22

September 2016

PDF Version [2808KB]

Wendy Bruere and Cameron Hill (with the assistance of Stephen

Fallon)

Foreign Affairs, Defence and Security Section

Executive summary

- Since the election of the Coalition Government in September 2013,

funding reductions as well as administrative and policy changes have been made

to Australia’s overseas aid program. This paper outlines the key changes under the

Abbott and Turnbull governments from September 2013 to June 2016.

- Successive and very large funding cuts and the decision by both

major parties to eschew a timetable for the goal of Official Development

Assistance (ODA) expenditure reaching 0.5 per cent of Gross National Income (GNI)

have been explained as a response to worsening fiscal circumstances. This marks

a pronounced shift away from the trend of previous years, which saw bipartisan

support for significant increases to ODA.

- The merger of the former Australian Agency for International

Development (AusAID) with the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT)

aligns aid more closely with Australia’s foreign and trade policy objectives,

while potentially diminishing the relative weight accorded to poverty reduction

and sustainable development in considerations of Australia’s ‘national

interests’.

- Both the Abbott and Turnbull governments emphasised the aid

program’s strengthened focus on the Indo-Pacific region. Nevertheless, as part

of the wider funding cuts, aid to most countries in East Asia and South and

West Asia has been reduced since 2013. Australian aid to Africa and the Middle

East has been significantly reduced and aid to the Caribbean and Latin America is

being phased out completely. While aid to Papua New Guinea has increased, aid to

the other Pacific Island countries has been subject to smaller funding

reductions. Many global programs have also had their funding reduced.

-

A new monitoring and evaluation framework attempts to link

funding more closely to performance. This has been accompanied by an increased

emphasis on aid-for-trade and gender equality as sectoral priorities.

- Climate change has been an area of significant readjustment, with

references to global warming all but disappearing from key aid policy documents

during the Abbott Government. Climate change re-emerged as an important area of

assistance, with the Turnbull Government funding commitments at the 2015 Paris climate

change summit.

- The 44th Parliament demonstrated a continued interest

in aid and international development issues. Several parliamentary inquiries

examined various aspects of the aid program and alternative policies were announced

by the Labor Opposition and other non-government parties ahead of the 2016

federal election.

Contents

Executive

summary

Introduction

Background: aid program funding and

expenditure 2005–2013

Funding cuts to the aid program

2013–14 to 2016–17

The Coalition’s 2013 election

platform

2014–15 Budget

Funding cuts

Geographic priorities

Other changes

2015–16 and 2016–17 Budgets

2015–16 Budget

2016–17 Budget

2016 federal election campaign

Changes to aid management and policy

directions

Integration of AusAID and DFAT

Aid and the ‘national

interest’

Aid-for-trade and private sector

development

The new performance framework:

changes to monitoring and evaluation

The Indo-Pacific and increased

consolidation

Addressing gender inequality

Climate change

The 44th Parliament and Australia’s

overseas aid program

Parliamentary Committee inquiries

‘Australia’s overseas aid and

development assistance program’, SFADT References Committee, 2014

‘The role of the private sector in

promoting economic growth and reducing poverty in the Indo-Pacific’, JSCFADT,

2015

‘The human rights issues confronting

woman and girls in the Indian Ocean–Asia Pacific region’, JSCFADT, 2015

‘The delivery and effectiveness of

Australia’s bilateral aid program in Papua New Guinea’, SFADT References

Committee, 2016

Alternative policies

Labor Opposition

Other parties

Conclusion

Introduction

The Coalition Abbott

Government made important changes to Australia’s Official Development

Assistance (ODA) programs following its election in September 2013.

Large reductions in funding,

foreshadowed in the Coalition’s September 2013 pre-election costings, commenced

in January 2014. A further series of funding cuts were announced in the December

2014 Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO) and implemented in the

2015–16 Budget. While non-government organisations (NGOs) and some independent experts

strongly criticised the severity of these cuts, they continued to be

implemented as part of the Turnbull Government’s 2016–17 Budget ahead of the dissolution

of the 44th Parliament.

Alongside the reductions in

funding, the Coalition Government has changed the way Australia’s aid program

is administered, and has adjusted sectoral priorities. These changes include:

- the merger of the former Australian Agency for International

Development (AusAID) with the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT)

- a more explicit focus on using aid to pursue foreign and trade

policy goals

- an increased focus on aid-for-trade

- changes to monitoring and evaluation

- a higher proportion of aid funding directed to the Indo-Pacific

region and

- a commitment to strengthen the focus on addressing gender

inequality and, after some adjustment, the causes and impacts of climate change

through aid.

Some of these changes, such as the

merger of AusAID and DFAT and the increased emphasis on the national interest

and aid-for-trade, have been criticised by some NGOs and other experts. Others,

such as an increased focus on addressing gender inequality and adjustments to funding

for climate change, have been welcomed. But they have also raised new questions

about how these issues will be incorporated effectively into existing programs,

how outcomes will be measured and how new activities will be funded.

The government heralded its changes

as part of a ‘new aid paradigm’.[1]

Some commentators supported this view, welcoming the changes as ‘arguably, the

most significant structural reform in our aid history’.[2]

Others, however, have suggested that the changes pursued by the Coalition

Government since 2013 represent little more than a ‘rebranding’ or a process of

‘incremental change’, rather than a fundamental shift in approach.[3]

The 44th Parliament

continued to take a strong interest in aid and development issues during its

term. The Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade (SFADT) References

Committee conducted inquiries into ‘Australia’s overseas aid and development

assistance program’ (2014) and ‘the delivery and effectiveness of Australia’s

bilateral aid program in Papua New Guinea’ (2016). The Joint Standing Committee

on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade (JSCFADT) conducted inquiries into ‘the

role of the private sector in promoting economic growth and reducing poverty in

the Indo-Pacific region’ (2015) and ‘the human rights issues confronting women

and girls in the Indian Ocean–Asia Pacific region’ (2015).

This paper

outlines the key changes to the aid program during the Abbott and Turnbull Coalition

governments during the period from September 2013 to May 2016, and examines the

responses from NGOs and other experts. It also briefly discusses the findings

and recommendations from parliamentary committee inquiries conducted during the

44th Parliament, as well as alternative policies put forward by the Labor

Opposition and non-government parties over this period.

Background:

aid program funding and expenditure 2005–2013

During the

period 2005 to 2013 Australia’s ODA expenditure steadily increased, both as a share

of Gross National Income (GNI) and in absolute dollar terms. While Australia’s agreement

to the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in 2001 is sometimes viewed as the

point at which Australia committed to increase ODA as a percentage of GNI, Tim

Costello, the then CEO of World Vision Australia, explained that this was not

the case:

Australia

agreed, along with all other UN [United Nations] members, to adopt the MDGs in

2001. Goal 8 sets 0.7% of GNI as the benchmark level of development assistance

that developed countries should commit to. However, the Howard Government

insisted that both the 0.7% target and the use of the MDGs as a measure of aid

effectiveness were only aspirational. Hence it was not until 2007 that

Australia agreed to use the MDGs as a benchmark in measuring the effectiveness

of its own aid program.[4]

Prior to

this, Prime Minister John Howard had pledged at a 2005 UN conference that his government

would double the size of Australia’s aid program by 2010, from $2 billion to $4

billion annually.[5]

This commitment was preceded by Australia’s historic $1 billion aid package to

assist Indonesia’s reconstruction and development after the 2004 Indian Ocean

tsunami.[6]

The Howard Government’s last aid budget statement, delivered in May 2007, included

major new initiatives to assist Australia’s developing country partners to deliver

better education and health services ($1.1 billion over four years), improve

infrastructure ($500 million over four years), and address environmental and climate

change challenges ($196 million over five years).[7]

During the subsequent

2007 election campaign, the Labor Party committed to reaching 0.5 per cent of

GNI in foreign aid by 2015–16 and this target gained bipartisan support.[8]

The Sydney Morning Herald reported that ‘aid sector insiders say it is

the first time in memory that overseas aid has received so much attention

during an election campaign’.[9]

The 2008‒09 Budget reflected the Rudd Government’s 2007 commitment, stating

that ‘in 2008‒09 AusAID will commence implementation of the Government’s

long-term commitment to increase Australia’s official development assistance

(ODA) to 0.5 per cent of GNI by 2015‒16’.[10]

The 0.5 per

cent target was reaffirmed by both parties during the 2010 election campaign. Opposition

foreign affairs spokesperson, Julie Bishop, stated that if the Coalition were elected

it would ‘honour our commitment to deliver 0.5 per cent by 2015’.[11]

Despite the reaffirmation of the target in a 2011 review of the aid program, the

commitment was delayed by one year in the Gillard Labor Government’s

2012‒13 Budget. It was again delayed (to 2017‒18) in the 2013–14

Budget.[12]

In this last budget statement, the Gillard Government committed to total ODA

expenditure estimated at $5.66 billion, or 0.37 per cent of GNI.[13]

Funding cuts

to the aid program 2013–14 to 2016–17

The Coalition’s

2013 election platform

With the

election of the Coalition Government in September 2013, a timetable for achieving

the 0.5 per cent target was abandoned altogether and aid funding was

significantly reduced from previous levels. The Coalition’s final pre-election costings

document, published just prior to the 2013 federal election, stated:

It is unsustainable to continue massive projected growth in

foreign aid funding whilst the Australian economy continues at below trend

growth. Australia needs a stronger economy today so that it can be more

generous in the future. The Coalition will cut the growth in foreign aid. We

will index the increase to the Consumer Price Index. Reductions in projected

aid spending of $4.5 billion will be allocated to other Coalition policy

priorities, including productive infrastructure such as Melbourne’s East West

link ($1.5 billion), Sydney’s WestConnex ($1.5 billion) and the Brisbane

Gateway Motorway upgrade ($1 billion).

The Coalition remains committed to the Millennium Development

Goal of increasing foreign aid to 0.5 per cent of GNI over time, but cannot

commit to a date given the current state of the federal budget after six years

of Labor debt and deficit. As well, the Coalition will re-prioritise foreign

aid allocations towards Non-Government Organisations that deliver on-the-ground

support for those most in need.[14]

After

assuming office in September 2013, the Coalition Government announced in

January 2014 that it would cut $656 million—or almost 12 per cent—from the

2013‒14 aid budget.[15]

2014–15

Budget

Funding cuts

In the

2014–15 Budget, the total ODA expenditure estimate was $5.032

billion, with Foreign Minister Julie Bishop explaining that the budget would be

‘stabilised at $5 billion in 2015‒16, thereafter

increasing annually by CPI [the Consumer Price Index]’.[16] The impact of

this decision was described at the time by the Parliamentary Library—‘in

effect, the Government expects to “save” $7.7 billion over five years by

maintaining ODA at its 2013–14 level of $5 billion in 2014‒15 and 2015‒16 before it starts to grow in line

with CPI from 2016‒17’.[17]

Despite the commitment to ‘stabilise’ funding and to

increase aid spending in line with inflation, the subsequent December 2014 MYEFO contained additional cuts to the aid budget. These cuts amounted to $3.7 billion over the forward estimates.[18] Stephen Howes and Jonathan Pryke of the Development Policy Centre at

the Australian National University (ANU) described the 2014 MYEFO reductions as

the ‘biggest aid cuts ever’ and ‘completely unprecedented’.[19] They explained

that ‘after inflation the cuts, which

continue to 2016‒17, are 28% relative to this year. In 2016‒17, aid

will be 33% less than it was relative to the Labor’s [sic] final year of

aid spending, that is, 2012‒13’.[20]

They also detailed how this compared to previous funding cuts:

...most of the cuts

will be implemented next year (2015‒16), when the aid program will fall by

around $1 billion or 20%. This will be the biggest single-year change ever to

the aid program (up or down), more than three times as big as the next largest

cut ($323 million in 2012‒13 prices; back in 1986‒87).

It is also the largest percentage change (up or down), and almost twice as

large as the next largest cut (–12%, again 1986‒87).[21]

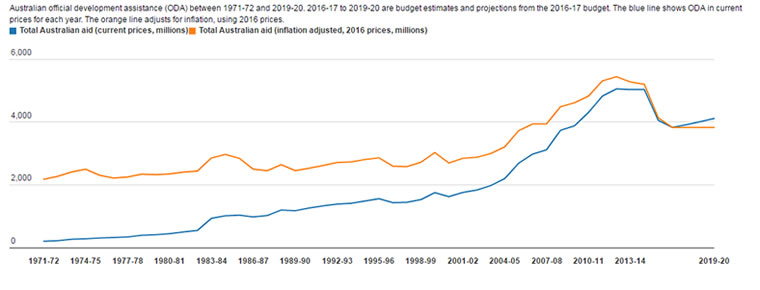

In terms of the

trends in aid funding, under the scheduled reductions, ODA expenditure has

fallen from a high of $5.4 billion in 2012–13 to an estimated $3.8 billion in

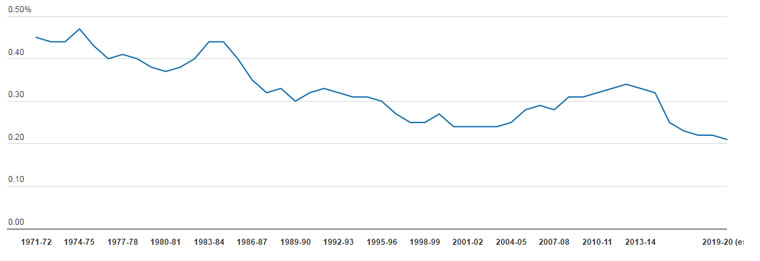

2016–17 (see Figure 1). According to projections by the Development Policy Centre,

in proportional terms the cuts will see Australian aid falling further to a

record low of 0.21 per cent of GNI by 2019‒20 (see Figure 2).

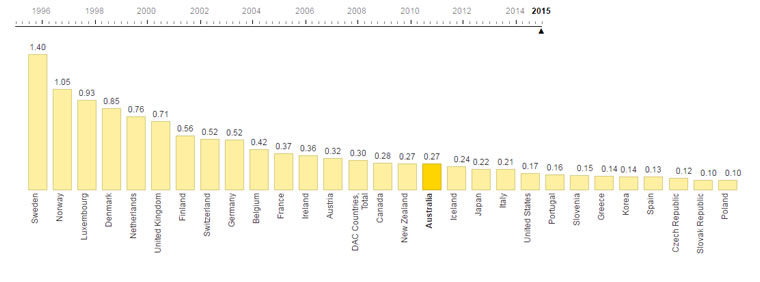

In

comparative terms, over this same period (2012–13 to 2019–2020) Australia is forecast

to drop from 13 to 19th place in the ODA/GNI rankings of the Organisation for

Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) 28 bilateral donors, assuming other

donors maintain current levels of aid.[22]

In 2015, Australia ranked 16th on the ODA/GNI comparison (see Figure

3).

According

to the Lowy Institute, the funding cuts put Australia:

...at odds with the aid budget trajectories that many other

OECD countries are following. In 2013, the Conservative government in the UK

became the first G7 donor to reach the OECD’s 0.7% of GNI target, increasing

its official development assistance (ODA) by 27.8% on 2012 levels. It has since

passed a bill enshrining the 0.7% commitment into law.[23]

Figure 1: ODA expenditure, 1971–72 to 2019–2020 (est.)

Source: Development Policy Centre,

Australian aid tracker: trends

Figure 2: ODA as a percentage of GNI, 1971–72 to 2019–20

(est.)

Source: Development Policy Centre, Australian aid tracker: trends

Figure 3: ODA as a percentage of GNI for members of

the OECD Development Assistance Committee, 2015

Source: Development Policy Centre, Australian aid tracker: comparisons

Unsurprisingly,

some aid organisations and analysts criticised the cuts on the basis of their

potential impact on the world’s poor. UNICEF Australia claimed that Australia was

set to ‘become one of the world’s least generous donors’, while Care Australia

asserted that the cuts would put poverty reduction gains in the region at risk.[24]

In addition

to decreasing available funds, aid organisations also pointed out that the cuts

combined with other changes to the aid program meant that funding would become

less predictable and that this would reduce the effectiveness of Australia’s

aid by undermining long-term planning. Oxfam Australia stated in its submission

to the 2014 Senate inquiry into ‘Australia’s overseas aid and development assistance

program’:

...the

implementation of aid cuts, the reduction in the future aid budget and the

integration of AusAID and DFAT ... have generated significant uncertainty within

DFAT, NGOs, beneficiaries and partners on the ground with particular disquiet

around the predictability of funding.

Yet

predictability is one of the fundamental aid effectiveness principles to which

Australia has committed. Aid programs generally require a multi-year commitment

to enable proper planning, implementation, impact and evaluation. A lack of

certainty as to the continuity of funding is detrimental to aid programming and

may undermine the benefits already achieved.[25]

This view was

also reflected in the Australian Council for International Development’s (ACFID)

submission, which argued that aid funding is considerably less effective when

it is highly variable and unpredictable from year to year.[26]

Geographic priorities

The 2014‒15

Budget was an opportunity for the Coalition Government to further detail which

regions and countries would be subject to reductions in funding. The geographic

areas that experienced the most significant cuts in proportional terms were

Africa and the Middle East and Latin America and the Caribbean.

While in

Opposition, the Coalition had claimed that increases in aid to Africa, Latin

America and the Caribbean prior to Australia winning a UN Security Council seat

in late 2012, were linked to the Labor Government seeking support for the bid

from countries in these regions.[27]

Using this justification, the Coalition asserted that the cuts could be seen as

returning aid spending in these areas to pre-bid levels.[28]

ODA to sub-Saharan

Africa was reduced from $355.1 million in 2013‒14 to $186.9 million

in 2014‒15. In the case of the Middle East and North Africa (excluding

the Palestinian Territories), the budget estimate over the same period was

reduced from $46.8 million in 2013–14 to $8.8 million in 2015–16.[29]

In Latin

America and the Caribbean, programs were scheduled to be phased out

completely and the 2014‒15 budget estimates for the two regions were

$16.1 million and $5 million respectively, down from $24.8 million and $13.3

million in the 2013‒14 budget estimates.[30]

As the

Development Policy Centre noted at the time, one of the few winners was Papua

New Guinea (PNG), which received an increase in ODA from the 2013‒14 budget

estimate of $507.2 million to an estimated $577.1 million in the 2014‒15 Budget.[31]

The increased aid to PNG—and a commitment to spend 50 per cent of this aid on

infrastructure projects—was a continuation of the existing Regional

Resettlement Arrangement, an agreement made with PNG under the Rudd Labor

Government in June 2013.[32]

This was despite the Coalition Opposition’s previous criticism of the agreement

in the months leading up to the 2013 election, when it argued that the Rudd Government

had ‘subcontracted out to PNG the management of our aid program’.[33]

Other changes

Two other key

changes in the 2014‒15 Budget were the restoration of humanitarian and

emergency funding, which had been cut in January 2014, and the cessation of the

previous government’s use of funds from the aid budget to meet onshore asylum

seeker subsistence costs.

In January 2014, the

allocation for Humanitarian, Emergencies and Refugee programs was cut to

$264.2 million, down from a 2013–14 budget estimate of $383.9 million. This was

increased to $338.6 million in the 2014–15 Budget.[34]

A significant portion of these funds has been provided to the international

response to the ongoing humanitarian crisis in Syria, to which successive Australian

governments have committed over $430 million since 2011.[35]

While the

reversal of the Labor Government’s decision to allocate some $375 million from

the aid budget to meet onshore asylum seeker costs was welcomed by

organisations such as ACFID, some criticism was made of the aforementioned

increase in ODA to countries cooperating with Australia on asylum seeker

policies.[36]

In an article deeply critical of the government’s aid policies, Thulsi

Narayanasamy, the director of the aid monitoring NGO, AID/WATCH, suggested that

the aid increase for PNG agreed by Labor and continued by the incoming

Coalition Government was a ‘bargaining chip’ for Australia’s detention centre

on Manus Island.[37]

Similar criticisms were levelled following the government’s decision to increase

aid to Cambodia by $40 million over four years as part of a refugee

resettlement agreement announced in October 2014.[38]

2015–16 and

2016–17 Budgets

2015–16 Budget

In accordance with the schedule of cuts outlined in the December

2014 MYEFO, the 2015–16 Budget saw the biggest single reduction in annual aid

by any Australian government. Total ODA dropped by around 20 per cent, or almost

$1 billion, decreasing from an expenditure outcome of $5.031 billion in 2014–15

to budgeted expenditure of $4.051 billion in 2015–16.[39]

In terms of the impact on country and regional programs, the

Development Policy Centre observed at the time:

The regions that were worst hit, not surprisingly, were those

deemed outside of Australia’s traditional areas of interest, now defined as the

Indo–Pacific region. Sub-Saharan Africa saw its budget cut by 70

percent. Aid to the Middle East, including the Palestinian Territories,

declined by 43 percent.

The Pacific and PNG have been spared for the most

part. Indeed, DFAT country allocations remain constant in nominal terms in all

Pacific island countries, even in the North Pacific, which has not

traditionally been a priority for Australia. Aid to Papua New Guinea has

declined, but only marginally, by 5 percent. Funding for regional programs in

the Pacific will be 10 percent lower in 2015-16.

The government has adopted an across the board 40 percent cut

in other regions in order to meet the $1 billion of cuts to the aid budget. In East

Asia, all but two countries suffered a cut to aid of 40 percent. Indonesia

fared no worse than the Philippines or Mongolia, despite recent commentary

suggesting that larger cuts were a possibility. Timor Leste was protected with

a 5 percent cut. Aid to Cambodia will remain constant in nominal terms—the only

country in East Asia where this is the case. Aid for regional initiatives was

similarly cut by 40 percent.

The same approach was applied in South and West Asia,

where all but one country saw a 40 percent decline in aid from Australia. That

one country, Nepal, will receive the same level of funding as in 2014-15. The

40 percent cut was applied to regional initiatives in South Asia, just as in

East Asia.[40]

(emphasis added)

Indonesia, which suffered one of the largest cuts in terms

of Australia’s East Asia aid programs, appeared unconcerned, at least publicly,

with a government spokesman stating in May 2015:

‘Indonesia at the moment is no longer a country that needs

aid for development’, he said. ‘Nevertheless, any aid given by Australia is

their effort to increase, to strengthen our partnership. And so, it’s their

right to give, but Indonesia is not asking’.[41]

In terms of global programs, while NGO programs, humanitarian

aid and multilateral development banks were largely spared from large cuts, funding

for UN agencies (with the exception of UN Women) and volunteer programs was subject

to significant reductions.[42]

The magnitude of the cuts was

confirmed by figures released subsequently by the OECD which showed that

Portugal and Australia were the two members of its Development Assistance

Committee which oversaw the largest declines in ODA in 2015.[43]

2016–17

Budget

As part of the December 2014 MYEFO, over $220 million worth

of cuts to the aid program were scheduled for the 2016–17 Budget. Despite

calls from NGOs in the lead-up to the Budget for these to be reversed, the cuts

proceeded.[44]

The 2016–17 country and regional allocations reinforced

those set in 2015–16. Total estimated ODA to PNG and the Pacific was

increased slightly, from $1.119 billion in 2015–16 to $1.138 billion in

2016–17. Total estimated ODA to South East and East Asia (down from

$909.5 million to $887.7 million), South and West Asia ($310.4 million

to $282.8 million), Africa and the Middle East ($185.8 million to $184.9

million) and Latin America and the Caribbean ($13.4 million to $11.0

million) was largely stabilised in the wake of the large cuts in 2015–16.[45]

Global programs bore the brunt of the 2016–17 cuts,

decreasing from $334 million to an estimated $199 million as a result of

delayed payments to some international health funds.[46]

The need to honour these commitments in future years is likely to limit any

future growth in country programs. Other pending decisions, such as whether

future contributions to the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank will

come from the existing ODA budget, will also constrain future country program growth.[47]

No further cuts over the forward estimates were announced in

the 2016–17 Budget which provides for aid to increase in line with inflation

over the forward estimates.[48]

2016

federal election campaign

In the penultimate week of the 2016 federal election

campaign, the government released its foreign policy statement, The

Coalition’s Policy for a Safe and Prosperous Australia. The statement flagged

two new aid initiatives. The first is a commitment to invest $100 million over

five years in a new ‘regional health security partnerships fund’ that will

‘harness Australia’s world leading research institutions, scientific expertise,

innovators and entrepreneurs to improve health outcomes in our part of the

world’.[49]

The second initiative is a mentoring program that will connect ‘female leaders

in Australia with emerging women leaders in our region’.[50]

This latter program is estimated to cost $5.4 million over five years. Both

initiatives would be funded out of the aid budget.[51]

Changes to aid management and policy directions

Integration

of AusAID and DFAT

In addition

to the funding cuts, one of the first and most dramatic changes the Abbott Government

made to the management of the aid program was the abolition of AusAID and the integration

of the agency’s aid management function into DFAT. This change was announced soon

after the election of the Coalition in September 2013 and the merger commenced in

November 2013. This change had not been foreshadowed

prior to the election, nor had it been identified as an individual savings

measure in the Coalition’s pre-election costings.[52]

One of the most immediate impacts of the decision was that the candidates

selected for AusAID’s 2014 graduate program had their offers withdrawn,

prompting some to initiate legal action against DFAT.[53]

In a 1

November 2013 media release, the Foreign Minister, Julie Bishop, argued that the

merger would result in:

...the alignment of Australia’s foreign, trade and

development policies and programs in a coherent, effective and efficient way ...

It will promote Australia’s national interests, through contributing to

international economic growth and poverty reduction, and support Australia’s

foreign and trade policy. [54]

The minister

went on to emphasise that integration of AusAID and DFAT would ‘strengthen

economic diplomacy as the centre of Australia’s international engagement’.[55]

While Australia’s aid agency had been through a number of changes in the past

40 years, including being part of the wider foreign affairs portfolio from 1977

to 2010, it consistently had a separate identity and a direct

reporting relationship with its ministers from late 1974 until the 2013 change.[56]

The merger followed similar changes undertaken by

conservative governments in Canada and New Zealand.[57]

Acknowledging the significant challenges associated with the merger, the

Secretary of DFAT, Peter Varghese, observed early in the process that ‘we are

bringing together two moving and shrinking parts, and that’s going to be a

very, very complicated process’.[58]

He also noted that ‘there has to be a general acceptance that we’re going

through this integration process but that the spine of our organisational

structure is going to rest with the DFAT organisational structure’.[59]

PNG, one of Australia’s largest aid recipients, ‘enthusiastically’

welcomed the merger.[60]

The country’s Prime Minister, Peter O’Neil, stated that it would allow Australia’s

development assistance to be better aligned with PNG’s priorities.[61]

Noting the muted reaction on the part of Australia’s other key development

partners, one commentator surmised that ‘capitals such as Jakarta and Hanoi

will view the change as Australia’s business’.[62]

Although some NGOs acknowledged the potential benefits of the merger,

many also raised concerns about how the change might negatively impact development

effectiveness, including through the loss of experienced staff. World Vision

described the merger as a ‘backward step’ and its then CEO, Tim Costello, said

it would ‘detract from the fundamental purpose of foreign aid—which is to

alleviate poverty overseas’.[63]

ACFID also

questioned whether the merger would reduce the effectiveness of aid delivery,

noting in a February 2014 submission to the 2014 Senate reference committee’s inquiry

that the new structure was at odds with international practice, and that the ‘delivery

and assessment of a large aid program is obviously not the traditional activity

of a foreign ministry’.[64]

Care

Australia, in its submission to the same inquiry, argued that despite some potential

benefits—including a ‘consistent Government position on aid and development’, ‘the

potential for a much stronger diplomatic effort on key development issues’ and ‘greater

integration across government in areas which have both domestic and

international implications such as pandemic disease’—there was still a need for

the aid program to have a distinct identity within the portfolio.[65]

Some of the risks of the merger raised by Care Australia included:

...uncertainty

about policy priorities and budgets are disrupting program delivery and could

undermine effectiveness; loss of experienced aid staff could weaken program quality

and performance oversight; short term imperatives could over-ride long-term

issues of effectiveness and sustainability; and foreign policy objectives may

distort effective aid spending.[66]

Save the

Children agreed that ‘aid should be aligned with our national interest’, but

emphasised that ‘the concept of national interest must be interpreted more

broadly than Australia’s immediate foreign affairs and trade objectives’.[67]

It argued that a key benefit of AusAID’s status as an executive agency—that is,

being administratively separate, but with a direct reporting responsibility to

a minister—was that it ‘had a distinct humanitarian identity, housed a

dedicated body of expertise on aid and development policy and programs, was one

step removed from short-term political objectives, and was a highly visible

demonstration of Australia’s commitment to international development’.[68]

As part of

concerns over how the merger might detract from aid effectiveness in the

long-term, Oxfam Australia noted the need to retain appropriate aid expertise,

referring to the experience of the New Zealand Government, which ‘found that

retaining development specialists was key to an effective aid program when it

merged aid into foreign affairs and trade’.[69]

Oxfam’s submission to the inquiry emphasised that ‘it is essential that

expertise and institutional learning in the complex area of international

development be maintained and that the development of skills be encouraged’.[70]

While Oxfam

Australia acknowledged that the merger offered ‘opportunities to strengthen

Australia’s contribution to international development by better aligning

foreign affairs, trade and aid’ and ‘opportunities to better integrate

Australia’s poverty reduction aims into its trade negotiations, with potentially

significant benefits for developing countries’, it also emphasised that ‘the aid

program must be given appropriate focus and priority within DFAT.[71]

The impact

of losing experienced staff was also raised by ACFID, which pointed to a 2012

Australian Aid Stakeholder Survey by the Development Policy Centre that had

already ‘identified high staff turnover as the most serious weakness in the

effectiveness of Australia’s aid program. It was found to undermine the

consistency of effort, and the accumulation of expertise, required to deliver

effective aid’.[72]

As anticipated,

after the merger, a significant number of former AusAID staff was not retained.

In evidence to Senate Estimates hearings in early 2015, DFAT Secretary Peter Varghese

stated that of the 500 positions abolished as a result of the merger, 374

redundancies had been offered. Former AusAID staff were disproportionately

represented with 221, compared to 153 pre-merger DFAT staff.[73]

Given that prior to integration, DFAT had 2,521 Australian staff

(plus 1,771 locally engaged staff) while AusAID had 1,724 Australian staff (and

651 locally engaged staff) this disparity is even more pronounced.[74]

As well as noting

the Australian staff lost through redundancies, some commentators highlighted

the risk that reduced staff satisfaction among locally engaged staff, who are often

cited as a key asset of the aid program, could lead to an attrition of skilled

workers. The Development Policy Centre warned of indications that talented local

staff in Indonesia were ‘looking for, and finding, alternative options’, a

development that ‘could compromise the quality of aid delivery and thus reduce

the claimed foreign policy dividends from the merger’.[75]

Reduced morale

among former AusAID staff at DFAT was revealed by the media in a leaked 2014 survey

of staff satisfaction, which showed former AusAID staff were less happy after

the merger, and considerably less happy than staff who had been in DFAT prior

to the merger. According to an ABC News report:

...only 33 per cent of former AusAID staff feel “part of the

team”, compared to 70 per cent of their colleagues who have always been at DFAT

... Twenty-one per cent of ex-AusAID staff surveyed indicated they would leave

the agency within the next two years, compared to 11 per cent of staff who were

at DFAT before the integration.[76]

The report

added that ‘some AusAID staff have privately described it as a “hostile

takeover” by DFAT’.[77]

A DFAT spokesperson said at the time that ‘the relatively low satisfaction

rates among former AusAID staff was [sic] not unexpected, given the

scale of the changes, and that the survey was conducted only four months into

the integration process’.[78]

Commenting in

2015 on the results of a follow-up survey, Varghese observed that while overall

morale had improved, not all the challenges of integrating AusAID into DFAT had

been overcome and that the results painted a ‘mixed picture’.[79]

He observed that DFAT’s information technology and human resource management

systems had come under ‘significant pressure’.[80]

In mid-2015, it was reported that almost 800 former AusAID staff were still

awaiting the necessary upgrades to their security clearances.[81]

Varghese also said the department could still ‘do more to embed the DFAT

values, improve transparency and ensure we are flexible and open to change’.[82]

Aid and the ‘national interest’

In

discussions of the goals and objectives of aid, the Abbott and Turnbull governments

frequently emphasised the importance of pursuing Australia’s ‘national interest’

as a key justification for the AusAID-DFAT merger.[83]

This received some criticism, including from AID/WATCH which argued that ‘Australia

is a signatory to the Paris Declaration of Aid

Effectiveness which acknowledges that aid should not be driven

by donor priorities; so aid policy shouldn’t be based on Australia’s commercial

or domestic considerations’.[84]

Indeed, as

noted, in Opposition the Coalition had decried the alleged use of the aid

program to pursue foreign policy objectives such as the UN Security Council

membership bid. In 2010, Julie Bishop (as Shadow Foreign Minister) had argued that

the Rudd Government had ‘massively increased the aid budget in the year prior

to the vote and there are growing concerns that it will be used to buy votes,

particularly in Africa and Latin America, where there are large numbers of UN

votes’.[85]

It is important to note that the Security Council bid was led by DFAT, not

AusAID. If correct, therefore, Ms Bishop’s allegation would seem to suggest a

close ‘alignment’ between Australia’s foreign policy objectives and the aid

program at the time, despite the fact that these were managed across two

separate agencies.

In fact, furthering the ‘national interest’, however

defined, has been a long-standing goal of the aid program under

successive governments, both Labor and Coalition. In its 2006 white paper on

Australian aid, the Howard Government stated that the official objective of the

Australian aid program was ‘to assist developing countries to reduce poverty

and achieve sustainable development, in line with Australia’s national interest’.[86] The Labor

Government’s 2012 aid policy, An Effective Aid Program for Australia: Making

a Real Difference—Delivering Real Results, stated ‘The fundamental purpose

of Australian aid is to help people overcome poverty. This also serves

Australia’s national interests by promoting stability and prosperity both in

our region and beyond’.[87]

Under the

Abbott and Turnbull Coalition governments, the objective of the aid program was

determined as:

...to promote Australia’s national interests by contributing

to sustainable economic growth and poverty reduction ... The Australian

Government’s aid program will promote prosperity, reduce poverty and enhance

stability with a strengthened focus on our region, the Indo-Pacific.[88]

In this context, the policy debate is less about whether or not the aid

program should be used to serve the national interest, and more about how the

‘national interest’ is defined in particular circumstances. At issue is the

weighting that is accorded to the long-term benefits of an effective aid

program that does—and, just as importantly, is seen to—reduce poverty and help

partner countries address their long-term development priorities, relative to

that accorded to more immediate foreign and trade policy considerations.

These elements of the ‘national interest’ are not necessarily mutually

exclusive. There are times, however, when the relative priority accorded to each

requires conscious choices and trade-offs. As one former AusAID senior official

observed just prior to the merger, ‘there is tension from time to time between

AusAID and DFAT in terms of how development can support foreign policy

objectives’.[89]

In the absence of a dedicated institutional and intellectual body responsible

for advancing a development perspective on the national interest, these choices

and trade-offs are more likely to favour narrower, short-term objectives.

Nevertheless, while the merger of AusAID and DFAT represented a strengthening

of the weight accorded to foreign and trade policy objectives, this has been

characterised by some as less of a major policy shift and more of a symbolic change

or ‘rebranding’. Professor Stephen Howes from the Development Policy Centre takes

this view:

...all the talk of economic diplomacy and the national

interest seems to be a way to rebrand the aid program, to sell it to a

sceptical Australian audience ... if the Foreign Minister can firm up support for

aid using a different language then all strength to her.[90]

Others are less

sanguine, describing the pursuit of the AusAID–DFAT merger in order to better

align aid with foreign and trade policy objectives as ‘considerable pain for

marginal policy gain’.[91]

Aid-for-trade

and private sector development

In a speech

in April 2014, the Foreign Minister emphasised that the centrepiece of the

Coalition Government’s approach to aid would be the use of ‘aid-for-trade’ to

support economic growth and attract private sector investment in developing

countries:

In these first seven months as Foreign Minister, one of my highest

priorities in this area has been to adopt an ‘aid for trade’ policy which uses

foreign aid to connect businesses in developing countries to regional and

global supply chains. This includes provision of infrastructure, training and

business support. It also involves helping countries reform their trade and

economic policies and improve their capacity to negotiate trade agreements.

On average, each dollar invested in aid for trade initiatives increases

recipient country exports by eight dollars.

....

We will also work with our partners to identify specific market

failures, and address them through well targeted projects and programs to

create governance environments that attract international, particularly private

sector investment.[92]

The government’s

aid-for-trade policy contains a target for the aid program to lift its

expenditure in this area to least 20 per cent by 2020.[93]

A 2015 report on the performance of Australia’s aid details the changes and

progress as follows:

Over the last

nine years, the average proportion of the aid budget spent on aid for trade was

13.8 per cent. The estimated expenditure on aid for trade in 2013–14 was $675

million, equivalent to approximately 13.5 per cent of total ODA. It is

estimated that this will increase to approximately 14.7 per cent of total ODA

in 2014–15. If realised, this would demonstrate good initial progress in

meeting the 20 per cent target.[94]

Aid-for-trade

and private sector development were areas also promoted by the previous Labor government

through its support for large infrastructure and connectivity projects such as

the Cao Lanh bridge in Vietnam, the inclusion of aid components in various free

trade agreements and its 2011 announcement of a new ‘Mining for Development’

initiative.[95]

Supporters

of aid-for-trade, such as Jim Redden from the University of Adelaide’s

Institute for International Trade, have argued:

Recent research across the Asia Pacific and elsewhere

demonstrates an increasingly positive correlation between more open,

competitive trade policies and sustainable poverty reduction if certain

pre-requisites (trade openness, domestic reform & support for adjustment

costs, robust and responsible private sector, international reform and political

will) are in place.[96]

Organisations

and experts contesting the increased focus on aid-for-trade have countered that

while trade liberalisation and economic growth may be necessary conditions for

poverty reduction, they are rarely sufficient. They have pointed to the fact

that around 73 per cent of the world’s poor now live in so-called ‘middle

income’ countries, despite these countries being the ‘major engines of global

growth’.[97]

There have

also been some questions around the evidence base that underpins aid-for-trade.

In an article on The Conversation, research consultant Anna Gero argues

that the effectiveness of aid-for-trade has not actually been

clearly established, as studies to date have not properly assessed poverty reduction

impacts:

Despite the growth in aid for trade interventions globally, critics

argue that there remains a lack of data on if, how, and to what extend aid for trade interventions impact on levels of

poverty. While studies are emerging that aim to assess

the aid for trade “lessons from the ground”, most fail to provide details of local impacts of aid for trade,

instead focusing on macro-level results.

And as is the case with many evaluations, causal linkages between aid

for trade interventions and poverty are based on assumptions and are inherently

difficult to measure, posing a challenge for donors as well as NGOs that may

begin incorporating aid for trade into their programming in order to access

funds through the aid program.[98]

As well as

promoting the growth of the private sector to drive development, the concept of

aid-for-trade includes engaging the private sector in ‘the design or delivery

of investments; innovative approaches to project financing; public-private

partnerships; improving the regulatory environment for private sector

participants; or addressing other constraints to economic growth’.[99]

In an April 2014 speech, the Foreign Minister highlighted the ‘innovative approaches and different business models the private

sector can bring’ and how these can provide ‘solutions for otherwise

intractable development challenges’.[100]

In March

2015, the Foreign Minister announced the first three innovationXchange initiatives—part

of a $140 million project involving global and local organisations, businesses

and experts in innovative approaches ‘to revolutionise the delivery and

effectiveness of Australia’s aid program’.[101]

Under the initiative, all new aid investments are assessed for their ability to

‘explore innovative ways to promote private sector growth or engage the private

sector’.[102]

A warning

regarding this approach has been raised by Matt Tinkler from Save the Children,

who argues that ‘if private sectors are chasing commercial returns then by

their very nature they are unlikely to occur in the hardest to reach places’.[103]

Other NGOs have cautioned that ‘human rights and public interest must be

safeguarded when using development aid to leverage private finance, including

public-private partnerships’.[104]

One policy option

in this area that both the Abbott and Turnbull governments repeatedly ruled out,

however, is formally re-‘tying’ Australia’s aid to the use of Australian goods

and services in order to benefit local companies and exporters. DFAT Secretary Peter

Varghese highlighted soon after the integration of AusAID into DFAT that this former

policy, which was abolished in 2006, would not be revisited:

...it’s also important to understand that when the government

talks about aid and trade, they’re not talking about using the aid program to

promote Australian exports. Their front-of-mind concern is the role for the aid

program in building up the capacity of developing countries better to engage in

the international trading system.[105]

Despite a subsequent call from the JSCFADT to review this

policy (see below under ‘Parliamentary committee inquiries’), the principle of

untied aid was reaffirmed in the government’s 2015 aid-for-trade strategy:

This approach is consistent with the

Government’s commitment to openness in trade and competition. Untied aid is an

important way to ensure activities deliver value for money, are cost-effective

and use the best globally available expertise.[106]

The new

performance framework: changes to monitoring and evaluation

As part of

the changes relating to the aid program, the Coalition introduced a new strategic

framework for monitoring and evaluation. The June 2014 DFAT policy document, Making

Performance Count: Enhancing the Accountability and Effectiveness of Australian

Aid, detailed this framework which operates ‘across all levels of the aid

program’:

- At a strategic level, there will be 10 high level targets to

assess the aid program against key goals and priorities;

-

At a country, regional and partner program level, performance

benchmarks will be introduced to measure the effectiveness of our portfolio of

investments; and

- At a project level, robust quality systems will ensure that

funding is directed to investments making the most difference.

A key

principle underlying the framework is that funding at all levels of the aid

program will be linked to progress against a rigorous set of targets and

performance benchmarks.[107]

In order to put these principles into operation, the Office

of Development Effectiveness (ODE) and the Independent Evaluation Committee—aid

quality mechanisms established by the Howard and Gillard governments

respectively—were retained after the merger.

The ANU’s Development

Policy Centre raised some questions about this new approach,

including the removal of the previous practice of measuring the organisational reforms

associated with improved aid delivery. Under a previous

three-tiered performance framework adopted by the Gillard Government, corporate

reforms such as reducing excessive staff turnover were measured as part of the

third tier. While supportive of an approach that gives ‘more attention to

country and project performance, and using this information to direct more

money to better programs and projects’, the Center noted that variation from

year to year can be hard to measure, and that measuring the internal reforms of

an aid organisation was one of the few reliable ways to track effectiveness:

The worry is

that the three new tiers seem to have squeezed out the old third tier, which is

the most important. It is extremely difficult to measure aid results, and there

is little variation from year to year ... It is much easier to measure

organizational and operational performance. And we know that good organizations

will deliver good aid.

The sorts of

things that should be measured in the third tier are: how often staff change

positions; how transparent the aid program is; what the average aid project

size is; how timely decision making is; how well the various systems needed to

produce effective aid are working.

Yes, it’s

process, process, process. But don’t screw your nose up at it. Sometimes

process is the best and most important thing to measure. The aid program got

better at reporting on process with its old three-tier framework. For the first

time, the aid program started reporting, for example, how long staff were in

position. It would be sad if that start was reversed ... process should get more

not less profile in any new approach to aid effectiveness and results

reporting.[108]

The Centre has argued subsequently that transparency—an aspect

of aid management that has been nominated as worsening in recent surveys of aid

stakeholders—is one area where measures of organisational performance should be

assessed as part of the aid program’s annual reporting.[109]

Changes to

the aid program discussed earlier, such as reduced funding and loss of experienced

staff, could also impact on the ability of DFAT to effectively monitor the aid program.

As noted, Oxfam Australia argues that the effective evaluation of aid programs

requires reliable funding, as the project cycle can take years. Care Australia has

pointed out that losing experienced former AusAID staff could weaken the

ability of effective performance oversight—‘frequent shifts in policy, budget

and program objectives complicate relations with partners, disrupt program

delivery and make an assessment of impact and effectiveness difficult’.[110]

Another element of the changes is the emphasis on performance as ‘a

key criteria used to determine future budget allocations’.[111]

In June 2014, the Foreign Minister said that Australia, through

the use of performance-based aid, ‘will offer increased funding for programs

and organisations found to be particularly effective in meeting targets and

benchmarks’.[112]

While performance-based approaches have been generally supported in the

aid effectiveness literature, they also raise difficult questions. For example,

so-called ‘fragile’ or conflict-affected countries can present difficult and

costly operating environments in which progress is often slow. These countries are,

however, often also the ones most in need of assistance. The return on

investment could appear low—depending on exactly what criteria is used to

measure performance—and, as a result, those most in need could be excluded from

receiving aid. Some of Australia’s closest neighbours (such as PNG, East Timor

and the Solomon Islands) fall into this category.

Arguably, it is for this very reason that performance does not appear

to be being used to drive funding allocations at the country level. As an

analysis of these allocations in the 2015–16 Budget observes:

The Performance of Australian Aid 2013-14 report

released by DFAT last month shows very clearly where aid is performing well—in

East Asia, including Indonesia. These are the countries that have seen their

aid programs cut by 40 percent. The only two countries spared such cuts in East

Asia are the two worst performing ones: Timor Leste and Cambodia. Similarly,

the worst performing region, the Pacific and PNG, is the only one to have been

protected from the aid cuts.[113]

Similarly, at the sectoral level, areas such

as gender equality—which are often characterised by incremental progress and often

involve institutional or cultural change—are less amenable to the use of

performance incentives based simply on funding.

While these issues can be addressed through

effective planning—the new framework includes ‘aid investment plans’ that will

be ‘tailored to the different development contexts and priorities of the

countries we work in’— there remain multiple challenges to their application.[114]

Many of these challenges relate to the inevitable complexities and tensions

that arise in balancing considerations of aid effectiveness, varying indicators

of performance and multiple permutations of the ‘national interest’.

The Indo-Pacific

and increased consolidation

Two of the

ten ‘key targets’ in Making Performance Count are ‘focusing on the

Indo-Pacific region’ and ‘increasing consolidation’—that is, reducing the

number of individual investments to focus efforts and reduce transaction costs

for the donor and recipient countries.[115]

Both of

these strategies reflect international agreements on aid effectiveness to which

Australia has committed. The 2008 Accra Agenda for Action—a statement to

improve aid effectiveness signed by developing and donor countries, as well as multilateral

aid agencies—commits signatories to ‘reduce costly fragmentation of aid’.[116]

In the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness—the 2005 document agreed

prior to the Accra Agenda—donor countries commit to ‘make full use of their

respective comparative advantage at sector or country level’.[117]

Australia

has a clear comparative advantage in the Indo-Pacific region due to proximity

and knowledge, as well as long-standing relationships. In proportional terms,

most of Australia’s aid has traditionally gone to the Indo-Pacific, a region in which many countries are still developing and face

significant poverty issues. Even before the recent changes, Australian ODA

to the Indo-Pacific was already 86 per cent of country and regional aid.[118] According

to DFAT, the government’s changes increased this to around 92 per cent.[119]

The stated

goal of this consolidation is to ‘reduce the number of individual investments

by 20 per cent by 2016–17 to focus efforts and reduce transaction costs’.[120]

In its report, Performance of Australian Aid 2014–15, DFAT stated that progress

toward this goal was ‘on track’:

The aid program is on track to achieve this target within the

required timeframe. By 1 July 2015, the number of individual investments had

reduced by just over 18 per cent ... Other measures also show strong

consolidation in aid administration. Over the two years from July 2013 to July

2015, the average size of aid investments has increased by more than 20 per

cent. Over the same period, there has been a 27 per cent reduction in the

number of aid agreements (contracts and grant agreements) managed by DFAT, and

a 73 per cent increase in the average value of agreements under management.[121]

Given

ongoing funding reductions, the increased focus on the Indo-Pacific has not

translated into additional aid for the region. Over the four budgets bought

down by the Abbott and Turnbull governments, there has been a continuing decrease

in overall aid funding for most Indo-Pacific countries in East Asia and South

and West Asia, including both middle income countries such as Indonesia and

Vietnam, and low income countries such as Bangladesh and Afghanistan. As noted,

one notable exception in East Asia has been Cambodia. Aid to Pacific Island

countries, with the exception of PNG, has been subject to smaller reductions.

While acknowledging

that Australia has a particular obligation in relation to its region, groups

such as ACFID have emphasised the need to continue some assistance to Africa,

arguing that there ‘is good cause for continuing a strategic and modest focus

on aid and development assistance for Africa’ and that by 2012, ‘over 50 per

cent of the world’s poor lived in Africa’.[122]

Addressing

gender inequality

The Foreign

Minister has placed a very high priority on addressing gender inequality

through the aid program. One of the current strategic targets for Australia’s

overseas aid is that ‘more than 80 per cent of investments, regardless of their

objectives, will effectively address gender issues in their implementation’.[123]

The Foreign Minister has explained the development rationale behind this

target:

When women are able to actively participate in the economy, and in

community decision-making, everybody benefits ... Training women for employment,

building their capacity and challenging barriers to their participation will

deliver social and economic benefits to all societies. Evidence shows that it

is women who spend extra income promoting the health, education and well-being

of their families.[124]

The minister has also

highlighted the economic costs of gender inequality—‘it is estimated that the

Asia-Pacific alone loses around US$50 billion a year because of limited female

access to jobs and an estimated $30 billion a year is lost because of poor

female education’.[125]

While the previous

Labor government had committed to a strengthened focus on women and girls in

the aid program, the Coalition Government’s commitment to specific gender

equality funding targets was welcomed by NGOs, including the International

Women’s Development Agency (IWDA) and the child rights organisation, Plan

International. IWDA stated that the 80 per cent target ‘has the power to

transform the status of women’s rights across Asia Pacific’.[126]

Both of

these organisations, however, voiced some reservations about how the enhanced

commitment to gender equality will be delivered in the face of ongoing funding

reductions. IWDA said it was ‘pleased that the empowerment of women and girls

is stated as an overall priority for Australian aid’ but pointed to other cuts in

cross regional programs that risk having ‘a disproportionate impact on women

and girls, and slow[ing] progress towards gender equality’, including water and

sanitation, climate change and environmental sustainability, and governance.[127]

At the end of January 2015, Plan International argued that the government’s aid

cuts would have a disproportionate impact on girls and could mean that over the

financial year 2015–16:

- 220,000 fewer girls will be enrolled in school.

- 400,000 fewer girls will be immunised.

- 3,153 fewer classrooms where girls can learn will be renovated or built.

- 157,000 fewer girls will see improved access to safe drinking water.

- 750,000 fewer textbooks will be made available for girls.[128]

Nonetheless,

there has been some important progress. DFAT’s Performance of Australian Aid

2014–15 report, released in February 2016, observed:

...in 2014–15, 78 per cent of aid investments were rated as

satisfactorily addressing gender equality during their implementation, just

short of the target of 80 per cent. This was a significant improvement from the

2013–14 base line of 74 per cent.[129]

The report also

acknowledged, however:

...investments in the priority investment area of

“infrastructure, trade facilitation and international competitiveness”, on the

other hand, saw significantly lower ratings than the previous year with an

overall rating of 64 per cent satisfactory.[130]

In a 2014 evaluation

report, the ODE also highlighted the challenges in the economic empowerment

sector:

Australia has had less success integrating gender

equality into its key economic sector investments (agriculture, rural

development, transport, energy, trade and business and banking) compared to

sectors like health and education.[131]

The ODE also

noted that while ‘economic sector investments with a specific gender focus are

few and have not specifically focused on established pathways for women’s economic

empowerment’, this is something that ‘appears to be improving with new

policies, guidance and gender capacity’.[132]

In this

context, it is important to highlight that measurement of gender outcomes—even

defining what, precisely, should be measured—is a contested issue. The

Development Policy Centre notes that there remains some ambiguity in what the

80 per cent target actually means, noting that even aid projects which do not

have gender as a focus, can have a satisfactory score:

The [Smart Economics: Evaluation of

Australian Aid Support for Women’s Economic Empowerment] report reveals

that only 55 per cent of aid projects have gender as a significant or principal

objective. The other 45 per cent are not focused on gender equality.

The aid program’s performance management

system already requires every project to report on its gender progress, and all

projects are rated, regardless of whether gender is a focus. In that system, as

the ODE report shows, even projects which are not focused on gender can get a

satisfactory gender score. Indeed, the report shows that more than two-thirds

of projects for which gender is not a focus nevertheless report satisfactory

progress against gender.[133]

In the same

article, the authors note another concern with meeting the 80 per cent target—‘only

about one-third of Australian aid staff interviewed felt confident about how to

incorporate gender within a project cycle, and many pointed to a need for more

sector-specific advice’.[134]

It is no

surprise therefore, that there exists some confusion around incorporating

gender into projects and measuring results. This is widely recognised as a

complex area in which measures of progress can vary significantly depending on

the context. UN Women gives an indication of this complexity in one of its online

Guidance Notes:

There is no

single recipe for effectively monitoring and evaluating gender mainstreaming

efforts. Instead, gender-sensitive M&E systems must be innovative and

adaptable, and comprise a carefully selected suite of complementary approaches.[135]

This is also

reflected in research by the OECD, which recommends that gender indicators be adjusted

according to specific development contexts:

Although

there is often a temptation to simply apply universal templates and frameworks,

it is important to adapt gender equality indicators so they are relevant to the

specific context ...To be meaningful and illuminating, indicators need to be

derived in consultation with local people, and to reflect the context of a

particular region, country or community. [136]

This issue

of complexity is important as DFAT has already raised concerns about the lack

of effective monitoring and evaluation of gender-related outcomes, and limited

staff understanding in this area:

Only

one-quarter of the initiatives reviewed reported any gender-related outcomes

and only at the simplest level— sex-disaggregated data on participation in

training, and uptake of services. There was a lack of department-wide guidance on

how to structure and implement a monitoring and evaluation plan to assess gender-related

outcomes.[137]

The difficulties

associated with measuring gender outcomes are also worth emphasising in the

context of the changes the Foreign Minister has announced in the way aid will

be measured, the impact of staff cuts and the reduced budget. As discussed previously,

reporting is being simplified, some monitoring and evaluation expertise has

been lost through staffing cuts, and the lack of certainty around funding could

negatively affect forward planning. This is likely to make an already

challenging task even more difficult.

In addition,

if future funding is dependent on showing strong results, this could risk

creating incentives to design indicators that are easy to attain, rather than

indicators that most accurately measure actual development outcomes. It could

also risk providing incentive to omit ‘negative’ indicators, such as increased reporting

of domestic violence.

Climate change

Climate change was an area of significant change and readjustment

under the Abbott and Turnbull governments, moving from an issue that received comparatively

little attention under the Abbott Government to one which gained a high profile

under the Turnbull Government in late 2015.

The Labor Government’s 2013‒14 aid budget statement, mentioned

‘climate change’ 76 times in 160 pages, including in the ‘strategic goals’.[138]

The statement estimated environment-related expenditure to be around $600

million for the financial year.[139]

In contrast, the Abbott Government’s 2014‒15 budget

document, at 60 pages, contained only three references to ‘climate change’, a

further one to ‘climate variability’ and two to ‘climate-related events’ and

‘climate-related shocks’.[140]

Nor did it contain an overall estimate for total environment or climate change expenditure.

This reflected the view put by Julie Bishop from Opposition in December 2012:

Climate change funding should not be disguised as foreign aid

funding. That’s been the view of the United Nations and yet this government

still continues to do it. We would certainly not spend our foreign aid budget

on climate change programs.[141]

Given the region’s

particular vulnerability to the impacts of climate change, some NGOs argued that

this lack of attention to climate change was at odds with Australia’s

long-standing commitment to, and focus on, the development needs of the Pacific

Island countries.[142]

According to Oxfam Australia:

Millions of the world’s poorest

people are already bearing the brunt of climate change because of its damaging

effects on their livelihoods, food security and peace. Our concern about

ongoing funding for climate adaptation has arisen because of the recent budget

cuts to the overall volume of aid to several ‘climate vulnerable’ Pacific

nations, as well as a 97% cut for ‘Climate Change and Environmental

Sustainability’ under ‘Cross Regional Programs’ and the elimination of all contributions

to ‘Global Environment Programs. ...Pacific governments, development agencies and

scientific bodies, have consistently recognized climate change as a major

challenge to sustainable economic development in the Pacific.[143]

There were some adjustments under the Abbott Government. For

example, while initially ruling out contributing to the international Green

Climate Fund, the Abbott Government reversed this position in late 2014 with

the announcement that it would provide $200 million over four years to the organisation.[144]

Foreign Minister Bishop stated that this commitment:

...will facilitate private sector-led economic growth in

our region—the Indo-Pacific—it will be targeted in our region with a particular

focus on investment in infrastructure, energy, forestry and the like.[145]

More significant changes followed establishment of the

Turnbull Coalition Government in September 2015. In the lead-up to a major UN climate

change summit in Paris in December 2015, there was significant domestic and

international pressure on the government to provide additional financial aid to

help developing countries meet their greenhouse gas reduction targets and adapt

to the impacts of climate change.[146]

Some of the strongest pressure came from Australia’s Pacific neighbours.[147]

At the Paris summit, Prime Minister Turnbull announced that Australia would

allocate at least $1 billion over five years from the existing aid budget to

help developing countries ‘build climate resilience and reduce emissions’.[148]

Environment groups such as the Climate Institute and the

World Wide Fund for Nature welcomed this pledge as ‘encouraging’. They also argued

it fell short of the $1.5 billion per year estimated as Australia’s ‘fair

contribution’.[149]

Some development NGOs criticised the commitment on the grounds that it was not

additional funding and as a result, would potentially result in more cuts to

existing programs in areas such as health and education. Plan International

stated:

...it is deeply disappointing to see the Prime Minister’s $1

billion commitment is not a new commitment, but rather a repurposing of funds

already earmarked for Australia’s aid program. What we are seeing here is the

Government robbing Peter to pay Paul—not something the developing world can

afford on the back of years of the most savage cuts we have ever seen in our

aid program.[150]

Other groups, including ACFID, observed that Australia was

already spending close to $200 million a year on climate change aid and accused

the government of ‘repackaging [existing] announcements’.[151]

In Senate Additional Estimates hearings in February 2016, DFAT confirmed that it

had spent $229 million on climate change-related aid activities in 2014–15.[152]

The 44th Parliament

and Australia’s overseas aid program

Parliamentary

Committee inquiries

The 44th Parliament expressed a strong interest in aid and

development issues, including through several inquiries conducted by relevant

parliamentary committees. While providing an opportunity for bipartisanship on

some issues, it is important to note that many of the findings and

recommendations of these inquiries reflected their political composition; the

Opposition chaired the SFADT References Committee and non-government parties

held a majority, while the government chaired and held the majority on the JSCFADT.

‘Australia’s

overseas aid and development assistance program’, SFADT References Committee, 2014

The 44th

Parliament’s first major examination of aid issues commenced in December 2013

when the Senate referred issues relating to Australia’s overseas aid and development

assistance program to the SFADT References Committee. In light of the government’s

cuts the aid budget, the committee was tasked with assessing the government’s

ability to deliver aid in accordance with policy objectives and international commitments

and priorities, including sectoral, regional, bilateral and multilateral

partnerships. In addition, the inquiry sought to investigate the consequences

of AusAID’s integration into DFAT and the freeze in international development

assistance funding.[153]

The committee

reported in March 2014. The majority report made 24 recommendations. These emphasised

the importance of long-term planning and predictability to the aid budget,

recommending that the government release a policy framework for aid as part of

the 2014 budget process and produce a white paper to identify Australia’s

long-term aid objectives and the means to achieve them. It also recommended

that the government should ensure that the ODA/GNI ratio does not fall below

0.33 per cent and that both major parties develop a bipartisan agreement to

increase the Australian aid budget in order to achieve the ODA/GNI target of

0.5 per cent by 2024–25.[154]

A dissenting

report from the committee’s Coalition members recommended that the aid program should

continue to: deliver against the government’s stated policy objective of

promoting Australia’s national interests through contributing to economic

growth and poverty reduction; implement rigorous performance benchmarks; and

strengthen fraud management controls and systems.[155]

A dissenting

report from the Australian Greens reiterated the party’s commitment to the UN

Millennium Development Goal target of 0.7 per cent ODA/GNI by 2015, the

delinking of aid from asylum seeker policies and the reinstatement of AusAID as

an executive agency.[156]

While the government’s

response either did not agree to, or simply ‘noted’, most of the committee’s

recommendations, it did agree to release a new policy framework for the aid

program.[157]

This framework, Australian Aid: Promoting Prosperity, Reducing Poverty, Enhancing

Stability, was published in June 2014.[158]

‘The role

of the private sector in promoting economic growth and reducing poverty in the

Indo-Pacific’, JSCFADT, 2015

The June 2015 final report of a JSCFADT inquiry into ‘the

role of the private sector in promoting economic growth and reducing poverty in

the Indo-Pacific region’ made 37 recommendations. The recommendations called