Dr Matthew Thomas and Geoff Gilfillan

Youth unemployment

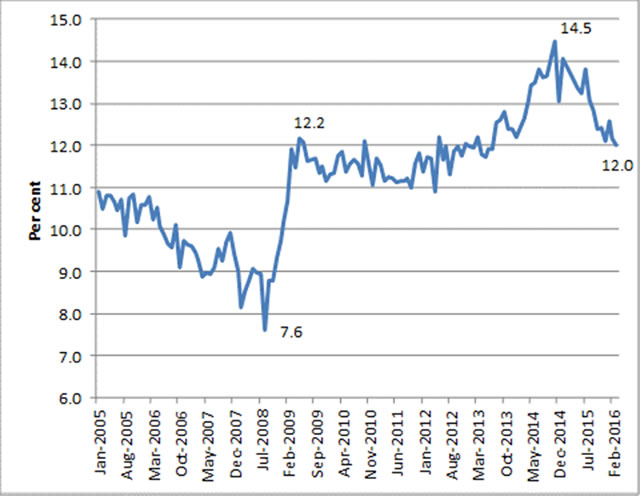

The labour market for youth aged 15 to 24 years deteriorated

substantially after the onset of the Global Financial Crisis in 2008 and has

only recently shown signs of recovery. Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS)

data show that the youth unemployment rate rose sharply from its most recent

low of 7.6 per cent in August 2008 (in seasonally adjusted terms) to 12.2 per

cent in May 2009.[1] The youth unemployment

rate then rose to 14.5 per cent in November 2014 but has since fallen to 12.0

per cent in March 2016. See graph below.

Unemployment rate for people aged

15 to 24 years (seasonally adjusted data)

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Labour force,

Australia, cat. no. 6202.0, ABS, Canberra, March 2016.

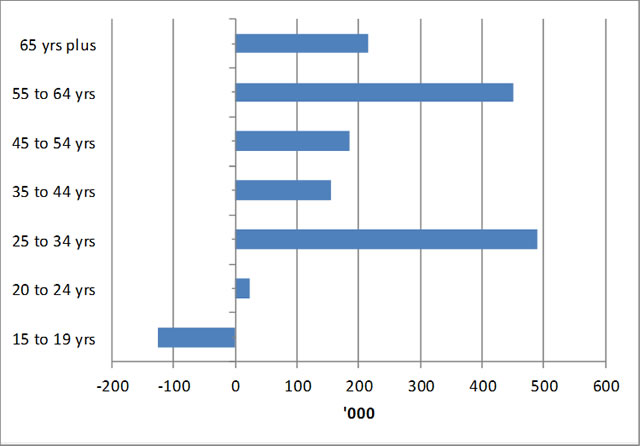

Young people appear to have borne the brunt of softening in

the labour market since early 2008. In contrast to people in other age groups,

employment for people aged 15 to 19 years contracted by 125,000 between January

2008 and March 2016 and employment for those aged 20 to 24 years only grew by

23,000. See graph below.

Change in employment by age group

(original data) — January 2008 to March 2016

Source:

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), ABS, Labour

force, Australia, detailed—electronic delivery, cat. no. 6291.0.55.001,

ABS, Canberra, March 2016.

Youth employment measures

In response to the problem of youth unemployment, the

Government introduced a youth employment strategy as a part of the 2015–16

Budget.[2] This year’s Budget includes

a Youth Employment Package which consists of two major new youth employment

measures and the revision of the Work for the Dole program. The Government has

also abolished the Job Commitment Bonus. As such, the Government’s strategy to

tackle youth unemployment can be seen as being consistent with its stated general

approach to social welfare, under which ‘policies that are found to be

effective will be continued or enhanced, while ineffective policies will be

improved or ceased, with funding made available to new approaches’.[3]

The Job Commitment Bonus will cease from 31 December 2016,

realising savings of $242.1 million over five years.[4]

The Bonus, which was introduced by the Government as a part of the December

2013 Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook and legislated through the Social

Security Legislation Amendment (Increased Employment Participation) Act 2014,

was intended to provide an incentive for long-term unemployed job seekers to

find and take up ongoing paid employment.[5] As was noted in the Bills

Digest for the legislation that enabled the Bonus, the measure was an

experimental one in Australian terms, and one for which the rationale and

likelihood of success was unclear.[6]

The Government has also made changes to the Work for the

Dole Program that are anticipated to generate savings of $494.2 million over

the forward estimates period.[7] Under the measure, the

most job-ready job seekers (Stream A job seekers) will be required to

participate in Work for the Dole after 12 months’ participation in jobactive

rather than six months.[8] This will give these job

seekers a greater opportunity to gain employment or to participate in programs

that may improve their employability before undertaking Work for the Dole, a

program whose impacts in terms of employment outcomes is modest. According to

the findings of a recent evaluation of the impact of the Work for the Dole

program, conducted by researchers from the Australian National University’s Centre

for Social Research and Methods, participation in the program resulted in only a

1.9 percentage point increase in job seekers’ prospects of gaining employment.[9]

The savings from the above measures are being redirected to

‘repair the Budget and fund policy priorities’.

The centrepiece of the Youth Employment Package is the Youth

Jobs PaTH program. This program, which is to be established at a cost of $751.7

million over four years from 2016–17, is intended to provide job seekers aged

under 25 years who have been in receipt of jobactive services for at

least six months with real work experience, and to maximise their prospects of

subsequently gaining employment.[10]

Under the program, following training of up to 6 weeks in

basic employability skills, up to 120,000 job seekers will be offered internship

placements of 4 to 12 weeks over a four-year period. Participation in the

program will be voluntary, with those job seekers who do take part working for 15

to 25 hours per week.[11] Job seekers will receive

$200 a fortnight in addition to their income support payment and businesses

will receive an up-front payment of $1,000 for hosting job seekers. If the host

businesses (or any other employers of job seekers aged under 25 years and in

receipt of jobactive services for at least six months) offer young job

seekers a job, they will be eligible for a wage subsidy of up to $6,500 for

job-ready job seekers and up to $10,000 for disadvantaged job seekers. Under

the changed wage subsidy arrangements discussed below, the subsidies will be

paid on a flexible basis.

As long as young people are provided with quality work

experience and acquire skills for which there is likely to be employer demand,

the program could prove successful. Australian Council of Social Service CEO,

Dr Cassandra Goldie is reported as having argued that the program is more

likely than Work for the Dole to help young people into paid employment, and

emphasised that ACOSS supports the belief that work experience can improve job

opportunities.[12]

While there has been some criticism of the program on the

grounds that it involves businesses paying participants around $4 an hour, an

amount that is substantially less than the minimum wage of $17.29, this does

not account for the fact that the payment is in addition to the job seeker’s

income support payment.[13] That said, a number of

commentators have also expressed concerns that without appropriate safeguards

the program could be used by businesses to replace existing workers or as an

alternative to recruiting young workers at the appropriate wage.[14]

While, as noted above, ACOSS is generally supportive of the program, Cassandra

Goldie shared these concerns, and observed that careful monitoring and

protections would be needed to guard against the risks of worker displacement.[15]

It should be noted that it is difficult to tell from the

budget papers how the Youth Jobs PaTH program will lead to a cost of $751.7

million, as the figures presented only add up to around $244 million.[16]

The description of the wage subsidies component of the measure suggests that

the remaining funding may be made up of existing wage subsidy funding, which

has been reallocated from the jobactive program. If so, then the amount

of the funding reallocated appears to be in the region of $300 million. The

budget papers state that the Government will achieve savings of $204.2 million,

and suggest that these will be gained as a result of the streamlining of wage

subsidy payments, discussed below.

Under another of the Budget’s measures, wage subsidies are

to be made more flexible, with the subsidies to be paid earlier and in a manner

that better suits businesses.[17] The reform of wage

subsidy arrangements is likely to improve employer take-up of the subsidies,

which can help to improve long-term employment outcomes for job seekers.[18]

However, the changes may also increase the risk of some employers taking on job

seekers for shorter periods while the subsidy is available, and then either putting

them off or reducing their hours when the subsidies have run out. Typically,

wage subsidies are either structured with a relatively small up-front payment

and most of the subsidy paid at the conclusion of the payment period or paid in

regular instalments so as to avoid this problem. As such, use of the new wages

subsidy arrangements by employers will need to be monitored and reviewed.

The Budget provides $88.6 million over the forward estimates

period for the expansion of the New Enterprise Incentive Scheme (NEIS) and

initiatives to encourage and assist young people into self-employment.[19]

Under the NEIS, a person is paid an NEIS allowance that is equivalent to the

basic single rate of Newstart Allowance for up to 12 months free of any job

search or mutual obligation requirements, as long as the recipient is

establishing a new business. The expansion of the NEIS to 8,600 places per

annum, and the inclusion of people not in receipt of income support, is a

positive step.[20] A number of evaluations

of the NEIS have been conducted over the years, and, generally speaking, the

findings of these evaluations in terms of self-employment outcomes and flow-on

effects have been positive.[21]

[1].

The labour force data in this brief have been taken from the following

product unless otherwise sourced: Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Labour force,

Australia, cat. no. 6202.0, ABS, Canberra, March 2016; ABS, Labour

force, Australia, detailed—electronic delivery, cat. no. 6291.0.55.001,

ABS, Canberra, March 2016.

[2].

For a brief description and analysis of the measures see M Thomas, ‘Workforce

participation measures’, Budget review 2015–16, 2015–16,

Parliamentary Library, Canberra, 2015, pp. 154–156.

[6].

M Klapdor and M Thomas, Social Security Legislation Amendment

(Increased Employment Participation) Bill 2014, Bills digest, 48, 2013–14,

Parliamentary Library, Canberra, 2014. According to an answer to a question on

notice posed by Senator Sue Lines, ‘as at 15 November 2014, 16,356 individuals

were potentially tracking toward claiming the Job Commitment Bonus, that is,

they were aged 18 to 30 while receiving Newstart Allowance or Youth Allowance

(other) for 12 months or more, but now have left, and are still off, income

support’. Senate Standing Committee on Education and Employment, Answers to

Questions on Notice, Employment Portfolio, Supplementary Budget Estimates 2014–15,

Question

EM1632_15.

[8].

The measure will realise significant savings because there are far

fewer eligible young job seekers at the 12 month point than at the six month

point.

[11].

Australian Greens Senator Rachel Siewert has argued that while

participation in the program has been presented as being voluntary, it has the

potential to become compulsory, in effect: ‘people shouldn’t be fooled by the

rhetoric that this is voluntary because if a job service provider puts it into

a person’s job plan it essentially becomes compulsory as penalties apply if

someone doesn’t support their plan’. K Silva, P McDonald and T Taylor, Budget

2016: jobseekers weigh up internship program but experts fear workers could be

exploited, ABC News, 4 May 2016.

[21].

For example: R Kelly, P Lewis, M Dockery and C Mulvey, Findings

in the NEIS Evaluation: report prepared for the Department of Employment,

Workplace Relations and Small Business, Centre for Labour Market Research, Murdoch

University, 2001, pp. 62–3 and A Dockery, ‘The

New Enterprise Incentive Scheme: an evaluation and test of the Job Network’,

Australian Journal of Labour Economics, 5/3, 2002, pp. 351–71.

All online articles accessed May 2016.

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.

In essence, you are free to copy and communicate this work in its current form for all non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute the work to the author and abide by the other licence terms. The work cannot be adapted or modified in any way. Content from this publication should be attributed in the following way: Author(s), Title of publication, Series Name and No, Publisher, Date.

To the extent that copyright subsists in third party quotes it remains with the original owner and permission may be required to reuse the material.

Inquiries regarding the licence and any use of the publication are welcome to webmanager@aph.gov.au.

This work has been prepared to support the work of the Australian Parliament using information available at the time of production. The views expressed do not reflect an official position of the Parliamentary Library, nor do they constitute professional legal opinion.

Any concerns or complaints should be directed to the Parliamentary Librarian. Parliamentary Library staff are available to discuss the contents of publications with Senators and Members and their staff. To access this service, clients may contact the author or the Library‘s Central Entry Point for referral.