Papers on Parliament No. 39

December 2002

Prev | Contents | Next

The term ‘independent’ has good associations. It triggers thoughts of self-reliance, freedom, and open-mindedness. But, if the word is linked with ‘candidate’ at election time, the reaction may not be as favourable. For most voters, an independent candidate is an anomaly, to be seen as one of the names on the ballot to be ignored, or viewed as a crank who is making a fruitless protest in a party dominated world. For activist members of the large parties, the response may even be hostile; independent candidates can confuse the flow of votes in close electoral contests. Many independent candidates have previously been members of a party and may be running at the election to challenge their past associates and to voice their dissatisfaction with their former party. And if the word ‘independent’ is linked with ‘member of Parliament’, strong and usually unfavourable reactions will be found among members of Parliament who represent the large parties. This will especially be the case for members of the governing party if the support of an independent member is required to keep the government in office. In these circumstances, the response is one of apprehension and resentment.

These varying responses tell us a little about the place of the independent in the political process but there are many questions which need to be resolved. What are independent candidates independent of? What is the relationship between independents and political parties, large and small? Why do independents run for office and what determines their electoral success? Are they a new phenomenon? What is their significance for the process of representative government? And what explains the recent increase in the number of independent candidates and members of Parliament?

It is this last question which has made independents an issue for both political parties and political scientists. In May 2002, there were 25 members of the lower houses of state and Commonwealth parliaments who were elected at general elections as independents.[1] This is equal to the largest number of such members since the current party system emerged around 1910. The figure was matched early in 1941 when the then major conservative party, the United Australia Party, was beginning its process of dissolution. But in 1941, 12 of the independents were members of the South Australian House of Assembly, and only one had been elected to the House of Representatives. Now, the House of Representatives and all state parliaments except Tasmania have between 3 and 5 independent members elected to the lower house. Of most significance for the largest parties, all parliaments except the Commonwealth Parliament have seen periods of minority government over the last fifteen years, with most of these being dependent on the support of one or more members of the lower house who were elected as independents. This is why independents are a hot political topic.

Two factors have combined to produce this result and enhance the political salience of independents. The first is a trend which has been visible for a number of years. In the ten years from 1993 to 2002, 44 independents were elected to state and Commonwealth lower houses. This is more than double the number elected in the previous ten years (19), and more than three times the number in the ten years before that (14). The second factor is the decline in the combined vote share of the largest two parties at general elections. The average for all state and Commonwealth lower houses has dropped by more than 10 percent over the last decade, from 85.4 percent to 74.4 percent, a decline which has been distributed fairly evenly between the Australian Labor Party and the Liberal Party. The combination of these factors has led both to an increased likelihood that independents will be elected, and to the possibility that such members will hold the balance of power.

The meaning of independent

Before looking at explanations for these changes, we should return to some of the basic questions about independents. The most fundamental of these is: ‘What is an independent?’ This is a question which is surprisingly difficult to answer. An independent is someone who is not associated with a political party. This is fine as far as it goes, but what is it about a political party, the absence of which defines an independent? There are two ways in which this question can be dealt with. The first is to say that an independent candidate is someone who runs for election without a party label. Electoral laws are blurring this distinction because, if having a party label means having a party affiliation listed on the ballot paper, only members of registered parties can have party labels. Candidates of non-registered parties are not independents even if they have no label on the ballot. But this distinction aside, an independent candidate for an election is reasonably easy to define. He or she is someone who refuses to run with a party label and seeks the support of voters because of the candidate’s personal political values rather than those of a party.

The second approach is to ask: ‘What is an independent member of Parliament?’ Here the party label—or lack of label—with which a member has been elected is less important that the member’s behaviour in Parliament. If a member refuses to be bound to vote with a fixed bloc of members, he or she is said to be an independent. Such representatives are not members of a parliamentary party or caucus and can vote on measures in Parliament as their own political judgement dictates. Many independents start their life in reaction to the pressures of being a member of a parliamentary party. They have had a disagreement with their party and decide to leave the caucus, sit as independents and vote in Parliament as they, rather than the party, choose.

If we put these two characteristics together, we have an independent as someone who runs for office without a party label on the understanding that he or she will not be bound by any party affiliation when voting in parliament. In both aspects, independents are distinguishable from members of parties, particularly the disciplined parties which have dominated Australian politics since 1910. In these parties, the ability for a candidate to use the party label at election time is granted on the condition that, if the candidate is elected, he or she promises to follow the decisions of the parliamentary party or caucus in casting a vote. This undertaking is explicit in the Australia Labor Party, and implicit—but hardly less binding—in the Liberal Party.

This contrast means that independents are defined by their aversion to the discipline of the modern party. But it also means that independents have much in common with the members of the loose party groupings which characterised Australian politics from the granting of self-government in the 1850s until about 1910. Such party groupings or factions were linked by shared values, commitment to similar policies, admiration of a particular leader, as well as the hope of holding office.[2] They formed fluid coalitions in parliament, the largest of which would support the government of the day and were often called, for that reason, ministerialists. At election time, candidates were elected because they and their policy orientations were well known in the local community rather than because of a party affiliation. Their campaigns relied on supporters who would form an organisation which would operate during the election period but would cease to exist between elections. Above all, these members represented geographically defined communities. The party groupings with which they were often associated in parliament have been called parties of notables, reflecting the dominance of personality and locality in the election of representatives. The continuing theme of community politics is the defining characteristic of today’s independents. As such, independents are the heirs of the pre-modern party of notables, representing a small but persistent reaction against the dominance of contemporary party driven politics, both in the electorate and in parliament.

Other reactions against party politics

Independents are not the only manifestation of dissatisfaction with modern party politics. If modern party politics is taken to be synonymous with the politics of the two largest parties, Labor and Liberal, the most important sign of disaffection has been the rise of minor parties. In recent times, it has been such parties as the Australian Democrats, the Greens and the meteoric rise and fall of Pauline Hanson’s One Nation Party which have been the biggest factor in reducing the vote share of the largest two parties. There are several explanations for the rise of these new parties based on social and economic change, but three political themes predominate. The first is a protest against the limited policy choice offered by the large parties; the second is a concern with a particular set of issues centred around such areas as the environment or immigration; and the third is an aversion to the apparent dominance of party elites in manipulating both parliamentarians and the political process.

This last theme is one shared with independents, but the remedy offered by minor parties differs significantly from that offered by independents. For the Australian Democrats, the influence of the party machine is countered by stressing the involvement of rank and file members in all critical decisions made by the party. Policy direction, the choice of candidates and even the choice of leader are open to postal ballots by all members of the party. In addition, parliamentary members of the Democrats are not bound to vote with their colleagues if they disagree over measures before parliament.

The Greens take a different tack, putting stress on extensive consultation with members of the party at the local level. Dissatisfaction with those controlling existing parties was a major element in the original appeal of the One Nation Party, even though the party began with no policy for democratising its own structure and problems with membership of the party led to serious legal difficulties with electoral commissions over its registration as a party.

In some respects, minor parties represent the antithesis of the protest against big party politics made by independents. The support for minor parties is spread, albeit unevenly, across the whole electorate and their focus for representation is on those institutions which use proportional representation for the election of members. Such an electoral system permits the representation of parties or single issue groups which have system-wide support above a certain level, but whose votes are never sufficiently concentrated in one particular geographical district to elect a member under a single member district system. This has meant that small parties see their power base as being in the Senate and the upper houses of New South Wales, South Australia and Western Australia, all of which use variants of proportional representation. Tasmania, as is often the case, provides multiple exceptions which will get separate treatment but, Tasmania aside, small parties and single-issue groups rely on system-wide support and aim for representation in upper houses.

Independents, by contrast, live or die by the support of a narrowly defined community. As all state and Commonwealth lower houses except Tasmania use single member districts to elect their members, this means that independents are a direct challenge to the ability of the big parties to secure majorities where they count most, in the lower houses of parliament where governments are formed. The result is that, while minor parties are a nuisance, independents can be a more serious and direct threat to the aspirations of the big parties to form government.

Before exploring this further, we should note another, and once common, way of resisting the organisational limitations of the major parties. This was to run under a label which had the word ‘independent’ in front of a party name. The idea was to signal the general policy and ideological stance of the candidate, but to indicate that the candidate would not necessarily be bound by the party caucus in parliament. It should be added that this remedy was often used by candidates who had had a falling out with their party, or had not been able to secure party endorsement as a candidate. These semi-independent candidates have existed in state and federal elections over the last hundred years, although they were more common in the first half of the last century. South Australia has been an exception in that such candidates have persisted until recently; two Independent Labor members of the South Australian House of Assembly were elected in 1985 and 1989, and held the balance of power in the Bannon minority government which took office in 1989. Independent Liberals have also been elected, one in 1985 and another in 1997.

The major parties dislike such candidates because the ‘independent’ addition to the party name provides an open invitation for disgruntled members of their parties to run against endorsed candidates. As a consequence, the major parties in most jurisdictions have conspired to preclude the label ‘independent’ from being added to the name of a registered party.

But the large parties cannot control what independents choose to call themselves in parliament. In the Western Australian Legislative Assembly, two candidates who were elected in 2001 as independents wish to be known as ‘Independent Liberals’. Both were originally members of the Liberal Party and both have established themselves as independents and been re-elected at general elections as independents. Both, however, wish to indicate their continuing dissatisfaction with the organisation of the Western Australian Liberal Party by calling themselves Independent Liberals in parliament.

It should be noted that whenever data for independents are referred to in this presentation, only figures for genuine independents are used—candidates running under a party name with ‘independent’ added in front of it, are excluded. In addition, independents are only counted if they are elected as such at a general election—members who defect from their party after being elected on a party label or who were elected at a by-election are excluded. Similarly, no account is taken of what independents call themselves once they are elected. While on the topic of disclaimers, I should point out that collecting information on elections for a period of a century always involves dealing with anomalous cases. But these idiosyncrasies have little effect on the broad patterns of voting and representation.

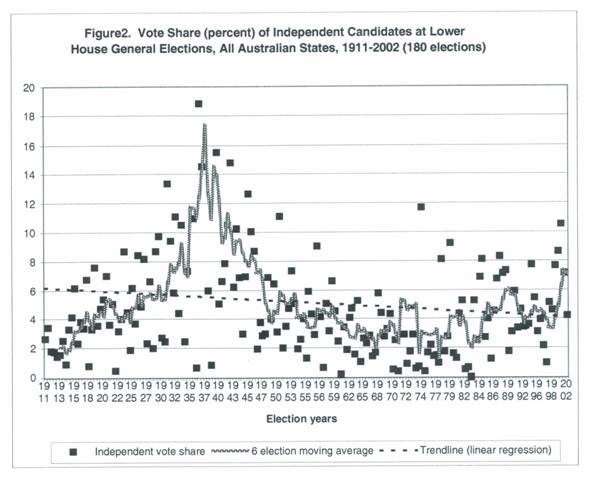

Independents and House of Representative elections since 1996

If we return to the community politics of independents, we are still left with questions. While the unfavourable reaction to party politics may be understandable, support for independents has been only a very minor theme in Australian politics even if one which has shown recent growth. The long term vote share for independents at all state and Commonwealth lower house general elections since 1911 has averaged just under 4½ percent. As we shall see, this varies by parliament but in no lower house has the average exceeded 5½ percent. What is it about some candidates and electoral districts that enables an occasional independent to capture enough votes to win a seat? How, in other words, do independents get elected when their system-wide support is so low?

At the 2001 federal election, 1039 candidates were nominated for the 150 electoral districts which make up the House of Representatives; 113 (10.9 percent) were listed as independents and another 30 ran without a registered party name. Of all these, only three independents were elected—Peter Andren and Tony Windsor from rural New South Wales, and Bob Katter from rural Queensland. In an excellent chapter by David Solomon in the book which he edited, Howard’s Race: Winning the Unwinnable Election,[3] Solomon looks at the circumstances under which these three candidates were elected. He points to a number of shared characteristics. At the 2001 election, all three had already had experience as parliamentarians; Andren as a sitting member who first won his House of Representatives seat in 1996, Katter who had been a long time representative of the National Party in both the Queensland and federal parliaments, and Windsor who had been an independent member of the New South Wales Parliament for about ten years.

Being a local political notable clearly helps in getting elected, and Andren’s success at his initial election in 1996 would have been greatly assisted by his being a local television presenter. All three had won what were once regarded as safe National Party seats, and Solomon notes that two of three, Katter and Windsor, had been members of the National Party. The disruptive effect of the One Nation Party, claims about the ineffectual role of the National Party in protecting rural interests, and disillusionment with party politicians in general are all referred to by Solomon as reasons for the election of these three independents.

The feeling of being let down by the major parties appears as a continuing theme in the success of independents. This is borne out in a helpful survey by Scott Bennett (1999) in a research paper prepared for the Commonwealth Parliamentary Library.[4] If we go back to the 1996 election, four of the five independents elected to the House of Representatives in 1996 were contesting seats without the endorsement of parties of which they had previously been members. Graeme Campbell had been disendorsed by the Labor Party for the seat of Kalgoorlie; two former representatives from metropolitan Perth, Paul Filing and Alan Rocher, had been disendorsed by the Liberal Party; and Pauline Hanson had her endorsement as the Liberal candidate for Oxley withdrawn shortly before the election.

Of these four, Campbell and Hanson were maverick members of their parties espousing views which gave the party little choice but to expel them, and Filing and Rocher had been on the wrong end of intra-party struggles which had cost them their party endorsement. The factional disputes within the Western Australian Liberal Party brought the party into disrepute and goes much of the way to explaining how Filing and Rocher were able to win their seats against endorsed Liberal Party candidates.

All four of these independent candidates claimed that party organisations were out of touch and needed to listen to the real interests of the local community. But, as Solomon notes for the 2001 election, there were several independent candidates who could make these claims and appeared to have a good chance of getting elected but, in the event, did not win many votes. The explanation would seem to be that, to get elected, an independent needs both a high local profile through community engagement, and a degree of ineptitude on the part of the major party which has normally held the seat. If the Labor and Liberal parties had anticipated the problems which surfaced with the endorsement of the four candidates who ran successfully as independents in 1996, it is possible that none of them would have been elected

Notoriety over disagreement with a former party is apparently only good for one election as an independent to the Houses of Representatives. The only two independents to be re-elected as independents at general elections since 1945 have been candidates who could not have been seen simply as party renegades: Ted Mack as a former Mayor and member of the New South Wales parliament, elected to the House of Representatives in 1990 and 1993; and Peter Andren in 1996, 1998 and 2001.

Systemic explanations

Can we now answer the question of what it is about an independent candidate or the electoral district that enables an independent to be elected? There are some suggestions in the anecdotal evidence from the last three federal elections but, as all the commentators have pointed out, the election of independents to the House of Representatives is far from typical. And some of the evidence is contradictory; in 2001, the independents were all from rural electoral districts and two of the three had links with the National Party; but in 1996 two of the five were from suburban electoral districts, three were unendorsed Liberals and one was an unendorsed member of the Labor Party. And no independents were elected between 1966 and 1990.

There are good reasons to think that the House of Representatives is not the place to expect independent members or to find reasons for their occurrence. The first reason is that the day to day issues affecting people’s lives are almost all within the administrative responsibility of the states. The Commonwealth may have grandiose plans and transfer lots of money to the states, but the actual administration of everything from hospitals and schools to the police, local government, the criminal law and the rules for land use and zoning are all state responsibilities. If community is the key, things that matter to the community are state and local issues, not federal ones.

The second reason is related to size. If we take all those electors entitled to vote at a general election for a parliamentary chamber and divide this number by the number of members in the chamber, we get the average number of electors to be represented by each member. If we average this number for each state and Commonwealth lower house since 1911, we get an idea of the relative representativeness of each chamber over the whole period from 1911–2001. The average enrolment for each House of Representatives member in this period is more than twice the average number for the lower houses of the New South Wales and Victorian parliaments, more than four times the Queensland and South Australian parliamentary averages, six times the Western Australian average and more than nine times the number for the Tasmanian lower house.

Table: Vote share and number of independents elected at general elections,

Australian state lower houses and the Commonwealth Parliament, 1911–2001

|

Legislative chamber

|

Number of elections in period

1911–2001

|

Mean vote share of independents*

|

Number of independents elected

|

Elections with one or more independents elected

|

Average electoral enrolment per member of chamber

|

|

|

|

mean

|

range

|

|

|

|

|

n

|

%

|

%

|

n

|

n

|

%

|

n

|

|

State lower houses

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

New South Wales

|

30

|

4.8

|

2.2

|

0-8

|

25

|

83.3

|

22 893

|

|

Queensland

|

32

|

3.9

|

1.2

|

0-5

|

19

|

59.4

|

12 205

|

|

South Australia

|

30

|

5.5

|

1.7

|

0-12

|

18

|

60.0

|

12 315

|

|

Tasmania

|

28

|

4.5

|

0.8

|

0-3

|

14

|

50.0

|

5 857

|

|

Victoria

|

32

|

4.8

|

1.5

|

0-6

|

23

|

71.9

|

21 503

|

|

Western Australia

|

29

|

5.3

|

1.0

|

0-4

|

12

|

41.4

|

8 796

|

|

All states mean

|

30.2

|

4.8

|

1.4

|

na

|

18.5

|

61.3

|

13 928

|

|

Commonwealth

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

House of Representatives

|

36

|

2.3

|

0.6

|

0-5

|

15

|

41.7

|

54 862

|

|

Senate (1949–2001, excluding territories)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Whole chamber

|

21

|

0.7

|

0.5

|

0-2

|

10

|

47.6

|

123 993

|

|

NSW senators

|

21

|

0.4

|

0.0

|

0

|

0

|

0.0

|

276 0 34

|

|

Tasmanian senators

|

21

|

7.9

|

0.5

|

0-1

|

10

|

47.6

|

26 736

|

- Independents are treated as a single party grouping and their vote share at general elections is included only if it exceeds 2 percent of the first preference vote. See text for the definition of independent and related issues.

Source: Calculated from the Australian Government and Politics Database, Department of Political Science, University of Western Australia

It is assumed that the smaller the number of electors per member, the easier it should be for an independent to become identified with the interests of one or a small number of communities. In turn, this would allow an independent candidate to contrast his or her concern with local issues with party representatives who were bound by a party organisation and a party platform. So, the larger the enrolment for each member of the lower house, the fewer independents should be elected.

If we look at the aggregate data for all state and Commonwealth lower house general elections from 1911, the expected pattern appears for the House of Representatives. This chamber has the largest average number of voters per member but the lowest average vote share for independents for any lower house (close to half of the next lowest) and the smallest average number of independents elected over the period.

So far so good, but this explanation does not help to make sense of the variations between the states. New South Wales has the largest average enrolment per member of all state lower houses and yet has the highest score for almost all the indicators of success for independents. One or more independents has been elected at 25 of the 30 general elections (83.3 percent) for the New South Wales Legislative Assembly since 1911 with an average of 2.2 independents being elected at every election, both of these figures being significantly higher than those for any other state. These scores are in spite of the New South Wales average vote for independents being equal to the average for all states.

Still more puzzling is the case of Tasmania. This state has by far the smallest average enrolment for each member of its House of Assembly yet it has the lowest figure for the average number of independents elected and the second lowest score for the number of elections at which an independent was elected. It is also the most decentralised state with a large number of regional communities committed to protecting local interests. Perhaps Tasmania holds the key to explaining the existence, or rather the absence, of independent members of parliament.

Tasmania—exceptions proving several rules

Tasmania is the federation’s smallest state both in geographical size and in population. It has a little over 330 000 voters currently on the electoral roll for state and federal elections. Returning to the figures about representativeness, the state has had the smallest average number of electors for each member of the state lower house, the House of Assembly, over the period since 1910. The knowledgeable among you will be bursting to tell me that this is not a fair comparison because, since 1909, the Tasmanian lower house has been elected by the single transferable vote method of proportional representation (PR-STV). Members of the House of Assembly are elected from five multimember districts returning first 6, then 7 and now 5 members from each district.

But this accentuates the problem. Proportional representation is supposed to work in favour of the election of any small party and independent candidates who can secure support above a quota for representation. Why has there not been a swag of non-major party representatives in Tasmania?

Investigating the reasons for this puzzle was the object of a research project two colleagues and I undertook some years ago.[5] Briefly, the answer is that Tasmania adopted PR-STV before the emergence of modern mass parties. When these parties did become dominant, they had to adapt to a system of representation which put a great deal of stress on the personal political appeal of members. Party candidates were not simply chosen because they had a party label but because they also had local support as individuals. Party groupings in such a system can be seen as teams of independents who happen to share the same party label. This has been reinforced by electoral rules which prevent the parties from ranking candidates in a party list, and ban how to vote cards which tell the voter of a party preferred order of candidates. The result is that each member on a party ticket is running as much against his or her team mates as against the opposing teams. It also means that the voter can vote consistently for a single party but vary the ranking of particular candidates. The result is that the Tasmanian House of Assembly has a high rate of turnover of members—members must continually prove to the electors that they are doing a good job or else they are dropped by the voters. In such a system, there is no demand for independents—everyone is a quasi-independent.

In the years from 1890 until 1909 there had been many independents elected to the Tasmanian House of Assembly but all this changed with the adoption of proportional representation. Candidates running in teams were more likely to benefit from the exchange of preferences so that there were inducements to form party groupings rather than running as an ungrouped independent. The party groupings of Labor and Liberal have been very successful, but their origins mean that Tasmanian parties are very different creatures from those on the mainland. This difference points to the conclusion that, if large parties can incorporate a high degree of candidate responsiveness to local issues, such parties are largely proof against both the election of independent candidates, and the defection of party members to sit as independents after they are elected.

Tasmania has two other idiosyncrasies to explore. The first is its upper house, the Legislative Council. This chamber is full of independents and has been for the last century. Party members have been elected, but the largest single grouping for almost the entire period has been independents. The chamber of, until recently 19, now 15 members, has been elected from single member districts by rotation which means that the chamber has never had a general election. Here the regional nature of Tasmania is graphically displayed with the politics of locality and personality fought out in the upper house. The experience of the Legislative Council confirms the conclusion that the absence of independents in the Tasmanian lower house reflects the way the electoral system encourages large parties to incorporate local sensitivities through the process of selecting of candidates.

The Senate

Before moving to re-examine independents in other state lower houses, we should consider the last of the Tasmanian exceptions which involves the Senate.

I should say at this point that I have not examined other state upper houses as part of this investigation into the role of independents. One reason for this omission is that comprehensive information on the patterns of representation for state upper houses is not as readily available as it is for lower houses. The more important reason, however, is that state upper houses have gone through several transformations over the last century both as to their systems of representation and their role in the parliamentary process. This factor and the large variations between states makes systematic comparison of state upper houses a topic on its own, a task that I understand my colleague, Dr Bruce Stone, will undertake in a Senate occasional lecture later this year.[6]

The Senate is a different matter, although it illustrates the major structural changes which can affect upper houses in Australia. It is now famous for its role since the 1960s as a chamber in which PR-STV has enabled minor party and independent senators to hold the balance of power in the chamber.[7] These senators use their influence to improve the quality of legislation and to enhance the parliamentary scrutiny of the Commonwealth government. Does this situation amount to a contradiction of the generalisations about independents derived from looking at the operation of PR-STV in the Tasmanian lower house? I do not believe that it does.

To begin with, the adoption of PR-STV for the election of senators from the 1949 election marks a major discontinuity in the composition of the Senate and it is only from this date that comparisons are made. Taking this period of 21 elections from 1949 until the present, the Senate has the lowest score for the representation of independents for any chamber. Of these 21 elections, there have been ten at which one or more independents have been elected. At every one of these ten elections, an independent senator has been elected from Tasmania, and on only two occasions has any other state provided an independent senator. These two exceptions were Senator Negus in 1970, and Senator Valentine (running as the Valentine Peace Group) in 1984. Both these non-Tasmanians were from Western Australia and both ran more as single-issue candidates than as independents. Syd Negus campaigned for the abolition of death duties, and Jo Valentine for anti-nuclear, peace and green issues on which she had previously been elected to the Senate as a member of the Nuclear Disarmament Party. And both Western Australians were elected only once on an independent ticket.

Compare the Tasmanians. All were elected as independents more than once: Reginald Turnbull twice, Michael Townley twice and Brian Harradine a remarkable six times. All had previously been members of one of the large parties: Turnbull had been a Labor MHA in the Tasmanian Parliament; Townley had failed to gain Liberal preselection for a House of Representatives seat (he eventually gained endorsement as a Liberal Senate candidate in 1975); and Harradine had been a major player in Labor Party and trade union politics.

How can this Tasmanian anomaly be explained? First, as we have seen, Tasmania is used to the politics of personality and locality. Secondly, the fact that Tasmania has equal representation in the Senate but has the smallest number of voters of any state, means that the average electoral enrolment per senator in Tasmania is about half the average for a House of Representatives seat, about a fifth of the national average for the Senate, and less than ten percent of the average for New South Wales senators (see Table). The result is that the number of votes required to get elected to the Senate in Tasmania at a regular half-Senate election is comparable with the number of votes to get elected to a House of Representatives seat. Senator Harradine, for example, won fewer than 25 000 primary votes in 1998, a number well below that required for winning most House of Representatives seats. So, the size principle is at work.

Senator Harradine and his Tasmanian predecessors have been able to generate enough identification from a community of supporters to gain representation. This is very much more difficult for independents running for the Senate as independents in any other state. In 1998, a comparable share of the vote in South Australia, the next largest state, would require three times the number of votes. Perhaps Tasmania isn’t so much of an anomaly after all. It just uses the resources in which it is particularly rich—its small population size relative to its representation, its brokerage skills and a strong sense of local identity—to best advantage. A final paradox can be noted about the Senate. It is not a chamber whose design is compatible with electing independents, but it is one with a structure and composition which provides strong inducements for disaffected members of the large parties to sit as independents. The brokerage power of a Senator Colston, for example, is very large. If there are independents in the Senate in the future, they are likely to have been elected as members of a party and moved to the cross benches at some time after their election. A current example is Senator Shayne Murphy from Tasmania who left the ALP to sit as an independent in 2001.

Explaining independents

The digressions to Tasmania and the Senate may have provided some information for a general explanation as to why some independents get elected. We have already established that an independent candidate must have a strong engagement with a local community and a high local profile, preferably one associated with political activity. Secondly, the candidate must have an objection to the kind of party discipline required of candidates for the major political parties. But the Tasmanian case stresses the importance of a third factor. The dominant major political party in the district contested by the independent must have a candidate selection procedure which does not accommodate local preferences. This factor can take two forms. It may result from strife in the local branch of the dominant party in the district; a fight over preselection between two local candidates, or resentment over a candidate from outside the district being parachuted in by the central party organisation. Or it may be a consequence, in the case of Liberal and National party candidates, of attempts by the party hierarchy to prevent a candidate from one of these parties being endorsed to run against the other.

Another situation where local preferences are not accommodated is one in which the dominant major party in the district has become locked into policies which are seen to run against local interests. This is a particular hazard for rural districts represented by the National Party where the party is in coalition with the Liberals. Rural voters may feel betrayed by the compromises made by National Party parliamentarians in the interest of being a part of a coalition government. Such tensions have twice split the National Party in Western Australia over the last 80 years, and may go some of the way to explain the persistence of independents from rural areas of New South Wales. The coalition between Liberals and Nationals in New South Wales is the most consistent and long lasting of any state and the cost of the permanence of the coalition may be a relatively higher frequency of rural independent members in the state parliament.

This leads to a broader observation about the relationship between major party structure and the number of independent candidates. If the control of major parties is strongly centralised or shaped by factional politics, the ability of such parties to respond to local concerns is compromised. Without looking at the details of New South Wales party politics, it is tempting to speculate that this state has seen more than its share of factional politics and intra-party strife in both the Labor and Liberal parties. This may be another explanation for New South Wales being the state which has been the most prone to elect independents over the period since 1911.

This also suggests that the reason for the recent general increase in the number of independent candidates and members of parliament may have a lot to do with the current nature of the major political parties. These parties are going through a transformation in which they are moving from an organisational structure heavily dependent on a mass membership to one where an active membership is much less important for the success of the party. Over the last twenty years, an increasing proportion of party functions have been sub-contracted to separate agencies. Party policy is now strongly shaped by public opinion polling, campaigning by professional image makers, public relations by experts in the manipulation of the news media, and fund raising by agencies skilled in targeting the relevant interest groups. Government funding of political parties at elections and the increasingly complex rules for the registration of parties and the disclosure of expenditure are making parties look more like state agencies than voluntary associations. All this has increased the need for central coordination of political parties and enhanced the influence of the parliamentary leadership and the party elites who are responsible for running the semi-corporate structures which the large parties have become.

This leaves the local member of parliament bound to support a hierarchy over which he or she has little control. In addition, the process of candidate selection by the major parties is seen by them as one of the recruitment of talent for the party rather than as the selection of agents who can best representing local interests. Such a situation goes a long way to explain why there is a diminishing attraction for people to join political parties other than as activists interested in gaining party office. It also explains why independent candidates are making increasing inroads into the vote share of the large parties. Independents can draw an increasingly stark picture of the cartel-like nature of the major parties and their difficulty in responding to local concerns.

Source: Calculated from information from the Australian Government and Politics database, University of Western Australia

The proportion of the vote for independents is still small but there is a final point that the large parties should note. The last time the number of independents elected and their average share of the votes and seats was as high as it is at present, and rising, was in the 1930s (see Figures 1 and 2). This was associated with major realignments in the party system and a period of considerable volatility in party politics. There is no reason why this pattern should repeat itself but, if I were a member of a major party, I would be a little concerned. I would be wondering how the process of selecting party candidates for elections and the nature of campaigning could be changed to involve a larger local component. This is a complicated issue because it challenges the direction in which the major parties have been moving for the last 20 years, but it is one which needs resolution. If it is not dealt with, the term ‘independent’ could become much more familiar than it is at present. And the role of independent members of parliament in holding the balance of power might become a commonplace. Independents live their political lives on the margin, but it is at the margin where the action is. Whatever its associations, the idea of an independent may be doomed to become increasingly important for our political system.

Question — Have you done any research into the idea that maybe one of the best ways for parties to re-engage the community is to try and source a lot of their staff support from the local community? I’ve often been quite surprised when I’ve met people working for members of parliament, how often the people who work in their office have no attachment at all to the locality from which they have won an election.

Campbell Sharman — This is part of the recruitment pattern for people in major parties. In some ways, the major parties are in a real bind. They are large organisations and they need bright young people to run them, but the career structure—as with most organisations—may have much more to do with how well you please your superiors than with how closely integrated you are into the local community. So the incentives of large parties at the moment are not designed to encourage greater responsiveness to local issues.

Question — I am worried about the corruption of independents. Senator Mal Colston allowed John Howard to sell part of Telstra because John Howard looked after him. Mal Colston should have died but he’s still alive and well, and he and his sons are millionaires. That says corruption to me. Independents appear to look after themselves, not the country or the community.

Campbell Sharman — I lived in Tasmania for five years, so I know about independents. There are a number of points on this issue. The first one is, if you hold the balance of power, you have no power unless you have at least half the Senate with you. So anything Senator Colston may or may not have done he did with the help of someone else.

Secondly, using your brokerage power to gain benefits for your state or your special interests in the community occurs all the time, but usually it occurs in private, because the people with the most to gain from government activity lobby the bureaucracy or the minister. So when this occurs in the Senate—say when Senator Harradine uses his position to help pave Tasmania over with asphalt or whatever he thinks is a good idea—then this is simply the kind of operation which is visible and open, and he has to defend it. Whereas most of the activities which are hidden away in government lobbying are, of course, invisible.

The third point is that, if you take away political parties, you leave to the representatives the question of framing policy. Some people believe that you need only two parties, and that the only choice you need to make is at election time. Then you let one of the parties rip for three years and then hold them to account at the next election. The whole point of a representative institution is that you have a running check on the system, so that if you believe that parliament has a role in scrutinising government activity you need to fill it with people who are not part of the government. And as far as I’m concerned, it doesn’t matter who they are as long as they are not part of the government—because only those people are going to ask awkward questions, and awkward questions are the only ones worth asking.

Question — I was interested in your link between small electorates and support for independents. Most of the states in Australia have been through fairly extensive periods of electoral malapportionment—certainly Queensland, Western Australia and South Australia have. Has there been any research done, or is there any evidence to suggest that, in those electorates which due to malapportionment were smaller than the average, there was higher than average support for independents—which would tend to support your hypothesis?

Campbell Sharman — We’re dealing with small numbers here. There is another reason why the major parties are in a bind. Supposing the major parties do increase their sensitivity to local issues, and one of the effects of malapportionment or very small rural districts is that the major party local members there are very sensitive to local issues. The parties are afraid to do anything about these members even if they behave in a non-party way or if they flout party activity, because they know the local members can run as independents. Their threat is ‘well, if you don’t listen to me, or do x and y, I might run as an independent’. Of course that has happened in Western Australia—Larry Graham did just that—and I suspect it occurs in other states, where there are relatively well-entrenched major party members who are mavericks. That’s why Graeme Campbell stayed for long as he did, because the Labor Party quite rightly assessed that it was a maverick electoral district, so why not have a maverick inside the tent?

Question — During your talk, one of the things that intrigued me was a consideration that makes the structure of Australian politics very different from politics in most other countries, and that is the existence in this country—and almost nowhere else—of compulsory voting. I wondered whether that factors into any of the points that you’ve made today? I have in mind, for example, that in Queensland three or four years ago in an election for the state lower house, a large number of Pauline Hanson’s party were returned. Now they weren’t independents, they were members of a party, but nonetheless it was considered that their votes reflected dissatisfaction with the major parties. In particular, analyses that were done here at the ANU seemed to demonstrate that a lot of their support came from disgruntled Nationals—which stands to reason. If the election of independents often flows from the same consideration, I wonder whether the propensity we have in this country for forcing people to vote bears on the question that you have just been addressing. There are a number of intriguing questions here, particularly the Tasmanian example, which I find interesting.

Campbell Sharman — The book I referred to by David Solomon makes that point, and argues that the informal vote dropped significantly in the three electoral districts that elected independents in the 2001 election. In effect, he is saying that some of the informal vote is disgruntlement, because voters feel that no matter who they vote for, they’re going to elect a politician. I think in Andren’s seat informal voting is something like one-and-a-half percent, a very small informal vote. But conventional wisdom is that compulsory voting by itself doesn’t have much effect—when Colin Hughes looked at the introduction of compulsory voting he didn’t find too much difference in the outcome. But if you are dealing with very small margins and the fact that there may be more dissatisfaction with the system now than there was—and the fact that it is not even ‘optional preferential’, it is ‘compulsory preferential’—then maybe the more the system is compulsory, the more independents will benefit. It’s an interesting thought, but I have no evidence for it.

Question — I would like to draw your attention to the fact that the Labor Party in Western Australia is making a very big run to eliminate a number of rural and mining areas. Do you think that if that change is successful, in those electorates which will be eliminated—even though those areas will still have to have representation—will that representation be more likely to be independent than previously?

Campbell Sharman — One of the points of my lecture was that the major parties have done a pretty good job up to reasonably recently in accommodating these problems. And as I just mentioned, most parties outside metropolitan areas know that if they are going to be successful they probably have to have someone who is well known in the area. Now, if you make rural electoral districts in Western Australia larger, then you are going to break down that community linkage and therefore you would expect there to be fewer independents. Indeed, one of the problems with the system is that if the electoral districts get too big, you lose regional identity. I was involved in a commission that looked at trying to getting rid of this. We realised we had to increase the size of parliament, otherwise the Pilbara would be linked in with the Gascoigne and you would get mining and pastoral people all voting for the same person—which, if you’ve got some sense of community representation, is not very sensible. But of course, the base for independents at the moment is not in the country, it’s in the urban areas. The two people I mentioned, Phil Pendal and Liz Constable, are very firmly ensconced in metropolitan—normally liberal—electoral districts. And to that extent, if there is a redistribution on more equal sized electoral districts, their electoral districts will get smaller, so there may be more urban independents even if there is a lesser propensity to elect rural ones.

* This paper was presented as a lecture in the Department of the Senate Occasional Lecture Series at Parliament House on 17 May 2002.

[1] All the data used in this paper are taken from the Australian Government and Politics database held at the Political Science Department, University of Western Australia. Much of the information in the database is available on the web at: www.elections.uwa.edu.au

[2] For a study of some of the earliest such groupings, see P. Loveday and A.W. Martin, Parliament, Factions and Parties (1966).

[3] Sydney, Harper Collins, 2002.

[4] Scott Bennett, ‘The Decline in Support for Australian Major Parties and the Prospect of Minority Government’, Parliamentary Library Research Paper no. 10, 1998–99.

[5] Campbell Sharman, Graham Smith and Jeremy Moon, ‘The party system and change of regime; the structure of partisan choice in Tasmania and Western Australia’, Australian Journal of Political Science, vol. 26, no. 3, November 1991, pp. 409–428.

[6] Bruce Stone, ‘Australian Bicameralism: Potential and Performance in the State Upper Houses’, Senate Occasional Lecture, Parliament House, Canberra, 8 November 2002.

[7] Campbell Sharman, ‘The representation of small parties and independents in the Senate’, Australian Journal of Political Science, vol. 34, no. 3, November 1999, pp. 353–361.

Prev | Contents | Next

Back to top