CHAPTER 4

A way forward

4.1

Absent from the Government’s package is any provision of independent

advice resulting from a considered processes involving consultation, evaluation

and analysis. Instead, fee deregulation has been presented as the one and only

'quick fix' solution to a sustainable higher education sector in Australia.

4.2

The Australian higher education sector is not at a tipping point – and

yet, the combination of the Abbott government's budget cuts and the provisions

of this package represent real threats to participation, attainment and the quality

of our current successful system. In the words of Professor Stephen Parker, Vice-Chancellor

of the University of Canberra:

We should not be taking risks with this. In the absence of

evidence, modelling and time for consultation, we should be taking this

carefully. The stakes are very high.[1]

4.3

Fee deregulation places at risk the achievements of previous governments,

including increased resourcing per student place, increased indigenous and

regional student participation, and increases in overall investment in

universities.

4.4

The Government’s package was unexpected. Both the Australian public and

the higher education sector would be better served by a proper, well-informed

debate and a reform process based on clearly articulated goals and how they

will serve the public interest.[2]

Moreover, it is imperative that all Australians have a clear understanding of the

arguments for and against any proposed changes to the higher education system and

the mechanisms by which such changes will be achieved.

False and misleading advertising – a waste of taxpayer dollars

4.5

On 7 December 2014, the Abbott government launched a taxpayer-funded

advertising campaign designed to address supposed misunderstandings about

higher education funding and the changes contained in the HERR bill (and its

defeated predecessor, the HERRA bill). The $14.6 million campaign spans

television, radio, newspaper, digital media, social media and bus shelters.[3]

The purpose-built campaign website features video, infographics and a true or

false quiz.[4]

4.6

The Short-term Interim Guidelines on Information and Advertising

Campaigns by Australian Government Departments and Agencies (June 2014) (the

Guidelines), which were in effect when the Secretary of the Department of

Education certified the campaign as compliant, stipulate that all advertising

campaign materials should be presented in an objective, fair and accessible

manner.[5]

The Guidelines specify that:

[w]here information is presented as a fact, it must be

accurate and verifiable. When making a factual comparison, the material should

not attempt to mislead the recipient about the situation with which the

comparison is made and it should state explicitly the basis for the comparison.[6]

4.7

The Government's advertising campaign presents misleading, unverifiable

figures as fact and offers no information about the basis of its calculations.

Policy experts have questioned the accuracy of the Government's claims, with

Andrew Norton noting that regardless of their veracity, the figures used are

'not particularly meaningful in the first place'.[7]

4.8

The Guidelines require that advertising campaigns be 'instigated on the

basis of a demonstrated need'.[8]

While there has been some attempt to use unverifiable anecdotes and third-party

market research to justify the campaign,[9]

there is no demonstrated need for a wide-scale, multimillion dollar advertising

campaign to promote a bill that has not yet passed the Parliament.

4.9

The campaign does not address the bill's core policy objectives, instead

offering misleading and meaningless assurances to prospective students and the

broader public. It is clear the campaign has been developed not to address

demonstrated need but rather in response to the negative reaction to the

Government's proposed changes from students, education providers and the

Australian public. The campaign's clear political purpose itself breaches the

Guidelines, which require that '[c]ampaign materials must not try to foster a

positive impression of a particular political party or promote party political

interests.'[10]

The current system works

4.10

The committee received overwhelming evidence that the current higher

education system is sustainable and high quality. For example, Mr Ben Phillips

and Professor Parker argue that:

[A]t the moment student contributions are already quite high

in Australia from an OECD perspective. The Australian university system appears

to be working very well: we have 19 universities in the top 500 and on a per

capita basis we are ranked fourth in the world. We are very attractive for

international students, and the international market is very healthy here in

Australia. I guess we are not quite sure what is the problem... That is something

that needs to be explained.[11]

4.11

The Council of Australian Postgraduate Associations (CAPA) also posited

that the current system is workable and would ultimately produce better future

outcomes for the Australian higher education sector.

[D]espite the current system's flaws in terms of the funding

gaps particularly around cases that were involved with the research training

scheme, the changes proposed in the bill before the Senate would only

exacerbate funding gaps in the system and are more likely to cause harm to the

sector over the long term than the current arrangements that the sector is

working within. It is our view that solutions can be found within the current

arrangements that will address gaps in funding, participation and equity issues

and will be far more effective than those currently being proposed by the

government.[12]

4.12

Australia Needs a Brighter Future agreed with the notion that the

current arrangements for the funding of the higher education sector are preferable

to those proposed in the package.

[T]he current funding models are far superior to the proposed

funding models the government has put up. I think the viability of the

government's proposed funding models needs to be contextualised with what is

actually going to happen as result of the government's funding model. It is

important to look at how this will affect students and how it will affect

future students. I do not think the government's proposed model will affect

them in a way that is better than the current structure.[13]

Fee deregulation is unnecessary

4.13

Education policy analyst Professor Louise Watson argued that evidence

obtained in the Higher Education Base Funding Review chaired by Jane

Lomax-Smith, which reported in October 2011, led to the conclusion that

Australian universities were doing very well.[14]

In discussing the fee deregulation proposal, Professor Watson argued that it

was a further impost on the Commonwealth budget and that it would be more unpredictable

than the removal of caps on funded places.[15]

I have always been puzzled as to why fee deregulation was

necessary or deemed necessary. I have never understood the problem it was meant

to fix. From where I stand, it seems like fee deregulation will simply compound

the problems currently facing the government in terms of university financing,

not solve them.[16]

4.14

The National Union of Students (NUS) contended that fee deregulation

would result in decreased opportunities and accessibility and equity for students

and provided evidence before the committee that deregulation, as proposed, will

be unpredictable and unsustainable.

We have not seen enough evidence that this is a good funding

model for universities as well. We do believe that universities have been

underfunded for quite a while. However, as per the Bradley review, there should

be higher funding into universities. The funding model that we have currently

will not stratify universities into such a two-tiered extent that deregulation

would see.[17]

4.15

The National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU) noted that 'nobody,

including the government, seems clear as to the rationale or underlying

principles of the proposed policy framework'.[18]

If anything, the

Government's proposals are based on inaccurate, inadequate assumptions about

public funding, student debt and the role of higher education in Australia.

4.16

Blanket

deregulation is a lazy solution to a complex problem; as Andrew Norton

acknowledged, '[f]ee deregulation saves a regulator from the complex task of

determining reasonable costs.'[19]

The opportunity for genuine, long-term reform has been discarded in what

Innovative Research Universities described as a 'shortsighted search for

savings'.[20]

4.17

Submissions

and public comments have exposed that the government’s higher education package

does not enjoy broad-based support. Along with students and staff opinion

against the package, every university submission calls for changes, or delay,

or a new process to be undertaken.

Debt but no degree

4.18

Some time was spent at the public hearings examining issues

around attrition, and non-completion of degrees. Mr Andrew Norton, of the

Grattan Institute explained the attrition rate:

The government gives two attrition rates, one is is the

student enrolled at the same institution the following year, and then there is

the adjusted one, which is are they enrolled anywhere at all in the system. We

usually go with the 'anywhere at all in the system' as the more accurate

figure. That has been trending up a little bit. How this works out in the final

completions is very hard to say because people do take leave from their course

and then go back later on, so simply the fact that they are not anywhere in the

system the year after they started does not mean they will never come back—but

obviously it is a bit of a negative sign.

4.19

The Committee heard from Professor Louise Watson on the concerns

the 2011 Base Funding Review had about retention:

The base-funding review was concerned about retention and

efficiency, even in 2011. It was obvious to us that with the size of the

expansion and the lowering of ATARs that higher attrition was likely to occur,

which was inefficient for the system and a very bad outcome for the students.

We recommended in the base-funding report that performance incentives related

to student completions should be included in the compact negotiations with

higher education institutions. Basically, it should take into account where

students have undertaken their degrees—students do move between universities,

so it would not be fair for the university where they complete their degree to

receive that sort of bonus. We thought it should be included in the compact

negotiations as a performance target and as an incentive for universities to

focus on supporting students through to graduation.

4.20

In evidence before the committee, Jeannie Rae, National President

of the NTEU also expressed similar concerns:

I think that it is a fundamental advance that more students

have enrolled at university, and clearly from more broader backgrounds. What concerns

me greatly is the issues that we are now seeing with attrition and progression.

What happens to them when they are in the university is fundamentally important

and what it is all about.

4.21

Mr David

Phillips suggested that there was some evidence of changes in higher education

provider behaviour:

There is some evidence arising, I think, that institutions

have very rapidly increased their intake of students at the lower ATAR bands—if

we are just looking at year 12 applicants. We know that low-ATAR-entry students

do not complete their courses at the rates of students with higher levels of

ATAR, so it is an important issue. But it is very important to stress that

ATARs are only one measure of entry criteria, and any policy change to the

demand-driven system would need to be reasonably sophisticated to take into

account all of the different types of entry criteria.

4.22

There is some evidence that universities are offering places to

academically low achieving students. In The Australian on 15 January 2015 Julie

Hare wrote:

TWO out of every five students with a tertiary admission rank

of 50 or lower who applied for university last year were offered a place, a

figure that has quadrupled since 2009, when the figure was one in 10.[21]

4.23

It has been noted by many commentators, including the Teacher

Education Ministerial Advisory Group (TEMAG) that judging admissions through

ATARs is a fraught process. Indeed for many universities admission standards

are distorted by what Professor Warren Bebbington has described as an “out-of-control

bonus points system”. Julie Hare and Kylar Loussikian have written that:

Concerned with perceptions of prestige, universities

artificially inflate their ATAR cut-offs, then allow students to “top-up”

inadequate scores with bonus points for anything from going to a certain

school, living in a certain postcode and taking a certain subject, to being an

elite athlete.

Bebbington says the system, originally developed to address

genuine disadvantage, is so rampant that four in five students in South Australia

get into their preferred course on the basis of bonus points, not their ATAR.

And most students, teachers, careers advisers and parents have no idea how to

work out what is going on.[22]

4.24

The article

further reveals that bonuses of up to 25 points are not unheard of, though

bonuses of 10 to 15 points are more common.

4.25

A google

search of “low ATAR score” reveals a range of advice about how a student can

game systems used by universities to boost their ATAR score and the chance of

an offer to a course.

4.26

Many

universities and commentators readily acknowledge the lack of transparency of

the ATAR system, as more and more students are admitted through direct entry

programs. According to Professor Parfitt of the University of Newcastle:

Many of our students, as I said, do not come to us straight

from school. They do not actually come in with the traditional ATAR. They come

through pathways, whether it is through TAFE or through our enabling programs.

4.27

The TEMAG

report, Action Now: Classroom Ready Teachers addresses this issue of

entry standards extensively:

...trends in ATAR cut-offs are difficult to assess. Providers

may publish notional cut-offs but then admit large numbers of applicants

through such techniques as ‘forced offers’ to individual candidates who do not

possess the required ATAR. In this way, providers can publish unrealistic

cut-offs that are met by relatively few applicants and compare favourably with

the cut-offs published by providers who genuinely report the typical lowest

entry score for their initial teacher education programs.

A further complication is the practice of awarding bonus

points, which can boost an applicant’s ATAR to meet the cut-off for entry. Awarding

of bonus points is a longstanding practice and, in the case of bonus points for

studying subjects such as mathematics, science and languages, one that is

generally supported. Other bonuses may relate to disadvantage, place of

residence or other factors. Some bonuses are applied directly by the provider

while others are applied by a state-based tertiary admission centre. The use of

bonus points may not be inherently problematic, but lack of transparency in

their use adds to the confusion about entry standards for initial teacher

education.[23]

4.28

TEMAG

recommended that:

Higher education providers publish all information necessary

to ensure transparent and justifiable selection processes for entry into

initial teacher education programs, including details of Australian Tertiary

Admission Rank bonus schemes, forced offers and number of offers below any

published cut-off.[24]

It is an observation and finding that could easily be

applied to other fields of education.

Committee view

4.29

The committee is of the view that evidence of emerging trends of a slide

in retention, and the lack of transparency in admissions is of concern. The

committee does not accept the argument that Australia needs to choose between

quality and standards on one hand, and access and equity on the other.

Complex changes should not be based on flawed policy

4.30

A number of submitters to the inquiry emphasised the need for stability

in policy settings for universities and students and suggested a longer

timeframe for changes to higher education that are as large as those contained

in the package.[25]

Dr Gwilym Croucher, a higher education policy analyst and researcher, stated:

Predictability for universities in the rules that they face

and the policy settings allows them to plan better and, ultimately, deliver

better quality education for students and for students to benefit. In any

change that happens to higher education—be it the government's current package

or a modified version of that—it is important that the changes are carefully

considered to ensure stability.[26]

4.31

In this context, Dr Croucher emphasised the need for the government to

be explicit about why it is bringing in the package:

History has shown... that anything that adds complexity to the

system can cause unintended consequences and therefore needs a lot of time to

be analysed before it is brought in, if we are to get optimal outcomes. The

government's current package has had nearly 10 months of scrutiny, and if we go

further back, the reforms undertaken by Minister John Dawkins had a green and

white paper process which set up the current system.[27]

4.32

Even Andrew Norton, on whose work the government is basing its inflated

claims of a $1 million lifetime salary premium for graduates, argued that:

Due to its interaction with the HELP loan scheme, fee

deregulation can create significant additional costs. There are also reasonable

concerns that some universities will increase their fees in ways that do not

benefit students. We need a mechanism that limits these downsides of fee

deregulation while still improving on the pricing system we have today.[28]

4.33

While it is true that there have been a number of reviews into the

Australian higher education system, it is not the case that fee deregulation

has been seriously considered. The Kemp-Norton Review of the Demand Driven

System noted it was unable to consider calls for fee deregulation as they were

outside its terms of reference.[29]

4.34

A comprehensive, systematic review of higher education funding occurred

in 2011 through the Base Funding Review chaired by Professor Jane Lomax-Smith.

This review found that the Australian higher education system is

internationally competitive in terms of quality and funding on available

indicators. It recommended a modest increase in funding per place, a two per

cent increase to meet the cost of learning with new technology, addressing

underfunding in specific disciplines, reducing the number of funding clusters,

adjusting public and private contributions and retaining low-SES student

loading of $1,000 per student.

4.35

Professor John Quiggin of the University of Queensland, in a submission

to a previous inquiry has made the point that:

The current university funding situation is unsatisfactory

and inadequate, but is not at a ‘tipping point’ in which radical reform is

necessary to stave off collapse. In the short term, restoration of the funding

policy prior to the 2013 cuts would be sufficient to stabilize the financial

position of the university sector as a whole.[30]

Committee View

4.36

The committee is of the view that there is a case to update the 2011

Base Funding Review in light of the recent growth in student numbers. As

Professor Watson noted:

... there have been budgetary pressures created by lifting the

cap on student places on the recommendation of the Bradley review. The size of

the sector increased enormously and unexpectedly after that policy reform—a 35

per cent increase in commencing students and a 25 per cent increase in total

student load over five years.[31]

4.37

Any such review should include broad, meaningful stakeholder engagements

to rectify what CAPA described as a 'complete lack of consultation with

stakeholders' up to this point.[32]

4.38

It is also important that independent, expert advice be a continuing

feature of any package. Even Universities Australia, while supporting fee

deregulation, recommended the establishment of an independent advisory panel to

assist the Government with implementation and oversight of deregulation.[33]

The Regional Universities Network similarly supported an oversight committee.[34]

Alternatives to deregulation

4.39

Fee deregulation is not the only option for the Australian higher

education system. There are other ideas worthy of consideration – yet the

Abbott government has failed to pursue any of them.

4.40

Some of the options presented include:

-

Maintaining the current system with some updates to reflect the

fiscal situation and expansion of the sector;

-

Maintaining the current system with increased government funding;

-

Maintaining the current system with increased student

contributions;

-

Fee deregulation with loan limits;

-

Fee deregulation with incremental increases in scholarship

contribution; and

-

Fee deregulation with the Chapman-Phillips model of fines or

levies.

4.41

The committee focussed its attention on the incremental increase in

scholarship contribution alternative put forward by the University of

Wollongong and the Chapman-Phillips model.

Incremental increase in scholarship contribution

4.42

The University of Wollongong proposes a progressive alternative to the

flat 20 per cent scholarship fund contribution. Under this model, an initial 10

per cent contribution would apply to annual tuition fees over $10 000. An

additional

10 per cent increment would apply to every $1 000 up to $15 000, and a further

five per cent would apply to every $1 000 thereafter, reaching a maximum of an

80 percent contribution for tuition fees in excess of $20 000.[35]

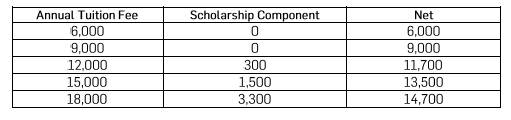

The table sets out the model's effect on the Commonwealth

Scholarship Fund and the net resources available to a higher education

provider.

Figure 2: The effect of the incremental increase in

scholarship contribution model on the Commonwealth Scholarship Fund and net

resources[36]

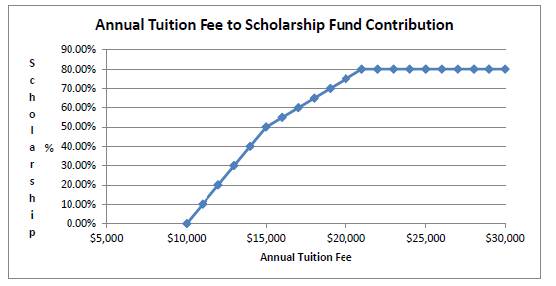

4.43

The graph below illustrates the incremental difference in Commonwealth

Scholarship Fund Contribution in relation to annual tuition fees under the

incremental increase in scholarship contribution model.

Figure 3: Annual tuition fee to Commonwealth Scholarship

Fund contribution[37]

4.44

The University of Wollongong argues that this model retains the key

aspects of the Government's changes in a fairer, more moderated format.[38]

The Chapman-Phillips model

4.45

Professor Bruce Chapman and Mr David Phillips presented an alternative

approach to fee deregulation in the Australian higher education sector. Crucial

to the Chapman-Phillips deregulation proposal is the government's ability to

'withhold and/or reduce subsidies to citizens and institutions if their

situations or behaviour warrant diminished support.'[39]

We need to have mechanisms which maintain the capacity of

price discretion but penalise institutions—that is, have some kind of cost if

they are too high.[40]

4.46

Mr Phillips explained to the committee that the Chapman-Phillips model

was developed to allow the government to reduce or remove the 20 per cent

cut in funding for Commonwealth supported places. Mr Phillips explained that:

savings to the budget would be achieved in proportion, as it

were, or in relation to the extent to which fees are increased. That would

reduce or remove the requirement for universities to increase fees just to

maintain their current revenue levels. If you set the thresholds at which the

reduction in funding would cut in at something like the current maximum student

contribution rates, then it would mean that if an institution chose not to

increase its fees it would not be affected by the policy change.[41]

4.47

The Chapman-Phillips proposal received considerable comment throughout

this inquiry, with some commentators likening it to a big new student tax, or a

fine, or a levy.

4.48

The Innovative Research Universities (IRU) suggested that the

Chapman-Phillips model be explored as an alternative proposal to fee

deregulation. IRU described it as a model that would amend the government's

formula to fund universities taking account of the revenue universities

generate from students:

the more they choose to generate revenue from students, the

less need there is to invest government funding in those universities, and that

is what their schema will do. And it starts from the current funding. There is

actually a significant difference between the current system and the proposal

of the government, which would reduce funding up-front by 20 per cent. It

starts back at the basis of the current funding and then says that as and when

universities go beyond that is when government will start to pull back its

funds.[42]

4.49

IRU noted that exploring this option is very complicated:

there are numerous, innumerable and probably infinite ways

you could do it. You can work through those and make some decisions if you want

to pursue that, but that will take some time.[43]

4.50

Professor John Dewar explained further that from IRU's perspective,

despite the potential complexities of the Chapman-Phillips model, it was worthy

of further research because it appears to address the three key criteria for a

solution to Australia's higher education funding issue:

-

sustainability of government support;

-

sustainability of funding to universities; and

-

affordability for students.[44]

4.51

A number of experts in the higher education field also considered the

Chapman-Phillips model and raised the need for further work to be done to

enable proper judgment on the proposal. Dr Gwilym Croucher made the point that:

Where the different threshold amounts are set will have a

dramatic impact on the incentives provided to institutions and hence on the

behaviour of those institutions and the incentives that are therefore provided

to students in terms of what pricing was being given to students with increased

fees... To assess the proposal, we would need to see significantly more detail to

get some understanding of where it might sit. Without that detail, it is very

hard to make a considered judgement on a proposal such as the one being

suggested.[45]

4.52

La Trobe University also highlighted the need for further information on

the proposal, arguing that the 'devil is in the detail' and that the Chapman-Phillips

proposal was not being suggested as a definitive policy:

We think more work needs to be done to work through the

consequences and the risks and benefits associated with each of those,

including the Phillips Chapman proposal. We would prefer out of all of those

options to weigh them up against a set of principles, which includes benefits to

students and the mitigating risks such as price inflation for students.[46]

4.53

The National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU) produced evidence through a

preliminary analysis of the impact:

The proposal would introduce even more distortions into any

already highly complicated funding regime. Chapman’s is a framework with many

moving parts, all of which interact very differently depending what values are

set for threshold fees at which different marginal tax rates are imposed. Three

examples used in Appendix 1 shows that impact of fee increases with a Chapman

tax varies considerably depending existing rates of public subsidy further

complicating the analysis and understanding of the full implications of the

model.[47]

4.54

The NTEU makes the legitimate point that:

Greater complexity means less transparency and greater

opportunities for gaming and manipulation. The best and most transparent way to

avoid excessive fee increases is to keep a cap on the maximum fee Commonwealth

supported students can be charged.[48]

Rushed radical changes are not in the national interest

4.55

It is clear that there are alternatives to fee deregulation. The higher

education sector and the Australian people would be better served by a detailed

examination of the options available.

These options and the interactions between them and existing

arrangements need to be carefully modelled and assessed in terms of their

consequences – intended and unintended – and potential student and provider

response.[49]

4.56

Policy in the higher education and research sectors is complex and

important, and it is evident that there is need for some reform.

But it does not serve Australia’s interests to rush radical

changes to the sector. Nor does it serve Australia’s interests to cut funding,

create large and unfair debt that will never be repaid, or allow wasteful fee

inflation. The arguments in favour of increasing student debt and creating

deregulated markets for fees are far weaker than the government says. Indeed

the government does not seem to have come to terms with some serious inconsistencies

in its arguments.[50]

4.57

The Abbott government's argument that adequate consultation has been

undertaken for this package, and that the Australian public was warned of the associated

Budget measures, does not stack up – especially when compared to the processes

surrounding radical changes to higher education in the past. In fact, there was

no indication by the Abbott government prior to or even immediately after the

2013 election that it was anticipating the biggest shake-up of the higher

education sector in 30 years.

4.58

The Dawkins reforms in the late 1980s were preceded by extensive

consultation and a formal green and white paper process. The Howard

Government’s 2003–04 Budget decisions on higher education reform were informed

by a review of higher education policy. The Crossroads review held 49 forums in

all capital cities between 13 August and 25 September 2002. Seven issues papers

were published and a total of 728 submissions were received. The process was

also supported by a Productivity Commission research report, University Resourcing:

Australia in an international context, released in December 2002, which compared

11 Australian universities with 26 universities from nine other countries.

4.59

There can be no comparison between the level of consultation on previous

successful attempts at

higher education reform and this attempt, because there has been no

consultation. It was put together as part of a budget process, thus was subject

to the confidentiality that budget processes require. Accordingly the package

can only be viewed as a series of budget savings in search of a rationale. The

development of this package has been characterised by the complete lack of

consultation, research and discussion, exacerbated by the government’s wilful

refusal to release its own limited modelling on the impact of its proposals.

Committee view

4.60

The Abbott government's taxpayer-funded higher education advertising

campaign lacks any discernible merit and is a waste of valuable taxpayer funds.

Not only is it in clear breach of the Advertising Campaigns by Australian

Government Departments and Agencies Guidelines – it has also failed to work. It

is obvious that the substance of the package is at the heart of the problem,

and no amount of spin can make it more attractive to the people of Australia.

The committee notes that fee deregulation remains overwhelmingly unpopular.

4.61

The committee received convincing evidence that Australia's world-leading

higher education system works, has proven successful and is not in need of

immediate change. While the committee acknowledges the system is not perfect,

and continual improvement is always needed, fee deregulation is not the best or

only option.

4.62

In addition to the proposals assessed above, the committee notes that a

variety of alternative policies have been put forward to ameliorate the

negative impacts of fee deregulation, including:

-

putting a limit on how much students can borrow through HECS

(Swinburne University),

-

establishing an independent body to monitor aspects of the

system, including fees and advise the government on possible policy responses

(Universities Australia),[51]

-

allowing the Australian Consumer and Competition Committee (ACCC)

to monitor university fees (Group of Eight), and

-

putting restrictions on how universities are allowed to spend fee

revenue (Peter Noonan, Mitchell Institute).

4.63

Some of these alternative policies, like the Chapman-Phillips student

tax proposal, seem to have been formulated on the premise that ‘why make a

policy straightforward and transparent when there is a complex and obscure

alternative available?’ The committee rejects all of these ideas because their

starting point is fundamentally flawed. Deregulation itself is the problem

these proposals seek to solve. The simple solution is not to embark upon fee

deregulation in the first place.

4.64

The committee believes that rushing radical changes to the higher

education sector is particularly dangerous and contrary to the national

interest. The committee urges the government to consider in detail all the

options available to the higher education sector before implementing any large

scale changes. In embarking on any future reforms to the higher education

sector, the committee suggests the government obtain independent advice,

modelling, evaluation of existing arrangements and technical analysis to

produce a detailed proposal upon which the government can then consult,

negotiate and decide.

Recommendation 3

4.65

The committee recommends that the government commission an independent review

to update the 2011 Base Funding review.

4.66

The committee recommends that further efforts at change to higher

education funding and financing involve proper and due process of research,

consultation and discussion.

Senator Sue Lines

Chair

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page