Posted 29/01/2014 by Hannah Gobbett

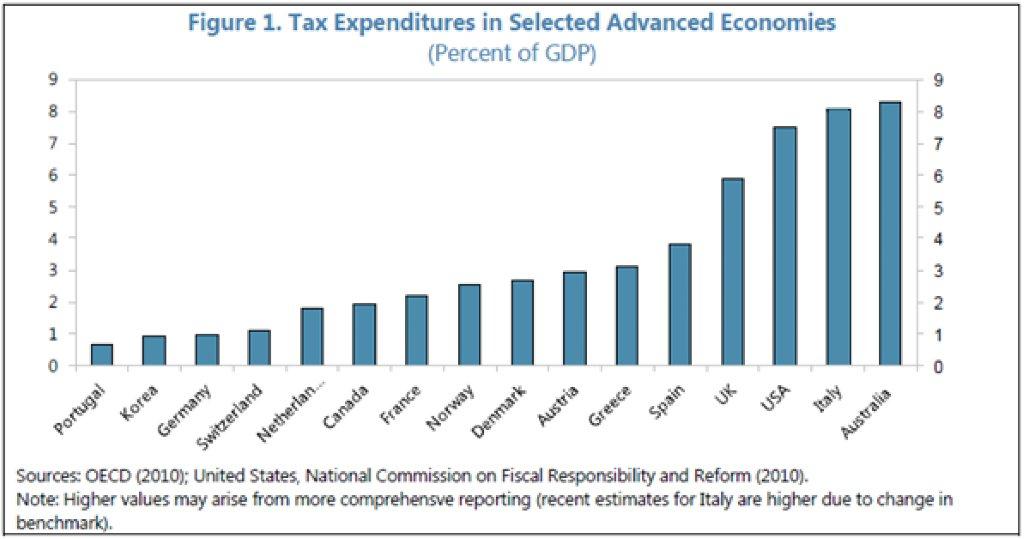

In the International Monetary Fund (IMF)’s recently released ‘Reforming Tax Expenditures in Italy: What, Why, and How?’, Australia was found to forgo more revenue as a proportion of GDP than all other OECD nations.

Although tax expenditures result in the government forgoing revenue, they have not been widely scrutinized and cannot be comprehensively measured. As a method through which specific groups, sectors, regions and activities receive a ‘myriad of discounts in the tax code’, tax expenditures continually arise as the subject of debate.

When the Government exempts an activity from tax, it has the same effect on the budget as if the Government had given a direct subsidy to that activity. A benefit that is provided in this way is called a tax expenditure. Such benefits include tax exemptions, tax deductions, tax offsets, concessional tax rates and deferrals of tax liability.

Tax expenditures are reported in an annual statement by Treasury. In 2012–13, there were 363 tax expenditures provided under the Australian tax system, the total value of which was estimated at approximately $115 billion, or 7.5% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). For comparison, total government direct spending in 2012–13 was about 23.5% of GDP. However, uncertainty about the incidence of tax expenditures means the valuation is only an estimate. Note that negative gearing, the private health insurance rebate, and family tax benefit are not counted as tax expenditures in the Treasury tax expenditures statement.

All developed nations have tax expenditures, and they are difficult to compare because what is classified as a ‘tax expenditure’ in one nation may not be in another. In the US in 2012 the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) estimated that the US government had 169 different tax expenditures resulting in $1 trillion of tax revenue foregone. As the graph demonstrates, Australia forgoes a comparatively large proportion of GDP in tax expenditures.

Source: International Monetary Fund, 2013

Tax expenditures are intended to achieve policy objectives of the Government. They are essentially the same as government spending programs, but because they are administered through the taxation system, tax expenditures do not require annual appropriation bills. The Henry Review of Australia’s tax system observed that tax expenditures are less transparent and accountable than program measures, they are not subject to routine evaluation and usually there is no ‘sunset’ provision. Significant items which Treasury cannot quantify are also not included in these evaluations, such as the income tax exemption for charitable, religious, scientific and community organisations.

Because Australia has a progressive tax system—the marginal rate of tax gets higher as income goes up—most tax expenditures deliver a higher rate of subsidy to the more affluent. The goods and services tax (GST) is levied at a single rate, so on the face of it an exemption should affect everyone equally. However, education, health and financial services are ‘superior’ goods: people spend a greater proportion of their income on them as their income rises. More affluent people, therefore, gain more from the exemption of these services from the GST.

Further, tax expenditures are often granted as a result of lobbying, and due to their lack of transparency, are often seen as unfair. Richard Krever argues that tax expenditures invite abuse and restructuring of income to take advantage of them, in turn stimulating anti-avoidance measures and further gaming of new rules.

The outcomes of tax expenditures are difficult to predict or to measure. Comprehensive data does not exist and evaluations cannot be made, so it is hard to know if a tax expenditure has reached its target group. It also cannot be known whether it has changed behaviour—for example, increasing saving for retirement—or has simply been a windfall to people who were going to save anyway.

There is rarely an evaluation of whether a tax expenditure is the best way to achieve an outcome. Tax expenditures receive less scrutiny and, more often than not, make the taxation system more complicated. If the Government’s policy is to increase the amount of educational services people consume, measures targeted to individuals and groups who are seen as under-consuming education might be preferable to a universal GST exemption.

The IMF recommends regular and systematic review of tax expenditures similar to the regular review of government expenditures, and an annual reviewing process by Parliament. ‘An added benefit would be a simpler tax system that reduces administration costs and strengthens compliance.’

The current National Commission of Audit, in its Terms of Reference is committed to ‘identify areas of unnecessary duplication between the activities of the Commonwealth and other levels of government; identify areas or programs where Commonwealth involvement is inappropriate, no longer needed, or blurs lines of accountability; and improve the overall efficiency and effectiveness with which government services and policy advice are delivered.’ Although tax expenditures were not explicitly mentioned, the Business Council of Australia has called for tax expenditures to be included as they ‘comprise a far more significant cost to government and must be considered in any comprehensive (spending) review’.

Please note that the IMF and this Flagpost used data from the Tax Expenditures Statement 2012. The Tax Expenditures Statement 2013 was released after this Flagpost was first published.