Daniel Weight

The Government has stated that there have been significant reductions, or ‘writedowns’, in Commonwealth revenues, particularly from profits based taxes.[1] However, others have asserted that revenues have, in fact, increased.[2] Depending upon how revenue is measured, both of these assertions may be correct.

The briefing entitled Revised revenue projections and associated expenditure for the Minerals Resource Rent Tax (MRRT) specifically discusses revenues from that tax.

Measures of revenues

The Government, Opposition, and other commentators all tend to use differing bases for their assertions, making direct comparisons difficult. There are several areas where ambiguity can arise.

‘Tax’ revenue or ‘total’ revenue

Differing pictures of the revenue available to the Government can emerge depending upon whether tax revenue or total revenue is being discussed. The majority of revenue received by the Government is classified as taxation. Taxation cash receipts are estimated to be $354.9 billion in 2013–14.[3] However, the Government also receives certain other revenues from the provision of goods and services, dividends, and interest. Other cash receipts are expected to be $21.1 billion in 2013–14.[4] Total cash revenue includes both taxation revenue and other revenue, and is estimated to be $376.0 billion in 2013–14.

‘Nominal’ versus ‘real’ growth in receipts

Due to the tendency of prices to increase due to inflation, the nominal value of revenue receipts can be misleading as it is not adjusted for the effects of inflation. Therefore, the annual increase (or decrease) in revenue receipts is sometimes adjusted for inflation to arrive at a ‘real’ rate of increase (or decrease) in revenue.

Focusing on the real rate of revenue growth may provide a better picture of the true level of revenues to Government. An assertion that revenue is down in real terms may be difficult to reconcile with nominal figures that show a simple arithmetic increase. Since the 2008–09 Budget, the Government has used the Consumer Price Index (CPI) to adjust nominal budget figures to arrive at real figures.[5]

Receipts as a per cent of Gross Domestic Product

Another measure of revenue receipts that has been cited is taxation receipts as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP). On the assumption that the Government’s revenue receipts will generally remain a constant proportion of the economic activity occurring within Australia, this measure can provide a useful insight into whether or not taxation receipts are higher or lower than could otherwise be expected.

Revenue ‘write-ups’ and ‘write-downs’

Another measure of how revenue has moved is how the most recent forecasts of revenue receipts have varied from prior estimates. This complication arises from the Government’s annual budgeting process, which assumes a certain level of growth in receipts from factors including general price inflation and increased economic activity. Variations in these two factors, in particular, can mean that a forecast for certain types of revenue vary as the estimates evolve throughout the four year budget period.

It is entirely reasonable in most circumstances for Governments to anticipate increases in revenues in future years when formulating their annual budget and making spending decisions. However, such an approach relies heavily upon the robustness of underlying economic and other forecasts.

Is revenue ‘up’ or ‘down’?

Given that there are various differing measures of revenue receipts, it is worthwhile determining whether revenues have risen, or are expected to rise, according to the various measures presented.

Nominal revenue growth

Table 1 shows the actual and estimated total revenue and taxation revenue receipts between 2004–05 and 2015–16 on a cash basis and the percentage change.

Table 1: Nominal total and tax revenues (2004–05 to 2015–16)

|

04–05

|

05–06

|

06–07

|

07–08

|

08–09

|

09–10

|

10–11

|

11–12

|

12–13

|

13–14

|

14–15

|

15–16

|

|

Total revenue

|

|

($b)

|

236.0

|

255.9

|

272.6

|

294.9

|

292.6

|

284.7

|

302.0

|

329.9

|

350.4

|

376.0

|

401.2

|

428.9

|

|

Change (%)

|

8.4

|

8.5

|

6.5

|

8.2

|

-0.8

|

-2.7

|

6.1

|

9.2

|

6.2

|

7.3

|

6.7

|

6.9

|

|

Tax revenue

|

|

($b)

|

223.3

|

241.2

|

257.4

|

278.4

|

272.6

|

261.0

|

280.8

|

309.9

|

326.3

|

354.9

|

377.8

|

405.8

|

|

Change (%)

|

8.4

|

8.0

|

6.7

|

8.2

|

-2.1

|

-4.3

|

7.6

|

10.4

|

5.3

|

8.8

|

6.5

|

7.4

|

Note: 2012–13 to 2015–16 are estimates.

Source: Australian Government, 2013–14 Budget papers: budget paper no. 1: budget strategy and outlook, p. 10–6 and 10–7, 14 May 2013, accessed 24 May 2013.

On these measures, both total and tax revenues decreased during the height of the global financial crisis in 2008–09 and 2009–10. However, both total revenues and tax revenues rebounded strongly in 2011–12. The forecasts for both total revenues and tax revenues show continued growth to 2015–16, albeit at generally lower rates than prior to the global financial crisis (GFC).

Real revenue growth

When the expected increase in revenues is adjusted for general price inflation (as measured by the CPI), the general picture that emerges from the outcome and estimates of nominal revenues remains the same (see Table 2). That is, Government revenues—whether total or only tax—only declined in 2008–09 and 2009–10.

Table 2: Real change in total and tax revenues (2004–05 to 2015–16)

|

04–05

|

05–06

|

06–07

|

07–08

|

08–09

|

09–10

|

10–11

|

11–12

|

12–13

|

13–14

|

14–15

|

15–16

|

|

Total revenue

|

|

Change (%)

|

5.7

|

5.8

|

2.4

|

6.0

|

-5.0

|

-4.1

|

2.9

|

5.5

|

5.0

|

4.7

|

4.4

|

4.7

|

|

Tax revenue

|

|

Change (%)

|

5.7

|

5.4

|

2.6

|

5.9

|

-6.2

|

-5.6

|

4.4

|

6.6

|

4.0

|

6.1

|

4.2

|

5.2

|

Note: 2012–13 to 2015–16 are estimates.

Source: Australian Government, 2013–14 Budget papers: budget paper no. 1: budget strategy and outlook, p. 10–6 and 10–7, 14 May 2013, accessed 24 May 2013; ABS, Consumer price index, cat. no. 6401.0, accessed 24 May 2013.

Receipts as a percentage of GDP

When we look at revenues as a proportion of GDP, the effect of the GFC becomes more pronounced (see Table 3). At the height of the GFC, both total revenues and tax revenues declined from their most recent highs in 2004–05 by 3.2 per cent and 4.2 and of GDP respectively. As shown in Table 3, both total revenues and tax revenues as a percentage of GDP are not forecast to exceed their pre-GFC highs at any point to 2015–16.

Table 3: Revenue as a percentage of GDP (2004–05 to 2015–16)

|

04–05

|

05–06

|

06–07

|

07–08

|

08–09

|

09–10

|

10–11

|

11–12

|

12–13

|

13–14

|

14–15

|

15–16

|

|

Total revenue

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

% GDP

|

25.6

|

25.7

|

25.2

|

25.1

|

23.3

|

22.0

|

21.5

|

22.4

|

23.0

|

23.5

|

23.9

|

24.3

|

|

|

Tax revenue

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

% GDP

|

24.2

|

24.2

|

23.8

|

23.7

|

21.7

|

20.2

|

20.0

|

21.0

|

21.5

|

22.2

|

22.5

|

23.0

|

|

Note: 2012–13 to 2015–16 are estimates.

Source: Australian Government, 2013–14 Budget papers: budget paper no. 1: budget strategy and outlook, p. 10–8, 14 May 2013, accessed 24 May 2013; ABS, Consumer Price Index, cat. no. 6401.0, accessed 24 May 2013.

On this measure, the Government has faced a significant fall in both tax and total revenue receipts.

Write-downs to revenue

In the 2013–14 Budget, total revenue (on a cash basis) in 2013–14 is forecast to be $16.6 billion less than was forecast at the time of the 2012–13 MYEFO in October 2012. [6] Of this reduction, $14.9 billion is attributable to downward revisions to tax receipts.[7] To the extent that this represents a variation from a prior estimate, it is a ‘loss’ to the revenue that was anticipated to be received by the Government, but not a loss of any revenues ever actually received. The Government has stated that the most significant write-down to revenue relates to company tax.[8]

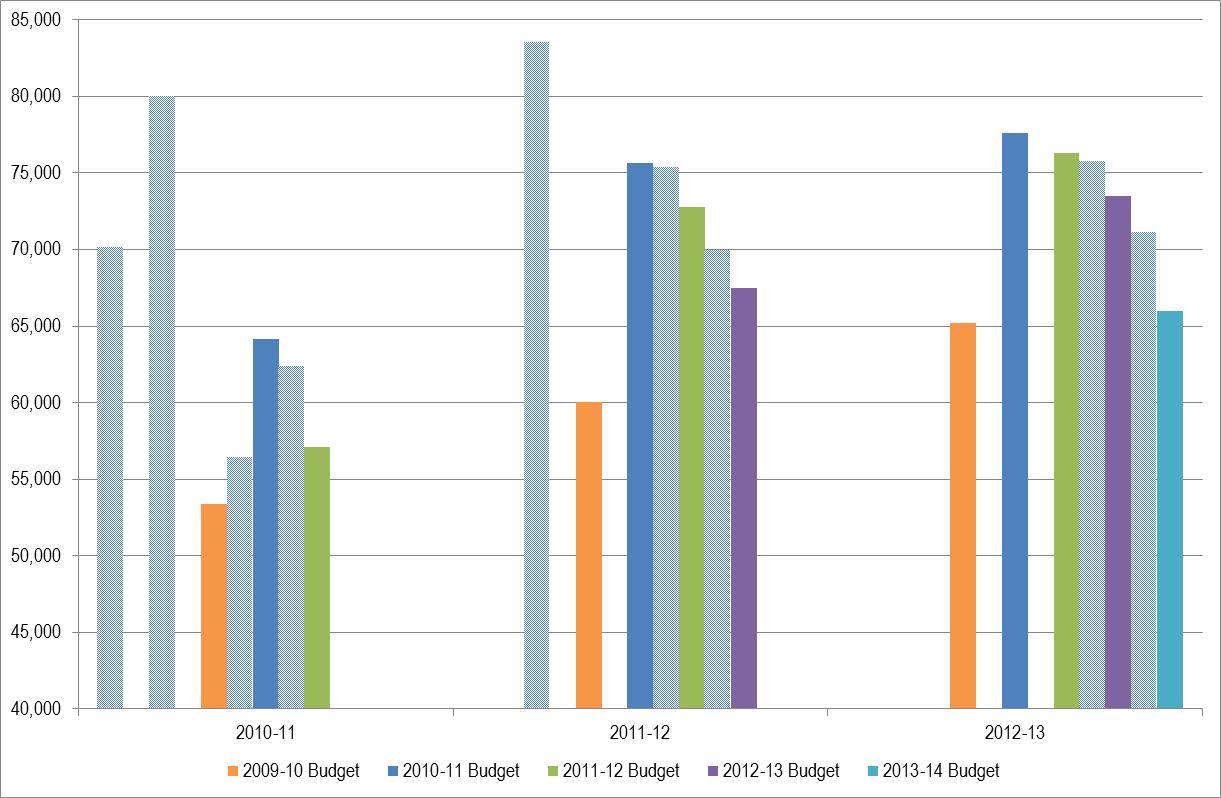

Estimates of revenues start out as projections four years ahead, but as subsequent budgets and other updates to the forecasts are issued, a clearer picture of the likely final outcome for a given year emerges. As an example, Chart 1 shows the evolution of the figure for company tax cash receipts for the years 2010–11 to 2012–13 with selected forecasting points highlighted.

Chart 1: Evolution of company tax forecasts 2010–11 to 2012–13 (selected forecasting points)

Note: Abridged scale.

Source: Australian Government, Budget paper no. 1: budget strategy and outlook (various years) accessed 24 May 2013; Australian Government, Mid year economic and fiscal outlook (various years), accessed 24 May 2013.

At the height of the GFC in 2009–10, the Government’s projections of company tax revenues for the relevant years were lower than any other point. However, the next set of estimates made as part of the 2010–11 Budget forecast a significant upward revision to company tax receipts. In the three subsequent budgets to 2013–14, company tax receipts were revised down in all years considered above.

To the extent that the Government may have relied upon receiving levels of company tax revenues forecast in the 2010–11 Budget, it has ‘lost’ revenue. Given that company tax receipts for 2010–11 exceed the estimate made during the height of the GFC only one year before, adopting optimistic estimates in the 2010–11 Budget may have been reasonable. However, the subsequent write–downs of revenues for the 2011–12 and 201–13 years tend to suggest that the forecasts of company tax receipts made for the out years in the 2010–11 Budget were too optimistic.

[1]. W Swan (Deputy Prime Minister and Treasurer), Interview with Fran Kelly, Radio National Breakfast, Budget 2013–14, transcript, 15 May 2013, accessed 24 May 2012.

[6]. Australian Government, Budget strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1: 2013–14, p. 5–30, 14 May 2013, accessed 24 May 2013.

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

In essence, you are free to copy and communicate this work in its current form for all non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute the work to the author and abide by the other licence terms. The work cannot be adapted or modified in any way. Content from this publication should be attributed in the following way: Author(s), Title of publication, Series Name and No, Publisher, Date.

To the extent that copyright subsists in third party quotes it remains with the original owner and permission may be required to reuse the material.

Inquiries regarding the licence and any use of the publication are welcome to webmanager@aph.gov.au.

This work has been prepared to support the work of the Australian Parliament using information available at the time of production. The views expressed do not reflect an official position of the Parliamentary Library, nor do they constitute professional legal opinion.

Feedback is welcome and may be provided to: web.library@aph.gov.au. Any concerns or complaints should be directed to the Parliamentary Librarian. Parliamentary Library staff are available to discuss the contents of publications with Senators and Members and their staff. To access this service, clients may contact the author or the Library‘s Central Entry Point for referral.