Papers on Parliament No. 46

December 2006

Prev | Contents | Next

Advice Opinion given or offered as to action; counsel; information given; news; formal notice of a transaction.

Oxford Dictionary

Introduction

This paper analyses the various sources and processes involved in providing policy advice to Australian governments with particular attention to developments at the Commonwealth level. Both internal sources of advice such as the public service, and the growing array of external advisory bodies such as parliamentary committees, royal commissions, public inquiries and ministerial staff and consultants are assessed.

There are several key issues about advice to governments and the advisory processes that need to be discussed.

First, the Australian advisory system, especially at the national level, has become more diverse and complex. Whether this is a function of the growing complexity of public policy issues and/or the desire for wider ranges of policy advice by elected officials is one consideration that needs assessment. It is probably the result of both pressures. Not that long ago, the former director of the now defunct Commonwealth Futures Commission, Sue Oliver, lamented that:

Australia … has a closed, non-porous policy making system compared with, for instance, the United States and its use of congressional committees. Congressional committees provide a stage for lobby groups and think tanks to bring their ideas, research and advocacy within the political process. No such formal process exists in Australia at government level for reaching out for new ideas or, at the very least seeking to achieve co-operation between … interest groups.[1]

The argument being that Australia was supposed to have a very executive dominated political system, that governments at both federal and state level in Australia relied heavily on their departments for their advice and that decision making was made behind closed doors with key interest groups having special access.

Given such views were being expressed long after the many initiatives of the Whitlam Labor Government (1972–75) that were largely sustained by successive commonwealth administrations and adopted to some extent across the states, such as increased numbers of ministerial staff recruited from outside the public service, greater use of external consultancies, expansion of the use of public inquiries and the establishment of many new special advisory commissions, this view needs to be seriously challenged.

Also, the Australian advisory system was not as closed as many thought even before the election of the Whitlam Government. Dr H.C. Coombs, long time head of the Reserve Bank of Australia and senior advisor to many Commonwealth governments observed that: ‘although it is the convention … prime ministers should and almost invariably do rely upon the head of their department and his colleagues to inform and advise them,’ this is, ‘as a rule as much honoured in the breach as in the observance.’[2]

Further, the 1976 Royal Commission into Australian Government Administration (Coombs Commission) highlighted the extensive range of advisory sources that had long been available to government.[3] They were considerably broader and more numerous than suggested by Oliver and others.[4]

Also, Australian governments have long established special statutory and permanent advisory bodies—the Tariff Board and its successors like the Industries Assistance Commission spring to mind as does the Universities Commission established by the Menzies Government during the late 1950s.

Australian Commonwealth and state governments, like their counterparts in the United Kingdom, Canada and New Zealand, have also long used public inquiries—those ad hoc, temporary, task forces, committees, working parties, commissions and royal commissions, composed of members drawn from mostly outside of government. Importantly, these bodies employ extensive public consultation processes to collect information and hear witnesses. They also publicly release their reports and much of the underpinning evidence, unlike many government/departmental reports. Nevertheless, public inquiries as a distinct system and ongoing part of the policy advisory process remain both a neglected area of study and an unrecognised part of the executive advisory process.

Altogether, these different institutions are anything but a non-porous system of advice. Of course, the Australian policy advisory system like the Westminster system from which it was developed, has always been more open and diverse than its formal arrangements and conventions seemed to suggest. B.C. Smith observed about the British system of advisory processes in 1968 that:

It has long been common practice in British government … to establish formal means by which ministers and governments can seek opinion and advice and information from outside the Civil Service … it is not easy to establish the precise numbers of advisory bodies … because there is no single definition of an advisory body.

The other aspect about advice is appreciating what it is. Many think that advice is just information, and certainly there are agencies, like the Australian Bureau of Statistics and to some extent the Australian Institute of Criminology, that collect data and provide minimal commentary on the information provided. These bodies give integrity to the information collected. But advice, as discussed later in this paper, is more than data collection and simple information provision. While it does involve collecting data, for such information to constitute advice it has to be processed considerably. This involves sorting, filtering, categorising, interpreting, understanding, selecting, analysing, and eventually, somewhere along the line, someone has got to give recommendations and thus advice.

There are many opportunities in these various processes for information to be distorted and for poor advice to be prepared. For instance, if the basic raw data is poorly ‘harvested’ then subsequent analysis, no matter how good, will be inaccurate. Due diligence is needed to ensure the veracity of both the methods of collecting information and its processing. Sometimes, as recent examples overseas highlight[5] governments do not seek to inform themselves of the basic core information and data before making decisions. Advice tendered can be so ideologically driven that ‘facts’ are diverted, perverted or just ignored.[6] Of course, advice and information, sometimes called ‘intelligence’ can get distorted by hierarchical structures in organisations[7] and within various advisory committees—the ‘groupthink’ phenomenon.[8]

So, in summing up, this paper suggests that Australia actually has a more complex, diverse, sophisticated and porous policy advisory system, than many suggest. Certainly, while the Australian system is not without its flaws, and these will be highlighted later, one of the arguments in this paper is that since the 1970s in many ways the Australian advisory system has become more open and complex than its United Kingdom counterpart. Thus, an important area for further research is to identify more accurately and to classify more clearly the range of advisory policy institutions so as to distinguish them from each other and appreciate their varying roles and impact on the advice they provide. It would also be worthwhile to understand the different types of advice offered by different institutions and to analyse when and why such advice is both sought and accepted. Such issues are beyond the scope of a paper of this type, but remain areas for further research.

What are some issues in the advisory process?

There are a range of issues that we should consider in relation to the advisory process.

One of the emerging issues given the perceived increasing politicisation of the public service, is whether governments receive the full range of views that are available. Do governments seek or receive alternative views? This has been one of the underlying complaints against the Howard Government in Australia, the Bush Administration in the United States, and Blair Government in the United Kingdom in relation to the Iraq War. It has been the basis in Australia, in particular, of complaints by certain former officers serving in Australia’s intelligence services and been subject to various investigations (eg the Flood Inquiry).

Of course, there are other factors at work than just perceived politicisation of the public service. Hierarchy, poor communication processes, departmental politics, and groupthink all contribute to alternative views sometimes being suppressed, ignored or just not heard through the ‘babel’ of advice that percolates up through any bureaucracy.

Nevertheless, many believe that increasing political intervention in senior public service appointment processes, the pressure to give advice that the public service thinks its masters want rather than what they need, is an important underlying cause of these problems.[9] That many departments now see their minister as their primary ‘client’ and the view that the ‘minister always gets what he wants’ are reflections of this trend. In such an environment it is increasingly difficult for alternative view-points to get up through the system. Are there ways of overcoming this problem? Whether governments can afford to have alternative advice sources either within or close to their ears, and if so, how this can be best arranged are real issues that need to be addressed.

Another concern is that governments sometimes seem to be deaf, or they do not really want to listen to advice even if it is tendered. Sometimes this deafness is selective. Governments too often appear to have made up their minds before acting. Advice seems superfluous or if sought at all is only used to bolster particular courses of action. In other cases governments ask: ‘Why weren’t we told?’ after some scandal becomes public. In many cases, governments were told, but for all sorts of reasons deliberately ignored the advice, or did not listen properly to what was being said. This seems to lie at the heart of the issues concerning the oil for food scandal in Australia. It has also been a feature of complaints about corruption as occurred in Queensland during the 1980s under the National Party. Everyone knew, it seems, about police corruption, except the government. During 2005 the then Queensland Health Minister, Gordon Nuttall, stated he was unaware of complaints about overseas doctors—a view he subsequently changed when contradicted by his own departmental deputy director-general in front of a parliamentary estimates committee.

Expertise versus political advice is another emerging issue. Public servants are often told: ‘You don’t understand the politics of this issue’ as a reason for not presenting certain advice to ministers. Well, most public servants generally do understand the politics of the issue, but want their expert ‘fact’ based advice to get into the minister’s office where the political judgements can then be made, but at least based on having the ‘basics’ in place. Too often the desire for ‘political’ advice so dominates the advisory process, made worse by the extensive growth of inexperienced people called ministerial advisors who sometimes interfere and interrupt the flow of accurate information, that ‘expertness’ or content-rich advice gets driven out of the advisory process. There is a place for political advice, but ultimately ‘good’ politics will be driven by ‘good’ policy.[10] Extreme examples of politics driving out rational advice may be seen when scientists are asked to skew findings to suit certain political agendas as occurred in Queensland under National Party governments in relation to environmental issues during the 1980s. More recently, it has been argued that CSIRO scientists have been prevented from making public statements concerning greenhouse issues as it contradicted the Howard Government’s view on global warming.[11]

Suppression of unpalatable information and advice and secrecy in terms of the basis of why governments take certain policy actions are further related issues. This has become more problematical partly because of the increasingly politicised public service that too easily does a government’s bidding. There are numerous antidotes to these issues, although freedom of information laws, given the way they have been misused in Australia, are not always effective. Too often, we have only found out about these problems following special external inquiries, like royal commissions which with their very real powers of investigation have helped clear the clogged information channels, opened up secret files and highlighted how governments suppressed information and advice on particular issues. The 1980 Royal Commission into the Federated Ship Painters’ and Dockers’ Union (Costigan Royal Commission) and the 1987 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody are examples in exposing what government did and did not know and also what they were unwilling to ask. More recently, in 2005, as is discussed below, two royal commissions in Queensland highlighted how complaints about the malpractices of overseas doctors and vital information about public hospitals were deliberately suppressed and distorted by successive health ministers and cabinets.

Content knowledge inside the public sector seems to be suffering in the face of a managerial revolution that has been enacted around Commonwealth and state bureaucracies. Once upon a time we used to have public servants who had real content knowledge in the policy area they worked. These days, with the emphasis on managerial competence and performance, policy content knowledge is often lacking. Exacerbating this problem is that senior public service managers, the Senior Executive Service (SES), are recruited on short-term contracts and have little time to understand the history of policy issues or to take full responsibility for the many changes they often instigate. Once upon a time, senior public servants rose up through the ranks, and had experience about what worked, and what did not work in the field. This is a real problem in the advisory game, and partly explains why governments sometimes seem not to learn from previous mistakes.

Short-termism in thinking about policy issues further undermines effective policy advice. Governments are very focused on one thing: getting re-elected, maximising votes, and doing what they have to do to get over the line at the next election. It is extraordinary how this not just focuses their attention, but monopolises their thinking. It is made worse at the national level (and in Queensland) by the three year term. The average length of most federal governments is about 2.2 years. Few policy initiatives can be developed, implemented and have any real impact in such short timeframes. This also drives governments to demand immediate results and to allocate resources to those areas of public policy most amenable to this sort of pressure, to being able to show ‘measurable’ results. It reduces the willingness of governments to allocate resources to long term strategic thinking—a particular problem about Australian policy making noted by others.[12] This problem is further exacerbated, as noted above, by the short term contracts of the SES.

Another issue is organisational amnesia. It has become a real problem in Australia and other democracies where public sector ‘reform’ has become the goal, rather than the means, for many governments.[13] Because during the last couple of decades the public service in Australia and elsewhere has been constantly restructured, increasingly politicised, and run by managers with limited tenure, the bureaucracy is no longer good at being a bureaucracy. It has lost its organisational memory. There is often a two and a half year turnover in staff and different organisational units. In the Queensland Government a science and technology unit established in 1994 was abolished in 1998, and its personnel dispersed and programs dismantled. The same unit was re-established in 2000. The new appointees had no idea what had gone on before and had to start all over again. The public service had forgotten what had been done previously, and given the increasing high turnover of senior staff we have a situation of ‘stop-go’ policy making and reinventing the wheel.

The national advisory field: Who’s who in the advisory zoo?

While we have already mentioned some of the different advisory bodies earlier let’s identify these more clearly and make some assessments as to their roles and potential areas of reform.

Some key issues in reviewing these different bodies and institutions include:

- What are they?

- How independent are they?

- How do they work?

- What type of advice do they provide?

- How are they perceived?

- Are they effective?

These are the questions that we should be asking about our policy advisory mechanisms. The point is we have multiple mechanisms and multiple processes in place. It is not just a single system and not all policy advisory bodies are created equal.

The following bodies work in the national advisory field in and around government, and are essentially run by governments, or sponsored by governments, or paid by governments. These bodies are set in order of their closeness to government:

- Government departments, and inside departments, there are numerous policy units. Twenty years ago you would not have seen a policy unit in existence. Now, such units are commonplace. The issue with departmental advice, for reasons already outlined, is that it is increasingly driven by political considerations and ministerial intervention. Some departments like Treasury still have a certain degree of perceived independence and prestige, but one suspects that even here there is a decline in their status.

- Ministerial minders, of which there were only a few 30 years ago have grown in number and changed in origin. There are now an estimated 400–500 ministerial staff in Canberra. Most are recruited from outside the public service. While there is a legitimate role for externally appointed ministerial staff as a means to check departmental advice and to provide ‘political input’ (‘hot’ advice, see below) the issue is whether they impede advice from agencies and have the experience to provide the sort of advice needed.

- Consultants, while used previously have now increased dramatically in numbers and costs.[14] They are everywhere, and have varying degrees of openness in their processes and reporting. Some see their use, especially by the Howard Government, as a means of avoiding the more open external public inquiries. Others see consultants as a means of bringing greater expertise into government.

- Advisory bodies attached to government departments that relate to different interest groups or key sectors, such as the AIDS, environmental issues, or manufacturing advisory groups. These are particularly seen at the state level and such bodies are what may be described as ‘representative’ advisory bodies as they try to include in their membership representatives from across a particular policy community. In some cases such advisory groups hold a certain expertise, but they primarily reflect the expertise of interest groups rather than holding ‘independent’ expertise.

- Specialised policy bureaux within government are another category and are found specially at the Commonwealth level. These bureaux are sometimes statutory based, but often are not. They are seen as having a particular expertise in an area of policy and a certain degree of independence. The Office of National Assessments is one example. Others of interest include the Australian Bureau of Agricultural Resource Economics (ABARE). Such bodies have been entitled policy research advisory bodies (PRABs) because they provide policy advice based on research and analysis and not just through the collection of information from interest groups.[15]

- Statutory-based advisory bodies. The aforementioned Tariff Board is an example and it has evolved into the Productivity Commission (previously the Industries Assistance Commission and then Industry Commission). These bodies conduct inquiries, release draft reports and inject considerable amounts of ‘rational’ policy information (although often from certain limited perspectives) and some degree of independent analysis into the public arena.

There is considerable waxing and waning of these different advisory bodies as governments come to power with new interests and as problems and issues emerge. Some get reviewed and are abolished (eg Australian Institute of Multicultural Affairs was abolished in 1986, but was replaced by the Bureau of Immigration Research a couple of years later, which has since been abolished). Others are modified, amalgamated, or given renewed missions.[16] The Australian Institute of Criminology, for instance, was reviewed during the 1980s and given a renewed mandate. It is presently being reviewed again.

- Intergovernmental bodies, ministerial councils, and the Council of Australian Governments are key advisory agencies focusing on federal-state related policy issues. There were over 90 of these at one stage. However, given the centralisation tendencies of the present Howard Government and its adoption of what may best be described as ‘feral federalism’ then the real policy roles of these bodies needs considerable reassessment.

- Parliamentary committees have since 1970 at the Commonwealth level in particular become more prolific in number, wider-ranging in scope and thanks to the Senate, more probing in their investigations.[17] To some extent, they have taken on some of the roles of public inquiries. However, parliamentary committees have several flaws. For instance, they are composed of elected officials and thus often become arenas for partisan battles. Such partisan membership also means that they lack the same sense of independence or expertness as other advisory bodies. Their inquiries are often controlled by executive government, as are their resources. Rarely will a parliamentary committee inquiry satisfy those wanting expert or independent policy advice.

- Public inquiries, as noted, are temporary, ad hoc bodies appointed by executive governments with the majority of their members drawn from outside of government. They are not chaired by current politicians. They can be royal commissions, task forces, working groups, commissions, and committees of inquiry. At the national level there have been over 120 royal commissions since federation, and some 500 less formal public inquiries. With the Whitlam Government there was resurgence in public inquiry use, including royal commissions—a resurgence that has been maintained until the Howard Government. Although public inquiries are temporary bodies, the suggestion is that public inquiries have been used to provide advice on some of Australia’s most important policy changes (eg pensions, public service, financial deregulation, national competition policy, television) as well as to investigate areas of corruption, and as such constitute an ongoing and important part of the policy advisory institutional framework in Australia.[18]

In addition, there are other policy advisory bodies that are external to government, though some are funded in whole or part by government. These include:

- Research advisory bodies attached to universities, usually funded by government or supported by consulting activities;

- Party political research bodies or those closely attached to particular parties such as the Menzies Research Centre based at federal Liberal Party offices in Canberra;

- Interest groups are increasingly sophisticated in their research techniques and capacities. The National Farmers Federation, for instance, employs a large research team;

- Lobbyists have varying research capacities;

- Think-tanks, a particular United States phenomenon,[19] do exist in Australia, but although there are numerous bodies with this title there are relatively few in number that are privately funded. Examples include the Centre for Independent Studies, The Sydney Institute, and the long established Institute of Public Affairs in Melbourne. Although some think-tanks are rumoured to have secret ‘ins’ with government and produce reports such roles are more often than not exaggerated and their research capabilities often limited.

Figure 1 outlines, from left to right, the relationship between decreasing government control and increasing perception of independence in advisory bodies. Starting on the left, ministerial advisors owe their livelihoods to ministers. Therefore they will do what they are told. Department policy units, project teams, consultants—they owe their allegiance to the department. They will do as they are told. Interdepartmental committees are set up by executive government and operate within departmental structures and are rarely public. Advisory committees are attached to departments and their members are appointed by executive government. Research bureaux are a bit more independent because they often produce public reports and they can get some criticism. Parliamentary committees are even more independent, because they are in the public arena, their processes are public, but as noted they are made up of partisan members who often fight out the partisan game. Permanent advisory bodies like the Productivity Commission and special think-tanks are much more independent. Public inquiries are the most distant from executive government though appointed by them. This is because their membership is drawn from outside government and their processes are highly public limiting overt government interference in their investigations and deliberations.

Figure 1

Executive government control of advisory bodies

The state advisory scene

While the state advisory environment largely follows the national scene there are important differences.

For instance, there are fewer advisory bodies overall, and they are on a lesser scale than their national counterparts. There are few external advisory bodies to government. There are not many independent statutory advisory bodies, as distinct from regulatory bodies. There are no bodies like the Productivity Commission investigating assistance to business or reviewing micro-economic reform issues. Assistance to business remains very much an executive government prerogative kept secret under the ‘commercial in confidence’ umbrella.

There are fewer parliamentary committees at the state level and they appear far more under executive government control than their Commonwealth counterparts. Upper houses have exerted some influence from time to time and it will be interesting to see the impact of the changes made to the Victorian upper house after the 2006 state election.

State governments also tend to resort to public inquiries less frequently and on a narrower range of topics than at the national level. State royal commissions have in recent years only been appointed in emergency crisis situations like the hospital crisis in Queensland, or corruption and maladministration scandals with the banks in Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia during the 1980s or in relation to police corruption (Queensland, New South Wales, Western Australia).

Interest groups do have a state organisational base, but these have limited research capacities and are more focused in responding to member needs and direct lobbying than ongoing policy research and debate. Indeed, excessive criticism of a government can result in certain peak industry associations being locked out of the consultation process by the offended state government as occurred with Commerce Queensland following the 2003 state election.

External think-tanks rarely have a state focus. The Brisbane Institute is one example of this, but its impact has been limited, partly because it relies on support from the state government or those with state government links and its criticisms of some policy areas have not been appreciated inside government.

Oliver’s assessment about the closed and non-porous nature of the policy advisory system in Australia is much more appropriate if applied to the state government scene. However, even here, some careful concessions need to be made as to its veracity.

Some recent trends in providing advice to government

In addition to the different advisory bodies identified above a number of other trends can be observed in relation to advisory mechanisms in Australia.

First, one of the trends inside government is increasing centralisation at a departmental level. One of the great developments in the Australian public sector in the last decade has been the rise and rise of the Prime Minister’s Department[20] and its state counterparts, the various premiers’ departments.

These new central agencies have come to rival the traditional ones like Treasury. If the range of functions of premiers and prime ministers’ departments are analysed it seems they incorporate the whole range of government functions reflecting their whole of government monitoring role and the increasing policy and political importance of the prime minister and premier.

These departments of premiers and prime minister are often the incubators for new policy areas and units (eg women’s units, multicultural affairs) or provide accommodation for serious problem areas (eg indigenous affairs) where there may be concerns about the competency of line agencies (and their ministers) to tackle the issues appropriately. There is a sense that premiers’ departments want to control everything. In Australia, and to a lesser extent the United Kingdom, premiers’ and prime ministers’ departments have really become the prime policy co-ordinator in both providing advice and in overseeing the implementation of executive decisions. Despite all those management words like strategies, whole of government collaboration, partnerships and so on, premiers’ and prime ministers’ departments are really about exercising control on behalf of the chief executive officer.

Second, there has been, as noted, the ongoing increase in the number of ministerial minders. Their numbers at the Commonwealth level have quadrupled during the last two decades.[21] While there is an argument that ministerial minders can provide the strategic advice needed to drive policy initiatives through over-cautious departments concerned more with maintaining and implementing policy, there has not been enough attention as to the problems minders cause.

In relation to minders there are three issues:

1. Many minders are young inexperienced people who think that doing policy is writing a comment on a briefing paper from a department. They often do not understand the background to issues or have any experience in the ground implementation of policy.

2. Ministerial minders are activity-driven people and this, plus the need to justify their position, means that they will tend to criticise, knock, expose minor problems in public service advice and to treat such advice with some suspicion, as if the public service is trying to get something over the minister. This creates a very difficult relationship between ministers and the public service.

3. There is the issue of accountability. Ministerial minders increasingly act as de facto ministers, giving instructions not just to senior public servants, but to those down the line. This has raised some concerns of late and provoked suggestions[22] to set some parameters for the interactions between ministerial minders and the public bureaucracy. The problem is that minders are not able to be held to account under present arrangements.

In relation to policy research advisory bodies like policy bureaux inside departments and statutory based advisory agencies, one important trend under the Howard Government has been for these bodies to be consolidated and reduced in numbers. They still exist, but they are not as numerous as they once were. The Howard Government seems less interested in seeking alternative, independent sources of advice the longer it is in power.[23]

The growth of consultancies needs further assessment. Consultancies offer governments several advantages: (a) they can be expert and (b) they do not have to be public. So you can get an outside expert person in but you do not have to make the process public. One of the reasons there has been a slight decline in the external, open and more independent public inquiries under the Howard Government is because it has sought to use consultants more often. The Howard Government is not alone in this practice.

Related to consultancies is the increasing outsourcing of policy advice to bodies outside of government. Whether this is resulting in a loss of expertise or a hollowing out of executive government remains to be seen, but it is certainly an area worthy of further monitoring.[24]

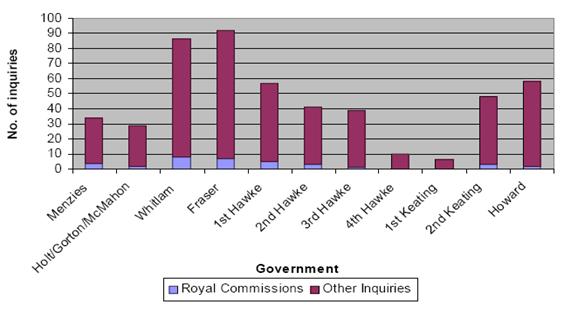

Public inquiries in Australia, royal commissions and other bodies identified above, declined for a long time in numbers from the post-World War II period, right through to 2nd December 1972, when with the election of the Whitlam Government public inquiries increased in numbers dramatically. Figure 2 compares the number of public inquiries under governments between 1949 and 2003.

The Howard Government, and its current state counterparts, have been less enthusiastic in appointing public inquiries in general and royal commissions in particular. Since 1996 the Howard Government has only appointed four royal commissions. Other governments have also followed this practice. The Bracks Government has resisted appointing a royal commission into the police, while in Queensland the two royal commissions established by the Beattie Government into the overseas doctor issue only occurred when all other options had been tried.[25] John Howard, like the current state Labor premiers, has learned that appointing inquiries can be a tricky business. Nevertheless, public inquiries in Australia have become, and remain, a quite important advisory mechanism. They are appointed both for legitimate policy reasons of getting information, trying to sort out what to do, and for what may be called politically expedient reasons of showing concern, raising the flag, and agenda management. Certainly, the evidence is that the public inquiry mechanism has been invoked much more in Australia in recent years than say in Canada, the United Kingdom or New Zealand.[26] It is worth considering why this is so. One explanation is that with the erosion of independence of the public service, increasing political intervention in appointment processes and even questionable independence of universities, public inquiries and especially royal commissions have become the ‘institution of last resort’ for governments concerned about ensuring there is a legitimate and independent process of investigation underway.

Figure 2

Number of Royal Commissions and other public inquiries per government 1949–2003

Problems with advisory mechanisms

Let’s now review some of the tensions in providing advice to government. Some of these have been discussed, but in a couple of cases they need further elaboration.

One tension is between government departments and external advisory bodies. Government departments do not really like external advisory bodies, whether permanent or temporary. Take the environment area, where we have bodies like the Wet Tropics Authority and the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA) in North Queensland. These bodies are not just regulators, they are also advisory bodies and they offer alternative viewpoints to those of departments, have their own expertise and rationale, are given their own budgets, and have some freedom to pursue their own lines of research. There is thus a tension between the Environment Department and these bodies, because there is an issue of control, alternative sources of advice and competing expertise. In recent times, the tendency in this policy area has been for departments to seek to incorporate these bodies back into their particular administrative orbit. Hence, the Wet Tropics Authority, following a review, is a shadow of its former self in terms of independence, staffing and powers. A review of the GBRMPA released in 2006 is expected to produce similar results.

Another tension is between competing expert views. Figure 3 gives an example of competing expert views on the issue of unemployment. A lot of different views are given about what causes unemployment. Unemployment can be viewed as an education issue, a result of too generous unemployment benefits, an industry adjustment problem; some think it relates to the way we look at participation rate, and values and attitudes towards work; and some economists think wages are too high, and some look at it as a demand function. We have to get expert knowledge, but there is different competing expert knowledge out there, and this is often very difficult for governments to resolve.

Figure 3

An example of competing expert advice

Based on A. Harding, ‘Unemployment policy: a case study of agenda management’, Australian Journal of Public Administration, Vol. XLIV, No. 3, September 1985, pp. 224–246.

One of the tensions that is not fully appreciated is what has been described as ‘hot’ advice versus ‘cold’ advice. Figure 4 compares the characteristics of what I call ‘hot’ and ‘cold’ advice. Bureaucrats and academic experts believe their role is to give cold, rational advice. They are not ignorant of the political context, but see their role to give the advice that is factually based and long term in focus. Hot advice is what drives ministers and their minders. It is meant to be an overlay to rational advice, and serves a very legitimate role in a democracy. After all, democratic policy-making is not just about implementing formula based policy solutions, but about accommodating interests, building support and developing policies that are acceptable and able to be implemented. However, the problem is that ‘hot’ advice seems to be coming more dominant and the public service is increasingly expected to move more and more into the hot side of the advisory game—to think about the political consequences rather than to focus on developing rational policy proposals. We have this sort of disjunction because the public service, especially at the SES level, is increasingly politicised or at least has a more tenuous hold on its position than previously. In such circumstances, it is often very hard to provide cold, rational, and independent advice.[27]

Figure 4

Hot and cold advice

Source: S. Prasser, Royal Commissions and Public Inquiries in Australia, Sydney, Lexis Nexis, 2006.

Another tension has been that bodies like that of the auditors-general that are supposed to provide independent reviews of government have been under attack by executive government, especially at a state level. It is a real problem in Victoria and New South Wales. In Queensland recently, when the Auditor-General was to review government spending on advertisements he was summoned to the Premier’s office and on the same day it was announced that the Department of the Premier and Cabinet would be reviewing the Auditor-General’s office. Now that seems to be having a loaded gun at the Auditor-General’s office. After all, the Auditor-General is supposed to be an officer of parliament, not an officer of the executive. These are exactly the problems that the Fitzgerald Inquiry highlighted in 1989 about Queensland government. They are important issues we should consider when assessing the policy advisory process.

As more and more advisory processes come under executive government influence and control, the public questions the legitimacy of the advice that governments choose to use and to justify its decisions. In Queensland when the Department of Premier and Cabinet several years ago produced a report about public hospital waiting lists and availability of doctors, the Australian Medical Association (AMA) was sceptical about the validity of the analysis. Because of the way our public sector has been politicised, we no longer believe its assessments. We now have a crisis in legitimacy in the policy advisory game. Who do we believe when they say the best advice given to us was by the department, or by another body? Do we really believe it is independent advice? This is one of the great challenges facing our democracy. In the case of the Queensland health issue, the subsequent royal commission in 2005 confirmed the AMA’s concerns.

Given these trends, then one of the last key independent advisory mechanisms that has too often been forgotten is public inquiries such as royal commissions. Why do they get appointed? They are, as noted, ‘institutions of last resort.’ When something is really rotten in the state of Denmark, we can at least hope we might get a bit of truth from these sorts of bodies. They are perceived to be independent; they usually have a rational process; they use open public processes and report publicly. The public service is too overloaded and politicised to do this sort of work. Other advisory mechanisms are also compromised, but public inquiries are seen to be impartial, independent and they are often made up of people who are considered to be authoritative, and expert in the policy problem, and they are composed of members whose futures do not lie with ongoing government employment.

Royal commissions in particular are the ‘Rolls Royces’ of inquiries, because they have real power: they can make people appear as witnesses, they can make people give evidence, and they can enforce the collection of information. Royal commissions are the last bastion of independent advice, and because of their public processes, we can see them in action. We can see the squirming of witnesses in their seats; we can see the evidence being collected, and inevitable contradictions and inconsistencies. In Queensland during the recent second royal commission into the overseas doctors’ scandal (Royal Commission into Queensland Health—the Davies Royal Commission) we could see the former ministers for health trying to explain how they covered up waiting lists, suppressed information and misused the cabinet process to avoid freedom of information laws. We finally found that there is not just one waiting list in Queensland, but several waiting lists.

Why rational advice goes astray

While those of us in the public service and the numerous advisory bodies and even elected officials themselves want to give and receive rational policy advice based on sound analysis, clear options, some form of checking of resources, and cost benefit analysis, government and policy advisors alike are constantly being knocked off course by other influences and players. Some of these pressures as outlined in Figure 5 below include:

- Ideology and beliefs: While important, ideologies are highly value-based and not always developed as a result of clear analysis. New governments are particularly influenced by these traits and often try to retain their ideological purity even when circumstances indicate the inappropriateness of policy based on such frameworks. Interestingly, the present Labor Opposition’s prime criticism of the Howard Government’s industrial relations changes is that they are anchored too strongly on ideological rather analytical perspectives;

- Party politics: Sometimes rational policies cannot be pursued because party politics, history and platforms are totally opposed to these proposals. This has become less of a problem as parties have become less ideological. The Labor Party too has become less bound by the party platform. However, what is not always understood is that governments often choose policies based less on rational analysis and more on market expectations (surveys and opinion polls) and on what their opponents are or may be proposing;

- Departmental politics: We know that government and the public bureaucracy is not a single monolithic structure, but consists of competing agencies chasing bigger shares of the budget and greater control over different policy areas. This public choice view[28] may be open to criticism, but anyone who has worked in the bureaucracy appreciates that government policies are easier to develop than to implement and that what is sometimes the ‘right’ policy is impossible to implement because of departmental rivalries and competing agency perspectives of particular policy issues;

- Organisational factors or ‘group-think’: As highlighted, a major impediment to rational policy advice in any organisation is preventing alternative viewpoints to be expressed. Organisational factors such as hierarchy and groupthink stifle innovative thinking. There needs to be a means for alternative viewpoints to be expressed without people being skewed in the process;

- Irrational and illogical thinking, lack of facts: So many government decisions are based on hints and ideas, rather than sound analysis. Governments, as observed in relation to many large ‘prestige’ projects fail to test if there is a real demand for such monuments (the ‘build it and they will come’ syndrome) and even when a project is clearly over-budget and failing to meet its most basic requirements, governments continue to pour funds into these projects because of previous investments which they are unwilling to write off (the ‘sunk costs’ approach);[29]

- Economic factors: Of course, all policy advice has to be tempered by an appreciation of economic and budget realities. There is never enough money to implement policies as fully as intended. Compromises have to be made and budget limitations acknowledged. Sometimes, such exigencies doom policies to failure.

Figure 5

Why rational advice goes astray

Queensland Health: a closed system?

Examination of the recent Queensland overseas doctors’ crisis highlights some of these different issues.

The background to the Queensland hospital crisis was that complaints from professional bodies, individual medical staff and some patients, about the competence and qualifications of overseas doctors eventually became a public scandal. The issue was intricately entwined with other health issues such as public hospital surgery waiting lists, hospital funding, specialists’ wage levels, the adequacy of medical training and recruitment and Queensland’s over-reliance on overseas doctors. Eventually, the Beattie Government appointed a royal commission to investigate the allegations. While the initial royal commission was later disbanded following Supreme Court findings of the perceived bias of its chair, a new royal commission, the Davies Royal Commission, was quickly appointed.

The Davies Royal Commission discovered a number of issues pertinent to our focus on advisory processes. Complaints about medical malpractice were suppressed by senior health department staff. Information about hospital performances and the state of the Queensland health system was not released or deliberately misleading. Information and briefings up the Health Department’s hierarchy was often distorted or did not go above certain levels. Ministerial press statements, departmental annual reports, and answers to questions in parliament were inaccurate. The Health Department suffered from too many reorganisations, overcentralisation and inadequate funding. Senior Health Department officials lacked content knowledge and there were suggestions that there had been political interference in appointment processes. Alternative viewpoints and criticisms were not tolerated. There was a lack of independent external review processes. Both ministers and cabinets were condemned for deliberately seeking to misuse freedom of information exemption to suppress information on vital issues like hospital waiting lists and acting contrary to the public interest. Indeed, the Davies Royal Commission exposed that there were not one, but two hospital waiting lists and explained how governments manipulated these to promote false public perceptions of public hospital performances.

Conclusions: suggestions for better advisory processes

It is no use complaining unless you have some solutions.

First, it seems clearly established that the Australian policy advisory system is more complex and porous than contended by Oliver. The Australian policy advisory system is also reasonably diverse—not as much as in the United States, but scale, resources and complexity are really on a different level. There are, in the Australian system, numerous entry points for interest groups and there are numerous public and semi-public platforms for advocacy. Our public inquiries and some of our statutory-based advisory bodies like the Productivity Commission are really very good at providing opportunities for genuine input.

Of course, unlike the Swedish commission inquiry and policy development process, Australia’s policy processes appear ad hoc. For instance, it is up to executive governments to decide when to appoint a public inquiry or not. So there’s no certainty about that. In Sweden a public inquiry is appointed before any major action occurs. These inquiries are not dominated by government or even parliament but are an independent process.

This does not mean that all is well. The Queensland hospital crisis illustrates just how policy and advisory processes can deteriorate. There is a tendency in recent years at the national level for executive government to seek greater control on both internal advisory processes, to reduce independent sources of advice, and to rely more on internal sources of advice, but not necessarily on the department, but rather on the ministerial office with its increased number of ministerial staff. It is the ministerial office that has become an increasingly important driver of policy advice. Also, governments continue to act secretly.

How can we ensure there is better policy advice going to governments? Is such a goal a lost cause?

Ideally, we have to get better separation/insulation between elected officials and departments. They have become too close. Ministers now appoint department heads. At state level, political interference has gone down further and further into the lower levels of bureaucracy. We are filling positions with ‘yes’ people all the time. So there has to be some insulation.

Also, we need greater transparency in what is being asked for from the public service and what is being provided. We need to know more accurately just how the economy, health, the environment and industry sectors are really performing. Some real performance reports in the annual reporting process might allow better assessment of advice and information about what governments do.

Ministerial minders have become a problem and ought to be reigned in both in relation to their numbers, roles, and accountability arrangements. Minders are often supposed to be ‘second guessing’ the public service advice. Too often they seem to be just guessing. They often do not know what they are talking about; they cannot have the experience of people in the field who have to deliver policies and know the realities of doing policy as distinct from just thinking about policy in an abstract way.

Next, we need to depoliticise the public service. How do we do that? We have done away around Australia with that unique Australian development, the public service board. Public service boards were established in Australia following royal commissions into political corruption of the public service.[30] Public service boards were a great Australian innovation and unfortunately in the drive to ‘managerialism,’ we abolished them around Australia. Their successors, the different public service commissions, have different roles. So there needs to be some sort of independent body to insulate the public service from political interference, and to oversee appointments and promotions.

In addition, we need to re-examine the appointment processes of senior public servants, department heads, judges, and heads of statutory bodies. Such positions have become partisan prizes. The American Senate confirmation process might be one alternative so as to ensure governments appoint people who are competent and not just the party faithful, and to restore some bipartisan ownership of such appointees. More recently, others have proposed that Australia should adopt recent models from the United Kingdom in relation to more independent processes in the appointment of judges.

Then of course there is the need to initiate parliamentary reform, especially in revitalising upper houses around state parliaments. All knowledge does not reside in executive government and it is good for governments to have to do deals and argue their case and get proposals through parliament as successive Commonwealth governments have had to do with the Senate for some time. In Queensland we do not have an upper house and it shows in the lack of accountability and the executive dominance of all decision making. Even though the Howard Government now has the numbers in the Senate, the very nature of Coalition politics and its thin majority means the Howard Government cannot take the Senate for granted. The Howard Government still has to negotiate to get its significant legislation through the Senate.

Certainly reforming parliament and establishing effective upper houses rather than creating extra-parliamentary institutions like anti-corruption bodies can improve the accountability game and the openness of the policy development process. We have a Crime and Misconduct Commission in Queensland that does great work, but they can also be under pressure from the government from time to time.

Last, we have to restore content knowledge over managerial competencies in the senior ranks of the public service. This will lead to a much better advisory process. Experience and knowledge about the subject matter surely must count. Unfortunately, as a society we often do not always give due weight to experience and content knowledge. Good process, although important, alone will not drive effective policy advice.

The Australian policy advisory process has many positives. Some major policy problems have been effectively managed during the last decade, but certain trends identified in this paper need to be reversed if we are going to improve the quality of government and the quality of decision-making in this country.

Question — I don’t think that the problem with the ministerial advisors is that they are necessarily ignorant young Turks, because if you look at the Prime Minister’s office you have some extremely experienced people in there, including a number of former public servants and a number of other public servants who are effectively on secondment and will go back into the bureaucracy at very high levels. The question seems to me the issue of accountability of those people, or the lack of accountability. Would you like to comment on that?

Scott Prasser — Well, I think that is one of the gaps that has developed. The fact that ministerial minders don’t have to appear before committees of Parliament seems to be an issue. It’s true what you say about the Prime Minister’s office. I was referring to ministerial minders very broadly. I think that the whole ministerial minder process, which has grown topsy-turvy in the last 20 years, needs to be reviewed. Secondments from government departments to ministers’ offices have long been the case, but it’s the bringing in of people from outside the system. The sort of people I am talking about are often chasing political seats and go on to become members of Parliament themselves. I have no problem with secondments from departments and so on. But the ministerial minder system needs to be reviewed and I think some of the great leaders in Australia understood that there should be some limitations on just how many ministerial minders should be in vogue.

When I worked in Canberra, ministerial staff was five. One officer was seconded from a government department, and three administrative people and myself were brought in from outside. Today it’s much bigger than that. One of the problems with ministerial minders is that many things are said and done in the name of the minister without necessarily correct authority. On the issue of accountability, when we got a note from a ministerial minder about doing something, we had to ask ourselves should we do it, or should it go back through the system. There was a bit of a view that we should just do what the ministerial minder said. But if things went wrong, who would cop the flack about that instruction? There are some issues there about the merging between ministerial minders and the bureaucracy, which I think need to be resolved.

Question — I’d like to ask a question about how you get away from the contract system in the senior public service. There are some very high salaries paid for those people on contract and they are managing upwards the whole time. As soon as they give advice that the minister or whoever immediately above them doesn’t want, their contracts are in jeopardy, and this goes down to perhaps the third or fourth level in departments.

Scott Prasser — Good question. I’m going to write a book one day and it’s going to be called jumping. Once upon a time ministers jumped up and down because they had to face elections and they used to get in a sweat about that. Then we started appointing and putting on contract department heads. They started jumping up and down—they wanted to get brownie points and meet their performance targets and KPIs and that sort of thing. Then we started appointing executive directors on contracts, the next level down, and they started jumping, and then further on. Everyone was chasing the short-term gain all the time and they worried about their performance and their KPIs, and the trouble is this was very short-term focused. My experience with what we have now is that people on contracts are often afraid to tell the minister the truth about what’s going on. In Queensland the department heads report to the Premier, not to their minister. What department head is going to tell the Premier really bad news about certain things, when their performance contracts, their extra pay, are all decided on this sort of basis? I think this is a crazy system we’ve got ourselves into. Now I know the old system of seniority certainly had its problems, but I think this present system needs to be totally examined.

Question — I’m wondering if you think that the Freedom of Information Act is in any way having negative impacts on public servants being prepared to offer frank and fearless advice. How do you think it might be changed to get the balance right and encourage public servants to offer more frank and fearless advice?

Scott Prasser — You think because of FOI public servants won’t offer frank and fearless advice?

Question — In the short term FOI was one step forward, but I think in the medium to long term, it has been two steps back. Because FOI has made advice more transparent, people have developed more and more mechanisms to get around it and it is perhaps now having a negative impact. Public servants know that if they do offer that frank and fearless advice, or a variety of expert opinion, that will then come out. They might have several people say one thing and one person say the other, and then opposition parties will use that to attack the government. So the government doesn’t really want to get that variety of expert opinion and public servants are adjusting to that new reality, and I believe a lot of the mechanisms you are talking about are working to circumvent the transparency of the system and I wonder if that is leading to a good outcome. They talk about the doctrine of unintended consequences—something looks good in theory, but when put into practice, it has the opposite effect.

Scott Prasser — America’s FOI has been in operation for a long time and I think it has been a good thing. My view is that we should have departments and ministers separated more. I think that when ministers request information, it should be very clear what they are requesting and the information should be transparent. I think we should put the onus back on the politicians. What I liked about the old National Party government in Queensland—I know that’s not a popular thing to say—is that they didn’t pretend to dress their decisions up as totally rational decision-making. They didn’t pretend that they were doing it for the public good. They said they were doing it for votes. When Russ Hinze was asked: ‘Mr Hinze, are you moving the road to the Gold Coast near your hotel that you own, and aren’t you also the Licensing Minister as well?’, he replied: ‘Of course I am, and what sort of minister do you think I am?’

When David Hamill, the Labor Party Minister for Transport was talking about roads to the Gold Coast, we went through this charade of reports and consultations and so on, but we knew the game that was being played. I think the onus has to be put back on the politicians. We provide the advice, and it is up to the politicians to input their political process. Bodies like the Productivity Commission and the Industry Assistance Commission get their terms of reference, they do the investigation, they give the report, and if the government wants to reject the report on ageing, or ship-building or whatever it may be, they can do it. I think too much advice is tailored to what public servants think ministers want, rather than tailored to what they need. I don’t think FOI is a problem. I think the way it has been manipulated by some governments is the problem.

* This paper is based on a lecture presented in the Senate Occasional Lecture Series at Parliament House, Canberra, on 24 February 2006.

[1] Sue Oliver, ‘Lobby groups, think tanks, the universities and media.’ Canberra Bulletin of Public Administration No. 37, December 1993, p. 134.

[2] H.C. Coombs, Trial Balance. Melbourne, Sun Papermac, 1981, p. 263.

[3] Royal Commission into Australian Government Administration, Report. Canberra, Australian Government Publishing Service, 1976.

[4] P. Weller et al. (eds), The Hollow Crown: Countervailing Trends in Core Executives. London, Macmillan, 1997.

[5] See B. Woodward, State of Denial: Bush at War, Part III. New York, Simon and Schuster, 2006; and R. Suskind, The One Percent Doctrine: Deep Inside America’s Pursuit of its Enemies Since 9/11. New York, Simon and Schuster, 2006.

[6] H. Orlans, ‘The political uses of social research’, Annals of American Academy of Politics and Social Research, Vol. 394, March 1971, pp. 28–35.

[7] A. Downs, Inside Bureaucracy. Boston, Little Brown, 1967.

[8] P. Hart, Groupthink in Government: a Study of Small Groups and Policy Failure. Baltimore, John Hopkins University, 1990.

[9] J. Johnston, ‘Serving the public interest: the future of independent advice.’ Canberra Bulletin of Public Administration, No. 91, March 1999, pp. 9–18.

[10] Scott Prasser, ‘Aligning ‘Good’ Policy with ‘Good’ Politics’, in H.K. Colebatch (ed.), Beyond the Policy Cycle: the Policy Process in Australia. Sydney, Allen and Unwin, 2006, pp. 266–292.

[11] ‘The Greenhouse Mafia,’ ABC Four Corners Program, 13 February 2006.

[12] Ian Marsh and D. Yencken, Into the Future: the Neglect of the Long Term in Australian Politics. Melbourne, Australian Collaboration and Black Ink, 2004.

[13] C. Pollitt, ‘Institutional amnesia: a paradox of the “Information Age?” ’Prometheus, Vol. 18, No. 1, 2000, pp. 5–16.

[14] J. Martin, Reorienting a Nation: Consultants and Australian Public Policy. Aldershot, England, Gower, 1998.

[15] Scott Prasser and S. Paton, ‘Advising Government,’ in J. Stewart (ed.), From Hawke to Keating: Australian Commonwealth Administration. Canberra, Centre for Research in Public Sector Management and the Royal Institute of Public Administration Australia, 1995, pp. 105–149.

[16] Ibid.

[17] H. Evans, ‘The Case for Bicameralism,’ paper presented to the Improving Accountability in Queensland: The Upper House Solution? National conference organised by the Faculty of Law at the University of Queensland and Faculty of Business of the University of Sunshine Coast, Brisbane, 21 April 2006.

[18] D.H. Borchardt, Commissions of Inquiry in Australia. Bundoora, Vic., La Trobe University Press, 1991; Scott Prasser, Royal Commissions and Public Inquiries in Australia, Sydney, LexisNexis, 2006.

[19] Y. Dror, ‘Think Tanks: A New Invention in Government,’ in C.H. Weiss and A.H. Barton, (eds), Making Bureaucracy Work. Beverly Hills, California, Sage Publications, 1980, pp. 139–152.

[20] Patrick Weller, ‘Do prime ministers’ departments really create problems?’ Public Administration (London), Vol. 61, Spring 1983, pp. 59–78.

[21] M. Maley, ‘Too many or too few? The increase in federal ministerial advisers, 1972–1999’, Australian Journal of Public Administration, Vol. 59, No. 4, December 2000, pp. 48–53.

[22] Australian Public Service Commission, Supporting Ministers, Upholding the Value. Canberra, 2006.

[23] G. Barker, ‘Yes Minister’, Australian Financial Review 10 October 2000.

[24] F. Argy, ‘Arm’s Length Policy-making: The Privatisation of Economic Policy’ in M. Keating,

J. Wanna, and P. Weller, (eds), Institutions on the Edge? Capacity for Governance. Sydney, Allen and Unwin, 2000, pp. 99–125.

[25] Scott Prasser, ‘Royal commissions in Australia: when should governments appoint them?’ Australian Journal of Public Administration, Vol. 65, No. 3, September 2006, pp. 28–47.

[26] N. D’Ombrain, ‘Public inquiries in Canada’, Canadian Public Administration, Vol. 40, No. 1, Spring 1997, pp. 86–107; G. Lindell, Tribunals of Inquiry and Royal Commissions. Sydney, Federation Press, 2002; B. Easton, ‘Royal Commissions as Policy Creators: The New Zealand Experience’, in P. Weller (ed.), Royal Commissions and the Making of Public Policy. Melbourne, Macmillan, 1994, pp. 230–243.

[27] See Johnson 1999, op. cit.

[28] W.A. Niskanen, Bureaucracy and Representative Government. Chicago, Ill., Aldine-Atherton, 1971.

[29] See B. Flyvbjerg, N. Bruzelius and W. Rothengatter, Megaprojects and Risk: An Anatomy of Ambition. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2003.

[30] H. Zafarullah, ‘Public Service Inquiries and Administrative Reform in Australia, 1895–1905’, PhD Thesis, Department of Government, University of Sydney, 1986.

Prev | Contents | Next

Back to top