Standing Committees

20 Library

-

A Library Committee, consisting of the President and 6 senators, shall be appointed at the commencement of each Parliament, with power to act during recess, and to confer and sit as a joint committee with a similar committee of the House of Representatives.

-

The committee may consider any matter relating to the provision of library services to senators.

-

The President shall be the chair of the committee.

Amendment history

Adopted: 19 August 1903 as SO 34 (corresponding to paragraph (1))

Amended:

- 2 December 1965, J.427 (to take effect 1 January 1966) (changes in terminology and timing: committee to be appointed at the beginning of each “Parliament” rather than each “Session”)

- 24 August 1994, J.2053 (to take effect 10 October 1994) (President designated as chair in new paragraph (3))

1989 revision: Old SO 34 renumbered as SO 20 and committee functions specified in paragraph (2)

Commentary

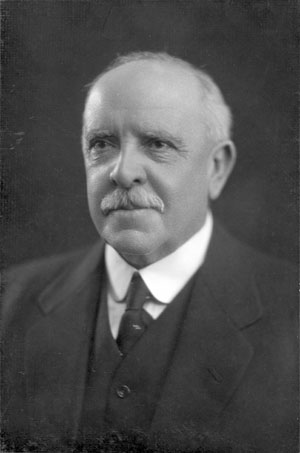

Senator Walter Kingsmill, President of the Senate 1929-32, who insisted that both branches of the legislature be represented equally on joint committees (Source: National Library of Australia)

A Library Committee was established on 6 June 1901, along with House, Printing and Elections and Qualifications committees. Earlier that day the Senate had resolved to adopt the standing orders of the South Australian House of Assembly, with appropriate omissions, pending development of its own.[1] The House of Assembly’s standing orders provided for a Library Committee of the same size as the Senate’s and for the Presiding Officer to be an ex officio member, but no direct line of parentage is drawn between them in any of the surviving records. When the Standing Orders Committee put forward its proposals in October 1901, it noted that the standing orders for the Library Committee and the other domestic committees were based on the procedure already adopted by the Senate.

It was intended that the committee meet jointly with the equivalent House committee and for this reason it was important, according to senators, that it have the same number of members as the equivalent House committee.[2] This issue was the source of tension between the Houses in 1929 because, according to the 1938 MS, the House of Representatives had been in the practice of appointing more than seven members to both its Library Committee and House Committee. When the Senate committees were appointed early in the 12th Parliament, President Kingsmill made statements to the Senate, first in relation to the House Committee and then in relation to the Library Committee, that it would be impossible for him to be a party to a meeting of a Joint Library Committee upon which the two branches of the legislature were not equally represented. Debate on the motion to appoint the Library Committee was adjourned. In the meantime, Prime Minister Scullin moved motions in the House of Representatives to discharge the excess members from the relevant committees of that House. The Senate Library Committee was appointed shortly afterwards.[3]

In his 1938 MS, Edwards included notes on committee powers generally, starting with section 49 of the Constitution, quoting Erskine May (10th edition) on the duty of committees to fulfil, as far as possible, the “duty laid upon them by the House”, and noting that, in the absence of any particular duty laid upon either the Library or House Committee by the Senate, any duties or functions performed by these committees had developed by usage. He quoted the evidence of Sir Robert Garran to the Select Committee on Senate Officials, that Senate committees “have just such powers as the Senate gives them”.[4] None of the standing committees had powers other than as enumerated in paragraph (1) of the current formulation. Nor did the Library Committee (or either the Standing Orders or House Committees) have a “duty statement”. This point was addressed in the 1989 revision when paragraph (2) was added. The purpose of this addition, according to the summary of proposed changes of substance tabled with the first draft of the revision, was to include a statement in general terms of what the committee was intended to do.[5]

Since 1901, the committee had been chaired by the President as a matter of practice. In 1994, following the restructuring of the legislative and general purpose standing committees and the concomitant reallocation of a number of committee chairs to non-government senators in order to more accurately reflect the composition of the Senate, the President was confirmed as the chair of the Library Committee.

The committee functioned exclusively as a joint committee, meeting with its House of Representatives counterpart, until the end of 2005. Consequent on the passage of the Parliamentary Service Amendment Bill 2005 and the appointment of a Parliamentary Librarian pursuant to the amended Parliamentary Service Act 1999, a new Joint Standing Committee on the Parliamentary Library was established by resolution of both Houses, to carry out functions mentioned in the Act and elaborated by the resolution of appointment.[6] When the Senate agreed to the resolution of appointment on 7 December 2005, the unequal number of senators (6) and members (7) on the committee was not remarked upon.

Although the new joint committee effectively superseded the former Library Committees of each House, the members of the Senate committee were not discharged and the standing order was not repealed or suspended. However, the same senators who were members of the Senate committee (other than the President) were appointed as members of the joint committee. Hence forth, members appointed to the joint committee are taken to be appointed as well to the Senate committee of which the President is also an ex officio member.