Posted 03/04/2017 by Renee Westra

Almost three years after the first US operations against the Islamic State commenced in Iraq, the US footprint in Iraq and Syria continues to grow, though the contributions of its allies largely remain static. There are now in excess of 5,000 US troops deployed in Iraq, and close to 1,000 in Syria. Reportedly, the Trump Administration is also set to abolish the troop caps officially set by the Obama Administration (5,000 in Iraq and 500 in Syria), enabling even larger deployments. Contractor support—not reflected in any official figures—could also add to this number. As at 28 March, the US had conducted 15,258 air strikes in Iraq and Syria, three quarters of the total coalition effort, with the operational tempo steadily increasing. In advance of the assault on Raqqa, select opposition groups in Syria have also received a substantial increase in both equipment and non-combat support. As at February 2017, these operations have cost US$11.7 billion.

Clearly, this is a substantial commitment and boots are already on the ground, though the Pentagon continues to insist these are not combat troops, describing them instead as operating within ‘train and equip’, ‘advise and assist’ and ‘reassure and deter’ missions. While these troops do not technically ‘initiate’ combat, what these missions entail appears fairly flexible. US troops involved in these technically non-combat missions have given their military partners front-line assistance, provided tactical air lift, called in air strikes and given artillery support. So at what phase of operations are boots considered to be on the ground or a nation to be fully engaged in a conflict, especially without any clear articulation of an end point or longer-term plan? This is an important question given the US ultimately determines the overall trajectory of the coalition campaign.

Despite its growing investment, the Trump Administration has released few public details on the broad mission parameters or intended end-state of US activity in Iraq and Syria. However, on 30 March, US Secretary of State Tillerson announced that ‘the status of President Bashar al-Assad would be decided by the Syrian people’. This effectively confirms the Islamic State fight as the top priority for the US and the subordination of other issues to this goal, such as leadership change. Thus far, media speculation about initiatives has included additional troops in Syria, increased support for the Kurds ahead of the fight for Raqqa, and creating safe zones. Developments on the ground indicate at least some of these things are already happening.

Additionally, there are indications that the level of public information previously available on these operations will be scaled back. The US Central Command spokesman told reporters earlier this week that the exact number of troops will no longer be available; instead ‘it will be about capabilities not numbers’. This is a significant departure from the Obama Administration’s focus on troop numbers as an element of policy-making and public outreach, and raises questions about how growing participation in the conflict will be managed or publicly explained.

While there is an indisputable need to maintain a certain level of secrecy when it comes to military operations, there is a significant level of public interest in allowing open discussion about these developments—especially given that US operations are occurring in areas where an end-state has not been clearly articulated, the potential for long-term entanglement is high and the legal basis for action is contested.

And Australia?

The apparent trajectory and purpose of future US operations in Iraq and Syria clearly raises questions for coalition partners and allies who may be expected to do more in support of the Trump Administration’s objectives. This includes Australia, which has 780 personnel deployed to the Middle East, split across training missions in Iraq and the Syria/Iraq Air Task Group.

Following the March Counter-Islamic State Coalition meeting, Foreign Minister Julie Bishop reportedly said no ‘specific’ requests had been made of Australia to contribute more to the campaign, but that the government would consider extra assistance if asked. She also said that the Trump Administration had conveyed its interest in intensifying the military campaign against the Islamic State, identifying Syria as the next phase in the battle. Despite the absence of any Australian policy or comment on these changes, the Australian Government has been consistent in emphasising that ‘there will be no peace in Iraq without political reconciliation or in Syria without a political solution’.

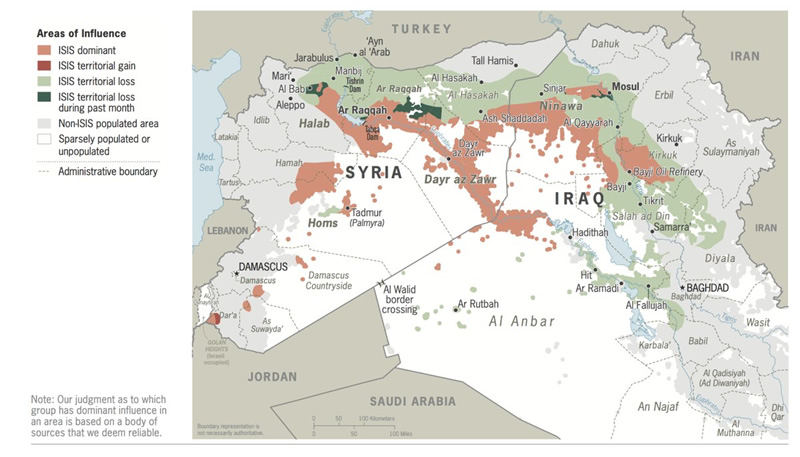

Less clear is the US commitment to a political solution or political reconciliation under President Trump. What we do know is that reconstruction, long-term development, and state-building—arguably an intrinsic part of a political solution—do not appear to be on the US agenda. In a twisted sense, the Islamic State—as a common enemy—is a unifying factor which arguably keeps groups in the region from fighting each other (see the complexity of the environment in the map below). However, the US’s increasingly singular focus on removing the Islamic State could lead to a scenario in which further conflict is created, especially if underlying political issues are not addressed. Not least among these problems is the prospect of recreating a permissive environment for Islamic State support to re-emerge, a scenario which the group has already twice proven it is able to exploit.

Areas of influence: end February 2017 (source: Global Coalition)