Papers on Parliament No. 55

February 2011

Prev | Contents | Next

Introduction

The 1979 competition for the design of Australia’s new Parliament House followed decades of political consternation on the character and site of what was to become, arguably, the most symbolically important building in Australia. A project of this scale was rare and the competition was much anticipated by the architectural community before its announcement in April. At the close of the first stage of the competition 329 entries had been received with 131 from international architects.[1] The number of overseas entrants was encouraging given the competition restriction that entrants must be registered as an architect within Australia by the date of submission and pointed to the international interest in the project.[2] At the end of the first stage 10 prize winners were announced from which five were selected to prepare a submission for the second stage. On 26 June 1980 Mitchell/Giurgola and Thorp were announced as the winning architects.

In reviewing the architectural competition one needs to understand the historic background to the decision regarding symbolism and location of a permanent parliament house. A home for federal parliament was integral to the establishment of the national capital at Canberra in 1911 and became a perennial topic for consideration by governments since the ill-advised decision to construct a provisional Parliament House in 1923. This historic context will form the basis of the first section of this paper which will look at the physical and cultural issues that fashioned the political framework for the competition. The second part of the paper will analyse how the political agendas were incorporated as explicit and implicit requirements of the competition brief. The paper will also look at what entries attracted the interest of the judges and the criteria used by them to determine the ultimate winner.

Political sensitivities: site, symbolism and the Griffins’ legacy

The process for selecting an appropriate site for a new and permanent Parliament House (NPH) was complex, lengthy and involved arguments over a number of decades on the merits of a range of potential locations within the parliamentary triangle. The final location would need to balance the history and status of the Griffin plan, the ambitions of parliamentarians and the sensitivities of a wary Australian public.

Walter Burley and Marion Mahoney Griffin won an international design competition for the new federal capital in 1912. Within this plan for Canberra they designated the site of Capital Hill as the focus at the apex of the urban design characterised by triangular geometry. The Griffins intended that Capital Hill would host an open public structure and not the legislative functions of government that were to be located down on the river plains to the north in what is now called the parliamentary triangle. The axes of roads and landforms within the Griffins’ plan anointed Capital Hill with an urban power similar to that of the Palace of Versailles but in the case of Canberra it was the public who were to have symbolic ownership of the site.

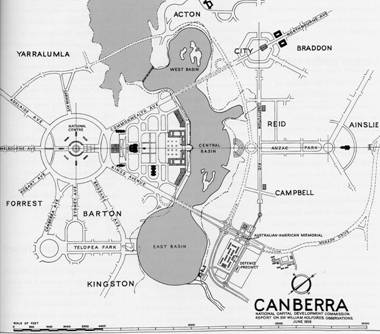

Figure 1: 1913 plan of the Griffins’ scheme with Capital Hill within the circular road in the centre of image, nla.map-gmod30, National Library of Australia.

The Griffins’ architectural vision for Capital Hill was for a stepped pyramidal roofed structure called the ‘Capitol’. This was intended to be the prime building of the new city that would house ‘popular assembly and festivity rather than deliberation and counsel’; a monument to the new federation. The 1912 report by the Griffins that accompanied the competition entry made reference to Parliament House being situated on a small rise called Camp Hill within the river plain below.[3]

The Griffins’ intentions were unravelled with the government decision to construct the provisional Parliament House (PPH) in 1923 at the foot of the modest Camp Hill where according to the Griffin plan the permanent parliament was to be sited. As may be expected the decision to construct the PPH in this location prompted concern and as early as 1923 planners saw problems with the decision. At issue was whether the construction of this ‘temporary’ house would negate the potential of the permanent site.[4]

In light of the interference to the proposed site for Parliament caused by the location of the provisional building, submissions were sought by government from planning bodies and interested experts on relocating the site for the permanent Parliament House. These 1923 submissions were split between locating Parliament on Capital Hill and retaining the original location of Camp Hill. Reasons were offered to support each site, the most telling being that it was symbolically inappropriate to place Parliament in such a prominent location as Capital Hill. Typical of this stand was that of Senator Gardiner who argued that Capital Hill would visually require a monumental structure and he believed the utilitarian function of a parliament building should not provide the massive form necessary.[5] Considerations on a suitable site continued after the Second World War and by the 1950s political support was foundfor Capital Hill.[6] But while it appeared that the site selection of Capital Hill had political backing the saga was not complete.

The Commonwealth Government commissioned a report on the development of Canberra from Sir William Holford, a town planner from the United Kingdom, which was tabled in Parliament in May 1958.[7] In this report Holford concluded that NPH should be sited at a lake-front location at the north edge of the river plain below Capital Hill. Holford conceded that Capital Hill was the ‘generally preferred location’ but again expressed the opinion that symbolically it would be out of place. The houses of Parliament, in Holford’s opinion, should be modelled on an active democratic forum and not a hilltop monument.

These recommendations were quickly endorsed by the newly created National Capital Development Commission (NCDC), the establishment of which was also a Holford recommendation, and the government of the day.[8] This decision appeared to have accepted the political opinion that Capital Hill was too prominent a landform on which to place the Parliament of Australia as it may infer an unacceptable dominance over the public.

Figure 2: Post Holford plan of Canberra with Parliament House located on the edge of the lake and a ‘National Centre’ located on Capital Hill

Holford remained involved and continued to provide advice on aspects of Canberra’s planning and the location of NPH, the tone of which reflected the unease previously felt by some for the Capital Hill site. In 1963 he again discussed the attractiveness of Capital Hill but stressed that the scale of building required for Parliament may prove to be an architectural embarrassment, a point that played upon the fears of politicians. This same report evoked the Griffins’ intentions to support the inappropriateness of the Capital Hill site, although it dismissed the Griffin location in favouring the lakeside site.[9] The NCDC reaffirmed the lakeside decision and prepared development strategies of the parliamentary triangle based on this location.[10]

Although endorsed as the site by both the government and the NCDC the lakeside site did not have general support from politicians. In 1968 a motion to confirm the lakeside site, and supported by the leaders of both sides of Parliament, was put to a free vote of members of Parliament. The motion was defeated and the NCDC was forced to reconsider the options of Camp and Capital hills. In the absence of a ‘lakeside’ option the NCDC favoured Camp Hill describing a Capital Hill parliament as being potentially dominant and separated from the other components of government. Once again a majority of politicians disagreed and a vote of both houses of Parliament in May 1969 favoured the prominence of Capital Hill although the Prime Minister John Gorton overrode the decision and informed the NCDC that the lakeside site remained the government’s decision. A change of government and Commissioner for the NCDC (Tony Powell) again led to a vote in Parliament regarding the site and, as before, a combined vote in 1974 of both houses led to a majority for Capital Hill and the site was finally established by an Act of Parliament.[11]

This decision did not end political unease at the positioning of a new and expensive parliament building on the most prominent location in Canberra with a newly elected government in 1975 having little enthusiasm for the project. Ultimately the matter was referred to Parliament for another joint party vote which clearly supported an immediate start on a new parliament house and with some reluctance the government agreed to proceed.[12] Commentators voiced concerns of the public that the executive of government may have shared. The Bulletin, in an article provocatively titled ‘A House on the Hill for our MPs’, presented some of the salient political sensitivities:

Successive governments have always feared giving the go-ahead to such an enormous undertaking because of possible electoral backlash ... In 1958 the then member for the ACT, Labor’s Jim Fraser, agreed with Menzies [on the lakeside site] and said there was something degrading about people having to crawl up a hill to see a politician.[13]

A newspaper editorial also offered a caution:

We [The Age] agree with the decision [to proceed] and hope that most Australians will resist the temptation to mock the project as a monument to political self-interest, self importance and extravagance.[14]

Contrary to this entreaty, a cartoon by Moir only two weeks after this editorial presented a contrary view that the project was an expensive undertaking for the benefit of politicians.[15]

Political context: lessons of the Sydney Opera House competition

Preparations for the competition for NPH followed the recent 1972 opening of the Sydney Opera House. This world heritage listed building began as a design competition. As a major public building in the most prominent location in Sydney it became embroiled in a range of controversies and political machinations and as such it provided political lessons for the planning of the competition for NPH.

The winning scheme by Jørn Utzon was announced in late January 1957 but proved to be difficult to build using the technologies of the day and costs and time for construction extended well beyond expectations. As it was a New South Wales government project, funded partially through lotteries, there was a great deal of political exposure to public concerns regarding propriety and prudence. The outcomes are well documented with political interference and the ultimate downgrading and eventual departure of the architect Jørn Utzon with associated hue and cry from various sectors of the public.[16] The political problems with the design and construction of the Sydney Opera House stemmed from the spectacular but unresolved form of the original design entry. The nebulous nature of the original scheme required radical innovations in construction techniques. Also remarkable was that the judges chose (albeit through an anonymous process) a scheme designed by a small firm headed by an architect without experience with large-scale projects.[17]

There was political resolve that the controversies that dogged the Sydney Opera House would not be revisited with NPH. As these problems were related to the difficulty of construction then it would have been considered politically expedient for the ultimate winner of NPH to comply with a number of conditions to prevent a similar outcome. These were that the scheme would not be reliant on new technologies and could be constructed within the tight time frame of eight years.[18] Secondly the winning architects must have a demonstrable capacity to undertake a project of such a scale.

Tracing the political in the competition processes

Within a few months of the commitment for the site for NPH[19] the Parliament House Construction Authority had been established, the competition brief completed and an international competition launched in April 1979. Within the framing of the competition brief and conditions we can see the response to the politically sensitive contexts of site selection, vexed symbolism and the lessons gleaned from the Sydney Opera House.

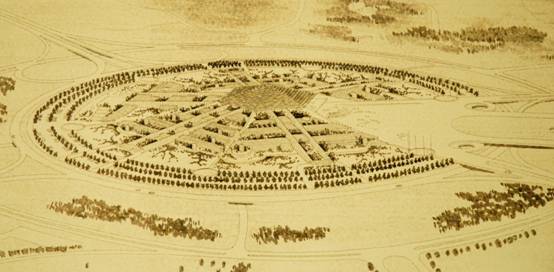

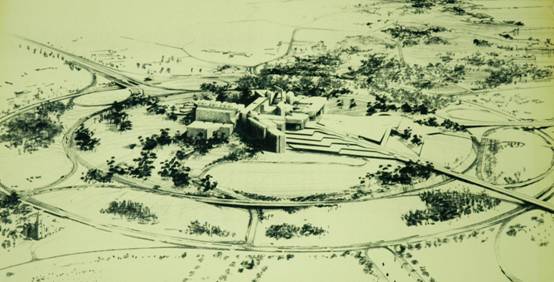

The first indications of these concerns can be seen in how the expectations for the competition outcome were pre-empted. In 1977 the NCDC staged an exhibition to illustrate the way forward for the development of Canberra and included impressions of a new parliament house on Capital Hill. A local architect, Bert Read, was commissioned to create an indication of how a NPH might appear for the sake of promoting development strategies. The result was a cone-shaped design that spread down the hill creating a new built topography that mirrored the existing hill. It had a large flag pole at its centre that corresponded to the apex of the parliamentary triangle and large-scale angled walls that acknowledged the axes of the main diagonal approaches to the site. This scheme not only was on public display for some weeks but was also chosen by the NCDC to grace the cover and interior of the published reports from the Joint Standing Committee on the New and Permanent Parliament House.[20]

Its initial and continued use implied an acceptable approach in response to the architectural and political problems of the site and symbolism. The cone reference to the hill upon which it was placed was to be a common theme in the entries and had resonances with the final winning scheme. Many local architects, who had entered the competition, would have been aware of the scheme which contributed to the political background noise to the competition, a background that was reiterated directly in the competition brief.

Figure 3: The NCDC hypothetical scheme for NPH on Capital Hill. Reproduced with permission from Bert Read.

The comprehensive competition brief included requirements for all aspects of the building including its symbolism. The section on symbolism contained references to the expression of the building which went directly to the heart of the political sensitivity of avoiding grandiose solutions.

The brief called for the design to be a ‘major national symbol’ along the lines of both Westminster in London and the Washington Capitol building. It chose these two examples so that it could distinguish between their architectural expressions. The Capitol building is described as being massive and monumental while Westminster is described as informal and romantic. Canberra’s provisional Parliament House is also described in this section as being less powerful compared to the other two examples while having its own grace and simplicity. The aspects formed the basis of a rhetorical question regarding symbolic expression:

Competitors should consciously evaluate these factors during the design process. They should question whether it is appropriate that a building of the late 20th century use language of bygone eras. What would be the connotations—in the mind of the visitor—of a building with monumental scale, sited on a hill? Does significance mean bigness?[21]

Much appears to have been made as to the impression this building will have on those who visit. It is a public building of which monumentality has no place. The formality of the project was also questioned as the brief discouraged symmetry at the expense of function:

The requirements are not symmetrical ... Symmetry cannot be obtained at the expense of functional efficiency.

Similarly the design should accommodate change as posed in the brief:

Does the nature of the requirements imply an acknowledgement of the forces of growth and change?[22]

The assessors’ report at the completion of the competition described four general criteria against which the entries were judged.[23] Those criteria that applied directly to the design approach and expression were that the design must respond in a sensitive manner to both the natural environment and the Griffins’ concept of the most significant national building being at the apex of the parliamentary triangle. The design was to symbolise the unique national qualities, attributes, attitudes, aspirations and achievements of Australia. This alliterated phrase was looking for an architectural interpretation of an Australian psyche that was not known for its respect of authority or its symbols. Both required the successful scheme to engage with the context of the site, the Griffins’ intent and the nuances of the political context.

As previously noted, this competition occurred only seven years after the completion of the Sydney Opera House and the subsequent problems associated with the project were thought by the NPH organisers to have been partly a function of the modest size of the winning firm. Jørn Utzon ran a small-sized practice in Copenhagen. In what appeared to be a strategy to avoid a repeat of such problems, a complex and extensive brief outlining all functional requirements and adjacencies ensured that only the most dedicated of entrants would be able to resolve the planning issues. To address these detailed brief requirements entailed access to considerable resources that may have been beyond many small firms. Similarly the competition entry requirements of 10 large-format boards included photos of a model of the scheme within the site, which also favoured well-resourced architectural firms. The competition jury selected 10 finalists at the end of the first stage through their anonymous submissions. Of these 10, all would be subject to what was described as a ‘critical review’ which required the entrants to demonstrate that they had the resources and capacity for such a major undertaking.[24] From the 10 finalists, five were invited to the second stage. At the point of determining the 10 finalists anonymity was discarded with the assessors knowing the identity of all. The second stage invitees were given a sum of money to assist in preparing the next submission which entailed detailed resolution of plans and extensive and elaborate models. The entrants were expected to perform at an advanced design level to enable the organisers to have confidence that the winner had the expertise and capacity to see the design of the project through.

The jury deliberations: spots before their eyes

The jury was headed by Sir John Overall, a former chair of the NCDC, who invited the expatriate architect John Andrews to be an assessor for the forthcoming competition. Andrews provided Overall with a suggestion for an international member for the jury. Andrews, an avowed modernist at the time,[25] recommended another prominent modernist, the New York architect I.M. Pei, and both subsequently became the architectural experts on the assessment panel. Other members of the panel were Senator Gareth Evans and Barry Simon MP, representing both houses of Parliament, and Len Stevens, Professor of Engineering at the University of Melbourne, who was appointed to look to the buildability of the schemes under consideration. Paul Reid from the NCDC acted as competition adviser.

Spotted schemes

The five schemes that were selected to advance to the second stage reflected a range of design responses to what was a comprehensive and challenging brief. But the schemes under serious consideration by the panel were wider in the scope of architectural themes than those singled out as potential winners. During the judging process a system of coloured spots was used by panel members to indicate interest in a particular entry. Coloured spots remain on the drawings and reports of a significant number of entries as an indication of the panel’s interest in the schemes.

This contention is supported by the recollection of panel members[26] that there was a direct correlation between spotted entries and the 10 top prize winners.[27] There are a range of colours remaining on this group of schemes. Those chosen for the second stage tended to have red spots with the remaining prize winners having blue spots. The other schemes have blue or brown spots on the drawings, and/or blue or green spots on reports.

In total 40 schemes were marked and an analysis of the schemes that attracted coloured spots provides an overview of architectural approaches of interest to the judges. These 40 schemes included the subsets of 10 prize winners, the selected five second stage entries and ultimately the winning scheme of Mitchell/Giurgola and Thorp. The brief required entrants to respond to the criteria of the Griffins’ plan, context, buildability, program and symbolism. All criteria played a part in the jury’s considerations and the schemes selected were those that responded to all or some of these requirements including specific pronouncements made within the brief regarding the building’s image.[28]

First choice: topographical or imposing?

The brief direction on monumentality posed a rhetorical question:

What would be the connotations—in the mind of the visitor—of a building with monumental scale, sited on a hill? Does significance mean bigness?[29]

In response the selected schemes generally fell into two groups: topographical, where the scheme reflected the rising character of the hill; and imposing, where the scheme placed building forms on the hill. A topographical approach, where the scheme would reflect the hill, may aid in reflecting physical context and reducing monumentality. An imposed building form on the hill required other techniques to dilute monumentality. The spotted schemes demonstrate a range of approaches.

Topographical

The topographical schemes included those that proposed stepped or sloping elements that rose up to an apex. This can be seen in the entries of Synman Justin Bialek (008), Bickerdike (045) and Daltas (145)[30] through to schemes that presented a design that alluded to an abstracted hill. As an example of the latter, the scheme of Staughton (080)[31] presented a low hexagonal cone covering the apex and slopes of Capital Hill (figure 4). Apart from the large forecourt that addressed the land axis it was designed to present an even rise from all view points as one would expect from a gentle hill. This approach accepts the priority of the landscape within the charged context of the Griffins’ vision with a design that is civic in scale but secondary to the geography.

Figure 4: P.S. Staughton, P.S. Staughton and P.N. Pass (080 Vic.), National Archives of Australia, A8104, 80.

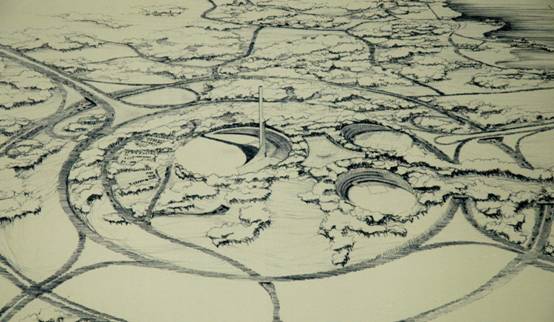

Rather than design a building that enhanced the existing topography, the design of the ultimate winner Mitchell/Giurgola and Thorp (177)[32] replaced the top of Capital Hill with a building that mirrored the existing topography. Access to the new apex of the artificial hill would remain available to the public in an overt gesture on the nature of democracy and as a memorial to the lost natural hill. But even this approach to topographical retention was not the most extreme among the spotted entries. The project submitted by McKenna and Cheeseman (063)[33] placed the building substantially underground making the parliament building subservient to the existing terrain with a large-scale mast as a marker for both the building and, equally important, the climax of the Griffin geometry. It shared with the Giurgola project the concept that the hill would remain physically and visually available to the public.

These topographical approaches offered design responses that were anti-monumental with the McKenna and Cheeseman scheme being not only anti-monumental but anti-building (figure 5). That it attracted serious consideration by the assessors reflected the real concern embodied in the brief that the design must not physically or symbolically dominate the context.

Figure 5: A.T. McKenna & R.D. Cheeseman (063 SA), National Archives of Australia, A8104, 63

Imposing

The converse of this topographical approach was one that imposed buildings onto the hill. Given the discussion within the brief regarding monumentality, the inclusion of schemes that employed this approach bears some analysis as to a finer grained definition of monumentality that was problematic to the panel of judges.

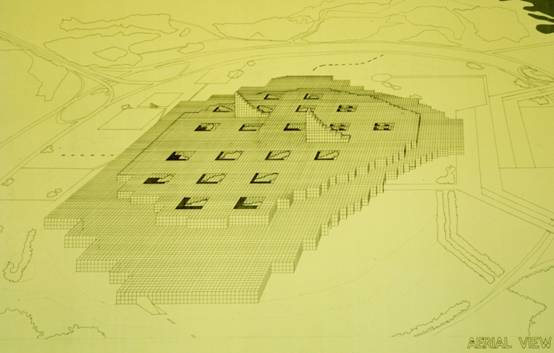

Imposing—organic

One approach to imposing a form onto Capital Hill without representing monumentality was to treat the building as an organism with an expression that reflected the expectation of growth as outlined in the brief. The schemes by Daryl Jackson (136), G.W. Jones (190) and Baird Cuthbert Mitchell (252)[34] demonstrated systems of planning that encouraged expansion through matrices or the growth of repetitive geometric elements. The buildings proposed had dynamic boundaries and avoided formalism and symmetry. A further development of this expression of growth was seen by the Stephenson and Turner (233)[35] project whose scheme included a programmatically driven arrangement of hexagonal forms of various scales. This scheme incorporated a large central split pyramidal form that exuded an expressionist quality. Such sculptural elements were all but extinguished in the scheme submitted by Karack (241)[36] who produced a design that owed much to the non-stop city of Archizoom and Superstudio’s ‘Il Monumento Continuo’ of 1969. It presented an indeterminate form of fine grids that convey an impression that they could expand infinitely. The organic examples gave literal expression to the directive from the brief that forces of growth be acknowledged while reducing the building to a system (figure 6).

Figure 6: J.D.N. Karack (241 UK), National Archives of Australia, A8104, 241

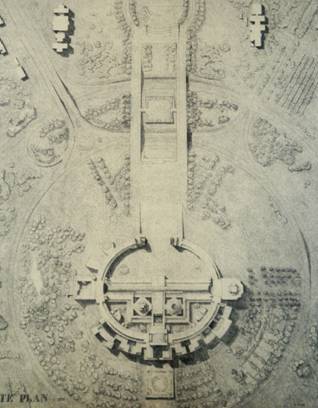

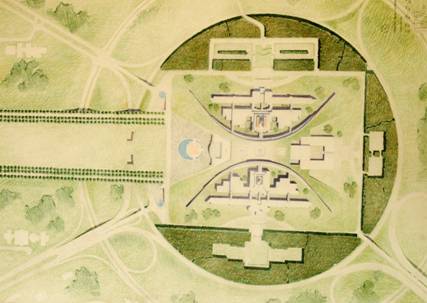

Imposing—circular

Another design theme popular among the general entries and well represented within the spotted schemes was to draw from the circular geometry of Capital Hill. The Ancher, Mortlock and Woolley (090) scheme and the entry from T.S.R. Kong (260)[37] both had circular forms with geometric forms enclosed. This follows the modernist technique of formal hierarchy with the main public functions of government housed in abstract platonic forms surrounded by the administration of parliament. The circular geometry was also used in the schemes by Hurburgh of Bates Smart and McCutcheon (176), J.D. Fischer (265) and Lyon (179). In these cases the circles were less complete than previous examples and integrated radial dynamism within the planning. These approaches generally pushed the building form away from the centre of the hill and even when occupying the apex did so with forms that were either recognisably abstract modern, asymmetrically arranged or both.

Figure 7: I. Collins, Anderson and Collins (116 NSW), National Archives of Australia, A8104, 116

Imposing—horseshoe

A series of projects within the select group incorporated circular geometry without occupying the top of the hill and open to the Griffins’ land axis. These horseshoe plans by Collins (116) (figure 7), Waite (201) and Neilsen (291)[38] represented another popular theme within the general entries. This approach to the site retained the apex for public access and formed the building around this space in the manner of an arena. The character of this approach prioritised the public role in government by making the key space not an internal function but a grandiose forecourt in the mode of James Stirling’s project for the Derby Civic Centre (1970). In these examples urban scale is achieved not through built form but the public offering.

Asymmetry

While the above examples tackled the issue of monumentality through various strategies of distributing formal mass it is apparent that scale in itself was not the only concern, rather the expression of scale was important. In this light the caution contained within the brief warning entrants not to promote symmetry at the expense of program was taken to heart by many entries within the select spotted group. These schemes demonstrated the struggle between asymmetric program and the civic importance of the building. The latter, coupled with the powerful geometry of the site and the urban mirror line of the land axis, could encourage a symmetrical solution empowered by the tradition of the typology of civic architecture and the Griffins’ urban legacy.

Of the 40 selected schemes 10 employed asymmetry as an expressive device. This was exemplified by the entries of Williams, Boag and Szekeres (073), Seidler (075), Waclawek and Wojtowicz (030) and Bates Smart and McCutcheon (057).[39] This approach was grounded in the modernist ethos that asymmetry promoted the functions of the building and as the driving dynamic for the architectural expression. This was particularly clear in the entry of Edwards, Madigan, Torzillo and Briggs (234) which was selected for the second stage.[40] This project drew upon geometries unrelated to the site to produce a scheme that challenged the symmetrical urban framework. This entry, as with the firm’s projects for the High Court and National Gallery within the parliamentary triangle saw the architectural response as a counterpoint to the powerful geometric overlay of Canberra. Madigan’s attitude to the symmetry of the parliamentary triangle was expressed in his comment that the design of his two buildings ‘reacted strongly against the asphyxiating order of conformity and responded to the halcyon optimistic spirit of the early 70s’.[41] This project should be considered a monumental imposition on Capital Hill but its modernist dynamic packaged the scale into a form acceptable to the assessors (figure 8). Their acceptance of the scheme extended to it being invited to progress into the second stage of the competition.

Figure 8: Colin F. Madigan, Edwards Madigan Torzillo and Briggs International Pty Ltd (234 NSW), National Archives of Australia, A8104, 234

Programmatic asymmetry

While expressive asymmetry was employed in some of the selected schemes, others took a more circumspect approach to what appeared to be competing pressures of function and civic presence. These developed a form of programmatic asymmetry where the overall approach was a symmetrical response with asymmetrical nuances. Of the 40 selected entries 15 demonstrated a symmetrical frame or spine upon which asymmetrical elements were attached. This was exemplified in the projects of Bickerdike (045), Addison-Kershaw (061) and Webster and Bray (276). The stage one entry of Mitchell/Giurgola and Thorp (177) also followed this approach. In what, at first glance, appeared to be an emphatic symmetrical design, the secondary buildings that serve the functions of government are balanced but asymmetrically expressed either side of the land axis.

Symmetry

The selection of entries did not exclude symmetrical entries and eight projects demonstrated this approach. But of these schemes only two could be considered to have treated the symmetry in conjunction with elements that could be considered monumental in scale.[42] The other schemes were designed to ameliorate aspects of monumentality. Of particular interest is the entry by Denton Corker Marshall (139). This project was an interesting inclusion on a number of issues, not the least being that it was the only completely symmetrical scheme to progress to the second stage. The plan of the building itself resembled a neoclassical arrangement, a historical reference that seems at odds with the intonations of the brief and the attitude of the judges. But, similarly to the Giurgola scheme, the Beaux Arts planning was abstracted within contemporary, or certainly non-historical, expression. The potential monumentality of the Denton Corker Marshall arrangement was diluted by the use of a three-dimensional Cartesian grid system that encased the design in a transparent network on a range of scales. The building placed in the context of the extended site works can also be appreciated as potentially expanding within the implied Cartesian universe as indicated in the super-grid on the site plan. Although it shared aspects of postmodern appreciation of classical precedence it presented it within a form that eschewed classical solidity (figure 9).

The acceptance of these symmetrical schemes suggest that the veiled warnings in the brief were aimed at a form of symmetry that was aligned with historical monumentality and that it was not a hurdle in its own right.

Figure 9: Denton Corker Marshall (139 Vic.), National Archives of Australia, A8104, 139

Crossing the land axis

Another significant theme within the selected projects was the site-planning approach that set the building across the land axis. The four entries by Leech (127), Venturi (207), Borg and Zly (147) and McIntyre (246)[43] all have long rectangular forms that sit across the site. This response to the geometry of the parliamentary triangle is to place a barrier across the urban sight lines in what would appear as significant visual levees. These schemes are something of an oddity within the overall selection as they are, at first glance, monumental impositions upon the Capital Hill that counter the geometry of the context. But they have characteristics that address the issues of scale and bulk. The schemes of Borg and Zly (147) and McIntyre (246) consist of a series of forms set within open hurdles that bridge from one side of the site to the other. This approach, redolent of the mega structures of the Italian Rationalists and Vittorio Gregotti, treated the built form as a frame for the other elements and allowed the impression of visual penetration. The Leech (127) project does not act as a frame but alleviated the visual bulk by battering the façade of the main form balanced by an asymmetrical positioned smaller form. The Venturi scheme (207) curved the front façade of an asymmetrically located form which also stepped down to the east. The eye would be drawn in toward the central opening along the land axis and deflected away to the sides of the site (figure 10).

Figure 10: Jerry Wayne Carrol, Venturi Rouch Brown & Carrol (207 US), National Archives of Australia, A8104, 207

It has been argued in this paper that the spotted selection of schemes represent a range of interpretations of the symbolic parameters contained within the brief that were acceptable to the assessors. There is a broad scope of themes that by virtue of being within this group were worthy of consideration and as a group they can tell a story as to the collective thinking of the judging panel.

Unspotted themes

While the selected schemes portrayed various architectural themes a range of design strategies within the overall body of the entries were not included. A survey of some of the themes that did not make the grade may add further light on the jury considerations.

Given the prescriptions of the brief the assessors were not going to be easily impressed with singular monumental gestures and despite the preponderance of such schemes within the entries none of this ilk were included in the selected grouping. The large scale equilateral triangular form of Robin Gibson (186)[44] was a well resolved example of this type that relied on the power of a single form to contain the parliament. Other schemes with sculpturally expressive monumental gestures were significantly represented within the entries but those as exemplified by the project by Silver Goldberg (240)[45] were also noticeable by their absence from the selection.

Figure 11: Douglas Norwood (195 UK), National Archives of Australia, A8104, 195

A number of themes current in the late 1970s period are not represented. Journals had given substantial coverage to the Centre Pompidou which had recently been completed but this project did not feature as a significant influence within the entire body of submissions. The project by Pierce (002)[46] could be seen to have a passing similarity to one of Piano and Roger’s early proposals[47] but this theme was a rarity. Although the influences of hi-tech were not immediately apparent the parallel influences of Archigram and the Metabolists were found in a significant number of schemes. This genre of late-modern architecture did not feature within the assessors’ selection. It may have been the mega-structure expression of this genre, as demonstrated by the Norwood (195) scheme,[48] which gave the assessors pause (figure 11).

A number of entries departed from conventional geometry and proposed schemes of informal planning, often coupled with organic expression. Within the spotted group, projects were controlled by geometric frameworks and even Madigan’s asymmetrical scheme retained control over the arms of the design that acted as balanced counterpoints to the rectilinear structure of the design. Viewing the relaxed geometries of Corrigan (118) and David Moore (109) as examples of this type, the urban planning owed more to the Acropolis and the hilltop village than the fortified citadel. These typified schemes that eschewed monumentality and the geometry of the precinct through informality but this lack of geometric stricture did not feature within the spotted projects.

Figure 12: S. Korzeniewski (106 NSW), National Archives of Australia, A8104, 106

While circular geometry was a common response to the site and the Griffins’ planning, the geometry of the oval also featured significantly within the general entries. Despite its relative prominence, the selection of spot-worthy schemes did not include an example of this type. One example was the scheme by Korzeniewski (106) that located the public functions of government within half of the oval with the other half as a semi-enclosed formal forecourt. The language is controlled and abstract but the expression draws from Baroque Rome and it may be this connection between the oval geometry and classicism that had a bearing on the exclusion of this genre from the spotted selections (figure 12).

Conclusion—winning scheme

Within the spotted selection 10 projects received prizes and five were promoted to the second stage. The themes within the second stage were the abstract symmetry of Denton Corker Marshall, the topographical approach of Giurgola, the expressive asymmetry of Madigan, the introverted horseshoe of Parsons and Waite and the restrained British rationalism of Bickerdike. Each of these represented distinct themes and offered a sample box of approaches. They also provided a summary of acceptable responses to the questions posed in the brief regarding the suitable architectural expression. The implications of these questions support an architecture that would not dominate the site through monumental scale, forced symmetry and the language of bygone eras. The discussion within the brief on symbolism was a proactive first strike. As the section on symbolism was couched in passive terms and relied on rhetorical questions, a review of the schemes deemed worthy of consideration reveals the range of acceptable architectural manifestations. The spotted schemes belonged to a much broader range of architectural expression and offer a more detailed picture of the assessors’ interpretation of acceptability than that inferred from the second stage participants alone.

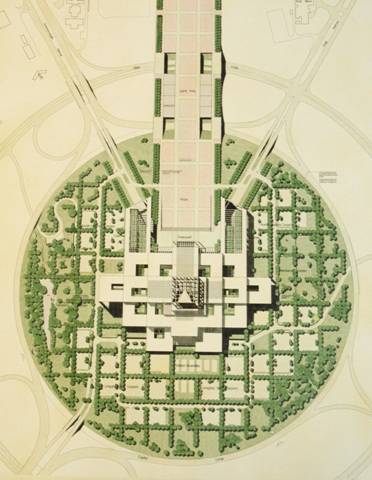

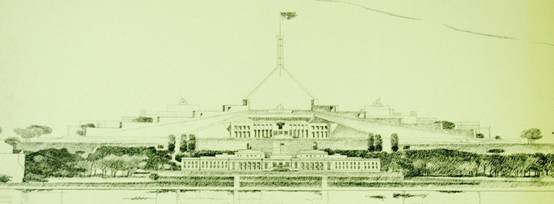

The Mitchell/Giurgola and Thorp (177) scheme was the only design that proposed to replace the top of the hill with a topographically formed building.[49] This responded directly to the expressed concerns of the building dominating the site and looking down upon the public. The low profile of the building sat well within the controversy as to whether a building of this scale should be located on Capital Hill. As a climax to the triangle the vistas to the site sweep over the building in the same manner that the public (and children) could once do.[50] The first stage submission by Mitchell/Giurgola and Thorp had all the salient features of the final scheme but did make a limited gesture to the asymmetry alluded to in the competition brief. The curved walls symmetrically embrace the two houses and associated administration accommodation which was shown as being able to grow in a piecemeal fashion. In the second stage submission these forms were symmetrically designed signalling a greater commitment to the Beaux Arts compositional undercurrents of the scheme.[51] The issue of asymmetry raised in the competition brief was in part to ensure that by eschewing symmetry then classical monumentality may be avoided. The Mitchell/Giurgola and Thorp design offered a low-key image within a symmetrical framework. It was a non-monumental monument.

Figure 13: Elevation, Mitchell/Giurgola and Thorp (177 US), National Archives of Australia, A8104, 177

The competition assessors’ report on the winning scheme touched on this when they claimed that an ‘overpowering building presence’ would be ‘undemocratic’. Instead the expression of the Mitchell/Giurgola and Thorp scheme will be accessible for all, even children who ‘will clamber and play all over its roof’. Presumably the same children ‘will not only be able to climb on the building but draw it easily too’. The lack of pretensions of the scheme would allow its simple imagery to become part of the nation’s lexicon of kitsch icons ‘the obvious boomerang analogy of the curvilinear walls ... may in time become as internationally representative of Australia as the kangaroo’.[52] The entreaty for popular acceptance of a design within the conceptual reach of the general public points to the relief felt from the controlling authorities that the winning scheme avoided ostentation and aloofness and that this may dampen the inevitable public criticism of committing the public purse to one of the largest projects in Australia’s history. The resultant built topography is a political solution of the most exquisite order, the political parameters for which were firmly in place well before the competition was envisaged. Tracing the political management and concoction of the competition processes and brief it is hard to imagine an acceptable alternative to the winning entry. If the complex criteria to win the competition can be visualised as square hole, the Mitchell/Giurgola and Thorp entry offered a square peg as a perfect fit.

Figure 14: Site Plan, Mitchell/Giurgola and Thorp (177 US), National Archives of Australia, A8104, 177

Question — Will you tell me what this architecture that’s been foisted on us is supposed to symbolise?

Andrew Hutson — Well I have spoken briefly about the symbolic expectations of the competition organisers and what we have in this particular design for Parliament House is a symbolism which is supposed to be avoiding monumentality and ostentation. To paraphrase a headline from the 1980s, this building is not meant to look like a ‘palace for politicians’. It was meant to look like working houses of parliament. Whether it does or not is open to interpretation but I can perceive from the competition framework that the organisers wished to avoid an outcome of unnecessary grandeur.

Question — As one of probably a handful of people in the world who has seen the designs, do you think the right design won? Secondly, since this building is based on a 30-year design, do you think it has dated?

Andrew Hutson — I knew someone would ask me whether I thought the judges’ selection of the winner was the right decision or not. I think everyone has their own opinions about architecture, art and fashion and I think anyone will look at all those entries and find something they would prefer as a potential solution. I don’t doubt that for a second. But I do think that the Mitchell/Giurgola and Thorp entry was one of the few solutions that could have won given the way the competition was organised and the context of the political and cultural sensitivities surrounding it. There were very few entries which were able to deal with those pressures in such a proficient and controlled manner. Did I think the right design won? Probably. But did I think it was the only one that could win the competition? Almost definitely.

Now, with regard to fashion—building designs are a testament to the time when they are built and I don’t think the fact that fashions and tastes change is relevant when considering whether a building is good architecture. I think they are statements of when they were built and in a hundred years time they’ll still be examples of that period. I think that all architects can aim for is for their work to be good examples of a style. The idea that architecture can be timeless is an old-fashioned idea. That’s a joke, by the way.

Question — I notice that the tourism authorities tend to play down Parliament House and to attract people to Canberra talk about the vineyards, the sporting facilities, the War Memorial etc but don’t mention Parliament House. What can be done to appreciate Parliament House as a great gift to the nation rather than play it down and ignore it?

Andrew Hutson — I don’t know that I can answer the question about how you might make it more attractive because it should, for anyone coming to Canberra, be one of the most attractive features here and I’d be surprised if tourists didn’t make an effort to come to Parliament House because symbolically it is at the centre of Canberra and there is an air of intrigue about political machinations contained within. You never know whether if you come to Parliament House some of those political situations might spill out onto the foyer or into the forecourt. I think that’s a very attractive feature of Parliament House and I don’t know what else you could do to make it more alluring.

Question — My understanding is that Parliament House is essentially see-through. There is a very narrow window down at the back of the prime minister’s courtyard, it’s a long skinny, pencil-like window and you can look all the way through—in theory—and I always wonder what are you looking through to? What’s behind here and why does that land axis cut Parliament House in half?

Andrew Hutson — To actually see through the building you’d have to go through the Great Hall, and I think through the prime ministerial executive and then to see the slit window through the back there. For all intents and purposes it stops at the forecourt.

Question — When all the doors are open you can actually see through?

Andrew Hutson — You may, yes, but I don’t think it is likely. The other issue is: with what was the land axis supposed to be aligned? The Griffins intended that it would lead to Capital Hill but in their competition scheme the view across the lake shows a mountain behind which actually doesn’t exist to that scale and looked a bit like Mt Fuji. You’ve probably seen it. I think that there was some indication that the axis would line up with that as well as going through Capital Hill. I believe the competition by the Griffins was done without them visiting the site and it was based on topographical maps. I think once they visited the site it was determined that obviously the land axis would logically lead to, and effectively terminate at Capital Hill. In that respect it is not intended to flow through exactly, although that faint possibility is there.

With regard to the idea that you can see through the Parliament, I think that’s also part of a symbolic idea of access and should be seen with the symbolic idea of the public being able to walk over the roof of Parliament House. Initially the idea that you could roll over it—and that children could play on it—was a supposedly democratic theme which was taken up by the assessors and the commentators on the final scheme. To say this is a building which is accessible inside and out is to portray it as a democratic building which is not owned by politicians; it’s owned by the people of Australia. The fact that you can walk over the top of it and in some cases, you can actually see into and perhaps through it was important. The design was promoted as a way of alleviating the idea that it was an exclusive place. Rather it was intended to be seen as inclusive.

Question — A question that is nothing to do with the architecture but that I have found myself wondering yet again is: is it in the wrong place? Fairly recently Senator Bob Brown made the point that if you are coming over Commonwealth Avenue bridge it is very difficult to get here whereas if you look at other parliaments around Australia, let alone around the world, they’re in the city. You can go walking along Macquarie Street in Sydney and there is Parliament House. It’s easy to find down the Salamanca Markets in Hobart and I sometimes have wondered whether or not it isn’t as accessible to people because they can’t walk to it easily.

Andrew Hutson —When there was consideration about changing the site from Camp Hill to Capital Hill there was concern among some politicians that they couldn’t expect the public of Australia to trudge up the hill to visit parliamentarians. So the issue has been in the minds of the planners for a long time and has something to do with the reluctance, I think, to finally bed down where the site for Parliament House would be. Whether they made the right decision again is open to interpretation.

[1] Entries for the competition were to be submitted prior to 31 August 1979, three months following the release of the competition brief on 31 May.

[2] Parliament House Canberra: Conditions for a Two-stage Competition, vol. 1. [Canberra, Parliament House Construction Authority], 1979, p. 11. Answers to entrants questions dated 27 June 1979 confirm that entrants must be registered as architects before the closing date of the first stage.

[3] Walter Burley Griffin as quoted in John W. Rees, Canberra 1912. Melbourne, Melbourne University Press, 1997, p. 144. Also from a written description that accompanied the Griffin competition entry in his Plans and Reports (1912, 1913) contained in Extracts Regarding Permanent Parliament House, miscellaneous material kept at the National Capital Authority library. A 1913 explanatory submission by Griffin added that the Capitol would also house archives and commemorate Australian achievements and would represent the sentimental and spiritual head of the nation.

[4] I use the term ‘temporary’ although the building was referred to as ‘provisional’ to avoid an unsavoury impression that Australia’s parliament would be located in a temporary structure. The term was reportedly coined by Colonel Owen, Director General of Works, who was a member of a three-man departmental board to oversee the design of Canberra. This is discussed in Jenny Hutchison, ‘Housing the Federal Parliament’, Working Papers on Parliament. Canberra, Canberra College of Advanced Education, 1979, p. 84.

[5] Report Together With Minutes of Evidence, Appendices, and Plans Relating to the Proposed Erection of a Provisional Parliament House, Canberra. [Melbourne], Government Printer, 1923, pp. 5–13.

[6] Parliament House, Canberra: Statement on the Case for a Permanent Building. Canberra, Government Printer, 1957, extracts regarding permanent Parliament House, miscellaneous material kept at the National Capital Authority library, Part D.

[7] Sir William Holford, Observations on the Future Development of Canberra ACT. Canberra, Government Printer, 1958, relevant discussion pp. 12–15.

[8] The creation of the NCDC was part of the political power play concerning control over the planning over Canberra. An excellent description of these power struggles between bureaucracies and Parliament with regard to the new Parliament House in the 1970s can be found in James Weirick, ‘Don’t you believe it: critical responses to the new Parliament House’, Transition, Summer/Autumn, 1989, pp. 8–16.

[9] Report to Parliament, Richard Gray, William Holford, December 1963, extracts regarding permanent Parliament House, miscellaneous material kept at the National Capital Authority library, Part F.

[10] National Capital Development Authority, The Siting of the Houses of Parliament. Canberra, NCDA, 1963.

[11] Hutchison, op. cit.

[12] Michael Prain, Sun, 16 November 1978.

[13] Jacqueline Rees, The Bulletin, 5 December 1978, p. 26.

[14] Editorial, The Age, 17 November 1978, p. 11.

[15] Moir, The Bulletin, 5 December 1978.

[16] For a detailed account of the background, competition and construction of the Sydney Opera House I would commend, David Messent, Opera House Act One. Balgowlah, NSW, David Messent Photography, 1997; and Anne Watson (ed.), Building a Masterpiece: The Sydney Opera House. Sydney, Powerhouse Publishing, 2006.

[17] Peter Murray, The Saga of Sydney Opera House. New York, Spoon Press, 2003, p. 12.

[18] The opening for NPH was pre-set for 1988, the bicentenary of White occupation of Australia.

[19] Prime Minister Fraser announced on 22 November 1978 the commitment to the construction of a new parliament house by Australia’s bicentenary of 1988.

[20] The New and Permanent Parliament House, Canberra. First report of the Committee on the New and Permanent Parliament House, Canberra, AGPS, 1977. In this report, prepared with the assistance of the NCDC, an aerial view of the Read scheme graces the cover, while another two views are prominent in the first few pages.

[21] Parliament House Canberra: Competition Brief and Conditions, vol. 1. Canberra, Parliament House Construction Authority, May 1979, p. 15.

[22] Parliament House Canberra: Conditions for a Two-stage Competition, vol. 2, op. cit., 1979, p. 15.

[23] Parliament House Canberra, Assessors Final Report, June 1980, p. 4.

[24] Parliament House Canberra, Competition Brief and Conditions, op. cit., p. 12.

[25] John Andrews, 25 May 2005.

[26] Professor Len Stevens, from interview with author and May Eshraghi, 23 September 2004, Melbourne; John Andrews, 25 May 2005.

[27] Nine out the 10 first stage prize winning schemes had spots on either drawings or reports. The scheme by Brown Daltas has no spots on the drawings. The report for this scheme was logged but cannot be traced.

[28] Professor Len Stevens, from interview with author, 2 June 2004, Melbourne.

[29] Parliament House Canberra, Competition Brief and Conditions, op. cit., p. 15.

[30] Synman Justin & Bialek (008 Vic.); J. Bickerdike: Bickerdike Allen Partners (045 UK); Spero Daltas: Brown Daltas and Associates Inc. (145 USA).

[31] P.S. Staughton, P.S. Staughton and P.N. Pass. (080 Vic.).

[32] R. Thorp: Mitchell/Giurgola and Thorp (177 USA).

[33] A.T. McKenna and R.D. Cheeseman (063 SA).

[34] Daryl Jackson: Daryl Jackson Architects Pty Ltd (136 Vic.); G.W. Jones (190 NSW) and Baird, Cuthbert, Mitchell, Architects (252 Vic.).

[35] M.H. Lindell: Stephenson and Turner (233 Vic.).

[36] J.D.N. Karack (241 UK).

[37] Ancher Mortlock and Woolley Pty Ltd (090 NSW) scheme and the entry from T.S.R. Kong (260 Vic.).

[38] I. Collins Architect: Anderson and Collins (116 NSW); C.H. Waite: Parsons and Waite Architects (201 NSW, Canada) and J. Neilsen: Arkitektfirmaet, H. Gunnlogsson and J. Neilsen (291 Denmark).

[39] Peter Williams, Gary Boag and Julius Szekeres (073 Vic.); Harry Seidler and Associates Pty Ltd (075 NSW); Jakub Waclawek and Andre Wojtowicz (030 Poland) and Bates Smart and McCutcheon Pty Ltd (057 Vic.).

[40] Colin F. Madigan: Edwards Madigan Torzillo and Briggs International Pty Ltd (234 NSW).

[41] Colin Madigan, ‘The city as history, and the Canberra triangle’s part in it’, Walter Burley Griffin Memorial Lecture, 5 October 1983, as cited in Paul Reid, Canberra Following Griffin. Canberra, National Archives of Australia, 2002, p. 299.

[42] Robert Day of Hobbs Winning Leighton and Partners Pty Ltd (081 NSW), R.G. Lyon: Lyon and Lyon (179 Vic.).

[43] Denis Leech, Architect (127 NSW); Jerry Wayne Carrol: Venturi Rauch Brown & Carrol (207 USA); M. Borg, J. Zly Architects (147 Vic.) and R.P. McIntyre: McIntyre McIntyre and Partners Pty Ltd (246 Vic.).

[44] Robin Gibson (186 Qld).

[45] Silver Goldberg and Associates (240 WA).

[46] R.F. Pierce (002 UK).

[47] Centre Pompidou Issue, Architectural Design, vol. 47, no. 2, 1977, p. 103.

[48] Douglas Norwood (195 UK).

[49] Assessor Len Stevens recalls that the Mitchell/Giurgola and Thorp design was the only scheme to take this approach. Interview with A. Hutson, 17 March 2004.

[50] Public access to the roof from the exterior of Parliament House has been prohibited in fear of terrorist attacks. The temporary bollards that bar access are soon to be replaced with permanent fixtures.

[51] Giurgola’s architectural education was at the University of Rome under a Beaux Arts framework and he enjoyed an affiliation with the ‘Philadelphia School’. Robert Stern, New Directions in American Architecture. New York, G. Braziller, 1969; E.B. Mitchell and R. Giurgola, Mitchell/Giurgola Architects. New York, Rizzoli, 1983, pp. 8–13.

[52] Parliament House Canberra, Assessors Final Report, June 1980, p. 9.

Prev | Contents | Next

Back to top