Bills Digest No. 12, 2017-18

PDF version [787KB]

Paula Pyburne

Law and Bills Digest Section

10

August 2017

Contents

Purpose of the Bill

Structure of the Bill

Background

Setting food safety standards

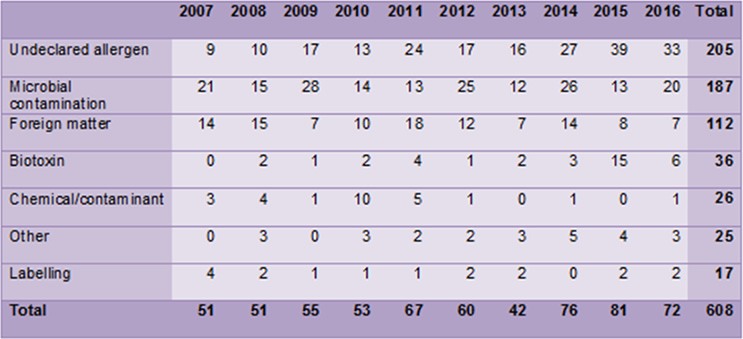

Table 1: number of recalls

coordinated by FSANZ, by year and classification, between 1 January 2007 and 31

December 2016

Role of the ACCC

Level of Australian imports

Table 2: Australia’s food imports

unprocessed and processed (A$ million)

Importation of contaminated berries

Costs of the contamination

Imported Food Control Ac

Application

Imported Food Inspection Scheme

Referral for inspection

Table 3: Examples of tests applied

Reviews

2015—Australian National Audit Office

2016—Food importer research

Regulation impact statement

Committee consideration

Selection of Bills Committee

Senate Standing Committee for the

Scrutiny of Bills

Policy position of non-government

parties/independents

Position of major interest groups

Financial implications

Statement of Compatibility with Human

Rights

Parliamentary Joint Committee on

Human Rights

Key issues and provisions

Food safety management certificates

Commencement

Background

Key provisions

Key issue

Scrutiny of Bills Committee

Making of orders of determinations

Commencement

Key provisions

Holding orders

Commencement

Key provisions

Scrutiny of Bills Committee

Classification of food

Commencement

Key provisions

Recognition of foreign country’s food

safety system

Commencement

Key provisions

Enforcement

Commencement

Key provisions

Updated offences

New civil penalty provisions

Enforcement under the Regulatory

Powers Act

Monitoring powers

Issuing a monitoring warrant

Investigation powers

Issuing an investigation warrant

Scrutiny of Bills Committee

Enforceable civil penalty provisions

Other enforcement options

Infringement notices

Enforceable undertakings

New Part 4—other matters

Power to require information or

documents

Record keeping

Commencement

Key provisions

Use and disclosure of information

Commencement

Key provisions

Use of information

Disclosure of information

Scrutiny of Bills Committee

Other amendments

Commencement

Key provisions

Concluding comments

Date introduced: 1

June 2017

House: House of

Representatives

Portfolio: Agriculture

and Water Resources

Commencement: various

dates as set out in the body of this Bills Digest

Links: The links to the Bill,

its Explanatory Memorandum and second reading speech can be found on the

Bill’s home page, or through the Australian

Parliament website.

When Bills have been passed and have received Royal Assent,

they become Acts, which can be found at the Federal Register of Legislation

website.

All hyperlinks in this Bills Digest are correct as

at August 2017.

Purpose of

the Bill

The purpose of the Imported Food Control Amendment Bill

2017 (the Bill) is to amend the Imported Food

Control Act 1992 in order to deliver the

following objectives:

- increase importers’ accountability for food safety

- increase the number of importers who are sourcing safe food

- improve monitoring and management of new and emerging food safety risks

and

- improve incident responses.[1]

Structure

of the Bill

The Bill comprises one Schedule of nine Parts.

Part 1: introduces the concept of food safety

management certificates.

Part 2: allows the Secretary to make a holding

order in respect of food posing a serious risk to human health.

Part 3: empowers the Minister to make orders

identifying particular foods which pose new and emerging risks.

Part 4: allows for the recognition of a foreign

country’s food safety regulatory system where it is equivalent to Australia's

food safety system.

Part 5: sets out increased enforcement measures.

Part 6: updates recordkeeping measures.

Part 7: introduces a power to make an order or a

determination under the Imported Food Control Act.

Part 8: applies to the use and disclosure of

information.

Part 9: aligns the definition of food

with other Commonwealth legislation.

Background

Setting food safety standards

The Commonwealth of Australia and all the Australian

states and territories are signatories to an inter‑governmental agreement,

the Food Regulation Agreement.[2]

In addition, to reduce industry compliance costs and to help remove regulatory

barriers to trade between the two countries, Australia and New Zealand are

party to a bilateral agreement, the Agreement between the Government of

Australia and the Government of New Zealand concerning a Joint Food Standards

System.[3]

The system operates through the Food Standards

Australia New Zealand Act 1991 (FSANZ Act) which establishes

Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ).

The role of FSANZ is, amongst other things, to develop food

regulatory measures—that is, food standards or codes of practice. Relevant to

this Bills Digest, FSANZ has developed the Food Standards Code,[4]

Chapter 3 of which contains the Food Safety Standards.[5]

Consistent with clauses 19–27 of the Food Regulation

Agreement, it is for the states and territories to enact statutes which incorporate

the food standards contained in the Code.[6]

Those statutes adopt Model Food Provisions. This means that every jurisdiction

in Australia largely has the same provisions for key components of food

legislation such as:

- definitions

for food, unsafe food and unsuitable food

- offences

relating to food and

- emergency

powers.

Where food is subject to a recall on a national level,

that food recall is co-ordinated by FSANZ.[7]

Food recall powers are exercised by state and territory authorities under state

and territory laws which operate post-border.[8]

The table below shows the number of

recalls by year and recall classification over the last ten years.

Table 1: number

of recalls coordinated by FSANZ, by year and classification, between 1 January

2007 and 31 December 2016

Source: Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ), ‘Food recall statistics’,

FSANZ website.

Role of the ACCC

In addition to the requirements of the Food Regulation

Agreement—and working in tandem with those requirements—subclause 131(1) of the

Australian Consumer Law[9]

provides that, where a person who supplies consumer goods[10]

(including foods) becomes aware of the death or serious injury or illness of

any person—and considers that the death or serious injury or illness was

caused, or may have been caused, by the use or foreseeable misuse of the

consumer goods—then the supplier must, within two days of becoming so aware,

give the Commonwealth Minister a written notice to that effect. A supplier of

consumer goods must similarly notify the Commonwealth Minister where he, or

she, becomes aware that a person, other than the supplier, considers that the

death or serious injury or illness was caused, or may have been caused, by the

use or foreseeable misuse of the consumer goods.

Level of Australian imports

The table below sets out the monetary value of unprocessed

and processed food imports to Australia.

Table 2: Australia’s

food imports unprocessed and processed (A$ million)

|

|

2013–14

|

2014–15

|

2015–16

|

% growth 2014–15 to 2015–16

|

% growth

5 year trend

|

|

Unprocessed

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Live animals, chiefly for food

|

112

|

102

|

113

|

11.8

|

-1.5

|

|

Seafood, fresh, chilled, dried, smoked, salted

|

336

|

338

|

364

|

7.5

|

7.8

|

|

Vegetables, fruit and nuts, fresh, chilled, or provisionally

preserved

|

842

|

973

|

1,028

|

5.7

|

10.6

|

|

Cereal grains

|

26

|

27

|

19

|

-31.3

|

33.9

|

|

Unprocessed food (not elsewhere specified)

|

605

|

726

|

835

|

15.0

|

6.9

|

|

Processed

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Meat and meat preparations

|

646

|

790

|

790

|

-0.1

|

8.0

|

|

Seafood, frozen or processed

|

1,447

|

1,431

|

1,436

|

0.4

|

8.1

|

|

Dairy products

|

780

|

803

|

910

|

13.3

|

9.4

|

|

Vegetables, fruit and nut preparations

|

1,285

|

1,412

|

1,537

|

8.8

|

8.4

|

|

Cereal preparations

|

228

|

256

|

267

|

4.5

|

7.1

|

|

Animal and vegetable oils, fats and waxes

|

620

|

660

|

775

|

17.6

|

5.1

|

|

Sugars, honey, cocoa and confectionery

|

1,164

|

1,314

|

1,464

|

11.4

|

9.9

|

|

Preparations of food, beverages and tobacco (not elsewhere

specified)

|

6,823

|

7,496

|

8,631

|

15.1

|

13.3

|

Source: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Composition

of Trade Australia 2015–16, p. 54.

Importation

of contaminated berries

In February 2015, it was reported that evidence had

emerged of members of the public developing hepatitis A arising from

consumption of imported berries.[11]

Victoria's Department of Health and Human Services confirmed the contamination

had been traced back to China.[12]

Subsequently, a nationwide voluntary recall of certain frozen mixed berries was

undertaken.[13]

It was not until April 2015 that the relevant brand of

frozen mixed berries was reintroduced into the marketplace. According to

Minister for Agriculture, Barnaby Joyce:

The berries used to generate new product will be sourced from

new farms and factories and subject to stricter microbiological testing than

ever before.

This testing includes microbiological testing for Hepatitis A

virus, E.coli and coliforms.

... products from the Chinese factories and farms associated

with the recall are all still being held at the border, in line with directions

given ... by the Department of Agriculture.[14]

Costs of

the contamination

Thirty-three people were confirmed as having contracted

hepatitis A during the 2015 outbreak, the cost of which was:

... an estimated $710 000. After the implicated product was

recalled, the profits of the company that had imported the berries went from

$16.7 million to $2.1 million per year. There are also much broader

implications, with consumer confidence in the safety of frozen berries

plummeting, resulting in a temporary reduction in sales for all brands of

imported berry products. Trade was also affected with some importers in

Australia choosing to no longer source frozen berries from the country of

origin of the implicated product.[15]

Imported Food

Control Act

Application

Whilst the February 2015 hepatitis A outbreak showed Australia’s

food recall system in action, it also called into question Australia's food

inspection regime which is set out in the Imported Food Control Act. It

was generally considered that the contaminated products should have been

detected at the border.[16]

The Imported Food Control Act is intended to provide

for the compliance of food imported into Australia with Australian food

standards and with public health and safety requirements.[17]

It applies to all food imported into Australia with the exception of:

- food

that is imported from New Zealand and is of a kind that is specified by the Regulations

to be food to which the Act does not apply

- prohibited

food

- food

that is imported for private consumption

- food

that is ship’s stores or aircraft’s stores, within the meaning of section 130C

of the Customs

Act 1901 or

- food

that is imported as a trade sample.[18]

The Imported Food Control Act provides that a

person must not import into Australia food that the person knows does

not meet applicable standards (being the standards set by FSANZ as above) or

poses a risk to human health. This is a criminal offence which gives rise to a maximum

penalty of 10 years imprisonment.[19]

Food poses a risk to human health if:

- it

contains: pathogenic micro-organisms or their toxins; micro-organisms

indicating poor handling; non-approved chemicals or chemical residues; approved

chemicals, or chemical residues, at greater levels than permitted; non-approved

additives; approved additives at greater levels than permitted; or any other

contaminant or constituent that may be dangerous to human health or

- it

has been manufactured or transported under conditions which render it dangerous

or unfit for human consumption.[20]

Imported Food

Inspection Scheme

Section 16 of the Imported Food Control Act

provides for Regulations to be made which set out the particulars of the Imported

Food Inspection Scheme (IFIS) which is applicable to all the foods to which the

Act applies.

The IFIS is contained in the Imported Food Control

Regulations 1993. The essential features of the IFIS are:

- there

are three classifications of food

- the

Minister may (on the advice of FSANZ) make orders classifying food as risk

food[21]

- compliance

agreement food is food to which a compliance agreement applies[22]

- surveillance

food[23]

- all

food to which the Imported Food Control Act applies may be

inspected under the IFIS[24]

- all risk foods must be referred by the Australian Customs Service for

inspection and five per cent of consignments of surveillance foods

must be referred by the Australian Customs Service for inspection under the

Scheme[25]

- the

rates of inspection of risk food are either:

-

tightened —under

which each consignment from a particular source is inspected

- normal—under

which 25 per cent of consignments from a particular source are selected

randomly for inspection or

- reduced—under

which five per cent of consignments from a particular source are selected

randomly for inspection[26]

- the

rate of inspection of food that is of a particular kind and classified as risk

food that is imported from a particular source may be raised or lowered[27]

- all surveillance food that is referred for inspection under the IFIS

must be inspected.[28]

If a surveillance food fails inspection, the rate of inspection for future

consignments of that food from that producer is increased to 100 per cent and

stays at this rate until a history of compliance is established.[29]

Referral

for inspection

The referral of food for IFIS inspection is based on 1,500

risk profiles within the Customs Integrated Cargo System. These profiles, which

are created and managed by the Department of Agriculture and Water Resources

(Agriculture), refer food to the IFIS when the consignment information declared

by importers matches certain criteria such as the tariff code, importer,

supplier and country of origin codes.[30]

When there is a match against the profile, the information about the imported

food consignment is electronically transferred to Agriculture’s Import

Management System.

Agriculture then uses this information to undertake the

inspection process. The food safety inspections are undertaken by departmental

staff at ports and warehouses across Australia. The Australian National Audit

Office (ANAO), in its audit report on the administration of the IFIS, explains:

These inspections consist of a visual examination to

determine if the food appears safe and suitable ... In addition, private

laboratories are engaged by Agriculture as “appointed analysts” under the Act

to conduct analytical testing for microbial, chemical and other contamination.[31]

The table below provides examples of the tests applied to

risk food.

Table 3: Examples

of tests applied

|

|

Hazard

|

Tests applied

|

|

Risk food

|

|

|

|

Cheese—soft, semi-soft and fresh

|

Micro-organisms

|

E. coli, listeria monocytogenes, salmonella

|

|

Peanuts and peanut products, pistachios and pistachio

products

|

Aflatoxin

|

Aflatoxin

|

|

Beef and beef products

|

Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE)

|

National competent authority certificate from a country

permitted to trade and includes mandatory declaration

|

|

Seafood—bivalve molluscs such as clams, cockles, mussels,

oysters, pipis and scallops

|

Biotoxins and micro-organisms

|

Paralytic shellfish poisons, domoic acid, E. coli, listeria

monocytogenes

|

|

Surveillance food

|

|

|

|

Milk and cream concentrated powders, including powdered

infant formula

|

Micro-organisms

|

Salmonella

|

|

Fish

|

Chemical

|

Malachite green, nitrofurans (including furaltadone,

nitrofurantoine) and fluoroquinolones (including ciprofloxacin and enrofloxacin)

|

|

Fish

|

Contaminant

|

Histamine

|

|

Fruit—fresh, chilled or frozen, or dried

|

Chemical and micro-organisms

|

Pesticides (including acephate benalaxyl, chlorfenvinphos

and DDT) and E. coli

|

Source: ANAO, Administration

of the Imported Food Inspection Scheme, op. cit., pp. 31–32.

Reviews

Not only did the outbreak in 2015 of hepatitis A linked to

the importation of frozen berries call into question Australia's inspection

scheme at the border it also highlighted some regulatory gaps. That being the

case, the Government took action to identify those gaps and develop strategies

for improvement.

2015—Australian

National Audit Office

The first of these was an audit conducted by the ANAO ‘to

assess the effectiveness of the Department of Agriculture’s administration of

the Imported Food Inspection Scheme’.[32]

The ANAO noted that ‘in the six months to June 2014,

44,648 tests of imported food were undertaken as part of the inspection regime’.[33]

The reported compliance rate was 98.5 percent with most (79 per cent) instances

of non-compliance being due to breaches of labelling requirements.

The ANAO concluded that, ‘in the context of the

legislative framework established for the regulation of imported food, Agriculture's

administration of its responsibilities under the [IFIS] has been generally

effective’.[34]

The ANAO report made only three recommendations which it considered

would improve aspects of Agriculture’s administration of the IFIS. The

Department agreed with each of those recommendations.[35]

2016—Food

importer research

The second review took the form of food importer research

undertaken by Colmar Brunton at the request of the Department of Agriculture

and Water Resources. The rationale of the food importer research was to allow

the Department to establish a database of food importer information to include

demographics, size/turnover, food types, source countries, use of food safety

systems or other assistance for compliance, costs of compliance and state or territory

food business registration/licence details.[36]

It was intended that the information would assist the

Department in the development of further reforms to the management of imported

food. Unfortunately, participation was not compulsory and responses to the

requests for information were less than anticipated.

Regulation

impact statement

The Government circulated a consultation regulation impact

statement on 22 August 2016 for public consultation with comments being

accepted until 30 September 2016.[37]

The consultation related to three proposed options for action, being:

- Option

1—non-legislative improvements

- Option

2—option 1 plus further non-legislative improvements

- Option

3—options 1 and 2 plus changes to primary and consequential subordinate

legislation.

During the consultation period:

- nine submissions were received –

seven from industry associations or businesses, one from government and one

from a registered health promotion charity (promoting food safety)

- no comments were received from

trading partners in response to the Consultation RIS, however, a meeting was

held with members of the Delegation of the European Union at their request in

Canberra and comments [were] expected on the formal WTO notification before it

closes on 23 October

-

three meetings were held with

industry associations and industry representatives.[38]

Whilst the final form of the regulation impact statement

summarises the views of stakeholders, the submissions do not appear to have

been published on the Department's website.

In March 2017, the Minister for Agriculture, Barnaby Joyce,

announced that comprehensive changes would be introduced to give Australian

consumers greater assurance at the supermarket that imported food is safe,

without burdening local importers with unnecessary red tape.

The Coalition Government is committed to keeping Australia’s

borders strong and has set about amending the imported food laws, the changes

include giving the government greater scope to hold food at the border if there

are reasonable grounds to suspect food poses a serious risk to human health.

They address limitations with the current regulatory

framework for the management of imported food safety risks, which were

uncovered following the frozen berries linked to the hepatitis A outbreak in

February 2015.[39]

The Bill contains amendments which put into effect the Government's

preferred option, being Option 3.

Committee

consideration

Selection

of Bills Committee

At its meeting of 22 June 2017, Selection of Bills

Committee deferred consideration of the Bill to its next meeting.[40]

Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

The Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills reported

on the Bill in its Scrutiny Digest of 14 June 2017.[41]

The Committee’s comments are canvassed under the heading ‘Key issues and

provisions’ below.

Policy

position of non-government parties/independents

There has been no public comment in relation to the

provisions of the Bill at the time of writing this Bills Digest.

However, the issue of the use of imported ingredients

which are blended with Australian ingredients was raised in the context of a

separate debate about country of origin food labelling.[42]

Position of

major interest groups

As stated above, the Department of Agriculture and Water

Resources circulated the regulation impact statement for public comment.

However, individual stakeholder submissions do not appear to have been

published.[43]

Financial

implications

According to the Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill, it

will have no financial impact on the Australian Government.[44]

However, it should be noted that the regulation impact statement

states that the ‘estimated annual net cost to businesses to implement [the

government’s preferred option] ... is $216,000 per year across approximately

16,000 businesses importing food averaged over ten years’.[45]

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed

the Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or

declared in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The

Government considers that the Bill is compatible.[46]

Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Human Rights

The Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights reported

on 8 August 2017 that the Bill did not raise human rights concerns.[47]

Key issues

and provisions

Food safety

management certificates

Commencement

The provisions in Part 1 of the Bill commence on the earlier

of a single day to be fixed by Proclamation or 12 months after Royal

Assent.

Background

The regulation impact statement describes the problem to be

addressed as follows:

Australia is also increasingly importing raw and minimally

processed foods as exporting countries are able to address biosecurity risks.

For example, the department [of Agriculture] is currently reviewing the

importation of beef and beef products from certain countries. The primary

processing of raw beef is strictly controlled by many countries, including

Australia, to minimise contamination of the meat during the slaughtering

process with foodborne pathogens, particularly pathogenic strains of Escherichia

coli, which can cause serious illness and death. If Australia is to receive

more imported raw and minimally processed foods, it is important that importers

are obliged to provide assurance that these foods have been produced and

processed to control likely hazards.[48]

Key

provisions

Part 1 of the Bill introduces the concept of food

safety management certificates. Item 4 inserts proposed

section 18A into the Imported Food Control Act to empower the

Secretary to determine, in writing, that, for food of a specified kind, a

specified certificate issued by a specified person or specified body is a

recognised food safety management certificate. In addition, the

Bill requires the Secretary to make written guidelines to which he, or she,

must have regard before making that determination.[49]

The Bill provides that a person must not forge, or utter, knowing it to be

forged, such a certificate. The maximum penalty is imprisonment for 10 years.[50]

Item 1 of the Bill inserts the definition of recognised

food safety management certificate into subsection 3(1) of the Imported

Food Control Act being either a recognised foreign government certificate

or a certificate covered by a determination under subsection 18A(1).

According to the Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill this

amendment:

... seeks to place increased accountability upon importers to

ensure the food they bring into Australia is safe for consumption. [It] makes

amendments to require documentary evidence from importers to demonstrate that

effective internationally recognised food safety controls are in place

throughout the supply chain for particular types of food where at-border testing

alone is insufficient to provide assurance of food safety. The importers will

be required to demonstrate supply chain assurance through a recognised food

safety management certificate.[51]

Key issue

Importantly, the Bill provides that neither the determination,

nor the guidelines, are legislative instruments.[52]

This means that they will not be published on the Federal Register of Legislation,

will not be tabled in the Parliament, and will not be subject to disallowance.[53]

The Bill addresses the issue of publication by requiring the Secretary to

publish both the determination and any relevant guidelines on the Department's

website.[54]

The justification given by the Department for proposed subsection

18A(4) is that neither of these instruments would fall within the

substantive definition of legislative instruments under the Legislation Act

2003. The Department states that this is because the determination and

guidelines merely identify the particular cases or particular circumstances in

which the law, as set out by the Imported Food Control Act and the Regulations

is, or is not, to apply. They do not, of themselves, determine or alter the

content of the law itself.[55]

Scrutiny of

Bills Committee

Although the Scrutiny of Bills Committee accepted that a

determination that a specified certificate is a recognised food safety

management certificate is one of an administrative rather than a legislative

character, it questioned ‘why guidelines ... should not be considered to be

decisions of a legislative character and therefore subject to parliamentary

oversight and accountability’.[56]

That being the case, the Scrutiny of Bills Committee has

requested that the Minister provide advice as to why the guidelines are not to

be included in a disallowable legislative instrument.[57]

Making of

orders of determinations

Commencement

The provisions relating to the making of orders or

determinations are in Part 7 of the Bill. They commence on the day after Royal

Assent.

Key

provisions

The Bill contains a number of amendments which empower the

Minister or Secretary to make certain orders and determinations in relation to

imported food. Item 40 of the Bill inserts proposed section 35B into

the Imported Food Control Act to make it clear that an order or

determination under either the Imported Food Control Act or the Imported

Food Control Regulations may refer to a kind of food by reference to any one or

more of the following:

- the

country or the place of origin of the food

- the

manner in which the food has been produced, processed, manufactured, stored,

packed, packaged, labelled or transported

- the

producer, processor, manufacturer, storer, packer, packager, supplier,

transporter or importer of the food

- the

period within which the food is imported into Australia

- the

physical properties and/or constituents of the food

- the

brand name of the food.

The Explanatory Memorandum states:

... by enabling an order made under the Act to identify food by

a range of characteristics, the order will be more specific and, therefore,

enable targeted at-border intervention consistent with the risks posed by the

particular food.[58]

Holding

orders

Commencement

The provisions in Part 2 of the Bill commence on the day after

Royal Assent.

Key

provisions

Currently, section 15 of the Imported Food Control Act

broadly operates so that if on inspection or analysis, food (or a part of the

food) is found to be failing food[59]

or the Secretary is satisfied that there are reasonable grounds for believing

that food of a particular kind would, on inspection, be identified as failing

food, then the Secretary may, by writing, make a holding order. The effect of

the holding order is that food of that kind that is imported into Australia

after the making of the order must be held in an approved place until an

inspection, or inspection and analysis, required under the IFIS, has been

completed.

The Bill makes significant changes to section 15 by

allowing holding orders to be made in respect of failing food and food posing a

serious risk to human health. The rationale for the amendment is that it will

ensure that ‘the Australian Government has the power to control the spread of

foodborne illness and communicable diseases (such as hepatitis or

listeriosis)’.[60]

Item 7 of the Bill repeals and replaces paragraph

15(1)(c) so that the holding order for failing food must state that the food is

to be held in a place to be approved by an authorised officer in writing, until

an inspection, or inspection and analysis, required under the IFIS has been

completed. The holding order applies to food of the kind specified that is

imported into Australia after the making of the order—until the order is

formally revoked.

Item 10 of the Bill inserts proposed subsections

15(3)-(9) into the Imported Food Control Act so that where the

Secretary is satisfied that there are reasonable grounds for believing that

food of a particular kind may pose a risk to human health and that the risk is

serious he, or she, may, by writing, make a holding order which must state:

- food

of that kind that is imported into Australia after the making of the order must

be held in a place to be approved by an authorised officer in writing until the

order ends

- the

order ends at the earlier of either the end of the period of 28 days

beginning on the day the order is made or, if that period is extended, the end

of the extended period or the time when the order is revoked[61]

and

- the

circumstances in which the order will be revoked.[62]

The Secretary may, in writing, extend the 28‑day

period of a holding order in respect of food posing a serious risk to human

health for a further period of up to 28 days. The Secretary may make more than

one such extension.[63]

However, before making an extension, the Secretary must review the appropriateness

of the order.[64]

According to the Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill:

The intent of a holding order made under new subsection 15(3)

of the Act is to merely preserve the status quo, and temporarily prevent a

particular food from further distribution until sufficient scientific evidence

can be gathered and the safety of that food can be determined. If the food is

determined not to be a risk to human health, the order will be revoked; if the

food is determined to be a risk to human health, a decision will then be made

to deal with the food.[65]

Accordingly, it is possible that at the end of the period

of a holding order for food posing a serious risk to human health that the food

may be classed as failing food.[66]

The Bill specifically provides that none of the

determinations under section 15 of the Imported Food Control Act,

whether by way of holding order, extension of a holding order or revocation of

a holding order are legislative instruments.[67]

Importantly, nothing in the Bill links the decisions made

under section 15 to section 42 of the Imported Food Control Act which

provides that certain decisions are reviewable decisions.

Scrutiny of

Bills Committee

The Scrutiny of Bills Committee expressed concern that the

decision to extend a holding order in respect of food posing a serious risk to

human health is not subject to merits review.[68]

It noted that the Explanatory Memorandum provides that proposed subsection

15(4) ‘has been inserted to enable continued protection of human health

until the appropriate testing regime on the food for the particular hazard

and/or adequate risk management strategies can be implemented in relation to

the food’.[69]

The Committee also noted the comment in the Explanatory

Memorandum that ‘it is intended that the decision maker for an order under new

subsection 15(3) of the Act will not be the same decision maker for, if

applicable, a decision to extend the order under new subsection 15(4) of the

Act’.[70]

However, this is not specified in the Bill.

That being the case, the Scrutiny of Bills Committee

recommended that the Bill be amended to ensure that it is a legislative

requirement that the decision to extend the period of a holding order is made

by a different decision-maker to that who made the original holding order. The

Committee has sought the Minister's response in relation to this.[71]

Classification

of food

Commencement

The provisions in Part 3 of the Bill commence on the day

after Royal Assent.

Key

provisions

Section 16 of the Imported Food Control Act provides

that the particulars of the IFIS may be set out in Regulations. (See the

discussion under the heading ‘Imported Food Inspection Scheme’ above.) The Bill

expands the matters which may be particularised in the Regulations.

First, item 13 of the Bill repeals and replaces

existing paragraph 16(2)(a) and item 2 inserts proposed subparagraph

16(2)(a)(iia). Together they operate so that, in addition to making orders identifying

food of particular kinds as food that must be inspected, or inspected and

analysed,[72]

the Minister may also make Regulations:

- identifying

food of particular kinds as food that must be covered by a recognised

foreign government certificate

- identifying

food of particular kinds as food that must be covered by a recognised food

safety management certificate or

- classifying

food of particular kinds into particular categories.

If a food is classified as being in a particular category,

the Regulations may specify the percentage of the food in that category that

must be referred by an officer of Customs for inspection, or inspection and

analysis, under the Food Inspection Scheme.[73]

In addition the Regulations may empower the Secretary to

make an order about food that is classified into a particular category and is

of a particular kind, requiring a percentage of food of that kind to be

referred by an officer of Customs for inspection, or inspection and analysis,

under the Scheme.[74]

The order is not a legislative instrument.[75]

The order and any revocation of that order are to be published on the

Department’s website.[76]

Second, item 14 of the Bill inserts proposed

paragraph 16(2)(ba) into the Imported Food Control Act so that the Secretary

may make an order about food that is classified into a particular category and

is of a particular kind specifying the incidence of inspection, or inspection

and analysis attaching to the food and specifying the rate at which samples

must be taken for inspection. The order is not a legislative instrument.[77]

The order and any revocation of that order are to be published on the

Department’s website.[78]

The effect of the order is that food which is classified

into a particular category and is of a particular kind may be subject to an

increased rate of inspection or sampling ‘proportionate to the likelihood or

seriousness of the risk to human health’ which it poses.[79]

Recognition

of foreign country’s food safety system

Commencement

The provisions in Part 4 of the Bill commence on the day

after Royal Assent.

Key

provisions

The provisions of items 17–20 of the Bill amend

section 16 of the Imported Food Control Act to allow for the recognition

of a foreign country’s food safety system. According to the Explanatory

Memorandum to the Bill the recognition of a foreign country’s food safety

system ‘occurs only where that foreign country’s food safety system achieves

food safety outcomes that ensures determined food from that country does not

pose a risk to human health’.[80]

Proposed paragraph 16(2)(ac) allows the Minister to

make an order in respect of food classified into a particular category imported

from a country specified in the order setting out the percentage of all such

food (with or without exceptions) or the percentage of food of a particular

kind that is to be referred by an officer of Customs for inspection, or

inspection and analysis, under the Scheme.

Proposed paragraph 16(2)(bb) empowers the Minister

to make an order in respect of food classified into a particular category

imported from a country specified in the order setting out the percentage of

all such food (with or without exceptions) or the percentage of food of a

particular kind that is to be inspected, or inspected and analysed, under the

Scheme.

In either case, the percentage specified in the order must

be less than five percent (including zero).[81]

The Minister must not make either of the types of orders in

relation to a particular country unless the Minister is satisfied:

- there

is an agreement in force between Australia and that country and

- the

agreement is based on an assessment of the food safety systems of Australia and

that country which concluded that Australia and that country have equivalent

food safety systems and conduct equivalent monitoring of the food they

regulate.[82]

An order made under these provisions is a legislative

instrument.[83]

Enforcement

Commencement

The provisions in Part 5 of the Bill commence on the 28th day

after Royal Assent.

Key

provisions

Part 5 of the Bill contains the following:

Providing criminal and civil

remedies allows flexibility to respond to contraventions of the Imported

Food Control Act, with remedies proportionate to the seriousness of

the conduct. A criminal offence must be proved ‘beyond reasonable doubt’ and

results in a criminal record, whereas contravention of a civil penalty

provision is proved on the ‘balance of probabilities’ and does not result in a

criminal conviction. The period of imprisonment specified in the updated

offences is the same as for the offences as currently drafted.

Updated offences

Item 23 of the Bill repeals and replaces sections

8-9 of the Imported Food Control Act which give rise to criminal

offences only. The replacement offence provisions incorporate both the existing

fault-based offences as well as corresponding strict liability offences, for

which there is no requirement for proof of fault.[84]

Proposed section 8 deals with importation offences.

Proposed subsection 8(1) deals with food that does not meet applicable

standards (other than the labelling standard). Under that subsection, a person

commits an offence if the person imports food into Australia to which the Imported

Food Control Act applies and the food does not meet applicable standards—that

is, the standards made by FSANZ. In that case, the maximum penalty is imprisonment

for 10 years. Those same circumstances may, in the alternative, give rise to an

offence of strict liability for which the maximum penalty is 60 penalty units.[85]

Proposed subsection 8(3) deals with food that poses

a risk to human health. Under that subsection a person commits an offence if

the person imports food into Australia to which the Imported Food Control

Act applies and the person knows that the food poses a risk to human

health. In that case, the maximum penalty is imprisonment for 10 years. For the

purposes of that subsection, the person is taken to have known that the food

posed a risk to human health if the person ought reasonably to have known that

the food posed that risk, having regard to the person’s abilities, experience,

qualifications and other attributes and all the circumstances surrounding the

alleged contravention.[86]

In the alternative, the same circumstances give rise to an

offence of strict liability for which the maximum penalty is 60 penalty units.[87]

Proposed section 8A deals

with labelling offences. A person commits a fault‑based offence where

food is imported into Australia to which the Act applies, the person deals

with the food[88]

and the food does not meet applicable standards relating to information on

labels for packages containing food. The maximum penalty is imprisonment for 10

years.[89]

In the alternative, the same circumstances may give rise to an offence of

strict liability—the maximum penalty for which is 60 penalty units.[90]

Importantly, there is an exception to this general rule.

It does not apply to dealing with food in order to alter or replace the label

on the package containing the food so that it meets applicable standards

relating to information on labels for packages containing food.[91]

Proposed section 9 relates to dealings with examinable

food. Proposed subsection 9(1) provides that a person commits an offence

if the person deals with examinable food in a particular manner and each of the

following is satisfied:

- the

person knows that the food has been imported into Australia

- the

person knows that a food control certificate has not been issued in

respect of the food[92]

- the

person has not obtained the approval of an authorised officer to deal with the

food in that manner

- the

person is not dealing with the food in that manner in accordance with a

compliance agreement and

- the

person is neither an officer of Customs, nor an authorised officer, acting in

the course of his or her duties.

Those circumstances give rise to a fault-based offence,

the maximum penalty for which is imprisonment for 10 years.

Proposed subsection 9(2) gives rise to an offence

of strict liability in similar circumstances—absent the element of knowledge.

In that case, the maximum penalty is 60 penalty units.[93]

Proposed subsections 9(3) and (4) create both a fault-based

offence and an offence of strict liability for dealing with food where there is

no imported food inspection advice. Proposed subsections 9(6) and (7) create

both fault-based and strict liability offences for dealing with failing food.

In either case the maximum penalty for the fault-based offence is imprisonment

for 10 years and the maximum penalty for the offence of strict liability is 60

penalty units.[94]

Each of the offences in proposed section 9 of the Bill

reflects existing offences. However, the drafting of the circumstances giving

rise to each of the offences is more specific. This will assist in determining

whether any criminal prosecution should take place.

New civil

penalty provisions

Item 24 of the Bill inserts proposed section 9A into

the Imported Food Control Act to create civil penalty provisions for:

- importing

food that does not meet applicable standards (where those standards do not

relate to information on labels for packages containing food)[95]

- importing

food into Australia that poses a risk to human health[96]

- importing

food into Australia where the person deals with the food and the food does not

meet applicable standards relating to information on labels for packages

containing food[97]

- dealing

with examinable food that has been imported into Australia where a food control

certificate has not been issued in respect of the food; the person has not

obtained the approval of an authorised officer to deal with the food in that

manner; and the person is not dealing with the food in accordance with a

compliance agreement[98]

- dealing

with examinable food that has been imported into Australia for which a food

control certificate has been issued; where an imported food inspection

advice has not been issued and the approval of an authorised officer to deal

with the food in that manner has not been given; and where the person is not

dealing with the food in accordance with a compliance agreement[99]

- dealing

with examinable food that has been imported into Australia; for which a food

control certificate has been issued and the food has been identified as failing

food; where the person does not have approval to deal with the food in

that manner and is not permitted nor required to deal with the food in that

manner under the imported food inspection advice.[100]

In each of the circumstances outlined above, the maximum

civil penalty payable is 120 penalty units.[101]

The Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill provides the rationale for introducing

civil penalties as follows:

Civil penalties provisions have been introduced as one

component of differentiated enforcement provisions, which give greater

flexibility and more opportunity to encourage non-compliant food importers to become

compliant.[102]

Enforcement of the civil penalty provisions will be

subject to the terms of proposed section 24 which is discussed below.

Enforcement

under the Regulatory Powers Act

Item 25 of the Bill repeals and replaces sections 21–32

of the Imported Food Control Act which relate to enforcement of the Act.

The Bill inserts a suite of enforcement provisions that trigger the operation

of the Regulatory Powers Act, which was enacted to provide for

uniformity of enforcement provisions across Commonwealth statutes.

Monitoring

powers

Proposed subsections 22(1) to (3) of the Imported

Food Control Act provide:

- all

provisions of the Act and any regulations or orders made under the Act[103]

- information

given in compliance with the Act, regulations or orders and

- provisions

of a compliance agreement[104]

are subject to monitoring under Part 2 of the Regulatory

Powers Act.

The monitoring

powers (set out at section 19 of the Regulatory Powers Act)

which may be exercised on premises that an authorised person[105]

has entered under warrant or consent, include the power to:

- search the premises and any thing on the premises

- examine or observe any activity conducted on the premises

- inspect, examine, take measurements of or conduct tests on any

thing on the premises

- make any still or moving image or any recording of the premises

or any thing on the premises

- inspect any document on the premises

- take extracts from, or make copies of, any such document

- take

onto the premises such equipment and materials as the authorised person requires

in order to exercise powers in relation to the premises

- operate

electronic equipment on the premises, to put relevant data in documentary form or

copy the data onto a device and remove the documents or device from the

premises[106]

-

secure electronic equipment where an authorised person enters

premises under a monitoring warrant[107]

- secure

a thing for a period of 24 hours in circumstances where the thing is found

during the exercise of monitoring powers on the premises and an authorised

person believes on reasonable grounds that it relates to the contravention of a

related provision.[108]

These powers may only be exercised to:

- determine

whether the Imported Food Control Act (and regulations and orders made

under that Act) or a compliance agreement is being complied with and/or

- determine

whether information supplied under the Act, regulations, orders or a compliance

agreement is correct.[109]

Proposed subsections 22(12) and (13) of the Imported

Food Control Act provide additional monitoring powers, being the power to take

and keep samples of any thing at any premises entered under the powers set out

above. An authorised person executing a monitoring warrant, or a person

assisting the authorised person, may use such force as is reasonable and

necessary in the circumstances against things. However, this does not extend to

the use of force against a person.[110]

Issuing a monitoring warrant

A monitoring warrant may be issued if the issuing

officer[111]

is satisfied that it is reasonably necessary for one or more authorised persons

to have access to premises for the purpose of determining whether a provision

that is subject to monitoring has been, or is being, complied with or that

information subject to monitoring is correct.[112]

In that case the relevant warrant must do all of the following:

describe the premises to which the warrant relates

- state that the warrant is issued under section 32 of the Regulatory

Powers Act

- state the purpose for which the warrant is issued

- authorise

one or more authorised persons (whether or not named in the warrant) from time

to time while the warrant remains in force to enter the premises and to

exercise the monitoring powers

- state whether entry is authorised to be made at any time of the

day or during specified hours of the day and

- specify

the day (not more than three months after the issue of the warrant) on which

the warrant ceases to be in force.[113]

An authorised officer may enter premises and exercise the

monitoring powers only if the occupier of the premises has consented to the

entry, or the entry is made under a monitoring warrant.[114]

Investigation powers

Proposed section 23 of the Imported Food Control

Act sets out the provisions that are subject to investigation under Part 3

of the Regulatory Powers Act. They are:

- an offence against the Imported Food Control Act

- a civil penalty provision under the Imported Food Control Act

or

-

an offence against the Crimes Act or the Criminal Code

that relates to the Imported Food Control Act.

Part 3 of the Regulatory Powers Act applies to the evidential

material in respect of the above.[115]

Evidential material is material relevant to the criminal

offences and civil penalty provisions specified above.[116]

Proposed subsection 23(3) of the Imported Food

Control Act provides that the Secretary of the Agriculture Department and

an APS employee who is an ‘authorised officer’ under section 40 of that Act is

an authorised applicant and an authorised person

under Part 3 of the Regulatory Powers Act. Authorised applicants and

authorised persons can exercise various powers under Part 3. The powers of

authorised persons, including the power to enter premises under an

investigation warrant, are set out in Division 2 of Part 3. An authorised

applicant is able to apply for an investigation warrant under Division 6 of

Part 3.

Proposed subsection 23(5) provides that the

Secretary is the relevant chief executive under the Regulatory Powers

Act. This means that the Secretary may exercise certain powers under Part

3, such as such as disposing of items that were seized from premises entered

under that Part.[117]

The investigation powers (set out at section

49 of the Regulatory Powers Act) which may be exercised on premises that

an authorised person has entered under warrant or consent, include the power

to:

- where

the occupier consents to entry—search the premises and any thing on the

premises for the evidential material the authorised person suspects on

reasonable grounds may be on the premises

- where

the entry is under warrant—search the premises and any thing on the premises

for the kind of evidential material specified in the warrant and to seize

evidential material of that kind if the authorised person finds it on the

premises

-

inspect, examine, take measurements of, or conduct tests on, the

evidential material

- make any still or moving image or any recording of the premises

or evidential material

- take

onto the premises such equipment and materials as the authorised person requires

for the purpose of exercising powers in relation to the premises

- operate

electronic equipment on the premises, to put relevant data in documentary form or

copy the data onto a device and remove the documents or device from the

premises. If the entry is under warrant, the equipment may be seized[118]

-

secure electronic equipment where an authorised person enters

premises under an investigation warrant[119]

Similar to the provisions about monitoring powers, proposed

subsections 23(9) and (10) of the Imported Food Control Act provide for

additional investigation powers—being the power to take and keep samples of any

thing at the premises entered into by consent and under warrant. In addition, an

authorised person may be accompanied by another person to assist him or her in

exercising an investigation power.[120]

An authorised person or assisting person may use such force as is reasonable

and necessary in the circumstances against things. However, this does not

extend to the use of force against a person.[121]

Issuing an investigation warrant

Where an authorised person suspects on reasonable grounds

that there may be evidential material on any premises, he, or she, may enter

the premises and use investigation powers so long as the occupier consents or

the authorised person has an investigation warrant.[122]

The provisions in Part 3 of the Regulatory Powers Act set out the

requirements for applying for an investigation warrant and its contents.[123]

Scrutiny of

Bills Committee

The Scrutiny of Bills Committee expressed its concern that

proposed subsections 22(14) and 23(11) provide that an authorised

officer may be assisted ‘by other persons’ in exercising powers or performing

functions or duties in relation to monitoring and investigation—but that the Explanatory

Memorandum does not describe the categories of ‘other persons’ who may be

granted such powers.[124]

The Committee queried the Explanatory Memorandum’s statement that the

provisions preserve the effect of existing section 32, repealed by item 25

of the Bill, and noted that this existing section is limited to requiring the

occupier of premises entered to provide reasonable assistance to the officer.[125]

The scope of proposed subsections 22(14) and 23(11) is not similarly

limited.

As the powers granted to ‘other persons’ are coercive in

nature the Scrutiny of Bills Committee has requested the Minister’s advice as

to the following:

- why

it is necessary to confer monitoring and investigatory powers on any ‘other

person’ to assist an authorised officer and

- whether

it would be appropriate to amend the Bill to require that any person assisting

an authorised officer be confined to the occupier of the relevant premises or

to require the person assisting have specified skills, training or experience.[126]

Enforceable

civil penalty provisions

Proposed section 24 of the Imported Food Control

Act provides that each of the civil penalty provisions is enforceable under

Part 4 of the Regulatory Powers Act. Accordingly a civil penalty

provision may be enforced by obtaining an order for a person to pay a pecuniary

penalty for the contravention of the provision.

Proposed subsection 24(2) provides that the

Secretary is an authorised applicant in relation to the civil

penalty provisions. This allows the Secretary to apply to the Federal Court of

Australia, the Federal Circuit Court of Australia or a court of a state or territory

that has jurisdiction under the Imported Food Control Act, for a civil

penalty order requiring a person who is alleged to have contravened a civil

penalty provision, to pay the Commonwealth a pecuniary penalty.[127]

The authorised applicant must make the application within four

years of the alleged contravention.[128]

In determining the pecuniary penalty, the court must take

into account all relevant matters, including:

- the

nature and extent of the contravention

- the

nature and extent of any loss or damage suffered because of the contravention

- the

circumstances in which the contravention took place and

- whether

the person has previously been found by a court (including a court in a foreign

country) to have engaged in any similar conduct.[129]

A relevant court may make a single civil penalty order

against a person for multiple contraventions of a civil penalty provision if

proceedings for the contraventions are founded on the same facts, or if the

contraventions form, or are part of, a series of contraventions of the same or

a similar character. However, the penalty must not exceed the sum of the

maximum penalties that could be ordered if a separate penalty were ordered for

each of the contraventions.[130]

Other enforcement options

The Bill also inserts provisions into the Imported Food

Control Act which will enable the Department to take other enforcement

actions which are more educative than punitive in nature.

Infringement

notices

One of these options is to issue an infringement notices.

The provisions about infringement notices are governed by Part 5 of the Regulatory

Powers Act. They apply to strict liability offences and civil penalty

provisions of the Imported Food Control Act. Proposed subsection

25(2) provides that both the Secretary and an APS employee in the

Department appointed by the Secretary (under subsection 40(1) of the

Imported Food Control Act) are infringement officers. The

Secretary is also the relevant chief executive officer under Part

5, which allows him or her to exercise powers such as allowing a person more

time to pay an infringement notice amount or withdrawing an infringement

notice.[131]

The Secretary may, in writing, delegate to an SES employee, or acting SES

employee, in the Department the Secretary’s powers and functions under

Part 5 of the Regulatory Powers Act in relation to infringement

notices.[132]

If an infringement officer

believes on reasonable grounds that a person has contravened a provision

subject to an infringement notice, he or she may give to the person an

infringement notice for the alleged contravention. That notice must be given

within 12 months after the day on which the contravention is alleged to have

taken place.[133]

The amount payable under the notice must be the lesser of: one-fifth of the

maximum penalty that a court could impose on the person for that contravention;

or 12 penalty units for an individual or 60 penalty units for a body corporate.[134]

Enforceable

undertakings

The other option is to accept an enforceable undertaking. A

provision is enforceable under Part 6 of the Regulatory Powers

Act if it is an offence against the Imported Food Control Act or a

civil penalty provision of the Imported Food Control Act.[135]

Proposed subsection 26(2) provides that the

Secretary is an authorised person for the purposes of Part 6

of the Regulatory Powers Act. This allows the Secretary to accept an

undertaking relating to compliance with an enforceable provision

of the Imported Food Control Act.

That undertaking may be enforced by a relevant court—that

is, the Federal Court of Australia, the Federal Circuit Court of Australia or a

court of a state or territory that has jurisdiction in relation to matters

under the Imported Food Control Act. The court may make any order that

it considers appropriate, include an order directing compliance, an order

requiring any financial benefit from the failure to comply to be surrendered

and an order for damages.[136]

New Part 4—other matters

Part 4 of the Imported Food Control Act currently commences

at section 35A and is titled ‘miscellaneous’.

The Bill retitles Part 4 as ‘other

matters’,[137] inserts new provisions so that it commences at proposed section 32A

and inserts a simplified outline to enhance readability. The revamped Part 4 deals

with various matters, such as evidence of analysts of food, the making of

compliance agreements and the use, disclosure and publication of information

obtained under Imported Food Control Act.

Power to require information or documents

Item 27 of the Bill inserts proposed section 34A

into the Imported Food Control Act so that

where the Secretary believes on reasonable grounds that a person has

information or documents relevant to the operation of the Imported Food Control Act, the Secretary may, by

written notice, require the person to give an authorised officer the

information or produce the documents specified in the notice within the period

specified in the notice. That period must be at least 14 days after the notice

is given—although a shorter period may be specified if the Secretary considers

it necessary to do so because the information or documents relate to food that

the Secretary is satisfied may pose a serious risk to human health.[138]

A person who fails to comply with a notice that has been given under proposed

section 34A commits an offence of strict liability. The maximum penalty is 60

penalty units.[139]

Record

keeping

Commencement

The amendments in Part 6 of the Bill commence on the

earlier of a single day to be fixed by Proclamation or 12 months after

Royal Assent.

Key

provisions

Item 37 of the Bill inserts

proposed Part 3A—Record-keeping into the Imported Food Control Act.

The principal requirements of proposed

Part 3A are as follows:

- if

food to which the Imported Food Control Act applies is imported into

Australia, the owner of the food at the time of the importation must keep

records containing the information which is determined in a legislative instrument

made by the Secretary, for a period of five years. A person commits an offence

of strict liability if the person fails to keep records as required.[140]

The maximum penalty for a contravention is 60 penalty units[141]

- the

Secretary may, by written notice, require a person who must keep records to produce

them to the Secretary, within the time and in the manner specified in the

notice.[142]

Generally, the period specified in the notice must be at least 14 days after

the notice is given.[143]

However, a shorter period may apply if the Secretary considers it necessary—because

the records relate to food that may pose a serious risk to human health.[144]

A person commits a criminal offence if he, or she, does not comply with a

notice that has been given.[145]

The maximum penalty for contravention of this provision is six months

imprisonment.[146]

Use and

disclosure of information

Commencement

The provisions in Part 8 of the Bill commence on the day

after Royal Assent.

Key

provisions

Item 43 of the Bill inserts proposed section 42A

into the Imported Food Control Act.

Use of

information

The Bill provides that an Australian Public Service (APS)

employee in the Department of Agriculture and Water Resources may use

information (including personal information[147])

obtained under the Imported Food Control Act for any purpose of the Act.[148]

Disclosure

of information

The Bill empowers the Secretary to disclose information

(including personal information) obtained under the Imported Food Control

Act to a range of entities if the Secretary is satisfied that the

disclosure of the information to that entity is necessary for the entity to perform

or exercise any of its functions, duties or powers.[149]

The Secretary may also disclose information (including

personal information) obtained under the Imported Food Control Act to a

department of the government of a foreign country or an agency, authority or

instrumentality of the government of a foreign country provided that the

Secretary is satisfied that the disclosure of the information is necessary for

that department, agency, authority or instrumentality to perform or exercise

any of its functions, duties or powers.[150]

However, such a disclosure must not be made unless the Secretary is satisfied

that the disclosure is in connection with food imported into Australia and that

the food may pose a risk to human health.[151]

Finally, the Bill requires the Secretary to make written guidelines

(published on the Department’s website) to which he, or she, must have regard

to before disclosing information to a foreign country or to an agency,

authority or instrumentality of the government of a foreign country.[152]

The Secretary must consult the Information Commissioner before making the

guidelines.[153]

The guidelines are not a legislative instrument.[154]

Scrutiny of

Bills Committee

The Scrutiny of Bills Committee noted the comments in the

Explanatory Memorandum in relation to the making of guidelines in consultation

with the Australian Information Commissioner.

However, the Committee stated that it was unclear ‘why the

guidelines, which become a mandatory consideration for exercising a power that

affects the right to privacy, should not be a legislative instrument and,

therefore, subject to parliamentary scrutiny and disallowance’ [and] ‘why the

development of the guidelines is limited to the exercise of the Secretary's

power in disclosing information to a foreign country, and not in relation to

disclosing information to other Commonwealth agencies and State, Territory or

local governments’.[155]

The being the case, the Scrutiny of Bills Committee has

requested the Minister's advice in relation to those matters.[156]

Other

amendments

Commencement

The provisions in Part 9 of the Bill commence on the day

after Royal Assent.

Key

provisions

Items 45 and 47 of the Bill

amend the definition of food in the Imported Food Control Act so that it

is in equivalent terms to those used in the FSANZ Act.[157]

Proposed section 3A provides that food includes:

(a) any substance or thing of a kind used, capable of being

used, or represented as being for use, for human consumption (whether it is

live, raw, prepared or partly prepared); and

(b) any substance or thing of a kind used, capable of being

used, or represented as being for use, as an ingredient or additive in a

substance or thing referred to in paragraph (a); and

(c) any substance used in preparing a substance or thing

referred to in paragraph (a); and

(d) chewing gum or an ingredient or additive in chewing

gum, or any substance used in preparing chewing gum; and

(e) any substance or thing declared to be a food under a

declaration in force under section 6 of the Food Standards Australia

New Zealand Act 1991.

(It does not matter whether the substance, thing or chewing

gum is in a condition fit for human consumption.)

Concluding comments

The Bill makes significant changes to the Imported Food

Control Act by expanding the power of the Secretary to make holding orders.

Under the Bill this power will also apply to food posing a serious risk to

human health. In addition, Part 3 of the Bill expands the matters about which

the Minister may make Regulations. This is intended to apply to the various

classifications of imported food so that particular foods which pose new and

emerging risks can be subject to a more intensive inspection regime.

The Bill also allows for the recognition of a foreign

country’s food safety regulatory system where it is equivalent to Australia's

food safety system—so that food inspection may be better targeted.

To complement these new powers, Part 5 of the Bill sets

out increased enforcement measures—including civil penalty provisions and

infringement notices.

The Scrutiny of Bills Committee has suggested minor, but

valuable, amendments to the Bill—in particular the need to make clear that the

person who makes a decision to impose a holding order is different from the

person who makes a decision to extend the order.

[1]. Department

of Agriculture and Water Resources (DoAWR), ‘Strengthening the

management of imported food safety’, DoAWR website, 9 August 2017.

[2]. Food

Regulation Agreement, 3 July 2008.

[3]. Agreement

between the Government of Australia and the Government of New Zealand

concerning a Joint Food Standards System, 5 December 1995.

[4]. Food

Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ), ‘Food standards

code’, FSANZ website.

[5]. Australia New Zealand Foods

Standards Code, Standard

3.1.1: Interpretation and Application; Australia New Zealand Foods

Standards Code, Standard

3.2.1: Food Safety Programs; Australia New Zealand Foods Standards Code, Standard 3.2.2: Food

Safety Practices and General Requirements; Australia New Zealand Foods

Standards Code, Standard

3.2.3: Food Premises and Equipment.

[6]. Food Act

2006 (Qld); Food Act

2003 (NSW); Food Act

1984 (Vic); Food Act

2003 (Tas); Food Act

2001 (SA); Food Act

2008 (WA); Food Act

2001 (ACT); Food Act

(NT).

[7]. FSANZ,

‘Food

recalls’, FSANZ website, October 2016.

[8]. Senate

Community Affairs Committee, Answers to Questions on Notice, Health Portfolio,

Budget Estimates 2015–16, Question

SQ15–000400.

[9]. The

Australian Consumer Law is located at Schedule 2 of the Competition and

Consumer Act 2010.

[10]. Consumer

goods are defined in clause 2 of the Australian Consumer Law as goods

that are intended to be used, or are of a kind likely to be used, for personal,

domestic or household use or consumption, and includes any such goods that have

become fixtures since the time they were supplied if (a) a recall notice for

the goods has been issued or (b) a person has voluntarily taken action to

recall the goods.

[11]. C

Baggoley (Chief Medical Officer), Hepatitis

A linked to frozen berries, media release, 26 February 2015.

[12]. S

Santow, ‘Poor

hygiene in China thought to be cause of hepatitis A outbreak linked to imported

frozen berries’, ABC News, (online edition),

16 February 2015.

[13]. F

Nash (Assistant Minister for Health), Action

on Hepatitis A, media release, 18 February 2015.

[14]. B

Joyce (Minister for Agriculture), Update

on situation around imported berries and Hepatitis A, media release, 16

April 2015.

[15]. DoAWR,

Imported

food reforms: decision regulation impact statement, DoAWR, Canberra,

2016, p. 16, (references removed).

[16]. J

Ross, ‘Tests

fail to keep up with food imports’, The Australian, 24 February

2015, p. 2; R Harris, ‘Holes

in tests for safe food’, The Adelaide Advertiser, 11 June

2015, p. 2.

[17]. Imported

Food Control Act, section 2A.

[18]. Ibid.,

section 7.

[19]. Ibid.,

section 8.

[20]. Ibid.,

subsection 3(2).

[21]. Risk

food is food that FSANZ has advised the Minister has the potential to

pose a high or medium risk to public health. Imported Food Control Regulations,

section 9.

[22]. Imported

Food Control Regulations, section 10; Imported Food Control Act, section

35A. Food Import Compliance Agreements (FICAs) are a co-regulatory assurance