Papers on Parliament No. 47

July 2007

Prev | Contents | Next

It has always seemed to me that the writers of the American Constitution are remembered and honoured to a much greater extent than we honour their Australian counterparts.

There are of course some Canberra suburbs and a few House of Representatives electorates that bear the names of our constitutional founders, but most of them are largely forgotten. The Senate is to be commended for including in its occasional lecture series some of the people involved in our Federation story, as in the last three years we have had Stuart McIntyre on Alfred Deakin and Ninian Stephen on John Quick, and last year we had Leslie Zines talking about Robert Garran. As someone who has written on Australian Federation, I was delighted to be able to attend those three lectures, and today I am pleased to be able to add to what is obviously going to become an annual event: the Senate’s yearly acknowledgement of our Federation story.

In this lecture on Sir Edward Braddon I will be trying to do four things. I will give you a glimpse of his life before he came to Australia (and it was an extensive career); give a brief description of his political career in Tasmania; place him in the Federation story, which of course will be the main task of the lecture; and throughout, hopefully, I will give you some sense of what Braddon was like as an individual.

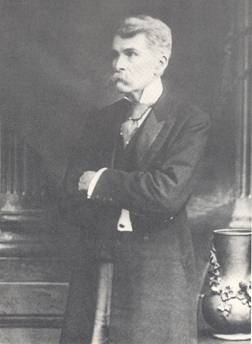

This is a photograph given to me 30 years ago by a very elderly member of Braddon’s English family. The date is uncertain, but Braddon’s appearance matches the description of him given by Alfred Deakin at the time of the 1897–98 Convention:

This is a photograph given to me 30 years ago by a very elderly member of Braddon’s English family. The date is uncertain, but Braddon’s appearance matches the description of him given by Alfred Deakin at the time of the 1897–98 Convention:

An iron-grey lock fell artistically forward on his forehead, bright grey eyes gleamed from under rather bushy eyebrows, a straight nose leading to a heavy moustache and a Vandyke beard. If his locks had been longer his whole appearance would have admirably suited a Cavalier costume.[1]

This is a man who came to Australia in middle age to live on the North-West Coast of Tasmania, but this was after 30 years spent in India, where the story begins.

Edward Nicholas Coventry Braddon was born in Cornwall in 1829. Eighteen years later he travelled to India to work in a Calcutta merchant firm that was run by a cousin. He tells us that he found the work hard to bear; imprisoned, as he put it, behind a counting desk. To his great relief, in the early 1850s Braddon was able to flee the city when he was offered the job of managing a number of indigo factories near Krishnagar. He did this for about five years, and his life was rather more exciting than this might suggest. In July 1855 he was involved in skirmishes which were the result of the uprising of the Santal people in the Bhagulpur district of West Bengal. Two years later, during the Indian Mutiny, he saw armed service in Purnea after enlisting in a volunteer force led by George Yule, later Sir George Yule, President of the Indian National Congress.

Braddon described these martial occasions as ‘a splendid substitute for the tiger-shooting which came not to my hand.’[2] This rather flippant comment is a reminder that hunting, often called ‘shikar’, was an important part of his and many other Anglo-Indian lives in the nineteenth century. In fact the title of his Indian memoirs, published in 1895, was Thirty Years of Shikar. Although he tells us quite a bit about his work, a great deal of the book is devoted to stories of him hunting tigers, snipe and many other animals.

After the Mutiny, Braddon’s life changed remarkably. The Santal insurrection had played a part in the creation in 1857 of a new province, the Santal Parganas. George Yule was appointed to head the administration, and it seems that he was responsible for Braddon’s joining the Indian Civil Service as Assistant Commissioner in the division of Deoghar.

For a man such as Braddon, work as an Indian district officer was ideal. If one was a district officer at that time, much of the work was spent in the field. About six months of the year, in fact, were spent travelling around his district, and it was activity he relished. It was also a job that required a high degree of administrative skill, which he soon displayed, but most importantly, as he tells us in his memoirs, to a large degree he was on his own, relatively free from oversight and interference from his superiors. This gave him the opportunity to develop his own ideas on governmental matters and to put many of them into practice.

Braddon’s work in the Santal Parganas was highly enough regarded to see him promoted five years later to the position of Superintendent Excise and Stamps in the recently-annexed province of Oudh. Today that is part of the state of Uttar Pradesh. He held the position in Oudh for 14 years. During that time Braddon gained further administrative skills and experience, for he was also appointed Superintendent of Trade Statistics and Inspector-General of Registration. He also served a period as personal assistant to the Financial Commissioner and conducted an inquiry into salt taxation. All of which gave valuable administrative skills for the Tasmanian life that was to follow. As in the Santal Parganas, his work in Oudh saw him spending a great deal of time in the field. He later estimated that he covered about 3000 miles (4800 km) a year on tour.

Braddon’s memoirs show clearly how much he enjoyed the work, the hunting, and the social life of a moderately important civil servant. From all accounts his superiors were pleased with his work. Despite this, an amalgamation of various provinces in 1877 saw his position abolished, and to his annoyance he was forced into a premature retirement the age of 47. His Indian career was over. Incidentally, as well as the hunting book referred to earlier, Braddon also found time to write Life in India, published in 1872, during his years in Oudh. Both of his books are very readable. Perhaps he took after his sister, Mary Elizabeth Braddon, who was one of the most popular English novelists of the second half of the nineteenth century.

At the end of their Indian years, most Anglo-Indians returned home to Britain, where, it has been said, they lived out their lives in relative obscurity in places like Bournemouth or Brighton. Braddon was different, for he had no desire to retire, and he and his second wife, Alice, chose to move to a new home in the Australian colonies. Why did they come south? It seems that an important factor was the work of Colonel Andrew Crawford. During the 1870s and 1880s a number of Anglo-Indians settled in the Tasmanian North-West—not only the Braddons. They did so largely as a consequence of publicity of this area sent back to India by Colonel Crawford. Crawford was himself a former resident of India, an army officer who had settled on the Tasmanian North-West Coast. His efforts at extolling Tasmanian virtues caused a great deal of interest in the Anglo-Indian community, and it seems likely that Braddon was influenced by this. So when the Braddons left India in March 1878 they set off for Tasmania, rather than heading home to Britain.

In Tasmania the couple soon purchased a small, rather run-down property at Leith, on the coastal road between Devonport and Ulverstone. Tasmania’s North-West was largely unpopulated at this time and it has been said that the coastal community was greatly enriched by the arrival of Anglo-Indians families—people who brought invaluable skills and money to the colony. The local society ‘was greatly enriched by these people who had more leisure and taste and money than most to devote to community affairs.’[3] Anglo-Indians left their mark on Tasmania in many ways. For example, three of them entered the Tasmanian Parliament: Andrew Crawford, Edward Braddon and Arthur Young, all before 1900. It is no wonder that people like Braddon were encouraged to stand for the Tasmanian Parliament, because they brought a great deal of experience to the colony.

Braddon’s writings tell us that he and Alice played their part in the local community. Braddon was often seen on the roads around Leith, riding his white horse, in his ‘blue velvet riding coat, a white waistcoat, and light corduroy trousers, [and with] a large carnation hanging from his button-hole’.[4] I remind you we are talking about rural Tasmania here, so he must have seemed quite an exotic flower! Incidentally, within a year of his arrival, Braddon had a series of 30 letters published in the Indian newspaper, the Statesman and Friend of India. These were letters in which he talked at some length about two things: his experience of settling into Tasmanian life, and his view of Tasmania and its possible future. The letters give a valuable insight into life on the North-West Coast at this time. [5]

In 1879 Braddon won the House of Assembly seat of West Devon. He won it by just 22 votes, a close-run thing, and his narrowest-ever victory. He had begun what John La Nauze, the Federation historian, later described as ‘an elegant retirement in the game of colonial politics’.[6] But it was an active ‘retirement’. By 1886 Braddon was Leader of the Opposition, and he served as Minister for Lands and Works in the Fysh Government during 1887 and 1888. What seemed to be the crowning achievement to his Australian career was his period in London as Tasmanian Agent-General between 1888 and 1893. When he left the Agent-General position he was 64, and it was expected that he would settle into retirement in Leith. Instead, as soon as he set foot back on the North-West Coast, he was persuaded to contest West Devon again. He was re-elected promptly. In less than a year he was Leader of the Opposition, and barely a year after that, after the Dobson Government suddenly collapsed in April 1894, Braddon became Premier. He held this position until 1899, despite the fact that his government had not been expected to last long. When it finally lost office in December of that year, it was the longest-serving Tasmanian government to that time.

Several things stand out in the Braddon Government story. After the severe depression of the early 1890s, it helped restore Tasmania’s finances. This was partly due to the severe reduction of the number of Tasmanian public servants. ‘Braddon’s Axe’, as it was referred to, was swung, removing from the public service a great many officers. The Government also encouraged the expansion of industry, and many public works were constructed. It enticed Tattersalls Lotteries from Melbourne to Hobart. Of great later significance, proportional representation was introduced to the House of Assembly elections, the first time it was used in Australia. The Tasmanian historian, John Reynolds, has spoken of the Braddon Government as being ‘a terror to the Hobart clique’ who had long sought to dominate the colony.[7]

A socialist journal, The Clipper, described Braddon in verse:

Keen eyed, quick witted, a man who knows

The way to wheedle friends and vanquish foes.[8]

As Premier, Edward Braddon certainly left his mark, but of course there was more to come, particularly in the area of Australian Federation, and that is where we go for the rest of today’s lecture.

The following illustration is one of the number of simple cartoons of the 1897–8 Federation Convention members published in the journal Quiz.[9] The drawing of Braddon fits another contemporary description of him:

The following illustration is one of the number of simple cartoons of the 1897–8 Federation Convention members published in the journal Quiz.[9] The drawing of Braddon fits another contemporary description of him:

Almost as thin as [Fredrick] Holder [of South Australia], slight, erect, stiff, with the walk of a horseman and the carriage of a soldier, he had the manner of a diplomat and the face of a mousquetaire.[10]

Like many other Tasmanian politicians, Edward Braddon had long supported the union of the six Australian colonies. For over five years he had been a member of the Federal Council of Australasia, serving as president in 1895, and he also hosted the 1895 Premier’s Conference, at which the push towards Federation was officially revived. Nothing came of the constitution drafted at the Convention of 1891, and it was only in the mid-1890s that the move to Federation was reborn, and the 1895 Premiers’ Conference was an important part of that development. Braddon was not only a keen federationist, he was also a keen supporter of imperial federation—the federation of all British colonies under British rule. The ideal of imperial federation had a number of adherents in Australia and elsewhere throughout the British Empire during the late nineteenth century. It is hard to imagine now that the ideal saw colonies like New Zealand, Australia and Canada coming together in an imperial structure, with Britain at its heart. Braddon saw the union of the Australian colonies as the first step along that path, and in 1888 he had helped establish the Tasmanian branch of the Imperial Federation League.

Most of what follows deals with Braddon’s activities at Federation Convention of 1897–8 and thereafter. It was this Convention, held successively in Adelaide, Sydney and Melbourne, which produced most of the final Australian Constitution. Five colonies attended, Queensland being the exception. Braddon was one of ten Tasmanians elected to represent his colony at the Convention’s deliberations.

As the five premiers who attended were to be ex-officio members of all committees at the Convention, it was likely that Braddon would play an important part, and this proved to be the case. By contrast, the remainder of the Tasmanian delegates made little mark. In fact, one measure of Braddon’s relative importance in the Tasmanian contingent is that he spoke for well over one-third of the time taken up by the Tasmanian delegates. Despite this, Braddon was distinctive among politicians of the time—his speeches were usually short! In fact on one occasion at the Melbourne session he actually apologised that he might not have spoken long enough on a particular issue,[11] but I don’t think any of his fellow delegates, used to the lengthy orations of people like Alfred Deakin or George Reid, were bothered by this. In fact, he was occasionally praised for his conciseness.

However, it would have been clear to those listening to Braddon’s contribution at the Convention’s opening that his views, however briefly expressed, reflected the main attitudes to Federation held in the smallest colony.[12] For example, he expressed his belief that the two great advantages of Federation, at least for Tasmania, would be a federated defence arrangement, together with the abolition of customs duties in trade between the Australian colonies. Tasmanians had long resented the fact that they had not been able to get into the Victorian market, which was strongly protectionist. Support for a federated defence and support to the abolition of customs duties were views very widely held across Bass Strait.

However, Braddon also believed that the abolition of internal customs duties was actually dangerous for the smaller colonies and he was adamant that the financial health of these colonies had to be protected in the new constitution. We shall return to this issue.

On another matter (of relevance to our location today on the Senate side of Parliament House) was that Braddon was very much in favour of a strong upper house. He stated consistently that the upper house should be strong and should have a very considerable power to block and amend legislation. As a consequence of that he was one of the delegates who supported the insertion into the Constitution of what eventually became section 24, the nexus clause, where it says that the House of Representatives shall be as nearly as practicable twice the size of the Senate. In addition, he was one of those delegates who believed that the upper house should be called the ‘States’ House’, for he thought that name would get the message home as to what the role of the upper house should be.

Unlike some in eastern Australia, Braddon also believed in the importance of Western Australia coming into the Australian Federation. He said it was important that the Convention delegates make every effort to ensure the participation of that far distant colony. The reason for that seems to have been that he believed that the smaller colonies had a common cause to protect themselves against New South Wales and Victoria, and Western Australia would be an important part of that likely struggle.

On more general issues, where there was not necessarily a small state view, Braddon supported responsible government, as distinct from the US model. His former Attorney-General, Andrew Inglis Clark, himself an important federationist, was very keen on the American model, but Braddon was one who supported responsible government, where the government of the day remains so while it controls the lower house.

Braddon also believed the Senate should be an elected body—unlike some of his colleagues. The 1891 draft Constitution had not made the Senate an elected body, but this was not surprising. At that time the upper houses of the UK, New Zealand and the USA were not elected, and many Australians believed that the same should apply to any new national upper house. Braddon also believed that amendment of the Constitution should be difficult, and he believed that courts should decide disputed elections, taking such electoral matters out of the hands of the politicians. He believed in a uniform franchise across the country, with no favouring of property. At this time Tasmania still did not have full adult suffrage despite his government’s attempt to introduce it, and Braddon was very keen that this should not be the case for Australia as a whole.

Braddon spoke strongly of his belief that the place of public servants should be protected in the new constitutional arrangements. He was one of the few delegates in fact to show any interest in the future administrative arrangements. He also believed that the people should be part of the constitution-writing process by being asked to vote on the Constitution Bill once it was written. He was also in favour of the retention of Privy Council appeals, claiming it would be a ‘lamentable mistake’ were the Convention to weaken ‘one of the strongest links that connect us with the British nation’.[13] This last point is a reminder that like most other delegates, Braddon saw Australia as part of something larger—the British Empire He was, after all, an imperial federalist.

Braddon shared with some other Convention delegates the belief that the Commonwealth government would not be large, for it would have relatively few responsibilities. It might have the defence of the country to worry about, and it might need to mint a few coins or a few stamps, but he thought not much more than that would need to be done by the national administration. Braddon believed it was better not to load the Commonwealth Parliament with tasks like conciliation and arbitration, which were best done at the state level. He claimed that giving the conciliation and arbitration power to the Commonwealth Parliament would be to increase, rather than diminish, the difficulties of industrial disputes. It would possibly interfere with what he called ‘trades unionism’, and it would certainly interfere with employers and employees. All of which meant that something like conciliation and arbitration should remain very much the province of the states, rather than the national government.[14]

Above all else, and like the other nine Tasmanians, Braddon was a small states defender, concerned that a balance should be kept between the need to establish a democratic nation, and at the same time ensuring that the less-populated states were not swamped. As he put it to his fellow delegates:

If I ask for consideration for the smaller States, it is for the one great reason that I want the people in the smaller States to come in [to the new Australian nation]. [15]

There is no doubt that from the perspective of the smaller colonies, there was a need to remain alert, for some of the large colony delegates did not hold the minnows in high regard. Sir Joseph Abbott of New South Wales, for instance, on one occasion denied that the defence issue had any relevance of Tasmania, asserting, ‘a fleet would pass it by without knowing it was there.’[16]

In regard to the ‘small state’ issue Braddon, like many others at the Convention, found New South Wales Premier George Reid difficult to deal with. On a number of occasions Reid attacked the small colonies, expressing his resentment that:

… those who represent a minority of the taxpayers gain their way and mould this instrument, which was designed to express the national will … .[17]

By ‘National’, of course, Reid meant New South Wales. Braddon responded with an attack upon Reid’s ‘ludicrous’ and ‘inexcusable’ charges against Tasmania.[18] Alfred Deakin later wrote of Braddon bringing to the Convention ‘an element of manners’,[19] but on one occasion even the normally diplomatic Tasmanian let fly against large-colony arrogance, asserting angrily that: ‘Size is not everything. A bladder may be large, but there is little in it.’[20]

Despite the provocation from delegates like Reid, it is clear that Braddon’s dry wit helped keep Convention relationships reasonably amicable. His running gag throughout the Convention was of having Hobart designated as the new national capital. At one stage in Melbourne, the Convention considered amendments suggested by the colonial parliaments, including the New South Wales Legislative Council’s claim that the Constitution should designate Sydney as the capital city, a proposal with which William Lyne of New South Wales agreed. Josiah Symon of South Australia countered with the suggestion of Mount Gambier, while Dr Cockburn of the same colony suggested Adelaide. ‘Nonsense’, said Braddon, ‘Nature has fixed upon Hobart as the capital. Everything points to it or some other place in Tasmania as the capital.’ Sir John Forrest of Western Australia was horrified: ‘But you would need a bridge [to get] across [to it]’, he objected. ‘All that would be done by the Commonwealth’, replied Braddon, showing a clear understanding of Tasmania’s future relationship with the national government. ‘Would Launceston do as well?’ asked another mainlander. ‘I will not say anything against Launceston’, said a Premier well-alert to Tasmanian regional rivalries.

To conclude this piece of by-play, Braddon assured honourable members, with tongue in cheek, that after Hobart was selected as the capital city, when members and senators travelled south to take up their parliamentary seats they would ‘be making no sacrifice of health or personal comfort.’[21]

Such an ability to defuse tense situations no doubt helps explain John Downer’s view of Braddon, expressed in a letter to Samuel Griffith of Queensland. Braddon was, said the South Australian, ‘a very charming and interesting man to have at the Convention’.[22] Alfred Deakin described the Tasmanian as an ‘accomplished strategist’ and furthermore, an ‘admirable negotiator’.[23] All of which suggests that Braddon probably played an important part in helping the Convention do its work reasonably smoothly, particularly when its members were away from the Convention floor. At the same time, a reading of the Convention debates shows quite clearly that Braddon never lost sight of who had sent him to the Convention. As the Constitution-writing progressed, the Tasmanian Premier remained ever-alert on the need to defend the place of the smaller colonies. If there is any criticism to be made of him, it would be that he could have spent more time on the big-picture issues than he actually did. In his determination to protect the place of the smaller states, he tended to let others focus on the bigger questions.

In fact it was a result of his determination to look after Tasmania’s best interests that he gained his greatest notoriety—at least on the mainland. The view at home was rather different. Thirty years ago I was talking to an elderly man on the North-West Coast of Tasmania. He was a man who had known Braddon, and as we discussed his career, he suddenly said: ‘You realise of course Braddon was responsible for the “Braddon Blot”?’ For him the memory remained strong, and something for which Braddon deserved praise. Of what was he talking?

As I have said, supporters of Federation were adamant that Australia be rid of the tariffs that separated the six colonies. The major problem here, though, was the great dependence of the colonies on all the tariffs they collected. They were in fact far more important than income taxation at that time: Western Australia gained 91 per cent of its finances from tariffs, Tasmania gained 76 per cent, and even the supposedly free-trade colony of New South Wales gained about 60 per cent of its money from tariffs. The obvious and crucial question for Convention delegates was what would happen to the states’ finances in the new federal nation when internal free trade had been put into place.

A lot of time was spent at the 1891 and the 1897–8 Conventions grappling with this issue, and Braddon was one of the number of small colony delegates who believed that a foolproof way of protecting the finances of the smaller states should be inserted into the Constitution. In due course, Chapter IV of the Constitution was written to achieve this:

- Section 87 said that not more than one quarter of the money raised in customs and excise duties could be used for Commonwealth purposes. The remainder was to be paid to the States, or applied to the payment of interest on State debts if these should be taken over by the Commonwealth.

- Section 93 guaranteed payments to the States for 5 years after a uniform tariff was established.

- Section 94 said that the payment of all surplus Commonwealth revenue was to be given to the States.

- Section 95 allowed Western Australia to remove its tariffs over a five-year period.

- Section 96 gave the Commonwealth the power to make grants to any State for at least 10 years.

Let us go back to the first of these provisions. Something like Section 87 had been suggested in different forms by various delegates throughout the Convention’s three sessions, but nothing had come of it. As the last days of the third session drew near, Tasmanian delegates started to worry that nothing would be done. On the fourth-last day of the Convention, Braddon brought forward the first draft of what eventually became Section 87, and after some discussion it was passed. That section quickly became known at the time as ‘the Braddon clause’. It was carried by a vote of 21 to 18, though New South Wales delegates voted 8 to 1 against it. The Convention came to a close soon after.

Although illness had limited Braddon’s activity at the second session of the Convention in Sydney, his overall contribution had been important. Deakin believed his efforts to have been significant, placing him in what he described as the ‘second rank’ of delegates, in a list that included Bernhard Wise, Henry Bournes Higgins and John Downer.

Braddon’s final address at the Federal Convention was characteristically brief, but gracious. He noted that delegates were all necessarily influenced by the interests of their colonies, but believed this was ‘as natural as it was excusable’. The smaller States had been defeated on the question of the Senate’s power in relation to money bills, but he assured his listeners that they accepted their defeat ‘with gracefulness’. And if the smaller states occasionally lost a battle, ‘well, it has been said somewhere that “Failure is God’s road to success”.’ Braddon expressed his belief that Tasmanians would support the Commonwealth Bill, and he was sure that he and his colleagues could get their fellow Tasmanians to vote to accept the Bill. He ended his time at the Convention with a flourish:

… to my mind it is a Bill which appeals thoroughly to the people, the great masses of the people, for whom we have prepared it … the people will dominate—dominate as they should do, reasonably and in a wholesome way—and nothing will be possible to be done except with the assent of the people.[24]

Braddon’s Federation work did not stop here, for he was soon involved in the two referenda campaigns of 1898 and 1899. Voters were given the opportunity to approve or reject the draft constitution before it was sent to London for parliamentary approval. In Tasmania the referenda campaigns were organised by two Federation leagues—one in the north, and the other in the south of the colony. According to one observer, Tasmanian political leaders such as Braddon, Sir Philip Fysh, Neil Lewis and Henry Dobson, all premiers in their time, were happy to ‘offer themselves as privates in the ranks of the little Federal Army’, being prepared to speak anywhere around the island, wherever or whenever the leagues asked them to. One historian has described Braddon as being in his element, speaking ‘from balconies, buggies and on street corners with an enthusiasm unusual in a seasoned public man’.[25]

As part of his campaign efforts, in May 1898 Braddon issued a manifesto to electors in which he spelled out the reasons for voting ‘yes’ in the forthcoming referendum:

- it would enable ‘this small colony’ to be ‘a sharer in all the advantages that will flow to every province’

- voters were being asked ‘to give up provincialism for a broader national life’

- all people would benefit from free markets

- there would be a demand for labour due to an increase in industrial activity

- there would be ‘security against hostile aggression’

- if Tasmania stayed out, it would suffer as ‘a small fragment of that outside world’ that would be blocked by Commonwealth customs barriers

- in particular, the New South Wales market would be barred to Tasmanian products

- in conclusion, Braddon noted with great pleasure that ‘the Senate [would] exist for the representation and protection of state rights and state interests’, and that, he asserted, ‘as much as anything, commends the Constitution to me’.[26]

A contemporary letter to the Launceston Examiner gives a flavour of Braddon’s efforts. It shows one voter’s feeling of confidence in what the Premier had to say:

On Monday evening last I had the pleasure of being present to hear the Hons. Sir E. Braddon and Mr N. Cameron … Sir Edward, although not at his best, acquitted himself very satisfactorily and carried the very large audience present with him, and I may say that many who had been wavering before, on hearing his views on Federation have now made up their minds to support it. They feel convinced that the Hon. Premier, at his advanced age [of 69], would not advocate the cause if he had the slightest idea it would be a bad bargain for us … .[27]

These words are a reminder of latter-day South Australian Premier John Bannon’s comment that the presence of a stable group of five premiers in office at the time, was important to the advent of Federation, because he believed those five men created trust and co-operation in their own communities.[28]

Two months after the Convention, referenda were held in four of the colonies—Western Australia and Queensland did not move on the matter at this stage. The Commonwealth Bill was accepted by wide margins in Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania. In New South Wales the Bill required not only a ‘yes’ majority, but at least 80 000 votes in favour. There was much opposition to the Bill in New South Wales; Premier Reid wanted to get the message across that his colony would like to come in to the new nation, but it was not going to do so without some concessions.

Many aspects of the Commonwealth Bill were criticised. There was fierce opposition in relation to the powers of the Senate, which was attacked as an undemocratic body. The prospect of an increase in customs duties also upset people, as New South Wales had long prided itself on its free trade policies. But in particular, the finance clauses in Chapter IV were resented, with most vitriol reserved for what the Daily Telegraph had described as a ‘blot’ on the Constitution, namely the ‘Braddon Clause’. This, naturally enough, was soon referred to as the ‘Braddon Blot’. ‘The Braddon Blot’, thundered Labor politician Billy Hughes, was ‘abhorrent to the free trader and detestable to the protectionist’.[29] On polling day the Bill failed in New South Wales, for although there was a majority in favour, the affirmative vote of over 71 000 was short of the required figure of 80 000. Federationists like Braddon were devastated, for the other colonies would not proceed without the ‘Mother Colony’.

The photograph below shows five of the premiers in 1899. In the back row we have Edward Braddon, with John Forrest from Western Australia. Front left is George Turner of Victoria, Charles Kingston from South Australia is in the centre and George Reid is on the right. It is a photograph taken in Melbourne in early 1899 when the Premiers met to discuss the draft constitution. The Premiers had realised that it was important for them to move the Federation process along, but was also important that they be seen to be listening to New South Wales’ concerns. So they met in Melbourne to see if they could push matters to a resolution. This was the so-called ‘secret’ Premiers’ Conference, which was not open to press and public.

|

|

The Five Premiers. Courtesy of the National Library of Australia

|

George Reid was happy that the meeting was taking place, because he used this as the opportunity to delete the ‘Braddon Blot’. In fact, the Blot was retained, because as the Premiers debated the issue, Reid came to realise that all suggested alternatives to the Blot were actually worse than the Blot itself. However, as a compromise, the premiers agreed that Section 87 would operate for ten years, and thereafter until the Parliament otherwise provided. With that Reid had to be satisfied. Referenda were scheduled for later in 1899—Queensland now taking part—though Western Australia still held off giving its voters the chance to have their say.

Braddon was now certain of the acceptance of the Commonwealth Bill, despite having to deal with an attack upon it by the Tasmanian Statistician, Robert Mackenzie Johnston. Presciently, Johnston believed that the finance clauses would not work as hoped, and that the Commonwealth would soon become financially dominant. In response, Braddon and the other Tasmanian federationists were careful not to criticise the highly regarded statistician, but chose simply to assert their faith in the fairness of any future Commonwealth Parliament in its negotiations with the states. In fact, Johnston’s fears may well have been irrelevant to the result. In 1898 Tasmania had voted 81.3 per cent in favour of the Bill; in 1899 support jumped to 94.4 per cent, the highest affirmative vote among the colonies. The outcome suggests that there had never been any real doubt that Tasmania would support the Constitution Bill. All colonies eventually voted in favour, of course, and came together on the first of January 1901.

Edward Braddon had been an important participant in this seminal occasion in Australia’s modern history. A footnote to our story is that he still did not retire, but contested the first election for the House of Representatives. The Tasmanian arrangements were that the state voted as a whole, and with a personal vote of 26.2 per cent, the veteran topped the poll. The 71 year-old was, in effect, the first Tasmanian elected to the House. He remains the oldest from any state to be elected to our national Parliament. He was re-elected in 1903, but seven weeks after that he was dead.

In conclusion, I quote a New South Wales Federation Convention delegate, Joseph Carruthers. Writing 20 years after the events described here, Carruthers obviously regarded Braddon very highly, describing the Tasmanian politician as having

[C]ommanded respect for his views at all times by his quiet and respectful, though determined manner of presenting them to his colleagues.[30]

On 12 May 1951 at Commonwealth Jubilee celebration ceremony in the Devonport Town Hall, Edward Braddon was the Tasmanian honoured for his participation in the achievement of Australian Federation.

Question — May I ask why you chose Braddon above all others?

Scott Bennett — That’s a question that a number of Tasmanians could well ask. When in 1951 Braddon was honoured in the way that I have just described, it caused some unhappiness in Tasmania, because many people believe that Andrew Inglis Clark, who had been at the 1891 Convention, and whose work is seen very clearly in section 51 of the final Constitution, should have been the man so honoured. Why Braddon? Well I think Bannon’s point that the premiers were key players in this is an interesting one, and so Braddon was the one I chose, rather than Clark. Braddon is less well-known than Clark, and he is someone whose career I have long followed.

Question — Since the time of Braddon we’ve had Commonwealth-state financial relations and Premiers’ Conferences, and the states conceded their income-tax power. Since then we’ve had the GST and the way that that revenue is distributed in exchange for the states ceding more of their taxation powers. In a way you could look at Braddon and say that perhaps he was being parochial, or he was thinking of the short term. But perhaps in another way he was putting his finger on an inherent tension that was always going to remain within the federation and is still something we have to grapple with today.

Scott Bennett — I’ve just been writing a paper for the Parliamentary Library on the state of our federal system. When I was looking back at those early years it was so clear to me, having Braddon in my head as well, that within a couple of years of Federation, within a couple of years of 1 January 1901, Deakin was talking about the states being bound to the chariot wheels of the Commonwealth, and he meant in financial terms. The historian John Craig has said that in fact even before the end of the first year of the new Commonwealth, there was disillusionment in Tasmania at least, if not the other states, because it was quite clear that the Commonwealth would become dominant, particularly in financial terms. I think when we look at the history of Commonwealth-state relations since 1901, it’s quite clear that for all that work done, it was for nought, because hardly anything in Chapter IV worked as it was designed to do, and the Commonwealth within a very short time was in fact financially dominant—and has become more and more so.

* This paper was presented as a lecture in the Department of the Senate Occasional Lecture Series at Parliament House on 8 December 2006.

[1] Alfred Deakin, The Federal Story. The Inner History of the Federal Cause 1880–1900. Edited by J.A. La Nauze. Melbourne, Melbourne University Press, 1963, pp. 72–3.

[2] Scott Bennett, ‘Braddon in India’, Tasmanian Historical Research Association Papers and Proceedings, vol. 26, no. 3, September 1979, p. 71.

[3] G.T. Stilwell, ‘Andrew Crawford’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol. 3, Melbourne, Melbourne University Press, 1969, p. 491.

[4] John Reynolds, ‘Premiers and Political Leaders’, in F.C. Green (ed.), A Century of Responsible Government 1856–1956. Hobart, n.d. [1956?], p. 195.

[5] See Edward Braddon, A Home in the Colonies: Edward Braddon’s Letters to India from North-West Tasmania, 1878. Edited by Scott Bennett. Hobart, Tasmanian Historical Research Association, 1980.

[6] J.A. La Nauze, The Making of the Australian Constitution. Melbourne, Melbourne University Press, 1972, p. 103.

[7] Reynolds, op. cit., p. 195.

[8] The Clipper, 30 September 1899.

[9] Quiz, 8 April 1897.

[10] Deakin, op. cit., p. 72.

[11] Australasian Federal Convention, Melbourne session, 11 March 1898, p. 2321. The Debates of the Australasian Federal Conventions of the 1890s are online at www.aph.gov.au/senate/pubs/index.htm.

[12] Australasian Federal Convention, Adelaide session, 24 March 1897, pp. 63–9.

[13] Australasian Federal Convention, Melbourne session, 11 March 1898, p. 2322.

[14] Australasian Federal Convention, Adelaide session, 17 April 1897, pp. 791–2.

[15] Australasian Federal Convention, Adelaide session, 24 March 1897, p. 66.

[16] Australasian Federal Convention, Adelaide session, 13 April 1897, p. 495.

[17] Australasian Federal Convention, Melbourne session, 9 March 1898, p. 2138.

[18] Australasian Federal Convention, Melbourne session, 9 March 1898, p. 2155.

[19] Deakin, op. cit., p. 73.

[20] Australasian Federal Convention, Melbourne session, 1 March 1898, p. 1713.

[21] Australian Federation Convention, Melbourne session, 8 February, 1898, p. 702.

[22] Downer to Griffith, 29 April 1898, Griffith Papers, ADD 452, Dixson Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney.

[23] Deakin, op. cit., p. 73.

[24] Australian Federation Convention, Melbourne session, 17 March 1898, pp. 2479–80.

[25] Reynolds, op. cit., p. 200.

[26] Examiner (Launceston), 28 May 1898.

[27] ‘Federation’, letter to the Examiner (Launceston), 24 May 1898.

[28] John Bannon, ‘South Australia’, in Helen Irving (ed.), The Centenary Companion to Australian Federation. Melbourne, Cambridge University Press, 1999, p. 156.

[29] L.F. Fitzhardinge, That Fiery Particle, 1862–1914: A Political Biography, William Morris Hughes, vol 1. Sydney, Angus and Robertson, 1964, p. 92.

[30] A Lifetime in Conservative Politics. Political Memoirs of Sir Joseph Carruthers. Edited by Michael Hogan. Sydney, UNSW Press, 2005, p. 141.

Prev | Contents | Next

Back to top