Bills Digest no. 45,

2016–17

PDF version [1204KB]

Kai Swoboda

Economics Section

23

November 2016

Contents

The Bills Digest at a glance

Purpose and structure of the Bills

Background

Overview of superannuation tax

arrangements

Existing arrangements

Recent changes

Policy development

2016–17 Budget announcement

2016 election policy and policy

adjustment

Treasury consultation

Emergence of concerns

Sustainability

Value of superannuation tax

concessions

Impact of an ageing population

Fairness

Rudd/Gillard Governments

Abbott Government

Turnbull Government

Key superannuation figures and

information

Value of superannuation savings

The importance of superannuation for

household savings

Individual superannuation savings and

contributions

Committee consideration

Senate Economics Committee

Senate Standing Committee for the

Scrutiny of Bills

Policy position of non-government

parties/independents

Australian Labor Party

2015 announcement

Subsequent August announcement

Subsequent November announcement

Other parties and independents

Australian Greens

Liberal Democrats

One Nation

Nick Xenophon Team

Which elements of the package have

bipartisan support?

Position of major interest groups

Superannuation industry groups

Professional bodies

Thinktanks/research groups

Other groups

Financial implications

Statement of Compatibility with Human

Rights

Key issues and provisions

How many people are affected by the

proposed changes?

Schedule 1—Transfer balance cap

Commencement

Key provisions

Is a $1.6 million cap too high,

too low, or about right?

Application to defined benefit fund

members

Certain factors given special

treatment in relation to the $1.6 million cap

Schedule 2—Concessional

superannuation contributions and income threshold for the imposition of an

additional 15 per cent contributions tax

Commencement

Key provisions

Concessional contributions cap

Lower the income threshold for the

imposition of an additional 15 per cent contributions tax from

$300,000 to $250,000

Table 3: Tax assessments for

taxpayers liable for the additional 15 per cent tax on concessional

contributions, 2013–14 to 2015–16

Schedule 3—Non-concessional

contributions

Commencement

Key provisions

Schedule 4—Low income superannuation

tax offset

Commencement

Key provisions

Schedule 5—Deducting personal

contributions

Commencement

Key provisions

Schedule 6—Unused concessional cap

carry forward

Commencement

Key provisions

Schedule 7—Tax offsets for spouse

contributions

Commencement

Key provisions

Schedule 8—Innovative income streams

and integrity

Commencement

Key provisions

Remove the earnings tax exemption in

respect to transition to retirement income streams

Extend the earnings tax exemption to

new ‘lifetime’ products

Schedule 9—Anti-detriment provisions

Commencement

Key provisions

Schedule 11—Dictionary

Date introduced: 9

November 2016

House: House of

Representatives

Portfolio: Treasury

Commencement: Various

dates as set out in the body of this Bills Digest

Links: The links to the Bills,

their Explanatory Memoranda and second reading speeches can be found on the

home pages for the Treasury

Laws Amendment (Fair and Sustainable Superannuation) Bill 2016 and the Superannuation

(Excess Transfer Balance Tax) Imposition Bill 2016, or through the Australian

Parliament website.

When Bills have been passed and have received Royal Assent,

they become Acts, which can be found at the Federal Register of Legislation

website.

All hyperlinks in this Bills Digest are correct as

at November 2016.

The Bills Digest at a glance

Suite of legislation

The Government has introduced three Bills as part of a

suite of legislation:

This Bills Digest deals with only the first two of those

three Bills. The third Bill is the subject of a separate Bills Digest.

Purpose of the Bills

- The Bills include amendments to various tax and superannuation

laws to implement most of the elements included in the Government’s 2016–17

Budget ‘Superannuation Reform Package’, as modified by the Government in

September 2016.

Measures included in the Bills

- The Bills include the necessary amendments to implement most of

the key measures as outlined in September 2016, including providing for an

indexed $1.6 million cap on tax-free earnings on superannuation earnings,

reducing contributions caps to limit monies paid into superannuation, reimbursing

tax paid on superannuation contributions by low income earners and increasing

tax rates on superannuation contributions for higher income earners.

Policy rationale

- The Government uses a number of different arguments to support

the introduction of the measures. These include improving ‘fairness’,

‘sustainability’, ‘flexibility’ and ‘integrity’.

- The broader backdrop to the package of measures is to provide

savings to improve the budget position.

Policy position of non-government parties

- The ALP supports many elements of the package of measures and has

proposed amendments to several measures. The ALP opposes two measures relating

to removing restrictions to allow all individuals up to the age of 75 to claim

an income tax deduction for contributions and allowing catch-up concessional

contributions for individuals. That said, the ALP has indicated that it will ‘facilitate’

the passage of the Bills through the Parliament.

- It is unclear what the position of other parties and independents

will be on the Bills.

Stakeholder views

- The package of measures has the broad support of superannuation

industry groups, although certain elements, such as the lower concessional

contributions caps, are opposed by some industry groups.

Key issues

-

Issues relating to ‘fairness’ and ‘sustainability’ of

superannuation tax concessions have been on the policy agenda for a number of

years. The proposed measure to cap tax-free earnings on superannuation at a

balance of $1.6 million and to limit other superannuation contributions

using this balance provides a basis for reducing the tax concession available

to higher income earners.

- This Digest includes discussion of schedules of the Bill for

which analysis had been completed at the time of publication. An updated Bills

Digest that includes those schedules not analysed here, may be provided at a

later date.

Purpose and

structure of the Bills

The purpose of the suite of Bills is to implement the

Government’s 2016–17 ‘Superannuation Reform Package’ of measures, as modified

by the Government in September 2016. Most of the amendments apply to the Income Tax

Assessment Act 1997 (ITAA 1997).

The Treasury Laws Amendment (Fair and Sustainable

Superannuation) Bill 2016 (the main Bill) includes the amendments to implement

the following measures:

- impose

a $1.6 million transfer balance cap on the amount of superannuation capital, to

be indexed in $100,000 increments, that can be transferred to the tax-free

earnings retirement phase of superannuation (Schedule 1)

- reduce

the annual concessional contributions cap to $25,000, to be indexed in $2,500

increments (Schedule 2)

- lower

the income threshold at which an additional 15 per cent tax applies on

concessional superannuation contributions to $250,000 (Schedule 2)

- lower

the non-concessional contributions cap to four times the concessional cap

(initially $100,000) (Schedule 3)

- refund

superannuation contributions tax paid by lower income earners through the low

income superannuation tax offset (Schedule 4)

- remove

the requirement that an individual must earn less than ten per cent of

their income from employment-related activities to be able to deduct a personal

contribution to superannuation and make it a concessional contribution (Schedule

5)

- allow

for catch-up concessional contributions by allowing individuals to carry

forward unused concessional contribution amounts from the previous five years if

they have a total superannuation balance of $500,000 or less (Schedule

6)

- increase

the income threshold for the spouse of a taxpayer from $13,800 to $40,000 at

which the taxpayer can claim a tax offset of up to $540 per year for

superannuation contributions made on behalf of their spouse (Schedule 7)

- remove

the tax exemption for transition to retirement income streams and remove tax

barriers to the development of income stream products such as deferred lifetime

annuities (Schedule 8)

- remove

the so-called ‘anti detriment’ provisions which allow an income tax deduction on

some lump sums paid because of the death of a member for the benefit of their

spouse, former spouse or child, to compensate them for income tax paid by the

fund in respect of contributions made for the member during their lifetime (Schedule

9)

- change

a number of administrative processes relating to the payment of amounts to the

Commissioner of Taxation by superannuation funds relating to certain

superannuation fund members (Schedule 10).

Schedule 11 of the main Bill inserts a number of

key definitions into the ITAA 1997 that relate to the measures.

The purpose of the Superannuation (Excess Transfer Balance

Tax) Imposition Bill 2016 is to specify the tax rate (15 per cent or

30 per cent) that applies to earnings on amounts that exceed an

individual’s transfer balance cap.[1]

This Bills Digest does not provide any commentary or

analysis in relation to the Superannuation (Objective) Bill 2016, which is discussed

in the Explanatory Memorandum for the suite of Bills. The Superannuation

(Objective) Bill 2016 will be covered in a separate Bills Digest.

Background

Overview of

superannuation tax arrangements

Existing arrangements

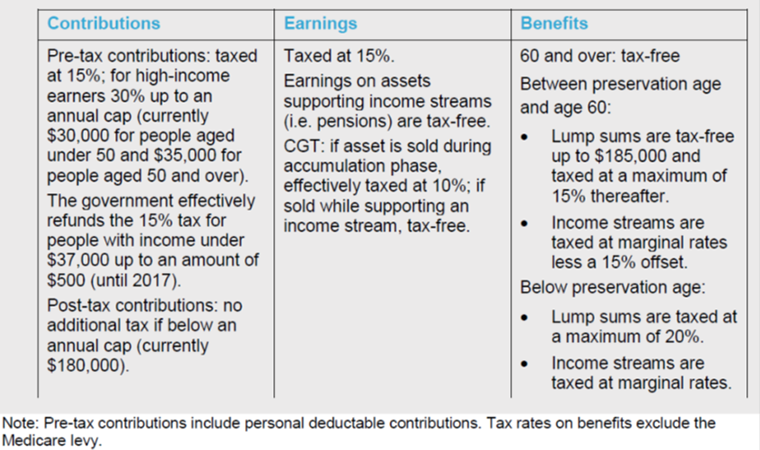

The broad approach to the taxation of superannuation in

Australia is for a 15 per cent tax to be applied to certain contributions,

a 15 per cent tax to be applied to earnings within the fund and for

superannuation benefits to be tax-free from the age of 60. This approach to

taxation is supported by arrangements that limit contributions by employers,

individuals (pre- and post-tax) and the conditions under which superannuation

can be accessed, such as the age at which superannuation can be withdrawn (the

‘preservation age’).

The existing tax treatment for accumulation funds—the more

common type of arrangement where the final benefit to an individual is related

to contributions to the fund and investment earnings of the fund—and the limits

on contributions are outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Tax treatment of superannuation savings: accumulation funds

Source: Australian Government, Re:think:

tax discussion paper: better tax system, better Australia, The

Treasury, Canberra, 30 March 2015, p. 69.

Recent

changes

The existing arrangements have broadly been in place since

July 2007. That said, changes have been made over the past decade, mostly under

the Rudd-Gillard-Rudd Governments, to tax arrangements and the framework

influencing superannuation contributions, including:

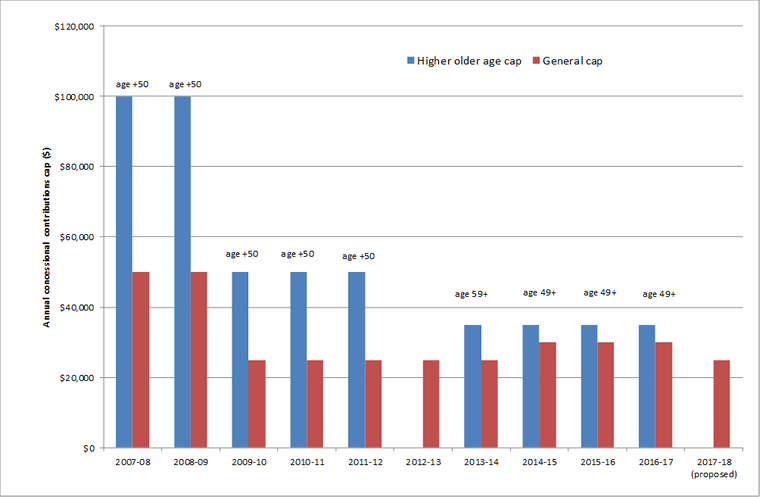

- a

reduction in concessional caps (which are also linked to non-concessional caps

as these are set at six times the value of concessional caps) from

$50,000 for those aged less than 50 and $100,000 for those aged more

than 50 for the 2007–08 financial year to a uniform $25,000 for all ages

in 2012–13. This amount was then increased and age differentiation

re-introduced to be $30,000 for those aged less than 49 and

$35,000 for those aged 49 or more in the 2016–17 financial year[2]

- the

introduction of the low income superannuation contribution (LISC) from the

2012–13 financial year to effectively reimburse into a superannuation fund the

15 per cent contributions tax paid by those on an annual income of

$37,000 or less.[3]

The LISC is legislated to be abolished after the end of the 2016–17 financial

year[4]

- the

introduction of an additional 15 per cent contributions tax from the

2012–13 financial year for individuals earning above a $300,000 income

threshold[5]

- the

scaling back of the government co-contribution (a government contribution to

the superannuation fund of eligible low income earners who make undeducted

personal contributions), from a maximum co‑contribution of $1,500 and to

a lower income threshold of $28,000 in 2004–05 to a maximum of $500 at a lower

income threshold of $36,021 for 2016–17[6]

- an

increase in the employer contribution rate under the superannuation guarantee

scheme from nine per cent in 2012–13 to 9.5 per cent over the period

2014–15 to 2020–21 and then progressively increasing to 12 per cent by 2025–26.[7]

In general terms, these changes have provided some

additional support for lower income earners and reduced, to some extent, the

ability of higher income earners to make additional superannuation

contributions.

Policy

development

2016–17

Budget announcement

The measures included in the suite of Bills were announced

by the Government as part of the 2016–17 Budget. The ten separate

measures—packaged together under the title ‘Superannuation Reform Package’—can be

broadly characterised into three categories: those that limit tax concessions

for higher income earners or those individuals with high superannuation balances;

those that support the ‘integrity’ of superannuation tax concessions; and

measures that support low income earners or provide greater flexibility to make

additional contributions for those who have been unable to do so. The measures

comprised:

- measures

impacting on higher income earners and those with a capacity to make additional

contributions

- introduce

a $1.6 million cap on superannuation balances to limit tax-free investment

earnings for those in the pension phase

- introduce

a lifetime cap of $500,000 for non-concessional superannuation contributions

- apply

a 30 per cent tax on contributions for those earning $250,000 or more (current

threshold $300,000) and reduce the concessional contributions cap to $25,000

(currently $35,000 for those aged 49 and over and $30,000 for those aged less

than 49)

- 'integrity'

measures

- remove

the anti-detriment provision in respect of death benefits from superannuation.

This essentially provided for a refund of contributions tax paid in certain

circumstances

- remove

the tax exemption on earnings of assets supporting Transition to Retirement

Income Streams, which allows a tax-free drawdown from superannuation whilst

continuing to work

- measures

supporting low income earners or allowing for limited additional or more

flexible contributions arrangements

- introduce

the Low Income Superannuation Tax Offset to essentially continue the existing

Low Income Superannuation Contribution scheme that compensates low income

earners for the 15 per cent contributions tax for those earning less than

$37,000

- allow

catch-up concessional contributions for individuals with unused amounts within

their annual concessional contributions cap for those with a superannuation

balance of less than $500,000

- remove

restrictions for those aged 65 to 74 from making superannuation contributions

- raise

the threshold for the low income spouse contributions threshold from $10,800 to

$37,000

- remove

restrictions to allow all individuals up to the age of 75 to claim an income

tax deduction for contributions.[8]

The main policy rationale for the introduction of the

package was to better target the existing tax concessions within the context of

broader budget ‘repair’. The Treasurer, Scott Morrison, noted in his budget

speech:

Together with raising your children and owning your own home,

becoming financially independent in retirement, is one of life’s great

challenges and achievements.

We need to ensure that our superannuation system is focussed

on sustainably supporting those most at risk of being dependent on an Age

Pension in their retirement, which is the purpose of these concessions.[9]

2016

election policy and policy adjustment

During the 2016 election campaign and following the election,

the Government was reportedly under pressure from some of its own members to

make changes to some elements of the package, particularly the backdated commencement

of the $500,000 lifetime cap on non-concessional contributions.[10]

On 3 June 2016, the Prime Minister was asked whether the

measures as announced at the 2016–17 Budget were ‘ironclad’. In response, the

Prime Minister noted:

[The superannuation policy as detailed in the May 3 budget]

is absolutely ironclad. Yes, the commitment[s] that we have made in the budget

are our policy. If we are returned we’ll implement those policies. I believe

they are fair. They make the super system, more flexible and more sustainable.

The big beneficiaries are people on lower incomes earning up to $37,000 who

won’t pay tax on their super, women who are out - this applies to men of course

but it mostly applies to women in practise - people who are out of the

workforce for up to five years, they can roll over their concessional entitlements,

concessional contribution caps if you like, and double up on them for five

years to catch up. That’s good for flexibility, particularly good for women.

Older people who currently can’t contribute to super on a concessional basis

after 65 will be able to now, until they’re 75 because obviously many people in

that age bracket continue to work. Independent contractors will be able to

contribute in the same way that employees can. So that’s made it a much fairer,

and more flexible, and sustainable system.[11]

On 15 September 2016, the Treasurer announced

‘improvements’ to the 2016–17 Budget superannuation measures.[12]

Changes to the package included:

- replacing

the $500,000 lifetime non-concessional cap with a reduction in the existing

annual non‑concessional contributions cap from $180,000 per year to

$100,000 per year

- individuals

with a superannuation balance of more than $1.6 million will no longer be

eligible to make non‑concessional (after tax) contributions from 1 July

2017. This limit will be tied and indexed to the transfer balance cap

- not

proceeding with the harmonisation of contribution rules for those aged 65 to 74,

and

- the

commencement date of the proposed catch-up concessional superannuation

contributions will be deferred by 12 months to 1 July 2018.[13]

In the press conference announcing these changes, the

Treasurer responded to questions about the ‘ironclad’ nature of the 2016–17

package of measures, noting:

What I accept is that when you're in Government, you have to

solve problems, you have to work issues and you have to get to conclusions and

that's what we've done today. But importantly, what we took to the Australian

people was to make superannuation fairer, more flexible, to improve its

integrity and to make it more sustainable and make sure it contributes to the

budget task. And we've done all of that. What we've done today is not just to

take a hard issue and drop it and make taxpayers pay for the difference. No. We

have applied a discipline to ourselves in working through this issue fiscally,

which I think should be a model to others. If people want to deal with issues,

and there are other issues we have to deal with as a government, the same rules

will apply. We will make sure what we do washes its face.[14]

Treasury

consultation

The measures that are included in the suite of Bills were part

of a consultation process undertaken by the Treasury over the period September

to October 2016:

- on

7 September 2016, draft legislation and explanatory material was released

relating to the measures for the objective of superannuation, tax deductions

for personal superannuation contributions, improving superannuation balances of

low income spouses, introduction of the LISTO and harmonising contribution

rules for those aged 65-74[15]

- on

27 September 2016, draft legislation and explanatory material was released

relating to the measures for the introduction of the $1.6 million transfer

balance cap, lowering the income threshold to $250,000 for additional tax on

concessional contributions and reducing the concessional contributions cap to

$25,000, allowing catch-up concessional contributions for those with balances

less than $500,000, removing regulatory barriers to innovation in the creation

of retirement income stream products, improving the integrity of transition to

retirement income streams and removing the anti-detriment provision[16]

- on

10 October 2016, draft legislation and explanatory material was released

relating to the measures to lower the annual non-concessional contributions cap

to $100,000 and restrict eligibility to make non‑concessional

contributions to individuals with superannuation balances below $1.6 million.[17]

Emergence

of concerns

Sustainability

Debate about the sustainability of superannuation tax

concessions has emerged from awareness of the cost of superannuation tax

concessions (in terms of revenue foregone) as well as concerns about the impact

of population ageing on the budget.

Value of

superannuation tax concessions

Measured superannuation tax concessions have grown

significantly in recent years. According to Treasury’s most recent annual tax

expenditures statement, the major superannuation tax expenditures—the

concessional taxation of employer contributions and superannuation fund

earnings—were measured to ‘cost’ almost $30 billion in 2015–16 on a

revenue foregone basis.[18]

While there is not universal agreement about how these tax

concessions are calculated,[19]

the expected continued growth in these and other superannuation tax concessions

into the future has nevertheless promoted some policy consideration about

whether such support for superannuation is desirable, particularly in the

context of the Commonwealth’s fiscal position.[20]

Impact of an

ageing population

Concerns about the impact of an ageing population in

Australia have been expressed in the four intergenerational reports published

by Australian Governments since 2002 (2002, 2007, 2010 and 2015). Much of this

concern is based on projections for a deterioration in the budget position, due

mainly to higher health and aged care expenditure, if policies are left

unchanged.[21]

In terms of retirement incomes policy, one area highlighted

in the intergenerational reports has been the continued heavy reliance on the

age pension for income support in retirement, albeit with a shift of more

recipients to a part-pension as the superannuation system matures.[22]

This theme of a continued dependence on the age pension remains a concern to

some policy makers, with the National Commission of Audit noting in 2014:

Despite the increasing shift towards part-rate pensions the

proportion of older Australians eligible for Age Pension is projected to remain

constant at 80 per cent. There is no projected increase in the proportion of

individuals who are completely self-sufficient despite the significant investment

in superannuation over time. This includes the impact of the recent decision to

increase the Superannuation Guarantee rate to 12 per cent by 2019–20.

The reasons for this are multi-faceted, but are likely to

include people deliberately tailoring their affairs to meet current eligibility

criteria such as by consuming assets or transferring equity to the principal

residence or other assets that are not means tested. Current means testing

arrangements mean that people with significant levels of income or assets can

still be eligible for a part-rate pension.[23]

Fairness

Concerns about the ‘fairness’ of superannuation tax

concessions—based primarily around the share of concessions going to higher

income earners—have been raised over recent years.

Rudd/Gillard

Governments

In 2010, the Report to the Treasurer: Australia’s

Future Tax System: (Henry Tax Review) examined the structure of existing

superannuation tax concessions. The review noted:

The structure of the existing tax concessions is inequitable

because high-income earners benefit much more from the superannuation tax

concessions than low-income earners.

Access to concessions should not depend on an employer’s

remuneration policies, such as whether a person can make salary sacrifice

contributions. The age limit on who can make superannuation contributions also

limits access to concessions.

Taxing superannuation contributions reduces the level of

superannuation guarantee contributions invested in the fund. This limits the

adequacy of the superannuation guarantee in providing for retirement incomes in

a way that is inequitable for low-income earners compared with other saving

alternatives.[24]

While the Gillard Government did not act on the Henry Tax Review’s

recommendations in relation to the taxation of superannuation, it did introduce

a number of changes, including the LISC and lower contributions caps, partly to

address issues related to the equity of superannuation tax concessions.

Introducing the Bill to implement the LISC in late 2011, then Assistant

Treasurer, Bill Shorten, noted:

The Gillard government is acting on the recommendation of the

Henry review, which said that superannuation tax concessions should be

distributed more equitably.

...

This will be one of the most significant wealth creation

reforms targeted at low-income earners in modern Australian history. Put

simply, the government is lowering the tax burden on low-income

Australians—people who go to work every day—and directing this forgone tax

revenue into their superannuation accounts to help them build for the future.[25]

Despite these changes, the equity of superannuation tax

concessions remained an issue for the Gillard Government. In early 2012, the

Treasurer Wayne Swan, and Minister for Financial Services and Superannuation

Bill Shorten, announced the establishment of a ‘superannuation roundtable’,

comprised of industry representatives, selected academics and others, ‘to

consider ideas raised at the Tax Forum for providing Australians with more

options in retirement and improving certain superannuation concessions’.[26]

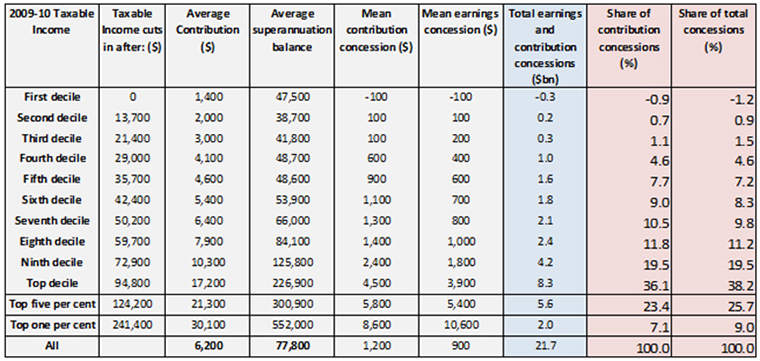

Work undertaken as part of the round table process

provided modelling about the distribution of tax concessions across income

groups, which revealed that in 2009–10, the top five per cent of taxpayers

by taxable income received one-quarter of the value of tax concessions, with

taxpayers with lower incomes receiving a small share of tax concessions (Figure

2).

Figure 2: Estimated distribution of superannuation tax concession 2009–10

Source: The Treasury, Distributional

analysis of superannuation taxation concessions: a paper to the superannuation

roundtable, The Treasury, Canberra, April 2012.

To address these concerns, the Gillard Government

announced changes to superannuation tax arrangements. In the 2012–13 Budget,

the Government announced the introduction of an additional 15 per cent

contributions tax from the 2012–13 financial year for individuals earning above

a $300,000 income threshold.[27]

This measure was legislated by the Tax and

Superannuation Laws Amendment (Increased Concessional Contributions Cap and

Other Measures) Act 2013 and remains in place. In April 2013, the

Gillard Government announced a proposal to cap at $100,000 the tax exemption

for earnings on superannuation assets supporting income streams from 1 July

2014, with a concessional tax rate of 15 per cent applying thereafter.[28]

However, a Bill to put this measure into effect was not introduced into the

Parliament.

Abbott

Government

Following the 2013 election, the Abbott Government

announced in November 2013 that the measure to cap at $100,000 the tax

exemption for earnings on superannuation assets supporting income streams

measure would be dropped.[29]

Momentum to support further changes in superannuation tax

changes was supported in 2014 by the Financial System Inquiry (FSI) (Murray Inquiry).

In the Murray Inquiry’s interim report (July 2014), the relatively high share

of total superannuation tax concessions for higher income earners was examined

and the report noted:

Recent changes to concessional and non-concessional

contribution caps and a higher contributions tax rate for very-high-income

earners (30 per cent above $300,000) have attempted to achieve more equitable

outcomes. Further adjustments to policy settings may be required.[30]

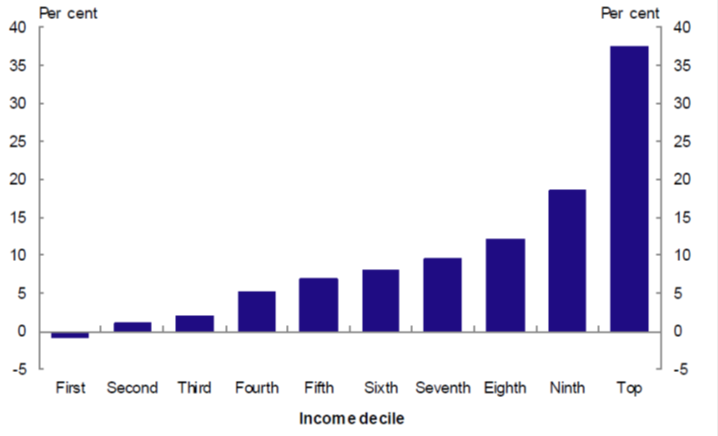

The final report of the Murray Review (released 7 December

2014), presented information on the distribution of total superannuation tax

concessions across income groups, and noted that the majority of tax

concessions accrue to the top 20 per cent of income earners (Figure 3).

While the Murray Review considered two options to better target superannuation

tax concessions—reducing the non-concessional contributions cap and levying

additional earnings tax on superannuation account balances above a certain

limit—the Review did not make specific recommendations and instead considered

that these should be part of the proposed tax review.[31]

The Abbott Government tax review released a discussion

paper on 30 March 2015.[32]

In the discussion paper, the Government noted:

While there are policy grounds for superannuation being taxed

at a lower rate than labour income, there are issues around the distribution of

the impacts and their effectiveness in supporting higher retirement incomes, as

well as their complexity. The Financial System Inquiry made observations

relating to the differential earnings tax rate across the accumulation and

retirement phases, as well as the targeting of superannuation tax concessions.

The Government has indicated these will be considered as part of the Tax White

Paper process.[33]

Figure 3: Share

of total superannuation tax concessions by income decile, 2011–12

Source: Financial System Inquiry,

Financial System Inquiry: final report, The Treasury, Canberra,

November 2014, p. 138.

Following the 2015–16 Budget, which did not include any

superannuation tax measures, the Treasurer Joe Hockey noted:

As everyone in this room would know, there has also been a

lot of talk about superannuation tax concessions. Some believe that the

solution to the nation’s ills is to slug those who are taking responsibility

for their retirement with higher taxes on superannuation.

This government absolutely rejects that view. As we promised

prior to the last election, we will not engage adverse or unexpected changes to

superannuation in our first term of government. Nor do we have plans to

increase superannuation taxes into the future.

...

Stability in tax policy is important, and even more important

where individuals rely on the long term stability of the rules around

retirement savings. What self-funded retirees and part pensioners need now,

more than ever, is stability not more tinkering with the system.[34]

Turnbull

Government

In November 2015, the Turnbull Government signalled that it

was considering changes to superannuation tax concessions. In a speech to the

Association of Superannuation Funds of Australia on 27 November 2015, the

Treasurer Scott Morrison noted:

Retirees have saved for their retirement under the existing

rules across their working lives. The Government acknowledges these efforts and

sacrifices.

And yet we must also balance all that with the goal of

shaping the superannuation system so it provides opportunity to all

Australians. Because until tax concessions and the superannuation system are

perceived to strike the right balance, there’ll continue to be calls for

tinkering and more changes.[35]

Support for changes to superannuation tax concessions was also

continuing to come from other sources, including superannuation industry

groups. For example, in its submission for the 2016–17 Budget in February 2016,

the Association of Superannuation Funds of Australia included several policy

suggestions, such as a $2.5 million balance cap, as well as lifetime

concessional and non-concessional contributions caps as elements of ‘ensuring

equity, adequacy and sustainability in the system’.[36]

Closer to the 2016–17 Budget, John Daley from the Grattan

Institute in March 2016 noted:

The debate about superannuation tax breaks is getting to the

pointy end.

...

Ultimately, where you draw the lines on an “adequate

retirement” and super tax breaks are political questions. But on any view, the

current superannuation tax breaks are much more than needed for an extremely

comfortable retirement.[37]

Key

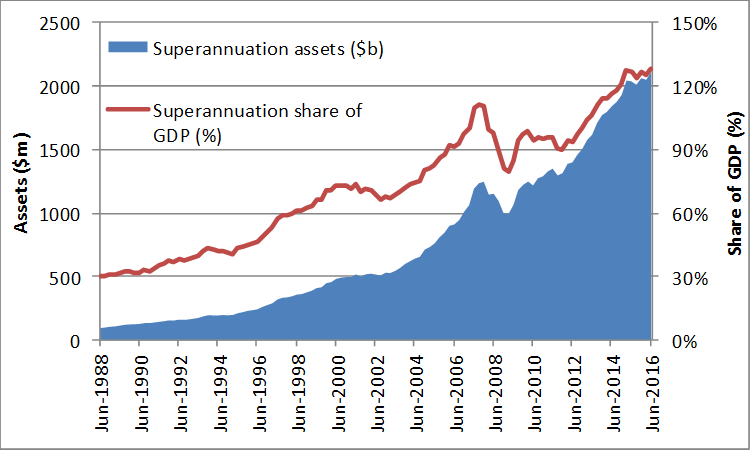

superannuation figures and information

The superannuation system is an important part of the

Australian economy. Accumulated superannuation balances and contributions form

an important part of an individual’s retirement income savings.

Value of

superannuation savings

As at 30 June 2016, the total value of accumulated

superannuation savings in Australia was around $2.1 billion.[38]

There has been significant growth in total superannuation savings both in terms

of the value of savings and as a share of GDP since the late 1980s (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Accumulated

superannuation savings, June 1988 to June 2016

Source: Parliamentary Library estimates based on Treasury methodology using

data from the Australian Prudential Regulation

Authority (Quarterly superannuation performance, various issues) and Australian Bureau of Statistics

(Australian National Accounts: National Income,

Expenditure and Product, various

issues).

The value of superannuation savings is likely to continue

to increase over the medium to long term, with various estimates putting the

value of assets managed by superannuation funds in the order of $6–9 trillion

in the mid‑2030s.[39]

The

importance of superannuation for household savings

Superannuation assets form an important and growing part of

household wealth. The Australian Bureau of Statistics estimates that superannuation

savings account for around one-third of average household assets, with property

assets (including the value of occupied housing) accounting for more than

55 per cent of household assets.[40]

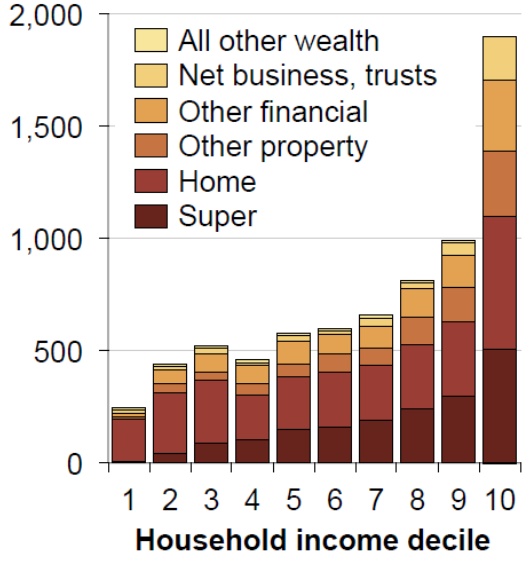

That said, analysis by the Grattan Institute shows that superannuation assets

held by households are largely held by wealthier households, which also tend to

hold significant wealth outside of the home and superannuation (figure 5).

Figure 5:

Household mean wealth by asset class, by household income decile, 2013–14

($’000)

Source: J Daley, B Coates and H Parsonage, How

households save for retirement, Background paper, Grattan Institute, Melbourne,

October 2016, p. 5.

Individual

superannuation savings and contributions

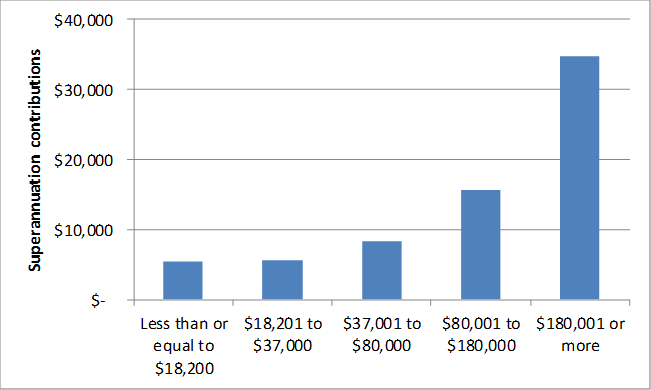

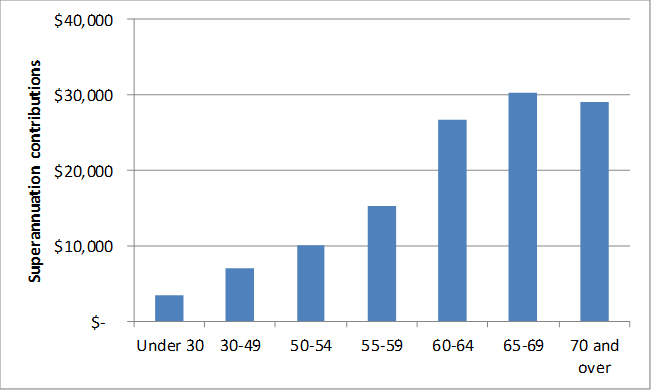

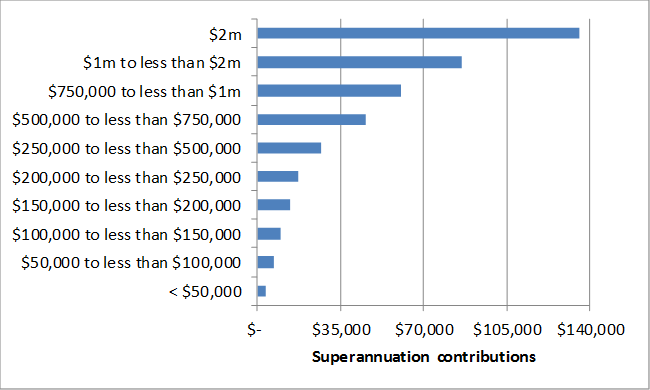

Data published by the Australian Taxation Office provides

information about the value of contributions to superannuation and the broad

characteristics of individuals who had superannuation contributions in 2013–14.

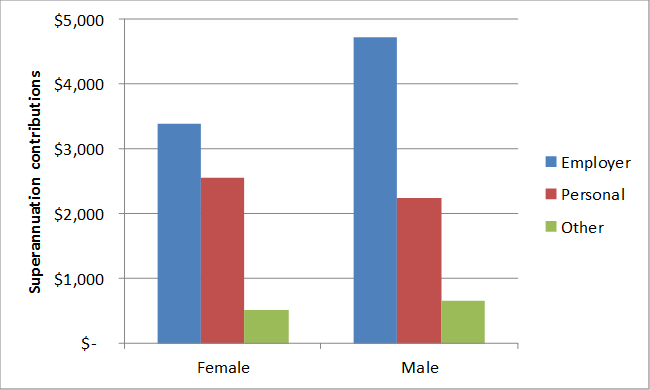

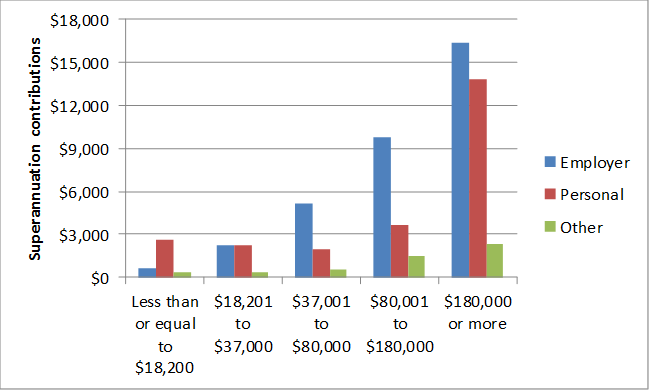

In broad terms, these data show:

- the

average level of contributions generally increases with age, income and the

value of accrued superannuation balances

- women

on average have lower contributions than men, for all contributions types, and

- personal

contributions form an important part of contributions for those aged more than

50 and those on the highest level of income (Figure 6).

Figure 6:

Average superannuation contributions, by taxable income, age, superannuation

balance, gender and type of contributions, 2013–14 ($)

|

By taxable income

|

|

|

By age

|

|

|

By superannuation balance

|

|

|

Type of contributions, by gender

|

|

|

Type of contributions by taxable income

|

|

|

Type of contributions by age |

|

Source: ATO, ‘Individuals’,

Taxation statistics 2013–14, ATO website, last modified 18 March 2016, ‘Table

24, Superannuation fund contributions, for the 2013–14 financial year, by

superannuation total accounts balance, taxable income and age range’, ‘Table

25, Superannuation fund contributions, 2013–14 financial year, by age range,

gender and taxable income’.

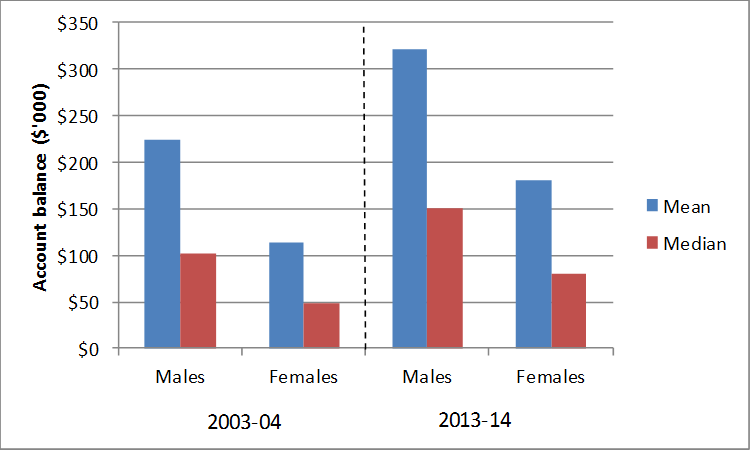

Estimates by the Australian Bureau of Statistics on average superannuation

balances suggest that individuals have been able to accumulate higher

superannuation balances, and that as they near retirement ages, they will

retire with higher balances that a decade ago. That said, average balances for

women remain below those for men (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Mean and median male and female superannuation account balances

for those aged 55–64 years, by gender, 2003–04 and 2013–14 ($’000)

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Household

Income and Wealth, Australia, 2013–14, cat. no. 6523.0, ‘Superannuation

of persons: table 24.3 Superannuation account balances’, ABS, Canberra, 4 September

2015.

Committee

consideration

Senate

Economics Committee

The Bills have been referred to the Senate Economics

Legislation Committee for inquiry and report by 23 November 2016.[41]

Details of the inquiry are at the Committee’s homepage.[42]

The Committee recommended that the Senate pass the Bill.[43]

Labor members of the Committee issued a dissenting report, outlining

alternative positions on two measures and opposing the introduction of catch-up

concessional contributions and changes to tax deductibility for personal

superannuation contributions, which are regarded as ‘unaffordable given the

current fiscal position’.[44]

While not calling for the Bill to be rejected, Labor stated:

Labor Senators will continue to argue for amendments to the

Government’s legislative package, and if unsuccessful on this occasion, will

take the position to the next election.[45]

Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

At the time of writing this Bills Digest, neither of the

Bills had been considered by the Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of

Bills.

Policy

position of non-government parties/independents

Australian

Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party indicated during debate in the

House of Representatives on the Bills that while the ALP would move amendments

to the Bills, it would ‘facilitate’ the passage of the legislation.[46]

The Shadow Treasurer noted:

Let me be very clear: This package is better than it was.

This package is better than nothing. We are glad the government have finally

acknowledged the need for superannuation tax reform. What we will do, in this

debate and in the other place, is make sensible suggestions as to how it can be

improved.

...

If the government refuse, at the end of the day, to accept

those amendments, we will not give the government an excuse to walk away from

this legislation. I will not give this Treasurer an excuse to walk away from

what he has been dragged kicking and screaming to do. We will not let the

perfect be the enemy of the good, and we will facilitate the passage of the

legislation.[47]

2015

announcement

The superannuation policy which the ALP took to the 2016 Federal

election essentially reflected its announcement on 22 April 2015 that it would

limit tax-free earnings on assets supporting income streams to $75,000, after

which a 15 per cent rate would apply and reduce the income threshold at

which the 30 per cent tax rate on concessional contributions applied from

$300,000 to $250,000.[48]

Announcing the policy, the Leader of the Opposition Bill

Shorten and Shadow Treasurer Chris Bowen noted:

A fair and sustainable superannuation system will protect

living standards in retirement and take pressure off the age pension. The

recent Financial System Inquiry found that 10 per cent of Australians currently

receive 38 per cent of all superannuation tax concessions. In particular, the

tax-free status of all superannuation earnings, introduced by the Howard

Government in 2006, disproportionately benefits high income earners and is

unsustainable.

...

We believe these changes are all that are needed to ensure

sustainability at the very top end of our superannuation system. If we are

elected these are the final and the only changes Labor will make to the tax

treatment of superannuation.[49]

Subsequent

August announcement

On 24 August 2016, the ALP announced its position in

relation to the 2016–17 Budget package of measures, noting that that it would

amend the proposal to reduce the income level at which the 30 per cent tax on

contributions applied to $200,000 rather than $250,000 and that it would:

- oppose

allowing catch-up concessional superannuation contributions

- oppose

harmonising contribution rules for those aged 65 to 74, and

- oppose

allowing tax deductions for personal superannuation contributions.[50]

The Shadow Treasurer Chris Bowen and Shadow Minister for Small

Business and Financial Services Katy Gallagher noted:

Since Budget night, Labor has expressed our concern about the

retrospectivity of the Government’s $500,000 lifetime non-concessional

contribution cap. We committed to consult and make changes to it – something

Scott Morrison should have done ahead of the Budget.

At the same time, we committed to delivering at least the

same quantum of Budget improvements as contained in the Government’s overall

superannuation package.

...

Labor’s measured approach to super reform achieves two

important objectives: ensuring that our tax concessions are fit for the task of

helping Australians save for a dignified retirement, and improving the Budget

bottom line.

Our proposed package is fair, affordable and can be delivered

in the Parliament. Malcolm Turnbull simply cannot say the same about his own

superannuation plans.[51]

Subsequent

November announcement

On 8 November 2016, the ALP announced that it would propose

several changes to the Government’s amended package of measures.[52]

The changes included restating some elements of its 24 August 2016 announcement

which remained as part of the Government’s 15 September 2016 amended

package:

- lowering

the annual non-concessional contributions cap to $75,000

- lowering

the High Income Superannuation Contribution threshold to $200,000, and

- not

allowing for catch-up concessional contributions and tax deductibility for

personal superannuation contributions.[53]

In announcing this position, the Shadow Treasurer Chris

Bowen noted:

Labor will finalise its position on the Government’s

legislation when it is eventually presented to the Parliament. But we urge the

Government to accept Labor’s responsible proposals, and work with us to deliver

superannuation reforms which are fairer and better.[54]

Other

parties and independents

Australian

Greens

The 2016 election superannuation policy of the Australian

Greens (the Greens) was to implement a progressive contributions tax

arrangement for concessional contributions, so that contributions would be

taxed at an individual’s marginal tax rate, less 15 per cent.[55]

Under the proposal, there would also be a government co‑contribution of

15 cents for each dollar of superannuation contributions for those earning

an annual income of under $18,200.[56]

The basis for these proposals is largely related to a view that the existing

tax concessions favoured higher income earners, with the Greens noting:

Superannuation tax breaks for the very wealthy are placing an

unfair and unsustainable burden on the Budget. It is time to end the unfair tax

breaks in our super system, support low income earners and raise the revenue we

need to fund schools, hospitals and infrastructure.[57]

Liberal

Democrats

Liberal Democratic Party’s 2016 election policies included

a proposal to expand the current superannuation savings account system to

encompass health, unemployment and disability as well as retirement—and to also

make such accounts tax free with respect to contributions, earnings and

permitted withdrawals.[58]

Following the 27 September 2016 announcement about

changes to the package of measures, Senator Leyonhjelm was critical of the

measures, stating:

The underlying problem is that, while a superannuation

balance of $1.6 million might sound like a lot, it is not enough to retire on

without the age pension. With low interest rates and the increased possibility

of living for at least 30 years in retirement, $1.6 million might only buy an

annuity starting around $50,000, rising with inflation.

...

Unless interest rates increase substantially or we start

dying earlier, a much higher super balance will be needed to ensure permanent

ineligibility for the age pension. If there is no benefit in accumulating a

super balance in excess of $1.6 million, there will be no incentive to become independent

of the age pension.

That means the self-funded retiree will become a distant

memory while the working age population will bear a crushing tax burden to pay

for pensions.[59]

One Nation

Pauline Hanson’s One Nation party did not have a specific

2016 election policy relating to superannuation tax arrangements. However, the

party did propose to allow Australians up to the age of 38 to access their

accumulated superannuation funds to use as a deposit to buy their first home.[60]

Nick

Xenophon Team

The 2016 election superannuation policy of the Nick Xenophon

Team (NXT) included proposals to bring forward the increase in the

superannuation guarantee to 12 per cent, improve transparency and end fee

‘gouging’ and a requirement for funds to hold annual general meetings.[61]

In relation to tax arrangements, the NXT proposal was that ‘[t]ax-breaks for

superannuation must be re-calibrated so the greatest benefit is directed to

those with the least savings, and a reduced benefit is enjoyed by those with

very high superannuation savings’.[62]

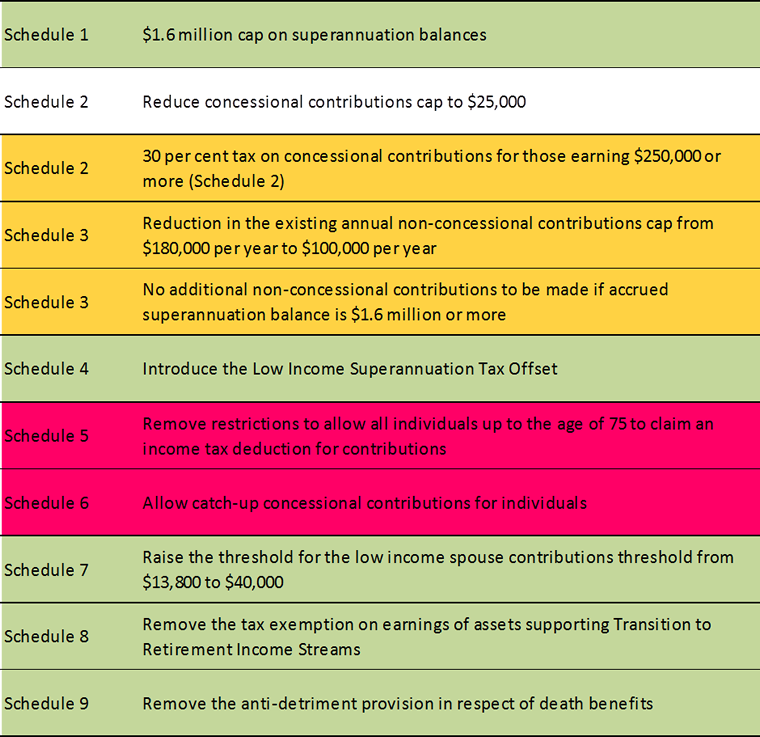

Which

elements of the package have bipartisan support?

Based on the statements made by the ALP on elements of the

package of measures included in the Bill, only two of the measures are opposed

by the ALP. Of the remaining measures, the ALP supports five measures, has

proposed amendments to three measures and has not expressed a view on one of

the measures (Figure 8). That said, as noted earlier, the ALP has indicated

that they will ‘facilitate’ the passage of the Bills through the Parliament.[63]

Figure 7:

Comparison of Government and ALP positions on measures included in the Bill

Notes: Green indicates the measure has bipartisan support.

Orange indicates the ALP has proposed amendments to the measure. Red indicates

the ALP opposes the measure. No colour indicates that the ALP has not expressed

a specific view.

Source: Parliamentary Library analysis of Government and ALP policy statements.

Position of

major interest groups

Superannuation

industry groups

The Association of Superannuation Funds of Australia

(ASFA) had mixed views on the measures announced in the 2016–17 Budget,

supporting the introduction of the LISTO but opposing the reduction in

concessional caps to $25,000.[64]

ASFA also noted:

ASFA has long advocated for support for low income earners

contributing to superannuation. The LISTO scheme provides this and makes the

superannuation system stronger.

While ASFA has previously supported a $2.5 million cap on

balances that can be transferred to the tax free retirement phase, the Budget

proposal for a cap of $1.6 million goes much further. A $2.5 million cap will

have an impact on over 50,000 people, and involve additional revenue of under

$500 million a year—while a $1.6 million cap will affect more than 100,000

people and result in additional revenue for the government of $1.15 billion by

2019/20. ASFA will need to do work to understand the impact on retirement

incomes.

...

The changes to the flexibility caps will allow women, in

particular, who currently retire with less than half the superannuation of men,

to catch up. However, the restriction of a five year period for the calculation

of previously unused cap amounts restricts the effectiveness of this.[65]

Following the Government’s 15 September 2016 announcement

of changes to some of the measures, ASFA was supportive of the changes and

‘urges the Parliament to pass the changes as soon as practical, in order to

provide certainty for people saving for their retirement’.[66]

The interim CEO of ASFA noted:

ASFA has long advocated for both a lifetime cap on

non-concessional contributions and a limit on the total amount tax free in

retirement. The revised superannuation proposals address both issues.

The primary role of superannuation is to provide income in

retirement and it should not be used as an estate planning tool.

The ceiling of $1.6 million, once it is legislated, balances

the need to ensure enough income for a comfortable retirement with ensuring the

level of tax concessions is sustainable in the future.

This is the responsible thing to do for the superannuation

system and for Australia’s long term, fiscal sustainability.[67]

After the introduction of the Bills on 9 November

2016, ASFA noted that it had ‘broadly supported the thrust of the government’s

tax package from its announcement because it makes the superannuation system

more sustainable and fair’.[68]

AFSA considered that the Bills ‘should be passed without any undue delay, to

provide certainty and confidence in the system’.[69]

The Financial Services Council (FSC) considered the

2016–17 Budget announcements had both ‘positive’ and ‘restrictive’ elements.[70]

The CEO of the FSC noted:

The test for this budget is whether Australia will have more

pensioners or more self funded retirees.

...

The new caps and thresholds limit the capacity for

Australians to save for their own retirement and will restrict retirees to an

income of around $80 000 per annum from their superannuation. An $80 000 limit

will fail to cover the costs of retirement for many Australians, when you

include healthcare, aged care and a comfortable standard of living.[71]

Following the Government’s 15 September 2016 announcement

of changes to some of the measures, the FSC welcomed the changes to the

non-concessional contribution caps.[72]

The FSC noted:

For those Australians who can afford it, they will now be

able to place $125,000 into super each year until they reach the $1.6 million

cap. This is made up of $25,000 of concessional contributions and $100,000 of

after tax contributions.

The FSC has consistently argued that the proposed backdating

measures would have been difficult to implement and they also conflicted with

the long-term nature of superannuation policy, undermining opportunities for

consumers to prospectively plan for their retirement.

The removal of the $500,000 cap gives Australians who can

afford to save more, increased flexibility to do so and avoids administration

that would have increased costs for superannuation savers.[73]

After the introduction of the Bills on 8 November

2016, the FSC indicated that it was broadly supportive of the measures

announced in the 2016–17 Budget and had ‘welcomed the Government’s consultation

with industry to work through implementation issues to minimise costs to funds

and consumers’.[74]

The CEO of the FSC noted:

Australians want certainty and confidence in superannuation.

They want to be free to choose their own super fund and they want employers to

be able to offer them a choice of funds. More than anything they want political

parties to draw a line in the sand under changes to the tax treatment of super

so they can plan confidently for their financial futures.[75]

The SMSF Association was supportive of the

introduction of the LISTO following the 2016–17 Budget announcement but noted

several measures of ‘concern’ including the lower $25,000 concessional

contribution cap, the $500,000 lifetime non concessional cap, limiting

tax-free earnings to a balance of $1.6 million and lowering the income

threshold to $250,000 for the higher tax on concessional contributions.[76]

The SMSF Association noted:

The Federal Government’s decision to reduce the concessional

contribution cap down to $25,000 is a backward step that will severely reduce

the ability of people to save adequately for retirement.

... this decision, when coupled with other flawed measures in

the Budget, will send shock waves through an SMSF [Self Managed Super Fund] sector

that was hoping the broad parameters of the system had been settled.

... We strongly believe that adequate concessional contribution

caps are vital to allow people to save for a secure and dignified retirement.[77]

Following the introduction of the suite of Bills on

8 November 2016, the SMSF Association considered that SMSF trustees and

their advisers could have greater certainty in beginning to adjust their

superannuation strategies in advance of the proposed 1 July 2017 start date for

most of the proposed changes.[78]

The CEO of the SMSF Association noted:

The changes allowing the carry forward of unused concessional

contribution cap space and allowing all taxpayers to make deductible

contributions to their superannuation are undoubtedly positives for the system.

These changes greatly increase the flexibility for people[‘s] contribution to

super, especially for women who may have had broken work patterns, allowing

greater opportunities to save for retirement.[79]

Immediately following the 2016–17 Budget announcement, Industry

Super Australia (ISA) generally supported the package of measures, which

they considered had ‘rightly wound back’ the ‘overly generous’ superannuation

tax concessions.[80]

The ISA in particular welcomed the decision to introduce the LISTO, noting:

This top up payment, which was due to be abolished in 2017,

is critical in ensuring lower paid workers don’t end up paying more tax on

their super than they do on their take home pay.

... This is a sensible step in the right direction for which

Industry SuperFunds have strenuously advocated. However, with a whopping 45%

gap in super savings between men and women, more will need to be done to

actively boost the super savings of this lower paid group to help them reach a

comfortable retirement standard.[81]

Following the Government’s 15 September 2016

announcement of changes to some of the measures, the ISA expressed its support

for the changes, noting:

We would hope all MPs will now give careful consideration to

these changes so the reforms can start to make their way through the

Parliament. These are evolutionary, not revolutionary changes.[82]

The Australian Institute of Superannuation Trustees

(AIST) responded positively to the 2016–17 Budget announcements, seeing the

measures as a ‘necessary step toward a fairer and more sustainable super system.[83]

Responding to the changes announced by the Government on 15 September

2016, the AIST remained supportive of the overall package, noting:

While AIST is disappointed to see the reversal of rules

affecting older workers aged 65 to 74, on balance these changes are in keeping

with the need to improve the fairness and sustainability of the system ... Furthermore

these changes are considerably easier for funds to implement and do not add to

the complexity of the system.[84]

On the introduction of the suite of Bills into the

Parliament, the AIST ‘urged all Federal Parliamentarians to support tax changes

to superannuation that improve retirement outcomes for low income earners,

including women’.[85]

Professional

bodies

Following the 2016–17 Budget announcements, the Actuaries

Institute welcomed the proposed changes, which in its view would ‘inject

more equity and fairness into the retirement incomes system’.[86]

The Institute noted:

Overall the Budget changes improve the system, making it

fairer while also increasing revenue to assist the economy in these financially

constrained times.

...

The Institute believes these changes will help to meet the

Government’s objective of superannuation, which was adopted from the Financial

System Inquiry – to provide income in retirement to substitute or supplement

the Age Pension.[87]

The Actuaries Institute welcomed the Government’s

15 September 2016 changes, noting:

The proposed changes meet the overall targets for the

superannuation and retirement incomes system of adequacy, equity and

sustainability. Today’s announcement represents a reasonable compromise in

order to allow the package of much needed superannuation tax reforms to

proceed.[88]

The Tax Institute was supportive of the changes

announced in the 2016–17 Budget.[89]

The President of the Institute noted:

The Budget delivered today is a good step in the evolution of

our tax system.

...

The superannuation measures better target tax concessions in

the superannuation system to make the system more equitable without

compromising stability.[90]

Following the 2016–17 Budget announcement, the Chartered

Accountants Australia New Zealand (CAANZ) expressed concerns that the ‘confidence

in the super system has been severely shaken by some of the changes announced

in the Turnbull Government’s budget’.[91]

The CAANZ was supportive of the proposal for a lifetime non-concessional

contributions cap but believed that $500,000 was too low, and that a

higher lifetime limit should apply for those aged at least 50 years of

age.[92]

The CAANZ also considered that the proposed annual concessional cap of

$25,000 was too low.[93]

Thinktanks/research

groups

In a September 2016 paper entitled A

Better Super System: Assessing the 2016 Tax Reforms, the Grattan

Institute considered the different policies presented by the Government in

the 2016–17 Budget and those proposed by the ALP.[94]

The Grattan Institute concluded that the policies were not that different,

noting:

The major parties disagree about relatively little in this

reform debate. The ALP would not count post-tax contributions between 2007 and

the present. On the other hand it would adopt a number of other policies that

would contribute even more to budget repair. Any combination of the packages on

offer would improve the current system overall.

...

The proposed changes to super tax are built on principle,

supported by the electorate, and largely supported by all three main political

parties. If common ground cannot be found in this situation, then our system of

government is irredeemably flawed.

Even after the reforms, super tax breaks will still mostly

flow to high income earners who do not need them. The budgetary costs of super

tax breaks will remain unsustainable in the long term. Further changes to super

tax breaks will be needed in future.[95]

The Institute of Public Affairs (IPA) did not support

the 2016–17 Budget changes, making reference to the Coalition’s 2013 election

superannuation policy and a ‘disdain for anyone who has worked hard, made

sacrifices, and become successful’.[96]

The IPA noted:

The language the government uses to justify its changes

basically implies that anyone with more than $1.6 million in superannuation is

somehow engaged in a rort or a tax dodge. But what the Coalition doesn't

acknowledge is that up until a fortnight ago it was deliberately encouraging to

do exactly what people are now being blamed for. In any case, anyone with $1.6

million in superannuation has most likely spent the majority of their working

life paying nearly half of their income to the government in taxes.

Some of those most worried by what the government has done

are not affected by these changes to superannuation. Those not immediately

targeted by the government in this budget don't know what's going to happen

next. Now that the Coalition has opened the door to blatant and retrospective

changes to superannuation, there's the potential for a future Labor/Greens

government to do what the Coalition is attempting - but only worse.[97]

The Centre for Independent Studies (CIS) was critical

of some aspects of the 2016–17 Budget announcements, considering that the

changes ‘do not address the core problem of pension dependence’.[98]

Robert Carling from the CIS, in a September 2016 article entitled How

should super be taxed?, was critical of efforts to improve the

‘fairness’ of tax concessions, noting:

Fairness is a subjective concept, but what can be said

objectively is that the overall tax/transfer system is highly redistributive

without any further reshaping of superannuation taxes to mirror the progressive

personal income tax. Moreover, there are significant simplification benefits in

flat superannuation taxes. The recent and proposed changes are introducing new

complexities to the system.

Balancing the budget is an important objective but in itself

does not override the principle of concessionality for superannuation. Revenue

constraints will always require limits on access to concessionality, but the

tightening of access proposed by the government is draconian and little

justification has been provided for the details. The government needs to go

back to the drawing board, review its proposals, and produce a green paper for

consultation, including the actuarial basis for revised proposals.[99]

Other

groups

National Seniors Australia (NSA) was supportive of

the 2016–17 Budget changes, but did express some ‘reservations’ about the

reduction in the concessional contribution cap from $35,000 to $25,000.[100]

The CEO of the NSA noted:

The Turnbull Government has taken a measured but fairly

comprehensive approach to superannuation reform ... The mix, in terms of fairness

and sustainability, appears pretty good.

Currently, women are retiring with half the super balances of

men. Initiatives such as allowing the rollover of concessional caps and

widening access to partner contributions may help address this.[101]

Following the 2016–17 Budget announcements, the Council

on the Ageing Australia (COTA) welcomed the changes, which it considered

were ‘the most significant structural reforms since superannuation was introduced’.[102]

The CEO of COTA noted:

COTA is pleased to see the government move in a direction

that ensures superannuation is used for the purpose it was originally intended

- as a way for people to save for their retirement rather than a wealth

accumulation scheme for Australia's highest earners.

...

The changes, many of which COTA has called for over the last

few years, will make superannuation much more sustainable and fit for purpose

for the long term.

...

Overall this is a significant and integrated set of reforms

that better utilises taxpayer funded concessions for genuine retirement income

support.[103]

The Australian Council of Social Services (ACOSS)

welcomed the 2016–17 Budget superannuation measures, considering they would ‘take

us in the right direction, tackling unfair concessions for people on higher

incomes, and providing assistance to people who struggle to secure adequate

retirement savings’ but also that ‘the tax treatment of super remains biased

towards higher income earners, and the door for future reform must remain open’.[104]

Responding to the Government’s 15 September 2016

announced changes to the package of measures, ACOSS welcomed the reduction in

the non-concessional cap to $100,000, but criticised the continuation of the

three-year bring forward rule and the retention of the carry-forward measure of

unused concessional contributions.[105]

Financial

implications

The Explanatory Memorandum notes that the measures to be

implemented by the Bills are estimated to increase the underlying cash balance

by $2.8 billion over the four years to 2019–20 (Table 1).[106]

Table 1: Financial

impact of measures included in the Bills, underlying cash basis, 2016–17 to

2019–20 ($ million)

| Measure |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

Total |

| $1.6 million transfer balance cap |

-4.4 |

500.0 |

650.0 |

700.0 |

1,845.6 |

Concessional superannuation contributions

and lowering

threshold for high income

earners additional contributions tax |

-2.8 |

499.1 |

797.8 |

1,048.9 |

2,343.0 |

| Annual non-concessional contributions |

.. |

.. |

50.0 |

150.0 |

200.0 |

| Low income superannuation tax offset |

- |

-2.8 |

-651.1 |

-801.1 |

-1,455.0 |

| Deducting personal contributions |

- |

350.0 |

-500.0 |

-700.0 |

-850.0 |

| Unused concessional cap carry forward |

- |

- |

- |

-100.0 |

-100.0 |

| Tax offsets for spouse contributions |

- |

- |

-5.0 |

-5.0 |

-10.0 |

| Innovative income streams and integrity |

.. |

130.0 |

160.0 |

180.0 |

470.0 |

| Anti-detriment provisions |

- |

- |

105.0 |

245.0 |

350.0 |

| Administration and consequential amendments |

- |

* |

* |

* |

* |

| Total |

-7.2 |

1,476.3 |

606.7 |

717.8 |

2,793.6 |

*These changes are assessed as having an unquantifiable but small

impact.

Source: Explanatory

Memorandum, Superannuation (Objective) Bill 2016 [and] Treasury Laws

Amendment (Fair and Sustainable Superannuation) Bill 2016 [and] Superannuation

(Excess Transfer Balance Tax) Imposition Bill 2016, pp. 9–10.

As noted previously, the package of measures included in

the Bills is different in several ways to that announced in the 2016–17 Budget:

- the

measure allowing for the carry forward of unused concessional contributions cap

amounts commences one year later, from July 2019, rather than from July 2018

- a

measure to provide for a lifetime non-concessional contributions cap of

$500,000, backdated to 1 July 2017, is no longer part of the overall

package—this has been replaced with the measure for lower annual

non-concessional cap of $100,000, for those with a superannuation balance of

$1.6 million or less

- a

measure to harmonise contribution rules for those aged 65 to 74 has been

dropped.

With the financial impact of the 2016–17 Budget measures

presented in the budget papers on an accrual basis, and those in the

Explanatory Memorandum presented on a cash basis, it is difficult to directly

compare the financial impact between the 2016–17 Budget package of measures and

those included in the Bills.

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed

the Bills’ compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or

declared in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The

Government considers that the Bills are compatible.[107]

Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights

In its report on 22 November 2016, the Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Human Rights noted that the Bills did not raise human rights

concerns.[108]

Key issues

and provisions

This section provides an overview of each Schedule to the

main Bill and highlights some issues that may be of interest in debate about

the Bills.

How many

people are affected by the proposed changes?

When the measures were announced at the 2016–17 Budget the

Government emphasised that a relatively small number of people that would be

negatively affected by some of the proposals. In his Budget speech, the

Treasurer noted that the implementation of the transfer balance cap, lifetime

non-concessional cap and the 30 per cent contributions tax for those on high

incomes will each affect less than one per cent of superannuation fund members

and the reduction in the concessional contributions cap to $25,000 would affect

three per cent of fund members.[109]

Information prepared at the time of the Budget and later to the Senate

Economics Legislation Committee also gave estimates of how many people would be

impacted by the 2016–17 Budget proposals.[110]

In addition to information provided by the Government, the

Association of Superannuation Funds of Australia and the Grattan Institute have

also provided estimates for the number of people affected by some measures. In

some cases, the Government provided two estimates for the same measure (Table

2).

Table 2:

Estimates of the number of people affected by the 2016–17 Budget superannuation

measures as amended in September 2016

| Measure |

Government |

Association of Superannuation Funds of Australia |

Grattan Institute |

| $1.6 million transfer balance cap |

Less than 160,000 (a) |

110,000 |

60,000 |

| $25,000 concessional contributions cap and lowering

threshold to $250,000 for high income earners additional 15% contributions

tax |

Around 560,000 (a)

Less than 1 per cent fund members (additional contributions

tax) |

Up to 500,000 (many

of these affected by both) |

550,000 |

| $100,000 cap on non-concessional contributions |

Less than 160,000 (a) |

|

|

| Low income superannuation tax offset |

3.3 million (2/3 of whom are women) and

3.1 million |

3,200,000 |

|

| Deducting personal contributions |

800,000 and 850,000 |

850,000 |

|

| Unused concessional cap carry forward |

220,000 and 230,000 |

230,000 |

|

| Tax offsets for spouse contributions |

5,000 |

5,000 |

|

| Remove tax exempt status of income from assets supporting

transition to retirement [TTR] income streams |

110,000 |

550,000 plus (b) |

115,000 |

| Anti-detriment provisions |

|

20,000 (annual) |

20,000 |

Notes: (a) Estimated by the Parliamentary Library based on

numbers cited by the Government and a total number of superannuation account

holders of 16 million (b) ASFA noted some individuals may have more than

one TTR account, and some TTR account holders might be able to satisfy a

condition of release for a normal superannuation account based income stream.

Source: S Morrison, ‘Second

reading: Appropriation Bill (No. 1) 2016–2017’, House of Representatives, Debates,

3 May 2016, p. 4255; The Treasury, Making

a fairer and more sustainable superannuation system, Budget 2016: superannuation

fact sheets, The Treasury, Canberra, May 2016; Senate Economics Legislation

Committee, Official

committee Hansard, (proof), 19 October 2016, p. 101; The Treasury,

‘Superannuation

reforms’, The Treasury website; Association of Superannuation Funds of

Australia, Individuals

affected by superannuation budget measures, media release, 2 June

2016; J Daley, B Coates and W Young, A

better super system: assessing the 2016 tax reforms, Working paper, 1,

2016, Grattan Institute, Carlton, September 2016.

Schedule

1—Transfer balance cap

Commencement

The amendments in Schedule 1 to the main Bill commence on

the first 1 January, 1 April, 1 July or 1 October to occur after Royal Assent.

Key

provisions

Schedule 1 of the main Bill amends various tax and

superannuation laws to implement a system to limit the amount of capital

individuals can transfer to the retirement phase to support superannuation

income streams. This in turn, limits the amount of superannuation fund earnings

that are exempt from taxation.[111]

Under this system tax-free investment earnings on superannuation will be limited

to earnings in a ‘transfer balance account’ which is capped at $1.6 million.

The measure is to take effect from 1 July 2017.

Is a

$1.6 million cap too high, too low, or about right?

Item 4 of the Schedule 1 to the main Bill inserts proposed

Division 294 —Transfer balance cap into the ITAA 1997. It operates

to:

- place

a cap on the total amount a person can transfer into the retirement phase of

their superannuation

- where

the balance of the account exceeds the cap, an individual will be required to

remove the excess from the retirement phase and to pay excess transfer balance

tax.[112]

Within the new Division, proposed section 294–35 specifies

that the transfer balance cap for 2017–18 is $1.6 million. The

$1.6 million transfer balance cap will be subject to indexation

arrangements in proposed section 960–285,[113]

which indexes the $1.6 million amount for 2017–18 (in

$100,000 increments) to changes in the all groups consumer price index

from the quarter ending 31 December 2016, as measured by the Australian

Bureau of Statistics.[114]

In his second reading speech, the Treasurer, Scott Morrison

noted that an amount of $1.6 million was ‘around twice the level at which

access to the Age Pension ceases on account of an individual’s assets’.[115]