Bills Digest No. 101, 2016–17

PDF version [678KB]

Damon Muller

Politics and Public Administration Section

26

May 2017

Contents

The Bills Digest at a glance

Purpose of the Bill

Structure of the Bill

Background

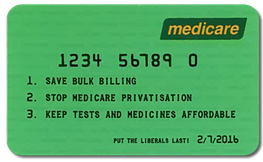

Figure 1: the fake Medicare card

handed out by unions

Committee consideration

Joint Standing Committee on Electoral

Matters

Senate Standing Committee for the

Scrutiny of Bills

Policy position of non-government

parties/independents

Position of major interest groups

Financial implications

Statement of Compatibility with Human

Rights

Parliamentary Joint

Committee on Human Rights

Key issues and provisions

Authorisation of electoral material

Electoral matter

Disclosure entities

Authorisation

How-to-vote cards

Electoral Commissioner’s

determination

Investigations and injunctions in

relation to authorisations

Potential issues with enforcement

Impersonating a Commonwealth body

Other provisions

Concluding comments

Date introduced: 30

March 2017

House: House of

Representatives

Portfolio: Special

Minister of State

Commencement: Section

1 to 3 and Schedule 2 commence the day after Royal Assent. Schedule 1

commences the day after six months after Royal Assent.

Links: The links to the Bill,

its Explanatory Memorandum and second reading speech can be found on the

Bill’s home page, or through the Australian

Parliament website.

When Bills have been passed and have received Royal Assent,

they become Acts, which can be found at the Federal Register of Legislation

website.

All hyperlinks in this Bills Digest are correct as

at May 2017.

The Bills Digest at a glance

- The

Electoral and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2017 (the Bill) implements a

comprehensive scheme for regulating the authorisation of electoral

communication for federal elections and referendums (Schedule 1), and

creates an offence criminalising impersonating a Commonwealth body (Schedule

2). The Bill seeks to address campaigning strategies such as the use of

bulk voice and text messages as was seen in the 2016 federal election.

- The

Bill implements a new electoral matter authorisation regime that covers a broader

range of types of election communication than the existing requirements. It

includes a table to clearly define the material which must carry information

regarding its source and authorisation, what information it must carry and

provides specific requirements for certain types of material (such as printed

material) and certain types of entities (such as political parties, associated

entities and political donors). The proposed requirements explicitly cover bulk

text messages and voice messages, and have exceptions for certain types of

communications (printing on clothing, reporting of news and satire, for

example).

- Certain

types of individuals and organisations undertaking electoral communication,

such as political donors, and certain types of communication, such as bulk text

messages, which did not require provision of authorisation details under the

existing arrangements will require authorisation under the proposed provisions

of the Bill.

- The

Bill further provides for the Electoral Commissioner to issue a disallowable

legislative instrument to specify details of the authorisation requirements.

- The

Bill would make breaches of the new authorisation requirements a civil offence

enforceable under the Regulatory Powers (Standard Provisions) Act 2014, carrying

a civil penalty of 120 penalty units (currently $21,600) for an individual. The

Bill would require the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) to investigate and

enforce breaches of the authorisation requirements, and provides investigative

powers to the AEC to obtain and retain information and documents in its

investigations of these breaches. It would also expand the existing powers to

impose injunctions to include carriage service providers in relation to bulk

voice calls and text messages.

- The

changes to the authorisation requirements for electoral matter in the Bill are

essentially identical for the two main pieces of electoral legislation, the Commonwealth

Electoral Act 1918 and the Referendum (Machinery Provisions) Act 1984.

- The

Bill would amend broadcasting legislation covering the public and commercial

broadcasters to require broadcasters to collect the information required to be

broadcast with electoral matter, and oblige them to take steps to ensure the

correct details are broadcast.

- The

Bill amends the Criminal Code Act 1995 to create the offence of ‘false

representations in relation to a Commonwealth body’, carrying a maximum penalty

of imprisonment for two years. The offence is similar to that of impersonating

a Commonwealth official, though is not focused on a specific individual, and

applies regardless of whether the body being impersonated exists.

Purpose of

the Bill

The purpose of the Electoral and Other Legislation

Amendment Bill 2017 (the Bill) is to amend the Commonwealth Electoral Act

1918[1]

(CEA) and the Referendum (Machinery Provisions) Act 1984[2]

(RMPA) (collectively, the electoral legislation) to:

- extend

the current requirements for authorisation of electoral material to cover all

electoral material, including bulk text messages, bulk voice calls, and

internet advertisements

- to

provide procedures for investigations of and injunctions against entities that contravene

those requirements and

- to

amend the Criminal Code Act 1995[3]

to create a new offence of ‘false representations in relation to a Commonwealth

body’.

The Bill also amends the Australian Broadcasting

Corporation Act 1983,[4]

the Broadcasting Services Act 1992,[5]

the Parliamentary Proceedings Broadcasting Act 1946[6]

and the Special Broadcasting Service Act 1991[7]

(collectively, the broadcasting legislation) to collect the required

particulars for the broadcasting of electoral material and to include the

requirement to announce authorisations of electoral material where required by

the CEA and RMPA.

Structure

of the Bill

The Bill is presented in two Schedules.

Schedule 1 has two parts, and commences the day

after six months from when the Act receives Royal Assent.

Part 1 includes the amendments to the electoral legislation

to establish the expanded requirements for the authorisation of electoral

material. It establishes the concept of a ‘notifying entity’ that is

responsible for authorising specific electoral communication, lists the

required particulars to be included for specific classes of political

communication, and provides civil penalties for failing to properly authorise

electoral material. It further provides powers to the Australian Electoral

Commission (AEC) to conduct investigations and seek injunctions in relation to

authorisation of electoral material.

Part 2 contains the amendments to the broadcasting Acts

to require broadcasters to collect the required information and broadcast the

appropriate authorisation notices for electoral material.

Schedule 2 creates the new offence of ‘false

representations in relation to a Commonwealth body’ and commences the day after

the Act receives Royal Assent.

Background

One of the pivotal issues of the 2016 Federal Election was

the privatisation of Medicare. In August 2014 the Department of Health had

sought expressions of interest (EOI) for outsourcing the payments functions of

several benefits schemes, including Medicare.[8]

According to the EOI the outsourcing would not have affected the face-to-face

services of Medicare.[9]

As part of its election campaign the opposition Labor Party

claimed that the Coalition Government intended to privatise Medicare. The Prime

Minister denied that the Government was planning to privatise Medicare, and

gave a commitment that ‘every element of Medicare’s services will continue to

be delivered by government. Full stop’.[10]

Despite the Prime Minister’s denials, veteran political commentator Paul

Bongiorno noted that ‘the electorate is highly suspicious of the conservatives

in the health space’.[11]

Labor’s Medicare campaign was dubbed ‘Medi-scare’ by the

media, and which was considered responsible for a significant poll boost for

Labor, putting it much closer to an election win, and required the Coalition to

re-focus its campaign to counter the perception that it would privatise

Medicare.[12]

In the days leading up to election day unions handed out

one million cardboard flyers resembling Medicare cards supporting the campaign

(see Figure 1).[13]

The campaign also included bulk broadcasts of mobile phone text messages and

bulk ‘robo-call’ voice messages.

Figure 1: the fake Medicare card handed out by unions

Source: Provided by the National Library of Australia election

ephemera collection.

The voice messages included one message from the president

of the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) and another targeting Malcolm

Turnbull on Medicare that had no indication of its source.[14]

A bulk text message was sent from Labor’s Queensland

office that, according to a report in Crikey, purported to be from

Medicare. The message stated, ‘Mr Turnbull’s plans to privatise Medicare will

take us down the road of no return. Time is running out to Save Medicare.’[15]

The Queensland Labor state secretary, in evidence to the

JSCEM inquiry, stated that Labor had sent the message but that it has not been

intended to be represented as having been sent by Medicare but rather that the

message had a subject line of ‘Medicare’ as it was in relation to Medicare.[16]

The Labor and union movement campaign tactics drew several

comments from the Prime Minister. In his campaign launch speech a week before

the election, Prime Minister Turnbull stated:

Labor believes its best hope of being elected is to have

trade union officials phone frail and elderly Australians in their homes at

night, to scare them into thinking they are about to lose something which has

never been at risk. Bill Shorten put this Medicare lie at the heart of his

election campaign. That’s not an alternative government, that’s an opposition

unfit to govern.[17]

In his election night speech Prime Minister Turnbull

labelled the campaign ‘some of the most systematic, well-funded lies ever

peddled in Australia’.[18]

He stated:

The mass ranks of the union movement and all of their

millions of dollars, telling vulnerable Australians that Medicare was going to

be privatised or sold, frightening people in their bed and even today, even as

voters went to the polls, as you would have seen in the press, there were text

messages being sent to thousands of people across Australia saying that

Medicare was about to be privatised by the Liberal Party.

And the message, the message, the SMS message came from

Medicare. It said it came from Medicare. An extraordinary act of dishonesty. No

doubt the police will investigate. But this is, but this is the scale of the

challenge we faced. And regrettably more than a few people were misled. There’s

no doubt about that.[19]

The SMS message was referred to the Australian Federal

Police by the Government, however, the AFP reportedly found there was no

possibility of prosecution as it was not an offence to imitate a Commonwealth

entity.[20]

The lack of ability to prosecute was reportedly because the message appeared to

come from Medicare as an entity and not from an individual government officer.[21]

A post-election survey by JWS Research found that health

was the most important issue in the campaign, with 57 per cent of respondents

nominating heath as a key vote influencer, including 38 per cent specifying

Medicare specifically. Voters who voted on election day, and those who decided

who they would vote for on election day, were more likely to nominate Medicare

as a vote influencer.[22]

Following the election, the Special Minister of State,

Senator Scott Ryan, asked the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters

(JSCEM) to ‘inquire into and report on all aspects of the 2016 federal election

and related matters’. As part of the terms of reference to the Committee, the

Minister included ‘the application of provisions requiring authorisation of

electoral material to all forms of communication to voters’.[23]

The Committee was asked to provide an interim report on authorisation

requirements for voter communication.

On 9 December 2016, following a number of public hearings,

the Committee released its Interim

Report on the Authorisation of Voter Communication.[24]

The report contained six recommendations. Recommendations 1 to 3 and 5 and 6

related to amending the CEA to explicitly address the authorisation of

electoral material and to make the authorisation requirements clear, concise

and easy to navigate. Recommendation 4 was that the Committee conduct further

inquiry and make recommendations in relation to the issues of impersonating a

Commonwealth officer and a Commonwealth entity. These recommendations are

discussed in more detail under Committee consideration. It was noted in the second

reading speech that the Bill addresses the recommendations in the report.[25]

Committee

consideration

Joint

Standing Committee on Electoral Matters

The Bill was introduced by the Government in response to

recommendations from the JSCEM in its Interim

Report on the Authorisation of Voter Communication of December 2016, as

part of its Inquiry into and report on all aspects of the conduct of the 2016

Federal Election and matters related thereto.[26]

The Bill had not been referred back to the Committee at the time of

publication.

In its report the Committee noted that the existing

requirements for authorisation in the CEA were inadequate to the task of

ensuring transparency and accountability for electoral communication. The

report recommended that a principles based approach be adopted based on

accountability, traceability, and consistency. In addition, the Committee

argued that the CEA should be made more user friendly, and that the

authorisation provisions be brought together in a stand-alone part of the Act

to be clearer and more easily accessible. To further aid in clarifying the

requirements, the Committee recommended that an ‘objects clause’ be inserted

into the Act to list the principles and purpose of the authorisation

requirements.

The Bill adheres closely to the Committee’s

recommendations. The insertion of a new Part to the electoral legislation

dealing explicitly with authorisation of electoral matter with a table listing

the requirements for different actors and different forms of electoral matter

is consistent with recommendations 1 and 2. The objects clauses (recommendation

3) in items 10 and 30 follow the principles presented in

recommendation 1 and are consistent with recommendation 6 that electoral

communication not be unduly interfered with. The consequential amendments to

the broadcasting legislation in the Bill are consistent with recommendation 5.

Recommendation 4 from the Committee’s report was that the

Committee ‘conduct further inquiry and make recommendations in early 2017

regarding the issues of impersonating a Commonwealth officer and Commonwealth

entity’. This recommendation appears to have been pre-empted by the Bill in its

creation of the offence of false representations in relation to a Commonwealth

body in Schedule 2.

Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

On 10 May 2017 the Senate Standing Committee for the

Selection of Bills recommended that the Bill not be referred to a committee for

inquiry and report.[27]

Policy

position of non-government parties/independents

The JSCEM report that led to the Bill was presented as a

unanimous report. The Committee included members from the Coalition, the ALP

and the Greens. Crossbench senators Derryn Hinch and David Leyonhjelm were

participating members for the purpose of the inquiry.

In its submission to the JSCEM inquiry the Liberal

Democrats argued for the removal of any requirement to authorise electoral

material.[28]

There does not appear to have been any media releases or

other media reports suggesting that other Australian federal political parties

are opposed to the authorisation changes suggested in the Committee’s report.

There has not been any substantial media commentary on the Bill since it was

introduced, and the Bill has not yet been debated in Parliament.

Separately to the authorisation provisions, media reports

stated that the Labor Party does not support the amendments in the Bill to

introduce the offence relating to impersonating a Commonwealth body. The Labor

deputy chair of the Committee is quoted as saying:

Malcolm Turnbull is demonstrating contempt for the joint

standing committee on electoral matters ... Changes to criminal law must be

properly considered, as the committee has determined. The integrity of the

electoral system and the healthy functioning of our democracy are more

important than Malcolm Turnbull’s battered ego.[29]

Position of

major interest groups

A number of industry groups provided submissions to the

JSCEM that touched on some of the issues covered in the Bill.

Free TV Australia, a commercial television industry body,

and the Communications Alliance, a communications industry body, provided brief

submissions to the inquiry. Free TV Australia argued against legislation that

increased the regulatory burden on broadcasters who publish political

advertisements and both argued against carriers having any liability or

authorising role under law for political communications that they carried.[30]

The Printing Industries Association of Australia, the peak

industry body for the print, visual communications and media technology sector,

in its submission to the inquiry, argued for the continued requirement that authorisation

be retained for printed material and similar authorisations be required for

non-printed electoral material.[31]

In general, submissions from third party campaigners,

lobbyists and industry organisations focused more on issues such as declaration

of donations than they did on authorisation of electoral matter. There were no submissions

to the JSCEM subsequent to the publication of the Bill that refer specifically

to the provisions of the Bill at the time of publication of this Bills Digest.

At the time of publication there does not appear to have

been any public or media commentary about the specific provisions of the Bill

from interest groups.

Financial

implications

The Explanatory Memorandum for the Bill lists the

financial impact for 2017–18 as being $5.8m, and for 2018–19, 2019–20 and

2010–21 as being $0.9m for each year for proposed Schedule 1 (that is,

the provisions relating to electoral authorisation).[32]

Although not specified in either the Bill or the

Explanatory Memorandum, it is likely that the financial impact of the Bill

relates to the investigatory function of the AEC in relation to authorisation.

The AEC currently has responsibility for regulating

non-compliance with the electoral authorisation provisions of the CEA. The

AEC websites states:

Breaches of sections 328B and 329 [authorisation of

how-to-vote cards and misleading or deceptive publications], because of their

possible impact on the outcome of an election, require immediate action. If

offending material is not immediately withdrawn or amended, the AEC may take

injunction action in accordance with section 383 of the Act. (Note: Injunctive

action may also be taken by a candidate in the election pursuant to section

383.)

If the AEC considers there to be a breach of sections 328 or

328A [publication etc. of electoral advertisements without authorisation],

generally the AEC will write to the relevant person seeking that the material

be withdrawn until such time as the material is amended so as to comply with

the law. In relation to a breach of section 331 [identification of electoral advertisements],

the AEC will write to the relevant person seeking that any future publication

of the same material comply with the law.

If there is continued non-compliance or a more serious breach

of sections 328, 328A, 328B, 329 or 331, the matter may be referred to either,

or both, the Australian Federal Police (AFP) and the Director of Public

Prosecutions (DPP) for further action. Further, because the electoral impact of

a less serious matter may vary according to the circumstances in which it

occurs, the AEC may also consider it appropriate to refer a less serious matter

to either, or both, the AFP and the DPP.

If there is any doubt as to whether there may have been a

breach, the matter will be referred to the DPP for advice.[33]

Under the proposed amendments in the Bill, breaches of the

authorisation requirements will incur a civil, rather than a criminal, penalty

and as such the AFP and the DPP will no longer be involved in the decision to

take action. The increased funding for the first year of operation may be to

allow the AEC to implement training, policies and procedures in order to assume

these investigation and enforcement functions. The recurrent funding may be for

additional staffing to undertake these functions.

The AEC notes that it regards non-compliance during

election periods as potentially more serious due to the potential to affect the

casting of votes, which would therefore result in expected workloads of the

compliance function increasing during election periods. This does not appear to

be reflected in the financial implications.

The Explanatory Memorandum for the Bill notes that the

recovery of civil penalties under the proposed provisions may have an impact on

Government revenue, but that it is unable to be quantified ‘at this time’.[34]

The Explanatory Memorandum does not address the financial

implications of the proposed offence of false representations in relation to a

Commonwealth body. It is likely that this new offence does not have any

specific financial implications. Any financial burden to the Commonwealth in

relation to the new offence will likely affect the DPP and the AFP.

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights (Parliamentary

Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed the Bill’s

compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or declared in the

international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The Government

considers that the Bill is compatible.[35]

Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights

In its 9 May 2017 report, the Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Human Rights advised that it had deferred consideration of

the Bill.[36]

Key issues

and provisions

Authorisation

of electoral material

The Bill would amend the provisions in the electoral

legislation that deal with authorisation of electoral matter and replace them

with more comprehensive and cohesive provisions. Both the CEA and the RMPA

have substantially similar provisions which regulate the authorisation of

electoral matter and the Bill would amend both in substantially similar ways.

As such, these will be discussed together here for simplicity, with differences

noted.

Electoral

matter

Electoral matter is defined in subsections 4(1) and 4(9)

of the CEA. The current definition of ‘electoral matter’ at subsection

4(1) is retained in the Bill. It means ‘matter which is intended or likely to

affect voting in an election’. Item 2 of the Bill adds a reference to

subsection 4(9) in a note to the definition of electoral matter in subsection 4(1).

Without limiting the broad definition of electoral matter in subsection 4(1), subsection

4(9) sets out matters that are taken to be electoral matters. Item 4 would

repeal and replace subsection 4(9) so that matters that are specified as

electoral matters may differ depending on whether or not the term is used in

relation to authorisation of electoral matter.

Under proposed subsection 4(9), material is taken to be

electoral matter in all circumstances if it comments on the election,

political parties or candidates in an election, or issues presented to electors

in connection with an election. Material that refers to these matters is

also taken to be electoral matter, except in proposed Part XXA of the CEA,

which deals with authorisation of electoral matter. That is, material that is

taken to be electoral matter in Part XXA is narrower than that taken to be

electoral matter in all other parts of the CEA.

While the Bill removes explicit reference to the current

or former government or opposition in describing what is taken to be an electoral

matter in subsection 4(9), it adds a note to that subsection that provides that

a comment on a current or previous government in relation to an issue in an

election is an example of an electoral matter. Comment on a ‘a member or former

member of the Parliament of the Commonwealth or a State or of the legislature

of a Territory’ (current paragraph 4(9)(d)) will no longer be specifically taken

to be an electoral matter, although this does not mean that such matters will

not come within the definition of electoral matter, depending on the

circumstances.

Disclosure

entities

Central to the proposed authorisation regimes in both the CEA

and the RMPA is the definition of a ‘disclosure entity’, which is

defined in proposed section 321B in Part XXA of the CEA (or

proposed section 110A in the case of the RMPA amendments).[37]

The authorisation requirements for electoral matter will vary depending on

whether or not the individual or entity publishing the electoral matter is a

disclosure entity.

The concept of a disclosure entity is explicitly connected

to the requirements to disclose under Part XX, the election funding and

financial disclosure provisions of the CEA (this is also true of the proposed

amendments in the Bill to the RMPA, which reference the CEA).

Current and former candidates (for the previous four years for candidates for

election to the House of Representatives or seven years for candidates for

election to the Senate), registered political parties and current senators and

Members of the House of Representatives are disclosure entities.

Associated entities, which are defined under Part XX of

the CEA, are disclosure entities. Associated entities include unions

that pay affiliation fees to political parties and organisations that are set

up as fundraising vehicles by political parties.

In addition, individuals or organisations who are required

to submit returns to the AEC because they have donated to a party or a

candidate, or have incurred reportable political expenditure, above the disclosure

threshold (currently $13,200)[38]

are disclosure entities.

The required particulars for authorisation for disclosure

entities is designed to allow the electoral matter to be easily linked to the

entity’s other involvement in the election, such as their donations, status as

an associated entity, or political expenditure, which is made public through

the AEC’s electoral returns database.

Authorisation

The CEA currently addresses the authorisation of

electoral material in three sections, all of which are in Part XXI of the Act,

covering electoral offences:

- section

328, which covers physical electoral material, other than how-to-vote (HTV)

cards, including flyers, posters, and newspaper advertisements (with a small

number of specific exemptions, such as t-shirts, badges and business cards)

- section

328A, which specifically regulates electoral advertising on the Internet and

- section

328B, which regulates authorisation of HTV cards.

The internet-specific provisions in section 328A were

inserted by the Electoral and Referendum Amendment (Electoral Integrity and

Other Measures) Act 2006[39]

in response to a recommendation by the JSCEM’s inquiry into the 2004 federal

election. The Committee viewed the application of section 328 to electoral

material on the internet as ‘cumbersome, and perhaps unenforceable’, and

recommended that specific provisions be made for internet electoral matter that

made clear it was distinct from general commentary on the internet

(recommendation 44).[40]

In the decade since the addition of section 328A the

distinction between offline and online electoral matter has become increasingly

superfluous. Electoral video recordings, which are today most likely to be

distributed on the internet, are regulated under section 328, for example.

Identical flyers might be distributed to interested parties in physical form,

in electronic form with the intention that they be printed out, or with the

intention they be viewed electronically. And, for certain communications such

as text messages and automated voice calls, it is not clear whether

authorisation is required.

The Bill proposes repealing these sections (item 11

of Schedule 1). It would also repeal section 331, which requires electoral

advertisements in newspapers to carry the heading ‘Advertisement’ and section

334 which bans the depiction of electoral material ‘directly on any roadway,

footpath, building, vehicle, vessel, hoarding or place (whether it is or is not

a public place and whether on land or water or in the air)’ (item 12).

The RMPA has two sections that regulate

authorisation in printed and published forms (section 121) and on the internet

(section 121A). Section 124 requires electoral advertising in newspapers to

carry the heading ‘Advertisement’. These three sections would be repealed by

the Bill (item 31).

Item 10 of Schedule 1 to the Bill would insert proposed

Part XXA, which collects together the provisions regulating authorisation,

into the CEA. Similarly, item 30 would amend the RMPA to

insert proposed Part IX, regulating the authorisation of referendum

material.

The key provision relating to authorisation of electoral

matter is in proposed section 321D, which:

- provides

for which electoral matter requires authorisation and which does not

- includes

a table specifying what authorisation is required for different forms of

electoral matter and

- allows

the Electoral Commissioner to issue a disallowable legislative instrument

specifying certain aspects of authorisation requirements.

Proposed subsections 321D(1) and (2) provide

that the authorisation requirements apply to a broad range of electoral matter communications.

In the notes to the subsection internet advertisements, bulk text messages and

bulk voice calls containing electoral matter are communications that are explicitly

mentioned as being covered by the provisions.

Any electoral matter communicated by a disclosure entity, specific

printed matter (including stickers, fridge magnets, posters and HTV cards) that

is approved by a person, and other electoral advertising that is authorised by

a person and paid for, are included under subsection 321D(1). Subsection 321D(2)

specifies who is responsible for making the authorisation if the electoral

matter is being communicated by one entity on behalf of another. The individual

responsible for making the disclosure will be the ‘notifying entity’.

Proposed subsections 321D(3) and (4) provide

exceptions to the authorisation requirements. Briefly, clothing or anything

that is designed to be worn is specifically exempted, as are reporting of the

news, communication for satire, academic or artistic purposes, internal or

personal communications, and meetings or live broadcasts of meetings where the

speaker can be reasonably identified. Recorded broadcasts of meetings will

require authorisation.

Proposed subsection 321D(5) contains a table that

lists the specific authorisation requirements, or ‘required particulars’ for different

forms of electoral matter. It has separate requirements for:

- specific

printed electoral matter (stickers, fridge magnets, leaflets, flyers,

pamphlets, notices, posters or HTV cards, collectively referred to in the

Explanatory Memorandum as ‘specified printed matter’) and ‘any other

communication’

- those

who are and are not disclosure entities and

- those

who are and are not natural persons.

For example, if a union that is an associated entity (and

hence a disclosure entity) posts a picture on Facebook that is about an

election and intended to influence voting in an election, it would be covered

under item 2 of the table in proposed subsection 321D(5) and would

require that it listed the name of the union, the relevant town or city where

it had its principal office (as defined by proposed section 321B), and

the name of a person responsible for authorising the matter.

Failure to correctly authorise the matter would result in

a civil penalty of a maximum 120 penalty units (currently $21,600). Paragraph 82(5)(a)

of the Regulatory Powers (Standard Provisions) Act 2014 (Regulatory

Powers Act)[41]

states that if the person is a body corporate the maximum pecuniary penalty is

five times the specified penalty (600 penalty units, or $108,000).

Item 30, which proposes to amend the RMPA,

is essentially the same as item 10, with the addition of an exemption

from authorisation if material is communicated by or on behalf of a state or

territory or an authority of a state or territory (proposed paragraph

110C(3)(b)).

How-to-vote

cards

Under the CEA, HTV cards and other printed

electoral matter are treated separately, and arguably inconsistently. Section

328B of the CEA specifically regulates the authorisation requirements

for HTV cards for federal electoral events, whereas the proposed Bill incorporates

HTV cards in with the regulation of authorisation of the specified printed

material.

Under the Bill HTV cards will no longer have to be

authorised on each printed page and will no longer be required to include the

word ‘candidate’ for candidates who authorise their own HTV cards (unless the determination

issued by the Electoral Commissioner under proposed subsection 321D(7) subsequently

require this). Under the Bill, HTV cards would need to include the name and

address of the printer who printed the HTV card.

It is not clear how the authorisation requirements under

the proposed Bill will deal with ‘second preference HTV cards’, where a party

or candidate issues a HTV card designed to be mistaken for another party’s

official HTV card, but with the issuing candidate or party listed as the second

preference. The AEC states that second preference HTV cards would probably be

held by courts to be in contravention of subsection 329(1) of the CEA

(which relates to misleading advertising), which is not affected by the Bill,

however, also notes that the requirements of section 328B that the relevant

candidate or party’s name be on both side of the HTV card, which will be

removed by the Bill, also serves to prevent second preference HTV cards.[42]

Proposed subsection 321D(5) would retain the requirement for the

issuing party’s name to be included on the HTV card, and the Electoral

Commissioner’s determination under proposed subsection 321D(7) may

require the party name to be included on each printed face, as under subsection

328B(1).

Electoral

Commissioner’s determination

Much of the specific detail of how the authorisation

requirements will work in practice is missing from the Bill as it will form

part of the legislative instrument issued by the Electoral Commissioner under

proposed subsection 321D(7). For example, the Explanatory Memorandum notes that

the Bill does not impose specific requirements for when in relation to a

broadcast political advertisement the authorisation must air, but notes that

this will be defined in the proposed subsection 321D(7) determination.[43]

It further notes that the Electoral Commissioner will be required to consult

with relevant stakeholders, including broadcasters, in making this

determination.[44]

As noted above, the current requirement for HTV cards to

carry authorisations on each printed side is absent from the Bill, but may be

added under the determination.

Whilst this approach allows for more flexibility in a

changing media environment, and allows for the legislative instrument to add

new media or communications forms as they arise, it also impacts on the ability

of the Bill to simplify the authorisation requirements. The simplified table in

proposed subsection 321D(5) alone may not provide sufficient information

to correctly authorise a piece of communication—those undertaking public

political communication must consult both the CEA and the legislative

instrument, however complex it may be.

Investigations

and injunctions in relation to authorisations

The sections of the CEA relating to electoral

authorisations being repealed and replaced by the Bill make the failure to

correctly authorise electoral material a criminal offence. As discussed above,

breaches of these offences are referred to the AFP and the DPP to investigate

and prosecute, and it is the responsibility of the AFP and DPP to determine

whether there is sufficient evidence of an offence to warrant investigation and

prosecution.

By imposing a civil penalty under the Regulatory Powers

Act,[45]

breaches of proposed section 321D will be investigated and enforced by

the AEC. Item 27 of Schedule 1 inserts proposed section 384A into

the CEA, to provide that breaches of proposed section 321D are

enforceable under the Regulatory Powers Act as a civil penalty or an enforceable

undertaking (item 45 in the case of the RMPA). Division 3 of the

proposed Part XXA of the CEA, and Division 3 of the proposed Part IX of

the RMPA, supply the AEC with investigatory powers in order to undertake

these investigations and enforcement in relation to electoral authorisation.

Proposed section 321F gives the Electoral

Commissioner the power to obtain information or documents from persons,

requiring the Electoral Commissioner to have regard to the costs of supplying

those documents, and allowing compensation to be paid for complying with the

request. Proposed section 321G allows the Electoral Commissioner to copy

documents obtained under proposed section 321F and retain those copies,

and proposed section 321H allows the documents themselves to be retained

as long as necessary. These powers operate explicitly to allow the Electoral

Commissioner to assess compliance with electoral authorisation requirements.

The existing provisions on injunctions in section 383 of

the CEA are expanded in items 14 through 26 to specifically allow

injunctions to be granted against carriage service providers. These injunctions

target carriage service providers such as phone companies that distribute bulk

voice calls or bulk text messages if the communication that they are carrying

is, or may be, in breach of proposed section 321D. As with existing

section 383 injunctions, an application for the injunction can be brought by

either a candidate in the election or the Electoral Commissioner. Substantially

similar amendments are proposed to the RPMA section 139 relating to

injunctions in items 32 through 44.

The proposed authorisation provisions are the only

provisions in the CEA to which a civil penalty would apply. The

Government has not stated why these specific provisions are considered to be

appropriate for a civil enforcement regime, whilst the rest of the contraventions

under the Act retain criminal penalties. The JSCEM report did not make specific

recommendations as to whether the penalties should be criminal or civil.

Potential

issues with enforcement

With such comprehensive coverage of electoral matter to be

authorised it is not clear how practical all of the proposed provisions will be,

particularly in the absence of the proposed subsection 321B(7) determination.

For example, a person who donates an amount to a political party above the

disclosure threshold (currently $13,200)[46]

would be required to submit a return under section 305B, and is thus considered

to be a disclosure entity. A person who has not donated to a political party,

in contrast, would not be subject to proposed section 321D authorisation

requirements unless the electoral matter is either specified printed matter or

has been paid for.

If an individual who is a disclosure entity places a post

on Twitter advocating that people vote for a certain party, this would appear

to require notification under proposed paragraph 321D(1)(c), assuming

that this would not be considered a ‘communication communicated for personal

purposes’ and therefore exempt under proposed paragraph 321D(4)(d). The

communication would require particulars under item 4 of the table in proposed

subsection 321D(5) consisting of the person’s name and the town or city in

which they live.

Exactly how that required information is attached to the

communication is not specified in the Bill, and would be presumably dependent

on the legislative instrument issued by the Electoral Commissioner under proposed

subsection 321D(7). In the absence of such a legislative instrument, it is

not clear whether the required particulars would need to be included in the

text of the tweet (using some of the 140 characters available), or whether it

is sufficient for the information to be included in the individual’s Twitter

biography section, which may or may not be easily accessible from the text of

the post. Note that the Regulatory Powers Act does not require intent to

be proved in order for a contravention of a civil penalty provision to be

established (section 94), but does have a defence of a mistake of fact (section

95), so enforcement might be difficult in the absence of an advertising

campaign to notify the public of the change.

Bulk text messages are also explicitly covered under the

Bill. The Medicare related text messages sent by the Queensland ALP during the

2016 federal election campaign would be covered under item 2 of the

table in proposed subsection 321D(5) and therefore must include the name

of the entity, the relevant town or city, and the name of the person giving the

authorisation. Text messages were originally limited to 160 characters, and

longer text messages are sent as a number of short text messages that are

reassembled before viewing. Therefore a text message that is long enough to contain

the required particulars will typically in reality consist of a number of text

messages, some of which will not contain the required particulars. One or more

of these component messages may be reordered or lost in transit which may

result in the overall message not being correctly authorised.

One area that might prove difficult to regulate under the

Bill relates to ‘astroturfing’, or campaigns that are organised to appear as

spontaneous or unsolicited comments from the community. For example, if a candidate

or party engages individuals (even in the absence of payment) to promote the

candidate or party on social media, those social media posts must, under proposed

subsection 321D(5), include the required particulars (for a party being the

name of the party, the relevant town or city, and the name of the person who

authorised the communication). It is not clear how effective the information

gathering powers that Division 3 of proposed Part XXA gives to the AEC

would be in uncovering the identity of the posters, particularly where

Australians are posting on a social media site hosted overseas.

Similarly, if during an election campaign any campaign

workers were instructed to call into a talk-back radio station in the guise of

a listener to promote the party’s daily talking points, disclosure would be

required under the Bill. If the campaign worker was to either use their own

name and not disclose the required particulars, or was to use a false name, the

party would be in breach of proposed section 321D. If an individual

suspected that this behaviour was in breach and reported their suspicions to

the AEC, it is not clear what discretion the AEC has to investigate the alleged

breach or to determine that it is insufficiently serious to merit the required investigatory

resources during the election period. However, should the AEC determine that a

breach had occurred, under the Regulatory Powers Act (Part 6) it could accept

an enforceable undertaking to prevent further breaches or apply for an

injunction under the CEA.

Particularly in a close election, electoral actors have

been known to push the boundaries of what is and is not legal as far as

electoral advertising goes (the Medicare text messages are arguably an example

of this). They may do this in the knowledge that even if their communication is

found to not be legal and in breach of the Act, regulation and enforcement

might be slow, and the message might have had its intended effect before it is

halted.

Continuing the example of the Medicare text messages, even

under the proposed provisions of the Bill that allow injunctions against

carriage service providers, the period between when the message is broadcast

and when the injunction is imposed may be enough to influence sufficient

numbers of voters to make a difference.

Electoral advertising is counted in the millions of

dollars (at the 2016 federal election the Liberal Party spent $6 million

and the Labor party $4.7 million),[47]

and therefore a civil penalty of up to $108,000 may not be seen as a

significant deterrent to some parties if it increases their chance of winning

the election. In the absence of a criminal trial and potential conviction, it

could be priced into the election advertising budget. As such, the practical

deterrent effect of the measures proposed in the Bill remains to be seen.

Impersonating

a Commonwealth body

Schedule 2 of the Bill contains a proposed

amendment to the Criminal Code Act 1995[48]

to create a new Division to the Act and to create a new offence of ‘false

representations in relation to a Commonwealth body’. The proposed offence is

added to the existing offences in Part 7.8 of the Criminal Code Act

relating to ‘causing harm to, and impersonation and obstruction of, Commonwealth

public officials’. The existing offences cover:

- causing

harm to Commonwealth public officials

- threatening

to cause harm to a Commonwealth public official

- impersonating

an official and

- obstruction

of Commonwealth public officials.

The proposed offence is, in intent, although not

structure, most similar to section 148.1, ‘impersonation of an official by a

non-official’. In the second reading speech it was noted that it was not clear

whether these existing provisions covered the situations addressed by the

proposed new offence, hence the need for the new offence.[49]

Similarly to section 148.1, the offence distinguishes

between conduct carried out with the intent to obtain a gain, cause a loss, or

influence the exercise of a public duty or function, which carries a maximum penalty

of five years imprisonment, and that which does not have that intent, which

carries a maximum penalty of two years imprisonment.

The proposed amendment specifies that the government

department need not exist in order for the offence to apply, however, if the

body does not exist the offence does not apply unless a person would reasonably

believe that the department does exist. In addition, the offence does not apply

for conduct that is for satirical, artistic or academic purposes.

Due to its inclusion in a Bill that otherwise addresses

electoral issues, the new offence appears to target behaviour such as that seen

with the pre-election ‘Medicare’ text messages. As noted above, in the Prime

Minister’s election night speech he stated, ‘And the message, the message, the

SMS message came from Medicare. It said it came from Medicare. An extraordinary

act of dishonesty. No doubt the police will investigate’.[50]

The proposed amendment states that the offence does not

apply if it would infringe the implied freedom of political communication in

the Australian Constitution. The law being applied against a major

political party in the midst of an election campaign would be a substantial

test of that. Following McCloy v New South Wales[51]

the application of the law against a political advertisement would have to pass

the proportionality test. That is, if the law burdens the freedom of political

communication, is it suitable, necessary, and adequate in its balance?:

A law is ‘suitable’ if it has a rational connection to its

purported purpose. It is ‘necessary’ if there is ‘no obvious and compelling

alternative, reasonably practicable means of achieving the same purpose which

has a less restrictive effect on the freedom’. It is ‘adequate in its balance’

if the court makes the value judgment that the importance of the purpose served

by the law outweighs the extent of the restriction that it imposes on the

freedom.[52]

If the proposed offence was applied to the text messages

which were apparently from Medicare it would likely require an appeal to the

High Court to determine whether the message was constitutionally protected.

The proposed offence would not appear to apply to the fake

Medicare cards being handed out to voters by the unions as it seems likely that

these would be viewed as not ‘reasonably capable of resulting’ in a

representation on behalf of a Commonwealth body, due to the card being

obviously not a genuine Medicare card.[53]

Other provisions

The provisions in Part 2 of Schedule 1 of the Bill

consequentially amend four pieces of broadcasting legislation (Australian

Broadcasting Corporation Act 1983, Broadcasting Services Act 1992, Parliamentary

Proceedings Broadcasting Act 1946 and Special Broadcasting Service Act

1991) to make them consistent with the changes in the CEA.

The proposed amendments to the Parliamentary

Proceedings Broadcasting Act 1946 in item 62 only update it to insert

references to the CEA and RMPA. The remaining three broadcasting

acts already include requirements for broadcasters to include authorisations

for electoral material and the proposed amendments replace these requirements

with references to the proposed sections in the CEA, including the relevant

sections of the table in proposed subsection 321D(5).[54]

As part of replacing the required particulars, the

proposed amendments to the broadcasting legislation remove the requirement for

electoral advertising to identify who is speaking in an electoral advertisement

(items 51, 55 and 67).

In each case the proposed

amendments require the broadcaster to take reasonable steps to verify the

accuracy of the supplied required particulars for electoral advertising (items

52, 60 and 68). The Bill provides examples of these steps, including

notifying those who wish to broadcast political matter of the requirements, and

seeking a verification as to whether the person is a disclosure entity (to

determine which of the specific required particulars applies).

The exact form in which the authorisation will be

broadcast in association with the political matter will be determined by the

legislative instrument issued by the Electoral Commissioner under proposed

subsection 321D(7).

Concluding

comments

Although nominally a regulatory agency, the AEC has

generally managed to remain outside the political fray by taking a fairly

light-touch approach to regulating political communication and deferring much

of the decision making relating to investigating and prosecuting electoral

offences to other agencies, such as the AFP and the DPP. By empowering the AEC

to apply for injunctions, and investigate and prosecute certain classes of

electoral offences, the proposed Bill involves the AEC much more directly in regulating

political communication, and in the potential political fallout that its

decisions might generate doing so in the midst of an election.

While the exact implications of this remain to be seen, it is worth noting that

the Bill substantially changes the regulatory relationship between the AEC and

political actors, including potentially the parties of Government and opposition.

[1]. Commonwealth

Electoral Act 1918.

[2]. Referendum

(Machinery Provisions) Act 1984.

[3]. Criminal Code Act 1995.

[4]. Australian

Broadcasting Corporation Act 1983.

[5]. Broadcasting

Services Act 1992.

[6]. Parliamentary

Proceedings Broadcasting Act 1946.

[7]. Special

Broadcasting Service Act 1991.

[8]. P

Dutton (Minister for Health), EOI

for Medicare-PBS payment services, media release,

8 August 2014.

[9]. Ibid.

[10]. S

Duckett, ‘Is

Medicare under threat? making sense of the privatisation debate’, The

Conversation, 23 June 2016.

[11]. P

Bongiorno, ‘Faust

among equals’, The Saturday Paper, 25 June 2016, p. 15.

[12]. P

Correy, ‘“Mediscare”

delivers poll boost for Labor’, Australian Financial Review, 24 June

2016, p. 1.

[13]. R

Viellaris and J Tin, ‘Shorten

retreats on scare tactics’, Courier Mail, 29 June 2016, p. 13; P

Williams, ‘Malcolm

threw in millions but cash can’t silence the critics’, The Australian,

18 July 2016, p. 1.

[14]. Joint

Standing Committee on Electoral Matters (JSCEM), Official

committee Hansard, 11 November 2016.

[15]. J

Taylor, ‘ALP

says it was just following the rules on “Mediscare” SMS’, Crikey, 4

November 2016.

[16]. E

Moorhead (State Secretary, Australian Labor Party Queensland Branch), Evidence

to Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters, Inquiry into the conduct of

the 2016 federal election and matters related thereto, 31 January 2017.

[17]. M

Turnbull, ‘Steady

hand more crucial than ever’, Australian Financial Review, 27 June

2016, p. 4.

[18]. M

Turnbull, ‘Malcolm

Turnbull, Bill Shorten election night speeches in full’, Herald Sun,

(online edition), 3 July 2016.

[19]. Ibid.

[20]. K

Middleton, ‘The

new untruth of political campaigns’, The Saturday Paper, 17 December

2016, p. 1.

[21]. JSCEM,

The

2016 federal election: interim report on the authorisation of voter

communication, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, December 2016.

[22]. JWS

Research, Post

election survey: July 2016, JWS Research, Melbourne, July 2016.

[23]. S

Ryan (Special Minister of State, Minister Assisting the Cabinet Secretary and

Senator for Victoria), JSCEM

asked to report on 2016 election, media release, 14 September 2016.

[24]. JSCEM,

The

2016 federal election: interim report on the authorisation of voter

communication, op. cit.

[25]. J

Frydenberg, ‘Second

reading speech: Electoral and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2017’, House

of Representatives, Debates, 30 March 2017, p. 3792.

[26]. JCSEM,

‘Inquiry

into and report on all aspects of the conduct of the 2016 federal election and

matters related thereto’, Parliament of Australia website, 2017.

[27]. Australia,

Senate, Journals,

41, 2016–17, 11 May 2017, p. 1346.

[28]. Liberal

Democratic Party, Submission

to Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters, Inquiry into and report on

all aspects of the conduct of the 2016 Federal Election and matters related

thereto, 31 October 2016.

[29]. K

Murphy, ‘Don’t

rush the electoral reform changes, Labor warns government’, The Guardian,

(online edition), 16 February 2017.

[30]. Communications

Alliance and Australian Mobile Telecommunications Association, Submission

to Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters, Inquiry into and report on

all aspects of the conduct of the 2016 Federal Election and matters related

thereto, 1 November 2016; Free TV Australia, Submission

to Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters, Inquiry into and report on

all aspects of the conduct of the 2016 Federal Election and matters related

thereto, 1 November 2016.

[31]. Printing

Industries Association of Australia, Submission

to Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters, Inquiry into and report on

all aspects of the conduct of the 2016 Federal Election and matters related

thereto, November 2016.

[32]. Explanatory

Memorandum, Electoral and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2017, p. 4; The

Explanatory Memorandum does not list the units for the financial impact,

however, the Department of Finance has confirmed that the figures are in

millions of dollars.

[33]. Australian

Electoral Commission (AEC), ‘Electoral

backgrounder: electoral advertising’, AEC website, 9 June 2016.

[34]. Explanatory

Memorandum, Electoral and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2017, p. 4.

[35]. The

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights can be found at page 5 of the

Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill.

[36]. Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights, Report, 4, 2017, The Senate, Canberra, 9

May 2017, p. 155.

[37]. See

items 10 and 30 of Schedule 1 to the Bill.

[38]. AEC,

‘Disclosure

threshold’, AEC website, 19 May 2016.

[39]. Electoral and

Referendum Amendment (Electoral Integrity and Other Measures) Act 2006.

[40]. JSCEM,

The 2004 federal election: report

of the Inquiry into the conduct of the 2004 federal election and matters

related thereto, Canberra, September 2005, pp. 278–279.

[41]. Regulatory Powers

(Standard Provisions) Act 2014. Proposed section 384A of the CEA,

inserted by item 27 of Schedule 1 to the Bill, provides that section

321D is enforceable under Part 4 (civil penalty provisions) and Part 6

(enforceable undertakings) of the Regulatory Powers (Standard Provisions)

Act. For information on the Regulatory Powers (Standard Provisions) Act see:

C Raymond, Regulatory

Powers (Standardisation Reform) Bill 2016, Bills digest, 42, 2016–17,

Parliamentary Library, Canberra, 2016.

[42]. AEC,

‘Electoral

backgrounder: electoral advertising’, AEC website, 9 June 2016.

[43]. Explanatory

Memorandum, Electoral and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2017, p. 44.

[44]. Section

17 of the Legislation

Act 2003 provides that a rule-maker should undertake appropriate

consultation before making a legislative instrument. A failure to consult,

however, does not affect the validity or enforceability of a legislative

instrument (section 19).

[45]. Regulatory Powers

(Standard Provisions) Act 2014.

[46]. AEC,

‘Disclosure

threshold’, AEC website, 19 May 2016.

[47]. A

Hickman, ‘Election

2016: Liberal in box seat after positive ad campaign’, AdNews, 1

July 2016.

[48]. Criminal Code Act

1995.

[49]. J

Frydenberg, ‘Second

reading speech: Electoral and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2017’, House

of Representatives, Debates, 30 March 2017, p. 3792.

[50]. M

Turnbull, ‘Malcolm

Turnbull, Bill Shorten election night speeches in full’, op. cit.

[51]. McCloy

v New South Wales (2015) 257 CLR 178, [2015] HCA 34.

[52]. A

Twomey, ‘Proportionality

and the Constitution’, Australian Law Reform Commission website, 8 October

2015.

[53]. The

card was thin cardboard, had text such as ‘Save bulk billing’, and carried an

electoral authorisation for the ACTU on the rear.

[54]. Excluding

the required particulars for certain printed matter.

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.

In essence, you are free to copy and communicate this work in its current form for all non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute the work to the author and abide by the other licence terms. The work cannot be adapted or modified in any way. Content from this publication should be attributed in the following way: Author(s), Title of publication, Series Name and No, Publisher, Date.

To the extent that copyright subsists in third party quotes it remains with the original owner and permission may be required to reuse the material.

Inquiries regarding the licence and any use of the publication are welcome to webmanager@aph.gov.au.

Disclaimer: Bills Digests are prepared to support the work of the Australian Parliament. They are produced under time and resource constraints and aim to be available in time for debate in the Chambers. The views expressed in Bills Digests do not reflect an official position of the Australian Parliamentary Library, nor do they constitute professional legal opinion. Bills Digests reflect the relevant legislation as introduced and do not canvass subsequent amendments or developments. Other sources should be consulted to determine the official status of the Bill.

Any concerns or complaints should be directed to the Parliamentary Librarian. Parliamentary Library staff are available to discuss the contents of publications with Senators and Members and their staff. To access this service, clients may contact the author or the Library‘s Central Enquiry Point for referral.