Dr Matthew Thomas, Social Policy and Penny Vandenbroek, Statistics

and Mapping

Key issue

Labour market conditions have generally improved for young people in Australia since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). However, the recovery has been uneven across labour market regions and age groups.

The Government’s main response to youth unemployment is the provision of active labour market programs. Evidence for the effectiveness of these programs is not positive where it comes to disadvantaged young people. Some of the targeted programs introduced in the last two federal budgets have a better prospect of improving participants’ long-term employment outcomes.

Youth employment in Australia

The labour market for young people aged 15 to 24

years deteriorated substantially after the onset of the GFC and has only

recently shown signs of recovery.

However, this recovery has not been uniformly experienced.

Rates of youth participation in the labour market, education and training vary

across the country, with some labour market regions remaining relatively depressed.

Rates of recovery in youth participation have also varied by age.

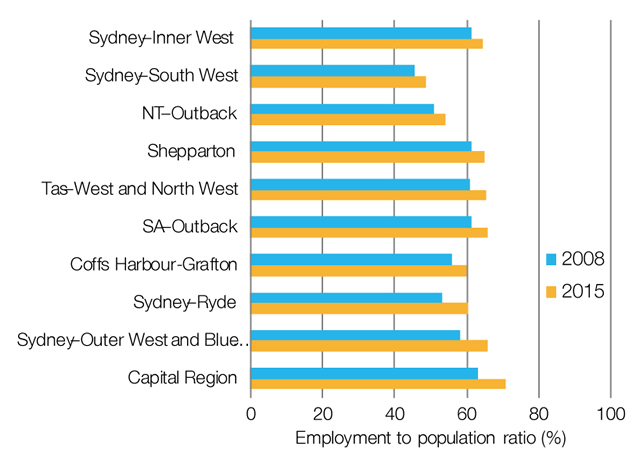

Figure 1 shows the regions with the strongest

positive growth in youth employment (aged 15–24 years), based on the share of population that was employed.

Figure 1:

Growth in youth employment, 2008 and 2015 comparison

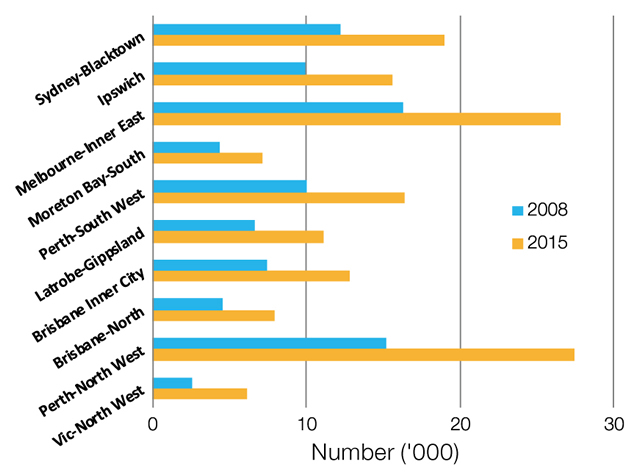

Generally in the youth population, a large portion

of people are neither working nor actively looking for work (i.e. unemployed),

as they are students. Young people opting out of, or exiting the labour force,

is an issue of concern, particularly when they do not go on to undertake some

form of training or other productive activity.

Figure 2 shows the regions that experienced the largest growth in young people who were disengaged from the labour force since 2008.

Figure 2:

Young people not in the labour force, 2008 and 2015 comparison

Measuring youth

engagement

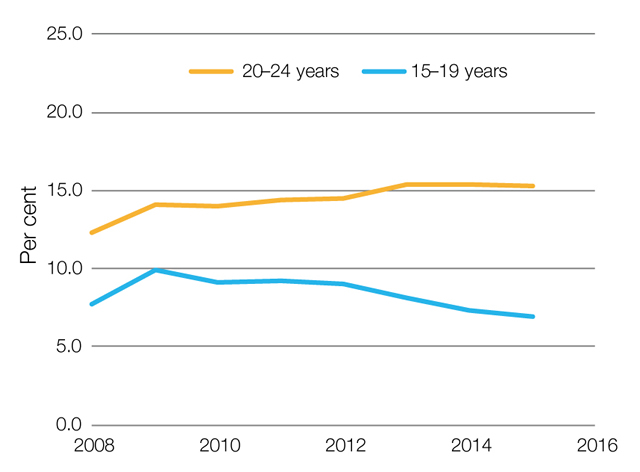

The Not in Education, Employment or Training (NEET)

rate offers a way of analysing those young people who are disengaged, by

expressing them as a proportion of the general working age population (in the

same age group). Labour market statistician Karinne Logez suggests

this type of indicator can provide ‘insight into how well economies manage the

transition between school and work—better than the youth unemployment rate’.

Figure 3 shows a divergence in NEET rates for two

youth cohorts following the GFC.

Figure 3: Level

of engagement in work, study or training (NEET rate)

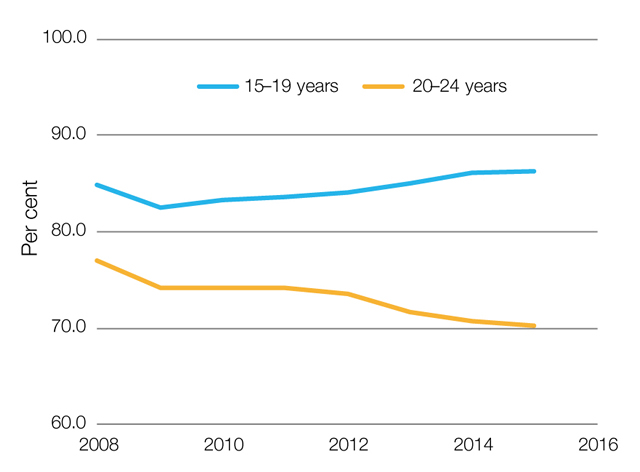

The ‘fully active’ measure is similar to the NEET

rate, but focuses on the positive interactions young people are having with

either work or study. This measure represents young people who are in full-time

education or in full-time work, as a proportion of the civilian population (in

the same age group).

Figure 4 shows the youngest age group has had an

increase in the fully active rate since the GFC, in contrast to those aged 20

to 24 years, who have seen a decline.

Figure 4: Level

of full-time youth participation (in work or study)

Reasons for youth unemployment

In developed countries, young people tend to bear

the brunt of economic downturn, suffering greater job losses and higher

unemployment rates than adults. This is for two main reasons.

Firstly, young people often have little or no

labour market experience, and frequently lack relevant skills. Secondly,

businesses face higher costs of investment and lower costs of termination when

employing young workers.

Combined, these factors contribute to some young

people having a precarious relationship to the labour market. They move between

joblessness, training and working, and are more likely to enter temporary and

insecure employment. In the worst cases, young unemployed people experience

‘scarring’ effects—that is, they suffer from negative labour market experiences

in the future as a result of having been unemployed.

Active labour market programs

Australia has adopted a number of policy responses

to youth unemployment over recent years. These include things like encouraging

and assisting young people to stay in school beyond the age of 16 and tightening

the conditions for eligibility for income support. However, assistance to

unemployed youth through active labour market programs (ALMPs) is the most

common policy response.

Essentially, ALMPs seek to increase the employment

participation of people receiving income support from government, or at risk of

becoming unemployed. In Australia, ALMPs take three main forms, namely job

search; work experience; and formal training and education. These programs are

mostly run by contracted employment service providers through the jobactive system.

There is a large body of international evidence on

the effectiveness of ALMPs, and labour market expert Professor Jeff Borland has

recently compiled a summary

of the Australian evidence.

This evidence—which relates to unemployed people in

general—is mixed where it comes to employment outcomes. There are differences in

the results, both positive and negative, across and within different ALMP

types. The evidence

is similarly varied where it comes to the effectiveness of ALMPs for young

people. One notable exception is public sector job creation programs, such as

Work for the Dole, the evidence for

which is almost universally negative.

What we do know, based on systematic evaluations of the

evidence, is that young people tend to benefit less from ALMP participation

than adults. Further, while ALMPs work reasonably well for people who are

job-ready, they have a limited impact on outcomes for the most disadvantaged jobseekers.

These findings raise questions: what sorts of

intervention, or combination of interventions, do help young people gain

employment? And, in particular, what forms of assistance can deliver results

for young people from disadvantaged backgrounds (for example early school

leavers, young mothers, people with disability, non-English speakers and

Indigenous Australians)?

What policy responses work for young people?

While the overall evidence for the effectiveness of

ALMPs for disadvantaged young people is not positive, the Organisation

for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and

the International

Labour Organisation (ILO) have identified the key

characteristics of those programs that are most likely to achieve successful

labour market outcomes for disadvantaged youth.

The most successful programs directly target disadvantaged

young job seekers, providing a comprehensive package of support services, such

as literacy and remedial education; vocational and job-readiness training; job

search assistance and career guidance and counselling; and social support and workplace

training.

Borland et al. have recently

identified evidence-based elements of best-practice

employment programs for jobseekers with high levels of disadvantage. They argue

that ‘an employment program for jobseekers with high levels of disadvantage

should substantially address their deficiencies in job readiness and skills and

provide a pathway to employment via work experience’. They emphasise that such

programs are most likely to be feasible where they involve collaboration

between service providers and employers at a local level.

Programs like these can pay dividends in terms

of medium- and long-term employment outcomes. However, such programs are costly

and not necessarily highly rated by ALMP evaluations that focus primarily on

short-term employment outcomes.

Recent government initiatives

As a part of the 2015–16

and 2016–17

federal budgets, the Government introduced a number of youth employment

measures that approximate best-practice criteria. The Government has also

reduced the emphasis placed on participation in Work for the Dole. This

strategy to tackle youth unemployment can be seen as being broadly consistent

with both evidence-based

and investment

approaches to social welfare. However, evidence for the effectiveness of the

Government’s proposed four-week

waiting period for income support for under 25 year olds is questionable.

It is also not clear that the Government’s central proposal to

address youth unemployment—through the Youth Jobs PaTH program—will gain

sufficient support from employers, or provide adequate assistance to job

seekers to produce meaningful results. Much will depend on the level of

economic activity over coming years, the boosting of which is the best means to

ensure increased levels of youth employment.

Further reading

J Skattebol, T Hill, A Griffiths and M Wong, Unpacking youth unemployment, Social policy Research Centre, University of New South Wales, Sydney, September 2015.

J Stanwick, Tham Lu, T Rittie and M Circelli, How young people are faring in the transition from school to work, Foundation for Young Australians, September 2014.

H Cuevo and J Wyn, Rethinking youth transitions in Australia: A historical and multidimensional approach, Research report no. 33, Youth Research Centre, University of Melbourne, 2011.

L Denny and B Churchill, ‘Youth employment in Australia: a comparative analysis of labour force participation by age group’, Journal of Applied Youth Studies, 2, 2016, pp. 5–22.

Back to Parliamentary Library Briefing Book

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.