Phillip Hawkins, Patrick Nykiel

This brief

provides an overview of the key fiscal and economic numbers from the 2017–18

Budget.

The 2017–18 Budget reaffirms a plan by the Australian

Government to return the Budget to balance in the 2020–21 fiscal year and

remain in surplus over the medium term.[1]

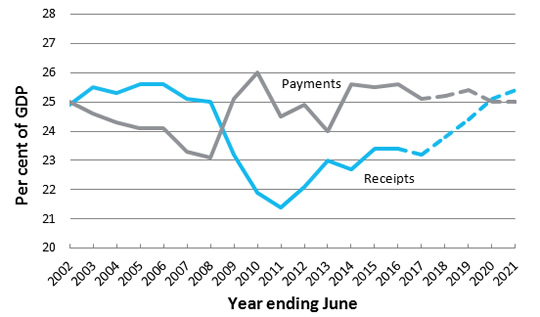

Achieving this surplus depends on closing the gap between

payments and receipts. The Budget papers show that this will predominately be

achieved by increasing receipts (Fig 2). Over the next four years, total Government

receipts are forecast to grow by around 6.7 per cent per annum from 23.8 per

cent of GDP in 2017–18 to 25.5 per cent of GDP in 2020–21. New measures

announced in this Budget are expected to add around $23.0 billion to revenue

over this period.

Over the same period, total payments are expected to grow at

around 4.2 per cent per annum (in nominal terms), declining slightly from 25.2

per cent of GDP in 2017–18 to 25 per cent of GDP in 2020‑21. New measures

announced in this Budget are expected to add $17.4 billion to expenses over the

five years to 2020–21.

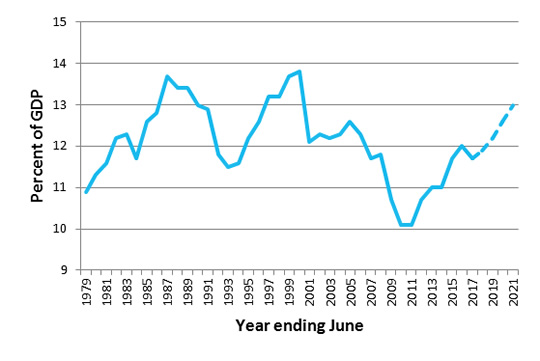

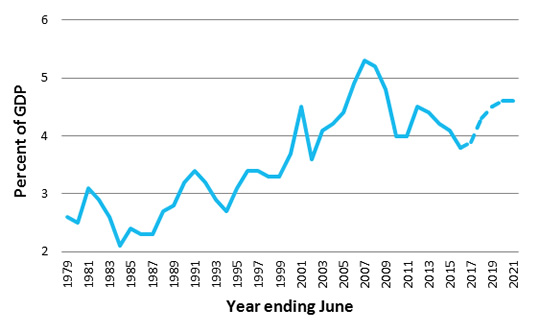

Most of the revenue increases in the budget are related to personal

income taxes,[2] which make up just under

half of all government receipts. These are expected to grow to their highest

level as a share of GDP since 1999–2000 (Fig 4). The growth in personal income

tax is being driven predominately by an increase in the Medicare Levy (which is

estimated to add $8.2 billion to tax revenues over the next four years) and

strong wages growth.[3]

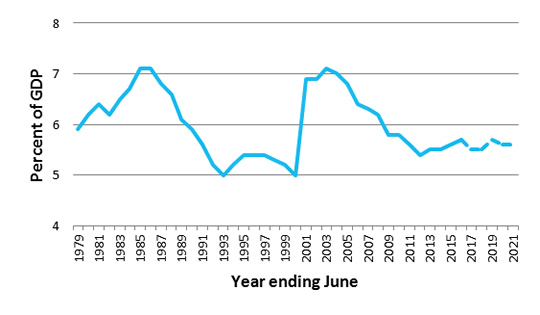

Company tax receipts[4] are also forecast to grow

strongly over the next four years, to their highest level since 2008–09, on the

back of improved corporate profitability and higher than previously forecast

commodity prices (Fig 5).[5]

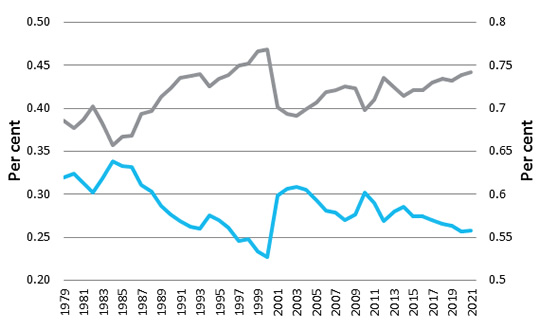

In contrast, sales taxes,[6] excise and customs duties

are not expected to change significantly over the next four years, remaining

around their lowest share of GDP since the GST was introduced in 2000 (Fig 6). As

a result, indirect taxes are expected to fall to their lowest share of total

revenue since the GST was introduced (Fig 7).

Underlying these improved revenue forecasts are improvements

in a number of key macroeconomic parameters. By 2020–21, wages growth is

forecast to increase to its highest annual growth rate since 2010–11 (Fig 14)

and unemployment is expected to fall to its lowest level since 2011–12. Real

GDP growth is expected to improve from 1.75 per cent in 2016–17 to 3 per cent from

2018–19, around its 20 year average.

A number of commentators have highlighted uncertainties in

these economic forecasts, and the Budget itself notes the sensitivity of

taxation receipts to these underlying parameters. For a more detailed

discussion of this see the Budget briefing paper Assessment of key economic

parameters.

The Budget papers also reference a number of international

economic risks that could have potential impacts on the Budget’s economic

forecasts, many of which the Parliamentary Library highlighted in its Pre-Budget

Snapshot of the Australian Economy.[7]

The headline fiscal numbers

- the underlying cash deficit is estimated to be

$29.4 billion (-1.6 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP)) in

2017–18 and $21.4 billion (-1.1 per cent of GDP) in 2018–19 before

improving to a projected underlying cash surplus of $7.4 billion

(0.4 per cent of GDP) in 2020–21

- over the four years to 2020–21 accumulated net deficits

are estimated to total $45.9 billion

- total general government sector receipts are estimated to

be $433.5 billion (23.8 per cent of GDP) in 2017–18,

$462.5 billion (24.4 per cent of GDP) in 2018–19 rising to a

projected $526.3 billion (25.4 per cent of GDP) by 2020–21

- tax receipts are estimated to be $404.3 billion

(22.2 per cent of GDP) in 2017–18, $430.7 billion

(22.8 per cent of GDP) in 2018–19 increasing to a projected

$492.5 billion (23.7 per cent of GDP) by 2020–21

- The

largest component of tax receipts is personal income taxes which are

estimated to be $217.4 billion (11.9 per cent of GDP) in 2017–18, $230.8

billion (12.2 per cent of GDP) in 2018–19 increasing to a projected $270.2

billion (13 per cent of GDP) in 2020–21.

- general government sector payments are estimated to be $459.7

billion (25.2 per cent of GDP) in 2017–18, $480.4 billion (25.4 per cent

of GDP) in 2018–19 and increasing to a projected $518.9 billion (25.0 per cent

of GDP) by 2020–21

- general government sector net debt is estimated to be

$354.9 billion (19.5 per cent of GDP) in 2017–18, $375.1 billion

(19.8 per cent of GDP) in 2018–19 declining to a projected $366.2 billion

(17.6 per cent of GDP) by 2019–20

- general government sector net interest payments are

estimated to be $13.4 billion (0.7 per cent of GDP) in 2017–18,

$13.7 billion (0.7 per cent of GDP) in 2018–19 increasing to a

projected $15.5 billion (0.7 per cent of GDP) in 2020–21

- the face value of Commonwealth Government Securities (CGS)

on issue is estimated to be $540.0 billion in 2017–18, $582.0 billion in

2018–19 rising to $606.0 billion in 2020–21. Looking further out the total

value of CGS on issue is projected to rise to $725.0 billion by 2027–28.

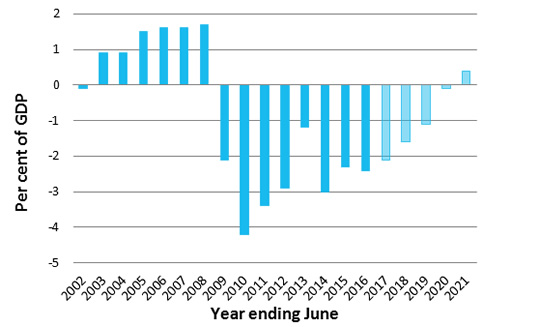

The

Budget deficit is forecast to gradually

improve from a $29.4 billion deficit

in

2017–18 to a $7.4 billion surplus in 2019–20.

Underlying

Cash Balance

| Year |

$m |

% GDP |

| 2015–16 |

-39,606 |

-2.4 |

| 2016–17 |

-37,600 |

-2.1 |

| 2017–18 |

-29,396 |

-1.6 |

| 2018–19 |

-21,422 |

-1.1 |

| 2019–20 |

-2,470 |

-0.1 |

| 2020–21 |

7,417 |

0.4 |

|

Figure

1: Underlying Cash Balance % GDP

Source: Australian

Government, Budget strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1:

2017–18, Statement 11:

historical Australian government data, Table 1, p. 11-6.

|

|

Achieving a surplus depends

on closing the gap between payments and receipts...

- in the last decade payments peaked at 26.0 per cent of GDP in

2009–10 and are estimated to be 25.5 per cent of GDP in 2018–19 before

declining to 25.0 per cent in 2020–21

- in the last decade receipts bottomed at 21.4 per cent of GDP in

2010–11 and are forecast to be 23.8 per cent of GDP in 2017–18 and increase

to 25.4 per cent of GDP in 2020–21.

|

Figure

2: Receipts and Payments % GDP

Source: Australian

Government, Budget strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1:

2017–18, 2017, Statement 11: historical Australian

government data, Table 1, p. 11-6.

|

|

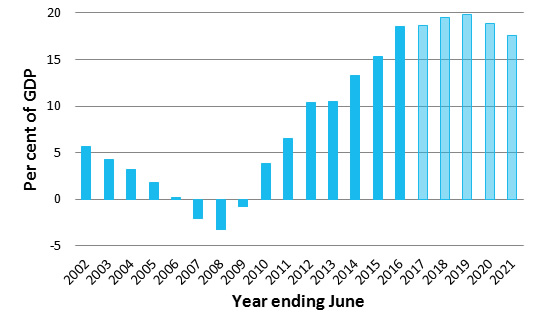

Net debt is forecast to peak as

a percentage of GDP (19.8 per cent) in 2018–19.

Net

Debt

| Year |

$m |

%

GDP |

| 2015–16 |

305,454 |

18.5 |

| 2016–17 |

325,091 |

18.6 |

| 2017–18 |

354,931 |

19.5 |

| 2018–19 |

375,112 |

19.8 |

| 2019–20 |

374,715 |

18.9 |

| 2020-21 |

366,169 |

17.6 |

|

Figure

3: Net Debt % GDP

Source: Australian

Government, Budget strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1:

2017–18, 2017, Statement 11: historical Australian

government data, Table 4, p. 11-12.

|

|

Total personal income tax

receipts are projected to grow to 12.2 per cent of GDP in 2020–21, their

highest level since 2000

Individuals and other

tax receipts

| Year |

$m |

%

GDP |

| 2015–16 |

198,303 |

12.0 |

| 2016–17 |

205,990 |

11.7 |

| 2017–18 |

217,400

|

11.9 |

| 2018–19 |

230,790 |

12.2 |

| 2019–20 |

250,840 |

12.6 |

| 2020–21 |

270,200 |

13.0 |

|

Figure

4: Personal income tax % GDP

Source:

Australian Government, Budget strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1:

2017–18, Statement 5: revenue, online supplementary tables.

|

|

Company income taxes are

projected to grow to 4.6 per cent of GDP in 2020–21,around their highest

level since 2008–09

Company tax receipts

| Year |

$m |

%

GDP |

| 2015–16 |

63,638 |

3.8 |

| 2016–17 |

68,800 |

4.0 |

| 2017–18 |

78,800

|

4.4 |

| 2018–19 |

85,600 |

4.6 |

| 2019–20 |

92,600 |

4.7 |

| 2020–21 |

96,000 |

4.6 |

|

Figure

5: Company Tax % GDP

Source: Australian Government, Budget strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1:

2017–18, 2017, Statement 5: revenue, online supplementary

tables.

|

|

Sales tax (including GST),

excise and customs duties are projected to be 5.6 per cent in 2020–21, close

to their lowest level since 2000

Sales tax, excise and

customs duty

| Year |

$m |

%

GDP |

| 2015–16 |

94,337 |

5.7 |

| 2016–17 |

96,584 |

5.5 |

| 2017–18 |

100,978

|

5.5 |

| 2018–19 |

106,301 |

5.7 |

| 2019–20 |

111,355 |

5.6 |

| 2020–21 |

117,643 |

5.6 |

|

Figure

6: Sales (incl GST), Excise and Customs Taxes % GDP

Source:

Australian Government, Budget strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1:

2017–18, 2017, Statement 5: revenue, online supplementary

tables.

|

|

Indirect taxes are

projected to fall to their lowest proportion of total receipts since

1999-2000, before the GST was introduced

Direct taxes are taxes on income

or profits, Indirect taxes are taxes on goods and services

One of the Government’s reasons

for reform at the time the GST was introduced was

‘the Commonwealth will become increasingly reliant

on income directly levied on individuals... tax rates would rise and the system

become even more unfair as those individuals who had the opportunity to avoid

tax increasingly did so. The indirect tax base would continue to decline

[and] rates would need to be increased again’ [8]’

|

Figure

7: Direct and Indirect Taxes (% of total receipts)

Source:

Australian Government, Budget strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1:

2017–18, 2017, Statement 5: revenue, online supplementary

tables.

|

|

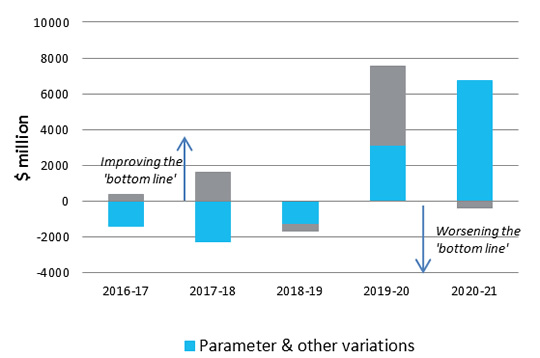

Effect

on the Underlying Cash Balance of changes since MYEFO

| Year |

Policy

measures

$m |

Parameter

variations

$m |

| 2016–17 |

-1,429 |

343 |

| 2017–18 |

-2,299 |

1,599 |

| 2018–19 |

-1,303 |

-407 |

| 2019–20 |

3,128 |

4,394 |

| 2020–21 |

6,724 |

-390 |

|

Figure 8: Effect of

policy and parameter changes

on the Underlying Cash Balance since MYEFO

Source: Australian

Government, Budget strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1: 2017–18, Statement 3: overview, Table 6, p. 3-27.

|

|

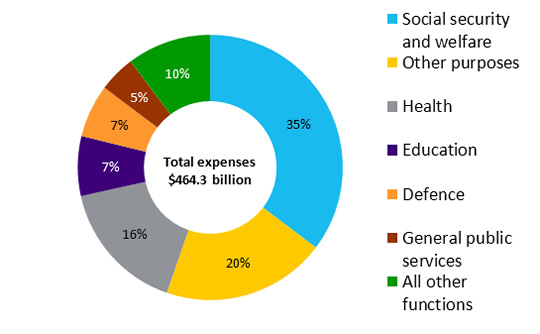

Where does government spending go

in 2017–18?

Estimates

of Expenses by function

| |

$b |

% |

| Social

security & welfare |

164.1 |

35.3 |

| Health |

75.3 |

16.2 |

| Education |

33.8 |

7.3 |

| Defence |

30.1 |

6.5 |

| General

public services |

20.7 |

4.5 |

| All

other functions |

47.6 |

10.2 |

| Other

purposes |

92.8 |

20.0 |

| Total |

464.3 |

100.0 |

|

Figure

9: Expenses by function in 2017–18

Source: Australian

Government, Budget 2017–18, Budget overview, 9 May 2017, Appendix B, p. 25.

|

|

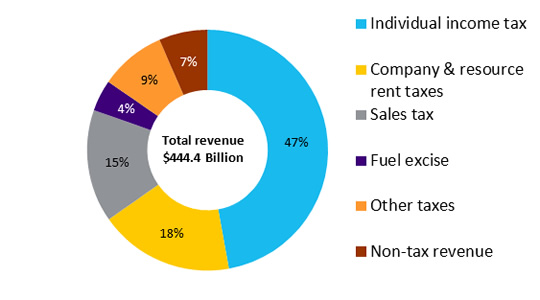

Where does the revenue come

from

in 2017–18?

| |

$b |

% |

| Individuals

income tax |

209.6 |

47.2 |

| Company

& resource rent taxes |

80.4 |

18.1 |

| Sales

tax (incl. the GST) |

67.3 |

15.1 |

| Fuels

excise |

18.7 |

4.2 |

| Other

taxes |

39.4 |

8.9 |

| Non-tax

revenue |

29.0 |

6.5 |

| Total |

444.4 |

100 |

|

Figure

10: Revenue in 2017–18

Source: Australian Government, Budget 2017–18, Budget overview, 9 May 2017, Appendix B, p. 25.

|

The headline economic forecasts

Table 1: Treasury forecasts of

major economic parameters (per cent)

| |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

2020–21 |

| Real GDP |

2.6 |

1.75 |

2.75 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

| Employment |

1.9 |

1 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

| Unemployment Rate |

5.7 |

5.75 |

5.75 |

5.5 |

5.5 |

5.25 |

| Consumer Price Index |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2.25 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

| Wage Price Index |

2.1 |

2 |

2.5 |

3 |

3.5 |

3.75 |

| Nominal GDP |

2.3 |

6 |

4 |

4 |

4.5 |

4.75 |

| Terms of Trade |

-10.2 |

16.5 |

-2.75 |

-4.25 |

|

|

Source: Australian Government, Budget strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1:

2017–18, Statement 1: Budget

overview, Table 2, p. 1-9;

Statement 2: economic outlook,

Table 1, p. 2-6.

The

Budget only forecasts Terms of Trade to 2018-19.

Table A1 provides a

snapshot of how these forecasts have changed since last year’s budget (see

Attachment A).

|

Economic growth is forecast

to improve

Annual real GDP growth is

expected to fall to 1.75 per cent in 2016-17 to due to events related to

Tropical Cyclone Debbie

It is expected to increase to 3

per cent in 2018‑19 and remain at the level, around its 20 year

average, to 2020-21. |

Figure 11: Real GDP

Growth %

Source: Australian Bureau

of Statistics (ABS), Australian national accounts: national income,

expenditure and product, December 2016, cat. no. 5206.0, ABS, Canberra, March 2017.

|

|

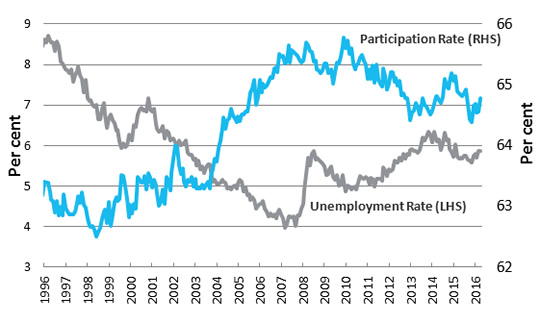

The Unemployment rate is expected

to fall to 5.25 per cent in 2020-21, around its lowest level since 2011-12

|

Figure

12: Unemployment and Participation % of Labour Force

Source: ABS, Labour

force, Australia, March 2017, cat. no. 6202.0, ABS, Canberra, April 2017.

|

|

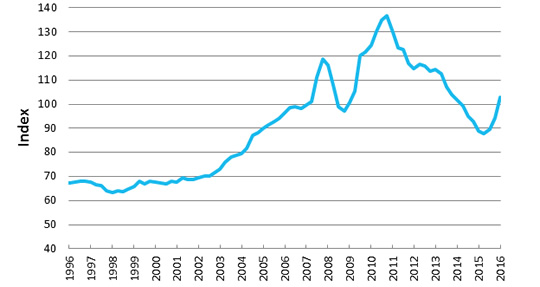

In recent years large falls in

commodity prices have driven a significant decline in Australia’s terms of

trade.

A near-term boost in commodity

prices is expected to improve the terms of trade in 2016-17, before declining

slightly in 2017-18 and 2018-19. |

Figure

13: Terms of Trade Index

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Australian

national accounts: national income, expenditure and product, December 2016,

cat. no. 5206.0, ABS, Canberra, March 2017.

|

|

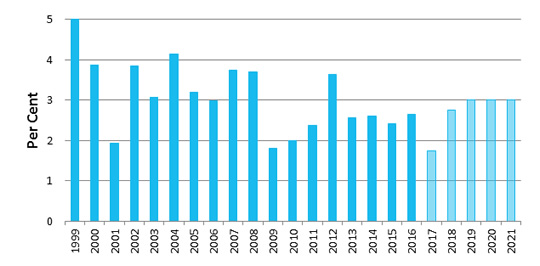

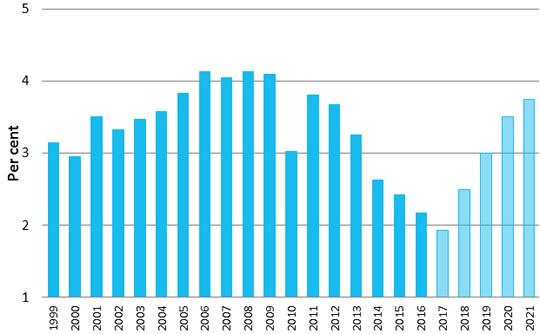

Wage price growth has been

weak in recent times

The wage price index (WPI) is

calculated by comparing the cost of wages over time for the same work level

and output

Annual forecast wage growth in

2016-17 is forecast to be 2 per cent, the lowest rate of growth since the

start of the series in 1998.

Wage growth is expected to be

3.75 per cent in 2020-21 its highest level since 2010-11.

|

Figure

14: Wage Price Index Growth

Source: Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), Statistical

tables, H4 – Labour Costs and Productivity.

|

Attachment A

Table A1: Treasury forecasts of

major economic parameters (per cent)

| |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

2020–21 |

| Real GDP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Budget 2016–17 |

2.2 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

| PEFO 2016 |

2.2 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

| MYEFO 2016–17 |

2.7 |

2 |

2.75 |

3 |

3 |

|

| Budget 2017–18 |

2.6 |

1.75 |

2.75 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

| Employment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Budget 2016–17 |

1.6 |

2 |

1.75 |

1.75 |

1.25 |

1.5 |

| PEFO 2016 |

1.5 |

2 |

1.75 |

1.75 |

1.25 |

1.5 |

| MYEFO 2016–17 |

1.9 |

1.25 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

| Budget 2017–18 |

1.9 |

1 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

| Unemployment Rate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Budget 2016–17 |

6.1 |

5.75 |

5.5 |

5.5 |

5.5 |

5.5 |

| PEFO 2016 |

6.1 |

5.75 |

5.5 |

5.5 |

5.5 |

5.5 |

| MYEFO 2016–17 |

5.7 |

5.5 |

5.5 |

5.25 |

5.25 |

|

| Budget 2017–18 |

5.7 |

5.75 |

5.75 |

5.5 |

5.5 |

5.25 |

| Consumer Price Index |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Budget 2016–17 |

1.5 |

1.25 |

2 |

2.25 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

| PEFO 2016 |

1.5 |

1.25 |

2 |

2.25 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

| MYEFO 2016–17 |

1 |

1.75 |

2 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

|

| Budget 2017–18 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2.25 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

| Wage Price Index |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Budget 2016–17 |

2.3 |

2.25 |

2.5 |

2.75 |

3.25 |

3.5 |

| PEFO 2016 |

2.3 |

2.25 |

2.5 |

2.75 |

3.25 |

3.5 |

| MYEFO 2016–17 |

2.1 |

2.25 |

2.5 |

3.25 |

3.5 |

|

| Budget 2017–18 |

2.1 |

2 |

2.5 |

3 |

3.5 |

3.75 |

| Nominal GDP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Budget 2016–17 |

1.6 |

2.5 |

4.25 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| PEFO 2016 |

1.6 |

2.5 |

4.25 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| MYEFO 2016–17 |

2.3 |

5.75 |

3.75 |

4.25 |

4.5 |

|

| Budget 2017–18 |

2.3 |

6 |

4 |

4 |

4.5 |

4.75 |

| Terms of Trade |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Budget 2016–17 |

-10.3 |

-8.75 |

1.25 |

0 |

|

|

| PEFO 2016 |

|

1.25 |

0 |

|

|

|

| MYEFO 2016–17 |

-10.2 |

14 |

-3.75 |

|

|

|

| Budget 2017–18 |

-10.2 |

16.5 |

-2.75 |

-4.25 |

|

|

Source:

Australian Government, Budget strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1:

2016–17, Statement 1,

Table 2, p. 1-8, Statement 2, Table 1, p. 2-6; S Morrison

(Treasurer) and M Cormann (Minister for Finance), Pre-election economic and fiscal outlook 2016, Table 2, May 2016, p. 16; Australian Government,

Mid-year economic and fiscal outlook 2016–17, Table 1.2, p. 2, Table 2.2, May 2016, p.

11; Australian Government, Budget strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1:

2017–18, 2017, Statement 1,

Table 2, p. 1-9, Statement 2, Table 1, p. 2-6.

[1].

S Morrison (Treasurer), Budget

speech 2017–18.

[2].

This refers to income and other withholding taxes, plus FBT and

superannuation taxes.

[3].

T Clark , A Lukin and D Wood, ‘Treasurer Scott Morrison’s 2017-18 budget speech, annotated

by experts’, The Conversation, 10 May 2017.

[4].

This refers to company income tax plus resource rent taxes

[5].

Australian Government, Budget

strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1: 2017–18, Statement 5:

revenue, p. 5-13.

[6].

This includes the Goods and Services Tax (GST), Wine Equalisation Tax

(WET) and Luxury Car Tax.

[7].

N Gupta, P Hawkins and H Portillo-Castro, Pre-budget

snapshot of the Australian economy: a quick guide,

Research paper series, 2016–17, Parliamentary Library, Canberra, 9 May 2017.

[8].

P Costello (Treasurer), Tax

Reform not a new tax a new tax system – The Howard Government’s plan for a New

Tax System - Overview, report, August 1998

All online articles accessed May 2017.

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.

In essence, you are free to copy and communicate this work in its current form for all non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute the work to the author and abide by the other licence terms. The work cannot be adapted or modified in any way. Content from this publication should be attributed in the following way: Author(s), Title of publication, Series Name and No, Publisher, Date.

To the extent that copyright subsists in third party quotes it remains with the original owner and permission may be required to reuse the material.

Inquiries regarding the licence and any use of the publication are welcome to webmanager@aph.gov.au.

This work has been prepared to support the work of the Australian Parliament using information available at the time of production. The views expressed do not reflect an official position of the Parliamentary Library, nor do they constitute professional legal opinion.

Any concerns or complaints should be directed to the Parliamentary Librarian. Parliamentary Library staff are available to discuss the contents of publications with Senators and Members and their staff. To access this service, clients may contact the author or the Library‘s Central Enquiry Point for referral.