Subclass 457

programme, Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP),

Canberra, September 2014, p. 20.

[22]. Ibid.

[23]. The

28 occupations listed by the Department of Employment as areas of major skill

shortage are based on assessment of around 80 large skilled occupations defined

in the Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations

(ANZSCO), and assessed occupations are subject to change annually. For more

information see Department of Employment (Employment), ‘Skill

shortage research methodology’, Employment website, last modified 31 August

2017.

[24]. P

Dutton (Minister for Immigration and Border Protection), Migration (IMMI

18/004: Specification of Occupations—Subclass 457 Visa) Instrument 2018.

[25]. DIBP,

‘Fact sheet one:

reforms to Australia's temporary employer sponsored skilled migration programme

- abolition and replacement of the 457 visa’, April 2017 (updated May

2017). The requirement that employers nominating a worker for a Temporary

Skills Shortage visa pay a contribution to the SAF was also included in the

announced reforms.

[26]. M

Turnbull (Prime Minister) and P Dutton (Minister for Immigration and Border

Protection), Putting

Australian workers first, media release, 18 April 2017.

[27]. Migration Regulations

1994, section 2.79.

[28]. C

Evans (Minister for Immigration and Citizenship), Government

announces changes to 457 visa program, media release, 1 April 2009.

[29]. P

Dutton (Minister for Immigration and Border Protection), Migration (IMMI

17/045: Specification of Training Benchmarks and Training Requirements)

Instrument 2017.

[30]. J

Philips and H Spinks, Skilled

migration: temporary and permanent flows to Australia, Background note,

Parliamentary Library, Canberra, 6 December 2012, p. 12.

[31]. P

Dutton (Minister for Immigration and Border Protection), ‘Second

reading speech: Migration Amendment (Skilling Australians Fund) Bill 2017’,

House of Representatives, Debates, 18 October 2017, p. 11031.

[32]. J

Azarias, J Lambert, P McDonald and K Malyon, Robust

new foundations, op. cit., p. 12.

[33]. S

Birmingham, ‘Interview

with Simon Birmingham’,

Breakfast with Aaron Stevens, 4RO, 31 October 2017.

[34]. Department

of Education and Training (DET), ‘Skilling

Australians Fund’, DET website, pp. 1–2.

[35]. S

Birmingham, ‘Answer

to Question without notice: Employment’, [Questioner: D Fawcett], Senate, Debates,

10 May 2017, p. 3273.

[36]. Commonwealth

funding includes support through the Australian Apprenticeship Support Network,

the Australian Apprenticeships Incentives Program, and Trade Support Loans. The

full range of support is outlined on the Department of Education and Training, Australian Apprenticeships

website. See also: Australian Government, Portfolio

budget statements 2017–18: budget related paper no. 1.5: Education and Training

Portfolio, Program 2.8: Building Skills and Capability.

[37]. Australian

Government, Budget

measures: budget paper no. 2: 2017–18, p. 89.

[38]. Australian

Government, ‘Part

2: Payments for Specific Purposes’, op. cit., p. 5. While this wording appears

to suggest Fund revenue may be managed through a Special Account, the Bills do

not provide information on how the SAF will be created or administered. According

to the Department of Finance (DoF), ‘Special

appropriations: special accounts’, DoF website, ‘A special

account is a limited special appropriation that notionally sets aside an amount

that can be expended for listed purposes. The amount of appropriation that may

be drawn from the CRF by means of a special account is limited to the balance

of each special account at any given time.’ Under section 78 of the Public Governance,

Performance and Accountability Act 2013, Special Accounts may be

created by determination.

[39]. ACIL Allen Consulting, Review of the National Partnership Agreement on Skills Reform: final

report, op. cit., p.

xiii.

[40]. Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills, Scrutiny

digest, 13, 2017, The Senate, Canberra, 15 November 2017, p. 35.

[41]. Ibid.,

p. 34.

[42]. Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills, Scrutiny

digest, 15, 2017, The Senate, Canberra, 6 December 2017, p. 75.

[43]. D

Cameron (Shadow Minister for Skills, TAFE and Apprenticeships), Turnbull

Government all at sea on skills and apprentices as funding remains in limbo,

media release, 27 September 2017.

[44]. D

Cameron (Shadow Minister for Skills, TAFE and Apprenticeships), National

Apprentice Employment Conference: Group training: apprenticeships for

prosperity Sydney, speech, 3

November 2017, p. 8.

[45]. TAFE

Directors Australia (TDA), ‘Federal budget

unveils a new model of skills funding’, TDA Newsletter, 15 May 2017;

Australian Council for Private Education and Training (ACPET), ACPET

welcomes new and stronger $1.5 billion skills fund, media release, 10

May 2017.

[46]. National

Apprentice Employment Network (NAEN), ‘Federal

budget gives a much needed lift to apprentices and trainees’, media

release, 10 May 2017.

[47]. TAFE

Directors Australia (TDA), Submission

to Senate Standing Committee on Education and Employment, Inquiry into the

Migration Amendment (Skilling Australians Fund) Bill 2017, and the Migration

(Skilling Australians Fund) Charges Bill 2017 [provisions], 15 December 2017,

pp. 1–2.

[48]. NEAN,

Submission

to Senate Standing Committee on Education and Employment, Inquiry into the

Migration Amendment (Skilling Australians Fund) Bill 2017, and the Migration