Tim Brennan, Science, Technology, Environment and Resources

Key issue

Australia has a well-performing research sector but has consistently been less successful translating research outcomes into commercially successful products and services.

In relation to spending on research and development, Australia is well behind international leaders and middle ranked among developed nations. Many stakeholders, particularly in the university sector, believe that the research funding system needs reform, both in terms of the quantity of funding and how it is invested.

Introduction

Parliament is often required to consider issues involving

complex scientific concepts and where future impacts are uncertain. Similarly,

the Australian Government relies on access to a strong evidence base for the

development of policies to protect health and wellbeing and foster economic

growth. It is therefore imperative that parliamentarians and government have

access to expert advice on a wide range of issues.

The COVID-19 pandemic, and the rapid development of

vaccines, have highlighted

the critical role of science in protecting social wellbeing. Ensuring that

policy frameworks encourage the research and development (R&D) that can

address challenges, such as the pandemic, helps underpin the long-term

resilience of Australian society. Additionally, Australia’s prosperity will

increasingly be linked to its ability to commercialise R&D into new

innovations and industries.

The development of successful new products and

services is the last step in a process of knowledge generation and transfer

that can take decades. The funding of this R&D and commercialisation

process by governments and industry in Australia is well behind international

leaders.

Despite research commercialisation being a focus of

Australian Government policy for decades, Australia continues to perform

relatively poorly in this area. Additionally, there are emerging concerns that

the long-term focus on commercialisation may be coming at the expense of the

basic research that forms the foundations of the innovation ‘pipeline’.

Scientific advice to Parliament

The provision of advice from the science sector to parliamentarians

can occur through a variety of mechanisms, including via direct engagement with

researchers, and through Science

Meets Parliament and the Australian Council of

Learned Academies (ACOLA, which includes the Australian Academy of Science and the Australian Academy of Technology and

Engineering). The Parliamentary Library Research Branch also provides customised

information, analysis and advice on any subject of interest to parliamentarians

and their staff and to support parliamentary committees.

Parliamentary committees due to their

smaller size and more informal procedures (relative to the 2 chambers)

are ‘well suited to the gathering of evidence from expert groups or

individuals’ (p. 641). Committees undertake inquiries on matters of policy

and public interest and seek input from stakeholders to inform their

deliberations. This input regularly includes evidence from the academic

community and other experts provided through written submissions and oral presentations

at public hearings.

Advice and policy support for Government

The new Minister for Industry and Science, Ed

Husic, will be the 11th

minister to hold the science portfolio in the last decade. In the new Government,

science policy will sit within the Department of Industry, Science and

Resources (p. 28). In addition to the department, there are several major

sources of science policy advice to government, as outlined below.

CSIRO

The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research

Organisation is Australia’s public sector applied research

organisation. CSIRO is a statutory authority constituted under the Science and

Industry Research Act 1949 (SIR Act). CSIRO describes its

purpose as ‘solving

the greatest challenges through innovative science and technology’ and its functions

under the SRI Act include undertaking research to support Australian

industry and the Australian community. An example of these functions are the roadmaps

that CSIRO regularly publishes, which investigate opportunities for Australian

industry to take advantage of new and emerging technologies. In 2021–22,

the Australian Government provided $949 million in funding to CSIRO (p. 253).

The Chief Scientist

Australia’s Chief

Scientist provides independent advice on science, technology, and

innovation to the Prime Minister and other ministers. The Chief Scientist’s

role also includes advocating for Australian science internationally and

championing the importance of scientific evidence to the Australian public. The

Chief Scientist holds the position of Executive Officer to the National

Science and Technology Council, which is chaired by the Prime Minister and

is the ‘preeminent forum for providing scientific and technological advice for

government policy and priorities’.

Dr Cathy Foley is Australia’s ninth Chief Scientist.

She commenced in the role in January 2021 (replacing Dr Alan Finkel). At the commencement

of her tenure as Chief Scientist, Dr Foley identified the 4 foundational

issues she hoped to work on: digital capability; science, technology,

engineering and mathematics (STEM) education; diversity in the research

community; and open access to research (p. 6).

Industry Innovation and Science Australia

Innovation and Science Australia (ISA) was established

in 2015 as part of the National

Innovation and Science Agenda (NISA). ISA is an independent statutory board

of entrepreneurs, investors, researchers and educators tasked with

providing advice to Government as well as coordinating innovation policy across

multiple portfolios. ISA has published many reports

on innovation policy.

In 2021, ISA’s name

was changed to Industry Innovation and Science Australia (IISA) to

emphasise the Government’s efforts to increase the links between science and

industry.

Evolving science and innovation policy frameworks

Since the 1980s, Australian innovation policy has

gone through several

distinct phases. Policy settings have ranged from more ‘interventionist’

approaches that attempted to build collaboration within an innovation system

(including between government and industry) and more ‘free market’ approaches

that aimed to use incentives to increase the pace, rather than change the direction,

of innovation (pp. 182–184).

Some major science and innovation programs and

reports within the last decade include:

- The 2015 National

Innovation and Science Agenda (NISA) was a $1.1 billion program of 24 measures

across 4 areas (p. 18). The measures included funding for the Square

Kilometre Array telescope system, the creation of the CSIRO

Innovation Fund, and the Biomedical

Translation Fund.

- ISA’s 2017 report Australia 2030:

prosperity through Innovation, a strategic plan for the innovation

system, made 30 recommendations across education, industry, government,

research and development, and culture and ambition (p. 4). In May 2018,

the Government released its response to the 2030 Plan- which included support

for 17 of the recommendations.

- The Australian Government’s $1.3 billion Modern

Manufacturing Initiative in 2020 marked a move towards assistance targeted

at specific areas of competitive advantage. These areas, known as the National

Manufacturing Priorities, are resource technology and critical minerals

processing, food and beverage, medical products, recycling and clean energy,

defence, and space.

- ISA’s 2021 report Driving

effective Government investment in innovation, science and research

recommended the development of whole-of-government priorities and a 10-year

investment plan, which would include investments balanced over the short,

medium, and long-term.

Should science advice to Parliament be expanded?

There have been suggestions that additional

mechanisms are required to increase the provision of independent science advice

to Parliament and all parliamentarians. For example, a 2021 Senate

Committee recommended a ‘Parliamentary Office of Science’ be established

and modelled on the UK’s Parliamentary

Office of Science and Technology (POST). The Australian Academy of Science

is continuing to stimulate

this debate, and highlighted the Parliamentary Budget Office as a successful

example of another body providing advice to Parliament.

The Australian Labor Party’s (ALP) 2021 National

Platform states that the ALP will establish a Parliamentary Office of

Science to ‘provide independent, impartial scientific advice, evidence and data

to the Parliament, and all Members and Senators’ (p. 68). The Australian

Greens are also committed

to the establishment of an independent POST.

Open access publications

Australian researchers are largely funded by the taxpayer. Despite this, a significant proportion of Australian research is published in paywalled academic journals that are not accessible to the public. For many years there have been attempts to increase the amount of research provided in ‘open access’ formats that can be accessed freely. The Australian Research Council and NHMRC both have open access policies requiring outputs from publicly funded research to be openly accessible within 12 months of publication. However, partly due to caveats related to legal and contractual obligations, the majority of Australian publications remain published in formats that are not open access.

The Chief Scientist has stated that supporting the development of a national open-access policy for academic journals would be one of her priorities and has developed an Australian Model for Open Access. Under this model, a single national body would negotiate a fee with publishers. This fee would provide research papers free of charge to all Australians and ensure papers by Australian researchers are published internationally as open access.

Spending on science, research, and innovation

The Global

innovation index (GII) is an annual report providing statistical

benchmarking of national innovation systems. The 2021

edition of the GII ranked Australia 25th of the 132 countries assessed (p. 47)

and 24th of the 51 high-income

countries.

As in previous years, Australia ranks well (15th)

on innovation inputs including education and research, but less well (33rd) on

innovation outputs, suggesting a weakness in translating research into

commercial outcomes. Further analysis of the performance of Australia’s

innovation system relative to other countries can be found in the Australian

Innovation System Monitor.

In 2019–20, Australian gross

expenditure on research and development (GERD), which includes research spending by business,

government, higher education and the non-profit sector, was $35.6 billion. This

amounts to 1.79% of GDP, placing

Australia 20th among 132 countries for this metric (p. 47). GERD as a

proportion of GDP has been falling

since 2008 (p. 40). In 2019, business expenditure on research and

development (BERD) in Australia was 0.92% of GDP, which is approximately

half the OECD average (1.81%; p. 33). The ALP

has committed to increasing investment in research and innovation to levels

closer to 3% of GDP (p. 7)

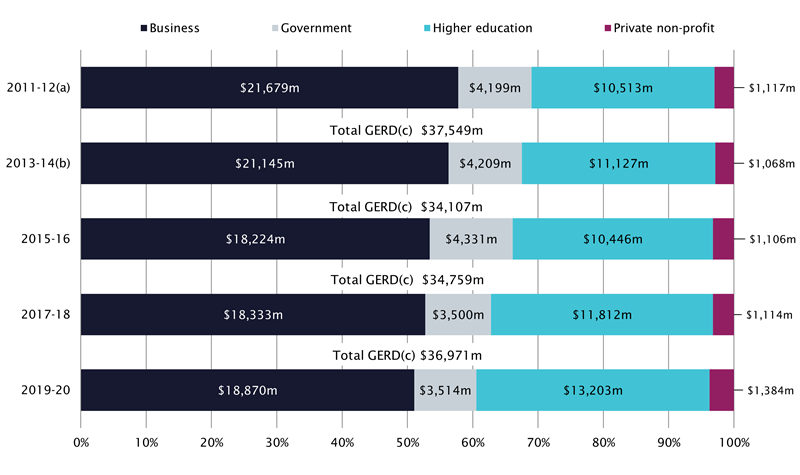

Figure 1 shows spending on R&D since 2011–12

converted to 2021 prices. Although total spending remained relatively steady

(in 2021 prices), business and government spending dropped, and higher

education spending rose over this period.

Figure 1 Gross expenditure on

research and development (GERD) by sector (in 2021 prices)

(a) Higher education estimates

modelled in 2011–12.

(b) From 2013–14 Government, Private

non-profit and Higher education estimates have been modelled.

(c) Where figures have been rounded,

discrepancies may occur between the sum of the component items and totals.

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics

(ABS), Research

and Experimental Development, Businesses, Australia, 2019–20 Financial Year,

(Canberra: ABS, 2021). All figures have been converted to June 2021 prices

using Parliamentary Library calculations.

The declining level of

business expenditure on research is largely due to changes in Australia’s industry

mix, including a decline in manufacturing and a transition in the mining sector

from exploration and development to operations (p. 37).

Aggregate figures for Australian Government

spending are also provided in the annual Science,

Research and Innovation Budget Tables. In 2021–22, the estimated total government

spending on science, research and innovation was $11.8 billion (note that this

includes support for business and higher education, which in Figure 1 is

allocated to each of those sectors).

Australian Government investment in 2021–22 comprised:

- Australian Government research activities: $2.3 billion, including

CSIRO, Defence Science and Technology Group, and other government R&D

- business enterprise sector: $2.9 billion, almost all of which is

spent on the R&D Tax Incentive, which provides a tax offset for businesses

to undertake R&D activities

- higher education sector: $3.7 billion, including the research block

grants, Australian Research Council grants, and NHMRC grants to universities

- multisector: $2.8 billion, including NHMRC’s non-university

spending, Cooperative Research Centres, Rural R&D Corporations, other

health R&D, and energy and environment R&D.

University research funding

Australian universities receive funding to

undertake research from a variety of sources. The largest source of funding

(56%) is from general university funds. Other key sources of funding include:

- research

block grants, which provide funding for research and research training ($2

billion in funding in 2022)

- various competitive grants programs including: the Australian

Research Council administered National

Competitive Grants Program (which includes the Discovery Program for

foundational research and the Linkage Program for research undertaken in

partnership with industry); NHMRC

grants; and Medical

Research Future Fund grants

- student fees and government support for research infrastructure.

A more detailed discussion on university research

funding can be found in the Parliamentary Library’s quick

guide on the subject.

Workforce issues

In 2020, women made up 13% of employees in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) qualified occupations. The Australian Government has an Advancing Women in STEM strategy and made investments in related programs in the 2021–22 Budget (p. 50). The Chief Scientist has also made increasing the diversity of the STEM workforce a priority and noted there are barriers for women not just during education but throughout other career stages.

It is estimated that as many as 70% of staff at Australian universities are employed as casuals or on insecure contracts. In many cases, casual academics were the first to lose their jobs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, there have been reports that casual and contract staff being required to do unpaid work, or otherwise underpaid, is endemic within Australian universities, with at least 21 Australian universities implicated in the practices. There are suggestions that these working conditions are contributing to a ‘brain drain’ of researchers out of the Australian university sector.

Research commercialisation agenda

The Australian university sector is generally

highly ranked in international comparisons of research performance. In 2022, there

are 7 Australian universities in the Top 100 of the QS World

University Rankings and 6 in the Top 100 of the Times

Higher Education rankings.

Australian researchers also perform well in

measurements of academic publications, producing

4.1% of academic publications globally in 2020, more than 10 times

Australia’s share of the global population (0.3%). Australian authors perform

well when comparing citations of research publications. Australian researchers

also perform above the OECD average in terms of scientific publications

generated per dollar invested in research.

Despite these successes, Australian research does

not appear to be as effective at being translated into successful commercial

products. This is a long-standing

problem that has been the focus of the efforts of successive governments to

expand the innovative capacity of the Australian economy. It has long been

thought that insufficient knowledge transfer, in part due to a lack

of collaboration between industry and Australian public sector researchers,

contributes to the low levels of commercialisation.

Australia

ranks last in the OECD (by a significant margin) in relation to the

percentage of businesses that develop innovations in collaboration with public

sector research organisations. As shown in the Australian

Innovation System Monitor, this

result ‘reflects unfavourably on the ability of Australian

businesses and research institutions to maximise the return on public

investment in science and research’.

The 2016 Review

of the R&D Tax Incentive recommended a collaboration premium be added

to the R&D

Tax Incentive to provide a financial incentive to businesses to collaborate

with public sector research organisations (p. 3). This recommendation was reiterated

in ISA’s Australia

2030 report (p. 104). To date, the Australian Government has not

implemented this recommendation.

In 2021, the Morrison Government announced the University Research

Commercialisation Action Plan (Commercialisation Action Plan), a $2.2

billion investment to drive commercialisation and increase collaboration

between industry and universities. Key components of the plan include:

- $1.6 billion for Australia’s

Economic Accelerator, which will provide grant funding to universities with

projects at proof-of-concept or proof-of-scale projects that have high

commercialisation potential and are aligned to one of the National

Manufacturing Priorities

- $296 million for the National

Industry PhD Program to support 1,800 students to undertake

industry-focused PhDs

- $243 million for the Trailblazer

Universities Program, a competitive grant program that will select universities

to partner with industry to work on research aligned with the National

Manufacturing Priorities.

The announcement of Australia’s Economic

Accelerator was largely supported

by stakeholders

within the science and research field. The Morrison Government introduced 2 Bills

to legislate Australia’s

Economic Accelerator and the Trailblazer

Universities Program, which lapsed at the dissolution of the 46th Parliament.

Prior to the election, the ALP

indicated it would support legislating Australia’s Economic Accelerator and

stated in its National

Reconstruction Fund policy that it would invest in supporting Australian

companies to commercialise new renewable energy and low emissions technologies.

The ALP earlier announced it would introduce a Startup

Year program which would offer loans to 2,000 final-year students and

recent graduates to support their participation in commercialisation

accelerator programs.

Labor has also committed to creating an Advanced

Strategic Research Agency (ASRA) in the Defence portfolio, emphasising that

‘ASRA would be modelled after the United States Government’s ground-breaking

Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA)’. For further information,

see the article on ‘The Australian Government public sector’ elsewhere in this

Briefing book, and a Parliamentary Library FlagPost about the

‘DARPA model’.

Commercialisation concerns

There are concerns among some university

stakeholders that the focus on research translation could come at the expense

of support for foundational or basic research that is not suitable for

commercialisation.

The Vice-Chancellor of the Australian National University, Professor Brian Schmidt, highlighted that applied research builds on

existing basic research and argued

that the new Government should ensure that the right balance is struck

between basic and applied research.

The President of the Australian Academy of Science,

Professor John Shine, highlighted

the role of fundamental science in gradually building the understanding of

RNA technologies necessary for the rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines.

Professor Shine stated that government funding for research should act as

‘patient capital’ and quick or easy returns should not be expected.

Researchers in the humanities and social sciences have

also noted that the Commercialisation Action Plan’s focus on the National

Manufacturing Priorities means that it will be almost

impossible for researchers in these fields to attract funding under the

plan.

Calls for reforms to research funding

Many university stakeholders are calling for

reforms to how research is funded in Australia. These range from a focus on specific

issues, such as removing the ability of ministers

to intervene in the approval of Australian Research Council grants, to calls

for broad systemic reform.

The Australian

Academy of Science stated that Australia’s approach to funding science is

‘not fit for purpose’ and recommended a whole-of-government review to ‘identify

the optimal operation, funding arrangements and architecture of the Australian

science and research system’.

Similarly, the Vice-Chancellor of the University of

Melbourne, Professor Duncan Maskell, stated there is a need to ‘tear

up our research funding model and … start from scratch’. Professor Maskell suggested

that the Government should fund a higher proportion of research so that it does

not need to be subsidised by international student fees. Professor Schmidt

stated that the Albanese Government had a ‘clean slate’ to fix ‘long-standing

problems with the research ecosystem in Australia’.

Further reading

Industry Innovation and Science Australia (IISA), Driving Effective Government Investment in Innovation, Science and Research, (Canberra: IISA, January 2021).

Tim Brennan, Hazel Ferguson and Ian Zhou, ‘Science and research’, Budget Review 2022–23, Research paper, 2021-22, (Canberra: Parliamentary Library, April 2022), 80–84.

Hazel Ferguson, University Research Funding: a Quick Guide, Research paper series, 2021–22, (Canberra: Parliamentary Library, February 2022).

Tim Brennan and Hazel Ferguson, ‘Independence of the Australian Research Council’, FlagPost (blog), Parliamentary Library, 3 June 2022.

Back to Parliamentary Library Briefing Book

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.