Bills Digest No. 8, 2017-18

PDF version [1,373KB]

Dr Rhonda Jolly

Social Policy Section

8

August 2017

Contents

The Bills Digest at a glance

Purpose of the Bill

Structure of the Bill

History of the Bill

Background

Ownership and reach rules

Hawke Government

Howard Government

Box 1: current media rules

Rudd-Gillard Government

Abbott and Turnbull Governments

Anti-siphoning

Committee consideration

Selection of Bills Committee

Senate Standing Committee for the

Scrutiny of Bills

Senate Environment and Communications

Legislation Committee

Policy position of non-government

parties/independents

Australian Labor Party

The Australian

Greens

One Nation, Nick Xenophon Team and

Independents

Position of major interest groups

Industry

Previous comment

Re-introduction of reform proposal

The 2017 Bill

Media and other commentators

Audiences

Financial implications

Statement of Compatibility with Human

Rights

Parliamentary Joint Committee on

Human Rights

Key issues and provisions

Schedule 1

Schedule 2

Schedule 3: Part 1

Schedule 3: Part 2

Schedule 4

Schedule 5

Schedule 6

Broadcasting Services Act 1992

Radiocommunications Act 1992

Schedule 7

Comment

Appendix A: major media interests

snapshot: June 2017

Date introduced: 15

June 2017

House: House of

Representatives

Portfolio: Communications

and the Arts

Commencement: the day

after the Act receives Royal Assent with the following exceptions:

- Schedule

3, Part 2: six months after Royal Assent

- Schedule

5, items 2 and7: 1 July 2016

- Schedule

5, items 3 to 5 and 8 to 10: 1 January 2017

- Schedule

6, Part 2: 1 July 2017

Links: The links to the Bill,

its Explanatory Memorandum and second reading speech can be found on the

Bill’s home page, or through the Australian

Parliament website.

When Bills have been passed and have received Royal Assent,

they become Acts, which can be found at the Federal Register of Legislation

website.

All hyperlinks in this Bills Digest are correct as

at August 2017.

The Bills Digest at a glance

Purpose

The purpose of the Broadcasting Legislation Amendment

(Broadcasting Reform) Bill 2017 (the Bill) is to amend the Broadcasting

Services Act 1992 to:

- repeal

the ‘75 per cent audience reach rule’ and the ‘2 out of 3 cross-media control

rule’

- amend

local programming obligations and introduce additional obligations for a regional

commercial television broadcaster which undergoes a change of control of its

licence and as a result, the licence is absorbed into a group of commercial

television licences whose combined licence area populations exceeds 75 per cent

of the Australian population

- amend

the anti-siphoning scheme and the anti-siphoning notice

- abolish

television and radio licence fees and datacasting charges

- establish

tax collection and assessment arrangements for an interim transmitter licence

tax and establish a statutory review of the tax arrangements in 2021

- establish

a transitional support payment scheme for commercial broadcasters which will

operate for five years during the transition to the interim transmitter licence

tax arrangements.

Background

- Since

the advent of new media technology—which has brought the Internet and its

promises of greater diversity of sources, multiple news and information voices

and innovative practices—some media operators have become alarmed by what they

maintain are the adverse effects of over-regulation of the traditional media.

Consequently, they have intensified their long-standing advocacy for removal of

certain rules, such as those targeted in this Bill, arguing that this is vital

for their survival.

- The

Turnbull Government has attempted to respond to the concerns of free-to-air

broadcasters by introducing legislation to remove two important media

regulations—the audience reach rule and the rule which prevents the ownership

of radio, television and newspaper outlets in any one licence area (the two out

of three rule).

- Two

previous attempts to remove these rules have been unsuccessful. This Bill

represents a third attempt at removing the rules noted above. It also contains

additional provisions which have the support of the industry. The Government

considers the package in this Bill and the Commercial Broadcasting (Tax) Bill

2017 will give free-to-air broadcasters ‘flexibility to grow and adapt in the

changing media landscape, invest in their businesses and in Australian content,

and better compete with online providers’.

Key issues

- On

the one hand this Bill is not controversial as there is general agreement that some

media rules, such as the audience reach rule, are outdated. There is also

agreement that licence fee relief will assist the traditional media to cope

with the changing media environment.

- One

aspect of the changes outlined in this Bill has proven controversial, however.

This is the proposal to remove the cross-ownership rule. A number of sources,

citing the considerable concentration of television, radio and newspaper

ownership in Australia, consider that this rule needs to be preserved to help

to limit further concentration. Labor and the Australian Greens have taken this

stance.

- The

industry supports the changes proposed in this Bill, but only if it is passed

in total.

Purpose of

the Bill

The purpose of the Broadcasting Legislation Amendment

(Broadcasting Reform) Bill 2017 (the Bill) is to amend the Broadcasting

Services Act 1992 to:

- repeal

the ‘75 per cent audience reach rule’ and the ‘2 out of 3 cross-media control

rule’

- amend

local programming obligations and introduce additional programming obligations for

a regional commercial television broadcaster which experiences a change of

control of its licence and as a result of that change of control, the licence is

absorbed into a group of commercial television licences whose combined licence

area populations exceeds 75 per cent of the Australian population

- amend

the anti-siphoning scheme and the anti-siphoning notice

- abolish

television and radio licence fees and datacasting charges payable by commercial

broadcasters

- remove

apparatus taxes payable by commercial broadcasters

- establish

tax collection and assessment arrangements for an interim transmitter licence

tax and establish a statutory review of the tax arrangements in 2021

- establish

a transitional support payment scheme for commercial broadcasters which will

operate for five years during the transition from revenue-based licence fee and

charge arrangements to the interim transmitter licence tax arrangements.

Structure

of the Bill

The Bill consists of seven Schedules:

- Schedules

1 and 2 to the Bill proposes to repeal the ‘75 per cent audience reach rule’

and the ‘2 out of 3 cross-media control rule’

- Schedule

3 will increase local programming obligations that currently apply in

aggregated markets (and Tasmania) and introduce local programming obligations

in non-aggregated markets, for regional commercial television broadcasting

licences affected by a ‘trigger event’

- Schedule

4 will extend the anti-siphoning automatic delisting period, remove

multi-channelling restrictions which currently apply to free-to-air

broadcasters and repeal and replace the Schedule to the anti-siphoning notice

to reduce the list of anti-siphoning events

- Schedule

5 will abolish broadcasting licence fees and datacasting charges currently

imposed on commercial broadcasters

- Schedule

6 deals with administrative arrangements for the transmitter licence tax it is

intended will be imposed on commercial broadcasters under the Commercial

Broadcasting (Tax) Bill 2017 (the Tax Bill).[1]

Schedule 6 also sets out transitional support payments to regional broadcasters

that may be disadvantaged by the new tax arrangements for a period of five years

and

- Schedule

7 requires the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) to conduct

a review after five years into the new taxation arrangements implemented by

this Bill and the Tax Bill.

History of the Bill

The first of the media reform Bills proposed by the

Turnbull Government was the Broadcasting Legislation Amendment (Media Reform)

Bill 2016 (the March 2016 Bill), which was introduced into the 44th Parliament

on 2 March 2016.[2]

This Bill had not passed the House of Representatives when Parliament was

prorogued on 15 April 2016. Hence, the Bill lapsed at that time. A second

Bill, with the same title and content, was introduced into the 45th Parliament

in September 2016.[3]

This Bill was passed by the House of Representatives in November 2016 and

introduced into the Senate in December 2016. It was not debated in that chamber

prior to the introduction of this Bill.

Schedules 1 to 3 of the current Bill replicate the

September 2016 Bill. Schedules 4 to 7 are new.

A considerable amount of the information in the background

section of this Digest relating to the ownership and reach rules is taken from

the Bills Digest to the second media reform Bill, the September 2016 Bill.[4]

Background

Ownership

and reach rules

The federal government became concerned in the 1930s that

a trend towards media concentration in Australia would be detrimental to the public

interest if it was allowed to continue without restraint.[5]

To counter the trend the Government introduced media ownership and control

regulations which restricted the number of commercial broadcasting stations

that could be owned by an individual or company—four in any one state and eight

throughout the country and only one metropolitan station per state.[6]

The 1930s regulations were not successful and from that

time to the present, various governments have continued to address what has

become an ongoing trend towards media concentration. This has resulted in the

strengthening of regulations by some governments and the relaxation of rules by

other administrations. However, despite the various strategies employed to curb

media concentration, Australia now has one of the most concentrated media

environments in the world.[7]

What have now come to be called traditional media operators—television

and radio broadcasters and the press—have protested that the majority of

regulations governments have imposed have been onerous. Not only have

restrictions been onerous, according to the media operators, regulation has

stifled the development of their businesses.

Since the advent of new media technology—which has brought

the Internet and its promises of greater diversity of sources, multiple news

and information voices and innovative practices—traditional media operators

have become so alarmed by what they maintain are the adverse effects of

regulation that they have intensified advocacy for the removal of what they

argue are outdated rules. Their message has been that removal of rules, such as

those targeted in this Bill, is vital for their survival.

The current media ownership and control regulations are

the result of legislation introduced by a Labor Government under Bob Hawke and

a Coalition Government led by John Howard.

Hawke

Government

One report commissioned by the Hawke Government into the

broadcasting media recommended that the government encourage local ownership,

control and presence and prohibit the ‘buying and selling of licences for

purely investments purposes’.[8]

Another report suggested that there was a need to strengthen the position of

regional media owners in relation to their metropolitan counterparts, and that

this could occur if a market reach limit was imposed and supplemented with a

minimum number of owners rule.[9]

These reports were partly responsible for the introduction

of legislation which changed media ownership rules in 1987. An ownership rule

which prevented broadcasters from owning more than two television stations

(introduced by the Menzies Coalition Government in 1956) was replaced by the

audience reach rule.[10]

This rule stated that a person was not to control commercial television

licences reaching more than 60 per cent of the population; more than one

commercial licence in the same licence area; more than two commercial radio

licences in the same area and in any area a combination of any two of the

following—a commercial television licence, a commercial radio licence or a

major newspaper.[11]

The broadcasting reach rule was later amended to allow for an audience reach of

75 per cent of the population.[12]

Treasurer Paul Keating is often quoted as proclaiming that

the cross-media changes in the Hawke Government’s legislation would mean that

media proprietors would have to choose whether they wanted to be ‘queens of the

screen or princes of print’.[13]

According to a number of commentators, rather than this being what the

legislation is remembered for, it is often cited as producing ‘the greatest

media carve-up’ in Australia’s history. That is, the regulatory change which

delivered more media concentration than any other.[14]

Howard

Government

When the Howard Government was elected in 1996 it

announced that it was committed to abolishing what it saw as anachronistic

limitations on the media.[15]

To this end, it directed the Productivity Commission (PC or the Commission) to

inquire into broadcasting regulation and to provide advice ‘on practical

courses of action to improve competition, efficiency and the interests of

consumers in broadcasting services’.[16]

In so doing, the PC was to keep in mind that legislation which restricted competition

should be retained only if the benefits to the community as a whole outweighed

the costs and if the objectives could be met only through restricting

competition.[17]

In its report published in 2000, the Commission

recommended that certain media regulations should be removed.[18]

The PC added one critical proviso that reform should only occur once a more

competitive Australian media environment had been established.[19]

It also recommended that the media landscape should be structured so that

broadcasters delivered services that took into account the public interest.[20]

The Howard Government did not accept the PC’s

recommendation, arguing that subjective judgement by an individual or

organisation would inevitably occur in deciding what constitutes the public interest

and that this would create uncertainty for the media industry.[21]

Nonetheless, the Government included public interest concessions in its media

reform legislation which passed into law in 2006.[22]

These were the result of negotiations with some of its own backbenchers who

were concerned that changes to regulations would have adverse effects for

regional media. The changes resulted in the four/five rule that permits

transactions involving commercial radio licensees, commercial television

licensees and associated newspapers, including cross-media transactions, to

occur subject to conditions under which there needs to remain a minimum number

of separately controlled commercial media groups or operations—sometimes

referred to as voices—in a relevant radio licence area following such

transactions.[23]

The minimum number of commercial media groups which must

remain in a mainland metropolitan radio licence areas is five, and in regional

areas it is four. If the number of media groups drops below these stipulated levels

then an ‘unacceptable media diversity situation’ is said to exist.

The Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA)

has established a Register of Controlled Media Groups (RCMG), the job of which

is to identify who owns and controls the media groups in each licence area in

order that compliance with the rules can be monitored and breaches of the rules

investigated by the regulator.[24]

The full list of media ownership and reach regulations is

summarised in Box 1.

Box 1:

current media rules

|

75 per cent rule (audience reach rule)

A person, either in his or her own right or as a director

of one or more companies, must not be in a position to exercise control (see

below) of commercial television broadcasting licences which have a combined

licence area population that exceeds 75 per cent of the population of

Australia.

Two out of three rule (cross-media ownership rule)

A person can only control two of the regulated media

platforms (commercial television, commercial radio and associated newspapers)

in a commercial radio licence area.

Five/four rule (minimum voices rule)

There must be at least five independent media voices in

metropolitan commercial radio licence areas (the mainland state capital

cities) and at least four in regional commercial radio licence areas.

One to a market rule

A person (either in his or her own right or as a director

of a company) must not exercise control over more than one commercial

television broadcasting licence in a licence area.

Two to a market rule

A person (either in his or her own right or as a director

of a company), must not control more than two commercial radio broadcasting

licences in the same licence area.

Control

A person whose interest in a company exceeds 15 per cent

is regarded under the current rules as being in a position to exercise

control of that company.

The rules also acknowledge that control can be exercised

in other ways, such as through a person being in a position to appoint a

majority of the board of directors of a company.

|

Rudd-Gillard

Government

The Independent Convergence Review Committee (CRC), formed

under the Rudd-Gillard Government, pointed out in 2013 that since the 1990s and

in the short time since the 2006 media changes had come into effect, the media

landscape had experienced major upheavals as a result of media convergence due

to technological advances.[25]

The CRC considered that existing statutory control and media ownership and

diversity rules are based on distinctions between traditional broadcasting and

print media which no longer exist, as media enterprises increasingly operate

across a range of platforms. The CRC recommended the abolition of the current

rules and proposed instead that a public interest test could be used in

conjunction with the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s (ACCC)

media and merger powers to ‘provide sufficient safeguards to maintain diversity

and a competitive market’.[26]

The Rudd-Gillard Government tried to implement media

reforms, some of which were based on the CRC’s recommendations. But most of

Labor’s plans for media reform were subject to intense criticism from within

the media. Indeed some critics labelled some of its proposals ‘reckless and

flawed media reforms’ and ‘a danger to democracy and free speech’.[27]

The Rudd-Gillard Government’s attempt at reform was, in fact, spectacularly

unsuccessful and abandoned by the Government.

Abbott and

Turnbull Governments

Following the election of the Abbott Government, in early

2014 the then Communications Minister Malcolm Turnbull declared that he was

‘fairly sympathetic’ to relaxing media diversity and ownership regulations.[28]

The Prime Minister, Tony Abbott, however, was reportedly reluctant

to attempt any reform unless a broad consensus within the industry on the form

it would take could be identified.[29]

In late 2015 regional television networks began a campaign

to allay disquiet that had been expressed by regional Members of Parliament

about the consequences of lifting media restrictions.[30]

The ‘Save Our Voices’ campaign, led by Prime Media, Southern Cross Austereo,

WIN Corp and Imparja, proposed that any changes to regulations should have to

include the proviso that a buyer of a regional television station would be

required to maintain that station's local news services at existing levels.[31]

In addition, the networks suggested that buyers of regional networks should be

required to provide a minimum local news service in markets where no such

requirement currently exists.[32]

Added to this campaign were reports that in effect, both

the 75 per cent reach rule and the two out of three rule were being ignored,

regardless of the directives of the BSA following legal advice that had

led to a Seven Network decision to stream its channels via the Internet to

lap-tops or mobile phones from Melbourne Cup Day in November 2015.[33]

This decision was based on advice that streaming programs was not covered by

the BSA.[34]

In 2016 Mitch Fifield, who became Communications Minister

after Malcolm Turnbull replaced Tony Abbott as Prime Minister in September 2015,

introduced into the Parliament reform proposals which he labelled the most

significant reforms to media laws in a generation, ‘supporting the viability of

our local organisations as they face increasing competition in a rapidly

changing digital landscape’.[35]

Minister Fifield’s first media reform Bill lapsed with the

dissolution of the 44th Parliament, but following the 2016 election, the

Government made a further attempt to change the media landscape with the

introduction into the 45th Parliament of a revised Broadcasting Legislation

Amendment (Media Reform) Bill 2016.[36]

This Bill was passed by the House of Representatives on 30 November 2016, but

not debated by the Senate prior to the introduction of the revised reform

package in this Bill.

Anti-siphoning

From 1982 when the Fraser Government asked the Australian

Broadcasting Tribunal (ABT) to inquire into the possible social, economic or

technical implications that could accompany the introduction of cable and

subscription television to Australia, free-to-air broadcasters have argued that

siphoning programs would be an inevitable consequence of the introduction of pay

television and that this would have considerable social costs for audiences.[37]

According to the free-to-air broadcasters, the only way to prevent siphoning was

to introduce an anti-siphoning scheme.[38]

In opposition, potential subscription television operators told the ABT that

such a scheme would prevent them from competing with free-to-air broadcasters

to buy programs and some sporting bodies also opposed the introduction of an

anti-siphoning regime.[39]

After a number of investigations into the issue of

siphoning and its consequences, the Fraser Government’s Labor successor decided

to impose the anti-siphoning regime on pay television. There are few who would

deny that powerful free-to-air broadcasters, such as Kerry Packer, had some

considerable influence on this decision which saw the Hawke Government deny pay

television access to a vast amount of sports programming.[40]

Once the list was in place subscription television

providers at times attempted to circumvent its provisions so they could show certain

sports on their channels, while the free-to-air broadcasters were accused of

making arbitrary decisions about showing programs, thereby undermining the stated

intention of the list.[41]

In response, the Government made changes to the list, such as introducing

anti-hoarding provisions.[42]

As part of its major inquiry into broadcasting in 2000,

the Productivity Commission (PC or the Commission) reviewed the anti-siphoning

scheme and concluded that it gave free-to-air broadcasters ‘a competitive

advantage’ over subscription broadcasters and disadvantaged sport organisations

by decreasing their negotiating power in marketing their products.[43]

In 2009 the Commission’s annual review of regulatory burdens on business called

anti-siphoning ‘a blunt, burdensome instrument that is unnecessary to meet the

objective of ensuring wide community access to sporting broadcasts’.[44]

During a major inquiry into the anti-siphoning scheme in the

same year Australian Subscription Television and Radio Association (ASTRA)

labelled it antiquated, anticompetitive and dramatically limiting to Australian

viewers’ choice to watch live sport. Moreover, ASTRA saw the list as

detrimental to sports codes and grass roots sports competitions. [45] In contrast,

Free TV Australia argued that the existence of the list ensured that all Australians

have access to sport on television, not just the minority who can afford to pay

for a subscription television package.[46]

Until recently the views of free-to-air broadcasters and

subscription television providers have remained rigidly opposed. With the

announcement of a revised reform package in May 2017, however, it appeared that

a reluctant compromise had been reached with the representative bodies for both

these media sectors praising the reforms proposed in this Bill.[47]

Committee

consideration

Selection

of Bills Committee

The Selection of Bills Committee referred both the

previous media reform Bills to the Senate Environment and Communications

Legislation Committee for inquiry and report.[48]

The Selection of Bills Committee recommended that this Bill is not referred to a

committee for inquiry.[49]

Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

The Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

reported in March and September 2016 that it had no comment on either iteration

of the 2016 media reform Bills.[50]

In June 2017 it reported it had no comment on this Bill.[51]

Senate

Environment and Communications Legislation Committee

The May 2016 report of inquiry into the first of the

previous media reform Bills recommended that the Bill should be passed subject

to a change to a provision relating to trigger events in regional areas.[52]

The second Senate inquiry noted in its report published in November 2016 that

the change previously recommended by the Committee was included in the revised 2016

Bill and that otherwise the proposed legislation was identical to the Bill

examined by the Committee appointed in the previous Parliament.[53]

Policy

position of non-government parties/independents

Australian Labor Party

With reference to the 2016 media reform

Bills Labor’s communications spokesperson at the time, Jason Clare, noted that

in the Opposition’s view removing the 75 per cent reach rule was relatively

uncontroversial.[54]

However, Mr Clare was not convinced that removing the two out of three rule

would be compatible with media diversity.[55]

In their dissenting report to the

November 2016 Senate inquiry report Labor Senators Anne Urquhart and Anthony

Chisholm agreed with Mr Clare’s comments, arguing that removing the two out of

three rule would reduce diversity as it would result in further media

concentration.[56]

They believed it was ‘ill-advised’ to remove the rule when Australia's media is

amongst the most concentrated in the world and when traditional

media—newspapers, commercial television and commercial radio—continue to be the

main source of news and current affairs for Australians, particularly in regional

areas.[57]

The current Shadow Minister for

Communications, Michelle Rowlands, has iterated this view saying:

Labor’s position on the two out of three

rule has been crystal clear since November 2016 and is evidence-based. There is

no gamesmanship in Labor standing up for the public interest, and our

democracy, by limiting the ability of dominant media voices to consolidate even

further in Australia’s already heavily concentrated media market.[58]

In the debates on this Bill in the House

of Representatives Ms Rowland elaborated further on Labor’s concerns for

diversity:

The majority of the top 10 news websites

accessed by Australians are either directly or jointly owned by traditional

media platforms—meaning that they are the same voices on different platforms.

And the digital divide means that access to new media still remains out of

reach for many Australians, given the substandard levels of broadband

connectivity particularly in rural and regional areas.

While Labor acknowledges the increasing

influence of new media in Australia, we do not mistake the entry of new voices

online or the abundance of online content for diversity in terms of diversity

of ownership of Australian media. It is a mistake to confuse the proliferation

of content for diversity of ownership or opinion.[59]

Labor’s Brian Mitchell continued:

Removing the two-out-of-three rule will

concentrate Australia's media assets in even fewer hands. We have existing

owners demanding that they be allowed to buy each other out so that they can

get bigger, which they say is necessary to better compete on the world stage.

We have a scenario where already-massive media companies want to get even

bigger so that they can face-off against similarly giant companies overseas.

Such a scenario only has one outcome: the swallowing up, buying out and merging

of competitors until, ultimately, only two global entities are left facing off

against each other—and, one day, they themselves will ultimately want to merge.

That is not a future that we should look forward to.[60]

At the same time, Mr Mitchell noted that Labor

supports most of the measures in this Bill, ‘because they are Labor's measures’.

He argued that Labor had ‘led the way on reforming broadcast licence fee

relief, gambling advertising restrictions and funding to support the

broadcasting of women's sport’.[61]

The

Australian Greens

With reference to the first of the 2016 media reform Bills,

the Greens’ Senator Scott Ludlam was of the view that while the Internet has

changed the way Australians engage with media, it should not be an excuse to

change media regulations ‘to suit some of the most powerful media barons in

Australia, the country with the most concentrated media ownership in the world’.[62]

Senator Ludlam considered that it was too easy for the Government to claim that

the Internet ‘has negated the need for any diversity protections’ as the

dominant players in print and broadcast media ‘have successfully used their

incumbency to cement their place at the top of Australia’s online news media

space as well’.[63]

The Senator considered:

We need to make sure new entrants can compete, that existing

players are not so dominant that new voices are crushed. We need to make sure

local content is still being produced, and that Australian stories are still

being told ... Technological advances in streaming services and the like are

being used as a reason to abolish the reach rule, but this only makes sense if

there is a decent national broadband network to deliver these services.[64]

In a dissenting report to the November 2016 Senate inquiry

Senator Larissa Waters stated that the Greens believed that in presenting the

media reform proposed in the 2016 Bills the Government had missed an important

opportunity ‘to progress meaningful reform of the Australian media landscape,

and ha[d] instead settled on a simplistic deregulatory approach that will do

nothing to improve media diversity’.[65]

In May 2017 Senator Ludlam confirmed that the Greens were

concerned about the removal of the two out of three rule as it represented

‘jumping to

the commercial imperative’ without fully considering the public interest.[66]

One Nation, Nick Xenophon Team

and Independents

In July 2016 Senator Hinch was reported

to have said that he had not given the issue of media reform

‘a tremendous amount of thought, but that he would take it “issue by issue” and

get briefings from the relevant ministers’.[67] Twelve months later media reports indicated that Senator

Hinch had ‘no qualms’ about removing the two out of three rule and had ‘thrown

his weight’ behind the revised package in this Bill.[68]

It was speculated in 2016 that Senator Jacqui Lambie could

be supportive if she could be convinced there would be protection ensured for local

news coverage in Tasmania.[69]

It also had previously been reported that Senator Lambie was interested in

ensuring that any media reform contained safeguards to protect local journalism

jobs.[70]

Senator Hanson’s office commented in July 2016 that media

reform and its impact on regional Australians is an area of interest for One

Nation Senators, but that at the time the party did not have a formal policy

position.[71]

One Nation has now been quoted as saying that the two out of three rule is the

main stumbling block for the party. At one point it appeared it supported a

three out of four compromise rule, which was rejected immediately by the media

industry, and no clear proposal was elaborated upon.[72]

In late June 2017, however, the One Nation Whip, Brian Burston, was reported as

stating that the party was ‘rethinking its stance’ and a deal with the Government

‘was possible’.[73]

As Senator Hanson has previously called for more funding for community

broadcasting and protections for local content in Queensland, reports suggest

that One Nation’s support for media changes may depend on the extent to which the

Government is willing to deliver concessions in these areas.[74]

Senator David Leyonhjelm (Liberal Democratic Party) expressed

his support for the previous media reform proposals and is likely to support this

Bill, as is Senator Cory Bernardi.[75]

With regards to the first 2016 Bill, Independent Senator

from South Australia, Nick Xenophon, commented that he would participate in the

Senate inquiry process before deciding his position on the reforms proposed.

Senator Xenophon added that he would like to see licence fees slashed and local

television producers given more generous tax offsets and the revenue loss that

this would incur could be recovered by ensuring that companies such as Netflix,

Google and Apple ‘were paying their fair share of tax’.[76]

In the 45th Parliament Senator Xenophon leads the Nick

Xenophon Team (NXT) of three senators and the NXT also has one member in the

House of Representatives. In conjunction with debates on the second 2016 Bill Senator

Xenophon agreed with industry advocates that free-to-air regional broadcasters

operate in an environment where they pay high licence fees and where

advertising revenue is declining. [77]

The Senator argued for a more level playing field, suggesting

that companies such as Google, Facebook and Netflix should be ‘taxed on a

turnover basis’ and the revenue gained could be used to offset the

‘disproportionately harsh cuts’ which community radio and community television

have suffered.[78]

In September 2016 there were also reports

that Senator Xenophon had ‘struck a deal’ in relation to aspects of

gambling reform in exchange for his support for the second 2016 Bill and that

he had called for anti-siphoning changes to be include in the Bill, but

Minister Fifield denied that the government had agreed to these concessions.[79]

With regards to this Bill, a

number of reports have indicated that because of the continued opposition from

Labor and the Greens that it will not pass through the Senate without the

support of ten of the 12 remaining senators, and that the support of the NXT is

crucial to its passage.[80]

At the commencement of the Parliament’s winter break Senator Xenophon vowed to

use the break to try to resolve the ‘stalemate’ over the Bill and in early July

he and his colleague, Senator Stirling Griff, presented a package of compromise

to the Government. The package reportedly included ‘a tax on Facebook and

Google and tax breaks for smaller and regional publications’.[81]

Position of major interest

groups

Industry

Previous comment

In 2013, in conjunction with the Labor Government’s

attempt to reform media legislation, a Senate Committee investigated the 75 per

cent reach rule and concluded that it was irrelevant in the modern media

environment. The Committee recommended removal of the rule, but added that this

should be on the condition that either legislation or legally enforceable

undertakings were in place to safeguard the delivery of local content for regional

Australia.[82]

At the time of this investigation most broadcasters argued

that the rule was out of date, and that removing it would mean that regulations

were more consistent with converging media technologies. In addition, if the

rule were removed, regional networks and metropolitan networks would be allowed

to merge and this would increase industry efficiency and economies of scale (see

a snapshot of current major media interests in Appendix A).[83]

The WIN and Ten Networks in particular expressed some doubt that rescinding the

reach rule would be as beneficial as most of their fellow broadcasters

believed. [84]

WIN, for example, voiced concern that the end of the rule could mean the end of

local content on regional stations.[85]

WIN later changed its opinion, and its

submission to the Senate inquiry into the 2016 media reform proposals argued

that not only is it the case that pay television can reach 100 per cent of the

population, but the Seven, Nine and Ten networks are able to do so through

their regional affiliates.[86]

In addition, WIN considered the ABC and SBS, as ‘direct competitors’ for

viewers and SBS a competitor for revenue. WIN therefore:

... question[ed] why a government

broadcaster is free to compete for regional advertising revenue whilst not

being constrained by the 75% audience reach rule and also not being required to

work to the local content obligations that apply to regional broadcasters.[87]

The broadcaster added:

Online broadcasters such as Netflix, Foxtel Go, Stan, Presto,

Quickflix, ABC iView, SBS on Demand, Ten Play, 9 Now, Plus 7, Fetch TV, Hulu,

Google, YouTube and any other online media group in Australia, and for that

matter the world, is able to broadcast their content to 100% of the population

whilst Australian commercial television networks are constrained from gaining

scale by the 75% Reach Rule.

Perhaps the most telling example of the redundancy of the

Reach Rule is the recent action of Seven West Media and more recently Nine

Entertainment Co in streaming their channels into regional Australia,

effectively bypassing the Reach Rule. Regional Broadcasters pay a large

percentage of their gross revenue to these Metropolitan broadcasters for the

right to broadcast the programming and are being forced to compete with their

own product suppliers for viewers and for revenue.

WIN, along with the other independent regional broadcasters

have together argued that the abolition of the 75% audience Reach Rule will

give regional broadcasters the ability to find opportunities through which to

gain scale, either through acquisition, merger, partnering with, in a material

fashion or selling into, a Metro Broadcaster. All of these options lead to the

gaining of scale for television networks and create the opportunity to remove

unnecessary or duplicated costs in non-generating content areas of television

businesses and allowing the regional division of the up scaled business. The

result being a greater opportunity to continue with the current investment into

local content and support in regional communities.[88]

In 2015 Fairfax’s Nick Falloon commented that media

ownership changes, such as are proposed in this Bill, will correct what he

called ‘an imperfect market’ which ‘gives unregulated overseas players a

complete free hand’.[89]

In early 2016 Fairfax Group’s Chief Executive, Greg Hywood, stressed the point

that a level playing field was what Fairfax wanted and he insisted that the

Group was not interested in buying a television network, despite any changes to

regulations as:

... it could produce as much video as it wanted across its

websites and the ‘notion of scale in advertising between print and TV is not remotely

as powerful’, thanks to the digital revolution ...

“We're very supportive of operating in a deregulated,

unregulated environment because it just provide optionality [sic] and we should

have optionality because the major competitors in our advertising are not

having to deal in a regulated environment at all.”[90]

News Corp Australia, was more cautious in

its support, but nevertheless it labelled the proposals as ‘a step towards

media reform.’[91]

It could be argued that at the time News Corp’s caution was prompted by its

failure to convince Minister Fifield to consider including proposals to amend

the anti-siphoning scheme.[92]

Foxtel, which is 50 per cent owned by News Corp, also did not support the

repeal of media ownership and control rules unless that repeal occurred in

conjunction with reform of the anti-siphoning regime.[93]

Re-introduction of reform proposal

The Ten Network welcomed the

re-introduction of the second 2016 media Bill and called on the Parliament to

pass it ‘as a matter of urgency’.[94]

Ten Network chief executive officer Paul Anderson urged Parliament to support Australian

media companies that are investing in local content and local jobs by passing

the legislation. According to Mr Anderson, unless the Bill passed ‘our big tech

competitors [will continue to get] a free ride by strangling local media companies’.[95] In response to concerns

raised about removing the two out of three rule Mr Anderson added that he

had heard no rational argument in favour of its retention; it was ‘illogical

and antiquated and threatens local diversity by constraining Australian media

companies in our efforts to grow and compete’. The Ten Network officer was

‘disappointed’ that there was to be another inquiry into the reform proposals.[96]

News Corp Australia welcomed the introduction

of the second Bill into the Parliament and supported its passage, as did WIN

Network Chief Executive Officer, Andrew Lancaster, who saw the legislation as

‘pivotal’ for ensuring Australian companies are able to compete with

‘foreign-owned tech companies’.[97]

The Chairman of Prime Media Group, John Hartigan, called upon all

Parliamentarians to support the reforms in the Bill and warned that if they

were not passed ‘the Federal parliamentarians who chose to stand in the way of

reform need to be prepared to accept the blame for less diversity, the value erosion

of Australian media companies and the loss of hundreds of jobs’.[98] Grant Blackley, CEO

Southern Cross Austereo, added his support for the legislation and stressed his

view that rules put in place in the days before the Internet, pay TV, Google,

Facebook and YouTube ‘have no place in today’s media landscape and are holding

back regional media businesses’.[99]

These comments supplement those made to

the Senate Committee inquiry into the earlier version of this Bill and

re-stress the arguments that commercial media, in particular regional

commercial media, are undergoing 'significant structural challenges', including

the loss of advertising markets to online platforms.[100]

Prime Media, for example, noted that regional television had suffered falls in

advertising revenue of $65.0 million in the three- year-period prior to 2016.[101]

The 2017

Bill

When Minister Fifield announced prior to the 2017–18 Budget

that broadcasting licence fees would be abolished for commercial free-to-air

broadcasters, and this commitment was confirmed in the Budget, the industry

bodies Commercial Radio Australia and Free TV Australia welcomed the

announcement.[102]

Free TV saw the change as ‘crucial’ for Australian jobs and for the industry’s

‘ability to continue creating great local programming that is watched by

millions of Australians every day’.[103]

At the time the Government noted

that it would set a price on the use of radiofrequency spectrum that it argued

would more accurately reflect its use and that this would give commercial broadcasters

‘flexibility to grow and adapt in the changing media landscape, invest in their

businesses and in Australian content, and better compete with online providers’.[104] In addition, the licence fee relief would make it

possible for the Government to deliver ‘a community dividend’ in the form of

gambling restrictions.[105]

The Broadcasting and Content Reform package announced by Minister Fifield was

also to enhance proposals in the two previous media reform Bills by including changes

to anti-siphoning rules to allow pay television operators more opportunity to

bid for major sporting events.[106]

As the Parliamentary Library’s analysis of the 2017–18 Budget

noted, it appeared significant concessions were made in developing this broadcasting

and content reform package.[107]

For example, as noted earlier in this Digest, free‑to‑air

broadcasters and subscription television operators have for many years taken

uncompromising stances on the anti-siphoning list, with the former opposed to

change. However, the representative bodies for both these media sectors from

the outset praised the 2017 proposals.[108]

According to the ASTRA, such support resulted from the involvement of ‘the

entire media industry in the development reforms that address the broad

concerns of all participants’.[109]

In the last week of May 2017 media industry leaders addressed

a Government-organised summit in Canberra to attempt to persuade crossbench

senators to support the new media package as presented in this Bill. The

leaders included News Corp’s Michael Miller, Seven West Media’s Tim Worner,

Fairfax Media’s Greg Hywood, Foxtel’s Peter Tonagh and Macquarie Media’s Adam

Lang in what was touted as a ‘rare display of pan-industry support’ for change.[110]

Prior to the summit, Michael Miller urged the Senate to pass the entire media

package ‘to ensure the future viability of the sector’. He argued also that

only ‘holistic and complete reform’ would support local media voices.[111]

Following the Bill’s successful passage through the

House of Representatives, industry spokespersons expressed disappointment that

it did not pass in the Senate before the winter break for the Parliament, but

sources noted that it was better to defer the legislation if it meant the

legislation would eventually succeed. Importantly, one spokesperson warned that

unless the whole package was passed, internal industry agreement could not be

guaranteed, stating that if there were ‘any cherry picking or an attempt to

pull [the proposals in the Bill] apart then the deal’s off from the sector’s point

of view’.[112]

Media and other commentators

Criticism of changes to media regulation

In 2014 Ben Eltham in the New Matilda asked what deregulation in general would mean for Australia’s

media and for democracy and concluded that the result would be media

consolidation ‘and a further weakening of diversity in the Australian mediascape’.[113] Mr Eltham’s 2016

assessment was that, while the Government says that local content will continue

to be protected if changes are made to media ownership restrictions, ‘Australian

citizens that rely on journalists to gather and report the news so they can

make informed decisions about our democracy may beg to differ’.[114]

The efficiencies that will be inevitable as media companies merge will mean job

losses and fewer, larger media companies will control fewer media voices. In Mr

Eltham’s view, this will also mean there will be fewer journalists to report

and investigate.[115]

Crikey commentators Bernard Keane and Glenn Dyer also

discussed media changes in an article in 2014. In relation to the possible

removal of the two out of three rule, Keane and Dyer considered the only

substantial beneficiary would be News Corp, as this international media giant

would then be able to take control of the Ten Network and have the potential to

increase its influence over Australian audiences. In Keane and Dyer’s opinion,

this was because:

[d]espite a fragmenting media landscape,

there’s still nothing more politically influential in Australia than a TV

network, which is one of the last places where hundreds of thousands of

Australians still gather to be told what’s going on.[116]

Commenting on the announcement of the media package reflected

in the current Bill, Dyer and Keane were sceptical of the extent to which

traditional media can realistically be assisted to cope with the new media

environment. They saw the overall package as ‘aid’ for an industry ‘up against

an unstoppable wave of change’ and argued that licence fee cuts and/or any

media mergers or takeovers that may result from removing legislative

restrictions will not halt that change.[117]

In Dyer and Keane’s opinion, Google and Facebook will continue to undermine

other forms of media and ‘care packages’ will not be able to save ‘media

dinosaurs’.[118]

Keane and Dyer have argued also that media changes should

not proceed while questions remain about the circumstances surrounding Network

TEN being placed in administration. They ask for clarification of a number of

issues, including what was the role of Lachlan Murdoch, 21st Century Fox and

Bruce Gordon and conclude that until there are clear answers:

... any decision by parliamentarians about the media reform

Bill may be undertaken with at best an incomplete understanding of the facts;

possibly, they may have been actively misled. And if the Bill is passed, that

passage will always be clouded by questions of whether the entire political

process was gamed.[119]

In his 2016 commentary on the previous reform proposals academic

Vincent O’Donnell maintained that they did not represent reform; they were

instead:

... a capitulation to the interests of licensees,

shareholders and rent-seekers in the Australian media industries, painted up in

the gaudy raiment of the protection of the public interest.[120]

In relation to local content measures in

previous Bills, and which are also a feature of this Bill, Mr O’Donnell

continued:

[t]he proposed changes to the points system,

which deals with the number of news stories relating to ‘local’ areas, seeks to

support diversity. But like so much government regulation, conscientiously

planned by those with little experience of the industry it will affect, it will

be easy to meet the target without honouring the purpose.

Story selection, buying in copy, sourcing

amateur footage from mobile phones and using uncorroborated eyewitness accounts

are among the many ways of covering the surface of events without providing the

depth that serious news journalism demands.[121]

Others who have expressed similar concern

include Associate Professor Tim Dwyer from the University of Sydney who in

2016 said that, should the two out of three measure become law, there will be

an inevitable reduction in the news sources people need to access a wide range

of points view.[122]

More recently Professor Dwyer has argued that removing the two out of three

rule, ‘the last major remaining bulwark’ is not the solution to media concentration;

removal will only make Australia’s media more concentrated in Rupert Murdoch’s hands.[123]

Professor Dwyer argues:

... Australia needs to have a comprehensive review of how news

is now consumed across online and traditional media. This would serve as a

precursor to media diversity policies that tackle the changing news environment

... The media reform package smacks of the government doing deals with the

incumbent commercial TV networks and News Corp’s Foxtel. It is a short-sighted

political play, and not a serious attempt to tackle structural change in the

media industries by looking at ways to maximise diversity for audiences.[124]

Professor Michael Fraser from the University of Technology

Sydney has also argued that ‘it is important to maintain the media ownership

laws we have to ensure diversity in the mainstream media’.[125]

Denis Muller from the University of Melbourne has contended that while

the two out of three and 75 per cent reach rules this Bill proposes to rescind

are ‘unenforceable’ and ‘mocked’ by digitisation, the underlying rationale for

them remains valid.[126]

Dr Muller believes that it is ‘in the public interest to have a diversity of

voices in the news media and some restraints on the concentration of media

power’. He has maintained that while

[t]heoretically, digital technology enables

everyone with a computer, access to the internet and the skills of basic

literacy to become a publisher. A few new players have emerged as a result,

most notably Crikey and The Guardian Australia, but the

overwhelming majority of people who get their news online get it from the

long-established media organisations – the ABC, News Corp and Fairfax.

The reason is that even with the heavy cuts to

journalists’ jobs, these organisations still have more resources, more access

to newsmakers, a bigger news-making capability and stronger reputations than

most start-ups.

If the mooted rule changes go through, the mergers

already foreshadowed by the media industry will mean less diversity – not more.[127]

Support for change

ACCC Chairman, Rod Sims, has criticised current media

legislation as obsolete and ‘possibly protectionist’. According to Mr Sims, the

reach rule potentially limits competition and efficient investment in the media

industry, while the two out of three rule may be preventing the efficient

delivery of content over multiple platforms.[128]

In addressing the concerns expressed by commentators such as Bernard Keane and Glenn

Dyer about a possible News Corp takeover of the TEN Network as a result of

change, Mr Sims has also commented that section 50 of the Competition and

Consumer Act 2010 prohibits any deal that would have the effect, or likely

effect, of substantially lessening competition.[129]

Senior Lecturer in

Political Science at the University of Canberra, Michael de Percy, has argued

that it is a contentious point whether localism (a term which includes both the

provision of local content by regional broadcasters and the local ownership of

those broadcasters) has ever existed in Australia in the first place. Dr de

Percy sees localism as ‘much more than simply requiring

commercial television stations to provide local news services’.[130] In his opinion, the broadband services that now

exist enable greater consumer participation in news media production and social

networks transform ‘traditional top-down localism of television programming to

a more participatory localism driven by consumers’.[131]

Dr de Percy is of the view that this has eroded the relevance of

Australia’s cross-ownership laws. In such an environment:

... [continuing to place] restrictions on

cross-media ownership where the distinction no longer exists is hardly the

recipe for a commercially viable and internationally competitive communications

industry. Ideas about localism need to change too if the advantages of

reconvergence are to be realised by Australian media companies. Indeed,

regulating for localism may well benefit overseas competitors rather than the

people it was designed to serve.[132]

An editorial in The Australian argued in 2014 that

the removal of cross-media ownership law may be the way that local content

offerings can be improved for regional areas because a proprietor who owns television,

radio, print and Internet assets in an area ‘could deepen and expand local

content and news’.[133]

In a similar vein Chris Berg from the Institute of Public Affairs argued that ‘it

is possible that local content requirements are crowding out alternative

entrepreneurs’ who may be better able to produce local content.[134]

In his critique of the first media reform

Bill, Dr Derek Wilding from the University of Technology Sydney considered

the media changes suggested represented ‘a media landscape that is worth

supporting’.[135]

Dr Wilding was in favour of repealing the 75 per cent rule and the

two out of three rule if it helped ‘support the transition of print media

companies into converged news gathering organisations in a landscape where we

have at least three strong local commercial players’.[136]

His proviso for supporting this situation was, however, that there needed to be

an assurance of ‘reasonable standards of practice’ such as accuracy, fairness,

transparency and respect for privacy.[137]

He concluded:

If the number of independent sources of information is

reduced, whether through market forces or legislative change, then in my view

it becomes more important that those players are committed to appropriate

industry based standards of accuracy and fairness in reporting. It is also

appropriate that, in a regulatory environment permitting cross-media ownership,

those standards apply across media platforms.[138]

Audiences

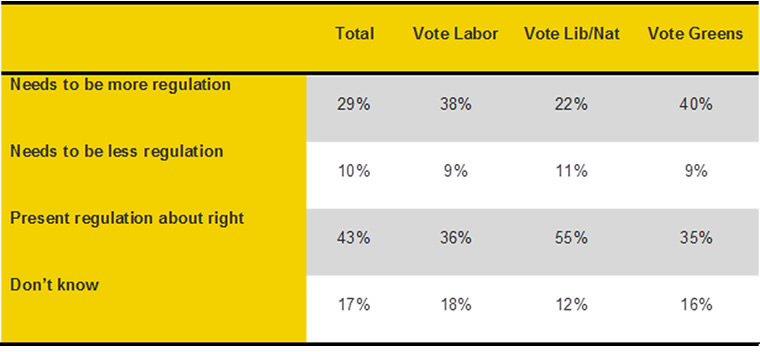

Audience views of changes to media regulation can reflect

the types of questions asked in surveys. For example, in 2013 Essential Report

research found that most voters were not overly enthusiastic about removing

media regulation. The majority of those surveyed by Essential believed that

media regulation was either ‘about right’ or that there needed to be more

regulation (see Figure 2 below).[139]

A later survey of regional audiences by JWS

Research for the Australian Financial Review in 2015 concluded that

there was almost equal support for retention of the media regulation and

changing the rules (see Figure 3 below). The interesting finding from this

latter survey was that people were very supportive of rule changes if they

thought that these would ensure they continued to receive local news.[140]

Figure 2: 2013: satisfaction with media regulation

Source: Essential Report[141]

Figure

3: 2015: audience opinion of media reform

Source: Australian

Financial Review[142]

Financial

implications

As noted in the Explanatory Memorandum to this Bill, the

provisions in Schedule 5 of this Bill will result in an estimated revenue loss

of $417.7 million in the period 2017–18 to 2020–21.[143]

Some of this revenue will be recovered through the proposed new tax imposed

under the Commercial Broadcasting (Tax) Bill 2017. This is expected to

deliver an estimated $43.5 million per annum.[144]

However, payments to assist broadcasters affected by the

transitional transmitter licence arrangements will also cost the Government.

These payments are estimated at approximately $18.4 million for the period to 2020– 21.[145]

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed the

Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or declared

in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The

Government considers that the Bill is compatible.[146]

With regards to the local content obligations proposed,

there may be some question about the extent to which broadcasters would be able

to deliver local content to the satisfaction of all constituencies within each

area within the limited time frames that will be introduced under this Bill—albeit

arguably, they are an improvement on the existing local content.

On Line Opinion commentator David Vadori made the

following observations with regards to how the rights of audiences may be

affected by the proposals in the September 2016 Bill and similar arguments

would apply with regards to this Bill:

The democratic ideal of a media which is impartial, and

designed to inform citizens, is inevitably compromised as media ownership

becomes more concentrated. Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human

Rights unequivocally states that everyone has the inalienable right ‘to

hold opinions without interference...’ However this right is undermined as

media ownership becomes more concentrated and the number of proprietors is

reduced.

Concentration of media ownership is frequently seen as a

problem of contemporary media and society. The fundamental threat that

concentrated media poses to any society is that, as the influence of privately

funded media increases, the democratic capacity of the media as an instrument

to inform and educate citizens is diminished. This is due to a reduction in the

number of perspectives that are available to citizens on any given issue, at

any given time; and this interferes with an individual's ability to formulate

an opinion, as access to information presented in an unbiased and balanced

fashion becomes more and more restricted. In Australia, this problem is

markedly more acute than elsewhere in the world and thus governments should

strive to ensure that the Australian media is impartial and informative.[147]

Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Human Rights

The Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human rights did not

consider that either of the previous Bills raised human rights concerns.[148]

At the time of writing, it has not commented on this Bill, which on 21 June it

deferred for consideration at a later date.[149]

Key issues and provisions

Schedule 1

Schedule 1 of the Bill proposes to repeal the sections of

the BSA which set out the conditions of the 75 per cent reach rule.

Subsections 53(1) and 55(1) and (2) of the BSA set out this rule which prevents

a person, either as an individual or as a director of one or more companies,

from being in a position to exercise control over commercial television

broadcasting licences whose combined licence area populations exceed 75 per

cent of the population of Australia.[150]

Schedule 2

Schedule 2 of the Bill proposes to repeal the two out of

three cross-media control rule which is set out in section 61AEA and

subdivision BA of Division 5A of Part 5 of the BSA. The two out of three

rule prohibits a person controlling more than two out of three regulated media

platforms (that is, a commercial television broadcasting licence, a commercial

radio broadcasting licence and an associated newspaper) in any one commercial

radio licence area.

Items 1 to 3 of this Schedule propose to

repeal the definition of unacceptable three-way control situation and the

prohibition on media business transactions which may lead to a

three-way-control situation. The other items in this Schedule are either

consequential to the repeal of the two out of three rule or are technical

amendments.

Schedule 3: Part 1

Box 2: definitions

|

Aggregated markets:

aggregated markets came into being in the 1980s. Aggregation involved creating

larger regional television markets by combining certain existing licence areas

in the well-populated eastern states so that the combined areas could be served

by three commercial services. The rationale for aggregation was that larger

service areas would provide an opportunity for licensees to expand and develop

regional content and that the preferences of viewers would provide an incentive

for regional licensees to produce local programs.[151] The current aggregated markets are listed in the definitions at proposed section

61CU of the BSA, at item 1 of Schedule 3 to the Bill.

These are: Northern New South Wales, Southern New South Wales, Regional

Victoria, Eastern Victoria, Western Victoria, Regional Queensland and Tasmania.

Non-aggregated markets:

non-aggregated markets are those that have been considered to be too widespread geographically and which do not have the population

to support three competing commercial television services.[152] These are listed

in proposed section 61CU. They are: Broken Hill, Darwin,

Geraldton, Griffith and the Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area, Kalgoorlie,

Mildura/Sunraysia, Mount Gambier/South East, Mt Isa, Remote and Regional

Western Australia, Riverland, South West and Great Southern and Spencer Gulf.

Trigger event: proposed

section 61CV of the BSA will define a trigger event for a regional

commercial television broadcasting licence as: occurring when a person starts

to be in a position to exercise control of a commercial television broadcasting

licence, and immediately after that event, is in a position to control two or

more television broadcasting licences (including at least one regional

commercial television licence) with a combined licence area population that

exceeds 75 per cent of the population of Australia.

Material of local

significance: proposed section 61CU intends that material of local

significance will be defined in a local programming determination. Proposed section 61CZ provides that the ACMA will make the local programming

determination. The determination will deal with issues such as: what areas

will be designated local areas ‘in relation to’ a regional commercial

television licence, what constitutes material of local significance for a local

area and what is required for news reports to receive three points towards

quota points.[153]

|

Item 1 of Schedule 3 proposes to insert a new

Division (Division 5D) into Part 5 of the BSA. Commercial

television broadcasters who broadcast in aggregated markets and who are

affected by a trigger event will be required to broadcast to local areas

material of local significance in order to accumulate at least 900 points in

each timing period (with at least 120 points being broadcast each week) that

commences six months after the trigger event occurs (proposed subsection

61CW(1)). A timing period is six weeks.[154]

In the six month transitional period the broadcaster will be

required to broadcast 720 minutes of local content (with at least 90 points

broadcast each week) (proposed subsection 61CW(2)). There is no

change in the local content broadcasting requirements for broadcasters who are

not affected by a trigger event (proposed subsection 61CW(3)).[155]

New subsection 61CX also proposes to introduce local

programming requirements for non-aggregated markets if a trigger

event occurs. The broadcaster will be required to broadcast to each local

area material of local significance to accumulate 360 points (with at least 45

points being broadcast each week) in each timing period that commences six

months after the trigger event occurs. The proposed subsection does not

apply to licences granted under sections 38A and 38B of the BSA.[156]

Proposed section 61CZA requires licencees who have

experienced a trigger event to produce and retain (for 30 days after

each six week timing period or longer if ACMA requires) an audio visual record

of the material of local significance it has broadcast in local areas. The

record must be provided to ACMA on request.

In addition, proposed section 61CZB proposes

that licencees subject to trigger events must provide ACMA with two

compliance reports. The first of these is to cover a 12-month period commencing

six months after the trigger event and the second report to cover the

12-month period after the first report period.

Box 3: the points system—definitions and allocations

|

Under proposed section

61CY:

Eligible period: it

is intended that points will be able to be accumulated in the hours from 6.30 am

to midnight Monday to Friday and 8am to midnight on Saturday and Sunday (proposed subsection 61CY(1)).

Timing period: it is

intended that points will be calculated during certain timing periods. Proposed

subsection 61CY(2)) designates these timing periods as:

- the period starting on the

first Sunday in February each year and continuing for six week periods until

the end of the 42nd week after this date. Points can be accumulated in this

period

- the period starting at the

end of the 42nd week after the first Sunday in February and ending immediately

before the first Sunday in February the following year. (Points cannot be

accumulated during certain parts of this period—see proposed subsection

61CY(4)).

Under proposed subsections 61CY(9) and (10) it is proposed through the local programming

determination that ACMA may be able to vary the timing periods for individual

non-aggregated licensees.

|

Box 4: the points system—points allocations : proposed

subsection 61CY(3)

|

Item

|

Material

|

Points for each minute of material

|

|

1

|

News that:

(a) is broadcast during an eligible period by a licensee covered by

subsection 61CW(1) or 61CX(1); and

(b) has not previously been broadcast to the local area

during an eligible period; and

(c) depicts people, places or things in the local area;

and

(d) meets such other requirements (if any) as are set out in the

local programming determination.

|

3

|

|

2

|

News that:

(a) is broadcast during an eligible period; and

(b) has not previously been broadcast to the local area during an

eligible period; and

(c) relates directly to the local area; and

(d) is not covered by item 1.

|

2

|

|

3

|

Other material that:

(a) is broadcast during an eligible period; and

(b) except in the case of a community service announcement—has not

previously been broadcast to the local area during an eligible period; and

(c) relates directly to the local area.

|

1

|

|

4

|

News that:

(a) is broadcast during an eligible period; and

(b) has not previously been broadcast to the local area during an

eligible period; and

(c) relates directly to the licensee’s licence area.

|

1

|

|

5

|

Other material that:

(a) is broadcast during an eligible period; and

(b) except in the case of a community service announcement—has not

previously been broadcast to the local area during an eligible period; and

(c) relates directly to the licensee’s licence area.

|

1

|

Proposed subsections 61CY(5) and (6) place

limitations on the material that is able to be used towards accumulating

points. These subsections intend that material which relates to an overall licence

area (or in the case of the Regional Victoria licence areas 104 and 106, to the

combined areas) can accumulate no more than 50 per cent of the points required

under the legislation.

Further limitations apply to the number of community

service announcements that can be broadcast to accumulate points. Under proposed

subsection 61CY(7) the first broadcast of a community service

announcement (and four repeats of that announcement) are eligible to accrue

points. In addition, no more than ten per cent of points accumulated in a local

area in a timing period can be community service announcements (proposed

subsection 61CY(8)).

Box 5: ACMA and the Minister

|

Proposed subsection

61CZC will require ACMA to review the new Division 5D, the licence

conditions in paragraph 7(2)(ba) of Schedule 2 of the BSA (see below)

and the local programming determination and provide a report to the Minister on

its findings.

It is intended that the

Minister will be able to direct ACMA about the exercise of the powers conferred

on it by Division 5D (other than the review and reporting requirements in proposed

subsection 61CZC) and that ACMA must comply with these directions (section

61CZD).

Item 2 of Schedule

3 to the Bill proposes to impose a new licence condition in Schedule 2 of the BSA.

This will be imposed under proposed paragraph 7(2)(ba) and will require

all commercial television broadcasting licences to comply with the applicable

local programming requirements.

|

Schedule 3: Part 2

Item 3 proposes to repeal section 43A of the BSA

which sets out the current requirements for regional aggregated commercial

television broadcasting licences to provide material of local significance. The

repeal of this section is to take place six months after this Bill receives

Royal Assent.

Item 4 provides that ACMA is taken, six months

after the Bill receives Royal Assent, to have revoked the Broadcasting

Services (Additional Television Licence Condition) Notice 2014, which

currently sets out the detail of the local content condition.[157]

The requirements in subsections 43(2) and 43(3) of the BSA do not

apply to the revocation.[158]

However, the Notice continues to apply with regards to material broadcast

during a timing period that commenced before the revocation is taken to have

occurred.

Schedule 4

Schedule 4 deals with the anti-siphoning list, which sets

out a list of events that the Minister considers should be available on

free-to-air television. Item 1 of Schedule 4 amends subsection 115(1AA)

of the BSA which currently states that events are removed from the

anti-siphoning list and available for subscription television providers to

purchase 12 weeks before the event commences. It is proposed that events on the

anti-siphoning list will be delisted 26 weeks before they commence.

Items 5 to 8 propose to repeal clauses in the BSA

which restrict commercial television and national broadcasters (the ABC and

SBS) from televising an event listed on the anti-siphoning list on a secondary

channel unless the broadcasters have previously televised the event on their

primary service or they will television the event simultaneously on their

primary and secondary services.

Item 9 repeals the Schedule to the Broadcasting Services

Events Notice (No. 1) 2010 which contains the list of events that compromises

the anti-siphoning list.[159]

This list is specified by the Minister under subsection 115(1) of the BSA.

The item intends to replace the current list with the one shown below in Box 7.

Box 7: proposed anti-siphoning list

|

Olympic Games

- Each

event held as part of the Summer Olympic Games, including the Opening Ceremony