Tax and Superannuation Laws Amendment (2013 Measures No. 1) Bill 2013

Bills Digest no. 97 2012–13

PDF version [956KB]

WARNING: This Digest was prepared for debate. It reflects the legislation as introduced and does not canvass subsequent amendments. This Digest does not have any official legal status. Other sources should be consulted to determine the subsequent official status of the Bill.

Kai Swoboda and Paige Darby

Economics Section

27 March 2013

Contents

Glossary

Purpose of the Bill

Structure of the Bill

Committee consideration

Schedule 1–Interest on unclaimed money

Schedule 2—Airline transport fringe benefits

Schedule 3—Rural water use

Schedule 4—Acquisitions and disposals of certain assets between related parties for self managed superannuation funds

Schedules 5 and 6—Loss carry-back

Schedule 7—Miscellaneous amendments

This Bills Digest uses the following abbreviations:

|

Abbreviation |

Definition |

|

ATSIC |

Australian Securities and Investments Commission

|

|

ATO

|

Australian Taxation Office

|

|

BTWG

|

Business Tax Working Group

|

|

CGT

|

Capital Gains Tax

|

|

COT

|

Continuity of Ownership Test

|

|

DASP

|

Departing Australia Superannuation Payment

|

|

FBT

|

Fringe Benefits Tax

|

|

FBTAA

|

Fringe Benefits Tax Assessment Act 1986

|

|

IT(TP)A 1997

|

Income Tax (Transitional Provisions) Act 1997

|

|

ITAA 1936

|

Income Tax Assessment Act 1936

|

|

ITAA 1997

|

Income Tax Assessment Act 1997

|

|

MRRT

|

Minerals Resource Rent Tax

|

|

MRRT(CATP)A 2012

|

Minerals Resource Rent Tax (Consequential Amendments and Transitional Provisions) Act 2012

|

|

MRRTA 2012

|

Minerals Resource Rent Tax Act 2012

|

|

MYEFO

|

Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook

|

|

NANE

|

Non-assessable non-exempt

|

|

PAYG

|

Pay-as-you-go

|

|

PRRT

|

Petroleum Resource Rent Tax

|

|

PRRTAA 1987

|

Petroleum Resource Rent Tax Assessment Act 1987

|

|

RIS

|

Regulation Impact Statement

|

|

S(DASPT) Act

|

Superannuation (Departing Australia Superannuation Payment Tax) Act 2007

|

|

S(UMLM) Act

|

Superannuation (Unclaimed Money and Lost Members) Act 1999

|

|

SBT

|

Same Business Test

|

|

SIS Act

|

Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993

|

|

SIS Regulations

|

Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Regulations 1994

|

|

SMSF

|

Self managed superannuation fund

|

|

SRWUIP

|

Sustainable Rural Water Use and Infrastructure Program

|

|

SUMLA Act

|

Superannuation (Unclaimed Money and Lost Members) Act 1999

|

|

TAA 1953

|

Taxation Administration Act 1953

|

|

TIOEPA 1983

|

Taxation (Interest on Overpayments and Early Payments) Act 1983

|

|

Water Department

|

Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities

|

|

Water Minister

|

Minister for Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities

|

Date introduced: 13 February 2013

House: House of Representatives

Portfolio: Treasury

Commencement: The commencement and application of the measures in each Schedule is indicated in the key provisions section of this Bills Digest

Links: The links to the Bill, its Explanatory Memorandum and second reading speech can be found on the Bill's home page, or through http://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Bills_Legislation. When Bills have been passed and have received Royal Assent, they become Acts, which can be found at the ComLaw website at http://www.comlaw.gov.au/.

The purpose of the Tax and Superannuation Laws Amendment (2013 Measures No. 1) Bill 2013 (the Bill) is to amend taxation and superannuation laws for various purposes. Specifically, the Bill:

- amends the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (ITAA 1997)[1], the Superannuation (Departing Australia Superannuation Payments Tax) Act 2007 (S(DASPT) Act)[2] and the Superannuation (Unclaimed Money and Lost Members) Act 1999 (S(UMLM) Act)[3] to ensure that income tax is generally not payable on interest paid by the Commonwealth on unclaimed money from 1 July 2013

- amends the Fringe Benefits Tax Assessment Act 1986 (FBTAA)[4] to align the rule for calculating airline transport fringe benefits with existing in-house property fringe benefits[5] and in-house residual fringe benefits[6]. Correspondingly, there is an update to the method for determining the taxable value of airline transport fringe benefits

- amends the ITAA 1997 to allow participants in the Sustainable Rural Water Use and Infrastructure Program (SRWUIP) to choose to make payments received under the program non‑assessable non-exempt (NANE) income[7], in which case expenditure related to infrastructure improvements required by the program are then non-deductible as they do not form part of the cost of any asset

- amends the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 (SIS Act)[8] to prescribe requirements for acquisitions and disposals of certain assets between self managed superannuation funds (SMSFs) and related parties in order to increase transparency and compliance

- amends the ITAA 1997 to introduce the loss carry-back tax offset, which allows a corporate tax entity to carry back all or part of a tax loss (of up to $1 million) from the current year against income tax payable for either of the two preceding income years

- amends the ITAA 1997 to make consequential amendments made necessary by the introduction of the loss carry-back tax offset and

- makes miscellaneous amendments to address minor technical deficiencies and legislative uncertainties within taxation laws, particularly the Minerals Resource Rent Tax Act 2012 (MRRTA 2012)[9] and the Petroleum Resource Rent Tax Assessment Act 1987 (PRRTAA 1987).[10]

The Bill is separated into seven Schedules, which will be dealt with individually within this Bills Digest.

The Bill was referred to the Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services for inquiry and report by 18 March 2013. Details of the inquiry are at: http://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate_Committees?url=corporations_ctte/completed_inquiries/2010-13/taxandsuper/index.htm.[11]

The Committee’s majority report, tabled in the Senate on 19 March 2013, recommended that the Bill be passed.[12] However, a dissenting report by Coalition members of the Committee recommended that the Bill not be passed unless Schedule 4, which deals with transfer of assets with SMSFs, and Schedules 5 and 6, which deal with the loss carry-back changes (measures linked to the MRRT), are excised from the Bill.[13]

The Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills made no comment on the Bill.[14] The Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights has sought clarification from the Treasurer about whether the penalties imposed by Schedules 4 and 7 may be characterised as criminal for the purposes of articles 14 and 15 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.[15]

In October 2013, as part of the 2012–13 Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook, the Government announced changes to unclaimed money and lost superannuation arrangements that effectively brought forward the time period, or reduced the threshold on the value of funds, for the transfer of funds to consolidated revenue. As part of the revised arrangements, interest would be payable on these transferred amounts for the first time.[16]

The legislation implementing these proposed changes—the Treasury Legislation Amendment (Unclaimed Money and Other Measures) Bill 2012—was passed by the Parliament on 29 November 2012 and given Royal Assent on 4 December 2012.[17] The commencement date for the payment of interest is 1 July 2013.

During parliamentary consideration of that Bill, the Treasury submission to the Senate Economics Committee noted that interest paid on transferred balances for unclaimed money would be exempt from tax.[18] Legislation to implement the tax exemption was to be introduced in early 2013.[19]

This Bill implements the tax exemption for interest on these payments.

In some circumstances money is held by a financial institution (such as a bank, life insurance provider or superannuation fund) on behalf of an owner where the institution has lost contact with and cannot locate the owner. After a specified period of time or at a certain value of account, these funds become unclaimed money and are then transferred on an annual or biannual basis to the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) or the Australian Securities Investments Commission (ASIC), whereupon it becomes part of consolidated revenue.

There are a number of different types of lost and unclaimed money under various legislation and there are separate rules relating to each type requiring transfer to either the ATO or ASIC. The accumulated balances of lost and unclaimed moneys are significant. Registers maintained by ASIC and the ATO, which in relation to life insurance extend as far back as 1952, report a total of more than $18 billion in funds that may potentially be repaid to claimants, with interest from 1 July 2013, at some time in the future (Table 1).

Table 1 Value of accumulated lost and unclaimed money ($ million)

|

Type of lost and unclaimed money

|

Total value ($ million) (a)

|

|

Superannuation

|

|

|

Lost uncontactable

|

9000

|

|

Lost inactive

|

7800

|

|

Unclaimed

|

887

|

|

Bank accounts

|

314

|

|

Life insurance

|

50

|

|

|

338

|

|

Total

|

18 389

|

Note: (a) Superannuation amounts as at 30 June 2012. Other amounts as at 14 February 2013.

Sources: Australian Taxation Office (ATO), Annual report 2011–12, Commonwealth of Australia, 2012, p. 87, viewed 24 November 2012, http://annualreport.ato.gov.au/uploadedFiles/Content/Downloads/n0995-10-2012_js23899_w.pdf; ASIC registers as published by ASIC at: http://www.asic.gov.au/asic/asic.nsf/byheadline/Unclaimed+money+lists?openDocument

Under current arrangements, certain temporary residents departing Australia are able to withdraw their superannuation balances when they leave or have left Australia.[20] When withdrawn, the payment (defined as a ‘departing Australia superannuation payment’ (DASP)) is taxed at various rates depending on the components of the superannuation benefit.[21]

In the case of interest paid on the unclaimed money of former temporary residents, the Bill provides that the interest payment will be subject to a 45 per cent tax rate.

At the time of publication of this Bills Digest, the Coalition, the Australian Greens and independents had not expressed a view on providing for the interest paid on lost and unclaimed moneys to be tax‑free. However, their positions on the Treasury Legislation Amendment (Unclaimed Money and Other Measures) Bill 2012, which provided for interest payments on these amounts at the rate of CPI, may be a guide to the position they may take on this Bill.

The Coalition opposed the Treasury Legislation Amendment (Unclaimed Money and Other Measures) Bill 2012, voting against the Bill in the House of Representatives and the Senate.[22] The Coalition’s initial opposition was largely based on the short timeframe given for debate on the Bill rather than the merits of the proposed changes.[23] A dissenting report by Coalition Senators for the Senate Economics Committee inquiry into the Bill included a number of additional points of opposition, including a proposal for further consultation on the inactivity threshold and for the threshold to be applied only to low-interest accounts, but did not directly address the payment of interest on transferred balances nor the proposed tax exemption on these amounts.[24]

Although several Coalition parliamentary members contributing to the debate on the Bill canvassed the issue of the interest rate being paid at the rate of the consumer price index being less than that applied to some accounts, none directly addressed the policy announcement relating to the proposed tax exemption on these interest payments.[25]

The Australian Greens initially indicated that they would like further time to scrutinise the Treasury Legislation Amendment (Unclaimed Money and Other Measures) Bill 2012, and then voted for the Bill in the House of Representatives and the Senate. Of the independents in the House of Representatives, all voted with the Government except Mr Wilkie (Mr Katter was absent).[26] In the Senate, Senator Xenophon voted for the Bill.[27]

Under the arrangements legislated to take effect from 1 July 2013, interest will accrue at the rate of CPI on lost and unclaimed moneys. The proposal to make these interest payments tax-free effectively increases the after-tax return to an individual based on the marginal tax rate they face.

Under current arrangements, prior to money being transferred to ASIC or the ATO, interest accruing on bank accounts is taxed at the relevant marginal rate for those individuals who have provided their tax file number (TFN) to their financial institution and lodged their annual tax return. Where a TFN is not provided, financial institutions will deduct tax at the top marginal rate for interest unless a person falls into an exempt category (such as a pensioner).[28] Once the funds are transferred to ASIC or the ATO no interest is payable so no tax liability arises.

The parliamentary debate about whether individuals would be better or worse off with the proposed changes in the thresholds to define lost or unclaimed moneys in the Treasury Legislation Amendment (Unclaimed Money and Other Measures) Bill 2012, did not directly consider the tax benefits of providing a tax exemption for interest payments. As noted in the Bills Digest for that Bill, whether an individual bank account will be better off being left with the financial institution within the period affected by the changed thresholds or being transferred to the Commonwealth would depend on the interest that accrues to the account and the relevant fees and interest rates that apply.[29]

By exempting interest from tax, an individual is less likely to be disadvantaged under the changed thresholds with the payment of tax-free interest at the rate of CPI. This is because, even before fees are taken into account, the margin between the post-tax benefits of ‘typical’ interest rates paid and the tax-free interest rate based on changes in the CPI narrows or may be negative.

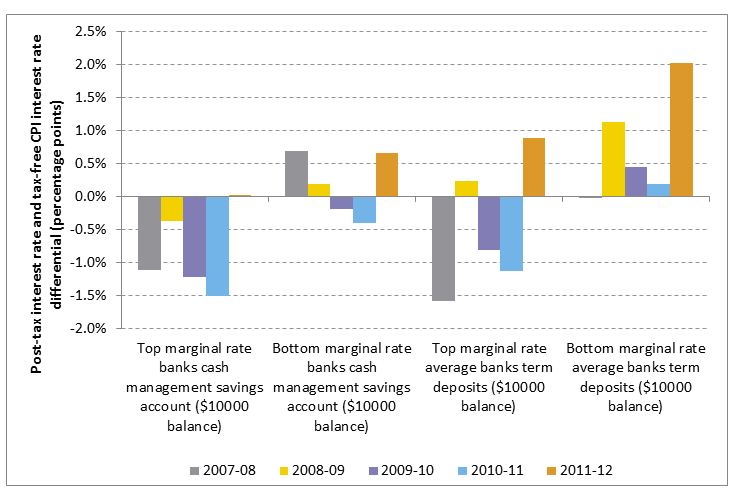

An illustration of the gap is provided in Figure 1, which compares the post-tax interest rates on two different types of accounts for those on the highest and lowest marginal tax rates to the tax-free CPI-adjusted interest rate over the period June 2007 to June 2012.

Figure 1: Comparison between post-tax bank interest rates at the highest and lowest marginal tax rate and the tax‑free interest rate based on changes in the consumer price index, June 2005–June 2012 (percentage points)

Source: Parliamentary Library estimates based on Reserve Bank of Australia, ‘Statistics’, table F4: retail deposits and investment rates, viewed 20 November 2012, http://www.rba.gov.au/statistics/tables/index.html; Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Consumer price index, Australia, September 2012, cat. no. 6401.0, ABS, 24 October 2012, tables 1 and 2, CPI: all groups, index numbers and percentage changes, viewed 20 November 2012, http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/6401.0Sep%202012?OpenDocument and Australian Taxation Office, ‘Individual income tax rates’, ATO website, 24 July 2012, viewed 7 March 2013, http://www.ato.gov.au/individuals/content.aspx?doc=/content/12333.htm&mnu=42590&mfp=001

One conclusion to draw from this illustrative example is that in recent years those in the highest marginal tax rate would have been better off with a tax free CPI adjusted interest rate compared to their post-tax position based on the applicable interest rates in most years. Those individuals facing the lowest marginal rate would have been worse off more often.

The exemption of interest paid on unclaimed and lost money requires amendments to the ITAA 1997 to specify that interest paid under various legislation on these funds is exempt.

For unclaimed money other than superannuation, this is largely achieved through item 34, which specifies the range of payments under the Banking Act 1959, the Corporations Act 2001, the First Home Saver Accounts Act 2008 and the Life Insurance Act 1995 that are exempt from income tax.

The exemption relating to interest on superannuation moneys is more complex. The amendments essentially do this by adding to the existing definitions of the various taxable components of interest on lost superannuation and ‘superannuation benefit’ in the ITAA 1997 so that the interest paid on lost or unclaimed money is included in the tax-free component.

A key provision relating to exempting interest payments on lost superannuation is item 11, which specifies that the interest paid on lost superannuation as specified in the Superannuation (Unclaimed Money and Lost Members) Act 1999 (SUMLA Act) is included in the definition of ‘tax free component’ of a superannuation benefit in the ITAA 1997.

In the case of lost superannuation of former temporary residents, the amendment in item 11 specifies that the tax free component is nil. Also relevant to providing that interest payments are taxable for former temporary residents is item 17, which specifies that interest payments for this group are a taxable component of a superannuation benefit and that these amounts are not taxed in the fund. As a consequence, payments of interest on the unclaimed money of former temporary residents reclaimed after 1 July 2013 are subject to a DASP tax rate of 45 per cent.

Part 1 of Schedule 1 commences the day the Bill receives Royal Assent. Part 2 of Schedule 1 commences on 1 July 2013.

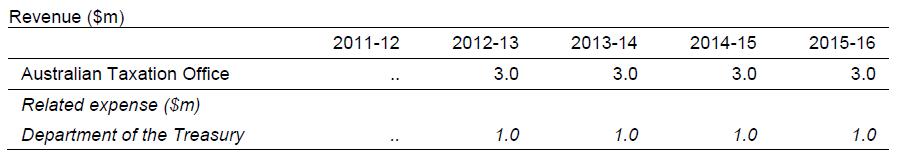

There is no specific information in the Explanatory Memorandum about the cost of exempting from tax the interest paid on lost and unclaimed moneys as the cost was included amongst other costs in the Treasury Legislation Amendment (Unclaimed Money and Other Measures) Bill 2012.[30]

The Treasury’s latest annual statement on tax expenditures, released in January 2013, did not include the proposed tax exemption on interest for lost and unclaimed moneys.[31]

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights (Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed the Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or declared in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act.[32] The Government considers that Schedule 1 is compatible.

Schedule 2 to the Bill amends the FBTAA to align the calculation of airline transport fringe benefits with existing in-house property fringe benefits and in-house residual fringe benefits.

A fringe benefit is a benefit provided by an employer to someone because they are an employee[33], and is generally defined as a benefit not being salary, wage or other cash remuneration, derived from employment. Fringe benefits tax (FBT) is a tax payable by employers when they provide fringe benefits to employees. There are 13 types of fringe benefits subject to fringe benefits tax under the FBTAA, including the airline transport fringe benefit.

An airline transport fringe benefit occurs when employees of airlines or travel agents are provided with free or discounted air travel, on a stand-by basis (that is, where seating is subject to availability and travel is not guaranteed). If the travel is not provided on a stand-by basis, it is taxable as an in‑house property fringe benefit or an in-house residual fringe benefit. In practice, this means the current airline transport fringe benefits system is messy and based on a number of valuation methods (Table 2).

Table 2: Taxable value of airline transport fringe benefits

|

Travel type

|

Taxable value

|

|

Stand-by travel on a scheduled domestic passenger air service the benefit provider operates.

|

37.5 per cent of the lowest publicly advertised economy airfare the provider charges for travel:

- at or about that time and

- for travel over that route.

|

|

|

Stand-by travel on a scheduled international passenger air service the benefit provider operates.

|

37.5 per cent of the lowest published airfare the provider charges for travel over that international route.

|

|

Stand-by travel not on a scheduled domestic or international passenger air service the provider operates.

|

37.5 per cent of the lowest publicly advertised economy airfare a carrier charges for travel:

- at or about that time and

- for travel over that route.

|

|

Stand-by travel on a combination of scheduled domestic or international passenger air services where there is no:

- scheduled passenger air service the provider operates over that route at or about that time and

- carrier operating a scheduled passenger air service over that route at or about that time.

|

37.5 per cent of the lowest combination of publicly advertised economy airfares carriers charge for travel:

- at or about that time and

- for travel over that route.

|

|

Any other case

|

75 per cent of the market value, at or about that time, for travel over that domestic or international route.

|

Source: ATO, ‘Airline transport fringe benefits’, ATO website, viewed 5 March 2013, http://www.ato.gov.au/businesses/content.aspx?menuid=0&doc=/content/52025.htm&page=3&H3

Virgin Australia announced its support of the changes as they will ‘modernise and simplify the current legislation’, and indicated that Treasury had taken time ‘to understand Virgin Australia’s business needs’.[34] Qantas similarly indicated that its concerns had also been addressed.[35]

PricewaterhouseCoopers noted that while the proposed changes will lead to compliance savings for airlines, there may be increased tax burdens for travel agents. This is because travel agents are more likely to include airline transport fringe benefits within salary sacrifice arrangements.[36] Concessional treatment for in-house fringe benefits accessed through salary sacrifice arrangements will be removed by the Tax Laws Amendment (2012 Measures No. 6) Bill 2012 which, at the time of writing, was still before the Parliament.[37]

The commencement of Schedule 2 is reliant on the commencement of Schedule 7 to the Tax Laws Amendment (2012 Measures No. 6) Bill 2012, which removes concessional treatment for in‑house fringe benefits accessed through salary packaging arrangements.[38] As set out above, this Bill is still before Parliament.[39] The effect of the amendments included in both of these Bills will be to remove concessional treatment of airline transport fringe benefits that are included in salary sacrifice packages. This is because the Bill repeals Division 8 of Part III of the FBTAA (item 1 of Schedule 2) that identifies airline transport fringe benefits as a separate type of fringe benefit. Instead, airline transport fringe benefits are included as an in-house property benefit (items 2 to 4) and an in-house residual fringe benefit (items 5 to 8), which are the same types of benefits that will have their concession removed (that is, taxed at the notional value of the benefit at the comparison time) if the benefit was provided to the recipient under a salary packaging arrangement. It is also worth noting that while the amendments made by the current Bill apply retrospectively to fringe benefits provided since the time of the announcement on Budget night 8 May 2012, the salary sacrificing amendments only apply to: new salary packaging arrangements made on or after 22 October 2012, existing salary packaging arrangements that undergo material change on or after 22 October 2012, and existing unchanged salary packing arrangements from 1 April 2014.

If the airline transport fringe benefit was not provided under a salary packaging arrangement, then the existing rate of 37.5 per cent will continue to apply, although it will be calculated using simpler methods. Proposed paragraphs 42(1)(ab), 48(ab) and 49(ab) define the taxable value of an airline transport fringe benefit as ‘an amount equal to 75 per cent of the stand-by airline travel value of the benefit at the time the transport starts’[40] less the employee contribution. Item 27 of Schedule 2 repeals the current method of calculating ‘stand-by value’ which is included in the list of definitions in subsection 136(1) of the FBTAA. Item 26 inserts the following new definition of ‘stand‑by airline travel value’ into subsection 136(1) of the FBTAA:

- where the transport is on a domestic route, the stand-by airline travel value is 50 per cent of the carrier’s lowest standard single economy airfare for that route as publicly advertised during the year of tax and

- where the transport is on an international route, the stand-by airline travel value is 50 per cent of the lowest of any carrier’s standard single economy airfare for that route as publicly advertised during the year of tax.

Thus, the proposed tax value for an airline transport fringe benefit is 75 per cent of 50 per cent of the airfare (or 37.5 per cent of the value of the airfare).

The simplified method of calculating the value of the airfare is of greater significance in terms of the compliance burden of the existing law. Under the proposed definition of ‘stand-by airline travel value’, employers will no longer need to track the date on which travel occurred, as the lowest publicly advertised fare for that route during the year of tax may be used. Further, employers will not have to distinguish between scheduled and unscheduled passenger services. Lastly, the carriers that can be used for valuations is simplified so that the lowest fare of the route charged by the carrier that provided the transport is used for domestic routes, and the lowest fare of any carrier for the route may be used for international routes.

The proposed definition of ‘airline transport fringe benefit’ inserted by item 15 into subsection 136(1) of the FBTAA maintains the current distinction between free or discounted travel provided on a stand-by basis, and travel that is not provided on a stand-by basis. This means that travel that is not provided on a stand-by basis will continue to be subject to in-house fringe benefits valuation (75 per cent of the notional value of the benefit at the comparison time).

The proposed definition of ‘comparison time’ inserted by item 16 into subsection 136(1) of the FBTAA changes the comparison time for an airline transport fringe benefit to when the transport starts (rather than when it is provided).

The remaining items that amend subsection 136(1) repeal definitions no longer required after the repeal of the airline transport fringe benefits Division (Division 8 of Part III of the FBTAA).

The Explanatory Memorandum states that the financial impact of the changes proposed in Schedule 2 are unquantifiable. However, the changes proposed in the 2012–13 Budget announcement had a forecast increase in revenue of $12 million over the forward estimates period, as well as an additional $4 million in GST collections for the states (Table 3).

Table 3: Revenue forecast for original proposals to amend airline transport fringe benefits

Source: Australian Government, Budget measures: budget paper no. 2: 2012–13, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 2012, p. 25, viewed 5 March 2013, http://www.budget.gov.au/2012-13/content/bp2/download/bp2_consolidated.pdf

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights (Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act, the Government has assessed the Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or declared in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The Government considers that Schedule 2 is compatible.[41]

The Sustainable Rural Water Use and Infrastructure Program (SRWUIP) funds projects that increase water use efficiency in rural Australia, with a particular focus on substantial, long-term and lasting changes. It is part of the Australian Government’s Water for the Future initiative and involves a variety of projects, ranging from the Strengthening Basin Communities program through to specific pipeline projects.[42]

Under the program, payments may be made to project participants in the form of a subsidy (which would be included in the participant’s assessable income) and/or as a transfer of water rights (which would be taxed as a capital gain). Expenditure by the participant on infrastructure improvements is deductible over time. This has led to a timing mismatch for the deductibility of certain payments. The proposed amendments address this by allowing a recipient of SRWUIP funding to choose to treat SRWUIP payments as non-assessable non-exempt (NANE) income and disregard any capital gains or losses, but also lose the deductibility of infrastructure payments. Alternatively, an entity may maintain the current arrangements where payments are taxable, which may be beneficial for Capital Gains Tax (CGT) deductions.

Changes to the way payments are taxed under the SRWUIP were first flagged on 18 February 2011.[43] The Treasury then released an Exposure Draft on the tax treatment of water infrastructure improvement payments on 13 July 2012, with submissions closing on 13 August 2012.[44] The consultation received ten public submissions and two confidential submissions.[45] The legislation was significantly altered as a result of the consultation.

A number of submissions on the Exposure Draft raised concerns that the change in tax treatment of SRWUIP payments will benefit some taxpayers and be detrimental to other taxpayers, the effect of which is worsened by the retrospective nature of the amendments. Further, the Institute of Chartered Accountants (ICAA) noted that taxpayers adversely affected by these amendments were more likely to be small irrigators, rather than large irrigators:

Specifically those individual irrigators who have sold water shares to the Commonwealth as part of a SRWUIP program and those who have received a qualifying water infrastructure improvement payment and are eligible for the Small Business CGT Concessions may be adversely affected by the proposed arrangement.

… for large irrigators, receipt of payment under SRWUIP would generally be taxable in the year they are received, either as ordinary income or as a subsidy. At a high level, the large irrigators would appear to benefit from the proposed arrangement.[46]

These concerns were mirrored by other submissions on the Exposure Draft. To address this, the current amendments enable irrigators to choose which tax treatment of payments under the scheme applies to them.

Item 8 of Schedule 3 inserts five new sections into the ITAA 1997: proposed section 59-65 allows an entity to choose to have a payment under a SRWUIP program considered NANE income; proposed section 59-67 defines a direct and indirect SRWUIP payment; proposed section 59-70 requires the Water Secretary to keep a list of SRWUIP programs and publish them on the Water Department’s website; proposed section 59-75 requires the Water Secretary to notify the Commissioner of Taxation about any SRWUIP payments the Commonwealth seeks to recover; and proposed section 59-80 allows the amendment of tax assessments in the event that changes occur under the other proposed sections. Importantly, under proposed section 59-65, a choice made by an entity to treat SRWUIP payments as NANE income applies to all amounts paid by the Commonwealth under that program and is irreversible.

Item 11 inserts proposed paragraphs 118-37(1)(ga) and (gb) into the list of ‘exempt or loss-denying transactions’ in the ITAA 1997 so that any capital gain or capital loss made from a CGT event in relation to a SRWUIP payment, or water entitlement derived from a SRWUIP payment, that is NANE income under proposed section 59-65 is disregarded. Thus, once a choice has been made for SRWUIP payments to be NANE income, CGT events in relation to those payments will be automatically disregarded.

Under proposed section 26-100 of the ITAA 1997 (inserted by item 3) the choice to make SRWUIP payments NANE income will also mean that SRWUIP expenditure in relation to those payments will not be deductible. Proposed subsection 26-100(2) defines SRWUIP expenditure as any expenditure incurred to satisfy an obligation under an arrangement under a SRWUIP program and that is reasonably expected to be matched by a SRWUIP payment as part of the program.

Reference to proposed section 26-100 is inserted into provisions of the ITAA 1997 dealing with the cost of CGT assets so that SRWUIP expenditure is not included in the cost of the asset for tax purposes. Item 4 inserts reference to proposed section 26-100 into subdivision 40-C so that the cost of a depreciating asset is reduced by the portion of it that is SRWUIP expenditure covered by the proposed section (and therefore not deductible). Items 5 and 6 prevent SRWUIP expenditure covered by proposed section 26-100 from being counted as capital expenditure in relation to a water facility. Item 9 inserts reference to proposed section 26-100 into section 110-38 so that SRWUIP expenditure covered by the proposed section does not form any part of a CGT asset’s cost base. Likewise, item 10 inserts reference to proposed section 26-100 into the general rules about the reduced cost base of a CGT asset so that expenditure under the proposed section does not form part of the reduced cost base. Thus, SRWUIP expenditure on a CGT asset that is matched with a SRWUIP payment where a choice has been made to treat it as NANE income cannot be deducted when a CGT event occurs.

The amendments proposed in Schedule 3 apply retrospectively to payments made by the Commonwealth under a SRWUIP program on or after 1 April 2010.[47] Schedule 3 commences the day the Bill receives the Royal Assent.

The Explanatory Memorandum states on page 5 that the proposed changes in Schedule 3 will have a negative impact on the first two financial years from 2012–13, but will have a positive financial impact from 2014–15. Over the forward estimates, the amendments will have a net financial impact of –$45 million:

Table 4: Financial impact of Schedule 3

|

2012–13

|

2013–14

|

2014–15

|

2015–16

|

|

-$35m

|

-$30m

|

$5m

|

$15m

|

Source: Explanatory Memorandum, p. 5.

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights (Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act, the Government has assessed the Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or declared in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The Government considers that Schedule 3 is compatible, and that it promotes the right to health.[48]

An SMSF is a small superannuation fund with one to four members where the members actively participate in the fund’s management. In contrast to large superannuation funds, which are regulated by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), SMSFs are subject to regulation by the ATO.

As at 30 June 2012, there were 478 263 SMSFs managing around 30 per cent of total superannuation assets in Australia.[49] There has been significant and sustained growth in the number of SMSFs in recent years, with around 35 000 new SMSFs registered in 2011–12.[50]

As with all superannuation funds, the overriding principle governing the operation of a fund is the ‘sole purpose test’, which essentially provides that savings should be invested for the sole purpose of providing retirement savings (together with certain approved ancillary benefits) and not for providing current‐day benefits.[51]

The sole purpose test is supported by a range of rules about superannuation fund investments and operations. These include rules prohibiting the acquisitions of certain assets (subject to specific exceptions) from related parties in some circumstances and making and maintaining investments on an arm’s-length basis.[52]

Importantly, the generic rules relating to prohibiting the acquisition of certain assets from related parties in some circumstances have an additional exception for SMSFs, if the asset is ‘real business property’ of the related party acquired at market value.[53] Several other rules also have specific application to SMSFs, such as investing in collectables and personal use assets and limits on borrowing.[54]

While the reporting of contraventions of the SIS Act by SMSF auditors to the ATO is limited to around two per cent of SMSFs each year, breaches of rules relating to the sole purpose test, in‑house assets, investing at arm’s length, and acquisition of assets from related parties accounted for around one-third of reported breaches over the period 2005 to 2012.[55]

Cooper Review

The Cooper Review, conducted over the period 2009–2010, examined a range of issues relating to SMSFs.[56] While the Review’s overall conclusion was that SMSFs are ‘largely successful and well‑functioning’, it made a number of recommendations related to SMSF investment activities. The key recommendations were that:

- no in-house investments be allowed by SMSFs (Recommendation 8.12)

- legislation relating to acquisitions and disposals between related parties in SMSFs (but not APRA‐regulated funds) should be amended so that, either:

– where an underlying market exists, all acquisitions and disposal of assets between SMSFs and related parties must be conducted through that market or

– where an underlying market does not exist, acquisitions or disposals of assets between related parties must be supported by a valuation from a suitably qualified independent valuer (Recommendation 8.13)

- legislation in relation to SMSFs should be amended so that the acquisition of collectables and personal use assets by SMSF trustees be prohibited and that SMSFs that own collectables or personal use assets be provided a five year transition period to dispose of these assets (Recommendation 8.14)

- SMSFs should be required to value their assets at net market value (Recommendation 8.16) and

- the ATO, in consultation with industry, should be required to publish valuation guidelines to ensure consistent and standardised valuation practices (Recommendation 8.17).[57]

The Government’s initial response to the Cooper Review, announced in December 2010, was to not support the recommendations relating to in-house asset rules and the acquisition of collectables and personal use assets but to support the others, with a commitment to further consultation on their implementation.[58]

Further consultation on these measures, undertaken by the Stronger Super Peak Consultative Group between February 2011 and May 2011 further informed the implementation of the recommendation relating to the acquisition and disposal of assets between related parties. The consultation report highlighted some disagreement on whether legislative action was required, but the majority view was that Recommendation 8.13 of the Cooper Review should be implemented.[59]

The Government’s final response, announced in September 2011, supported this majority view, noting that the Government ‘will legislate to require related party transactions to be conducted through the market where one exists. If no market exists, the transaction must be supported by a valuation from a suitably qualified independent valuer’.[60]

Draft legislation

Draft legislation for the measure was released by the Treasury in late 2012, with submissions closing on 16 January 2013.[61] Where relevant, views expressed in the nine submissions on the draft Bill are noted below.

In their dissenting report for the Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services inquiry into the Bill, the Coalition members of the Committee indicated that they do not support Schedules 4 of the Bill, recommending that it be removed.[62] Opposition to Schedule 4 is largely based on a view that the measures represent an unnecessary regulatory.[63]

The peak body representing the SMSF sector, the SMSF Professionals Association of Australia (SPAA), generally supports the proposed measures, considering that they ‘take a sensible approach to transactions between SMSFs and related parties, with independent valuations being required where an asset is acquired from or disposed to a related party’.[64] One of the SPAA’s main concerns is that APRA-regulated funds should also be subject to the requirements.[65]

Both the Association of Superannuation Funds of Australia (ASFA) and the Australian Institute of Trustees (AIST) support the proposed measures, with ASFA noting that the measures ‘will add rigour to the process and act as a mitigation to the risk of transaction date and asset value manipulation to benefit the SMSF or a related party’.[66]

The ICAA and CPA Australia do not support the proposed measures.[67] The ICAA noted that:

… we do not believe that a systemic problem exists that warrants the introduction of these new measures. Furthermore, we believe that other measures, such as clearer parameters on how such transactions were undertaken would be more appropriate to ensure that trustees were undertaking these transactions correctly. Other parts of the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 already contain requirements for all SMSF transactions to be conducted on an arm’s length basis.

This, together with heightened standards of audits being undertaken as a result of the new SMSF auditor registration regime would have given a better result for SMSF trustees and given assurance around any “potential abuse” as suggested by the Cooper review panel in their report.[68]

The Bill proposes to retain the existing arrangements for the acquisition of certain assets from related parties for non-SMSF superannuation funds and to create a specific separate regime for SMSFs.

Section 66 of the SIS Act sets out the circumstances in which superannuation funds may acquire assets from related parties. Subsection 66(1) provides a general prohibition of such acquisitions. Exceptions to this general rule (that is, the circumstances when assets may be acquired from related parties) are then set out in subsections 66(2), (2A) and (2B). Item 7 of Schedule 4 amends the general prohibition on the acquisition of assets from related parties contained in subsection 66(1), so that it no longer applies to SMSFs.

Item 13 inserts proposed section 66A, which provides for the SMSF-specific arrangements prohibiting acquisitions of certain assets from a related party of the fund. The proposed arrangements largely retain the existing exceptions that apply to SMSFs under section 66, including those relating to real business property. The proposed arrangements also retain the existing exceptions in the event of a breakdown in relationships or due to changes in the number of trustees. However, the key difference between the existing regime and proposed arrangements is that:

- the proposed arrangements relate to all acquisitions from a related party while the existing arrangements relate to those that are intentionally acquired

- the exception applying to listed securities will apply only if acquired ‘in a way prescribed by regulations’ and

- the exceptions applying to assets acquired through a merger between regulated funds and in‑house assets require the assessment of market value ‘as determined by an independent qualified valuer’.

Several industry bodies including the ICAA and SPAA noted the proposed change would cover all acquisitions from related parties for SMSFs compared to the intentional acquisition covered by the current provision, which would apply to the non-SMSF sector under the proposed arrangements.[69] Both of these groups supported a change to the provision so that only the intentional acquisition of assets by SMSFs would be covered.[70]

Neither the SIS Act nor the Bill include a definition of an ‘independent qualified valuer’. However, the Explanatory Memorandum notes that:

A valuer may be qualified either through holding formal valuation qualifications or by being considered to have specific knowledge, experience and judgment by their particular professional community. This may be demonstrated by being a current member of a relevant professional body or trade association.

The valuer must also be independent. Therefore, the valuer cannot be a member of the fund or a related party of the fund. They should be impartial, unbiased and not be influenced or appear to be influenced by others.

Independent and impartial valuation services are also offered by the Australian Valuation Office.[71]

In its submission on the draft legislation, the SPAA considered that further flexibility was required in cases where no individual has the specific knowledge, experience and judgement necessary to be considered a qualified valuer.[72] The SPAA noted that:

To overcome these issues, consideration should be given to removing the requirement to obtain a qualified independent valuation in situations where the SMSF trustees, after making reasonable attempts, has been unable to find a qualified independent valuer. In these situations the acquisition or disposal of the asset at market value should suffice. The explanatory material could be used to explain and clarify what would constitute “reasonable attempts” for this purpose.[73]

The particular methodology governing transactions involving listed securities will be detailed in regulations, with penalties applying for breach of these regulations (proposed paragraphs 66A(3)(a) and 66B(3)(a)). In commenting on the draft legislation (the wording of which is unchanged in the Bill), commentators were unclear as to whether off-market transfers of shares may still be available as an option to SMSFs, however it would seem logical that listed securities would need to be transferred on-market pursuant to these regulations given the potential for valuation errors that exists in off market transfers.[74]

Proposed section 66B inserted by item 13 introduces new rules for SMSF trustees and investment managers when disposing of assets to related parties. Proposed section 66B corresponds to proposed section 66A, in that it contains a general prohibition on a trustee or investment manager disposing of an asset to a related party of the fund, but then sets out exceptions where disposal of certain assets by SMSFs to related parties is permitted. These exceptions largely mirror the requirements relating to the acquisition of assets by SMSFs from related parties for listed securities, money and assets disposed at market value as determined by a qualified independent valuer—apart from the exception that applies to assets that are ‘collectable and personal use assets’ that have an existing regulation in force.[75]

Proposed section 66C introduces a prohibition on schemes which avoid the operation of these new rules. This provision is similar to the existing provision applying to the acquisition of assets by superannuation funds (subsection 66(3)).

The proposed arrangements relating to the acquisition and disposal of assets by SMSFs with related parties in proposed sections 66A and 66B include civil penalty provisions, which are added to the existing list of civil penalty provisions in section 193 by item 14. Part 21 of the SIS Act provides for civil and criminal consequences for contravening a civil penalty provision. The maximum penalty that may be imposed by a court that makes a civil penalty order is 2000 penalty units (subsection 196(3) of the SIS Act).[76] In addition, if the contravention of a civil penalty provision involves a person either:

- dishonestly, and intending to gain, whether directly or indirectly, an advantage for that, or any other person or

- intending to deceive or defraud someone

then the person is guilty of a criminal offence that is punishable by a maximum sentence of five years imprisonment (subsection 202(1)).

In addition to the civil penalty provisions, administrative penalties are also proposed in Part 2 of Schedule 4. This reflects the proposed introduction, in the Superannuation Legislation Amendment (Reducing Illegal Early Release and Other Measures) Bill 2012, of a more comprehensive regulatory framework, including the ability to issue rectification and education directions and to impose administrative penalties for certain contraventions. [77] As the administrative penalties proposed in Part 2 of Schedule 4 will fit within the broader regulatory framework to be introduced by the Superannuation Legislation Amendment (Reducing Illegal Early Release and Other Measures) Bill 2012, they will commence immediately after the relevant provision of that Bill. Under the proposed administrative penalties, a trustee or director of a corporate trustee will be liable to an administrative penalty of 60 penalty units for each contravention. This may be contrasted with the maximum civil penalty of 2000 penalty units that may be imposed should a civil penalty order be made by a court.

The ICCA considers that the level of administrative penalties specified for a breach of the provisions relating to the acquisition and disposal of certain assets by SMSFs and related parties—as specified by item 19 to be 60 penalty units—is inappropriate. The ICAA noted that:

Notwithstanding the Commissioner of Taxation will have powers of remission where penalties are imposed, a maximum fine of over $10,000 is particularly harsh. We believe the number of penalty units should be at least half this amount. At this level, the fine is still significant enough to act as a deterrent to trustees undertaking inappropriate related party transactions but not so great as to overly impact on retirement savings.[78]

Part 1 of Schedule 4 commences on 1 July 2013. As set out above, the commencement of Part 2 of Schedule 4 is reliant on the commencement of Schedule 3 to the Superannuation Legislation Amendment (Reducing Illegal Early Release and Other Measures) Bill 2012.

The Explanatory Memorandum notes that financial impact of the proposal is ‘nil’.[79]

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights (Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act, the Government has assessed the Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or declared in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The Government considers that Schedule 4 is compatible.[80]

As set out above, however, the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights has sought clarification from the Treasurer about whether the penalties imposed by Schedules 4 and 7 may be characterised as criminal for the purposes of articles 14 and 15 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.[81]

Current company tax arrangements provide that nominal tax losses can be carried forward indefinitely subject to some integrity rules. However, there are no provisions that provide for companies which have previously made profits to claim back the tax paid. This refunding of previous tax paid when a loss is incurred is described as ‘loss carry-back’ and corrects the existing asymmetry where only previous losses are allowed to be carried forward and offset against future profits.

As part of the 2012–13 Budget, the Government announced that a limited form of loss carry-back would be implemented that provides for:

- eligibility to be restricted to entities that are taxed like companies and be limited to revenue losses only

- a one-year loss carry-back applied in 2012–13, where tax losses incurred in that year can be carried back and offset against tax paid in 2011–12

- for 2013–14 and later years, tax losses can be carried back and offset against tax paid up to two years earlier and

- maximum carry-back of previous tax losses in a year of $1 million or a company’s franking account balance (whichever is lower)—providing for a maximum cash benefit of up to $300 000 a year.[82]

The Budget announcement was made in association with the abandonment of a general reduction in the company tax rate from 30 per cent to 29 per cent in 2013–14 (and from 2012–13 for small businesses). The Government’s rationale for not proceeding with the proposed company tax rate cut was that the likely rejection of the proposal in the Parliament by the Coalition and Australian Greens would deny the community the benefits flowing from the resources boom and that savings available from not proceeding with the company tax rate cut could be redirected through other measures.[83]

Partly to address business concerns about abandoning the company tax rate cut, the Government has instead proposed a limited form of tax loss carry-back.[84]

Tax loss carry-back is part of business taxation arrangements in a number of countries, although its application differs across jurisdictions by the types of entities to which it applies, thresholds relating to the maximum amount of tax carry-back, and the number of years of tax paid that can be accessed (Table 5). Compared to other countries where tax loss carry-back applies, the proposed scheme in Australia appears to be less generous in restricting eligibility to companies only.

Table 5: International loss carry-back systems, selected countries

|

Country

|

Loss carry-back arrangements

|

|

Canada

|

3 years, permitted for unincorporated businesses

|

|

France

|

1 year (recently reduced from 3 years) and subject to a €1 million annual cap

|

|

Germany

|

1 year (extends to sole traders and partnerships), capped at €0.5 million per year

|

|

Ireland

|

1 year (permitted for unincorporated businesses), 3 years if business ceases trading

|

|

Netherlands

|

1 year (3 years for 2009, 2010 and 2011 losses), capped at €10 million per year

|

|

Norway

|

No (temporarily introduced for 2 years if business ceases trading or for losses in 2008 and 2009), capped at NOK 20 million per year

|

|

Switzerland

|

No (one canton does allow 1 year carry in respect of local taxes)

|

|

United Kingdom

|

1 year (permitted for unincorporated businesses, 3 years if business ceases trading and temporarily extended to 3 years for losses incurred in 2008 and 2009) but subject to a £50 000 cap

|

|

United States

|

2 years (permitted for unincorporated businesses up to 5 years for 2008-09 losses)

|

Source: Business Tax Working Group, Final report on the tax treatment of losses, April 2012, p. 21, viewed 28 February 2013, http://www.treasury.gov.au/~/media/Treasury/Publications%20and%20Media/Publications/2012/Business%20Tax%20Working%20Group%20Final%20Report/Downloads/btwg_final_report_20120413.ashx

Some of the purported benefits of a loss carry-back scheme are:

- it acts as an automatic stabiliser by increasing the cash flows of previously profitable companies during economic down turns—this may in turn make government revenue more volatile, although company tax collections may recover more quickly during economic upturns and

- it removes an inherent bias against risky investments by reducing expected losses for profitable businesses in the early stages of undertaking a possible loss-making investment: the existing wedge between post-tax returns for risky projects and those for safer investments has the effect of reducing investment in more risky proposals relative to a tax system that treats profits and losses symmetrically.[85]

Not all businesses are expected to benefit from loss carry-back, with the measure primarily aimed at assisting companies that experience a temporary setback which results in a period of losses following a period of profits. It is of limited benefit to start-up companies and businesses that typically experience a sustained period of losses before generating a profit (for example, large-scale infrastructure projects).[86]

The proposal for the introduction of loss carry-back in Australia was a recommendation of the Australia’s Future Tax System review, which recommended that companies should be allowed to carry back a revenue loss to offset it against the prior year’s taxable income, with the amount of any refund limited to a company’s franking account balance.[87] Further discussions about the measure at the Tax Forum in October 2011 led the Government to commission the Business Tax Working Group (BTWG), to ‘look at reforms that can increase productivity and deliver tax relief to struggling businesses in our patchwork economy and develop a set of savings options within business tax’.[88]

The BTWG, in its interim report released on 11 December 2011, examined a number of different tax reform options, including a limited form of loss carry-back.[89] The BTWG’s final report, released in April 2012, considered that loss carry-back would be a worthwhile reform in the near term but that the group had not had an opportunity to explore the relative net benefit of loss carry-back compared with other business tax reforms.[90] Most of the design features proposed by the BTWG are reflected in the Budget proposal: eligibility only open to companies, a two-year loss carry-back on an ongoing basis, and a cap of not less than $1 million (or the balance of a company’s franking account).[91]

A regulation impact statement (RIS), released on 18 May 2012, was prepared by the Treasury and assessed by the Office of Best Practice Regulation as adequate.[92] The RIS outlines a range of alternatives available to support small businesses during an economic downturn, including loss carry-back, full loss refundability and introducing a loss uplift factor. The RIS also examined a number of design features of loss carry-back, including the impact on the Budget of different arrangements.[93]

A consultation paper on the Budget proposal was released on 18 July 2012, with submissions due by 6 August 2012.[94] The discussion paper covered the announced design features as well as a range of proposed design arrangements, including integrity rules.[95]

On 23 August 2012, draft legislation for the measure was released for consultation by the Treasury. The Assistant Treasurer noted that further consultation would be undertaken in relation to developing simpler integrity rules.[96]

The Coalition has also proposed a form of loss carry-back in recent years. In April 2009, prior to the Henry Review completing its final report, the Coalition proposed the introduction of limited form of carry-back of tax losses, with the key parameters of the policy being:

- a cap of $100 000 of refunded tax per firm over the past three years

- eligibility limited to firms with at least one employee in each year a refund claim is made, and in each year that tax was previously paid and

- the use of the same integrity rules that currently apply when companies carry forward losses to reduce tax liabilities in future years.[97]

The then Leader of the Opposition, reaffirmed this proposal in his response to the 2009–10 Budget in May 2009.[98]

In their dissenting report for the Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services inquiry into the Bill, the Coalition members of the Committee indicated that they do not support Schedules 5 and 6 of the Bill, recommending that they be removed.[99] Opposition to these schedules is largely due to the Coalition’s opposition to the MRRT and most of the measures linked to it.[100]

The Nationals included a tax loss carry-back measure limited to $100 000 of taxes paid over the past three years as part of their 2010 election policy platform as part of a suite of measures aimed at assisting small business.[101] However, such a policy was not part of the Liberal Party of Australia’s small business or other policies for the 2010 election.[102]

At the time of the announcement of tax loss carry-back for the 2012–13 Budget, the Coalition focused on the issue of the abandonment of the company tax rate cut, citing it as another instance where a commitment had been dumped by the Government.[103] During parliamentary debate on the 2012–13 Budget Bills, only limited attention was paid to the tax loss carry-back proposal, with two Coalition members noting that such a measure would have been more useful in the aftermath of the global financial crisis as proposed by the Coalition at the time and that the restriction to corporate entities only would disadvantage sectors such as tourism and hospitality.[104]

In commenting on the 2012–13 Budget, the leader of the Australian Greens noted that while the Australian Greens would have supported a company tax cut for small business, they would look at the loss carry-back proposed in place of the tax cuts and consult with small business about its operation.[105]

Of the independent members of the House of Representatives, Mr Oakeshott has previously been reported as being in favour of loss carry-back arrangements and Mr Windsor has noted the positive benefits of such a proposal.[106] Mr Wilkie has also noted the benefits of such a proposal.[107]

Following the 2012–13 Budget announcement of the implementation of loss carry-back, the views of the business sector were generally consistent with those of the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (ACCI), which criticised the Government for abandoning the company tax cut given that the quid pro quo mining tax had already been legislated and for a lack of vision in pursuing broader‑based tax reform, but expressed general support for the tax loss carry-back scheme.[108]

While supportive of the proposal, the Council of Small Business of Australia (COSBOA) stated that the process to claim the carry back has to be easy and manageable.[109] COSBOA noted that:

We need to ensure that this decision is not watered down by poor process … Accountants with an understanding of small business, such as those from the Institute of Public Accountants, need to be consulted in the design of the process and it must be easy to use and not costly for the business person, otherwise the process will defeat the purpose.[110]

Schedule 5 of the Bill proposes to insert new Division 160 into the ITAA 1997 and covers the main architecture of loss carry-back.

Eligibility is limited to a refundable tax offset under proposed section 160-10 to those businesses which:

- are a ‘corporate tax entity’[111]

- have paid income tax in either or both of the two previous income years

- have satisfied requirements relating to the lodgement of income tax returns for the current year and each of the preceding five income years and

- have exercised the choice to apply for the tax offset.

One of the benefits of limiting eligibility to businesses structured as companies is administrative simplicity and negligible compliance impact.[112] The final report of the BTWG noted that:

An additional challenge of applying loss carry back to sole traders and individual partners in partnerships is that they face a progressive tax rate schedule and multiple marginal tax rates. This would complicate the calculation of available carry back refunds for businesses as well as decisions around when to utilise the loss carry back system.

Given the difficulties involved in applying loss carry back to trusts generally and the limited benefits for sole traders and partnerships with individual partners relative to the additional costs, the Working Group has concluded that loss carry back should initially be limited to companies and trusts that are taxed as companies. Extending loss carry back to other business structures could be considered further in the future.[113]

The exclusion of businesses that are not incorporated means that only around 700 000 of the 2.1 million businesses operating in Australia at the end of June 2011 were potentially eligible for the tax loss carry-back measure.[114]

The measure is expected to benefit 110 000 companies once design factors, such as having a positive franking account balance and having paid tax in the previous two years, are taken into account.[115] Of these companies, Treasury estimates based on historical company tax return data from 2003–04 to 2009–10 suggest that 90 per cent of the value of the benefit provided will flow to medium, small and micro businesses.[116]

Following the announcement of the proposed measure in the 2012–13 Budget and subsequent consultations, the limit on eligibility to corporate entities only was generally viewed unfavourably by industry groups, despite the additional complexity involved in applying such a regime to unincorporated entities.[117] ACCI noted that:

[W]e do not support the notion that the carry-back of tax loss provision should only apply to companies and other entities taxed like companies as the adoption of more flexible loss arrangement should be equally accessible to sole traders and partnerships. ACCI further notes the relevant loss provisions adopted in the United States, the United Kingdom and Germany also apply to unincorporated businesses.

Equal treatment of losses between different business entities would better serve the policy intent which is to overcome asymmetries and distortions as they currently exist, regardless of the chosen business structure. The latest 2009-10 Taxation Statistics reported that there were 1,043,034 sole traders and 312,616 partnerships that reported at least $1 or more business income; compared to 664,792 entities taxed as companies in the 2009-10 financial year.[118]

Proposed section 160-15 sets out the maximum of the loss carry-back offset that can be claimed using the current applicable corporate tax rate, and specifies that certain losses are excluded through the incorporation of the existing definition of ‘net exempt income’.[119] The maximum amount able to be claimed is the lowest amount of:

- the tax paid in the two previous income years

- the entity’s ‘franking account balance’ at the end of the current year and

- $1 million multiplied by the ‘corporate tax rate’ for the current year (currently $300 000 based on a 30 per cent corporate tax rate).

An entity’s franking account balance is an accounting book entry that records the tax paid on ‘franked’ dividends—where tax has been paid at the company tax rate. The franking account also records the receipt of tax refunds and the distribution of franking credits. The inclusion of this parameter in the maximum amount of tax able to be carried back is largely due to the administrative complexity arising with the payment of a franking deficit tax. One consequence of including this limit is that it may induce some companies to reduce their dividend pay-out rate to increase the reserve of franking credits to support the carry-back of losses.[120]

During consultations on the proposed measure, a number of participants considered that the $1 million limit should be specified in regulations rather than legislation to provide greater future flexibility or to maintain the real value of the cap.[121] The Tax Institute also called for a future review of the appropriateness of the $1 million limit.[122]

Proposed section 160-20 establishes the arrangements for an entity to choose how much of its current year tax loss is to be used for loss carry-back purposes and how this should be apportioned over each of the previous two income years.

Businesses are generally able to carry forward losses of earlier income years subject to meeting integrity rules associated with changes of ownership and business activities. The continuity of ownership test (COT) generally requires that shares carrying more than 50 per cent of all voting, dividend and capital rights be beneficially owned by the same persons at all times during the ownership test period. If a company is unable to satisfy the COT, but can pass the same business test (SBT)—which requires a company to carry on the same business as it carried on immediately before the test time—it is able to carry forward tax losses.[123]

The key reason for loss integrity rules is to remove an incentive for tax driven activities involving entities with losses. In particular, the continuity of ownership test prevents ‘loss trafficking’ — that is, purchasing defunct companies or other companies with losses in order to gain a tax advantage.

Treasury’s consultation paper put forward two main options for integrity rules to apply to loss carry‑back and sought feedback on the appropriateness of these and other alternatives:

- enact rules in Part IVA (the general anti-avoidance rule in the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936) similar to existing sections 177EA and 177EB of that Act, which cover schemes involving the sale of shares that are entered into with the dominant purpose of obtaining an imputation benefit and

- modify or simplify the COT and SBT.[124]

Submissions to the consultation paper on the design of an integrity measure gave different views on whether or not an integrity test was required, and if it was required, what form it should take (Table 6).

Table 6: Industry participant viewed on integrity tests for loss carry-back arrangements

|

Industry group

|

Comments on integrity test |

|

Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry

|

Supportive of integrity rules but implementation should focus on limiting prescription and providing greater simplicity for taxpaying entities

|

|

BDO

|

Should apply current integrity rules but these need to be reviewed/amended. Different rules applying for carry back of losses, to those that apply for carry forward of losses would, potentially, increase the complexity of the Australian tax system.

|

|

|

Not convinced that any specific integrity measures are warranted around loss carry-backs. There are drawbacks in relation to the existing same business test and continuity of ownership regime. Existing tax-avoidance rules in the ITAA 1936 should provide appropriate balance.

|

|

Institute of Chartered Accountants

|

Should not draw on existing integrity rules. Isolated amendment to existing tax-avoidance rules in the ITAA 1936 is ‘similarly misconceived’. Best approach to deal with the possibility of exploitation of the reform is to design a specific integrity measure. Suggests two different approaches.

|

|

Institute of Public Accountants

|

Standalone integrity rules for loss carry back would introduce more compliance and administration cost. A modified version of the existing rules would appear more appropriate

|

| Tax Institute |

The current COT and SBT are complex, unwieldy and costly and should therefore be limited in application rather than extended. The integrity risk is overstated. An extension of the existing tax‑avoidance rules in the ITAA 1936 would provide sufficient protection.

|

Source: Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Submission to Treasury, Improving access to company losses discussion paper, 31 July 2012, viewed 5 March 2013, http://www.treasury.gov.au/~/media/Treasury/Consultations%20and%20Reviews/2012/company%20losses%20access/Submissions/Australian_Chamber_of_Commerce_and_Industry.ashx; BDO, Submission to Treasury, Improving access to company losses, 6 August 2012, viewed 5 March 2013, http://www.treasury.gov.au/~/media/Treasury/Consultations%20and%20Reviews/2012/company%20losses%20access/Submissions/BDO.ashx; Corporate Tax Association of Australia Inc., Discussion paper – improving access to company losses, 8 August 2012, viewed 5 March 2013, http://www.treasury.gov.au/~/media/Treasury/Consultations%20and%20Reviews/2012/company%20losses%20access/Submissions/Corporate_Tax_Association_of_Australia.ashx; Institute of Public Accountants, Submission to Treasury, Discussion paper –‘improving access to company losses’, 6 August 2012, viewed 5 March 2013, http://www.treasury.gov.au/~/media/Treasury/Consultations%20and%20Reviews/2012/company%20losses%20access/Submissions/Institute_of_Public_Accountants.ashx; Tax Institute, Discussion paper: improving access to company losses, op. cit.; Institute of Chartered Accountants, Institute of Chartered Accountants, Submission to Treasury, Discussion paper, improving access to company losses of July 2012, op. cit.

The proposed integrity measures included in the draft Bill applied a modified COT and SBT to loss carry-back.[125] In releasing the draft Bill, the Assistant Treasurer and Minister for Small Business conceded that further changes may be required:

Some submissions [to the consultation paper] argued for applying different rules for loss carry-back than loss carry-forward but the consultation did not result in a sufficiently developed alternative.

As a result, the Assistant Treasurer will also oversee targeted consultation to identify and further develop alternative integrity rules for loss carry-back prior to legislation being introduced into Parliament. If this consultation can identify a simpler approach that adequately addresses integrity risks, the Government will adopt it.[126]

In commenting on provisions of the draft Bill, Pitcher Partners noted that ‘the proposed integrity rules … are too unwieldy for the middle market. We believe that a specific integrity rule is required that is simple for taxpayers in the middle market to understand and implement’.[127]

Proposed section 160-35 provides for a specific integrity rule that applies to the loss carry-back arrangements. The proposed integrity rule incorporates elements of changes in both ownership and business activity. According to the Explanatory Memorandum:

The specific integrity rule for loss carry-back denies a corporate tax entity a loss carry-back tax offset it would otherwise be entitled to where there has been a change in the control of the entity arising from a disposition of membership interests and, considering all of the relevant circumstances, one or more parties entered into a scheme to obtain the tax offset.[128]

The proposed integrity rule appears to be simpler than the existing COT and SBT tests in relation to carry forward losses of earlier income years, but there are no clear objective tests for determining whether an entity is entitled to the carry-back tax offset. However, the Explanatory Memorandum includes a number of hypothetical cases that may assist in the interpretation of the integrity rule.

Item 6 of Schedule 5 provides that loss carry-back applies to assessments for the 2012–13 income year and later years. A transitional arrangement in proposed section 160-5 specifies that an entity’s loss carry-back component for the 2010–11 income year is nil—thereby providing only for a one-year carry-back for the 2012–13 income year only, before moving to a two-year carry-back period.

The majority of measures in Schedules 5 and 6 commence the day after the Bill receives Royal Assent. Divisions 2 and 3 of Part 2 of Schedule 5 commence on 1 July 2013. The commencement of item 35 of Schedule 5 is reliant on the commencement of item 5 of Schedule 1 to the Tax Laws Amendment (Countering Tax Avoidance and Multinational Profit Shifting) Act 2013.[129]

The Explanatory Memorandum notes that the proposal has an expected cost to the Budget of $700 million over the period 2012–13 to 2015–16 (Table 7).[130]

Table 7: Financial impact of tax loss carry-back, 2012–13 to 2015–16 ($ million)

|

Year

|

2012–13

|

2013–14

|

2014–15

|

2015–16

|

Total

|

|

Impact on revenue ($m)

|

-

|

-$150

|

-$250

|

-$300

|

-$700

|

Source: Explanatory Memorandum, p. 7.

The Treasury’s latest annual statement on tax expenditures, released in January 2013, included proposed loss carry-back arrangements as a new tax expenditure, with the same estimated financial impact.[131]

The administration cost of implementing the proposal was estimated to be $13.9 million (including $4.7 million of capital expenditure), which was to be paid to the ATO.[132]

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights (Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act, the Government has assessed the Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or declared in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The Government considers that Schedules 5 and 6 are compatible.[133]

Part 1 of Schedule 7 seeks to make a number of changes to the taxation arrangements that apply to the profits-based minerals resource rent tax (MRRT) and petroleum resource rent tax (PRRT) arrangements. The amendments were released as an Exposure Draft on 15 August 2012.[134] No submissions were published as part of the consultation process.

Background

Legislation to support the MRRT passed the Parliament on 19 March 2012 and was given Royal Assent on 29 March 2012.[135] It first applied to profits earned on liable projects from 1 July 2012, with the first quarterly payment due by 21 October 2012.[136]

The revenue estimates from the MRRT have been revised down significantly from those made in November 2011 at the introduction of the MRRT package of Bills, when the MRRT was expected to raise $3.7 billion in 2012–13.[137] The latest estimates from the 2012–13 Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook in October 2012 were that the MRRT would raise a net $2.0 billion in 2012–13 and $8.1 billion over the four years to 2015–16. However, payments to date for the first two quarters of the 2012–13 financial year of $126 million suggest that the MRRT may not meet expectations.[138]