Bill McCormick, Science,

Technology, Environment and Resources

Key Issue

Many Regional Forest Agreements are likely to be extended when they expire during this term of Parliament.

Significant changes to land clearing legislation are proposed for both Queensland and New South Wales, with potentially different outcomes.

Native vegetation, such as forests, has many

benefits including supporting biodiversity, reducing

land degradation and salinity, improving water quality, storing carbon, and

contributing to on-farm production.

Australia’s

State of the Forests Report 2013 said that

there are over 19,000 species of vertebrates and plants

found in Australia’s forests. 1,431 forest-dwelling species are listed as

threatened due to habitat loss from land clearing for agriculture, grazing, and

urban and industrial development as well as predation and competition from pest

and unsuitable fire regimes. The report said that forestry operations pose a

minor threat to these threatened forest-dwelling fauna and flora species.

Australia’s forests

Forests comprise just 125

million hectares (ha), or 16% of Australia’s total land area. Of this, 123 million ha is

native forests and 2 million

ha plantations. Only 36.6 million ha of native forests are available and

suitable for wood production, of which 7.5

million ha are in public native forests.

There has been a 63% decline in log production from

native forests of 10.4 million cubic metres (m3) in 2003–04 to 3.9 million m3 in 2014–15. This compares to a 46% increase from 16 million m3

to 24.5 million m3 from plantations. This is the result of structural

change in the industry which has led to a significant decline in native

hardwood logs for woodchip export, but a 280% increase in plantation hardwood

logs. Around 70,500

people were employed in the forestry and forest products industry in 2013–14.

Regional Forest Agreements

Issues associated with native forestry have been controversial

for the past forty years; Commonwealth involvement in

native forestry activities started with the regulation of woodchip exports in

the 1970s. Conservation groups have sought to convince state and federal

governments to include old growth forest and wilderness in conservation

reserves. In 1995, the Comprehensive Regional Assessment process aimed to find

a long-term solution by identifying areas for protection and areas to be open for

harvesting in order to enable certainty of future wood supply. Regional Forest Agreements (RFAs) were

then agreed between the federal and state governments, protecting 90% of wilderness and 60% of

old-growth forests in reserves. Ten RFAs were signed between 1997 and 2001,

covering four states:

RFAs apply for 20 years, with five-yearly reviews. As

such, they are due to expire in the next few years. However, each RFA may be

extended for a further period after the third five-year review of the RFA.

The 2013 Coalition

forestry policy stated that it would extend the

RFAs for five years following each five-year review,

starting with the Tasmanian RFA. The third five-year

review of the Tasmanian RFA has been finalised. In

its response, the indicated they would extend the RFA into a rolling 20-year

agreement. Tasmania will be entering formal negotiations over the RFA extension

with the Australian Government.

The agreed process

for the Tasmanian RFA may be a template for the RFAs in other states. All three

other states have agreed

to pursue their reviews in 2016. However, the Victorian

Government has not decided its position about the extension of its RFAs. It is

still considering whether to establish more national parks in forest areas of

Victoria. In November 2015, it established a Forest Industry Taskforce, which has yet to report.

The establishment of RFAs has not halted significant

public opposition to the continued logging of old growth forests and there are

now campaigns from conservation groups to end all logging in native forests.

While both the Coalition and the ALP support the continuation of the

RFAs, the Greens want to phase out logging in

native forests.

Vegetation clearing

Clearing of native

vegetation can have a number of serious consequences such as biodiversity

decline, dryland salinity, reduced water quality and quantity, difficulty in

flood control, increased erosion, increased greenhouse gas emissions and

reduced ecosystem functioning (facilitating biological insect pest control).

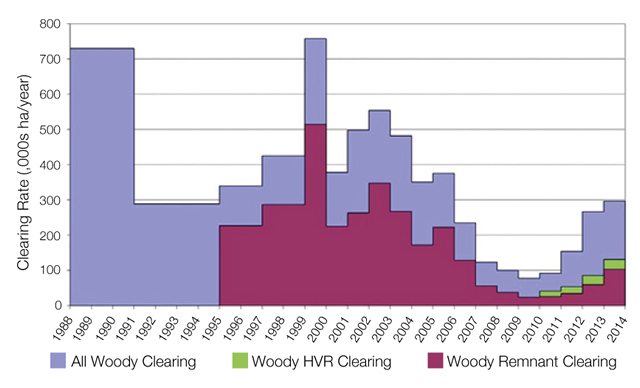

Figure 1: Annual woody vegetation clearing rate in Queensland

(1988–2014)

Source:

Land

cover change in Queensland 2012–13 and 2013–14 Statewide Landcover and Trees

Study

Note that HVR stands for high

value regrowth vegetation

High levels of land clearing in the early 1990s led

Commonwealth, state and territory governments

to set the goal of reversing the decline in the quality and extent of native

vegetation by 2001. Australia’s

Native Vegetation Framework updates a 2001 framework

that aimed to implement this goal.

The 2001 target was not met and more than 400,000

ha was still being cleared annually, with the great majority being cleared in

Queensland along with significant areas in NSW. These states implemented more

stringent vegetation management controls from 2006. They resulted in a decrease

in land clearing with greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) from deforestation across

Australia decreasing from 98

megatonnes (Mt) of carbon

dioxide equivalent (CO2-e) in 1991 (19% of Australia’s GHG

emissions) to just 34 Mt CO2-e in 2014 (6.5%).

Change of governments in Queensland (2012) and NSW

(2011) resulted in a loosening of the restrictions on land clearing in both

states.

In the case of Queensland there was a tripling in the

rate of land clearing from less than 100,000 ha in 2011 to 300,000 ha in

2014 (see Figure 1 above). According

to the Queensland Government, land clearing in Queensland is now generating

a substantial proportion of Australia's GHG emissions from deforestation.

The newly elected Queensland government is

attempting to reverse

this trend, and protect the Great Barrier Reef, by introducing new

legislation that will:

- reinstate the protection of high-value regrowth

on freehold and Indigenous land

- remove provisions permitting clearing for

high-value agriculture

- broaden protection of regrowth vegetation in

watercourse areas to cover all Great Barrier Reef catchments

- reinstate compliance provisions for vegetation

clearing offences and

- regulate against the destruction of vegetation

in watercourses.

The Australian Conservation Foundation welcomed

the changes. However AgForce

Queensland criticised the new legislation as a ‘knee-jerk action’ and is concerned that Departmental mapping is ‘wildly inaccurate’.

New South Wales also plans to overhaul its

vegetation management by establishing a new risk-based

framework for clearing native vegetation. The framework proposes to remove

the requirement for a farmer to obtain an approval to clear native vegetation

on their property if it is zoned as exempt or the clearing is carried

out according to a code of practice.

Conservation

groups are concerned that the new

proposals would see a return to broad-scale clearing. However NSW Environment

Minister Mark Speakman indicated

that there would be strong

caps to stop overclearing.

Further reading

Department of Agriculture, Regional Forest Agreements – an overview and history, 2015.

The State of Queensland (Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation)

, Land cover change in Queensland 2012–13 and 2013–14 Statewide Landcover and Trees Study, 2015.

Back to Parliamentary Library Briefing Book

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.