88 Leave of the Senate

-

A motion otherwise requiring notice may be moved without notice by leave of the Senate.

-

Leave of the Senate is granted when no senator present objects to the moving of the motion or other course of action for which leave is sought.

Amendment history

Adopted: 19 August 1903 as SO 128 (corresponding to paragraph (2))

1989 revision: Old SO 135 renumbered as SO 88 and paragraph (1) added for removal of doubt; language simplified and clarified

Commentary

Senator William Higgs (ALP, Qld) who thought that the power given to a single senator to deny leave was too great (Source: National Library of Australia)

It is frequently observed that anything may be done by leave and a great deal of business is facilitated by the routine granting of leave, with or without conditions. An example of a motion routinely moved by leave is a motion to vary the membership of committees, which would otherwise require notice. A list of proposed membership changes is circulated in the chamber in advance and the ability of the Senate to act quickly, by leave, to make necessary changes ensures that committees are able to continue their business in the most efficient way possible. A senator who wishes to incorporate material in Hansard is usually granted leave to do so on the condition that the material has been shown in advance to the party whips who are able to ascertain that the material does not contain anything of an unparliamentary character.

Paragraph (1) was added in the 1989 revision, probably to remove any doubt about the ability to move, by leave, a motion that would otherwise require notice. A school of thought had held that it was necessary to suspend standing orders to move such a motion without notice. Although the question was largely settled in 1904 (see SO 79), doubt surfaced from time to time until put to rest by the revision.

The view that anything not expressly permitted is forbidden is a view that runs counter to a view of standing orders as rules to facilitate the orderly conduct of business in the Senate without transgressing the rights of individual senators to participate on an equal footing, subject to any agreed limitations. The latter view has been the dominant view in the development of the Senate’s procedures. That the risks may be overstated is evident in Edwards’ notes on this standing order in the 1938 MS:

It is an axiom of parliamentary procedure that almost anything can be done by leave of the House. During rush periods at the end of a Session it frequently happens that an entire Bill in committee is, by leave, taken as a whole and agreed to. This is quite contrary to the purpose behind many of the Standing Orders, and has in it an element of danger. It might even happen that a very small Senate (which might be less than a quorum) could agree, by leave, to pass something which a majority of Senators, who at the time were not present, would be opposed to. The only safeguard against a happening of this kind would be the sense of duty on the part of Senators to see that they were present to prevent such a happening.

In these days of live broadcasts of proceedings, whips on duty at all times and the certainty that any irregularities in the granting or use of leave will be paid for, leave is a useful and carefully monitored device to facilitate proceedings.[1]

The Procedure Committee's First Report of 2008 which recommended that the Senate adopt the practice of granting leave for 'short' statements, times to one or two minutes as the occasion required

It has always been the case that a record of significant occasions where leave has been denied is kept in the Journals (and indexed accordingly). No attempt is made to record all occasions where leave is granted or denied, but a record is kept of occasions where the standing orders require leave to be sought or where action taken is clearly outside what the standing orders authorise, including the following:

-

bills taken as a whole in committee of the whole;

-

motions moved by leave rather than on notice;

-

amendments moved in circumstances not permitted by the standing orders, such as an amendment to a formal motion or urgency motion, or multiple amendments moved together to bills;

-

tabling of documents by senators other than ministers;

-

making of statements;

-

personal explanations under standing order 190;

-

motions to postpone matters moved by senators other than ministers;

-

recording of votes by groups of senators when a division is not called;

-

senators amending their own motions after having moved them;

-

notices of motion given outside the designated times;

-

presentation of reports of the Selection of Bills Committee at other than the designated time.

In these cases, the words “by leave” are included in the Journals entry.

It is usual for a senator seeking leave to explain briefly the purpose for which leave is sought. Leave may be denied by one senator. When the standing order was adopted in 1903, Senator Higgs (ALP, Qld) thought that the power given to one senator to deny leave was too great and could be misused “because he happens to be in a bad temper or has an impaired digestion”. He floated an alternative, “to the effect that the majority of the senators present, or at least two-thirds of those present, [should] have power to give leave”. Both President Baker and the Chairman of Committees, Senator Best, combined forces to dissuade him:

Senator Sir RICHARD BAKER (South Australia). – Senator Higgs has overlooked the fact, that when leave is asked for, it is for something which as a rule is contrary to the standing orders. We make standing orders in order that the public business may be properly regulated, and leave to do something which is not in accordance with the standing orders ought to be unanimously given, or otherwise we shall get into difficulties.

Senator Best drew attention to the impracticality of the two-thirds rule, reminding the Senate that standing orders could be suspended by an absolute majority (then 19 senators). Either leave was unanimous, in accordance with universal parliamentary practice, or other procedures should be relied upon.[2]

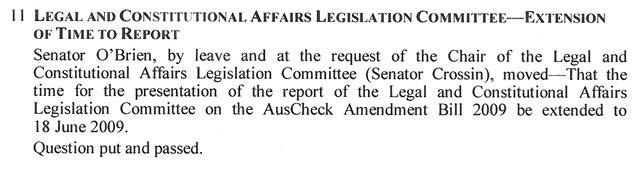

An extract from the Journals of the Senate showing an example of business transacted by leave

In 2008, the Procedure Committee considered the practice of making statements by leave in the context of concern expressed by senators that consent by the Senate for a senator to make a short statement could not be enforced. Rather than recommending any changes to standing orders, the committee suggested that senators either seeking or granting leave could do so for a fixed time limit (of, say, 2 minutes) and the clock could be set accordingly.[3]

See Odgers’ Australian Senate Practice, 12th edition, pp.166–67 for further analysis of leave.