Papers on Parliament No. 47

July 2007

Prev | Contents | Next

I want to talk to you today about one of the classic—if not the classic—second chambers of the world, and the changes that it has recently undergone. My biggest current research project (and obviously not the one that brings me to Australia) is looking at the change the British government made to the House of Lords in 1999, and the effect that has had on the operation of the British parliament and on British politics in general.[1] My contention, which is becoming less contentious all the time as other people conclude the same, is that an allegedly small reform has had very significant effects, and may even come to be looked back on as a turning point in British politics. This tells us something interesting not only about Britain, but also about parliaments, bicameralism and parliamentary reform in general.

I will structure what I’m going to say to you in five parts:

- First, I’ll give you a bit of background about the House of Lords: who sat there before reform, what the reform did, and who sits there now.

- Second, I’ll suggest some reasons why the chamber might have greater confidence as a result of its reform.

- Third, I’ll provide some evidence that it does indeed have greater confidence, and that this is translating into greater de facto power.

- Next I’ll quickly mention what implications these developments have for the prospects of future reform in the UK.

- But what I really want to concentrate on is the bigger conclusions: what the developments tell us about parliamentary reform, about the changing shape of British politics and about bicameralism in general.

Background

The House of Lords, as I’m sure most of you know, has always been, and still remains, an unelected institution. It is one of the oldest parliamentary chambers in existence, having developed from the council which was called together to advise the monarch as early as the thirteenth century, and save for a brief period of abolition between 1649 and 1660 following the English civil war, it has been continuously in existence, and its composition and powers have evolved in gradual steps.

Since its foundation at the start of the twentieth century the Labour Party had been committed to Lords reform. The chamber was seen as one of privilege and unaccountable power, comprising as it did mostly of hereditary peers—members of the nobility who had inherited their titles from their fathers. However, reform in the twentieth century was piecemeal and often frustrated. In 1911 the left wing Liberal government reformed the Lords’ powers—removing the chamber’s veto and reducing this to a power of delay. But a promised further reform to create ‘a Second Chamber constituted on a popular instead of hereditary basis’ was never brought into effect.[2] In 1949 the post-war Labour government reduced the chamber’s delaying power further from roughly two years to one, but did nothing about its composition. In 1958 a Conservative government introduced life peerages, allowing members to be appointed for life without passing the titles to their offspring. This reform—which also brought women into the chamber for the first time—was influential, and most new members appointed after this date were appointed as life peers.

When Labour came to power in 1997 the House of Lords included 759 hereditary peers and 477 life peers. In addition 26 Bishops and Archbishops of the Church of England sit in the House, and a number of senior judges who are appointed to form the UK’s highest court of appeal (I don’t intend to dwell on these last two types of members as their numbers are small and the position of the so-called ‘Law Lords’ is about to change due to the creation of a new Supreme Court). Labour remained committed to reform of the Lords, as well as to a raft of other constitutional legislation, including devolution in Scotland and Wales and a Human Rights Act. Its election manifesto promised that it would remove the hereditary peers as a first step to creating a ‘more democratic and representative’ second chamber. A bill was published in 1999 to implement the first stage of reform, and a Royal Commission was established to consider the options for the second stage.

The bill passed, without as much difficulty as many had expected, later in 1999. One reason for its ease of passage was that a compromise had been struck, whereby 92 hereditary peers (10 per cent of the total plus some office holders) would remain until the next stage of reform.[3] The Conservative Party in particular claimed that Labour had no intention of moving to the second stage and that it simply sought political advantage through reform. Of the hereditary peers that took a whip, 301 were Conservatives and only 19 were Labour. Many others were independents, but suspected by Labour of Conservative leanings.[4] The political imbalance amongst the hereditary peers was always quite openly and understandably a motivation for Labour to reform the House. By retaining 92 of these members the Conservatives hoped perhaps to embarrass Labour into a next stage of reform, but also to retain some of their own most active members.

So when parliament resumed in November 1999, 655 hereditary peers had been expelled. As a result the House of Lords was much smaller, and much more politically balanced, than it had been before. Of the 666 members who remained, the great majority were life peers, plus the 92 hereditaries and small number of Law Lords and Bishops. The House was still wholly unelected, and could certainly be considered only partially reformed. Indeed most debate about the Lords in Britain since then has focussed on its continued unreformed state. Labour remains in power but (as the Conservatives predicted) no further reform has been forthcoming. Many are therefore still waiting for the ‘more democratic and representative’ chamber that was promised in 1997.

I first started writing about the Lords in order to inform debates about reform, but as more and more time has passed and this still hasn’t materialised, I have grown increasingly interested instead in the effects of the reform that’s already happened. As I said, the chamber appears more confident and assertive, and as a result seems to be gaining strength. I’ll first say why this might be the case, and second what the evidence is.

Reasons for greater confidence

I suggest that there are four reasons why the House of Lords, for all its strangeness, may feel—and indeed may be justified to feel—more confident than previously to intervene in policy debates and to challenge the executive.

The first and most obvious is that heredity is no longer the main route into the chamber. This was a clearly anachronistic practice in a modern democracy, and did little to gain the House of Lords respect. Although a number of hereditary peers remain, they are a small fraction of the previous total, and furthermore were chosen (in elections by their peers) largely on their record in the House. Most are active parliamentarians and many are individually well-respected. In any case, whatever your views on these members, they’re now a small minority, and all of the others in the house were chosen on their merits.

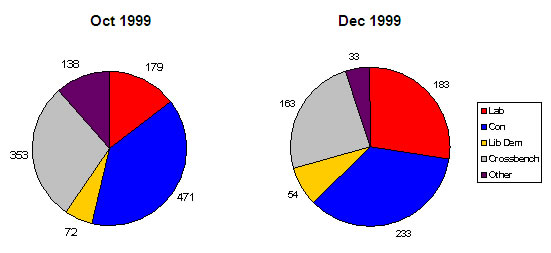

Figure 1: Party balance in House of Lords before and after reform

Second, and at least as important, the party balance in the chamber has fundamentally changed. While previously it was permanently dominated by the Conservatives, it is now a chamber of no overall party control. In the past Conservative governments were almost assured of getting their legislation, since in extremis they could call in their so-called ‘backwoodsmen’—those Conservative hereditaries who normally never appeared. When Labour was in government, in contrast, they had to rely on the restraint of the Conservatives not to defeat their legislation. Peers therefore learned to act with great caution and not use most of the power they had. In particular conventions grew up that government manifesto measures should not be blocked.

Figure 1 shows the big difference in the chamber’s balance immediately before and after reform. Now the two main parties are fairly equally matched in terms of numbers, both holding around 200 seats, with the balance of power held by the third party—the Liberal Democrats—and a large group of independent ‘Crossbenchers’. This situation broadly remains, although in 2005 the Labour Party went on to become marginally the largest party in the chamber for the first time.

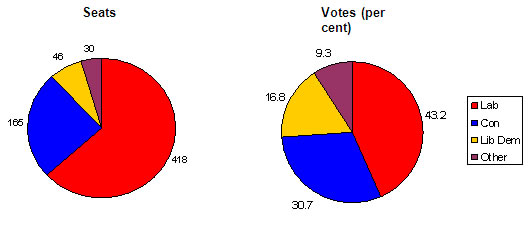

The new House of Lords is clearly more representative than its predecessor. But in terms of party balance it can also be argued to be more representative than the House of Commons. Our single member constituency system for the lower house, like yours, tends to produce inflated majorities for the governing party and under-represent minor parties in particular. In the 1997 and 2001 parliaments the situation was quite extreme. At the 1997 election Labour won 63 per cent of seats on 43 per cent of the vote. These figures are shown in Figure 2. Comparing vote shares with seats in the two chambers, the Lords appears to be more reflective of public opinion at the election even at a glance—with the large number of independent members perhaps matching the 30 per cent of people who didn’t vote at all. Applying the measures political scientists use to gauge proportionality confirms that the distribution of seats in the Lords is far more proportionate than that in the Commons.

Figure 2: Party balance in House of Commons seats and votes, 1997

In part for these reasons, the Lords seems to enjoy greater public support than previously, and elite attitudes to the chamber have also changed, particularly on the Labour side. During the reform debates, Labour’s leader in the House of Lords stated that removal of the hereditary peers would make the chamber ‘more legitimate’.[5] A survey we conducted amongst MPs in 2004 found that 75per cent of Labour MPs and 54 per cent of Liberal Democrats believed that the chamber was more legitimate as a result of its reform.[6] Furthermore a majority of MPs—including a majority of Labour MPs—believed that the Lords was justified in blocking unpopular government policies. These views were echoed in surveys we conducted of public opinion. These found that two-thirds of voters believed the Lords was justified in blocking an unpopular bill—even if it had appeared in the government’s manifesto.[7]

The final reason that the Lords may feel more justified in flexing its political muscles is the lack of further reform since 1999. In the early months of the government, and even the early years, ministers could complain that an unelected chamber had no mandate to meddle in their legislation, and that the chamber instead should be reformed. However, the longer this reform is delayed, the less such arguments sound convincing. If the government really wanted to democratise the Lords it has now had almost ten years to do so. It can be argued that ministers are the last who can complain that the chamber is unelected—if they want it to change then they should introduce a bill to reform it. If this included provision for elected members it would probably have popular support.

These are not my arguments alone. All these justifications for greater assertiveness on the part of the Lords are regularly made in the corridors at Westminster, not least by the peers themselves. The longer time goes on the more they are also entering into the discourse of journalists, other commentators and the general public. These are the things that could make the peers feel more confident—but are they? What is the evidence of this greater confidence?

Evidence of greater confidence

There is mounting evidence, I suggest, both in what the peers say and what they do. The greater assertiveness of the Lords has also been recognised by government, which has sought to act in response.

The first evidence comes from the views of peers themselves. In a parallel survey to that conducted amongst MPs we asked peers whether they believed that reform had made the chamber more legitimate. In total 78 per cent of members of the House of Lords believed that it had. This figure is somewhat suppressed by views of the Conservatives—who had originally opposed reform and are reluctant to now acknowledge that any good came of it. Amongst Labour peers, 88 per cent believed the chamber was more legitimate.[8] Furthermore, peers were strongly supportive of the chamber’s right to block government legislation. Over 90 per cent of them believed the chamber was justified to vote against unpopular government measures, even if they appeared in a manifesto bill. This included over 80 per cent of Labour peers.[9] There seems no doubt, therefore, that peers feel confident in their rights to influence government legislation. Unfortunately we don’t know how they felt before reform, as no such surveys had been conducted. But their belief that legitimacy has grown shows that reform has had an important impact.

This is clear from the public statements of members as well as in their privately confessed views. There are many instances that could be cited from Lords debate. The Liberal Democrats—the third party who now effectively hold the balance of power in most votes in the chamber—have been particularly strident in their views. They have long supported proportional representation for the House of Commons, as they are consistently under-represented there (despite now holding over 60 seats). Liberal Democrat leaders questioned the validity of the 2005 general election, when Labour won a majority of seats on only 35 per cent of the vote. They have repeatedly renounced the convention whereby government manifesto bills are allowed a relatively free passage through the House of Lords, describing this as the product of the bygone age when the chamber was Conservative-dominated and largely made up of hereditary peers.[10] Despite the chamber’s unelected basis they therefore see it as justified to use their position there to stand in the way of government legislation, especially if they have public opinion on their side.

What the peers think is perhaps less important, of course, than what they actually do. How is the greater confidence of the chamber played out in terms of peers’ behaviour and impact on the policy process?

It’s always very difficult to assess the impact of a parliamentary chamber. Quantitative measures tell at best only half the story, and much of the influence goes on in parliamentary corridors and ministerial offices out of public view. But there are some measures we can look at with respect to the House of Lords which are instructive.

There have always been large numbers of amendments made to government bills in the chamber, which can run into thousands per year. But most of these are government amendments, which may result from poorly drafted legislation, or respond to points made when the bill was in the House of Commons, as well as to debates in the House of Lords. Numbers of amendments alone therefore do not tell us very much.

The most obvious measure is the number of defeats the government suffers in the House of Lords, when amendments are passed which are clearly against the government’s wishes. In recent years there have been large numbers of such defeats, and this figure appears to be rising. In the session that ended in early November this year, there were 62 government defeats. In the previous long post-election session in 2001–02 there were 56, and in the 1997–98 session there were 39. In total there have been over 350 government defeats in the chamber since it was reformed in 1999.

Figure 3: Government defeats in the House of Lords, 1975–2006

Figure 3 shows the number of defeats in the chamber in each session since 1975. You can see a rise after 1997, and particularly after 1999. However, this could be interpreted, as it is by some Labour ministers, as simply demonstrating that the House of Lords is more hostile to Labour governments. As you can see, the level of defeats was consistently low during the Conservative years 1979–97—averaging 13 per year—but was exceptionally high during the 1974–79 Labour government, reaching a peak of 126 in its second parliamentary session alone. But although the Lords undoubtedly made life more difficult for Labour governments in the past, I think that we are now seeing a different pattern. If the Conservatives were in government, Labour and the Liberal Democrats would almost certainly combine to defeat them in the Lords, so we would not see a return to the formerly quiet times. However, this cannot be definitively shown until we have a Conservative government.

The number of defeats the government suffers therefore gives some indication of greater assertiveness on the part of the Lords, but is not on its own conclusive proof that the chamber has changed. Another measure that may provide greater evidence is the extent to which the House of Lords is prepared to insist on its amendments. The chamber doesn’t have an absolute veto, and amendments may be overturned once a bill returns to the House of Commons. In this case the bill shuttles back and forth between the chambers until they either agree, or the bill is dropped, or occasionally the government uses its power to bring the bill back in the following session and pass it without the support of the House of Lords.[11]

It’s quite striking that during the 1974–79 Labour government, which included that session with the largest number of government defeats, there were only four bills on which the House of Lords insisted on its amendments. In two cases it insisted once, and then backed down. In one case it insisted twice, and in the last case it insisted three times—meaning that the bill shuttled back and forth three times before the matter was resolved. This was an increase on the record under the previous Labour government, when over the whole period 1964–70, the Lords had only insisted once on an amendment.[12] But it was nothing to the chamber’s behaviour in the first full parliament after its reform in 1999. In the 2001–05 parliament there were insistences on 17 bills. In most cases there was just one insistence before either the Lords backed down or some kind of compromise was reached. In three cases there were two rounds of insistence. But on two bills the chamber insisted on its amendments no fewer than four times, and the same thing has already happened again since 2005, on the government’s proposal to introduce identity cards. This seems a sure sign that the Lords are prepared to throw away the caution that guided them in the past, and stick to their ground when they believe that the government is wrong. They may give in, ultimately, but in the meantime the government faces delay and public exposure on the issues which cause the Lords concern.

These are, as I already suggested, imperfect measures. Counting defeats, or counting insistences by the second chamber does not capture the extent to which the government alters its policy in response to the pressure from the House of Lords. There is no need for the chamber to insist if the government accepts its amendments following a defeat. Our analysis suggests that the government goes at least some way to meet the Lords’ concerns in 60 per cent of cases.[13] There is no need for the Lords to defeat the government in the first place if it is prepared to accept the points raised by peers at earlier stages. A great deal of this goes on and it is very difficult to measure. There is no need for peers to propose amendments at all, if the government seeks to pre-empt their views by putting legislation before the house which is likely to be acceptable. One interesting development in recent years is the extent to which the government is prepared to consult with the Liberal Democrats—who as I say now hold the balance of power in the House of Lords—over key policy proposals. For example when planning its anti-terrorism legislation in 2005 the Liberal Democrats were invited to the negotiating table on the same basis as the Conservatives—a clear recognition of the fact that assent by one or other party is generally required to get a bill through the Lords. In the end, incidentally, it was the Conservatives that were persuaded to support the government on this occasion whilst the Liberal Democrats remained opposed.[14]

Another interesting shift that we have seen recently is a new kind of joint working between members of the Commons and the Lords. On one occasion earlier this year—on a bill seeking to outlaw religious hatred—the Lords made significant amendments, which the government sought to overturn when the bill returned to the House of Commons. But there was much public concern about the bill, and rather than back the government the Commons chose to back the Lords amendments, and the government found itself defeated, as numerous Labour MPs rebelled. On other occasions rebellions during the Commons stages have sent a warning, which has been picked up in the Lords and the legislation changed, with the government choosing to concede rather than face a further Commons rebellion. Several times now Labour dissidents have publicly called upon the Lords to block or amend bills, and clearly much clandestine lobbying also goes on behind the scenes. As a result it seems to be not only the Lords that is strengthening, and certainly not the Lords versus the Commons, but parliament as a whole with respect to the executive.

All of these things seem to provide pretty clear indications that the House of Lords is both feeling more confident, and acting more assertively, following its reform. If one further piece of evidence is needed it can be found in the response of the government. Having started in 1997 by stating that the chamber’s powers were broadly correct, and need not be reformed, many on the government side have moved from supporting a change in the Lords’ composition to a reduction in its powers. This was suggested in Labour’s 2005 election manifesto. Earlier this year, at the government’s instigation, a parliamentary joint committee was established to consider the conventions governing the relationship between the two houses. This reflected growing concerns that the current conventions are breaking down, and is an indication of how the traditional restraint exercised by the House of Lords is seen to be declining, in respect both of primary and secondary legislation. This is what the committee was asked to look at but, after having taken much interesting evidence, it offered the government little comfort when it reported early last month. It suggested that it would be difficult to codify the current conventions, and that these would be bound to change in any case if the composition of the chamber were further reformed.[15]

Prospects for future reform

This leads me to briefly reflect on what these developments suggest for future reform of the House of Lords, before turning to some more general conclusions.

As I said at the start, the government initially promised a two-stage reform, and the norm in the UK is to see House of Lords reform as unfinished business. So much is its current state considered merely temporary, that few bother to look at how the Lords is actually operating. However, we in Britain have a long history of temporary solutions that somehow stick. The reforms in 1911, 1949 and 1958 were all considered shot-term fixes, to be followed by longer-term solutions when the players could reach agreement and parliamentary time could be found. There is every indication that the 1999 reform will prove to be the same.

There are many in the Labour Party who remain committed to Lords reform. However, they remain committed to it for very different reasons. One group wants to deliver on the promise to introduce a ‘more democratic and representative’ house, and to introduce elections. Quite another group wants to reduce the chamber’s powers to make it easier for governments to get their legislation. To some extent this diversity of view with respect to how many checks a second chamber should put on government has always existed in the Labour Party.[16] And to some extent it exists in the Conservative Party too. But more than ever it is now appreciated that the objectives of democratising the Lords and weakening it are fundamentally incompatible. If one seemingly minor compositional change—the long overdue removal of the hereditary peers—results in a chamber which is this much more assertive, there are major concerns in some quarters about the power that would be unleashed by creating an elected chamber. The government is internally divided, and it has been unable to come up with a set of proposals that can secure sufficient support. In 2003 the House of Commons voted on a variety of options for the composition of a second chamber and all of them—ranging from all-elected to all-appointed and five options in between—were rejected by the house. Since 1997 we have had a Royal Commission, two joint committee reports, and we are rumoured to be about to get our fourth government white paper on Lords reform. But I suspect this will go the same way as all the other proposals. In fact the rumours are that the government wants to square the circle by proposing a half elected half appointed chamber—which rather than being welcomed as a compromise is simply likely to be rejected by all sides.

So the Lords composition remains controversial. But the other option that some in the government have floated—a short bill simply to reduce the chamber’s powers—also appears to be politically impossible. Whilst the Lords has the support of the public for its policy interventions this would be a very risky and controversial step, and it would be strongly resisted by the Lords itself. The best chance the government has of reducing the chamber’s formal powers is to package these with compositional changes that will be popular, which means election, which means greater de facto powers.

Probably the likeliest reform is a further minor one, to tidy up the appointments process, reducing the patronage of the prime minister and giving more power to the independent commission which was established in 2000 to oversee appointments. There is growing pressure for this given recent controversies about seats for party donors. However, even this step is seen by some as dangerous as it will further increase the legitimacy of the chamber, and once again its strength. In short the House of Lords has got stronger, but there doesn’t seem to be anything now that the government can do to stop it.

Conclusions

I’m happy to answer questions on reform, but I’d now like to move to my main conclusions, of which I think there are three.

The first is, as the title of this talk suggested, that a little reform can go a long way. Despite the seemingly minor—many would say inadequate—nature of the change to the House of Lords in 1999, power relations have shifted significantly as a result. Reform can have unintended consequences, and those consequences can be bigger than you might expect. We do have prior experience of this in Britain—to some extent the same could be said of the 1958 reform which introduced life peers. This was seen as a short-term fix, but lasted 40 years and in many ways reinvigorated the House, certainly saving it from terminal decline.[17] But it’s particularly ironic that in this case the government sought to strengthen its position by removing a large number of opposition members from the chamber, and in fact seems to have weakened its own position. Here there are clearly parallels with the introduction of PR for the Australian Senate. I have seen this described as a measure introduced for the government’s short-term gain, but it clearly had wide repercussions which saw power shift from government, and also changed both the procedures and the culture of the chamber.

The second big conclusion is about the shape of British politics. We clearly offer the definitive Westminster system, with a strong executive sustained by a single-party majority in the House of Commons, and able between elections to legislate relatively freely—simply facing the wrath of the electors next time round if the wrong decisions are taken. If this ever was true, it may well have been ended by this seemingly minor reform to the Lords. As a result the government is having to negotiate its programme to a far larger degree, and the third party—and independents—have gained an influence in British politics unprecedented in the twentieth century given the size of the government’s Commons majority. Because of the unelected basis of the Lords, and its lesser powers compared to the Commons, it does remain clearly the junior partner. The shift in party power relations is not as stark as it would be if we moved, as many have proposed, to a system of proportional representation for the Commons. Indeed what we are left with is something like what you have experienced in recent decades—a compromise between majoritarian and consensus politics. And we are now likely to remain there. Having achieved the current party balance in the House of Lords there is now an expectation that no party will seek to hold a majority there. This applies in the current appointed house, and it is also a feature of all serious proposals for an elected chamber. As a result small parties and independents look set to grow in influence, making policy making more pluralistic than it has ever been in modern Britain. In addition the balance of power seems to have tilted sharply from executive to parliament, with the House of Commons even working in partnership with the rejuvenated House of Lords. Our one small change has potential to reshape both the party system and the role of parliament in British politics.

The final lesson is one for bicameral studies in general, and runs counter to expectations. It is generally noted that elected chambers are likely to be more powerful than appointed chambers, as appointed chambers will suffer from legitimacy problems. The most complete schema for analysing bicameral strength has been put forward by Arend Lijphart, who notes that ‘[s]econd chambers that are not directly elected lack the democratic legitimacy, and hence the real political influence, that popular election confers.’[18] This may be true all else being equal. But all else rarely is equal, and there are other factors, I conclude, which may be more important. Lijphart’s classification of bicameral strength is based on two factors: the extent to which the powers of the two chambers are symmetrical, and the extent to which their composition has a different representational basis—such as representation of states versus citizens in federal systems. On both these axes the House of Lords is really unchanged by its recent reform—its powers are unaltered, its members continue to represent nobody in a formal sense, and as it is unelected its legitimacy continues to be open to question. Using the same classification system the Australian Senate should also be unchanged by the advent of government control in 2005—the chamber’s constitutional powers remain, as does its system of state representation—which provides a competing democratic legitimacy. In other words your system of bicameralism is strong, and remains equally strong despite recent change, while ours is weak, and remains equally weak. But experience suggests that it’s more complicated than that.

Both examples indicate the importance of the party balance in a second chamber. This in itself is hardly a new finding, although Lijphart doesn’t count it explicitly in his schema. But the story of the House of Lords suggests that party balance, and other factors boosting the perceived legitimacy of a chamber, may actually be more important than whether it is elected and enjoys democratic legitimacy in the traditional sense. In our system the funny old House of Lords with its retired experts and numerous members not taking a party whip has a new appeal as people grow cynical about politicians and political parties. Its relative proportionality has a clear appeal too, given that no government has won a majority of the popular vote since 1931. This is particularly true when, inevitably after almost ten years, disenchantment with the government has become widespread. Despite the chamber’s continued unelected basis, there are therefore important factors which boost its legitimacy in a way that provides it with significant de facto power. The issues of second chamber power, composition and legitimacy are intricately entwined: power flows in part from legitimacy as Lijphart says, but legitimacy may come from places other than those you would immediately think.

It seems strange to say that British politics may be invigorated by an unelected chamber which still contains 92 hereditary peers. As I say, debate in Britain is largely still focussed on the reform of the Lords that hasn’t happened, rather than reform which has. But if, as I suspect, no further reform happens for some time, we may look back in years to come and see that a small and unappreciated reform has changed British politics in very significant ways.

Question — I’m curious about some factual things. Firstly these hereditary peers who have been expelled—I take that they still carry their titles do they? Secondly, the ones who remain, have there been any transfers by the death of one of the remaining ones and does the son become a member of the House of Lords, or does it die?

Meg Russell — The hereditaries that are expelled, yes, they retain their title. So we now have Lords in parliament as well as Lords out of parliament. The ones who remain, there’s a very curious system. Part of the compromise package that enabled the 92 to remain provided for them to be replaced upon death. The way that the 92 were chose, as I said, was an election by their peers. The whole body of hereditary peers elected one tenth roughly of their total to remain the house, and it was done mostly by party groups. So the Conservatives elected the Conservatives who remained and so on.

What they wrote into the Bill was a system of by-elections (so-called). If a hereditary peer who holds a seat in the Lords dies, the hereditary peers who remain elect a successor and the successor has to be drawn from the current body of hereditary peers outside the House. So he could be an expelled hereditary peer or the son of a hereditary peer who has died, not necessarily the one who departed the House. It is a very bizarre system and I think people in government are really regretful that they agreed to that element of the compromise. They agreed to it because people, I think, genuinely thought that the next stage of reform was coming, the by-election system would never be used, but we’ve now had about six or seven of these.

Question — Does that mean that some peers holding their titles were in the House of Lords then went out of the House of Lords and will never come back in again?

Meg Russell — Yes. Some have come back. I think one son of a peer who left and then died has come in. I think it’s likely that at some time there will be a private members bill or something to end the by-elections. If we ended the by-elections, it would take quite some time for them all to die off; the youngest hereditary peer is younger than me. Eventually they would go by natural wastage. At the moment the 92 are constantly topped up.

Question — I wonder if the lesson from what you say is that, if any fundamental reform of parliament is to take place, it has to take place immediately a government comes into office and before disillusionment or cynicism sets in.

Meg Russell — I think that’s quite right and I think it’s the case with all of the constitutional reform that we had. It’s interesting that in the first two parliaments after Labour came to power in 1997, we had a huge raft of constitutional legislation, not all of which I mentioned. One of the reasons for that was that the Labour Party had committed itself to not expanding welfare programs. It had committed itself to sticking to conservative spending targets and therefore there wasn’t that much on the social welfare front that it could do. So it put all its constitutional reform very quickly, which was all very radical. I think if it had waited a bit longer, if it had had other things to do in its first and second term, some of these things might never have happened.

What we are waiting for now is two things. One is a change of government (though I believe that the Conservative leader has suggested in private that House of Lords reform is really not a big priority for him). Some of the Labour peers are coming to realise that they can team up with the Liberal Democrats and defeat the Conservatives when the Conservatives come to power, and that might actually be quite fun. It’s at that point that people will really appreciate that the House of Lords has changed—when it becomes an instrument for a coalition of the left to defeat a Conservative government. But people are quite slow to realise this and I think that includes the Conservative leader. The Conservatives still have this idea that the House of Lords is their friend, and so I think Lords reform by an incoming Conservative government is quite unlikely. The other thing we are waiting for is Tony Blair’s retirement, and there are all sorts of rumours about what Gordon Brown who is expected to succeed him wants to do. But Tony Blair was very keen on Lords reform before he was prime minister. Gordon Brown has had very little legislation because he’s Treasury Minister. Those ministers who have had a lot of legislation are very wary of anything that strengthens the Lord’s powers.

Question — I got an overwhelming impression that there is a lot of ferment going on from your statements. You mentioned the Scots, the Welsh, you mentioned small parties, and Independents.

Meg Russell — There are all sorts of interesting debates in Britain about England at the moment about parliament and the position of Scottish, Welsh and English MPs in parliament, because now we have devolution in Scotland and Wales and no devolution in England. There is quite a lot of controversy about Scottish MPs voting at Westminster on matters which apply only to England, because of course we don’t have a federal arrangement. The largest part of our union state, England, which represents 80 per cent of the population, has no devolution at all. So we have a great imbalance.

Question — Has unicameralism ever been given a serious run at all? You’ve also partly answered a question which I was going to ask—the 1911 Parliament Act. To what extent has consideration been given to removing the restrictions and becoming more powerful, as distinct from the way you were characterising it. A consequence of an appointed house is that there is a quality of people and a variety of people in a chamber that you don’t get from an elected house and I in fact had the privilege of sitting through the first debate on embryo research in the House of Lords and the quality of debate was superb. I’m wondering how much that gets attention.

Meg Russell — You are inviting me to write another speech with all those questions. Unicameralism was originally the Labor Party’s position on its foundation, but curiously when the party found itself in government, it never was that inclined to put this into effect. The time when it might have done so was in the 1940s when it had won a landslide after the Second World War, but it wanted to put through so much legislation in that period that Labor ministers came to appreciate that the House of Lords could be turned into a legislation factory and they could introduce bills into two houses at once. They could put the uncontroversial things in there and the peers would all work on the detail. Actually abolition never seriously came onto the agenda even in that period. The Labour Party last had a commitment to abolish the House of Lords in its 1983 election manifesto, which was highly controversial. That was a manifesto which the left of the Party managed to seize control over and wasn’t really representative of the post-war Labour Party.

Unicameralism was one of the positions that the House of Commons voted on in 2003. It was presented with seven options for reform and a group of Labour back-benchers put down a unicameralist amendment, but that was quite heavily defeated alongside all the rest. So it’s not a real option. Just as I think increasing the Lord’s powers are not a real option. There was general consensus until very recently that the way the Lords’ powers have settled after the 1911 and 1949 Parliament Act was about right. A year’s delay—it’s a slightly messy system, it’s not really a year’s delay, it’s untidy, but this was broadly about right, and it’s actually only the Labour Party or certain elements of the Labour Party ministers who have wanted to unpick that and suggest that the powers might be capped.

You are quite right about the issues of quality and expertise and variety and independence of mind as well, and maturity, and all the rest of it that goes along with the appointed House. In a sense I think I didn’t play that up very much, but that is one of the things which contributes to this sense of its new legitimacy that the existence of those factors was perhaps rather masked by the overwhelming preponderance of hereditary peers. Now that those peers have been taken away, they reveal the life peers and we’re now in this period when people, as I said, are feeling rather cynical about political parties. They don’t like all the yahoo politics of the House of Commons and they quite like the idea of these rather other-worldly, mature expert people who come along and chip in as you say, on some very delicate debates in ways which are widely respected.

* This paper was presented as a lecture in the Department of the Senate Occasional Lecture Series at Parliament House on 8 December 2006.

[1] This research was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) under grant RES-000-23-0597. I am grateful for their support.

[2] Words taken from the preamble of the 1911 Parliament Act.

[3] See D. Shell, ‘Labour and the House of Lords: a case study in constitutional reform’, Parliamentary Affairs vol. 52, no. 4, 2000, pp. 429–441.

[4] These figures exclude the 119 hereditary members who had either not taken the oath or were on leave of absence. Of the remainder, 217 sat on the crossbenches and 22 as Liberal Democrats.

[5] Baroness Jay, House of Lords Hansard, 14 October 1998, col. 925.

[6] For full results see M. Russell and M. Sciara, ‘Legitimacy and Bicameral Strength: A Case Study of the House of Lords’, Paper to 2006 Conference of the Political Studies Association specialist group on Parliaments and Legislatures, University of Sheffield. Available at: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/constitution-unit/research/Parliament/house-of-lords.html.

[7] Ibid. This survey was carried out only three weeks after the 2005 general election.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] See for example the speech by then party leader Charles Kennedy at House of Commons Debates, 17 May 2005, cols 50–51.

[11] The Parliament Acts, allowing a bill to pass with the support of the Commons alone, have actually only run their full course on four occasions since 1949.

[12] Janet Morgan, The House of Lords and the Labour Government 1964–70, Oxford, England, Clarendon Press, 1975.

[13] For a preliminary analysis see M. Russell and M. Sciara, ‘Why does the Government get Defeated in the House of Lords?’, Paper presented to the Political Studies Association Conference, University of Reading, 2006. Available at: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/constitution-unit/research/parliament/house-of-lords.html

[14] See M. Russell and M. Sciara, ‘The House of Lords in 2005: A More Representative and Assertive Chamber?’ in M. Rush and P. Giddings (eds), The Palgrave Review of British Politics, 2005. Basingstoke, England, Palgrave, 2006. This chapter is also published as a briefing by the Constitution Unit: see website address at note 13.

[15] See Joint Committee on Conventions, Conventions of the UK Parliament, Report of Session 2005–06, HL 265, November 2006.

[16] See P. Dorey, ‘1949, 1969, 1999: The Labour Party and House of Lords reform’, Parliamentary Affairs, vol. 59, no. 4, 2006, pp. 599–620.

[17] For a discussion see Janet Morgan, op. cit.

[18] A. Lijphart, Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries. New Haven, CT, Yale University Press, 1999, p. 206.

Prev | Contents | Next

Back to top