PDF version [1,220KB]

Renee

Westra

Foreign Affairs, Defence and

Security Section

20 September 2017

Executive

summary

Australian military operations in Iraq commenced in August 2014

as part of the International Global Coalition to counter the Islamic State in

Iraq and Syria (ISIS). A year later, on 9 September 2015, Prime Minister Tony

Abbott announced Australia would expand its military commitment from Iraq into Syria

to conduct operations against ISIS militants located there. At the time, he

said this would ‘help protect Iraq and its people from [ISIS] attacks inside Iraq

and from across the border’.

Military action in Syria was not explicitly authorised by any UN

Security Council (UNSC) resolution. However, on 10 September 2014,

Attorney-General George Brandis explained the Coalition Government’s legal

basis for these operations. He noted Australian actions were He de ‘firmly grounded in international law’ and

based on the principle of collective self-defence of Iraq under Article 51 of

the UN charter.

At the time, the Government was careful to highlight that Australia’s

military objectives and involvement were limited to targeting ISIS through air

strikes, rather than pursuing any broader political objectives aimed at

unseating the Syrian regime. Under Prime Minister Turnbull the Coalition

Government has continued to emphasise that the objective in Syria is to

‘degrade, destroy and defeat’ ISIS. But beyond this there has been no substantial

public discussion or parliamentary debate about any long-term plan or strategy in

Syria or Iraq, despite the conflict’s evolution and the impending conclusion of

major urban military operations against the group.

Operation Okra is the Australian Defence Force’s (ADF) contribution

to the international, US-led operations against ISIS in Iraq and Syria. As of

June 2017, about 780 Australian personnel are deployed to the Middle East as

part of this mission. They are split across the Air Task Group (the only

element to operate in Syria and Iraq), Task Group Taji in Iraq and the

Iraq-based Special Forces contingent. The ADF contribution is part of a

9,000-strong troop commitment from 23 countries, although 72 nations are part

of the broader Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR) Coalition to counter ISIS and

provide non-military assistance such as finance, equipment, humanitarian and

logistics support.

Throughout the conflict, the overall number of Australian

sorties (or air missions) in Syria has remained relatively constant, although

that effort has been a small proportion of the overall Australian effort in

Iraq and Syria, and an even smaller proportion of the overall—US-dominated—OIR Coalition

effort. To date, the ADF has not been involved in any incidents where

significant civilian casualties have been proven, though the question of responsibility

for civilian casualties is a persistent issue for OIR Coalition operations as a

whole.

The conflict is at a significant turning point as the Iraqi

Government claims victory over ISIS within its territory and the Syrian

Government strengthens its control over areas previously held by the group.

This raises a number of questions around strategy, future intent and the durability

of any current solution, as arguably, while ISIS’s defeat was a necessary

operational goal, it leaves wider strategic issues unresolved. However, while

the Australian Government constantly reiterates the importance of dealing with

ISIS, its intentions remain unclear beyond the destruction of the group,

including in relation to key inter-linked issues such as aid and reconstruction

efforts and the future role of Assad.

Contents

Executive

summary

Introduction

Iraq and Syria—interdependent

conflict

The Australian commitment—summary

Australia’s military contribution

Operational tempo

Rules of Engagement (ROE) and the

operational context

Air strikes

Targeting

Accountability: incidents and strike

reporting

Civilian casualties

Budget

The broader Coalition construct

Coalition rate of effort

Ground operations

Australian ground troops?

The legal basis for Australian

operations

International framework

Self-defence

The international consensus for

action in Syria

Australia’s position

Conclusion

Annex A: OIR Coalition military

contributions in Syria, July 2017

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Dr Etienne Henry, Nicole Brangwin and

Professor Rob McLaughlin for their valuable assistance in compiling this paper.

Introduction

This paper provides a summary of Australia’s military

operations in Syria and an overview of key associated issues, particularly

those relevant to the Parliament. Many of these matters are also relevant to

the conduct of operations in Iraq, but this paper does not specifically address

Australia’s involvement in that theatre.

Iraq and

Syria—interdependent conflict

On 8 August 2014, US-led coalition

military operations against ISIS (also known as Daesh, ISIL and IS) commenced

in Iraq following an urgent request for international assistance from the Iraqi

Government.[1]

This operation was formalised in September under the US designator Operation Inherent Resolve

(OIR). OIR’s mission is described as: ‘by, with and through regional partners,

to militarily defeat ISIS in the combined joint operations area (Iraq and

Syria) in order to enable whole-of-coalition governmental actions to increase

regional stability’.[2]

On 14 August 2014, the Australian Government announced Australian Defence Force

(ADF) operations had begun, with humanitarian aid delivered to civilians in

Iraq.[3]

Air and ground operations in Iraq began soon after.

|

The evolution of the conflict

ISIS’s success across Iraq and Syria has its roots in the chaos that followed the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq, aided by the systemic social, political and security issues present in Iraq and the broader region since that time, though these issues arguably have a more complex, long-term history across the Middle East. Sunni disenfranchisement, continued government corruption and mismanagement of basic services and chronic insecurity have all enabled iterations of the group to survive, despite the efforts of Iraqi forces and the US-led Coalition over a decade following 2003. In this sense, ISIS is a symptom that reflects a set of underlying set of issues, common across the region, rather than a single issue that can be divorced from its context.

While iterations of ISIS existed in Iraq long before it moved into Syria, the civil war and the early sectarianisation or radicalisation of the conflict in Syria meant that ISIS was organised and positioned to take advantage of the Assad regime’s decreasing control over its peripheral regions. This allowed it to take over a number of eastern urban centres relatively easily, often with some level of local support. The group’s deliberate, transnational establishment across eastern Syria and Iraq gave it access to a range of resources, as well as providing a measure of geographic sanctuary or defence in depth. As such, any strategy to defeat ISIS needed to address the threat in Syria as well.

The Assad regime’s increasingly tenuous position throughout 2014–15 continued to see ISIS consolidate its Syrian territory and gain ascendancy over other elements of the Syrian opposition, despite the OIR Coalition’s progress against the group in Iraq. However, the tide began to turn in late 2015 with Russia’s entry into the conflict, which augmented Iran’s and Hezbollah’s support for Assad and bolstered the exhausted regime. It is against this complex background that the OIR Coalition is conducting operations against ISIS and other designated terrorist groups. The US and select allies are also providing support to various parties on the ground, such as the Kurdish-led Self Defence Forces. This support is now limited to those groups fighting ISIS, though it previously encompassed select groups fighting Assad.

|

Initially, OIR Coalition operations focused on Iraq in

response to the Iraqi Government’s request for assistance; however, in

September 2014 the US informed the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) that it

had commenced military operations in Syria to deal with ISIS and Al Qaeda

elements (known as the Khorasan Group).[4]

US air operations in Syria have since been extended to ground operations, which

are publicly announced; however, ground-based involvement by other Coalition

partners has generally remained officially unacknowledged.[5]

The multi-national OIR Coalition has 72 partners; however,

only 23 of these are currently contributing to military operations in Iraq and

Syria, and a smaller number again are or have been involved in Syrian

operations.[6]

While all countries are united in their agreement about the need to combat ISIS,

many have drawn a distinction between involvement in Iraq and Syria due to

issues of legality, popular support and the nature of any potential commitment.

Australia is also one of the 12 members of the small ministerial group that is

convened during meetings of the Global OIR Coalition; many of these members also

have some involvement in Syria.[7]

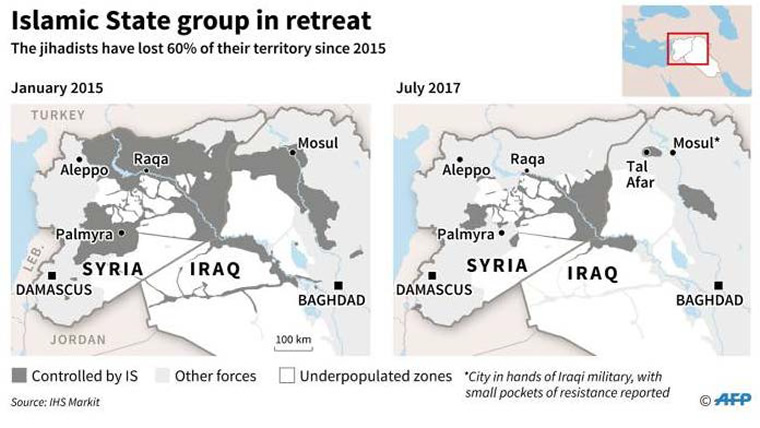

Figure 1: ISIS areas of influence—a comparison from January

2015 to September 2017

Source: IHS Conflict

Monitor and AFP[8]

The

Australian commitment—summary

Augmenting Australia’s initial August 2014 humanitarian

commitment, in March 2015, Prime Minister Tony Abbott announced a contribution

to the international Building Partner Capacity (BPC) mission with an additional

300 regular troops to train Iraqi security forces. By then, the ADF Air Task Group

(ATG) was also flying regular strike and refuelling missions in Iraq, and

around 170 Special Forces advisers were assisting Iraqi troops.[9]

But while operations in Iraq were making progress, the US was still looking to its

allies to provide more support, especially in Syria.[10]

On 9 September 2015, following a request from the US

Government, Prime Minister Abbott indicated Australia would expand its

commitment from Iraq into Syria, with Australian air strikes to be extended to ISIS

targets in eastern Syria.[11]

Although the request came from the US Government, at the time there was media

speculation that the Australian Government had pushed for the invitation.[12]

The Defence Minister explained the Government’s reasoning for the deployment as

follows:

The extension of RAAF flights over eastern Syria is very much

a practical and logical extension of the current operations in that area and is

quite clearly in Australia’s national interest because as we know, Daesh [ISIL]

continue to provide a security threat, not just to Iraq and those regions of

Syria in the Middle East, but it reaches out here to Australia.[13]

Prime Minister Abbott also noted that the extended

operations would mirror the efforts of other allied nations already operating in

Syria. This would ‘help protect Iraq and its people from [ISIS] attacks inside

Iraq and from across the border’.[14]

On 10 September, Attorney-General George Brandis explained the Government’s

legal basis for these operations in the Senate (this is covered in more detail

in a later section of this paper). He stated that the decision was ‘firmly

grounded in international law’, and was based on the principle of collective

self-defence under Article 51 of

the UN charter.[15]

He also noted that the self-defence provisions also applied to non-state actors

like ISIS—an increasingly invoked, though non-traditional, interpretation of

the UN Charter’s use of force provisions.[16]

In a September 2015 editorial in The Australian,

Senator Brandis elaborated on this, echoing sentiments also expressed by Prime

Minister Abbott, stating:

The Iraqi-Syrian border is not a natural frontier—it is

literally a line in the sand, the product of the division of the Middle Eastern

provinces of the Ottoman Empire after World War I by the Sykes-Picot agreement.

The Daesh [ISIL] insurgency does not acknowledge it as an international border

and Daesh militias move across it without impediment. It makes absolutely no

sense, from a military or strategic point of view, to be limited by an

arbitrary boundary that the enemy neither recognises nor respects.[17]

However, the Abbott Government was careful to highlight that

Australia’s objectives were focused on combating ISIS, rather than pursuing any

broader political objectives being discussed by other OIR Coalition partners at

the time. In Parliament on 16 September 2015, Defence Minister Kevin Andrews

reaffirmed that Australian operations in Syria were solely directed at ISIS and

Australia would not be engaging in the broader Syrian conflict, though Prime

Minister Abbott refused to rule out expanded Australian operations in the

future.[18]

But while the Government’s principal objective in Syria was

consistently and clearly stated as being to ‘degrade, destroy and defeat’ ISIS,

there appears to have been little if any serious public or parliamentary debate

in Australia (or by coalition partners) about what constitutes success, when

operations may wind up, or what the Australian role in any reconstruction and

follow-on support efforts may be.[19]

Australia’s

military contribution

Australia’s military participation is designated Operation Okra, and

includes activity in both Iraq and Syria. This falls under the broader Coalition

effort, Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR Coalition), involving the Iraqi Government,

Gulf States and international partners.

As of August 2017, about 780 Australian personnel are

deployed to the Middle East in support of Operation Okra. These personnel are

split across three elements:

- Air Task Group (ATG) of approx. 300

personnel operating in Syria, Iraq and across the Middle East

- Special Operations Task Group

(SOTG) of approx. 80 personnel and

-

Task Group Taji (TG Taji) of

approx. 300 personnel in Iraq.[20]

The ATG is the only element to operate in Syria. The

prospect of further Australian involvement—for example, ground troops—has generally

been ruled out by senior government officials (see ‘Coalition operations: ground

troops’ section in this report for further detail).

Air Task Group (ATG)

The current ATG consists of six F/A-18F Hornets, one E-7A

Wedgetail airborne early warning and control (AWAC) and one KC-30A Multi-role

Tanker Transport (refueller).[21]

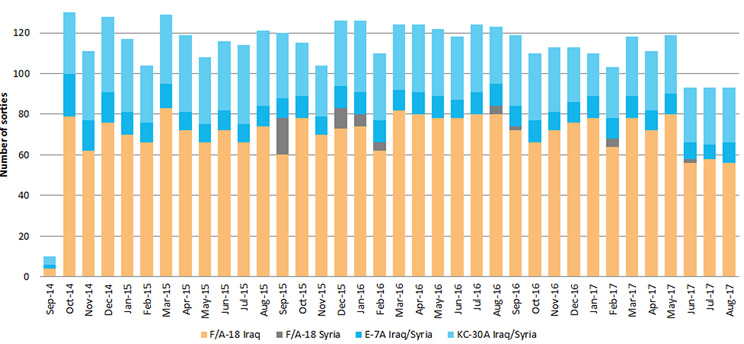

As indicated in Figures 1 and 2, the ATG conducts operations

in both Iraq and Syria:

- From the commencement of operations

to the end of June 2017, the F/A-18 Hornets conducted 50 sorties in Syria, and

delivered 68 munitions. During the same period in Iraq, the ADF conducted 2,399

sorties and 2,100 munitions used.

- The KC-30A refueller entered Syrian

airspace on 116 occasions between September 2014 and June 2017.

- The E-7A AEW&C entered Syrian

airspace 194 times between September 2014 and June 2017.[22]

Australia’s support aircraft assist not only Australian

aircraft during their missions, but other Coalition aircraft as well, which may

partly account for their higher rate of effort.

Operational

tempo

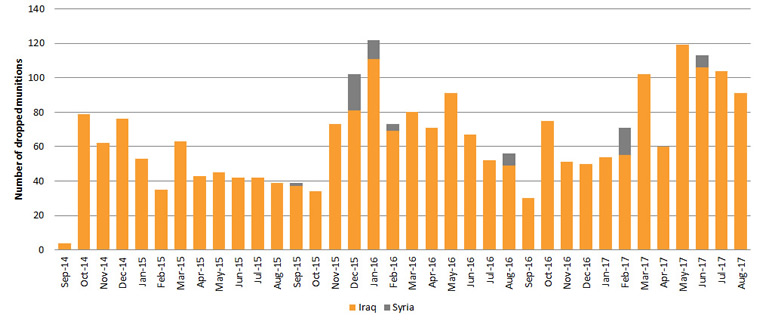

Throughout the conflict, the number of ATG sorties has

remained relatively constant, although the rate of effort in Syria is a smaller

proportion of the overall Australian effort in Iraq and Syria (see Figure 2).[23] From the

commencement of operations to the end of August 2017, the ATG conducted 4,038

sorties and dropped 2,363 unspecified munitions in support of the OIR Coalition

mission in Syria and Iraq.[24]

Syria accounts for 68 of those munitions (see Figure 2).[25]

In Senate Estimates in May 2017, the CDF noted most strike missions employ at

least one weapon.[26]

Figure 2: ADF ATG operations in Syria and Iraq (by number of sorties, platform

and operating location)

Source: Data obtained from HQJOC and collated by the

Parliamentary Library[27]

To give a sense of scale, as at 9 August 2017, the OIR Coalition had flown

a total of 167,912 sorties in support of operations in Syria and Iraq.[28]

However, the Coalition rate of effort has been far more equal across Syria and

Iraq than Australian operations may indicate. This disparity reflects the

greater US effort in Syria in relation to its Coalition counterparts (see Figure

5), though since June 2017 changes in OIR Coalition reporting means the US

effort cannot be distinguished from the activities conducted by other Coalition

partners.[29]

The Chief of the Air Force, Air

Marshal Gavin Davies, noted in 2015 that ATG missions are determined by the

requirements of the Coalition

Air Operations Center (located in Qatar).[30]

In Senate Estimates on October 2015 he said:

... the derivation of targets and the flow within the coalition

determines the rate of effort we fly. But I could categorise that as saying we

do have aircraft flying every day. Sometimes that is: fly the Wedgetail Monday,

not fly Tuesday, fly Wednesday and then the following week it could be fly

Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday but it does vary. It is a fairly steady rate and

has remained that way since we arrived.[31]

Figure 3: Number of ADF-dropped munitions in Syria and Iraq (September

2014 to June 2017)

Source: Data obtained from HQJOC and collated by the

Parliamentary Library[32]

Rules of

Engagement (ROE) and the operational context

US Air Force doctrine provides a good explanation of the purpose behind,

and the principles that determine, national ROE:

ROE constrain the actions of forces

to ensure their actions are consistent with domestic and international law,

national policy, and objectives. ROE are based upon domestic and international

law, history, strategy, political concerns, and a vast wealth of operational

wisdom, experience, and knowledge provided by military commanders and

operators.[33]

While most national operations in Syria are conducted under the

auspices of the OIR Coalition, including those of Australia, each contributing nation

determines its own rules of engagement, which are usually classified for

operational security.[34]

There can also be multiple sets of ROE for different missions or theatres

(especially in a Coalition setting) and ROE can change or evolve in response to

operational requirements.[35]

But generally, all nations are supposed to adhere to the Laws of Armed Conflict

agreed to under the Geneva Conventions, particularly the principles of military

necessity, humanity, proportionality, and discrimination which provide a common

theme to every set of ROE. However, there is still variation within this. For

example, some nations may have zero tolerance for any collateral damage or

casualties while others may be more flexible depending on their doctrinal

guidance, political considerations and what they deem to be ‘proportional’ to

their desired outcome. The CDF, Air Chief Marshal Mark Binskin, summarised this

during a Senate Estimates hearing in May 2017:

The coalition as a whole abides by

the laws of armed conflict—proportionality and discrimination. As to rules of

engagement, each have their national rules of engagement, as you would expect.

Looking across those rules of engagement, there may be some differences in some

areas, but across the board they are relatively similar.[36]

The CDF further clarified that Australia’s rules of engagement are set

by Australia and that the ADF is:

bound by our targeting protocols to

always abide by international law, always operate within our rules of

engagement, and always look to be proportionate, discriminate and ensure that

there is a military advantage from that particular engagement.[37]

However, this is a difficult balance to manage. An OIR Coalition

spokesman noted in a March statement some of the difficulties the Coalition

encounters:

Our goal has always been for zero

civilian casualties, but the coalition will not abandon our commitment to our

Iraqi partners because of ISIS’s inhuman tactics terrorising civilians, using

human shields, and fighting from protected sites such as schools, hospitals,

religious sites and civilian neighbourhoods.[38]

Air strikes

Air strikes (missions during which munitions are released

from an aircraft) can be deliberate or dynamic.[39]

In the context of Syria and Iraq, deliberate strikes are longer-term, planned operations

run from the Coalition Air Operations Center (CAOC) in Qatar while dynamic

strikes respond to short-notice tasking or operational requirements.[40]

As such, a greater amount of work goes into planning deliberate missions and

there is a more limited tolerance for collateral casualties in comparison to

dynamic strikes. Dynamic strikes are conducted at the behest of ground

commanders or intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance assets, generally

in response to an immediate operational need.[41]

It has been suggested that, in addition to the devolution of tasking authority

to lower-level commanders in the field, the increase in dynamic strikes in the

course of operations in Mosul and Raqqa since December 2016 accounts, at least

in part, for the dramatic increase in reported civilian casualties caused by

the OIR Coalition.[42]

Munitions are also chosen for strikes depending on the

desired effect and target. The CDF has noted munition choice can also help to

reduce the potential for collateral damage or casualties—for example, low

fragmentation munitions can be used in urban areas.[43]

On 14 September 2015, Defence Minister Kevin Andrews confirmed the ATG had

completed its first strike against an ISIS target in eastern Syria, with an

F/A-18 destroying an armoured personnel carrier hidden in a compound (ATG strikes

in Syria are annotated in Figure 2).[44]

Until May 2017, Defence did not publicly release details of what ATG strikes

were achieving beyond the number of munitions dropped, unless specifically

noted by the Government (see the ADF strike-reporting section for further

detail).

Combat aircraft conducting missions in Syria also operate

with airborne early warning and control aircraft (AWAC) and other supporting

aircraft, such as refuellers.[45]

This enables aircraft to operate for extended periods of time and maintain

situational awareness of the operational environment. These capabilities also help

deconflict potential issues in Syrian airspace, where Russian and Syrian regime

aircraft also operate. But while the CDF noted in 2015 that the focus of Russian

and Syrian regime forces on central Syria reduced the prospect of potential

issues for any Australian aircraft, the Assad regime’s increasing control over

its peripheral regions has seen Syrian and Russian aircraft operate across more

of the country, potentially changing this dynamic.[46]

The US takes the lead—on behalf of the Coalition—working with Russia to

deconflict operations and Syrian airspace, and there is a direct communication

line between the CAOC and the Russian Air Operations Center.[47]

Targeting

In addition to ROE, the CDF’s Targeting Directive (or TD) also provides

more specific directions for targeting in support of an operation. The ADF

ADDP 3.14 Targeting notes that this directive specifies categories of

target, collateral damage estimation methodology, the levels of risk authorised

for use by designated commanders, command and control arrangements and national

policies on legal issues.[48]

In regard to collateral casualties, the Australian Defence Doctrine Publication

states:

The principle of proportionality

(as with the principle of ‘military necessity’) involves an implied concession

that collateral casualties and damage may in certain circumstances be

justified. That is, just because collateral casualties or damage may occur, or

are even expected from an attack on a military objective, does not necessarily

make that attack unlawful, provided those collateral effects are proportional

to the military advantage.[49]

On 1 September 2016, Prime Minister Turnbull and Minister for Defence

Marise Payne released a statement confirming the ADF ‘now had full authority to

target all members of Daesh [ISIS], in accordance with international law’.[50]

However, the Bill to make the necessary changes to Australia’s domestic laws

was only introduced to Parliament on 12 October 2016.[51] The Criminal Code Amendment

(War Crimes) Bill 2016 aimed to fix an issue that had reportedly been

problematic during ADF operations where non-state actors were involved as

belligerent parties—perhaps the defining feature of recent conflict.

The Turnbull Government’s amendments to the Criminal Code were designed

to allow the ADF to target ‘those who may not openly take up arms but are still

key to ISIS’s fighting capability’.[52]

This also reflects a broadening of the ISIS target set as the OIR Coalition’s

campaign has forced changes in the manner and form in which ISIS operates. The

Australian Parliamentary Library’s Bills Digest on the amendments, explains the

nature and purpose of the changes:

The Criminal Code Amendment (War Crimes) Bill 2016 (the Bill)

proposes to amend the war crimes offences in Division 268 of the Criminal Code Act

1995 (Criminal Code) to address some anomalies in the

treatment of acts done in the course of a ‘non‑international armed

conflict’[1] with the requirements of international humanitarian law

(IHL). These anomalies (detailed below) are said to limit the capability

of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) to undertake international security

operations, and may expose members of the ADF to domestic criminal liability

despite acting in compliance with the requirements of IHL.[53]

Prime Minister Turnbull also elaborated on the nature of

this amendment in a speech to the Queensland Liberal National Party State

Conference:

This legislation for the first time enables our soldiers and

aviators in the field in the Middle East to kill terrorists wherever they are,

not simply when they've got a gun in their hand. Where there was a legal

barrier to them having unrestricted targeting access, as soon as that was

raised with me, I dealt with it. I got on with it and dealt with it.[54]

The Bill passed both Houses of Parliament relatively quickly to become

law on 7 December 2016.[55]

These changes do not appear to have had any impact on the ATG’s rate of effort

or activity in Syria (see Figure 2).

Accountability:

incidents and strike reporting

ADF strike reporting and transparency

On 2 May 2017, the Department of Defence announced a change

in the operational reporting publicly released by Headquarters Joint Operations

Command (HQJOC). This followed the OIR Coalition’s March review of its own strike

reporting.[56]

These changes came at a time of heightened media interest in the increased

number of civilian casualties resulting from operations in Mosul, in which the

ADF had participated.[57]

Until May 2017, Defence only released its monthly sortie and

munition numbers, making it impossible to publicly verify any reports of ADF

involvement in alleged incidents unless the Government specifically addressed an

incident or allegation. In May’s Senate Estimates, the CDF pointed out that the

detail on any strikes conducted by Australians was still reported under the

banner of OIR Coalition reporting.[58]

However, that reporting did not, and still does not, distinguish individual

nation activity—this makes it impossible to verify any allegations or incidents

against the public record. This is one of the main reasons that the widely

cited non-government organisation (NGO), Airwars, ranked Australia as one of

the least transparent nations in the OIR Coalition in its December 2016 transparency audit of the

Coalition air war.[59]

Although there was no admission that the media interest

surrounding operations in Mosul sparked the changes in reporting, from May 2017

HQJOC has been releasing fortnightly reports with significantly more detail on

ATG operations.[60]

Specifically, the reports state the location and nature of targets in any

F/A-18 strike operation, increasing the amount of specific information

available publicly about the targets and outcomes of ADF strikes in the region.

This has, at least in part, solved the issue outlined above and brought

Australia’s level of transparency closer to that of other key OIR Coalition

partners. Throughout the conflict, many OIR Coalition partners, including the US, UK,

Canada,

and France, have generally provided more detail on their missions, targets and

outcomes relative to Australia.[61]

They argue that the provision of such information does not compromise

operational security or their mission, and that the need for transparency and

accountability is important.

However, as Australia has increased its individual level of

transparency, the Coalition has moved to provide less information on the

relative activity of nations within the OIR construct. Since June, the US has

stopped distinguishing between its strikes and those of its allies, and figures

are now only given as Coalition totals (this also makes Figures 4 and 5 impossible

to update). Several news reports note that these changes were a result of media

interest in the casualty figures during the Mosul operations, and that they

effectively absolve Coalition allies from having to account for any casualties

not specifically caused by the US.[62]

Up until this point the US was one of the more transparent nations in the OIR

Coalition—certainly, it was the only one to admit causing civilian casualties.[63]

But while the ADF’s recent release of additional strike information has

increased the level of transparency around the location and type of air

operations conducted in Syria and Iraq, broader questions about the relative

lack of transparency remain, given the disparity with the level of information

shared by most allies. The limited release of information from the Department

of Defence has also been replicated in Parliament. While regular updates on ADF

Operations were given in Parliament by defence ministers John Faulkner and Stephen

Smith under the Rudd and Gillard Labor governments, the Abbott and Turnbull Coalition governments have

decreased the number and detail of operational updates provided to Parliament,

with the last Defence Portfolio Ministerial update provided to Parliament in September

2015.[64]

Civilian

casualties

The reportedly high number of civilian casualties resulting

from Coalition air strikes has been an issue of ongoing concern in this

conflict, although it is broadly recognised that the urban nature of the war

and ISIS tactics exacerbate the potential for civilian casualties.[65]

Air campaigns in Libya, Syria, and Yemen show that civilian casualties are not

only likely, but inevitable in this type of campaign, regardless of the measures

that are taken to avoid them.[66]

However, even the UN has expressed concern over the conduct

of the air campaign in Iraq and Syria, asking whether all measures have been

taken to minimise the loss of life.[67]

Experts, analysts and the media also continue to ask about the disparity

between the number of casualties recorded by NGOs and those recorded by the

Coalition.[68]

The NGO AirWars estimates that from the beginning of operations in 2014 to 8

August 2017, between 14,056 and 20,543 civilians are likely to have died in 1,995

separate reported Coalition incidents in Iraq and Syria, which it notes means the

OIR Coalition is responsible for more civilian deaths than Russia.[69]

Notwithstanding the significant challenges in verifying casualties, this estimate

is radically different to the total of 603 for which the OIR Coalition assesses

it has been responsible since the beginning of military operations in August

2014.[70]

To date, the US is the only Coalition nation to admit it has

inadvertently killed civilians. The US, through the Combined Joint Task Force,

Operation Inherent Resolve (CJTF-OIR), releases a monthly

civilian casualty report which addresses allegations that Coalition strikes

have resulted in civilian casualties.[71]

However, there remains a number of confirmed civilian deaths attributed to

Coalition strikes for which the US does not take responsibility, which

effectively attributes them to allies. In its April 2017 monthly casualty

report, US Central Command (CENTCOM) stated, ‘additionally, it is assessed that

80 civilian casualties attributable to Coalition strikes to defeat ISIS in Iraq

and Syria from August 2014 to the present had not previously been announced’.[72]

A joint Foreign Policy-Airwars investigation notes

that CENTCOM officials confirmed these deaths were attributed to allies.[73]

None of the 12 counter-ISIS Coalition partners that have operated in Syria—including

Australia—have publicly conceded any role in these incidents, nor any others

that have resulted in civilian casualties. However, the ADF did note in May

2017 that Australian strike aircraft have been involved in a small number of

incidents resulting in credible claims of civilian casualties, though none have

been confirmed. Reinforcing the level of care taken in its own procedures, the ADF

specifically stated:

Prior to an air strike,

Australia’s Air Task Group undertakes meticulous and comprehensive mission

planning including national and international approvals. Once a mission is

complete, ADF staff thoroughly review every weapon strike to ensure the strikes

are consistent with pre-strike approvals.[74]

In Senate Estimates in May 2017, the Director-General of the

ADF Legal Service, Air Commodore Hanna, also noted the following ADF processes

in relation to civilian casualty incidents:

If there were allegations in relation

to laws of armed conflict violations made against the ADF, those allegations

would be covered, firstly, through our notifiable incidents reporting. There is

capacity for it to be moving into the investigative processes both within the

Australian Defence Force and wider. You may recall that over the last number of

years, where there have been allegations of civilian casualty incidents, that

is where the Australian Defence Force has been conducting its own inquiries

into each of those events.[75]

But the predominantly air-only nature of the war in Syria

makes any investigative process extremely difficult as post-strike assessments

are often based on surveillance video analysis. Investigators do not have the

same access as they did in conflicts like Afghanistan.[76] This is likely true of

Australian strike review processes in Syria. ABC News also detailed an

ADF response to a Freedom of Information Act request where it was noted that

the Government ‘does not specifically collect authoritative (and therefore

accurate) data on enemy and/or civilian casualties in either Iraq or Syria and

certainly does not track such statistics’ (as the OIR Coalition does this).[77] The OIR

Coalition said in April nations are responsible for tracking this data

themselves, which raises some questions about the gap between these two stated

processes.[78]

In June 2017 the OIR Coalition changed its strike and

incident reporting so that the activities of individual nations (of the US and

its allies) can no longer be distinguished in overall reporting, arguably

reducing the level of transparency for all nations involved and avenues for

victims to seek compensation.[79]

18 September 2016 strike on Syrian Government troops

On 18 September 2016, Australian aircraft were involved in

Coalition-led air strikes targeting what were believed to be ISIS fighters near

Dayr az Zawr, Syria. However, these later turned out to be Syrian Government,

or Syrian Government affiliated troops—the exact nature of which remains

unclear (this reflects the complexity of the Syrian conflict environment and the

number of semi-official militias and groups that have fought for the Assad

regime).[80]

In November 2016, the Chief of Joint Operations, Vice

Admiral David Johnston, relayed the findings of the Coalition investigation

into the incident. He noted that two F/A-18 combat aircraft and one E-7A

AW&C Controller had been involved, but the investigation found that the

strikes were conducted in full compliance with the rules of engagement and Laws

of Armed Conflict. While there had been no disregard of targeting procedures,

several recommendations were made to improve the targeting processes in the

Qatar-based CAOC and reduce the possibility of future targeting errors.[81] Discussing the

incident at Senate Estimates in October 2016, Acting CDF Vice Admiral Griggs

highlighted that ‘we [the ADF] have been patently clear that Australia would

never intentionally target a known Syrian government military unit or actively

support Daesh’.[82]

Defence Minister Marise Payne also said Australia would

never intentionally target a known Syrian military unit or actively support ISIS.[83]

This reflects the restricted objectives and mandate of Australian operations in

Syria, limited to targeting ISIS in the collective self-defence of Iraq.

Budget

The 2017–18 Department of Defence budget allocated $453.6 million to

Operation Okra for the 2017–18 financial year.[84]

The estimated actual cost of Operation Okra for 2016–17 was $353.9 million.[85] The operational

costs provided in the Defence Portfolio Budget Statement are additional costs.

That is, they are additional to the already existing costs of personnel and

equipment. Note that elements of Operation

Accordion provide support to Operation Okra as well as other ongoing

operations in the Middle East Region. There is no way to separate the cost of

operations in Iraq from the cost of those in Syria. The Australian Strategic

Policy Institute (ASPI) stated in its latest Defence budget review publication,

The Cost of Defence, that the ‘cumulative real cost’ of Defence

operations against ISIS in Iraq from 2014–15 to 2019–20 was approximately $1.3

billion.[86]

The OIR website notes that as at 30 June 2017, the total cost of US operations

related to ISIS since kinetic operations started in August 2014, is US$14.3

billion. The average daily cost over 1,058 days of operations is US$13.6

million.[87]

The broader

Coalition construct

The OIR notes that as at 30 June 2017, there were 9,000

troops from 23 countries supporting efforts to defeat ISIS in Iraq and Syria.

Eleven of those countries have conducted some form of operations in Syria

itself. But frontline military support is only one form of contribution. Other

contributions to the mission have come in the form of financial, equipment,

humanitarian and logistics support. The military commitment and activity of OIR

Coalition nations has also varied given the different national caveats in

place, tolerance for risk, and likely variation in national rules of

engagement. Each nation decides its own rules of engagement.

The following countries have conducted air strikes in Syria:

Australia, Bahrain, Canada, Denmark, France, Jordan, the Netherlands, Saudi

Arabia, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, the UK and the US.[88]

But not all have an ongoing commitment (see Annex A for more specific

information on individual contributions). The US, UK and France have provided the

largest most consistent contributions.

Many other Coalition countries, for example Canada, Germany

and Poland, provide ‘enabler’ capabilities such as air-to-air refuelling, and

surveillance and reconnaissance assets. These capabilities support Coalition

air operations. Since October 2016, NATO has also provided direct AWAC support

to the OIR Coalition; however, NATO leaders have sought to highlight that such

assistance ‘does not make NATO a member of this coalition’.[89]

It is misleading to try and order the relative size or

impact of contributions—personnel numbers can fluctuate, national contributions

vary over time and troops may be put to different tasks. Additionally,

personnel are spread across a variety of supporting locations and platforms (for

example, ships). The rotation of the French Carrier Group in and out of the

operation can, for example, have a significant impact on the number of French

troops and capabilities ‘assigned to the mission’, though it is not an ongoing

role in the way that the Australian Task Group’s role is.

See the Coalition contributions table at Annex A for more

detail on the operations of the individual countries involved.

Coalition

rate of effort

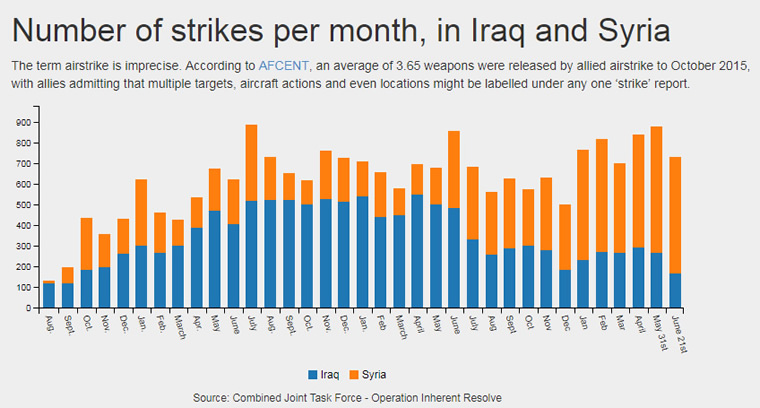

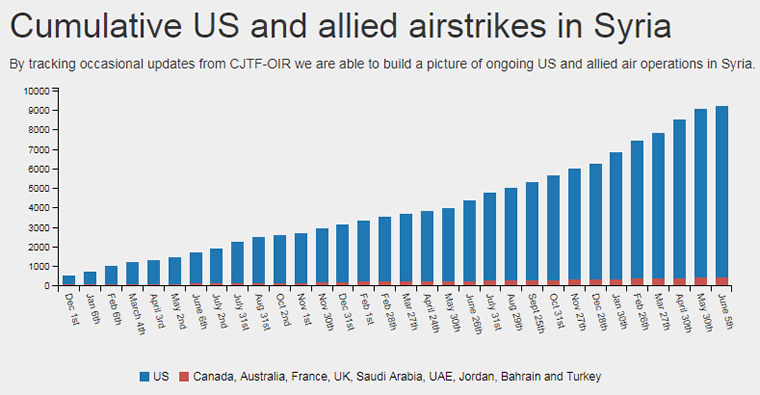

As at 21 June 2017, the OIR Coalition had conducted 18,117 strikes in Iraq and Syria, 440 of which were

conducted in Syria by non-US Coalition members—Figure 4 gives an indication of

the overall Coalition effort in terms of strikes/targeting and Figure 5 shows

the relative level of US effort compared to other allies.[90]

Since June, Coalition reporting has not separated the activity of the US from

its allies, which makes this graph impossible to update. Strike numbers also

include ground artillery activity in Syria, which distorts any comparisons with

the data of previous months. But it is likely the US continues to conduct the

vast majority of strikes on behalf of the Coalition.

The bulk of the OIR Coalition’s air activity remains focused

on Syria, and strikes in Syria have outnumbered those conducted in Iraq since

mid-2016 (see Figure 4). [91]

It is worth noting that in all these discussions and

comparisons the term ‘strikes’ as used by the US does not equate to either

munitions or sorties for which specific Australian figures are publicly available.[92] Multiple

aircraft munitions drops and locations could be included in one ‘strike’. Therefore,

it is not possible to make any specific judgements about the exact proportion

of Australian efforts within the OIR Coalition, though Figure 5 still provides

a sense of scale.

Figure 4: Number of strikes per month, in Iraq and Syria.

Source: Airwars

Figure 5: Relative number of US and allied air strikes in Syria

Source: Airwars

Ground operations

The US has also carried out a range of ground-based operations

supporting local forces and targeting ISIS and other extremist groups in Syria.[93]

This has more recently involved conventional troops (not just Special Forces),

which are effective, easier to deploy and increasingly the capability-of-choice

in complex environments. Other OIR Coalition members have played no publicly

acknowledged role in US ground operations, though Special Forces from multiple

OIR Coalition countries have allegedly been involved in targeting and training

operations (see below).

The presence of US ground troops in Syria has been well-documented

and officially acknowledged since October 2015 when the first group of Special

Forces to operate in Syria was announced.[94]

In December 2016, US Defence Secretary Ash Carter announced that the US would

deploy an additional 200 troops to Syria, supplementing the 300 Special Forces

troops already there ‘advising and assisting’ in the fight against ISIS.[95]

Carter stated that in addition to providing training, US Special Forces would ‘over

time, be able to conduct raids, free hostages, gather intelligence, and capture

ISIL leaders’ and eventually conduct unilateral operations in Syria.[96]

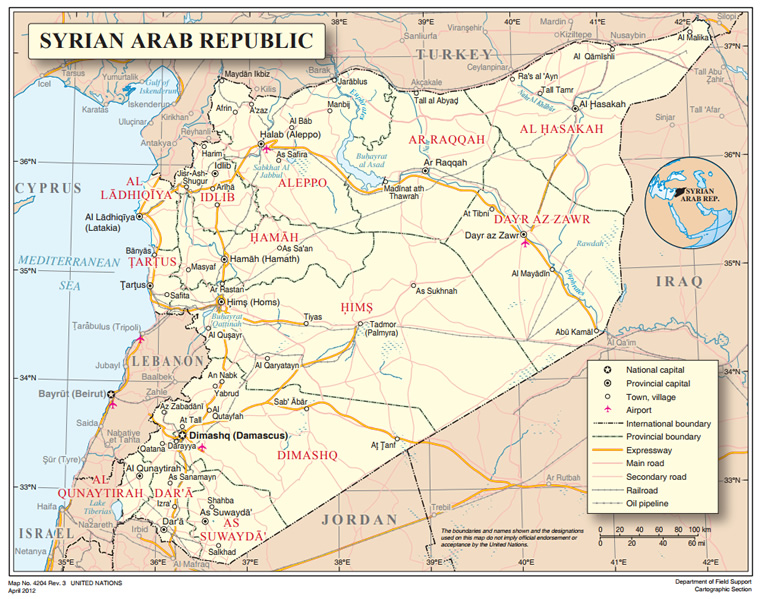

US troops have been operating with Kurdish forces in the

vicinity of Manbij Northern Syria (see Figure 6) since March 2017. While the

Pentagon no longer releases specific troop numbers, a spokesman noted in June 2017

that ‘hundreds’ of US troops were involved in the operation to retake Raqqa.[97]

US forces have also been in the al Tanf Area (on the Jordanian border) for some

time, training and advising Syrian partner forces engaged in the fight against

ISIS.[98]

There has been no indication of what may be planned for these troops following

the conclusion of operations in Raqqa.

In August 2016, UK Special Forces were pictured in Syria in the

vicinity of al Tanf, although, in line with standard policy on Special Forces

operations, there was no comment from the UK Government.[99] There have also been

reports of French and German Special Forces operating in northern Syria, though

the German Government denied these reports.[100]

There have been no reports of Australian Special Forces conducting similar

activities.

Figure 6: The Syrian Arab Republic

Source: UN

Cartographic Section

Australian

ground troops?

In 2015 Prime Minister Abbott

refused to rule out the deployment of ground troops to the broader fight in

Iraq or Syria; however, Defence Minister Kevin Andrews later confirmed that the

Government was not considering any such deployment to Syria.[101]

In October 2015, the CDF explained in Senate Estimates the nature of the ADF’s

commitment in Syria, stating that it was ‘not even so-called; we do not have

boots on the ground’.[102]

Two years later, in a February 2017 interview, Foreign Minister Julie Bishop

also confirmed ‘Australia did not have boots on the ground [in Syria] in the

common understanding of the term’.[103]

The common understanding of the term—which is by no means definitive—is

generally taken to mean troops that can engage in direct combat. It generally does

not refer to train-and-advise missions even though those troops can (and often

do) technically accompany those they train to the front lines.[104]

The legal basis for Australian operations

International

framework

Article 2, paragraph 4 of the Charter of the United Nations states:

All members [UN member states]

shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force

against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in

any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations.[105]

While the intent of the UN Charter is to prevent conflict

between states, there is generally broad acceptance of three exceptions to

Article 2, or legal justifications for the use of force (although this is still

subject to a level of interpretation and they are not all explicitly spelt out in

the Charter). These are:

- consent

(including an invitation from the state seeking specific foreign military

support)

- Chapter

VII authorisation by the UN Security Council (UNSC) (under Articles 39, 41 and

42 of the UN Charter) or

- the

right of individual self-defence or collective self-defence (Article 51).

States might draw on

one or a number of these exceptions to justify military action in another state.[106]

For example, OIR Coalition members have justified their operations in Iraq

under the consent and Article 51 collective self-defence provisions.[107]

Self-defence

The right to self-defence is universally accepted and

enshrined in international law as an exception to the general prohibition on

the use of force by states. Self-defence can be

individual or collective—NATO’s collective self-defence treaty is a classic

example of this.[108]

The criteria for what constitutes self-defence are drawn

from both conventional and customary international law sources (which include

the UN Charter, pre-charter customary law and post-charter customary law).[109]

Professor of Public International Law at the University of Reading, James Green,

notes:

Taken together, these sources of law

provide the three primary criteria against which self-defence claims must be

tested (armed attack, necessity and proportionality), as well as two additional,

secondary, criteria (reporting to the Security Council and the expiration of

the right once the Security Council has taken action).[110]

However, the scope and circumstances in which the right of

self-defence is used is still subject to debate.

Since the September 11 attacks in particular, the use of force in self-defence

has been continually applied to new circumstances involving non-state actors,

namely international terrorist groups, although the traditionally accepted

interpretation of Article 51 is that armed attack had to be ascribed to a state.[111] The limitation of the Article

51’s provisions, namely that it can only be applied to state on state conflict,

was reaffirmed in the 2004 judgment of the International Court of Justice in Armed Activities on the Territory of the Congo (Democratic Republic

of the Congo v. Uganda), which has technically not

been overturned.[112] But

an increasing number of states have supported a broader interpretation of the

right to use force in self-defence to intervene against non-state actors

whenever and wherever they operate. In a 2017 speech on the modern law of self-defence,

the UK Attorney-General noted:

Many states now hold the view,

and have acted on the basis, that the inherent right of self-defence extends to

the use of force against non-state actors, and includes the right to use force

in response to both an actual and an imminent armed attack by that non-state

actor.

A number of states have also

confirmed their view that self-defence is available as a legal basis where the

state from whose territory the actual or imminent armed attack emanates is unable or unwilling to prevent the attack or is not in effective control

of the relevant part of its territory.[113]

However, there is some

reluctance to accept these changing interpretations of when and how the right

to self-defence can be invoked as new precedents in international law—particularly

as these form the core of the OIR Coalition’s justification for operations in

Syria. There is also an argument to be made that the lack of comment from

states in regard to this interpretation of self-defence also does not indicate

acquiescence or solid acceptance of this as a new precedent.[114] For example, the Non-Aligned

Movement, comprised of around 120 states, has expressed its collective reservations

about the gradual expansion of the definition in which use of force is

permitted. In February 2016, in an open debate before the UN Security Council,

the Movement reaffirmed that ‘consistent with the practice of the UN and

international law, as pronounced by the International Court of Justice, Article

51 of the UN Charter is restrictive and should not be re-written or

re-interpreted’ (S/PV.7621, 15 February 2016, at 34).[115]

This tension surrounding

the expansion of the criteria under which states use force in self-defence

is a challenge for the international legal order. Many are concerned this new interpretation

broadens the criteria against which self-defence claims are made, especially

given the definition or classification of a terrorist group is more subjective

than that of a state. For example, Turkey has repeatedly invoked the right of

self-defence to conduct operations in northern Iraq against the Kurdistan

Workers Party (PKK), arguing that the Iraqi Government has been unwilling or

unable to deal with the threat.[116]

This is the same justification Iraq used to push

for the OIR Coalition to use force in Syria, while repeatedly condemning the

Turkish actions in northern Iraq.[117]

The international consensus for action in Syria

The legality of foreign military activity in Iraq is broadly

accepted given that the Iraqi Government’s 2014 invitation requesting assistance

provided a clear mandate, or consent.[118]

However, the justification for the use of force in Syria is more complex even

though it is ostensibly based on the same Iraqi invitation and (albeit

expanded) collective self-defence principles. For a number of states,

operations in Syria are also a matter of individual self-defence (discussed

further below).

The UNSC has not provided any form of explicit legal cover

for military operations in Syria as Russia and China, with their veto powers as

permanent UNSC members, have opposed any form of Chapter VII mandate. However,

a number of resolutions have been passed by the UNSC condemning the violence

and urging member states to take all action possible against ISIS, including resolutions

2170,

2178, 2199

and 2249.[119] Resolution

2249 specifically labelled ISIS an ‘unprecedented threat’ and called upon

member states with the capacity to do so to take all necessary measures to

prevent and suppress the group in Syria and Iraq. Many legal authorities note that

the wording of this resolution provided a level of ambiguity on the use of

force which could be taken to provide political support for such action, even though

the UNSC did not legally endorse such a response.[120]

The key text is as follows:

... calls upon Member States that have the capacity to do

so to take all necessary measures, in compliance with international law, in

particular with the United Nations Charter, as well as international human

rights, refugee and humanitarian law, on the territory under the control of

ISIL also known as Da’esh, in Syria and Iraq, to redouble and coordinate their

efforts to prevent and suppress terrorist acts committed specifically by ISIL

also known as Da’esh as well as ANF, and all other individuals, groups,

undertakings, and entities associated with Al Qaeda, and other terrorist

groups, as designated by the United Nations Security Council, and as may

further be agreed by the International Syria Support Group (ISSG) and endorsed

by the UN Security Council, pursuant to the Statement of the International

Syria Support Group (ISSG) of 14 November, and to eradicate the safe haven they

have established over significant parts of Iraq and Syria.[121]

As such, all OIR Coalition members operating in Syria have

justified their actions on the basis of the collective self-defence of Iraq,

given that ISIS had established bases in Syria which presented a direct threat

to the security of Iraq and Iraq invited the US to assist. In a letter to the

UNSC the Iraqi representative stated:

As we noted in our earlier

letter, ISIL has established a safe haven outside Iraq’s borders that is a

direct threat to the security of our people and territory. By establishing this

safe haven, ISIL has secured for itself the ability to train for, plan, finance

and carry out terrorist operations across our borders. The presence of this

safe haven has made our borders impossible to defend and exposed our citizens to

the threat of terrorist attacks. It is for these reasons that we, in accordance

with international law and the relevant bilateral and multilateral agreements,

and with due regard for complete national sovereignty and the Constitution,

have requested the United States of America to lead international efforts to

strike ISIL sites and military strongholds, with our express consent. The aim

of such strikes is to end the constant threat to Iraq, protect Iraq’s citizens

and, ultimately, arm Iraqi forces and enable them to regain control of Iraq’s

borders.[122]

Another component of this justification is the notion that Syria

was unable or unwilling to prevent ongoing armed attacks by ISIS on Iraq,

though not all states participating in operations mention this doctrine.[123]

As such, other states argue they are justified conducting operations in Iraq’s

defence beyond Iraqi borders because they are acting in collective self-defence

of Iraq. This raises questions of whether consent could have been obtained from

Syria—this was not ruled out by Damascus—or whether the country’s ability to

deal with the threat of ISIS may have now changed, although these issues are

far too complex to explore in the context of this paper.[124]

Any notion of Syria ‘passively consenting’ to Coalition military operations was

also dashed when Damascus singled out the US, UK and Australia for conducting air

strikes in what they regard as a blatant violation of Syrian sovereignty, and the

Syrian Foreign Minister stated on 6 February 2016 that any foreign ground

troops entering Syria would ‘return home in wooden coffins’.[125]

The US, UK, France and Turkey have also used an additional,

individual self-defence justification, noting that the presence of terrorist

groups in Syria is a direct threat to their homelands.[126]

The US stated as much in 2015 following strikes against the Khorasan Group (although

it has since referenced self-defence in a broader context). The UK did the same

following an air strike it conducted on a British citizen in 2015, as did France

following the Paris attacks.[127]

Australia’s

position

The Government of Iraq’s request for assistance in combating

ISIS, based on the principle of collective self-defence under Article 51 of the

UN Charter, forms the basis of Australia’s legal justification for operations

in Syria.[128]

On 10 September 2015, the day after Prime Minister Abbott announced operations

would be expanded into Syria, Attorney-General George Brandis advised the

Senate of the Government’s legal basis for the action, saying that it:

relied, as did other

participating members of the international community, upon the principle of

collective self-defence in article 51. That principle applies to non-state

actors and can extend, in an appropriate case, beyond the borders of the

requesting state.[129]

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade talking points,

obtained under a FOI release, noted that the Government considers there to be ‘a

clear legal basis for striking Daesh [ISIS] targets in Syria: the collective

self-defence of Iraq’ and that ‘our allies and partners have cited this legal

basis for their operations’.[130]

Specifically, the US, the UK and Canada all cited as justification the collective

self-defence of Iraq in letters to the Security Council relating to action in

Syria.[131]

A key component of this justification was that Syria was unable or unwilling to

prevent ongoing armed attacks by ISIS into Iraqi territory.[132]

The Australian Government informed the UN of its intention

to conduct operations in Syria via a letter dated 9 September 2015,

highlighting that the focus of its operations would be to support Iraq in its

fight against ISIS. The letter to the UN stated:

In response to the request for

assistance by the Government of Iraq, Australia is therefore undertaking

necessary and proportionate military operations against ISIL in Syria in the

exercise of the collective self-defence of Iraq. These operations are not

directed against Syria or the Syrian people, nor do they entail support for the

Syrian regime. When undertaking such military operations, Australia will abide

by its obligations under international law.[133]

However, the Australian Government also provided some

parameters on the broader action. During a 9 September 2015 press

conference, Prime Minister Abbott noted that Australia had ‘no legal basis, at

this point in time, for wider strikes in Syria’ (beyond ISIS targets in eastern

Syria), and Defence Minister Andrews noted on 16 September that ‘we will not be

engaging in the broader conflict in Syria’.[134]

However, the Prime Minister did not completely rule out future consideration of

expanded operations in Syria:

... Obviously, the Assad regime is not the kind of government

that we could ever support. Obviously, the consolidation of a terrorist State

in Eastern Syria and Northern Iraq would be a catastrophe for us as well as a

calamity for the people of that benighted region. So, do we want Assad gone? Of

course we do. Do our military operations contribute to that at this time? No,

they don’t.[135]

Given that self-defence was the basis of the legal

justification for OIR Coalition operations, the widespread collapse of ISIS in

large areas raises more urgently the question of when ISIS can be considered ‘defeated’

or at least no longer representing an existential threat to Iraq raises a

number of issues. The end-state for operations against ISIS in Iraq and Syria was

unstated, and still remains open-ended. At what point will Australia consider

ISIS ‘defeated’, or at least to no longer represent an existential threat to

Iraq, and withdraw its military forces? If ISIS were to no longer directly

threaten Iraq, would the focus of operations change and with it, the legal

justification?

Moreover, does ongoing instability in Iraq mean that

Coalition troops will be present for years to come? Successive victories

against ISIS have changed patterns of territorial control across Syria and

Iraq, exacerbating pre-existing disputes and divisions between various groups

and increasing overall instability. These problems will become more prominent

as the fight against ISIS becomes less of a priority compared to a range of

other conflicts between states, sectarian groups and international powers—though

arguably ISIS has not been completely defeated and the same problems that enabled

the group’s dramatic re-emergence in 2014 are still present. The question

therefore becomes how willing is the Coalition to prop up or assist local

governments and entities to prevent any resurgence of ISIS or similar groups?

These are questions and issues that have not been addressed by

the Australian Government or any other OIR Coalition partner to date, even

though they are an integral part of addressing the ISIS problem.

Bipartisan—mostly

The Australian Labor Party has consistently underscored its support for

the war against ISIS, and its bipartisan approach to most matters of defence

and security, which included support for the Abbott Government’s expansion of air

strikes into Syria.[136]

But while quick to support the Abbott Government’s expansion of operations into

Syria, Opposition Leader Bill Shorten noted in Parliament on 9 September 2015 that

Labor’s support was not unconditional, but subject to the following conditions:

1. ADF

operations in Syria must be constrained by the proposed legal basis of Iraq’s

collective self-defence. We call on the Government to confirm that any

Australian use of force will be limited to that necessary to halt or prevent

cross border attacks on Iraq or to defend Australian personnel, be proportionate

to that threat, and be subject to international law.

2. The Government must provide

assurance that an effective combat search and rescue capability will be in place

to meet the risks evident for any RAAF personnel downed in hostile territory. This

assurance should precede any ADF operations in Syrian airspace.

3. The Government’s overall approach

must include a substantial commitment to address the deepening humanitarian crisis

in the Middle East, and in Syria in particular. Labor welcomes

the Government’s announcement of an additional 12 000 humanitarian refugee places

to assist people affected by the crisis in Syria. Labor also welcomes

the announcement of $44 million in additional humanitarian relief funding for the

crisis in Syria, but we call on the Government to match Labor’s

proposal of $100 million in additional funding given the enormous need.

4. The Government

must formally notify the United Nations Security Council about Australia’s decision,

including our assessment of the legal basis for action, and advocate strongly for

the UN to renew efforts around a long-term, multilateral strategy to resolve

the Syrian conflict.

5. The Government

must outline to Parliament their long term strategy regarding Australia’s changing

role in the defence of Iraq and allow for appropriate parliamentary discussion -

consistent with the Government’s prior commitment to keep Parliament updated on

national security matters.[137]

Former Shadow Foreign Minister Tanya Plibersek also called on the Prime

Minister to address Parliament, outline Australia’s long-term strategy in Iraq

and Syria and allow for appropriate parliamentary discussion, highlighting that

‘our role militarily must be matched by renewed efforts toward a long-term,

multilateral strategy to resolve the Syrian conflict’.[138] In a 9 September 2015 speech

to the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, she highlighted that a bipartisan

approach requires a level of cooperation and information-sharing between

parties, and pointed out that ‘if the Government is genuinely looking for

bipartisanship on important and complex matters it might in future consider

putting more effort into working cooperatively with our Shadow Ministers’.[139]

However, the Opposition was consistently careful to note that it was

not questioning the Government’s prerogative powers, or Labor’s support for the

deployment or its legal basis, and underscored its bipartisan approach to the

issue and its acceptance of the Government’s legal justification for the

expansion of operations.[140]

Foreign policy scholars have noted, as did Labor in 2015, that while this

bipartisan approach has clear benefits, immediate and largely unconditional bipartisan

support on defence and foreign policy issues can limit the level of debate,

discussion and publicly available information on these issues.[141] On 9 September 2015, Australian Greens senator Scott

Ludlam forced a vote in the Senate in an effort to debate the war and make the Government

provide more information about its reasoning and long-term strategy.[142] The motion was voted down 37-10,

with only the Greens and Senator Jacqui Lambie voting in favour.[143] There

has been no other parliamentary debate on Iraq or Syria since, and Labor’s

initial calls for debate and discussion have not been reiterated. As such, with

the two major parties in agreement on the issue of ADF deployments, there has

been little need for the Government to explain its plans or reasoning.[144]

The decision to extend operations into Syria without parliamentary

consultation, debate or voting contrasts with the extent of debate and

discussion over these issues—including Syria specifically—in similar

parliamentary democracies such as the UK and Canada. France’s parliament also

debated the merits of military operations in Syria, an opportunity the French

Government used to explain its reasoning and approach.[145]

|

War powers

In Australia, the government of the day is not required to consult the Parliament before declaring war or deploying military forces overseas. Under Australian law this is the government’s prerogative as it is an executive power of the Commonwealth under section 61 of the Australian Constitution.

In the UK, Canada and New Zealand, the government of the day similarly does not have to seek approval from parliament before deploying troops. However, in the UK and New Zealand, conventions have developed that see such matters generally debated in parliament. In Canada, if the parliament is not already in session, then it is summoned when such a decision is made. In the US and some European countries, the parliament’s consent must be obtained to send troops overseas, or the parliament is at least notified of such action.

For more detail see: D McKeown and R Jordan, Parliamentary involvement in declaring war and deploying forces overseas, Background note, Parliamentary Library, Canberra, 22 March 2010.

|

Since the 2016 federal election, the Labor leadership has not commented

in any substantial way on broader government strategy or requested a debate on

military operations in Syria or the situation more broadly; a possible indication

there is no substantial or developed policy on the matter. The key exception

was Shadow Foreign Minister Penny Wong’s comments following the April 2017 US

strike on Syria in retaliation for the Khan Sheikhoun chemical weapons attack

in Idlib. Senator Wong expressed support for the US strike, reiterating the

Labor Party’s solidarity with the Government’s handling of operations targeting

ISIS. She also called on all sides of the conflict to ‘move towards a peaceful

solution to end the suffering of the Syrian people’ and to ‘hold the Assad

Regime to account for the crimes it has committed against its people’.[146] However,

these comments did not allude to, or appear to constitute part of any specific

policy on the region.

Conclusion

The conflict in Syria and Iraq is at a significant turning

point as the Iraqi Government claims victory over ISIS within its borders and

the Syrian Government strengthens its control over areas previously held by the

terrorist group. But with the conflict against ISIS receding (at least for

now), pre-existing disputes and divisions between groups in Syria and Iraq are

once again coming to the fore, exacerbated by the changes in territorial

control and the rise of various groups that are challenging the pre-ISIS status

quo. This raises a number of questions around strategy, future intent and the

longevity of any solution for the region. Arguably, ISIS is a symptom of

underlying, systemic issues and a problem that can only be solved by addressing

these other issues. ISIS’s defeat was a necessary operational goal, but it

leaves wider strategic issues unresolved. As such, the threat from ISIS or

potential follow-on entities will not be comprehensively defeated without

addressing the broader economic, social and political problems that exist

across the Middle East, especially while the increasing securitisation of the

problem exacerbates the marginalisation and repression at the root of these issues.

As a tool that can be applied to fix these systemic issues,

and mitigate the problems that feed into these strategic conflicts, ongoing

reconstruction assistance is more necessary than ever to address local

grievances and prevent the loss of hard-won gains in both Iraq and Syria, although

there seems to be little appetite among OIR Coalition members for the careful

consideration or application of this measure. The lack of consensus on the

lessons learnt from the expensive and ultimately less-than-successful

endeavours in Iraq and Afghanistan in past decades also adds to the reluctance

to go down this path. But pursuing various short-term operational goals in the

absence of a clear strategic end-state is also unlikely to be successful.

The US has not been forthcoming with any specific long-term

plans for its activities in Syria and Iraq, beyond emphasising that

stabilisation is a priority and that it will not engage in any form of nation-building.[147]

This is particularly pertinent in Syria where there is an understandable

reluctance to own any part of the problem post-ISIS.[148]

In an interview alongside US Defense Secretary James Mattis and Chairman of the

Joint Chiefs Joseph Dunford, the US Envoy to the OIR Coalition, Brett McGurk,

explained the ‘stablisation’ approach the administration is taking:

Stabilization is not

nation-building. We’re not attempting to dictate political outcomes nor is it

long-term reconstruction where projects are chosen by outsiders often with no

connection to the local community costing and often wasting billions of

dollars. Instead, stabilization is a low-cost, sustainable, citizen-driven

effort to identify the key projects that are essential to returning people to

their homes such as water pumps, electricity nodes, grain silos, and local

security structures, local police.[149]

However, the concern here is

that this approach does not solve the issues that created and sustained ISIS.[150] And while trying to avoid

further entanglement, the US also appears to be digging deeper into the Syrian

conflict through its ongoing cooperation with opposition groups on the ground. The

US now has military infrastructure in Syria, and continues to provide critical

support (including weapons) to the Kurds, who arguably would face significant problems

without an ongoing US presence.[151]

As such, US actions do not appear to reflect any form of transient short-term

commitment, or one that will end when ISIS is dislodged from its last urban

strongholds. The US has recognised this to a point—US Defense Secretary Mattis

noted in May 2017 that some form of stability would be required in Syria before

any US withdrawal, but this ignores the challenges to be overcome in order to

achieve stability in the first place.[152]

As a junior Coalition partner Australia will never drive the

overall trajectory of the campaign. However, in this sense it is more critical

to have a clearly articulated set of goals to avoid being drawn into any

escalation of the conflict that may not align with broader national interests. Yet,

beyond the destruction of ISIS, the Australian Government’s future intentions

remain unclear, including in relation to key interlinked issues such as the

future role of Assad and Australian involvement in aid and reconstruction

efforts. As CDF Air Chief Marshal Mark Binskin noted in Senate Estimates in May

2017, Australia’s continued military involvement is predicated on the mission

to degrade and defeat Daesh (ISIS) while it remains a threat to Iraq:

The operations we do into

Syria are in the collective self-defence of Iraq. So, all along, the mission

has not changed since October 2014, when we went in, which was to be a part of

a coalition that was looking at degrading and ultimately defeating Daesh in Iraq

and giving the Iraqis the wherewithal to secure their borders. That mission has

not changed in that period. So if we were to change that mission, it would

require us to go to government and government to provide a whole new

consideration of what we may or may not do.[153]

As such, the question of Australia’s continued involvement

in a conflict after ISIS is ‘defeated’, or at least no longer represents an

existential threat to the Iraqi Government, is also a pertinent one given that

it is the basis for the justification of Australian operations in Syria. So, if

the mission changes, the framing and extent of Australia’s participation in any

future operations may need to be revisited. But to date, the possibility that

the mission may change has not been raised publicly. While the Government’s

objective in Syria has clearly been to ‘degrade, destroy and defeat’ ISIS,

there has been no serious public discussion or parliamentary debate about what

comes next. Neither the Government nor the Opposition has outlined any current plan,