|

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page

Chapter 2

Overview of serious and organised crime in Australia

Organised crime is a phenomenon that has emerged in different

cultures and countries around the world. Organised crime is ubiquitous; it is

global in scale and not exclusive to certain geographical areas, to singular

ethnic groups, or to particular social systems.[1]

2.1

Perceptions of serious and organised crime frequently consider it

occurring in, or exported from, discrete geographical regions. In reality,

organised crime is widespread and impervious to cultural and geographic

boundaries. Australia is no exception.

2.2

This chapter provides an overview of serious and organised crime in

Australia. It outlines the broad features of organised crime including current

illicit markets, the nature of organised crime groups and the impact of

organised crime on Australian society.

2.3

This chapter also discusses some of the issues associated with

responding to organised crime, including: defining serious and organised crime;

quantifying serious and organised crime; and the trend towards preventing

rather than reacting to serious and organised crime.

2.4

Lastly, during the course of this inquiry, the involvement of outlaw

motorcycle gangs (OMCGs) in organised criminal activity in Australia gained

prominence in the political and public domains. Accordingly, the committee

sought to understand the extent of OMCG organised criminal activity.

Organised crime in Australia: a snapshot

2.5

There is a long history of organised crime in Australia[2]

and, according to Dr Andreas Schloenhardt, an Associate Professor at the

University of Queensland specialising in organised and transnational criminal

law, it is widespread in its reach:

Organised crime can be found across the country and even

regional centres and remote communities are not immune to the activities of

criminal organisations.[3]

2.6

In its current manifestation, organised crime in Australia exhibits a

number of features that largely reflect patterns in organised crime internationally.

Unsurprisingly, an enduring feature of organised crime is that it is primarily motivated

by financial gain.[4]

Further, it generally involves systematic and careful planning, the capacity to

adapt quickly and easily to changing legislative and law enforcement responses

and the capacity to keep pace with, and exploit, new technologies and other

opportunities.[5]

2.7

The Australian Crime Commission (ACC) likens organised criminal 'enterprises'

to conventional businesses in the kinds of measures they adopt to ensure good

business outcomes – risk mitigation strategies, the buy-in of expertise (legal

and financial for example), and remaining abreast of market and regulatory

change. The principal difference is, of course, that their business activities

and profits are illicit.[6]

2.8

The impact of organised crime on Australia is significant. The ACC concluded

that at a conservative estimate organised crime cost Australia $10 billion in

2008. These costs include:

-

Loss of legitimate business revenue;

-

Loss of taxation revenue;

-

Expenditure fighting organised crime through law enforcement and

regulatory means; and

-

Expenditure managing 'social harms' caused through criminal

activity.[7]

2.9

Serious and organised crime not only results in substantial economic

cost to the Australian community but also operates at great social cost. Organised

crime can threaten the integrity of political and other public institutional

systems through the infiltration of these systems and the subsequent corruption

of public officials. This, in turn, undermines public confidence in those

institutions and impedes the delivery of good government services, law

enforcement and justice. Along with this are the emotional, physical and

psychological costs to victims of organised crime, their families and

communities.[8]

Organised crime groups

2.10

Over time a number of criminal organisations have infiltrated or evolved

within Australia – Asian triads, Colombian drug cartels, Italian and Russian

mafia, and OMCGs.[9]

2.11

In the committee's 2007 report on serious and organised crime it was

reported that Asian organised crime groups continued to thrive in Australia

with a broadening of their activities beyond their traditional involvement in

extortion and protection rackets. The presence and expansion of Middle Eastern

organised crime groups was also noted, with drug trafficking, property crime

and vehicle rebirthing reported as their main activities. European crime

syndicates, commonly of Romanian and Serbian origin were reported to be

prominent in WA and to an extent in Queensland and Melbourne.[10]

2.12

The growing involvement of OMCGs in organised crime was further

highlighted in the committee's 2007 report. This is discussed in more detail later

in this chapter.

2.13

Whilst the presence of these identifiable organised crime groups was

reported, the trend towards 'entrepreneurial crime networks' was also emphasised.

The report discussed the shift from communally-based, strongly hierarchical

crime groups that centre on a singular identity – a particular ethnicity for

example – to more flexible, loosely associated networks.[11]

2.14

This trend was emphasised in evidence to this inquiry. For example,

Assistant Commissioner Tim Morris from the AFP informed the committee that:

The groups are more business driven and will enter into quick

and ready partnerships with whoever may be able to do the type of crime

business that they need to do. So the traditional models—and we have seen it in

the past in documents categorising crime groups along strict ethnic lines—are

becoming less and less relevant and are becoming more and more flexible. People

are shifting around very, very quickly and flexibly into the most profitable

crime types they can find.[12]

2.15

Making a related point, Mr Kevin Kitson from the ACC noted that

increasingly, organised crime is moving out of the sphere of a powerful few at

the head of tightly structured and hierarchical groups to entrepreneurial and

relatively transient partnerships:

[W]e probably need to step away from the concept of a grand

puppet-master somehow coordinating this activity nationally. There are

undoubtedly people who, at the flick of a phone switch, can command resources

and attention and support across the country and internationally, but I think

we would characterise it as being much more entrepreneurial, much more

available to anyone who really has the commitment to seek out organised crime

profits rather than necessarily being the domain of a select few.[13]

2.16

At a state level the same pattern was observed. Deputy Commissioner Ian Stewart

from the Queensland Police Service (QPS) informed the committee that:

Whilst at one time an organised crime group membership was

operated possibly on geographic or ethnic lines which reflected a long-term

commitment, such membership or participation has migrated to more fluid and

flexible approaches that may see a temporary union to execute crime within a

thematic context—for example, black market web portals, a cyber based

environment hosted and conducted for the express purpose of bringing criminals

together to facilitate open trading of illegal commodities and services.[14]

2.17

The ACC reported that notwithstanding the increasingly 'diverse' and

'flexible' nature of organised crime groups, 'high-threat organised crime

groups' tend to hold in common a range of characteristics. The ACC identified

the following features:

-

They have transnational connections;

-

They have proven capabilities and involvement in serious crime of

high harm levels including illicit drugs, large scale money laundering and financial

crimes;

-

They have a broader geographical presence and will generally

operate in two or more jurisdictions;

-

They operate in multiple crime markets;

-

They are engaged in financial crimes such as fraud and money

laundering;

-

They intermingle legitimate and criminal enterprises;

-

They are fluid and adaptable, and able to adjust activities to

new opportunities or respond to pressures from law enforcement or competitors;

-

They are able to withstand law enforcement interventions and

rebuild quickly following disruption;

-

They are increasingly using new technologies; and

-

They use specialist advice and professional facilitators.[15]

Transnational crime

2.18

The committee notes, in particular, the increasingly transnational

nature of organised crime, which the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

(UNODC) has described as 'one of the major threats to human security'.[16]

During the course of this inquiry the committee become aware of the scale and

destructive effects of serious and organised crime and transnational crime. Mr

Antonio Maria Costa, Director General of the United Nations Office on Drugs and

Crime (UNODC) outlined his concerns regarding the global crime threat:

I believe we face a crime threat unprecedented in breadth and

depth...drug cartels are spreading violence in Central America, Mexico and the

Caribbean. The whole of West Africa is under attack from narco-traffickers,

that are buying economic assets as well as political power;

collusion between insurgents and criminal groups threatens

the stability of West Asia, the Andes and parts of Africa, fuelling the trade

in smuggled weapons, the plunder of natural resources and piracy;

kidnapping is rife from the Sahel to the Andes, while modern

slavery (human trafficking) has spread throughout the world;

in so many urban centres, in rich as much as in poor

countries, authorities have lost control of the inner cities, to organized

gangs and thugs;

the web has been turned into a weapon of mass destruction,

enabling cyber-crime, while terrorism - including cyber-terrorism - threatens

vital infrastructure and state security.[17]

2.19

Mr Costa reasoned that the global growth of organised crime would be an

ongoing trend, pointing to the current global economic crisis as a trigger for

increased criminal activity.[18]

Organised criminal activity

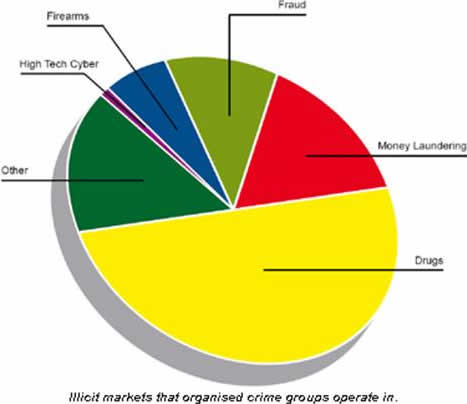

2.20

The ACC's data on organised crime groups in Australia shows that

organised crime groups operate in a range of illicit markets: drugs, money

laundering, fraud, firearms trafficking, high-tech crime, and other activities

(see Chart 1). Each of these is briefly discussed below.

Chart 1 – Illicit markets that Australian

organised crime groups operate in[19]

Drugs

2.21

Illicit drugs are a primary market with significant organised crime

group involvement in the importation, domestic production, and distribution of

these drugs. This includes the production and supply of amphetamines and the

supply of methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, also known as ecstacy), heroin,

cannabis and cocaine.[20]

Mr Kitson from the ACC explained that:

Very few things can give you the same kind of profit margin

that illicit drugs can and the ratio between, if you like, the wholesale or

manufacturing cost and the retail cost is so large that it is likely to remain

for the foreseeable future as the major generator of criminal profit.[21]

Money laundering

2.22

Money laundering comprises a large percentage of organised criminal

activity and is used to conceal the origin of criminal profits. This occurs

through 'the placement of illicit profits into the legitimate economy', which

is achieved by a number of means including:

-

'transfers to financial institutions in countries where Australia

has limited visibility;

-

transfers to other asset types which cannot be easily traced;

-

gambling;

-

the use of money remitters.'[22]

2.23

Increasingly, criminal networks are exploiting technological

opportunities to launder money – for example, through online transfers and

identity fraud.[23]

2.24

Money laundering impacts negatively on the Australian community in a number

of ways. These include: 'crowding out of legitimate businesses in the

market-place by money laundering-front businesses', influencing the volatility

of exchange rates and interest rates through large-scale funds transfers and

'increasing the tax burden' on the community through tax evasion.[24]

Financial sector crimes

2.25

There are a range of financial crimes including manipulation of the

stock market, fraud against investors and tax crime. According to the ACC, new

technologies and the globalised economy have provided further opportunities for

organised crime - both in terms of new markets and new ways to undertake

criminal activity. This has led to an increase in financial crimes.[25]

Firearms trafficking

2.26

The ACC reports that 'firearms aid criminal activity and can be used to

strengthen an organised crime group's market position'. As a result the

movement of firearms across state borders continues to be of concern to law

enforcement agencies.[26]

High-tech crime

2.27

High-tech crime has been identified as an area of growth for organised

criminal activity. As indicated above, there are two dimensions to high-tech

crime: enabling and facilitating. Technology-enabled crime refers to new crime

opportunities presented by new technologies. An example of this is 'phishing'.

That is, email scams, where the sender endeavours to elicit private information

from the user by pretending to be a legitimate enterprise. Technology-facilitated

crime refers to the use of new technology to undertake traditional crimes. For

example, money-laundering via online transfers.[27]

Other crimes

2.28

The ACC has also reported an international growth in intellectual

property (IP) crime, which includes counterfeiting of a range of products

(DVDs, pharmaceuticals, car parts etc), trademark counterfeiting and illegal

downloads. IP crime has high yields and low penalties, and is therefore a

lucrative market for organised crime.[28]

2.29

Environmental crimes such as wildlife trafficking, poaching and pearl

thefts have all been targeted by organised criminals.[29]

Future trends

2.30

Cultural, political and social changes all impact on the composition of

organised crime groups, the way in which organised crime operates and the focus

of organised criminal activity. New technologies, increasing globalisation,

economic trends and the pace at which change occurs produce particular opportunities

for criminal activity and particular challenges for those charged with the task

of combating organised crime.[30]

2.31

The rapid pace of technological change and, correspondingly, the

'dramatic' impacts of this change on organised criminal activity was commented

on by several witnesses. It was seen to be an immediate and ongoing challenge

for law enforcement agencies. For example, Mr Christopher Keen, Director of

Intelligence of the Crime and Misconduct Commission (CMC) in Queensland

observed:

I think that in three or five years a lot of the organised

crime activity is going to be of a very different complexion to what we have

now.[31]

2.32

The ACC reported that 'emerging areas of potential criminal

exploitation' include financial sector fraud and primary industries.[32]

However, it was noted that illicit drugs will most likely remain the primary

market for organised criminal activity.[33]

Responding to serious and organised crime

2.33

In Australia a range of law enforcement and other government agencies

work in partnership to respond to serious and organised crime. The agencies

involved in responding to serious and organised crime, and the legislative

tools available to them, are discussed in chapter 3.

2.34

At the Federal level, the Australian Crime Commission (ACC) was established

to address federally relevant criminal activity, which section 4 of the ACC Act

defines as:

In practical terms, federally relevant criminal activity

generally equates to serious and organised crime.

2.35

The ACC contributes to the 'fight against nationally significant crime'

through 'delivering specialist capabilities and intelligence to other agencies

in the law enforcement community and broader government'.[34]

The ACC works collaboratively with the AFP, state and territory law enforcement

agencies, the Australian Attorney-General's Department and a range of

Australian Government agencies such as the Australian Customs and Boarder

Protection Service, the Australian Tax Office, the Australian Securities and Investments

Commission, the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation and AUSTRAC.[35]

2.36

Mr Kitson from the ACC emphasised the need for approaches to serious and

organised crime to keep pace with developments in organised crime, including

the changing nature of organised crime groups:

It is true to say that the criminal environment has become

more complex and legislative tools will need to evolve to match the needs of

the criminal environment. Our key intelligence reports show the changing nature

of serious and organised crime. We know that groups are typically flexible and

entrepreneurial and come together and disband as the needs and opportunities

arise. They are increasingly using professional facilitators to blur the lines

between legitimate and illegitimate sources of revenue.[36]

2.37

Similarly, Dr Dianne Heriot from the Attorney-General's Department

stated:

[M]any groups increasingly operate in fluid, loose networks

that come together for specific activities, break and reform. To fight them, we

need similar degrees of flexibility and innovation in our legislative framework

and in our law enforcement.[37]

2.38

The committee heard evidence throughout this inquiry about the

difficulties that Australian law enforcement face in combating serious and

organised crime. Key amongst them are the problems of collecting statistics

about, and mapping trends in, organised crime due to the difficulties in

defining and measuring organised crime.

Defining serious and organised

crime

2.39

Whilst those in the business of monitoring, researching and combating

organised crime share some broad observations about the incidence and

parameters of serious and organised crime, there is limited agreement over how

it should actually be defined. As Dr Schloenhardt submitted:

Despite the omnipresence of criminal organisations in the

region, the concept of organised crime remains contested and there is

widespread disagreement about what organised crime is and what it is not...

Generalisations about organised crime are difficult to make and many attempts

have been undertaken to develop comprehensive definitions and explanations that

recognise the many facets and manifestations of organised crime.[38]

2.40

Dr Schloenhardt went on to note that, in turn, the measures adopted to

respond to organised crime are varied and are designed to meet the different

jurisdictional concepts of serious and organised crime and the potentially

different agendas of those in the position of analysing and combating serious

and organised crime – that is, governments, law enforcement agencies and

researchers.[39]

In brief, how serious and organised crime is defined determines, to an extent,

how serious and organised crime will be approached.

2.41

The Attorney-General's Department submitted that efforts to define

serious and organised crime focus on four elements: 'defining the group;

connecting the group to crime; determining the crimes to be captured; and the

process for determining that the group is criminal'.[40]

2.42

In summary, a 'simple definition' of group is generally employed that

includes the structure of the group (such as minimum number of persons) and the

activities/objectives of the group. The activities/objectives of the group are

what link the group to crime. The crimes to be included in the definition are

ordinarily identified in three ways: 'crimes of a general type with a penalty

of 'x' years imprisonment, listing specific offences, or a combination of these

approaches'.[41]

2.43

Chapter 4 discusses the various legislative approaches which criminalise

association in more detail and considers their respective merits. Appendix 4 provides

a comparative overview of various international approaches to these

definitional elements.

2.44

Serious and organised crime is defined in the Australian Crime

Commission Act 2002 as follows:

Serious and organised crime means an offence:

-

that

involves two or more offenders and substantial planning and organisation, and

-

that

involves, or is of a kind that ordinarily involves, the use of sophisticated

methods and techniques, and

-

that

is committed, or is of a kind that is ordinarily committed, in conjunction with

other offences of a like kind, and

-

is a

serious offence within the meaning of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, an

offence of a kind prescribed by the regulations...[42]

2.45

Mr Kitson from the ACC emphasised the challenges that defining serious

and organised crime presents for the drafting and implementation of

legislation:

I think one of the major challenges...is that there is very

little consistency not only in Australia but internationally about how we

define what serious and organised crime is. It is tremendously hard to define.

We can characterise it as having a number of features: that it is involved in

illicit profit; that it has a level of sophistication; and that there are

elements of intimidation involved. But the drafting of any legislation to deal

with something that is so ill-defined, and is likely to remain a problem that

is challenging to define, will continue to frustrate us for some time.[43]

2.46

Reflecting on the RICO legislation[44]

in the United States, Mr Peter Brady, Senior Legal Adviser with the ACC,

observed that the focus given to the concept of the 'organisation' within the

legislation has diminished relevance within the current organised crime

environment. The RICO Act enables law enforcement agencies to 'target an

organising entity behind a crime' and not simply just the criminal activity

itself.[45]

However, as Mr Brady explained, this type of legislation does not easily

accommodate the more informal, flexible and temporary association of

individuals whose collaboration is driven by a 'business' opportunity:

...one of the difficulties with that type of legislation is

that it revolves around the definition of an organisation. Given that we predominantly

see an entrepreneurial environment for serious and organised crime, a lot of

your attention is focused on defining something which may not exist. It also

gives an opportunity for or reinforces that entrepreneurial coming and going.[46]

2.47

Mr Brady's comments sought to respond to the merits of introducing

RICO-style legislation in Australia (discussed in chapter 4). His remarks also

touched upon the broader issue of the rapidly evolving nature of serious and

organised crime and the importance of keeping pace with these changes.

Legislative measures based on an outdated or otherwise insufficient definition

of organised crime may become less effective or even redundant.

Quantifying serious and organised

crime

2.48

The committee heard from a number of law enforcement agencies about the

difficulties in measuring the level of organised crime in Australia to monitor

changes over time and assess the effectiveness of new approaches to combating

organised crime.

2.49

State and federal law enforcement agencies were only able to provide the

committee with speculative figures or broad-range trends with respect to the

degree of involvement of organised crime groups in criminal activity in

Australia, and the percentage of organised crime undertaken by OMCGS. Chief

Inspector Damian Powell from the South Australia (SA) Police commented:

In terms of the percentage of organised crime attributed

specifically to OMCGs, I think it is a difficult task for anybody to put that

into a percentage quantification, just as it is very difficult to some degree

to cost the impact of organised crime on the community. You can get a best

guess, but I think probably the best way to describe it is to say that outlaw

motorcycle gangs are very prevalent in all levels of crime in South Australia.[47]

2.50

Reflecting on the question of growth of organised crime, Mr Kitson and

Mr Outram from the ACC explained that the increasing sophistication of

Australian criminal intelligence means that benchmarking against data from

previous years to determine trends does not produce accurate results.[48]

Mr Kitson concluded:

I think it would be very easy to look at some of the data we

have got, and to say, ‘Yes, it has expanded quite significantly over the last

five, 10 years, 15 years.’ But I think what has actually happened is that we

have got better at understanding where it is. Would we be in a position in

another five years to say, ‘Let’s benchmark against 2008 and see where we

stand?’ I do not know because I suspect that, in the next five years, we will

also increase our sophistication of understanding how organised crime is

operating. We will get more data from our jurisdictional partners; we will get

more data from the private sector that will help us to understand parts of it

that are probably currently unrecognised as being organised crime activity.[49]

2.51

Mr Kitson went on to note that an accurate picture of the scale of

criminal activity was difficult to ascertain because, in part, private sector

victims of organised crime were reluctant to present such information:

Private sector necessarily protects knowledge about its

losses and might write off something as a bad debt, which we might understand

to be the result of fraudulent activity.[50]

2.52

Superintendent Desmond Bray from the SA Police explained that victims of

organised crime were at times too afraid to report crimes because of

intimidation by the perpetrators.

With extortions and blackmail we believe that what is

reported specifically to the Crime Gang Task Force is very much the tip of the

iceberg because the majority of people are fearful to report and resolve those

issues themselves in other ways. I would suggest that in all or certainly the

majority of victim related crime investigations, victims feel as though they

are at significant threat from gang members if they report the matter.[51]

2.53

Mr Keen from the CMC in Queensland noted that the rather 'fluid'

structure that tends to now characterise organised crime groups contributes to

the difficulty in measuring the nature of organised criminal groups and the

extent of their involvement in organised criminal activity:

You will find that people that we target may come from, for

instance, having links with the Middle East or links to South-east Asia or it

might be established criminal networks within Australia. They will be quite

fluid and move across those boundaries. The fact of the matter is that it is a

very hard thing to measure.[52]

2.54

Mr Outram from the ACC informed the committee that the ACC are working

with academics on the feasibility of conducting economic modelling. He

explained that:

If you can get a handle on the size of the criminal economy,

that of course may give you benchmarks over time to then estimate whether or

not it is increasing or decreasing. That in itself is a challenging proposition

but, as I say, we are engaging with some leading academics, talking to them

about whether or not we can introduce economic modelling in and around AUSTRAC

data, data from the banking sector and so forth. But there is the cash economy,

and that is the challenge. We do not see how big the cash economy is.[53]

2.55

Mr Terry O'Gorman from the Australian Council for Civil Liberties made

the point that the difficulty in quantifying the extent and cost of serious and

organised crime weakens arguments that more police powers are required to deal

with it:

I do not accept that the organised crime problem is serious,

let alone that it is out of control. Nor do I accept that any evidence has been

put before you that the existing suite of police powers is inadequate to deal

with it. The police can come along to a committee such as yours and throw

figures of $8 billion or $12 billion or whatever around, and that attracts

dramatic headlines. I ask myself often when I read it: where is the evidence

that it is $12 billion as opposed to $1 billion and, particularly, where is the

evidence that the existing powers are so inadequate that the police cannot go

and do their job?[54]

2.56

During the course of the inquiry the committee sought on several

occasions to quantify criminal group membership in Australia. The committee was

informed that data was not, as a matter of course, collected in regard to

criminal group membership, and that Australia's federated law enforcement

landscape further restricted the collection and consolidation of this data to

build a national picture.

2.57

The need to quantify accurately the extent of organised crime, and in

particular, to quantify the numbers of criminal groups and those individuals

involved is critical.[55]

In quantifying the size of the problem, to develop a national picture of

criminal groups and group membership, legislation and policy can be accurately developed,

and resources appropriately allocated.

Recommendation 1

2.58

The committee recommends that the ACC work with its law enforcement

partners to enhance data collection on criminal groups and criminal group

membership, in order to quantify and develop an accurate national picture of

organised crime groups within Australia.

A 'harm reduction' approach

2.59

Committee members were told by Mr Bill Hughes, the Director General of

the UK's Serious and Organised Crime Agency (SOCA), that UK law enforcement

faces similar difficulties in terms of measuring the success of various

measures to combat organised crime. In response, SOCA has developed a focus on

harm reduction. The committee was told that this focus was established for

several reasons:

-

Firstly, it is difficult to measure the effectiveness of law

enforcement against serious and organised crime, and there are few meaningful

performance indicators. A focus on harm and harm reduction is seen as a method

which allows the performance of law enforcement to be measured.

-

Secondly, the law enforcement response to organised crime is

shared over a number of agencies. The different focus and activities of these

agencies have not readily allowed a coordinated response to serious organised

crime. A harm reduction focus has allowed the various agencies to develop

specific agency approaches to a shared target. Mr David Bolt, Executive

Director Intelligence at SOCA, told the committee that agencies often tend to

focus on areas which are known. A focus on harm reduction allows agencies to

look outside these known areas of expertise and provides a common focus for

multiple agencies.

-

Thirdly, a focus on harm reduction allows law enforcement to

actively target serious and organised crime and to intervene before a crime is

committed.

Preventative approaches

2.60

Australian law enforcement agencies, along with many of their

international counterparts have begun to recognise the importance of reducing

harm and preventing serious and organised crime from occurring.

2.61

Assistant Commissioner Anthony Harrison from the SA Police said:

...traditionally law enforcement has adopted very much an

investigative approach to the commission of serious and organised crime and

serious offences more generally. Throughout the reform process within this

state we have really tried to be more innovative and to look at prevention

opportunities. As you would probably be aware, police agencies around the world

in the last 15 years in particular have tried to move away from a reactive

approach to servicing their local communities to a more proactive crime

prevention focus.[56]

2.62

A number of different legislative solutions to this traditionally

'reactive' law enforcement role have been mooted and implemented, along with

supporting administrative and policy measures. The fourth and fifth chapters of

this report consider the main legislative models that have been adopted to

prevent serious and organised crime, and discusses the effectiveness of the

different models.

Outlaw motorcycle gangs (OMCGS): a growing concern?

2.63

The committee noted in its 2007 report on serious and organised crime a

growth of OMCG membership and participation in illegitimate activities across

Australia.[57]

2.64

Reflecting on the involvement of OMCGs in serious and organised crime,

Assistant Commissioner Morris from the AFP made the following observation:

We have also started to see a very small element of the

outlawed motorcycle gangs becoming corporatised and using more sophisticated

business structures in their transactions.[58]

2.65

Directly preceding and during the course of the inquiry, significant

legislative developments and other events occurred around the country, which

bought the issue of serious and organised crime more prominently in the

political and public domain. More specifically, the common theme in these

developments was the alleged involvement of motorcycle clubs in serious and

organised crime.

2.66

The following is a brief history of recent events:

-

February 2008 – the South Australian Government introduced the

Serious and Organised Crime (Control) Bill 2007

-

September 2008 – the Serious and Organised Crime (Control) Act

2008 came into effect in SA. Under the Act, a group or club can be declared

an 'organised crime group', which enables various orders to be made to restrict

the movement and associations of the group's members. The legislation was

introduced to specifically suppress motorcycle clubs, which are viewed by the South

Australian Government to present a major organised crime threat in SA.

Responses to the legislation were divided with a number of motorcycle clubs,

academics, legal organisations and individuals strongly opposed to the

legislation, which has been described as 'draconian' and restricting human

rights.[59]

-

March 2009 – a violent confrontation between members of the Hells

Angels and Comancheros Motorcycle Clubs on 22 March resulted in the murder of

Anthony Zervas at Sydney Airport. His brother, Hells Angel member Peter Zervas

was shot and seriously injured in an attack a week later. These events were

seen to be a culmination of escalating OMCG violence in New South Wales (NSW),

which has included drive by shootings and the bombing of an OMCG club house.[60]

-

April 2009 - The Crimes (Criminal Organisations) Control Act

2009 came into effect in NSW. The legislation was introduced as a direct

response to OMCG violent criminal activity and provides a mechanism for

declaring an organisation a 'criminal organisation' and strengthens the

'capability of the New South Wales Crime Commission to take the proceeds of

crime from these organisations and their associates'.[61]

-

April 2009 – The Standing Committee of Attorney-Generals (SCAG)

discussed 'a comprehensive national approach to combat organised and gang

related crime and to prevent gangs from simply moving their operations

interstate' in response to public concern about the violent and illegal

activities of outlaw motorcycle gangs.[62]

-

June 2009 – On 18 June the Western Australia (WA) Police

Minister, the Hon. Rob Johnson MP, announced his intention to take a proposal

to cabinet to introduce legislation that would be based on SA's and NSW's

'tough' anti-organised crime laws.[63]

-

June 2009 – The Attorney-General, the Hon. Robert McClelland MP,

introduced the Crimes Legislation Amendment (Serious and Organised Crime)

Bill 2009 into Parliament on 24 June. The Bill provides for measures agreed

to by state and territory Attorneys-General at their April meeting. The

Attorney-General stated that the measures will: 'target the perpetrators and

profits of organised crime and will provide our law enforcement agencies with

the tools they need to combat the increasingly sophisticated methods used by

organised crime syndicates'.[64]

2.67

The Attorney-General's Department provided a summary of the national

response to this increase in OMCG organised criminal activity:

-

November 2006 – the ACC Board approved the establishment of the

Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs National Intelligence Task Force (the OMCG Task Force)

under the High Risk Crime Groups Determination. The OMCG Task Force superseded

the ACC Intelligence Operation that concluded on 31 December 2006 after it

identified a significant expansion in the activities of OMCGs in 2005-06. The

OMCG Task Force developed national intelligence on the membership and serious

and organised criminal activities of OMCGs to better guide national

investigative and policy action.

-

June 2008 - the ACC Board elected to close the OMCG Task Force

and replace it with a new Serious and Organised Crime National Intelligence

Task Force (SOC NITF), which was to remain in force until 30 June 2009. The SOC

NITF will retain a focus on high risk OMCGs for at least the first 12 months,

but will also allow the ACC to have a broader focus on organised crime occurring

outside the structure of an OMCG.

-

June 2007 - the Ministerial Council for Police and Emergency

Management – Police (MCPEMP) agreed to establish a working group to examine the

issue of OMCGs (the OMCG Working Group). The Final Report of the OMCG Working

Group was completed in October 2007, and made 23 recommendations to enhance a

national approach to combating the problem of OMCGs. The Final Report of the

OMCG Working Group was noted by MCPEMP at its November 2007 meeting.[65]

2.68

Within the South Australian context, the South Australian Government

submitted that OMCGs present the greatest serious and organised crime threat in

that state.[66]

It was argued that a high proportion of organised criminal activity was

attributable to OMCGs and that organised criminal activity was increasing.

2.69

The South Australian Government identified the following threats

presented by OMCGS to SA and other jurisdictions:

-

Illicit drug manufacturing, trafficking and distribution;

-

Infiltration into legitimate industry and partnerships with

professional personnel;

-

Increased sophistication and resourcefulness, making it more

difficult for police to carry out successful investigations;

-

Expansion amongst the greater criminal community, particularly

organised crime syndicates;

-

Inter and Intra gang violence, including blackmail, trafficking

and use of firearms and other weapons;

-

OMCG expansion, including size, scope and influence.[67]

2.70

OMCG organised criminal activity in SA involves:

-

a broad range of criminal activities including the organised

theft and re-identification of motor vehicles; drug manufacture, importation

and distribution; murder; fraud; vice; blackmail; assaults and other forms of

violence; public disorder; firearms offences; and money laundering;

-

the recruitment of street gangs by OMCGS to undertake 'high risk

aspects of their criminal enterprise'; and

-

a reliance by OMCGS on professionals, such as lawyers and

accountants, 'to create complicated structures to hide the proceeds of their

crimes'.[68]

2.71

Assistant Commissioner Harrison from the SA Police outlined the growing

connection between street gangs and motorcycle clubs:

We have certainly seen the linkage [between motorcycle clubs]

with street gangs and youth gangs in this state, and I think that has also been

seen in other jurisdictions around Australia. We are now seeing individual

members of street and youth gangs graduating to nominees or prospects of outlaw

motorcycle gangs, and we are also seeing some of them made full members of

outlaw motorcycle gangs. We know that there is a direct correlation between

some outlaw motorcycle gangs and some street gangs.[69]

2.72

Consistent with the trends in organised crime groups outlined above,

Assistant Commissioner Harrison further observed that the boundaries between

motorcycle clubs and other organised crime groups were no longer rigid with

groups forming previously unlikely alliances:

We are finding that there is diversification and

interrelationships between outlaw motorcycle gangs and the more traditionally

based ethnic serious and organised groups of the past.[70]

2.73

The perceived prevalence of OMCG criminal activity was not, however,

consistent across all jurisdictions, with some states – Victoria for example –

presenting a picture of organised crime in which OMCGs played a less central

role. Detective Superintendent Paul Hollowood from Victoria Police stated:

I think we have regained something like $77 million in assets

from Tony Mokbel. That is serious organised crime. I do not see those types of

assets with guys riding bikes—nowhere near that. It is where the money is and

where it is being derived that is the best indicator for us as to where

organised crime is sitting.[71]

2.74

Reflecting on motorcycle club members, Detective Superintendent

Hollowood commented that:

Some are genuine motorcycle enthusiasts I suppose. They are

not at the serious end of our organised crime problem in Victoria. I appreciate

that the South Australian and Western Australian situations are different. It

appears that it is a larger threat to them in those states. However, from a

Victorian perspective, we have bigger fish to fry with what we are doing and

focusing on. The whole OMCG argument can be an unhealthy distraction. I do not

think it is just law enforcement agencies that talk about it; there seems to be

a real preoccupation in the media with the subject as well.[72]

2.75

In Queensland, witnesses from the Queensland Police Service (QPS) observed

that there is OMCG involvement in organised criminal activity but warned

against concentrating efforts on 'traditional' crime groups. Deputy

Commissioner Stewart from the QPS stated:

The service is also mindful of the dangers inherent in

focusing too intensively on what may be seen as traditional organised crime

groups that are both visually observable and publicly familiar such as outlaw

motorcycle gangs, or OMCGs.[73]

2.76

Consistent with the trends in criminal group activity discussed earlier

in the chapter, Deputy Commissioner Stewart went on to point to the

increasingly fluid and temporary nature of criminal networks.[74]

2.77

Mr Keen from the CMC in Queensland informed the committee that in view

of the relatively flexible nature of organised crime groups the CMC has adopted

a 'market-based' approach to dealing with serious and organised crime. He

explained that:

We are looking at the crime markets and from there we go and

look at the groups that may be perpetrating those crimes. We look at things

like illicit drug markets, we look at property crime, we look at

money-laundering, and from there it is really a matter of whoever is actually

involved in that they will be the subject of our intelligence and investigation

action. I put that in context to show that we are looking very much of the actual

activities and the markets when we target any particular group.[75]

2.78

Reflecting on the participation of OMCGs in organised crime, Mr Kitson

from the ACC observed:

Outlaw motorcycle gangs...are more structured, enduring and

more easily identifiable than many other groups that we deal with. However,

they are not typical of the majority of organised crime entities that attract

national law enforcement attention. While other syndicates or networks may

share a common ethnicity or ethos, these are rarely defining characteristics.

In reality there is little if any public self-identification by the majority of

the key criminal syndicates which we target.[76]

2.79

Whilst not disputing the participation of OMCGs in organised crime in

Australia, Mr Kitson was clear that this was not the issue on which the ACC

currently believes it should focus its efforts. Mr Kitson explained that the

ACC's strategy is to 'identify serious criminal targets through identification

of criminal business structures and money flows'. Correspondingly, the ACC's

focus from a legislative perspective is on ways to 'improve and tighten

legislation' in order to facilitate the interruption of the financial affairs

of suspected criminals.[77]

Organised crime groups and groups

with organised crime involvement

2.80

A number of witnesses made the distinction between the involvement of

groups in organised crime and the involvement of individual group members in

organised crime. Mr Kitson from the ACC stated:

OMCGs continue to feature in the Australian criminal

landscape; of that there is no question. We would make a distinction between

the operation of those groups as networked entities and the criminal

enterprises of a number of the significant individuals within those groups.

There is no doubt that in some instances those individuals operate entirely as

individuals.[78]

2.81

Mr Kitson went on to explain that in some cases those OMCG members

operating criminally as individuals carried 'the threat of menace that goes

with the OMCGs. He further stated that:

It is true to say that in any analysis of some of the

nationally significant crime figures you will find people who have associations

with outlaw motorcycle gangs, but I do not know that that would necessarily

mean that you would characterise the outlaw motorcycle gangs themselves as

being the primary criminal threat in this country.[79]

2.82

Similarly, Detective Superintendent Hollowood from Victoria Police

informed the committee that:

You generally find it is the individuals within the gang who

are actually engaged in organised crime activity. However, the stated charter

or the mandate of the OMCG is to be like a brotherhood, to be very protective

of the members and not to inform on other members. Because of that it is very

easy for criminal individuals to operate.[80]

2.83

The same point was made by Superintendent Gayle Hogan from the

Queensland Police:

There are people within the groups who work independently.

They work as a group within the group and they align themselves with other

areas. So there are all ambits of that sort of criminality, but it does not

necessarily mean the entire club is involved. They sometimes use being part of

that criminal entity as a means of extortion or threat or to be able to stand

over potential witnesses or victims.[81]

Motorcycle clubs: an unfair target?

2.84

The committee received evidence from a number of individuals and

motorcycle clubs arguing that motorcycle clubs were being unfairly targeted. The

involvement of some individual bikers in criminal activity was not disputed. However

some witnesses alleged that motorcycle clubs had no involvement in organised

crime while others contested the extent of this involvement and expressed the

view that motorcycle clubs were being unjustly maligned.

2.85

Mr Errol Gildea, President of the Hells Angels Motorcycle Club Queensland,

refuted suggestions that motorcycle clubs were involved in organised crime.[82]

Similarly, Mr Gary Dann, Road Captain of the Bandidos MC, commented:

The club does not break the law, as a rule. If individuals

do, that is their business. They should be dealt with. But we are not an

organised crime outfit.[83]

2.86

Mr Edward Hayes, a member of the Longriders Christian Motorcycle Club (Longriders

CMC) in South Australia observed:

Our own members and many recreational riders have noticed a

marked increase in the past couple of years in the public's and uniformed

police officers' attitude towards them. They (The public and average cop on the

street) can only go on what they’ve been told and the past six years of the

politics of fear has done its job.[84]

2.87

Similarly, reflecting on South Australia Dr Arthur Veno and Dr Julie van

den Eynde in their submission characterised that state's attitude to bikers as

the 'Great South Australian Bikie Moral Panic'. They argued that a 'politics of

fear' was in operation which presented OMCGs as the 'enemy within' and underpinned

the recent introduction of 'draconian' legislative measures.[85]

2.88

The perception that motorcycle clubs are publicly demonised was discussed

within the Queensland context. Mr Gildea recounted an instance of alleged unfair

treatment from the Queensland Police and stated: 'We are under a barrage of

attacks from everywhere'. He went on to remark:

I would love to see the day when parliamentarians can come

out to the clubhouse and have a look and make up their own minds and meet us on

an individual basis, because we are not the monsters that you guys think we

are. We are as human as everybody else. We bleed the same colour as everybody

else.[86]

2.89

Mr Edward Withnell, a long-term member of the 'Outlaw Motorcycle

Community' in WA, argued that bikers have been 'stereotyped' and

'de-humanized'. He submitted:

We Bikers are not homogeneous, we are heterogeneous. Like

yourselves, we have differences within ourselves, as well as between

ourselves...We are not driven by drug wars or any of the fanciful creative writings

of the media or 'secret police'.[87]

2.90

Mr Adam Shand, a journalist who has worked on organised crime for a

number of years, including the Victorian 'Underbelly' era and more recently SA

motorcycle club involvement in crime, contrasted organised crime during the

'Underbelly era' with the kind of criminal activity undertaken by some

motorcycle club members in South Australia:

You are talking about serious organised crime there

[Victoria]. What we are seeing here [SA motorcycle groups] is disorganised

crime. We are seeing a lot of street level stuff—assaults, small extortion

cases and drug manufacture and supply. Where are these massive convictions? Where

are these massive seizures that we keep hearing about?

2.91

Mr Shand argued that the connections between motorcycle clubs and

serious and organised crime are overstated. He informed the committee that:

There are some clubs that are completely free of crime. There

are others that have some chapters that are riven with crime. Others have some

criminals in them. There is an attempt at regulation, certainly in recent

years. The clubs are not without some sensitivity towards community attitudes.

There have been attempts by more moderate members in clubs to bring others to

heel because they want to continue their lifestyle, as well.[88]

2.92

Pursuing a related theme, Mr Gildea, Hells Angels Motorcycle Club

Queensland, observed that club membership 'is about love and respect; it is not

about hate' and confirmed that any person interested in motorcycles and the

values of love and respect would likely be welcomed into a club 'if they were a

good Australian person'.[89]

However, the committee was informed that this culture is predominantly

masculine and women are largely excluded.[90]

2.93

Mr Edward Withnell from WA claimed that OMCGs and other 'minority'

groups were being used as scapegoats for the real participants in serious and

organised crime:

Outlaw motorcyclists and many other ethnic and minority

groups and individuals have been 'set-up as fall-guys', persons on whom to

shift the focus away from the level of crime and corruption that the ACC is

best suited to investigate.[91]

2.94

Several witnesses noted that the 'code of silence' adopted by motorcycle

clubs contributed to the negative perceptions of the clubs and made it

difficult for law enforcement officers to bring individual bikers engaged in

criminal activity to justice. For example, Mr Withnell informed the committee

that 'immoral journalists' and 'dishonest police officers' perpetuated 'lies'

about motorcycle clubs and it was the bikers decision not to engage with this

unfair representation that had resulted in the poor public perception of bikers.[92]

2.95

Mr Hayes, Longriders Christian MC, explained that the 'code of silence'

had arisen from a deep distrust of the police, of politicians and of the media:

From a social kind of aspect, when we have a look at the

profile of the average man in a club, he has probably got a whole life history

of believing that society is against him. Why should he trust a politician; why

should he trust a police officer? That is the background to the code of

silence—it is the distrust. That goes for the media as well. Often clubs will

not talk to the media because they have tried it in the past and they have been

represented in a different way to what their intention was.[93]

2.96

Biker witnesses emphasised positives aspects of motorcycle club

membership noting the pleasure of riding, the commitment to rules and values, the

importance of the social support network provided through club membership and a

'sense of belonging for individuals who often believe that society has rejected

them'.[94]

2.97

Mr Shane 'Shrek' Griffiths, a 'proud Australian biker', submitted:

In my journeys through out our great nation I have met many a

Colourful biker from all walks of life. These gentlemen as individuals were

just like me with the same love for motorcycling. I have also had the pleasure

of Associating with many of them as a guest of their motorcycle club, weather

it be a fund raising ride, a Poker run, Bike and Tattoo show or just as a guest

on a club run.[95]

2.98

Mr Robbie Fowler, President of the Outcasts Motorcycle Club Australia,

presented an account of a troubled early life and concluded:

I never respected or liked my self I hated Authority and I

resent woman, I was released in 1990 went to the Bike club, got married and had

five children. ... One must understand the club saved my life and my liberty, as

my actions positive or negatives, reflects as you know on my Brothers in the

club. I have not been convicted of an offence in 10 years yet I fought men

every day since I was eight. The Brotherhood the code of ethics and the old

Australian Values is what has taught me respect and how to love. I am happy that

I now have respect for my peers; blessed to have learned how to love, and have

the pleasure of helping my five kids grow up with the values that made Australia

once the greatest free country of people from all over the world.[96]

2.99

Mr Gildea argued that these positive aspects of motorcycle clubs tended

to be overlooked:

You never get to hear about the good things we do or all the

charity events that we raise money for either; it is always about the drugs and

stuff. Yes, there are individuals who have been caught and do drugs.[97]

2.100

However, evidence from other witnesses was at odds with the views

outlined above. Assistant Commissioner Harrison from SA Police was adamant that

biker involvement in serious and organised crime in South Australia has grown

in recent years. He argued that individual bikers and/or motorcycle clubs are

implicated in a high proportion of organised criminal activity.[98]

2.101

Concurring with his colleague's observations Chief Inspector Powell

commented:

...it is fair to say from a South Australian perspective that

outlaw motorcycle gangs are involved at all levels of crime, from the

street-level public violence that causes community concern through to

sophisticated drug manufacture and distribution which extends not just within

the South Australia but across jurisdictions within Australia.[99]

2.102

In the NSW Parliament, The Hon. Michael Gallacher outlined a history of

'violent outlaw motorcycle gang crime' in that state and quoted the NSW Police

Force Assistant Commissioner Nick Kaldas's 2006 observation that:

Just because bikies deliver teddy bears to children's

hospitals once a year doesn't mean they're not criminals the other 364 days.[100]

2.103

Detective Superintendent Hollowood from the Victoria Police Force,

whilst questioning the level of involvement of OMCGs in organised crime and

describing them as an easy target was, nonetheless, forthright in his appraisal

of OMCGs:

I think sometimes it is easier to jump to the OMCGs. It is

very easy to portray organised crime and the threat of it by looking at OMCGs.

They exist in every state in Australia. I will not go as far as saying that

they have become a scapegoat, because by no means are they sitting there as

church choir groups.[101]

2.104

The level of OMCG involvement in serious and organised crime is

difficult to clearly establish. The committee acknowledges that it varies

across the states. However, the committee is persuaded by the ACC that OMCGs

are a visible and therefore prominent target in both the political and public

arenas, and that serious and organised crime often involves a level of

sophistication or capacity above that of many OMCGs.

CHAIR—...What relationship is there between motorcycle clubs

and organised crime, if any?

Mr Gildea—None.

Mr Dann—'Disorganised’, if anything.[102]

2.105

However, the committee also notes that if OMCG members wish to challenge

public and media perceptions of them, bikers must take an active role in that

process, including by proactively assisting police by clearing from their ranks

any criminal elements.

Conclusion

2.106

Organised crime is undoubtedly a widespread phenomenon in Australia and

internationally. There are a number of broad features that can be said to

characterise organised crime – most notably, organised criminal activity is

driven principally by the promise of financial gain and is generally well-planned,

progressively more sophisticated, and increasingly traverses geographic and demographic

boundaries.

2.107

In spite of these common characteristics, jurisdictional differences and

the historical choices that the various states have made to deal with these

differences means there is no single approach to serious and organised crime in

Australia. Nor is there necessarily any one right approach. Notwithstanding

this, the committee believes that current trends – in particular the increasingly

multi-jurisdictional and transnational character of serious and organised crime

– mean that greater legislative consistency, enhanced administrative

arrangements and law enforcement capabilities are required. These issues are

discussed in the following chapters.

2.108

Overwhelming, evidence on the changing character of organised crime

groups from tightly structured, hierarchical, enduring groups to flexible,

market-driven networks signals, the committee believes, the need for a

strategic response that targets in the first instance the criminal market or

activity. This is considered further in the chapter 3 which outlines the

legislative responses of the different jurisdictions to serious and organised

crime.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page

Top

|