Papers on Parliament No. 61

May 2014

Panel Discussion

Prev | Contents | Next

CHAIR (Ms JACOBS)

— We are now up to the question-and-answer session. I know that we want it to

be free-flowing and spontaneous, so I hope that you all have those questions

prepared.

QUESTION — On the

agenda in the forthcoming parliament will be the recognition of Indigenous

Australians in the Constitution. There have been lots of clues about the early

thought, and particularly from Inglis Clark, about those things in that last

discussion about citizens and equality of rights. We do understand at that time

the Aboriginal people weren’t being contemplated as part of the citizenry of

Australia, but are there any clues or directions in any of that earlier

thinking that perhaps was left out that might provide some direction for the

debate that is ahead of us?

Prof. WILLIAMS —

The debate was premised on the notion that this was a dying people, and there

was very little to be said in the Convention. In fact, in 1890 the New Zealand

delegates were saying that they had sort of solved the problem, and I do not

think they were looking at it in a positive light either. So it really does not

get much of a mention. The whole race power is a very late entry into the

constitutional lines. Samuel Griffith pushes it reasonably heavily there for a

while.

In the 14th Amendment, they are mainly concerned

about what Isaac Isaacs described as ‘undesirable races’. So Inglis Clark had

to respond heavily to Isaacs in his 14th Amendment debate when he was putting

it forward. Isaacs is saying, ‘If we put this in, we will have to treat

subjects of the Queen’—who, of course, as we know, may not have been like

ourselves at that stage. Subjects of the Queen was used to describe Chinamen—

Prof. LAKE — And

Indians.

Prof. WILLIAMS —

Indians—Hindus get a hard run too. Inglis Clark responds to that by saying,

‘Look, we could draft some amendments to this if we needed to’, but he was not

convinced we needed to. It is really interesting to see Isaacs in this debate.

He cites the US cases saying that laundry licences could not be stopped from

being given to Chinese if you have the 14th Amendment. So, I think, no to the

question on Indigenous questions, but Inglis Clark was not, I think, overly

convinced about the argument. But, if it had to be dealt with, he felt there

was a way around it. But the real concern was, of course, he wanted not

subjects; he wanted citizenship.

QUESTION — If

that 14th Amendment had become operative, what would have been the consequences

of the kind of legislation that has just been passed in Queensland as far as

the bikers are concerned? They seem, certainly to me, to be second-class

citizens of a different kind.

Prof. WILLIAMS —

It is very interesting in this country how we have got our rights. It has

really been by a judicial process, apart from the legislative processes, as we

know. The High Court in many ways has had to turn itself inside out with its

idea of the separation of powers. It has been giving us those things—the

so-called Kable doctrine, where what courts can do and what you can make courts

do as it infringes their separation of powers. That is how we have got to most

of the legislation about bikers being struck down, because they have

somehow—the state legislatures—tried to cloak the whole activity by giving it

to a court, and the courts have said, ‘Look, this is not our role; we are not

going to do this’.

The 14th Amendment, if it got in, because of its

due process nature saying that you cannot pass a law that removes due process:

to be heard, all the ex parte events—activities being given without even

your presence known, orders made to tear down and seize without you being

there—they would be real problems. So we have slightly got to that way, but not

through an express statement. It is by an implication about how judicial power

can be exercised.

CHAIR — I wonder

too about how we can make judgements on Clark’s own intentions for the

Constitution and this whole notion of interpretative law. Was that a notion

that was prominent among lawmakers at the time—that we would have black-letter

law or an interpretive vision?

Prof. WILLIAMS —

Not really. There was an emergence with Oliver Wendell Holmes. He wrote a book

called The Common Law, where he tried to unpack the idea that there is

judicial choice and how you make a choice. So, for instance, that is where I

think Inglis Clark comes in. Look, there is a wonderful irony here with a man

who says, ‘How do you interpret the Constitution?’ What does he say? ‘Don’t ask

me’. He says, ‘Don’t ask those who gave it; the Constitution is in your

presence and your problem’. So let us take, just as an example, the word

marriage—for no particular reason. What does the word marriage mean? Well, in

1901 we are pretty clear what the word marriage meant. It was a union between a

man and a woman, and that is, I assume, what the framers meant; we could find

legislation that was influencing them. That is what it would be.

Today, that word may mean a union of two people.

We do not know what the answer is. The Constitution has one word—‘marriage’—that’s

it. The High Court is going to have to turn its mind to what that word means

today and, in coming to that, they could ask what the framers thought in 1901

or they could say, ‘Has that word moved with the times?’ I am pretty sure I

know what Andrew Inglis Clark would say.

Prof. LAKE — Can

I say something? The Common Law, which I talked about in my paper this

morning, was so important to Andrew Inglis Clark and it was precisely that

understanding that it was a living force, that law had to adapt to current

circumstances. What is really interesting about the intellectual exchange is

that not only does Andrew Inglis Clark seize on Wendell Holmes’ classic

textbook, as he calls it, The Common Law, but when H.B. Higgins goes to

the United States a couple of decades later he is received as a celebrity

because he has become a leader in developing a ‘new province for law and

order’, in framing a jurisprudence, as they said, to meet the industrial needs

of the time. It is that emphasis on meeting the industrial and social needs of

the time that led US jurists to acclaim Higgins’ work as so innovative and so

important. We need to locate Australian jurisprudence historically within that

larger debate.

Prof. WILLIAMS —

The jurisprudence was crushed in a sense by Owen Dixon’s intellectual

prominence during the 1940s and 50s. There was just nowhere else: you were

either with Dixon or you were not, and that was it. The re-emergence of

Clark—and this is why he has emerged—is because a number of High Court judges

have found Clark as a way of giving some tools towards how to interpret the

Constitution.

Prof. LAKE — I

thought your point towards the end was fantastic, that Clark’s significance was

as a theorist of the Constitution, as a theorist of constitutional law, rather

than as part of a fairly arid debate about national founders.

Dr BANNON — I

will just add something quickly apropos appointments to the High Court. This is

a very interesting discussion. What would Clark have been like as a High Court

judge? He was obviously very fitted and skilled and qualified to do it. He was

dudded twice, and so was Sir John Downer.

Just to briefly sketch, the concept of the High

Court was that there were to be five places. Remember, in Charles Kingston’s

draft Constitution he kept emphasising that there would be five drawn from the

five states, but there were six with Western Australia. But Western Australia’s

judiciary was regarded as not developed enough or mature to provide a judge and

there were no great jurists from there. So you have five and each of the

colonies could have been represented in that first federal court—and they were

on a promise. Downer was certainly on a promise from Edmund Barton, his great

mate, the Prime Minister at the time: ‘You will be on’. Isaacs thought that he

was going to get there but he did not realise how much he annoyed Barton. Then

the Act was changed to reduce the numbers from five to three, and suddenly

there was a problem. Two had to miss out. Downer was assured by Barton—‘that’s

all right, you’re safe; we’ll get rid of Isaacs’. And Clark—‘you’ll be okay

too’. So both of them confidently expected to be appointed.

Then Barton decided he was a bit tired of being

Prime Minister and wanted to get out, so he became one of the appointees. Barton,

Griffith and Richard O’Connor—two New South Welshmen—became it. Downer would

not speak to Barton for another five or six years and boycotted receptions of

the High Court in Adelaide through that period. Clark may have sulked but he

did not do anything. In 1905 they decided, ‘Yes, we’ve got to increase the

court by two more places. We probably have to have a Victorian on so Isaacs

might get his opportunity’. But there was also Clark and Downer who have been

waiting in the wings. Deakin could not really stand Downer and he did not get

on with Clark. Downer thought Alfred Deakin had promised him but he did not and

in the end Downer missed out.

But Clark had definitely been promised by

Deakin. So there is the second casualty. Clark never spoke to Deakin again

after being dudded in this way. We were robbed of two very interesting judges,

both of whom had been involved in detailed drafting of the Constitution. How

that five-person bench would have interpreted through the next decade is a very

interesting discussion but it would have been very much more fruitful in terms

of this ‘realist’ approach, I suspect.

CHAIR — I want to

sneak in another question on the notion of what kind of vision of the law Clark

had. Let me throw to you, as a South Australian, the question of the New South

Wales view of federation, which I think Rosemary read in Helen’s paper, and

perhaps the Victorian one, too. How significant is it, when we are thinking

about these questions, that Clark was Tasmanian? How much did that influence

his view of law?

Dr BANNON — It is

very important. You just have to go 100 kilometres outside Sydney or Melbourne

or the Canberra axis and you have a very different view of what the federation

of Australia is, and it is not fanciful. We keep voting no in referendums in

large part because the outer states—and the further you are away from Canberra,

the bigger the no vote is—are suspicious of things emanating from and

generating from here. An embracive approach to referendums might in fact

produce different results. So the concept of the federation that Clark had,

that Kingston and others had, was very different. It was interesting that with

that court, as I have just illustrated—two New South Welshman and a

Queenslander—we were never in the fight. The next two were both

Victorians—forget about the peripheral states. South Australia to this day,

2013, has had some great jurists but never one member of the High Court of

Australia. What a scandal.

QUESTION — It

seems from what has been said today that, because we cannot predict the future

with great confidence, at least Clark among the founders and possibly others

thought that legislators should be able to adjust to the times and that people

should be able to adjust to the times, but this has been very difficult with referendums

being declined every now and again. One wonders whether Jefferson’s idea that a

constitution should last for 20 years or less might have been right.

CHAIR — I find

very interesting the notion that Clark was recognisably modern. I wonder, too,

whether that was the same thing as being recognisably American, what kind of

shared territory there was there.

Dr LAING — I

think Helen’s paper was suggesting that it is a mistake to put a modern

framework over Clark’s views and that really what we are doing is a wish

fulfilment: we think he was a great supporter of human rights and if only

everyone else had listened to the way he wanted to do it we would have had a

bill of rights in the Constitution. I think she was casting doubt on that.

Prof. LAKE — I

think it is an odd conception in this context, ‘modern’. What we were talking

about before was that there was a receptiveness to a certain approach to law

and interpreting the Constitution that made Andrew Inglis Clark responsive to

Oliver Wendell Holmes’ approach, but that that in turn developed in Australia

in a quite innovative way, that we have also completely forgotten. The esteem

in which H.B. Higgins was held in the United States was quite amazing, but we

have no memory of that. I think we are talking about different approaches to

law. Owen Dixon comes much later, but he was not modern in that sense.

Prof. WILLIAMS —

The High Court does not come into operation until 1903, so there are a number

of years where the state Supreme Courts are interpreting the Constitution and

you will be surprised to find out that they interpret to their advantage and

not the Commonwealth’s. So states put taxes on their wages and the state

Supreme Courts say, ‘That’s great, fine, you can tax them, no problem’. Inglis

Clark does not believe that because he believes there is a central role and a

capacity of the Commonwealth. He writes a letter to another judge. One of these

cases comes down and the Victorian Supreme Court essentially knocks down some

Commonwealth legislation. Inglis Clark is fuming about this and he writes to

Deakin:

Since I came home I have read Madden’s

judgment on Wollaston’s case and felt so much irritated that I could not rest

until I had relieved myself by writing a criticism of it. à Beckett’s judgment

is a sober and respectable performance which deserves attention, although I

believe that he has arrived at a wrong conclusion. Madden’s production is full

of false history, bad political science, bad political economy, bad logic and

bad law.[1]

Now what is interesting about that list is you

would not expect a judge to say that a judgment is bad in history, bad in

politics, bad in economy, logic and then finally get to law. This is the legal

realist. This is the man who sees the law in its broader context. Again, it is

coming back to a laboured point, but I think it is very interesting to see how

Clark is not the black-letter lawyer, which central casting would suggest he

should be.

Prof. LAKE — If I

could just add to that. I talked probably more in my paper than others about

Clark and race and racial exclusion, and Clark shared that with most radical

progressives of the time. So that was very modern too, but it is not modern to

our eyes or to our sensibilities. We think it is completely reactionary. To go

back to the point about race and the Constitution, Clark, Deakin and Higgins

were very much believers in the idea that to have an egalitarian radical

democracy you had to exclude other races and castes.

CHAIR — That is

simply the social default of the time. It is a cultural precept that is now

completely obliterated.

Dr HEADON — I

want to move off in a direction that picks up on what John was talking about in

his talk on the podium. It seems to be the elephant in the room that was raised

in the earlier question—that is, the straight reality of constitutional change,

the impasse whereby of 44 referenda only eight have passed. So we have talked

today about ideal republicanism, we have talked about enlightened citizenry, we

have talked about the notion that the Constitution should be a living force,

which necessarily means an enlightened citizenry and/or politicians that are

responding. But in fact we have at this moment the opposite. I am interested in

what the distinguished panellists think. How do we react to this terrible

elephant in the room?

CHAIR — It is a

terrific question, David, because what you are implying is that the vast

majority of Australians are not very interested in an active Constitution at

all. They could not be less interested in an active Constitution.

Dr HEADON —

Seemingly so. And it is not just that we say the average Australian. You would

be naming a number of politicians who have made comments that seem to be

equally unenlightened. What do we do?

CHAIR — As you

say, the overwhelming number of referenda have been defeated and some of them

very heavily indeed.

Dr BANNON — Why

is that seen as necessarily not the will of the people? On the contrary, I do

not think people are uninterested in referenda; they are just very suspicious

of changes emanating from a unilateral decision through the national parliament

and if in doubt, they vote ‘no’. But they are also valuing their Constitution.

Whether it is in the right way—because they have rejected some very sensible

questions—one doesn’t know. But there is a value seen in the Constitution so

you have to be very careful about changing it. But if there is some real

national cause that people are taken on, such as the 1967 Aboriginal

referendum, they will vote overwhelmingly ‘yes’. So it is not as if they are

being stupid, this is a choice Australian people are making.

Prof. REYNOLDS —

There is a fundamental point, John, that when the Constitution was framed,

there were not political parties in the sense that we know them today. As we

know, if you have got a referendum and the political parties take different

sides, as they almost certainly do for political reasons, even though they

might have supported the thing in the past the opposition will oppose it

because the government is proposing it. Now if that is the situation then it is

almost impossible to get a majority of voters in a majority of states. The

party system is what has made passing things very difficult because there are

very few occasions when all sides will support the one issue as they did in 1967.

So it does seem to me that there is a problem. If you ever taught the

Constitution, as I have done, and gone through it, there is a great deal which

simply no longer really has any relevance and there are enormously important

things that are not there. It really is a document that should be profoundly

changed. But how that is done, I think, is almost impossible to suggest.

CHAIR — I think

this is a particularly interesting discussion to be having as we face the

prospect of a Senate re-election in Western Australia with a ballot likely to

be the size of that table cloth and the questions about what an exercise of

full-blown democracy actually achieves in terms of our national progress.

QUESTION — I was

just wondering what reaction Andrew Inglis Clark had to the ideas of Henry

George, given that some of the things that he promoted were definitely on the

Georgeist platform.

Prof. REYNOLDS —

Henry George did not have a particularly large influence in Tasmania, although

he was discussed. But he was certainly very interested in taxation. One of the

most important areas where he tried to bring about significant reform was

indeed taxation. And in particular he wanted to make sure that tax was on the

unimproved value of land, so you did not end up taxing the small farmer or the

orchardist who was improving things; you taxed the pastoralist who was not

doing much with the land. Clark was very aware of the importance of class and

taxation, but I would not have thought he was a Henry George disciple by any

means. But he certainly saw tax on land as being a very important way to both

raise revenue and bring about social change.

Dr HEADON — We

are aware that it is sort of the generalisation that it was progress and

poverty of 1879 that, one way or another, stayed in the heads of enough of the

key politicians that the national capital would have leasehold title rather

than freehold title.

CHAIR — Which was

the very reason why Queanbeyan didn’t join in, because they didn’t want to give

up their freehold.

Dr HEADON — Yes,

yes. And the high point probably for George was the trip in 1890 when he came

here and played to packed houses, but then you get a quite sharp diminishing.

But since we are in Canberra and since I mentioned ever so briefly Walter and

Marion Griffin this morning, I think a number of people in this room are aware

that (notwithstanding that the Henry George tide had well and truly gone out by

around about the time of federation), when Walter Burley Griffin came here in

1913, he came as a convinced single taxer. The two most significant lectures he

ever delivered in Australia from the time he arrived all the way through to

1935, were the two lectures that he delivered to the Henry George society in

Melbourne, especially the one in 1915, when the troops had only just arrived at

Anzac.

QUESTION — It was

my impression that Professor Irving raised the notion that the very absence of

a bill of rights in some ways perhaps might have actually allowed for the

emancipation and the furthering of rights of certain groups. For instance, the

women’s movement was mentioned. I am interested if the panel in general felt

that was the position she was trying to advocate and whether they agreed with

her, and also whether they might be able to expand on what examples of that

could be, or what it could mean in real or concrete terms.

CHAIR — My sense

that what Helen was suggesting was that the presence of a bill of rights in the

US did nothing in particular to advance the cause of women’s suffrage, that we

go back to the cultural and social precepts of the time and what people’s

understanding of suffrage and citizenship was—but Rosemary?

Dr LAING — The

other part of that observation, with which I concur, is that we could achieve

votes for women in federal elections by ordinary legislation without a bill of

rights. You didn’t need a bill of rights to get to that point. Is it

frightening the horses to have a bill of rights? I don’t know.

Dr BANNON — Well,

indeed, I think we should be grateful we did not have a bill of rights because

I am not quite sure what they would have put in it. But I suspect one of the

first things that would have gone in, because of one of the first pieces of

legislation passed, would have been the White Australia policy. We would have

found that entrenched in the Constitution and extracting ourselves from

that—and it took a bloody long time—would have been very much more difficult.

CHAIR — And the

definition of citizenship, presumably, might have constituted part of the bill

of rights, and who knows what that might have included at that point.

Prof. LAKE — One

of the points Helen mentioned, which is worth mentioning again, to go back to

Higgins and industrial relations, is that the Australian colonies and states

were far more advanced in legislating for a minimum wage and maximum hours and

that these things were always knocked back by the courts in the United

States—the Lochner era, as she referred to it. So, yes, there is a lot of

evidence that you can do things through legislation that you can’t necessarily

do by giving power to a supreme court.

Prof. WILLIAMS —

Though the industrial one is the other example of judicialisation of a lawless

area. O’Connor and Higgins, as we know, were the first and second presidents of

the industrial court, which are High Court judges. So the new province of law

and order as an idea of imposing a judicial solution into—

Prof. LAKE — Into

that province.

CHAIR — And the

interesting point made too about the separation of powers, which is just

integral to that argument. It is interesting to see the resistance of the

Queensland judiciary at this very moment—the growing opposition.

QUESTION — Dr

Bannon, you mentioned the Sydney, Canberra and Melbourne triangle and that

outside that, everyone votes ‘no’ in referenda. Well, it wasn’t until 1977 that

the good citizens of Canberra even had the right to vote in a referendum on

altering the Constitution. Can I ask the panel: what role did Andrew Inglis

Clark make in the drafting of section 125? Or was that something after his

time?

Prof. WILLIAMS —

No, he was all over section 125. Section 125, as you know, is the capital. In

his draft he would have changed Canberra immeasurably, because he said it could

only be 10 miles square. He literally picked up the US one and dumped it in

there, so it would have been a much smaller capital, essentially the

parliamentary triangle.

CHAIR — ‘Inside

the Beltway’, so to speak. David, do you have comments?

Dr HEADON — Well,

only thank heavens for King O’Malley’s motion in July of 1901, suggesting 1,000

square miles because of the speculation—the brutal speculation—that took place

in the US.

Dr BANNON — We

might add that it is only a constitutional fix that has it so close to Sydney

and based in New South Wales. I mean, there are many more logical places in

relation to the fulcrum around which Australia revolves.

Prof. WILLIAMS —

Inglis Clark says ‘to exercise exclusive legislation in all cases whatsoever,

over such but not exceeding 10 miles square that may be ceded to be the seat of

government’.

QUESTION — I

wanted to go back to the 14th Amendment and Indigenous Australians. Maybe I am

wrong on this but the 14th Amendment grew out of the Civil War and the

reconstruction period and the interpretation that had been given before the

Civil War by the Supreme Court that slaves were not citizens. The adoption of

the citizenship clause immediately gave them some sort of standing. Whatever

else they were lacking, they had that. Now, had we had the citizenship part of

the 14th Amendment that may well have, depending on interpretation, had an

effect on Aborigines. If they had been formally defined as citizens at that

point, because of their having been born here and so on, then that might have

changed some of the discourse, at least a bit later, not perhaps quite in 1901

but would have presented a possibility of working around that. Or am I too idealistic

about that?

CHAIR — Well, I

would imagine that the argument that we have made already that Indigenous

people would be quite deliberately excluded is the more likely possibility.

But, Henry Reynolds, would you like to comment on that? Would it have done any

good?

Prof. REYNOLDS —

Well, it is very hard to know. There are numerous critical things but one is

that quite clearly the view was that the Aborigines were a dying race. This was

not just a popular view; it was the view of most men of science, and that

literally there was no future. Andrew Inglis Clark in particular, I am sure,

was convinced that Truganini was indeed the last Aborigine. He may well have

been aware of that community in Bass Strait but, as far as I know, he never

said anything about it. Most Tasmanians did not even know it was there at this

time. So it is not surprising that there was almost no discussion whatsoever

and of course what it meant was that Aborigines were left to the states and the

states had a wide variety of ways of dealing with the situation. In a funny

sort of way in the colonial period the myth was that at least in theory they

were the same as everyone else because they were British subjects.

Clearly, that began to change when the colonies

began legislating. In particular Victoria first, but in a way the real pattern

began to be set in 1897 when Queensland legislated for the protection and

control of Aborigines and the other states and territories followed in the next

20 years or so, which created a situation where indeed they literally had

almost no rights at all. What they might have simply exercised could be taken

away by state governments, and that continued to be the case right up until

living memory, certainly in my living memory.

CHAIR — I think

that it is very easy for us to conflate radical politics at the turn of the

century with radical politics today of any kind. They are not at all the same

thing. If we think of people who were adherents of what they saw as modern

scientific thought—that was phrenology, that was eugenics—all kinds of things

that were on the outer extremes.

QUESTION — One of

the features of Andrew Inglis Clark’s draft that was very much US influenced

was that the Senate was created as the states’ house and given strong powers to

match that role. How do you think the power granted to the Senate, the house of

review, would have been different had it been contemplated that the Senate

would end up as a party house instead of a state house the way it is now?

Dr LAING — Well,

of course, as a parliamentary officer I am not going to say anything too

radical, but I would remind you that domination by parties was not something

that was unforeseen in the 1890s. We have got Deakin taunting Inglis Clark

about the state of the US Congress. We have got John Macrossan who is a

Queensland delegate to the 1891 Convention who actually dies during the

Convention. It was Macrossan who pointed out that: let us not fool ourselves

that senators will vote along state lines; that they will belong to political

parties and political parties will come to dominate the process. So I do not

think that they were unaware. They did not know about modern political parties

as we know them, but they all had alignments and allegiances, so I think that

proto-political parties were certainly well in operation in all the colonial

parliaments. I do not think that it would have surprised them too much to

understand that of course there would be divisions within states about, you

know, the free traders voting against protectionists, for example, and state

lines would not necessarily determine voting. But I think that what is

underestimated is—and this is probably a bit of a hobbyhorse of mine—the way

that the Senate does operate as a state and territory house to this day. There

are many issues of great concern within states and territories that unite

people across party lines. There are many issues that get an airing in the

Senate because they are state issues and the Senate is the place to air those

issues. I think that there was too much emphasis on voting—

CHAIR — Can I

just interject. Rosemary, I just want to put to you that political parties were

much more fluid entities in those days. People swapped sides much more easily.

They changed their positions. We look at the origins of the modern Liberal

Party, for instance, which comes from a number of different sources, and that

fairly rigid cohesion of a two-party system is something with which I think

they could not possibly have conjured.

Dr LAING — Well,

they could see it in America.

Prof. LAKE — The

Labor Party had already been formed by the turn of the century.

Dr LAING — Don’t

forget the layout of a parliamentary chamber. You’ve got government; you’ve got

opposition.

Prof. LAKE — Yes,

and free trade and protection were quite—

Dr BANNON — I

just think, as Rosemary said, there was a prediction that party would be a

factor. Just how big a factor was perhaps unknown. But there was one other

element to this, which is the equal representation power. And the fact is,

within the respective party caucuses, the smaller states have a much bigger

voice because of the Senate’s existence. If Tasmania has got the minimum

five-seat guarantee in the House of Representatives, it has also got exactly

the same number of senators—12. On a proportionate basis, they would not be

there. So that has been a factor throughout federation, particularly since

proportional representation, each state polity produces, some of them, very

peculiar results. But they are what they are: different compositions of the

Senate. There is Nick Xenophon in South Australia, probably an outstanding

example, not repeatable in other polities. He is something peculiarly South

Australian. And so one can look at other minor parties that do better in some

states—such as the Greens—and not so well in others. There is this kind of

fluidity in the Senate that represents small states and, I think, has preserved

the principles of the founding fathers.

Prof. LAKE —

Equality of representation is clearly one of Clark’s Americanist legacies. But

as a Victorian I can fully understand why Higgins opposed that completely as

being undemocratic. It is so fundamentally undemocratic that—

Dr BANNON — Not

in a federation.

Prof. LAKE —

Well, you know—

Dr BANNON — In a

unitary state, yes.

Prof. LAKE — All

I am saying is it is debatable and it was perfectly understandable why that was

a matter of fierce debate about whether you would have Tasmania having the same

number of representatives in the Senate as New South Wales, and I think it is

still a matter of debate. Secondly, on proportional representation, this is

ironic as well, because it is also one of Clark’s legacies, and again as a

Victorian I am not sure what he would have thought about the Motoring

Enthusiast Party—you know, the person they got up, who now seems to have

disappeared. In other words, how proportional representation has played out

surely was quite unforeseen and is very undemocratic. But I guess John Bannon

would think this is healthy democracy expressing itself.

Dr LAING — And it

is not necessarily proportional representation; it is the type of proportional

representation that you have when you number all of the boxes on the Senate

ballot paper.

CHAIR — And can I

just add: will no one remember that you are standing in a city of 350,000

people with two senators? Something of a sore point for many citizens of

Canberra, I think.

Prof. REYNOLDS —

We are aware of that. I remember the whole point of proportional

representation. I mean, there were two things: that it gave you an accurate

representation of the will of the people, but the other fundamental thing was

that it gave minorities the ability to not be crushed by majorities. That was

absolutely central to the whole idea of proportional representation.

Prof. LAKE — You

get 0.05 per cent of the vote and win a seat.

Prof. REYNOLDS —

Yes, well—

QUESTION — Ever

since the Second World War there have been very intelligent people in

Australia—very educated, including professors of law—who have said that we now

have a Constitution which is frozen, which is archaic and which has to change,

but it is just almost impossible. I would say that it is better that we start

talking about rewriting the entire Constitution. The word ‘rewriting’ somehow

is avoided in Australia, but it is the sovereign people, surely, who have the

right to rewrite their Constitution.

Prof. WILLIAMS —

Given that we cannot change a comma in the thing I do not think we are going to

have much chance changing the whole thing! Where would you start? In some ways

the framers did have a degree of intergenerational generosity. There is a

capacity to make policy decisions that are not subject to the Constitution. You

can have different policies on health—they change with the government. And that

is the way it should be, there is no doubt about that.

There have been workarounds; that is the way we

have solved a lot of these issues. The Commonwealth does agreements with the

states—usually tied grants. But there have been ways to work with these. Where

would you start? Obviously, the environment is an issue that is not mentioned

in the Constitution. And Indigenous recognition is something that is going to

come up—hopefully, in the life of this next parliament—which I expect may have

a chance of changing.

A fully-fledged rewriting assumes that we are a

sovereign people—and I am glad you raised that—but whilst our Constitution is

in fact an Act of a foreign parliament, we are not a sovereign people. If you

wanted to know what the republic was all about, it was about saying that our

Constitution is ours. It still is an Act of the British Parliament. One of the

Acts that went immediately before our Constitution was a dog Act. After it

there were things about mining and railways. If you look at the notice sheet

for the day the Australian Constitution was going through, it was just a normal

day in parliament. ‘Oh, we’ve got the Australian Constitution. Well, no, we’ll

put that one through as well’. So rewriting our Constitution as a sovereign

people is a great idea, and one of those steps is actually making it a sovereign

document of our own.

CHAIR — Quick

comment from you, Henry?

Prof. REYNOLDS —

I said earlier that if you teach it and you go through it there is so much in

it that is now virtually redundant, but there is also so much about the system

which is not in the Constitution. These politicians who had all run their

colonial parliaments just assumed so many things that continued but are not

mentioned in the Constitution. There is also the extraordinary position of the

authority of the Governor-General. It clearly needs to be drastically

rewritten—not that I expect it will happen in my lifetime.

QUESTION — I

would like to invite David Headon to respond to the following comment. I think

it is worth drawing attention to the fact that the Australian Capital Territory

uses the Hare–Clark system for the Legislative Assembly, and that was confirmed

by referendum. And it is also worth pointing out that in the ACT there is no

representative of the Crown, so it could be seen as a republican form of

government. It seems to me that the ACT, at the territory and local level, has

the greatest influence of Inglis Clark than any other jurisdiction in

Australia. I invite you to comment on that.

Dr HEADON — Yes,

certainly this is no field of expertise of mine. There are others who are much

better qualified than me to talk, even though we are talking about the ACT. But

essentially I agree with that. If there were to be an emergence of

independently minded politicians, I think the future of the ACT over the next

10 and 20 years could be a very interesting one.

CHAIR — I think

one of the other consequences that we would face if the rest of the nation were

to adopt Hare–Clark would be minority government forever more. That is the

reality of what takes place.

QUESTION — This

follows up on the question about rewriting the Constitution. One of the price

tags, of course, of rewriting it would be that we would then have a new

constitution that potentially would have bugs in it. I would like to get a feel

for what it was like the first time in 1901. Did our Constitution have lots of

bugs in it? Or did it basically work as soon as it was booted up? Did we have

to spend a few years building a few institutions like the High Court? Or is it

possible that we simply only got it to work by ignoring most of it?

Prof. WILLIAMS —

I am just buffering up as I try and work up an answer! Look, there were some

amendments early on, and we were quite successful in the first decade. There

were two amendments, and another one or two nearly got up as well, so there was

much more appetite for changing things.

The first 20 years were pretty steady as you go,

although many of the debates that were going on in federation just kept going

on in the High Court, to be honest. Higgins never gave up, and ultimately in

1920, the Engineers’ Case radically changed the way the interpretation was. I

think it was an easier start. Western Australia had a five-year tax holiday,

effectively, on excise, so their reluctance was assuaged by a bit of money.

One of the wonderful moments, I think, of this

whole federation question when it happened is that wonderful image of the

inauguration of the Commonwealth. You have all seen the slow footage: everyone

walks up—it’s the black and white, it’s the Salvos who did the work. What is

not seen is a commentary that came from Robert Garran, who we all know well

here, when he picked up the letters patent and he picked up the draft

Constitution and all the ministers’ commissions. He put them in a bag and took

them home. The whole archive of the Commonwealth of Australia was taken home by

the one public servant we had!

So the Commonwealth only existed on paper—that

is the point I am trying to make, and it took a while to get underway.

CHAIR — I think

the gist of that is leave it to the lawyers and the public servants. Rosemary,

a final comment from you?

Dr LAING — A

quick comment, and that is that many of the institutions that the Constitution

set up were familiar. I talk about chapter I: the legislature. Well, it was

just an upper and a lower house—a lot like people were used to working with in

the colonies. They had the first elections, everyone turned up in Melbourne on

9 May 1901 and off we went, just like we usually do. So there was that element

of familiarity and continuity in some of the important institutions of state,

and I expect that the governors of the colonies, the Governor-General and

executive government had that similar kind of continuity.

The High Court was new and it really had to wait

for legislation in 1903 to establish that. But in terms of the basic

institutions of government, they were familiar.

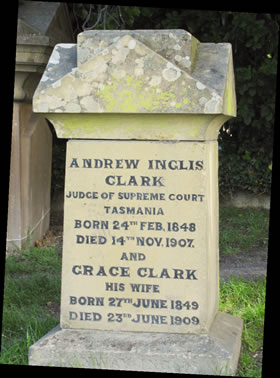

CHAIR — Ladies and

gentlemen, I think we have had a quite impassioned discussion and I am

certainly being given the wind-up signal. We could probably all talk another

half hour or so. But for all of our impassioned argument about his

significance, the reality is that Andrew Inglis Clark’s grave lies almost

forgotten among a small tangle of headstones, and his name is certainly little

known to most Australians outside circles such as these. I suppose it might be

possible to argue that Clark’s legacy is a notion where by and large we have a

substantial and mostly well-warranted trust in the foundations and the

mechanics of our government. That is something which we are very used to in

this nation, but which perhaps we should consider more fully.

Photograph courtesy of James Warden

As we move through the second decade of the

twenty-first century perhaps we should consider that our constitutional

heritage does contain many different strands—many of those illustrated by the

discussions we have heard today. We are sometimes apt to forget that it

includes radical new thought and it includes high political passion and a

vision for Australia, and that should not be obscured by the sometimes duller

reaches of constitutional argument. I do not think we have plumbed many dull

reaches today. It has been a fascinating discussion, and for that I would like

to thank all of you. But most particularly, please join me in thanking our

panellists.

[1] Clark to Deakin, 4 March 1903, Deakin papers, National

Library of Australia, MS 1540/1/850.

Prev | Contents | Next