19 April 2023

PDF version [843 KB]

Dr Shannon Clark

Social Policy Section

Executive

summary

School refusal is a type of school

attendance problem characterised by a child or young person’s emotional

distress at attending school.[1]

It differs from other forms of school attendance problems in terms of the

distress experienced, and in that parents and carers typically know about their

child’s absence from school and have tried to get them to attend.[2]

This distinguishes school refusal from truancy (where

parents or carers are often unaware of their child’s absence), school

withdrawal (where parents may support or encourage their child to stay home),

and school exclusion (which stems from school-based decisions).[3]

Estimates of the prevalence of school refusal in Australian

and international literature are between 1% to 5% of all students.[4]

Its prevalence is higher among students with autism spectrum disorders and

attention‑deficit/hyperactivity disorder.[5]

Across the world, there have been reports of growing rates of school refusal

following the COVID-19 pandemic.[6]

In Australia, school staff, parents and support services report that the

incidence of school refusal has increased following COVID-19 school

disruptions.[7]

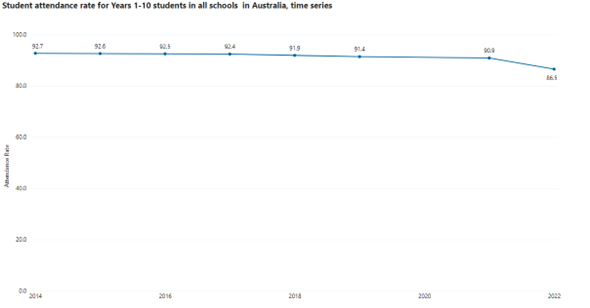

In Australia, school attendance has been trending

downwards over a number of years and there was a marked decrease in 2022.[8]

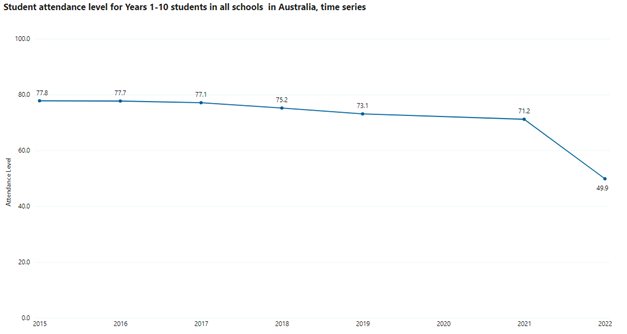

In 2022 in Australian schools, the student attendance rate—the percentage of

possible days that students in Years 1–10 attend school—was 86.5% while the

attendance level—the proportion of students in Years 1–10 whose attendance rate

is equal to or greater than 90%—was 49.9%. This is a sizeable drop from 2021,

when the attendance rate was 90.9% and the attendance level was 71.2%. These

measures do not identify different reasons for non-attendance. In international

literature, missing 10% or more of available school days is a common cut-off

point for chronic absenteeism.[9]

A number of complex factors can contribute to school

refusal. These include stressful life events, problems at school with peers or

a teacher, academic difficulties, bullying, illness, and transitions such as

starting or moving school.[10]

Young people with school refusal are often diagnosed with anxiety disorders.[11]

School refusal can negatively impact students’ learning

and achievement and place them at risk of leaving school early.[12]

School refusal can also have longer term impacts on children and young people’s

social and emotional development and mental health into adulthood.[13]

Dealing with a child or young person’s school refusal can be a source of stress

and conflict for families.[14]

Contents

Executive

summary

Introduction

What is school refusal?

Prevalence

School attendance in Australia

Drivers of school refusal

Consequences of long-term infrequent

school attendance

Addressing school refusal and

absenteeism

Conclusion

Additional

resources

Introduction

Following disruptions to schooling from the COVID-19

pandemic, there have been increasing concerns about the rising incidence of school

refusal among Australian students.[15]

School refusal is characterised by a child or young person experiencing significant

emotional distress at the idea of going to, or staying at, school.[16]

As well as being distressing for the child or young person themselves, it is

also stressful and disruptive for families, teachers and school staff.

This paper discusses school refusal and how it differs from

other types of school attendance problems drawing on international and

Australian literature. It considers its prevalence, as well as the national

data on school attendance available in Australia. School refusal is a complex

and multifaceted problem that can occur for a range of different reasons.

Different factors that can contribute to school refusal are discussed as well

as approaches to address school refusal and absenteeism. Finally, the paper considers

the impacts of school refusal on children and young people in the short term

and longer term, as well as impacts on the classroom more broadly.

What is school refusal?

School refusal is a type of school attendance problem based

on a student’s emotional distress at attending school.[17] Although there are variations

in definitions, features of school refusal include:

-

reluctance or refusal to attend school, often resulting in

extended school non-attendance (some definitions include absence thresholds)

-

severe emotional upset, which can take various forms, including

fear, anxiety, depression, anger, determined resistance, somatic health

complaints (such as headaches, stomach aches), and sleep disturbance

-

staying at home with parents’ or carers’ knowledge

-

parental attempts to secure their child’s attendance at school

-

absence of significant anti-social disorders.[18]

These features distinguish school refusal from other types

of school attendance problems, such as:

- truancy, whereby children and young people are absent from

school or class without permission, they generally conceal their absences from

their parents, and may show antisocial behaviours

- school withdrawal, whereby absenteeism is mainly motivated

by parent factors, with parents not attempting to get their child to attend

school, or encouraging them not to attend

- school exclusion, which is problematic absenteeism

stemming from school-based decisions, for example, relating to disciplinary

measures, resource allocation, or for school-based performance requirements.[19]

There can be overlaps between the types of school attendance

problems, and children and young people may experience different types of

absenteeism at different times.

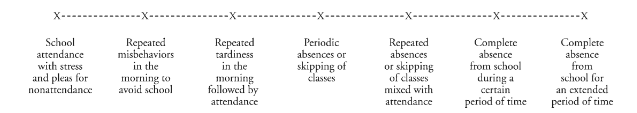

There is a spectrum of school refusal behaviour, reflecting

different levels and kinds of absenteeism (Figure 1):

Figure 1 Spectrum

of school refusal behaviour

Source:

Christopher Kearney, Helping School Refusing Children and

Their Parents: A Guide for School-Based Professionals, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), 8.

School refusal typically develops along a continuum, with

different expressions over time.[20]

Early identification and intervention is crucial, as the more school a student

misses, the harder it is to return to school and the more likely it will be

that they will stay out of school entirely.[21]

School refusal is also sometimes referred to, or used

interchangeably with, terms including ‘School Can’t’, problematic absenteeism,

school avoidance, school reluctance, school phobia and emotion(ally) based

school avoidance (EBSA).[22]

Prevalence

Estimates of the prevalence of school refusal cited in

Australian and international literature are generally between 1% to 5% of all

students.[23]

However, there are difficulties capturing school refusal data given the range

of school refusal behaviours (for example, somatic symptoms, lateness, partial

or complete absences), as well as different definitions and different ways of

tracking school absences.[24]

School refusal can occur throughout the range of school

years; however, there tend to be peaks around certain ages (usually between 5–6

years and 10–11 years) and transitions (such as starting primary school or high

school, or moving schools).[25]

Students with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are at higher risk of school

refusal. For example, a study of students in the UK with ASD found that 43% of

students had persistent non-attendance (absent for more than 10% of available

sessions), and that school refusal accounted for 43% of non-attendance.[26] An Australian study

examined reasons for school non-attendance for children on the autism spectrum

and found that 72.6% of responders had persistent absences (3 or more days in a

20-day period), with school reluctance/refusal responsible for the highest

number of half and full days missed in total.[27]

Increased school refusal and the COVID-19 pandemic

Schools, parents and those treating students, such as

psychologists and social workers, report that there have been increases in the

prevalence of school refusal in Australia following disruptions to schooling

due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[28]

For example:

Bayside School Refusal Clinic director John Chellew said he

had noticed a "significant increase" in referrals since the COVID-19

lockdowns in Melbourne last year.

"Statistics were saying between 2 and 5 per cent of

children, up until last year, were school refusing. That then doubled last

year," Mr Chellew said.

"Anecdotally, now we are thinking about the statistics

trebling."[29]

Trends of increasing school refusal following the COVID-19

pandemic have also been reported in other countries.[30]

For example, a short report published by the United Kingdom Office for

Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills (Ofsted) in February

2022 examined aspects of school attendance and how schools approach challenges

of persistent absence.[31]

The report noted that many schools were experiencing higher than average

absences due to COVID-19, both directly—for example, due to student illness—and

indirectly—for example, due to parents’ and students’ anxieties. Successive

national lockdowns had contributed to social anxiety for some.[32]

On 27 October 2022, the Australian Senate referred the issue

of the national trend of school refusal and related matters to the Education

and Employment References Committee for inquiry and report.[33]

Following an extension of the Committee’s reporting date, the Committee is due

to report by 21 June 2023.[34]

School

attendance in Australia

In Australia, school attendance is compulsory, typically

from the age of 5–6 until age 17.[35]

State and territory legislation sets out age ranges for compulsory schooling,

as well as attendance requirements for students of compulsory school age.

School attendance for Australian students in Years 1–10 is

reported by the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority

(ACARA) via the National

Report on Schooling in Australia—Data Portal. The Key Performance Measures

(KPMs) for attendance, as specified in the Measurement Framework

for Schooling in Australia, are ‘attendance rate’ and ‘attendance

level’:

Key Performance Measure 1(b) Attendance rate. The

number of actual full-time equivalent student-days attended by full-time

students in Years 1-10 in Semester 1 as a percentage of the total number of

possible student-days attended in Semester 1.

Key Performance Measure 1(c) Attendance level. The

proportion of full time students in Years 1-10 whose attendance rate in

Semester 1 is equal to or greater than 90 per cent.[36]

The measures do not differentiate reasons for

non-attendance. Furthermore, these figures do not include the number of ‘detached

students’, young people of compulsory school age who are not enrolled in a

formal education program of any type. A 2019 report estimated conservatively

that the number of detached students across Australia was 50,000.[37]

Chronic absenteeism occurs when students miss too much

school.[38]

A common cut-off point in international literature for chronic absenteeism is

10%; that is, students with attendance rates below 90% for any reason are

considered as chronically absent.[39]

In Australia, this equates to approximately 20 or more days absent in a year.[40] The KPMs reflect

this cut-off.

In 2022 in Australian schools, the student attendance rate

was 86.5% while the attendance level was 49.9%.[41]

This is a sizeable drop from 2021, when the attendance rate was 90.9% and the

attendance level was 71.2%. Attendance data for 2020 was not published due to

inconsistencies in the data relating to the COVID-19 pandemic.

ACARA’s data portal notes that:

Attendance rates in Semester 1 2022 declined due to the

impact of the COVID-19 Omicron variant and high Influenza season outbreaks and

floods in certain regions experienced across Australia at that time.[42]

The following figures show time series student attendance

rates and attendance levels from 2014 and 2015 to 2022.

Figure 2 Student attendance rate for Years 1–10

students in all schools in Australia, time series

Source:

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA), ‘Student Attendance’, National Report on Schooling in

Australia—Data Portal, Time Series.

Figure 3 Student attendance level for Years 1–10

students in all schools in Australia, time series

Source: ACARA,

‘Student Attendance’, National Report on Schooling in

Australia—Data Portal, Time Series.

Attendance

trends

Attendance tends to vary across years of schooling,

with schools experiencing a drop in attendance as students advance through the

years from Year 3 to Year 10.[43]

The biggest drops occur between years 7 and 10. In 2022:

-

the attendance rate was 87.3% for Year 7 students, falling to

82.9% for Year 10 students

-

the attendance level was 52.7% for Year 7 students, falling to

41.6% for Year 10 students.[44]

Attendance also differs by location, with school

attendance declining as geographical remoteness increases.[45] In 2022:

-

the attendance rate for students in Years 1–10 in major cities

was 87.5% compared with 63.1% in very remote areas

-

the attendance level for students in Years 1–10 in major cities

was 52.4% compared with only 19.7% for students in very remote areas.[46]

There is also a gap in school attendance between Indigenous

and non-Indigenous students in Australia.[47]

In 2022:

-

the attendance rate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

students across Australia was 74.5% compared with 87.4% for non-Indigenous

students

-

the attendance level for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

students was 26.6% compared with 51.5% for non-Indigenous students.[48]

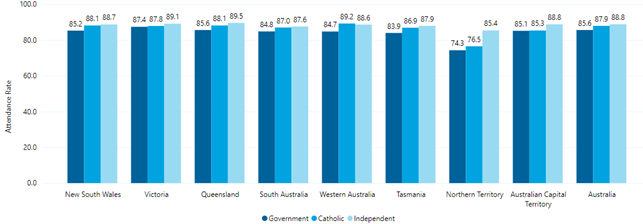

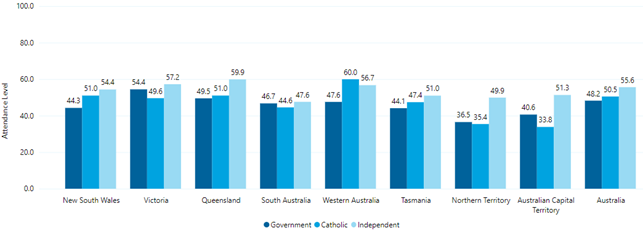

There are also differences in school attendance across

Australia by school sector, with independent schools tending to have the

highest attendance rates and levels and government schools the lowest. In 2022

for students in Years 1–10:

- government schools had an attendance rate of 85.6% and an

attendance level of 48.2%

-

Catholic schools had an attendance rate of 87.9% and an

attendance level of 50.5%

-

independent schools had an attendance rate of 88.8% and an

attendance level of 55.6%.[49]

However, there is variation across the states and

territories (see Figures 4 and 5). For example, in 2022 for students in Years

1–10:

-

the attendance level for Catholic schools in WA (60.0%) was the

highest of the sectors while it was the lowest of the sectors in the ACT

(33.8%) and NT (35.4%)

-

the attendance level for government schools in Victoria (54.4%)

was the second highest of the sectors in the state and 10.1 percentage points

higher than government schools in NSW (with a larger gap for ACT and NT government

schools).

Figure 4 Student attendance rate by state/territory for

Years 1–10, 2022

Source: ACARA,

‘Student Attendance’, National Report on Schooling in

Australia—Data Portal, School Sector by State/Territory.

Figure 5 Student attendance level by state/territory

for Years 1–10, 2022

Source: ACARA, ‘Student Attendance’, National Report on Schooling in

Australia—Data Portal, School Sector by State/Territory.

Drivers of

school refusal

School refusal is complex and multifactorial. It is

associated with a range of risk factors, including individual traits,

socio-economic conditions, family structure, the school environment and society

more broadly. Factors that can contribute to school refusal include:

-

stressful life events

-

major transitions such as starting primary or secondary school

-

moving or other big change

-

fear of harm coming to a parent

-

illness in the family

-

separation and divorce

-

academic problems

- overprotective parenting

-

friendship difficulties

-

separation anxiety.[50]

There are different conceptualisations of school refusal.

For example, school refusal can be understood as a symptom of an underlying

mental illness or disorder. Young people exhibiting school refusal are often

diagnosed with anxiety disorders, such as generalised anxiety disorder,

separation anxiety disorder, panic disorders and/or social anxiety, with 50% to

80% of children or young people with school refusal meeting criteria for one or

more such disorders.[51]

School refusal has also been characterised in terms of

underlying motivations. For example, school refusal can be understood as being

driven by negative reinforcement whereby students avoid situations that prompt

unpleasant or anxious feelings (such as separation from caregivers, social

interactions or academic requirements like a test or presentation), or aversive

situations (such as bullying).[52]

On the other hand, school refusal can also be understood as being driven by

positive reinforcement, whereby students are motivated to stay home to get

attention from parents, or to do activities at home that they find more

enjoyable, such as watching television, social media or sleeping. School

refusal can be motivated by a mixture of both positive and negative

reinforcement.[53]

A criticism of bio-medical models is that they tend to

locate school refusal and distress as problems with individual students and

families and can reinforce negative stereotypes and deficit perceptions.[54] Increasingly, the

importance of factors relating to young people’s life experiences and school

factors are being recognised, with school refusal seen ‘as signals that all is

not well in the young person’s world’.[55]

Research literature often groups drivers or risk factors for

school attendance/absence into 4 domains: the individual, the family, the

school and the broader community. A summary of these groupings as outlined in Problematic

School Absenteeism—Improving Systems and Tools (a collaborative Nordic

project funded by the European Union’s Erasmus+) is provided below:

Individual factors

-

psychological problems, for example, anxiety or depression

-

developmental disorders, such as ASD or ADHD

-

physical health, such as chronic illness

-

substance abuse

- (undetected) learning disabilities.

Family factors

-

family structure, functioning and parenting style

-

socio-economic disadvantage

-

parental physical or mental health problems

-

low parental involvement in schooling

-

overprotective parenting style.

School factors

-

poor classroom management, for example, lack of classroom order

and poor structuring of instruction and/or of social interactions between

students

-

failure to prevent or manage bullying, social isolation,

unpredictability at school

- school transitions, for example, due to changes between schools,

starting a new school year or returning after a holiday period

-

changes in pedagogical practices, for example, going from one

primary teacher to subject‑specific teaching.

Community factors

- society-wide pressure on students to achieve academically

- perceptions of threats, such as school shootings or terrorism

-

neighbourhood characteristics, such as poverty, and structural

barriers, such as lack of transport infrastructure or living in remote

locations.[56]

Consequences of long-term infrequent school attendance

Schools are important for students’ development socially and

academically. As such, school absences can have short and long-term negative

impacts on children and young people’s essential competencies, including

socio-emotional competences, and literacy and numeracy skills.[57]

Without treatment, school refusal can have negative impacts

on students’ learning and achievement, as well as placing these students at

risk of dropping out of school early.[58]

Students refusing school are also more likely to experience problems in social

adjustment and to have ongoing mental health problems in late adolescence and

adulthood.[59]

The crisis-like presentation of school refusal can cause

distress for parents and family conflict as they manage the challenge.[60] School refusal

may also negatively impact on teaching and school staff due to stress and

uncertainty in how to manage the problem and in strained relationships with

families.[61]

International literature has also highlighted negative

effects associated with school non‑attendance over the longer term. For

example, various forms of school attendance problems have been associated with

poor health outcomes, marital and psychiatric problems, non-violent crime and

substance use, and occupational problems and economic deprivation later in life.[62]

Impact of school absences on academic performance

A report commissioned by the Australian Government

Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR) in 2012 examined

the relationship between school attendance and students’ academic performance.

The study used data collected about students in government schools in Western

Australia, including attendance records and results from the National

Assessment Program—Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN). It found:

average academic achievement on NAPLAN tests declined with

any absence from school and continued to decline as absence rates increased.

The nature of the relationship between absence from school and achievement, across

all sub-groups of students strongly suggests that every day of attendance in

school contributes towards a child’s learning, and that academic outcomes are

enhanced by maximising attendance in school. There is no “safe” threshold.[63]

The report noted that the effects of absences accumulate

over time.

The study found that unauthorised absences (absences that

are unexplained or where the reason is not deemed acceptable by the school principal)

had a significantly stronger association with achievement than authorised

absences (absences for which a legitimate reason for the absence is given, such

as illness), with even small amounts of unauthorised absence associated with

substantial falls in average NAPLAN test scores. The authors suggested that

unauthorised absences could reflect possible behavioural and school engagement

issues, rather than just time away from school.[64]

The report observed some students were more adversely

affected by absences than others, with gaps in achievement evident for students

depending on where they live, their socio-economic status, and Indigenous

status at all levels of attendance.[65]

More advantaged students had relatively high levels of achievement irrespective

of their levels of school attendance.[66]

Impact of school refusal on the classroom

The negative impacts of school absenteeism and school

refusal are predominantly discussed in terms of impacts on the child or young

person themselves. However, school refusal and chronic absenteeism can have

spillover effects on other students’ academic achievement and can negatively

affect teachers and school staff. This section discusses secondary impacts of

school refusal and chronic absenteeism.

Chronic absenteeism not only affects the student who misses

school but can potentially reduce outcomes for classmates. A study of student

results from an urban elementary school in the US examined the spillover

effects of chronic absenteeism on classmates’ achievement.[67] The author hypothesised that

extreme rates of absenteeism could slow the regular pace of classroom

instruction as highly absent students would require significant remediation

efforts and classroom management efforts from teachers when returning to class.

The study found evidence that having a greater proportion of chronically absent

classmates was associated with lower achievement across reading and

mathematics.

School refusal can cause stress for teachers and school

staff and can have a negative impact on relationships between teachers and

students and families. Teachers and principals interviewed as part of a

qualitative study from Ireland reported feeling responsible for assisting

students who had been absent to catch up, which took time away from other

students in the class.[68]

Teachers felt stress and frustration at the disruption to class dynamics of

students returning and pressure to see students complete project components or

examinations.

Cases of school refusal may also require school staff to

liaise with a diverse array of support services, such as child protection and

family support services, social work and psychological services.[69] This can be a

source of stress as participants negotiate what the role and duty of schools

should be, and what should be the responsibility of other services and

providers.[70]

Addressing school refusal and absenteeism

Given the complex nature of school refusal, approaches aimed

at assisting children and young people to return to school need to be

multilayered and flexible.[71]

Identifying the factors contributing to a student’s school refusal is important

for determining the resources that might be employed to address the problem.

The resources that are available to a child or young person

to address school refusal may not be equally accessible. Although school

refusal cuts across social class divides, families with ‘greater social,

cultural, financial capital tend to have the necessary resources to manage the

situation and ensure a positive outcome’.[72]

Families from higher socio-economic backgrounds may have more choice in

accessing assessment services and therapeutic supports.[73]

Federalism may also pose complications for developing

national approaches to school refusal in Australia. States and territories have

overarching responsibility for schools in their jurisdictions. While the Australian

Government plays a role in providing funding for schools and participating

in national policy decisions with states and territories, it does not own or

manage any schools.[74]

This section discusses multitiered approaches to addressing

school attendance and briefly considers the (in)effectiveness of punitive

approaches.

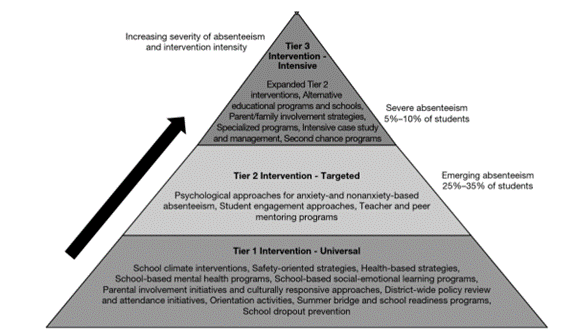

Multitiered

approach to absenteeism

Many resources on addressing school refusal and student

absenteeism advocate for a multitiered approach.[75] Christopher Kearney’s 2016

book, Managing School

Absenteeism at Multiple Tiers: An Evidence-Based and Practical Guide for

Professionals, outlines strategies for addressing problematic

absenteeism organised into 3 tiers (see Figure 6 below). The tiers represent

increasing severity of absenteeism and intervention:

-

Tier 1: universal prevention—approaches focus on functioning and

school-wide attendance and on preventing absenteeism for all students

-

Tier 2: targeted early intervention—approaches focus on

addressing students with emerging, acute, or mild to moderate school

absenteeism

-

Tier 3: intensive later intervention—approaches focus on

addressing students with chronic and severe school absenteeism.

Figure 6 A

multitier model for problematic school absenteeism

Source:

Christopher Kearney, Managing School Absenteeism at Multiple Tiers: An

Evidence-Based and Practical Guide for Professionals, (New York: Oxford

University Press, 2016), 16.

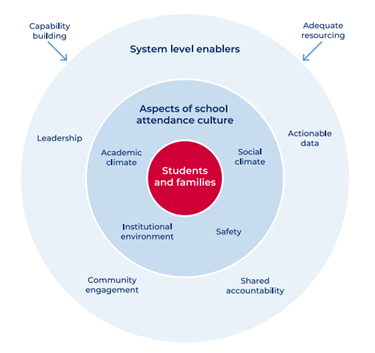

Implementing strategies to improve attendance requires

adequate resourcing and system supports (see Figure 7).

Figure 7 Enablers

for implementing strategies to improve attendance and establish a positive

attendance culture in schools

Source: CESE, Understanding Attendance, 36.

Recent media articles on school refusal have reported the

challenges schools face in managing students refusing school, including

shortages of specialist knowledge, allied health, and psychological and

counselling services.[76] For example,

media articles have reported shortages of school counsellors and psychologists

in schools, such as an October 2022 report in The

Guardian of a ‘dire shortage’ of school counsellors in NSW, with

figures obtained showing that there was one counsellor for every 650 students

across the state.[77]

The Australian Psychological Society’s framework

for the provision of effective psychological services in schools recommends

a ratio of one psychologist to 500 students, based on data from United Nations

countries and best practice.[78]

The 2021 Gallop inquiry, commissioned by the NSW Teachers Federation,

recommended providing school counsellors:

on the basis of at least 1:500 students and a corresponding

increase in senior psychologists [sic] education by 2023 to address the

significant increase in student mental health issues[79]

Punitive

approaches

Research does not indicate that punitive approaches to

school attendance are effective in improving attendance as they do not address

the root cause of attendance problems.[80]

As school attendance is compulsory in Australia, not attending school can

result in legal penalties for families, and/or the possible involvement of

child protection services.[81]

However, there is no evidence to suggest that fines or court orders improve attendance

for individual students.[82]

At the family level, some have argued for parents to employ a

stricter disciplinary approach to dealing with their child’s school refusal.

For example, Victorian Shadow Minister for Education Matthew Bach stated in an

opinion piece:

School refusal stems from anxiety, which – as we know – is a

serious mental health condition. And because of this, parents naturally

empathise deeply with their children. Yet what the growing number of children

who refuse to attend school need most is tough love. Going to school must

simply be non‑negotiable.[83]

However, authoritarian approaches can negatively impact children

refusing to go to school.[84]

Negative family processes, including intrusive and constraining parental control

and harsh and corporal punishment, increase the likelihood of school

absenteeism and dropout, while positive family processes, including parental

support and monitoring, acceptance, clear boundaries and granting of autonomy decrease

the likelihood of school absenteeism and dropout.[85]

As such, interventions aimed at increasing positive family process,

particularly in primary school, and decreasing negative family processes,

particularly in secondary school, may be beneficial to address school absenteeism.[86]

Conclusion

COVID-19 caused massive social disruptions across the world.

In Australia, governments and school systems responded to the unfolding

pandemic by introducing measures such as school closures, pupil free days, remote

learning, and relaxing attendance requirements.[87]

In addition to the pandemic, many students across Australia have been impacted in

the last few years by natural disasters, including bushfires and floods. These

situations have created contexts rich in the risk factors identified as

contributing to school refusal, such as stressful life events or big changes,

school transitions, family illness or fear of harm coming to a parent, and friendship

difficulties.

While there are increasing concerns about the rising incidence

of school refusal, there are challenges in understanding the extent of the

problem. Across Australia, the national attendance rate and attendance level

have been trending downwards for a number of years, with a particularly

noticeable decline in both measures in 2022. In 2022, less than half of

students attended school for 90% or more of available school days in Semester

1. Put another way, more than half of students across Australia were

chronically absent from school in 2022. The national data also show differences

in attendance according to years of schooling, geography, indigeneity, and

school sectors. There is also substantial variation across the states and

territories in terms of attendance. While these figures do not provide insight

into the reasons for school non-attendance, such as school refusal, they do

point to wider problems of absenteeism.

Greater understanding of the reasons for student absenteeism

may allow school communities to better address the needs of students who are

refusing school, or who are otherwise disengaged or at risk of disengaging. At

a broader level, research into the reasons for variation between the states and

territories may also shed light on factors contributing to higher or lower school

attendance. In February 2023, Education Ministers commissioned the Australian

Education Research Organisation to investigate the causes of declining

attendance and provide advice to Ministers on evidence-based approaches that

support attendance.[88]

It will also be vital to ensure that schools have the resources available to

assist students’ return to the classroom, to support student wellbeing and

mental health, and to ensure that there are avenues to enable students to

continue to learn.

Additional resources

The following additional resources provide useful information about school refusal, school absences and management strategies:

|

[1]. Julia Martin

Burch, ‘School

Refusal: When a Child Won’t Go to School’, Harvard Health Publishing

(blog), 18 September 2018.

[2]. For example,

see David Heyne et al., ‘Differentiation

between School Attendance Problems: Why and How?’, Cognitive and Behavioural Practice

26, no. 1 (February 2019): 8–34.

[3]. Murray Evely

and Zoe Ganim, School

Refusal (Revised), excerpt, Psych4Schools, n.d.

[4]. Jill Sewell, ‘School Refusal’, Australian

Family Physician 37, no. 4 (April 2008): 406–408; Trude Havik and Jo Magne

Ingul, ‘How

to Understand School Refusal’, Frontiers in Education 6, no. 715177

(September 2021).

[5].

Vasiliki Totsika et al., ‘Types and Correlates

of School Non-attendance in Students with Autism Spectrum Disorders’, Autism

27, no. 7 (October 2020): 1639–49; Dawn Adams, ‘Child and

Parental Mental Health as Correlates of School Non-attendance and School

Refusal in Children on the Autism Spectrum’, Journal of Autism and

Developmental Disorders 52, no.8 (August 2022): 3353–3365.

[6]. For example,

Karen Black, ‘Could

Your Teen Refusing to Go to School be a Sign of Mental Health Disability?’ Toronto

Star, 21 February 2023; ‘Breakdown of Routines

During Pandemic Lead to Record School Absenteeism in Japan’, Japan Data

(Nippon.com), 5 December 2022; Jillian Jorgensen, ‘For

Some Chronically Absent Students, the Problem is School Refusal’, Spectrum

News—NY1, 2 March 2023.

[7]. For example,

Matilda Marozzi, ‘School

Refusal Almost Triples Since COVID-19 Lockdowns, Say Parents and Expert’, ABC

News, 12 March 2021.

[8]. Australian

Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA), ‘Student

Attendance’, National Report on Schooling in Australia—Data Portal,

Time Series.

[9]. Centre for

Education Statistics and Evaluation (CESE), Understanding

Attendance – A Review of the Drivers of School Attendance and Best Practice Approaches,

(Sydney: NSW Department of Education, 2022), 11.

[10]. Jodi

Richardson, ‘School

Refusal: What You Can Do to Help’, Dr Jodi Richardson (blog), 24 June 2019;

Evely and Ganim, School

Refusal (Revised).

[11]. Brandy Maynard

et al., ‘Treatment

for School Refusal among Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta‑analysis’, Research on

Social Work Practice 28, no. 1 (2018): 56.

[12]. Maynard et al.,

‘Treatment for School

Refusal among Children and Adolescents’, 57.

[13]. Maynard et al.,

57.

[14]. Sophie Black, ‘"Families

Can Fall Apart over This Stuff”: The Children Refusing to Go to School’, Guardian, 26

September 2022.

[15]. See, for

example, Sophie Black, ‘"No

one Really Knows”: Senate Inquiry into School Refusal Told First Step is to

Track “Invisible” Students’,

Guardian, 25 February 2023, 1; Adam Carey and Madeleine Heffernan, ‘More

Students Refusing to Go to School Post Pandemic’, Age, 2 February 2023; Penny

Allman-Payne, Reference:

Education and Employment References Committee—School Refusal, Senate, Debates,

27 October 2022, 1722.

[16]. Burch, ‘School

Refusal: When a Child Won’t Go to School’.

[17]. Burch; Heyne et al., ‘Differentiation

Between School Attendance Problems’.

[18]. Heyne et al.

[19]. Heyne et al.

[20]. Havik and

Ingul, ‘How

to Understand School Refusal’: 7.

[21]. J. Sergejeff,

T. Pilbacka-Rönkä, and H. Mantila, School

Refusal: A Small Guide to Supporting School Attendance, Tuuve and Monni

Online Projects, n.d.

[22]. See, for

example, ‘School

Can’t, A National Crisis We Can No Longer Ignore’, Living on the

Spectrum (blog), 23 January 2023; ‘School

Phobia/School Refusal’, Encyclopedia of Children’s Health; ‘Emotionally

Based School Avoidance (EBSA)’, Support Services for Education (UK).

[23]. Sewell, ‘School Refusal’; Havik and Ingul, ‘How

to Understand School Refusal’;,South Eastern Sydney Local Health District

(SESLHD), School

Refusal—Every School Day Counts, (Sydney: SESLHD, 2014), 3.

[24]. SESLHD, School

Refusal, 3.

[25]. SESLHD, School

Refusal, 3.

[26]. Totsika et al.

‘Types and Correlates

of School Non-attendance in Students with Autism Spectrum Disorders’.

[27]. Adams, ‘Child and

Parental Mental Health as Correlates of School Non-attendance and School

Refusal in Children on the Autism Spectrum’: 3358.

[28]. Brett Henebery,

‘Improving

Student Attendance Starts with a Sense of Belonging – Expert’, The Educator,

15 November 2022.

[29]. Marozzi, ‘School

Refusal Almost Triples since COVID-19 Lockdowns’.

[30]. See Black, ‘Could

Your Teen Refusing to Go to School be a Sign of Mental Health Disability?’;

‘Breakdown of Routines

During Pandemic Lead to Record School Absenteeism in Japan’; Jorgensen, ‘For

Some Chronically Absent Students, the Problem is School Refusal’.

[31]. Office for

Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills (OFSTED), Securing

Good Attendance and Tackling Persistent Absence, (London: OFSTED,

2022).

[32]. OFSTED, Securing

Good Attendance and Tackling Persistent Absence.

[33]. Allman-Payne, Reference:

Education and Employment References Committee, 1722.

[34]. Senate

Education and Employment Committee, ‘The

National Trend of School Refusal and Related Matters’, Inquiry homepage, Parliament of Australia.

[35]. Australian

Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA), National

Report on Schooling in Australia 2021, (Sydney: ACARA, 2023), 29.

[36]. ACARA, ‘Student

Attendance’, National Report on Schooling in Australia—Data Portal.

[37]. Jim Watterston

and Megan O’Connell, Those

who Disappear, (Melbourne: University of Melbourne, 2019).

[38]. Centre for

Education Statistics and Evaluation (CESE), Understanding

Attendance – A Review of the Drivers of School Attendance and Best Practice Approaches,

(Sydney: NSW Department of Education, June 2022), 11.

[39]. CESE, Understanding

Attendance, 11.

[40]. Australian

Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL), Spotlight—Attendance

Matters, (Sydney: AITSL, 2019), 4.

[41]. ACARA, ‘Student

Attendance’, National Report on Schooling in Australia—Data Portal,

Time Series.

[42]. ACARA, ‘Student

Attendance’, Time Series.

[43]. AITSL, Spotlight—Attendance

Matters, 5.

[44]. ACARA, ‘Student

Attendance’, School year by state/territory.

[45]. AITSL, Spotlight—Attendance

Matters, 6.

[46]. ACARA, ‘Student

Attendance’, School year by state/territory.

[47]. AITSL, Spotlight—Attendance

Matters, 7.

[48]. ACARA, ‘Student

Attendance’, Indigenous Status by State/Territory.

[49]. ACARA, ‘Student

Attendance’, School Sector by State/Territory.

[50]. Richardson, ‘School

Refusal: What You Can Do to Help’; see also ‘School Refusal

(Revised)’, Psych4Schools.

[51]. Maynard et al.,

‘Treatment for School

Refusal among Children and Adolescents’, 56; Joanne Garfi, Overcoming School

Refusal, (Samford Valley, QLD: Australian Academic Press, 2018), 2.

[52]. Christopher

Kearney, ‘School Absenteeism and School Refusal Behavior in Youth: A Contemporary

Review’, Clinical Psychology Review 28, (2008): 451–471; St. Joseph, et

al., School

Refusal: Assessment and Intervention, (Center on Positive Behavioral

Interventions and Supports, 2022), 3–4.

[53]. Statped

(coordinating organisation), Problematic

School Absenteeism—Improving Systems and Tools, (Erasmus+ Strategic

Partnerships, 2021), 15–16.

[54]. Roisin Devenney

and Catriona O’Toole, ‘”What Kind of Education System

Are We Offering”: The Views of Education Professionals on School Refusal’, International

Journal of Educational Psychology 10, no. 1, (February 2021): 29.

[55]. Devenney and

O’Toole, ‘”What Kind

of Education System Are We Offering”’, 29.

[56]. Statped, 16–18.

[57]. Statped, 10.

[58]. Maynard et al.,

57.

[59]. Maynard et al.,

57.

[60]. Maynard et al.,

57; Black, “Families

Can Fall Apart over This Stuff”.

[61]. Maynard et al.,

57.

[62]. Christopher

Kearney, Carolina Gonzálvez, Patricia Gracczyk and Mirae Fornander, ‘Reconciling

Contemporary Approaches to School Attendance and School Absenteeism: Toward

Promotion and Nimble Response, Global Policy Review and Implementation, and

Future Adaptability (Part 1)’, Frontiers in Psychology 10, no. 2222

(October 2019): 2; Mandy Allison and Elliott Attisha, ‘The

Link between School Attendance and Good Health’, Pediatrics 143, no.

2, (February 2019), e20183648.

[63]. Kristen

Hancock, Carrington Shepherd, David Lawrence and Stephen Zubrick, Student Attendance

and Educational Outcomes: Every Day Counts, Report prepared for

Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations, (Perth: Telethon

Institute for Child Health Research and Centre for Child Health Research,

University of Western Australia, 2013), v.

[64]. Hancock et al.,

Student Attendance

and Educational Outcomes: Every Day Counts, vi.

[65]. Hancock et al.,

vi.

[66]. Hancock et al.,

vi.

[67]. Michael

Gottfried, ‘Chronic Absenteeism

in the Classroom Context: Effects on Achievement’, Urban Education 54, no. 1, (December

2015): 3–34.

[68]. Devenney and

O’Toole: 37.

[69]. Devenney and

O’Toole: 38.

[70]. Devenney and

O’Toole: 38.

[71]. Jess Whitley

and Beth Saggers, ‘School

Attendance Problems Are Complex and Our Solutions Need to Be as Well’, Conversation,

1 November 2022.

[72]. Devenney and

O’Toole: 34.

[73]. Devenney and

O’Toole: 35.

[74]. See ‘How

schools are funded’, Australian Government Department of Education website.

[75]. For example,

see Statped, Problematic

School Absenteeism—Improving Systems and Tools; CESE, Understanding

Attendance.

[76]. Black, ”Families

Can Fall Apart Over This Stuff”; Adam Langenberg, ‘Mental

Health Issues Described as “Key Driver of Non‑attendance”, as Students Stay

Away from Schools’,

ABC News, 7 February 2023.

[77]. Tamsin Rose, ‘Early

Interventions ”Missed” as NSW Struggles with Shortage of School Counsellors’, Guardian, 8

October 2022; see also, Lisa Wachsmuth, ‘”We

Must Pick up the Kids We Can Help”’, Sunday Telegraph, 27 November

2022.

[78]. Australian

Psychological Society (APS), The

Framework for Effective Delivery of School Psychology Services: A Practice Guide

for Psychologists and School Leaders, APS Professional Practice (APS,

2016), 30–1.

[79]. Geoff Gallop,

Tricia Kavanagh and Patrick Lee, Valuing

the Teaching Profession—An Independent Inquiry, (Sydney: NSW Teachers

Federation, 2021), 11.

[80]. Whitley and

Saggers, ‘School

Attendance Problems are complex’; Jane Sundius, ‘Reducing

Chronic Absence Requires Problem Solving and Support, Not Blame and Punishment’,

Attendance Works (blog), 4 April 2018.

[81]. Whitley and

Saggers, ‘School

attendance problems Are Complex’; Kristen Hancock, Michael Gottfried and

Stephen Zubrick, ‘Does

the Reason Matter? How Student-reported Reasons for School Absence Contribute

to Differences in Achievement Outcomes among 14–15 Year Olds’, British

Educational Research Journal 44, no. 1 (February 2018): 141–174.

[82]. Hancock et al.,

‘Does

the Reason Matter?’, 142.

[83]. Matthew Bach, ‘Opinion:

School Refusers Need to Receive Tough Love’, Age, 31 January 2023.

[84]. Christine Grové

and Alexandra Marinucci, ‘You

Can’t Fix School Refusal with “Tough Love” but These Steps Might Help’, Conversation,

6 February 2023.

[85]. Sallyanne

Marlow and Neelofar Rehman, ‘The

Relationship between Family Processes and School Absenteeism and Dropout: A

Meta-analysis’, Educational and Developmental Psychologist 38, no.

1, (2021): 3–23.

[86]. Marlow and

Rehman, ‘The

Relationship between Family Processes and School Absenteeism and Dropout: A Meta-analysis’,

12.

[87]. Shannon Clark, COVID-19:

Chronology of State and Territory Announcements on Schools and Early Childhood

Education in 2020, Research paper series, 2021–22 (Canberra:

Parliamentary Library, 2022).

[88]. Education

Ministers Meeting, Communique,

27 February 2023.