Papers on Parliament No. 51

June 2009

Prev | Contents

I have thought that we sometimes too slavishly follow a body that is to some extent analogous to ours, but which is certainly not so altogether. We are not on the same footing as the British Houses of Parliament. We are a new body. We are a Federal Senate. We have a certain analogy with the British Parliament, but only to a small extent; and it is about time that we struck out and thought for ourselves, and adopted a phraseology suited to our own circumstances and conditions.

As to the man in the street trying to read and understand our standing orders, I do not think there is any such man.

Senator Sir Richard Baker

President of the Senate[2]

The standing orders of a parliamentary institution reveal much about its character and origins. The degree of borrowing from similar institutions and adaptation for local conditions are particularly important measures. So too is the extent to which an institution’s standing orders are a dynamic body of rules, responding to altered functions and remaining relevant to the institution as it develops over time and is populated with new generations of members.

Since the Senate first ‘struck out’ in 1903 and adopted standing orders that were partly borrowed from the colonial legislatures and partly adapted to suit new circumstances, powers and conditions, there has been much thought given to procedural matters by senators and clerks alike and many innovations have been tested and absorbed into the rules.

In charting the origins and development of the Senate’s current standing orders, this work also provides a history of the institution albeit from a somewhat Lilliputian perspective. While President Baker may have been correct in his assessment of the interest of the man in the street in such matters, there are, nevertheless, in these ‘biographies’ of the standing orders, glimpses of unexpected drama and suspense, human interest and insights into the professions of parliamentarian and parliamentary clerk, against a backdrop of twentieth century Australian political history. The value of procedures based on fair play, and respect for the institution and the rights of individual senators in facilitating rational deliberation, is evident throughout these pages.

Annotated standing orders

In the field of bibliographical studies, an annotated edition of a work includes the full textual history of variations between and within editions. More commonly, ‘annotated’ means the inclusion of commentary to elucidate a text.

Annotated editions of legislation containing commentaries and case notes can be an invaluable resource for legal practitioners, and may also have wider appeal. An illustrious example is Quick and Garran’s Annotated Constitution of the Australian Commonwealth, published in 1901, in which the authors provided commentaries on each section of the Constitution, its origins and evolution through the convention debates. There have also been several legislatures whose officers have produced annotated editions of their standing orders, including commentaries and historical notes. In recent years, the Canadian House of Commons issued a second edition of its annotated standing orders, following the first edition in 1989. The work is also published online.

This volume is intended as a series of commentaries showing the origin, development and current use of each of the standing orders of the Senate. It is not a strict textual study for its own sake but textual changes are noted where they are changes of substance, and the student of bibliography will also find in the appendices a complete list of the 24 editions of Senate standing orders published from 1903 to 2009, collated for the first time. Its focus is on what we have now and where it came from, not on everything there ever was and where it went. Thus, deleted and defunct standing orders are not generally noted unless they were transformed into, or influenced, something extant.

The idea of an annotated edition of the standing orders of the Senate is not new. After the fourth edition of the standing orders was published in 1937, Senate officers compiled such a work but it was never completed. In keeping with frugal times, with the country still gripped by the Great Depression and Canberra barely more than an isolated backwater, those officers compiled the typescript of the work using the back of recycled mourning stationery left over from the death of Edward VII in 1910 during the Senate’s time in Melbourne.[3] The quarto sheets were held in safekeeping, together with a flimsy carbon copy of the typescript, and eventually bound into a thick volume for preservation, probably in the late 1960s or early 1970s.[4] The flimsies, held in two spring back binders along with some additional references, show signs of subsequent use and annotation, particularly those sections dealing with financial legislation.

Internal references suggest that the work may have been intended for publication.[5] For reasons unknown, publication did not proceed. In practical terms, the outbreak of the Second World War, the need to conserve paper supplies, and the inappropriateness of devoting funds to the publication of what would have been a large book with a small potential readership and limited public interest could all explain why publication did not proceed then. Indeed, it may have only ever been intended for internal publication for the use of senators, but even that did not eventuate.

We have disappointingly scant information about the interests of the clerical staff in these years. R.A. Broinowski, who succeeded G.H. Monahan as Clerk in 1938, was better known for his work in establishing the rose gardens at Old Parliament House than for his procedural accomplishments.[6] In 1942, J.E. Edwards became Clerk and a young J.R. (Jim) Odgers joined the staff of the department after five years with the parliamentary reporting staff and the Joint House Department. Edwards had begun to write scholarly articles for journals during the 1930s, including on the Senate’s new Regulations and Ordinances Committee, established in 1932, of which he was secretary. He also wrote an important article on the financial powers of the Senate in 1943 and a small monograph entitled Parliament and how it works, which he updated at regular intervals after its first publication in 1946.[7]

Encouraged by Edwards, Odgers embarked upon a course of study and self-improvement which was to culminate, in 1953, in the publication of the first edition of Australian Senate Practice. This treatise on the institution of the Senate as one of the essential checks and balances under the Constitution ranged far more widely than commentaries on the standing orders but internal references show that it undoubtedly had its origins in that earlier work, particularly the sections on financial legislation and the powers of the Senate in relation to request bills. Through successive editions in 1959, 1967, 1972 and 1976 (the last three during Odgers’ tenure as Clerk),[8] this increasingly confident and polemical work probably overshadowed completely the more pedestrian studies of the standing orders. Furthermore, after the 1937 revision of the standing orders, it would be more than 28 years before the next Standing Orders Committee review and reprinting of the volume occurred in 1965–66.

Institutionally, the Senate was stirring after a long hibernation and beginning to rediscover its constitutional powers following the radical change wrought to its composition by the introduction of proportional representation in 1949. Growing focus on broad analysis of the Senate’s constitutional potential rather than on the apparent minutiae of the standing orders is, therefore, not surprising.

There were at least two more attempts to compile editions of annotated standing orders. While he was Clerk, Rupert Loof produced a consolidated version of rulings of the President from 1903 to 1960 with a new index.[9] In the Preface to the work, dated 30 September 1963, he mentioned that a comprehensive set of standing orders showing alterations and additions since 1903, and renumbering, was in preparation but no further trace of that work has been found.[10] Another attempt is mentioned in the department’s second annual report, in 1983–84, as a Bicentenary Publications project being undertaken by the Table Office. It was proposed to trace the history and development of the standing orders since their adoption by the Senate in 1903.[11] After initial work on copying and indexing the 1903 debates, the project appears to have stalled although, as with the 1938 MS, the work done in indexing the 1903 debates has been used extensively in the preparation of this volume. Possible reasons for the discontinuation of the project include the increase in the size of the Senate in 1984, from 64 to 76, and the consequently greater demand on the advisory and support services of the department. Associated factors include the focus on planning for the new building, particularly the information systems required to support the operations of the Table Office, and the development of a revised set of standing orders which closely followed the move to the new Parliament House in 1988. Any of these factors could have diverted effort from the project which is not mentioned again in the department’s annals. It may simply have been a case of underestimating the scale of the project and overestimating the capacity of the office to manage it as an adjunct to its ‘normal’ work.

Early history: 1901–1903

Extensive deliberations on the nature and detail of its standing orders provided an early demonstration of the Senate’s institutional character and independence. Along with landmark debates on the first Supply Bill in 1901, the Customs Tariff Bill in 1902 and the Sugar Bounty Bill[12] in 1903, the debates on the standing orders showed the Senate asserting its place as a coequal partner in the national parliament. Others have told the story of these early years, including how the Senate rejected the draft standing orders prepared by its first Clerk, the anglophile E.G. Blackmore, in favour of adopting, as a temporary measure, the standing orders of the South Australian House of Assembly with which the greatest number of senators, including the President, was familiar.[13] These were the standing orders that had been used for the Federal Convention, to which Blackmore had been Clerk. Blackmore, in consultation with the first Prime Minister, Sir Edmund Barton, had also drafted standing orders for the House of Representatives while its first Clerk, George Jenkins, took on responsibility for organising the ceremonies in Melbourne for the opening of the first Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia. While Blackmore’s draft for the House was adopted (albeit on a temporary basis—till 1950) the Senate commissioned a standing orders committee to go away and devise a set of rules more appropriate to the needs of the new institution. By great fortune, the Senate had chosen as its first President Sir Richard Baker who had been President of the South Australian Legislative Council and a significant contributor to the constitutional conventions. His penetrating insight into the functions and purpose of the Senate under the Constitution and his driving role in developing the standing orders ensured that the heavy Westminster bias of Blackmore was considerably offset.[14]

Two drafts of Blackmore’s standing orders were tabled in 1901[15] and a motion was moved by the Government on 5 June 1901 to adopt on a temporary basis the second of those drafts, which had been modified by Senator Richard O’Connor (Prot, NSW), then Vice-President of the Executive Council (and later one of the first Justices of the High Court).[16] The motion was amended to provide instead for the establishment of a Standing Orders Committee to report to the Senate the following day on which State Parliament’s standing orders should be adopted instead, pending the preparation of the Senate’s own rules.[17] The committee was then appointed and consisted of the President, the Chairman of Committees (Senator Best from 28 June), and Senators O’Connor, Gould (FT, NSW), Downer (Prot, SA), Zeal (Prot, Vic), Dobson (FT, Tas), Higgs (ALP, Qld) and Harney (FT, WA).[18]

Over eleven meetings, the Standing Orders Committee, chaired by President Baker, thoroughly considered and restructured Blackmore’s draft and made extensive revisions, often substituting or inserting entirely new provisions. The committee reported to the Senate on 9 October 1901, including in its report detailed minutes in the style of committee of the whole deliberations on a bill and, most importantly, a draft of the proposed standing orders.[19]

A memorandum of the chairman included in the report set out the rationale for, and objects of, the committee’s recommendations. It is worth quoting at length:

In framing the Standing Orders the object of the Committee has been—

1st To embody in the Standing Orders the meaning and spirit of the Constitution so far as practice, procedure, and the relationship between the two Houses are concerned.

2nd To carry into effect the resolutions and what the Committee conceived to be the opinions of the Senate. [This was followed by a list of cases where such resolutions and opinions were given effect, and one case where an alternative was proposed instead.]

3rd The re-arrangement of the original Draft Standing Orders, so as to group under the headings of each chapter all the Standing Orders covered by the heading.

4th The formulation into Standing Orders of what has been the universal practice in the State Parliaments, so as to contain in the Standing Orders themselves, so far as possible, a complete code of procedure.

5th Simplification of procedure, and abolition of procedure and practices (based on obsolete conditions) which have now no effect or significance.

6th To provide that the Standing Orders of the Senate and of the House of Representatives shall be identical, except in those cases where difference cannot be avoided.

Reid and Forrest give an excellent account of the 1903 debates on the standing orders which occurred from 10–18 June and 12–19 August, including the crucial role played by President Baker in steering the Senate away from slavish obeisance to the House of Commons in Westminster.[20] In the midst of the two periods of intense debate, the Standing Orders Committee had presented another report recommending the reinstatement of the standing order that Blackmore had first proposed to open the collection:

In all cases not provided for hereinafter, or by Sessional or other Orders, resort shall be had to the rules, forms, and practices of the Commons House of the Imperial Parliament of Great Britain and Ireland in force on the 1st day of January, 1901, which shall be followed as far as they can be applied to the proceedings of the Senate.[21]

Though he chaired the committee and felt obliged to report the majority position,[22] Baker himself opposed the formalisation of ties with Westminster, preferring the Senate to establish practices and procedures of its own to suit its own constitutional position and circumstances. A majority of the Senate agreed with him and rejected the ‘umbilical’ standing order.

Having undergone intense scrutiny, the standing orders were finally adopted on 19 August 1903, with effect from 1 September that year. The first edition was a slim foolscap volume, printed by the Victorian Government Printer.

The following year, Baker articulated the mechanism by which the Senate would establish its procedural independence, in a paper entitled ‘Remarks and Suggestions on the Standing Orders’, tabled on 9 March 1904 and referred to the Standing Orders Committee.[23] He rationalised the omission of the umbilical standing order on the grounds that ‘in cases not positively and specifically provided for we should gradually build up ‘rules, forms, and practices’ of our own, suited to our own conditions.’ He made the following suggestions:

(1) That in any case which may arise which has not been provided for by the rules, or in which the rules appear insufficient or manifestly inconvenient, the President should state to the Senate (after mature consideration, if possible) what, in his opinion, is the best procedure to adopt, and that the Senate should decide.

(2) That at the commencement of each session the President should lay a paper on the Table formulating and tabulating all the decisions arrived at during the last session, giving reasons (if it should be necessary to do so) why, in his opinion, any of his own decisions were incorrect, or any of the decisions of the Senate would lead to inconvenient results. The Senate could then take the decisions objected to into consideration and decide the matter.

These suggestions were adopted by the Senate with the qualification, in relation to paragraph (1), that if no objection was raised, the rule stated by the President would prevail until altered by the Senate.[24] The President’s first report to the Standing Orders Committee under paragraph (2) was tabled on 17 August 1905.[25] From 1910, in accordance with a resolution of the Standing Orders Committee on 23 November that year, indexed rulings of Presidents were published following completion of their term of office.[26] Presidents’ rulings continue to be an important source of guidance to the Senate in dealing with procedural questions that are either new or, because of changing circumstances, require a new solution. From the beginning, Presidents, in making rulings, have leaned towards the interpretation which preserves or strengthens the powers of the Senate and the rights of senators.[27]

Second edition–1909

President Baker made a significant number of rulings in the early years to elucidate the practices of the Senate, but changes in those practices began almost immediately. Eventually, these would be reflected in amendments to the standing orders. For example, a resolution of the Senate on 7 October 1903 exempted the adjournment debate from the normal rule of relevance but it would take another two years before the Senate adopted a Standing Orders Committee recommendation to amend the relevant standing order accordingly.[28]

Another important early development came in 1905 when the Standing Orders Committee recommended the adoption of a standing order providing for instructions to be given to committees of the whole to expand their powers to amend bills by allowing (on amending bills) amendments to be moved to the parent Act that were not relevant to the subject matter of the bill.[29] This was a significant expansion of powers in the days when the statute book was much smaller and amending bills were more narrowly cast. These days it is rare that an amending bill is so narrowly drawn that a proposed amendment to the parent Act cannot be made relevant to the subject matter of the bill but, at the time, this was a significant statement of the scope of the Senate’s legislative interests and powers.

In December 1906 a referendum to change the commencement date for senators’ terms under s.13 of the Constitution was carried by the required majorities. Terms that had begun on 1 January would now begin on 1 July and this change in timing affected arrangements for the terms of office of the President and Deputy President and some of the assumptions behind procedures for the opening of Parliament. The Standing Orders Committee had been stockpiling a variety of issues and in October 1908 presented a report recommending multiple amendments and alterations, including as a consequence of the referendum. The report lay dormant till the following year but on 9 and 10 September 1909 the proposed changes were extensively debated in the very useful committee of the whole forum which allowed senators to make multiple contributions and argue the toss on the merits of the proposals and any alternatives.[30]

The changes made were wide-ranging and included several clarifications of, and additions to, legislation procedures, and the adoption of new standing orders on, among other things, the recording in the Journals of senators’ attendance (for the purpose of s.20 of the Constitution), the recording of senators’ names after a count-out, and the process for determining points of order. The changes agreed to were so extensive that at the end of the debate on 10 September, a complete reprint was ordered of the whole standing orders, together with a fresh index—rather than the usual loose leaflets of amendments to be slipped or pasted into the existing volume.[31]

Third edition–1922

Before the next full reprint in 1922, the Senate had adopted new standing orders on a number of topics including the interruption of business, the requirement for a senator’s recorded vote to accord with his voice vote, the prohibition on standing committees meeting during sittings of the Senate, time limits on speeches and the designation of certain business as ‘Business of the Senate’ taking precedence over government and general business.[32] This last standing order brought together a number of matters given precedence under other standing orders or by virtue of rulings of the President.[33] These were matters that were identified as so important to the Senate as a whole that they warranted precedence above the business of the executive government.

The Senate had adopted time limits on individual speeches in 1919 following determined efforts by senators to delay the passage of the Commonwealth Electoral Bill the previous year. These efforts included an all-night speech by Opposition Leader Senator Albert Gardiner (ALP, NSW), during which he read the entire bill aloud and, as his stamina flagged, was occasionally allowed by the chair to speak while seated.[34] On the night of 25 and 26 November 1920, Senator Gardiner was again to be found testing the limits of the new restrictions on debate in committee of the whole, during consideration of the War Precautions Act Repeal Bill. Senator Wilson (Nat, SA) moved the rarely used ‘gag’ (in the old form ‘That the Committee do now divide’). It does not seem to have been an attempt by an impatient government to shut down debate. Senator Wilson was not at that time the honorary minister he would become just over two years later. From a distant perspective, it looks like an episode of determined obstruction by a minority which stretched far into the night and tried the patience of the majority, the vote on the gag being carried by 20 votes to 3.[35]

Fourth edition–1937

In the sessions of 1923–24 and 1925 the use of the gag by government senators became more common, including in association with all-night or weekend sittings when tempers were most likely to fray. In debate on the Appropriation Bill 1923–24, for example, which occurred through the night of 22–23 August 1923, the gag was moved eight times and once more on the Income Tax Assessment Bill [No. 2] which followed it. The gag was also used the following day on the River Murray Waters Bill.[36] In July 1925, the gag was moved 6 times on the Immigration Bill and in August, in relation to the Peace Officers Bill, considered on a Saturday and continuing the following Monday, the gag was moved 21 times.[37]

The gag is a crude device to truncate debate. If a gag motion is agreed to, the main question is required to be put without further debate. While it may have some efficacy for dealing with a single question, it is an ineffective means of dealing with bills to which there may be many proposed amendments and therefore many questions to be determined. After 21 gag motions were required during consideration of the Peace Officers Bill in 1925, the Senate referred to the Standing Orders Committee the formulation of additional standing orders to provide for the limitation of debate on bills declared as urgent bills, otherwise known as a ‘guillotine’.[38] The Senate divided on the motion which was carried by 17 votes to 8, Senator Gardiner being amongst those voting ‘No’. When the Standing Orders Committee report was debated on 3 March 1926, the Leader of the Government, Senator Pearce (Nat, WA), rationalised the guillotine as a more just device than the gag in the following terms:

… if an active minority desires to block the passage of a measure, which it knows the majority wishes to pass, it can occupy practically the whole time allowed for debate, and the only weapon in the hands of the Government is the ‘gag’, by which the mouths of its own supporters are shut, and the whole field of debate is in the hands of those who are opposed to the measure. Under the guillotine provision a reasonable time is allowed for the discussion of a bill or motion, and, that time having been fixed, each side alternately can put forward its speakers, and all aspects of the matter can be debated. This is fair to the majority as well as to the minority. It is much fairer than the application of the ‘gag’, which often excludes useful contributions, and permits what is practically a waste of time by honourable senators who merely talk against time.[39]

Senator Gardiner spoke against the adoption of the guillotine, referring to his own role in delaying the Peace Officers Bill, but the motion was carried by 20 votes to 7 and the guillotine became part of the Senate’s procedures, just as it was part of the procedures in much larger houses such as the House of Commons and the House of Representatives.[40]

Of major significance for the future role of the Senate was the establishment, in December 1929, of a select committee to inquire into the advisability or otherwise of having standing committees in a number of areas in order to improve the legislative work of the Senate and increase the participation of senators in such work. The areas in which it was envisaged that committees might be established included statutory rules and ordinances, international relations, finance, and private members’ bills. When the select committee initially recommended the creation of committees in the first two areas, as well as adjustments to standing orders to facilitate the referral of bills to committees, it was instructed to reconsider.[41] The committee’s second report dropped the recommendation for a Standing Committee on External Affairs, which had apparently made the Government nervous, and the remaining recommendations were adopted on 14 May 1931.[42] They were then referred to the Standing Orders Committee for translation into appropriate new standing orders and amendments which were adopted on 11 March 1932.[43]

This was an historic day for the Senate with the establishment of the Standing Committee on Regulations and Ordinances, which has subsequently scrutinised all newly made delegated legislation to ensure its compliance with fundamental standards of civil society. Moreover, the framework was laid down for the future establishment of other standing committees and the referral of bills to standing or select committees. Although it would be decades before the creation of a system of standing committees and the commencement of regular and routine referrals of bills to them, the means to do so were there in the standing orders from 1932. Gradually, over time, these ideas would be fully realised.

The debate on the establishment of the Regulations and Ordinances Committee was not without controversy, and Senators Rae (Lang Lab, NSW) and Dunn (Lang Lab, NSW) were both suspended on 4 March 1932 for defiance of the chair.[44] These two senators were also indirectly responsible for the next set of amendments recommended by the Standing Orders Committee. In August 1932, after senators chosen at the half-Senate election of December 1931 were sworn in, the Senate proceeded to elect a new President. When there is no President, the Clerk acts as chairman of the Senate. On this occasion, the Clerk, George Monahan, was required to rule on a point of order taken by Senator Pearce that Senator Dunn’s speech in support of his nomination of Senator Rae for the presidency was not relevant. The Clerk upheld the point of order. Senator Dunn then moved a motion of dissent from Monahan’s ruling and during the debate, the powers of the Clerk in this situation were queried. After some awkward manoeuvres, Senator Dunn’s motion of dissent was lost, Senator Lynch (Nat, WA) was elected President by a comfortable majority and the question of the Clerk’s powers was referred to the Standing Orders Committee. When that committee reported, it recommended that the relevant standing order be amended to specify that the Clerk has all the powers of President under the standing orders when presiding over the election of a new President.[45]

In the same report, the Standing Orders Committee also proposed a new standing order to provide for the consideration or adoption of committee reports to have precedence over other General Business on certain days.[46] This change allowed the reports of the important new Regulations and Ordinances Committee to receive appropriate attention. The new procedures for referral of bills were redrafted to enhance their clarity and the old forms of the ‘gag’ motion (‘That the Senate [or committee] do now divide’) were replaced with the current form (‘That the question be now put’).

The final set of amendments preceding the 1937 edition were mostly housekeeping matters, occasioned by the pressing need for a reprint ‘owing to depletion of stock copies’.[47]

The 1938 MS–a clerkly treasure

From 1903 until 1937 the standing orders had been the subject of regular scrutiny and amendment, often vigorously contested. Some significant alterations and additions had been made. Recording and supporting the work of the Standing Orders Committee were the four Clerks of the Senate who had held office during that time: E.G. Blackmore, Charles Boydell, Charles Gavan Duffy and George Monahan. The Clerks were supported by a small number of other senior officers, including the Clerk Assistant, the Usher of the Black Rod and Clerk of Committees (a combined role that from time to time, along with the Clerk Assistant, also took on the duties of Secretary to the Joint House Department), and the Clerk of Records and Papers.[48] In 1937, these positions were occupied, respectively, by Robert Broinowski, John Edwards and Rupert Loof, all to become Clerk in turn.[49]

Which of these men was responsible for assembling what I have called the 1938 MS?[50] Whoever it was had a comprehensive knowledge of the standing orders and their history, a command of the rulings of the President, a high level ability to question the rationale behind the rules, practical experience of committees, and a mind for detail, including the practical impact of particular standing orders on chamber operations. He (for it was, of course, a he) also had a neat, regular hand, somewhat—but not entirely—lacking in distinguishing characteristics.[51] Monahan had 18 years’ experience as Clerk and secretary to the Standing Orders Committee, and had worked for the Senate Department since 1901. As his evidence to the Select Committee on the Standing Committee System shows, Monahan had a profound and mature understanding of parliamentary operations, but Monahan retired in 1938 well before the work was completed. Less is known of Broinowski’s procedural achievements but he also retired before work on the typescript ceased. Both Edwards and Loof are potential candidates. Appendix 12 contains an assessment of the evidence of authorship which overwhelmingly points to Edwards.

The 1938 MS was a prodigious endeavour and is a precious legacy from that time. Some part of Edwards’ scholarship is preserved in this work which makes frequent reference to and use of it.

The barren years and the fifth edition–1966

After the 1937 edition was reprinted, the Standing Orders Committee made one further report to the Senate recommending some minor amendments to the procedures for urgency motions. Presented in October 1938, the report was considered shortly afterwards but was referred back to the committee for further examination.[52] It never re-emerged. At the end of the year, the long-serving Monahan retired to be replaced as Clerk by Robert Broinowski. World events would soon eclipse everything.

During the War, the committee met once, in 1943, to discuss the standing order prohibiting the reading of speeches. The chair of the committee, President Cunningham, made a statement to the Senate conveying the committee’s view that the standing order should remain as it was but ‘that if a Senator desires for special reasons to read his speech, he should be able to do so by leave of the Senate.’ The President indicated that he would rule accordingly.[53]

The Standing Orders Committee did not meet again for ten years until, in 1953, the impending visit of Queen Elizabeth II prompted a quick amendment to the procedures for the opening of Parliament to accommodate the presence of the sovereign herself, rather than the Governor-General as her representative.[54] It was the first visit to Australia by a reigning monarch and the government took the opportunity to arrange for the Parliament to be prorogued on 4 February 1954 until 15 February, to allow for a state opening by the Queen. The necessary amendments were adopted without debate in the October preceding the Royal visit. The President, Clerk and Black Rod had new robes and furbelows for the occasion,[55] but for all his painstaking work on the 1938 MS and the momentous changes to the Senate in 1949, John Edwards’ impact on the standing orders as Clerk of the Senate from 1942 to 1955 was minimal.

His successor, Rupert Loof, fared little better. The Standing Orders Committee began to meet again on a more regular basis from 1959 to consider whether any changes were required to the standing orders as a consequence of, among other things, the enlargement of the Senate in 1949. Another spur was provided by an adjournment speech made by Senator Willesee (ALP, WA) on 30 April 1959 in which he called for consideration of amendments to several standing orders. Senators were invited to submit any suggestions for amendment or review of particular standing orders. The review dragged on and a subcommittee was formed in 1963 to make recommendations on which changes should proceed. An issue raised by the Regulations and Ordinances Committee as to whether regulations and ordinances of the Northern Territory and Territory of Papua and New Guinea should be excluded from that committee’s purview also delayed the finalisation of the review.[56] The committee eventually reported after Loof had retired, recommending a variety of non-controversial amendments. Most of them were of minor or practical significance only, apart from the establishment of a standing committee of privileges, the incorporation of rules for questions and the exclusion of certain territory regulations and ordinances from referral to the Regulations and Ordinances Committee. The recommendations were adopted on 2 December 1965 and the fifth edition of the standing orders came into operation on 1 January 1966.

The impact of proportional representation

The achievements of the early Senate in severing the umbilical cord to Westminster and robustly questioning its modus operandi over its first decades had largely faded by the outbreak of World War II, although the institution was not entirely supine.[57] When the Senate began to rediscover legislative activism from the late 1950s, the standing orders themselves were often not the vehicle for change. A perception had grown up that the standing orders were like the tablets of Moses and should not be interfered with. It was perceptions like these that fostered such practices, for example, as the routine suspension of standing orders to enable bills to be dealt with more expeditiously rather than over a number of days as prescribed in the standing orders. These aberrant practices persisted for decades before a sessional order that reflected actual practice was finally adopted in 1987.[58] Until the 1990s, many of the most significant procedural changes were effected by resolution or sessional order and made it into the standing orders (if at all) only after a significant period of time had elapsed.

The level of interest in maintaining the standing orders should not be regarded as an indicator of the health of the institution. On the contrary, the institution was beginning to hum. Many years later, a former Clerk of the Senate would recall the effect of proportional representation on the Senate in the following terms: ‘In 1955 it was very obvious that the Senate had received not just a blood transfusion but a heart transplant.’[59] From the mid-1950s significant changes were taking place. Important stances were being taken, for example, on the Senate’s constitutional position regarding appropriation bills for the ordinary annual services of the government.[60] New accountability measures were being tried, such as the examination of estimates of expenditure in committee of the whole before the receipt of the Appropriation Bills from the House (giving the Senate much more time to conduct its scrutiny of the government’s expenditure proposals).[61] After a period of desuetude, select committees were again being employed to inquire into matters of public policy and administration.[62] Parliamentary officers were active in studying, and bringing to the attention of senators, the operation of committees in other jurisdictions.[63] But caution was still the order of the day. When debating Odgers’ report on his American travels, Opposition Leader Senator McKenna (ALP, Tas) praised his efforts but urged patience:

I know that he has a burning ambition to see the Senate play a major role in this Parliament. I merely say to him that, whilst he must not despair, he must be patient. Speaking from an experience of politics extending over a considerable time, I know that it takes at least five years to secure the acceptance of a new idea.[64]

It would take a lot more than five years for Odgers’ vision to be realised.

The committee system and the 1970s

The momentous events that culminated on the evening of 11 June 1970 in the establishment of seven legislative and general purpose standing committees and five estimates committees did not originate in a specific recommendation of the Standing Orders Committee. Although the committee had been considering a standing committee system from 1967 and had commissioned the Clerk, Jim Odgers, to prepare a report on the subject which he presented in three parts in November 1969 and in January and March 1970, the committee refrained from making any recommendations and submitted Odgers’ reports to the Senate without comment.[65] Part 1 considered the establishment of six specialist watchdog committees on Statutory Corporations, Science and Technology, Petitions, Broadcasting and Television, Narcotics, and National Publicity and Public Relations. Part 2 considered the establishment of six legislative and general purpose standing committees to cover the activities of all departments of state as follows: External Affairs and Defence; Transport and Communications; Trade, Industry and Labour; Legal, Constitutional and Home Affairs; Health, Welfare, Educations and Science; and National Finance and Development. Part 3 provided some additional material and recommended support for a committee on Statutory Corporations and the six legislative and general purpose standing committees listed previously.

There were three proposals before the Senate on the night of 11 June 1970: a proposal for seven legislative and general purpose standing committees from the Leader of the Opposition, Senator Murphy (ALP, NSW); a proposal for five estimates committees from the Leader of the Government, Senator Anderson (Lib, NSW); and a proposal for six legislative and general purpose standing committees and a committee on statutory corporations, to be set up gradually over a period of 12 months, from the Leader of the Australian Democratic Labor Party, Senator Gair (DLP, Qld). All had been moved and debated concurrently during general business on Thursday, 4 June 1970, and the debate was resumed a week later. When it came to the vote, Senator Murphy’s motion was agreed to by 27 votes to 26 with Independent Senator Turnbull (Tas) and Liberal Senator Wood (Qld) supporting the ALP against the combined forces of the Coalition and the DLP. Senator Anderson’s motion was agreed to by 26 votes to 25, Senators Turnbull and Wood absenting themselves from the vote. Finally, Senator Gair’s motion was defeated on an equally divided vote with Senator Wood voting with the ALP and Senator Turnbull not voting. Senator Wood explained that he was opposing the motion because it effectively duplicated Senator Murphy’s proposal which had already been agreed to.[66]

A full account of the events leading to the establishment of the Senate committee system is given in the 6th edition of Australian Senate Practice.[67] All parties supported a policy of gradualism in implementing the new system. Time was taken to debate fully such important matters as the membership formulae for the committees, only two of which were established initially as a trial.[68] Membership would accommodate all the groupings in the Senate—government, opposition, and minority groups and independents—but all committees would have government chairs by ‘long-standing convention’.[69] The new committees were not permitted to meet during the sitting of the Senate except by order.[70] The importance of these new committees was recognised, however, in a new provision for notices of motion for the reference of matters to the committees to be able to be given at any time when there was no other business before the chair, or to be handed to the Clerk. Moreover, such notices would have precedence as business of the Senate, ahead of government and general business.[71]

The first two committees to be established were the Standing Committee on Health and Welfare and the Standing Committee on Primary and Secondary Industry and Trade. In a remarkable reflection of the first inquiry undertaken by a Senate committee in 1901,[72] the latter committee’s first report was on Freight Rates on Australian National Line Shipping Services to and from Tasmania.[73] The Health and Welfare Committee’s Report on Mentally and Physically Handicapped Persons in Australia, presented in May 1971,[74] was the first report from the new category of committee and the forerunner of many groundbreaking inquiries on matters of national policy significance. Estimates committees received their first reference of particulars of proposed expenditure on 17 September 1970, for report by 13 October 1970.[75] The five committees met over 7 days for a total of 74 hours and eventually reported on 26 and 28 October, having received an open-ended extension.[76]

Meanwhile, President McMullin presented a report in February 1971 pursuant to the resolutions of 11 June 1970 and 19 August 1970 establishing the committees. The report noted developments in other jurisdictions and concluded that the Senate’s committee system was now in good company. It noted that estimates committees had been established separately but that it would be up to a future Senate to consider whether the estimates function should ultimately be embraced by the legislative and general purpose standing committees.[77] Suggested operating procedures for estimates committees, circulated by the Leader of the Government in the Senate but not formally adopted by the Senate, were included in the report.[78] The list contains many items that remain familiar to observers of estimates hearings today, including:

- a restriction on no more than three (now four) committees meeting at once because of the constraints on Hansard and the Government Printer in supporting simultaneous meetings;[79]

- the attendance of Senate ministers, preferably throughout the hearings but certainly at the beginning of each department to give any opening statement and answer questions, and also if specifically requested by members of the committee;

- questions involving opinions on matters of policy to be directed to ministers, not officers (now in Privilege Resolution (1)(16));

- the practices and procedures of the Senate to be followed as far as possible;

- reports to be brief and accompanied by minutes of proceedings and the Hansard transcript of the evidence, and political comment to be left to debate on the appropriation bills (the primary function of estimates being the seeking of information).[80]

Other aspects of the suggested procedures were not implemented, including the adoption of committee of the whole practices in confining senators to 15 minutes each at any one time. The choice of appropriate officers was left to ministers in the absence of specific powers to call witnesses. This is still largely the case in practice despite the extension of inquiry powers in 1994 to committees examining estimates.

Though still at an experimental stage, the estimates process was judged as a success.[81] Likewise, the legislative and general purpose committees were judged to be doing important work and the report supported the further expansion in the number of these committees operating. It was envisaged that public hearings might one day be televised to further stimulate the growth of public interest and participation in the new committee system.[82]

While committees have gone from strength to strength, there have also been some distractions in the form of occasional proposals to change the nature of the system. An attempt to establish a system of joint committees in the mid 1970s and a second attempt following the 1987 double dissolution are described in more detail in the commentary on SO 25.

The impact of the committee system on the Senate cannot be overestimated. Already, by the time the President made his report in February 1971, debate was judged to be more penetrating because of the specialised knowledge senators were acquiring from committee inquiries. At a retrospective conference on the twentieth anniversary of the committee system in 1990, it was apparent that committee work had transformed the careers of senators. It was a far cry from the situation recounted by former Senator Davidson (Lib, SA) who recalled being told of Menzies’ opposition to Senate select committees in the 1960s: ‘ “Backbench Senators” ’, Menzies was reported to have said, ‘will have access to matters not meant for them and to material which is inappropriate for their role in Parliament.’[83]

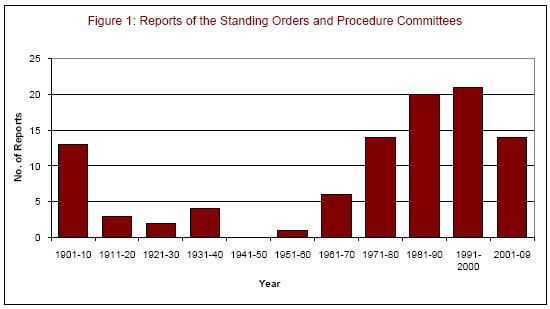

Committee work gave senators a greater stake in the institution as well as access to previously unimaginable levels of information. One sign of their engagement was in the resuscitation of the Standing Orders Committee from the later 1960s onwards. Figure 1 gives an indication of the resurgence in activity from that time and Appendix 9 reveals the incidence of reports on such committee-related topics as the disclosure of unpublished evidence, committees meeting after dissolution of the House of Representatives, presentation of committee reports out of sitting, rights of witnesses, questions to committee chairs, staffing arrangements and televising of hearings. There is also no doubt that Odgers, now Clerk, worked away quietly in the background, hanging onto his dream of a committee system and encouraging senators in their select committee work.

Standing Orders Committee reports were extensively debated throughout the 1970s and up to 1983, sometimes frustratingly so as similar territory was traversed at length, often with little apparent result. Senators of the old school like Senators Cavanagh (ALP, SA), Poyser (ALP, Vic) and Wright (Lib, Ind from 1978, Tas) thundered against restrictions on the rights of individual senators. Rationalists like Senator Murphy pleaded for procedures that could be explained to the man in the street without appearing ridiculous.[84] At root, however, was a re-engagement by senators with their procedures to an extent not seen since the first decade of the twentieth century.

The result was the publication of two new editions of standing orders in 1972 and 1977, the sixth and seventh editions and the last before Odgers retired as Clerk in 1979. The 1972 edition included changes to the size of the Standing Orders Committee, the reconstitution of the Printing Committee as the Publications Committee, clarification of the form of the question in committee of the whole when dealing with requests for amendments, time limits on speeches and the publication of committee evidence and documents. New to the 1977 edition were changes to the duration of the bells arising from building extensions, the facility to ask questions of committee chairs,[85] a new form of urgency motion, expedition of bills received from the House of Representatives, procedures for questions on notice and answers thereto, clerical amendments to tabled and printed papers[86] and, most significantly, the adoption of permanent orders for the legislative and general purpose standing committees and estimates committees.

A new order: the case for change

Two further editions, the eighth and ninth, were produced in 1981, during the clerkship of Keith Bradshaw. These were the last before the major revision at the end of that decade. They included such matters as changes to the composition of the Standing Orders Committee to include the Government and Opposition leaders as ex officio members, the inclusion of minority groups in the membership formulae for legislative and general purpose and estimates committees, the re-expression of the terms of reference for the Regulations and Ordinances Committee and consequent changes to the formulation of what constitutes business of the Senate, and the re-expression of the rule about commencing new business after a certain point in the day (April 1981 edition). A second edition in the same year was necessitated by a change to the title of the office of Chairman of Committees to ‘Deputy President and Chairman of Committees’, and the abolition of the requirement for motions to be seconded, changes which affected numerous standing orders. The new procedures for urgency motions and discussion of matters of public importance were also incorporated into the standing orders. There were also some deletions of superfluous or defunct standing orders but, in the November 1981 reprint, care was taken to preserve the existing numbering, not least to avoid rendering the 5th edition of Australian Senate Practice (1976) obsolete.

Between 1981 and 1987 there were no changes made to the standing orders but there was a great deal of innovative thought applied to procedural matters and to the broader constitutional context in which the Senate operated. Indeed, Standing Orders Committee reports between 1983 and 1987 were largely ignored and the committee expressed dissatisfaction with this state of affairs in its Fourth Report of the Sixty-Second Session and presented a list of outstanding recommendations.[87] Debate on the report began in February 1987 but was not concluded before the double dissolution that year.[88]

The first major issue to receive attention during the 1980s was the financial position of the Parliament in relation to the Executive. The Senate Select Committee on Parliament’s Appropriations and Staffing reported in June 1981 recommending a range of reforms including:

- the establishment of an Appropriations and Staffing Committee to determine the estimates for the Senate and to confer with a similar committee of the House of Representatives as required;

- a separate parliamentary appropriation bill, also providing for an Advance to the President of the Senate on the same basis as the Advance to the Minister for Finance;

- amendment of the then Public Service Act 1922 to provide the Presiding Officers with powers of appointment, promotion, creation, abolition and re-classification of positions and the power to determine terms and conditions of service.

The establishment of the select committee owes much to the work of former Clerk, Roy Bullock, who, in 1971 at the request of the then President, Senator Sir Magnus Cormack, had written a paper on proposals to secure greater control by the Parliament over the appropriation of money for parliamentary services.[89] The creation of the Appropriations and Staffing Committee (see SO 19) and the introduction of a separate bill for parliamentary appropriations occurred the following year, while changes occurred to the employment framework over the next few years that finally halted the practice of all employment decisions for the Senate Department being made by the Governor-General-in-Council. Full autonomy in staffing finally occurred with the passage of the Parliamentary Service Act 1999, when the Clerk acquired the statutory function of employer of all departmental staff.

Major developments in parliamentary privilege also occurred. In 1982 a joint select committee was established to examine any changes considered desirable to the law and practice of parliamentary privilege, to procedures for raising, investigating and determining allegations of contempt and to penalties for contempt. The committee’s work was wide-ranging and it presented a final report in October 1984, having tabled an exposure draft of the report in June that year.[90] Section 49 of the Constitution provided for the powers, privileges and immunities of the Houses and their committees to be the same as those of the United Kingdom House of Commons at the time of the adoption of the Constitution until declared by the Parliament to be otherwise. There had been no such general declaration but the report of the joint select committee provided a basis for work to begin on the partial codification of the law of parliamentary privilege.

The real trigger, however, for the Parliamentary Privileges Bill 1987 was provided by two adverse court judgments in NSW in 1985 and 1986 in the case of R v Murphy which had the effect of allowing witnesses in court to be questioned about their evidence, including in camera evidence, before parliamentary committees.[91] By declaring the scope of the term ‘proceedings in Parliament’ the Act rendered unlawful such uses of committee evidence, among other things. It was followed in 1988 by a series of resolutions in the Senate giving effect to important principles of parliamentary privilege that did not require, or were unsuitable for, statutory expression.[92] These included codes for the protection of witnesses before Senate committees in general and the Privileges Committee in particular, a non-exhaustive list of matters constituting contempts, procedures for raising and determining matters of privilege, and the pioneering procedures for persons adversely affected by references to them in the Senate to have recourse to a right of reply.

A third, highly significant committee inquiry was undertaken by the Senate Select Committee on Legislation Procedures in 1988. Its aim was to devise procedures to facilitate the referral of bills to committees on a more systematic basis and to expedite the consideration of bills by the Senate. The committee also looked at allocating one day each week for committee consideration of bills and at ways in which the end of sitting concentration of bills could be avoided. [93]

Procedures for the referral of bills to committees had long been available to the Senate but practice had never caught up with the often-expressed desire for greater committee involvement, going back at least as far as the 1929 select committee on the advisability of establishing standing committees for various purposes, including the examination of bills.[94] What the 1988 select committee developed was a mechanism to achieve the referral of bills on a regular basis. It recommended the establishment of a Selection of Bills Committee which would comprise the whips of parties represented in the Senate and four other senators who would meet regularly to examine bills introduced into the Parliament with a view to making recommendations as to whether a bill should be referred, at what stage, to which committee and for how long. There was no formal prescription as to how committees should deal with the bills so referred. They might choose to follow committee of the whole-style procedures and go through the bill in private session, considering whether to recommend amendments. On the other hand, they might choose to subject the bill to a full public inquiry by seeking submissions on it and taking evidence from a range of witnesses before reporting back to the Senate with any recommendations. In practice, the latter approach has been the more common.

The select committee’s recommendations were adopted on 5 December 1989 and finally came into effect, after some modifications, in August 1990.[95]

In the meantime, the 1980s was a time of experimentation with the adoption of a variety of sessional orders trying out new routines of business,[96] expedited proceedings on all bills,[97] greater opportunities for debating government documents, committee reports and government responses to committee reports,[98] and the referral of annual reports to committees.[99] These are evidence of a push towards more rational procedures and more opportunities for the Senate to exercise its accountability function. Senators of the day including Senators Macklin (AD, Qld), Vigor (AD, SA) and Hamer (Lib, Vic) came up with innovative ideas, including the first versions of the bills cut-off order.[100]

In commenting on one of the first uses of the new expedited proceedings on bills, Senator Gareth Evans (ALP, Vic) commented that they were ‘designed to get rid of mumbo-jumbo’.[101] Behind the scenes, another Evans—Harry Evans, then Clerk Assistant (Procedure)—was also working towards greater rationality in proceedings and the professional development of a growing number of Senate staff. Harry Evans was directly involved in the development of the Parliamentary Privileges Act 1987 and the 1988 resolutions, having been the principal critic of the NSW judgments, as well as Senate adviser to the Joint Select Committee on Parliamentary Privilege. In February 1985 he started the Procedural Information Bulletin as a means of disseminating to staff information about procedural developments in the Senate and its committees.[102] His efforts would culminate in the first major revision of the standing orders since their adoption in 1903.

The 1989 revision[103]

The 1989 revision really began at the end of 1986. If a single catalyst for the revision can be identified, it was in the proceedings on the Australia Card Bill 1986. On 10 December 1986 the necessary questions were put to determine the fate of a second reading amendment, prior to determining the question for the second reading of the bill. In those days, such amendments were determined in two stages, with the first question designed to establish whether there was support for removing words from the motion (proposed to be substituted by other words) before a second question ascertained whether there was support for the substitution. In the Senate, an equally divided or negatived vote on both questions would leave only the original ‘That’ standing, clearly a ridiculous and embarrassing situation. As Evans argued to his Clerk, Alan Cumming Thom:

In the proceedings on the Bill the Senate was again in the situation of having only the word ‘That’ left of the motion, the remainder of the words of the motion having been left out and the Senate having failed to agree to insert other words, an amendment to the words proposed to be inserted having been moved. This situation could have caused embarrassment to the non-government parties and to the Senate as an institution but it was avoided by the motion for the second reading of the Bill being put again by leave.[104]

Harry Evans argued that there was no good reason for not putting all amendments in one question, ‘That the amendment be agreed to.’[105] He identified the standing orders that would require deletion if the new practice were to be adopted[106] and also drafted the replacement orders.

At the same time, he made several other suggestions for procedures that could be rationalised and presented to senators as a comprehensive package. These included expedited proceedings for bills (already under consideration), streamlining of procedures for resuming interrupted debates (rather than having to move a motion for the resumption of the debate after each interruption), more liberal rules for giving notices, and putting the question on urgency motions at the expiration of time for the debate. Furthermore, there was a need to rationalise obsolete, superfluous and conflicting provisions and to modernise ambiguous and obscure language. A third problem was the conflict between standing orders and sessional orders that had been in force for many years. Clerks, Evans argued, should take the initiative in proposing changes, thus demonstrating their expertise and understanding as a source of advice, rather than cultivating what might now be called ‘secret clerks’ business’ by maintaining the standing orders as a subject of mystery and complexity that only clerks could interpret.

The proposals were put to the Standing Orders Committee in 1987 and work began on the revision. A first draft was tabled in the Senate on 17 May 1988, together with explanatory material and charts showing the correspondence between old and new numbering. Around 450 standing orders were reduced to just over 200, with some reorganisation of chapters and considerable modernisation of style. By this stage the old standing orders had become a shambles, overridden or modified by sessional orders, and having grown somewhat haphazardly since 1903. There were gaps in the numbering owing to earlier deletions. The archaic language and syntax of the standing orders detracted from their inherent value as sound rules of procedure. The move to a new building in 1988 also prompted some minor changes of a logistical nature.[107] The rationalisation transformed the Senate’s standing orders into a set of contemporary procedures for a modern parliamentary body with a focus on legislating and on holding the government of the day to account.

It was intended that the revised standing orders should be a codification and clarification of existing practice by incorporating long-standing sessional orders and by removing duplication and repetition, and provisions that had been made superfluous. Numerous proposed changes of substance were explained in notes that accompanied the draft, and the whole package was put before senators and the Procedure Committee (which had superseded the Standing Orders Committee in 1987) with a view to extensive consultations taking place on the form and substance of the changes.[108]

Consultations did occur over the next several months, primarily driven by the then Deputy President, Senator Hamer whose work was acknowledged in a statement by the President when tabling a revised draft on 1 November 1989, together with revised explanatory material which itemised the differences between the earlier and present drafts and the reasons for the changes.[109] A significant group of changes had been requested by senators and these included the restoration of some procedures that had been proposed for deletion on the grounds that they had been little used or considered outmoded. Procedures for a roll call (then known as a call of the Senate), the entitlement of backbench senators to retain their seats during their terms, the requirement for a senator nominated as President to express a sense of the honour proposed to be conferred on him or her, and the prohibition on moving more than once in 15 minutes motions in committee of the whole for the closure or to report progress were all restored at the request of senators following consultations. The suggestion for a new procedure that would allow the President to suspend the Senate in the absence of a quorum, rather than adjourning it, was also rejected. Further changes were made to give expression to procedural rules that had been implicit in rulings of the President.[110]

Unfortunately, it is not possible to consult the debate on the adoption of the new standing orders because there was none. The motion to adopt the revision and for the new standing orders to come into effect on the first sitting day in 1990 was dealt with as formal business on 21 November 1989 and therefore agreed to without amendment or debate.[111]

The 1990s and beyond: new frontiers

Not long afterwards, the Senate also agreed to a series of orders arising out of the Select Committee on Legislation Procedures for the referral of bills to committees and other matters (see above). These did not come into effect till the second half of 1990, at the same time as another major change occurred in the way the Senate would be seen by the world and perceived by itself. This change was, of course, the televising of parliament. Proceedings of both Houses had long been broadcast on radio by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation under the authority of the Parliamentary Proceedings Broadcasting Act 1946 which also established the Joint Committee on the Broadcasting of Parliamentary Proceedings. The committee’s role was to work out the general principles on which broadcasting should be allocated between the Houses and to determine the days on which each House should be broadcast. The committee also determined conditions for the re-broadcasting of proceedings. The Act applied only to radio broadcasting. In a resolution of 13 December 1988, the Senate permitted the broadcasting and re-broadcasting on television and radio of sound recordings of excerpts of its proceedings.[112]

Televising of Senate proceedings was initiated by an opposition senator, Senator Vanstone (Lib, SA) in 1990 and, again, its commencement was closely connected with the move to a new building which was equipped with the infrastructure necessary to provide television and radio coverage. Several reports on televising and radio broadcasting of both Houses and their committees had been presented in the latter half of the 1980s by the Joint Committee on Broadcasting of Parliamentary Proceedings but not implemented.[113] Senator Vanstone’s motion, moved after a suspension of standing orders, provided for the trial televising of Question Time in the Senate to commence in the August sittings of 1990.[114] The trial became permanent the following year and the House of Representatives also decided to televise its proceedings.

The impact of television and, later, webcasting, on Senate proceedings and their reception by the public is beyond the scope of this study. It is certainly the case, however, that the focus on Question Time as a spectacle and a performance has led to a distorted view of what Parliament actually does and a corresponding decline in respect for the institution.

The reductive effect of television has been considerably offset, in many respects, by the growth of Senate committee work and its consequent impact, made possible by the adoption of procedures for the systematic referral of bills to committees. The percentage of bills referred to committees during the 1990s averaged about 30 per cent of all bills passed by the Senate. During the 2000s to date, this percentage has risen to over 40 per cent. Throughout this period, many bills inquiries have led to bills being amended either as a result of non-government senators moving amendments based on evidence to the various inquiries or, perhaps more commonly, of government amendments drafted to reflect revisions in policy following committee inquiries. It is now a commonplace for ministers in both Houses, when speaking of the fate of their bills, to refer to a Senate committee inquiry as a necessary and useful step in the legislative process, and to program the bills accordingly.

The sudden growth in legislative work in the early 1990s, coupled with an upsurge in the number of select committees being established to inquire into particular matters, usually with a non-government majority and chair, led to an inquiry into the committee system by the Procedure Committee in 1994. The committee had been directed to inquire into ways in which the committee system could be made more responsive to the composition of the Senate with reference to the number of committees required, their functions and membership, and arrangements for chairing committees, noting the interests of the then opposition in a system of sharing chairs among the parties.[115]

The Procedure Committee proposed a system of paired committees in eight subject areas corresponding to the policy areas covered by the legislative and general purpose standing committees. In each subject area there would be a references committee and a legislation committee, supported by a common secretariat. The references committee, with a non-government chair, would be responsible for inquiring into matters referred by the Senate. The legislation committee, with a government chair, would be responsible for bills inquiries, estimates, annual reports and performance monitoring of the agencies within the subject area. Informally, it was understood that references committees would largely overcome the need for select committees and that any new select committees would be supported by the committee secretariat from the most closely related subject area.[116] The membership of the committees would be determined by a formula reflecting the composition of the Senate. The position of deputy chair was formalised and also subject to the new sharing formula. Other committees were affected by the proposals with the chairs of some committees, including the Privileges Committee, Scrutiny of Bills Committee and the new Senator’s Interests Committee, being designated as opposition senators. Senators representing the largest minority party were also allocated chairs of two of the eight references committees. These proposals were adopted on 24 August 1994 and came into effect on 10 October that year.[117]

The restructuring of the committee system was the last of three major developments to occur in 1994, the other two being the implementation of a system of registration of senators’ interests and the restructuring of the hours of meeting and routine of business, resulting in the adoption of more so-called family-friendly hours.

The registration of interests had been long in gestation. While the House of Representatives had adopted a system of registration ten years earlier following the change of government in 1983, there had been resistance in the Senate on the grounds that the proposed system was unlikely to be effective. There had been several reports on the issue but no action until, in the aftermath of the so-called ‘sports rorts affair’ involving the resignation of a minister over the administration of a program of community cultural, recreational and sporting grants, the resolutions were adopted as part of a package of accountability measures.[118] There have been several amendments to the resolutions subsequently, on the recommendation of the Senators’ Interests Committee, including alterations to the dollar thresholds in 2003 to take account of inflation, removal of the requirement for oral declarations of interests in debate and other proceedings and the inclusion of a definition of ‘partner’ to take account of relationships other than those covered by the term ‘spouse’.[119] The resolutions were also augmented in 1997 by a further resolution relating to the registration of gifts intended by the donor as a gift to the Senate or the Parliament.[120]

By the early 1990s, the sitting pattern had settled into a seven day fortnight comprising Tuesday to Thursday in week one and Monday to Thursday in week two with Fridays of week one technically set aside for committees inquiring into bills.[121] Meetings commenced at 2pm on Mondays and Tuesdays and 10am on Wednesdays and Thursdays. Finishing times were not fixed, the question for the adjournment could be negatived (and business therefore continue into the night), and there was no time limit on the adjournment debate, each speaker having up to 30 minutes to speak on a matter of their choice. After particularly arduous sittings at the end of 1992, and after the 1993 election, pressure grew for the Senate to review its work practices and, in particular, the proliferation of late night sittings which were considered undesirable on several grounds.

In August 1993, the Procedure Committee received a reference on the matter and it reported in September.[122] The report was not considered till the following February. In the meantime, 1993 also ended arduously when debate on the Native Title Bill 1993—the ‘Mabo Bill’—did not commence till 14 December and continued till the early hours of 22 December. When the Senate debated the Procedure Committee report the following February, one opposition senator, a medical practitioner, warned that fatigue was as debilitating as alcohol as an impairment to rational decision-making and that the Senate should not be legislating by exhaustion.[123] Under the new scheme, adopted as a sessional order on 2 February 1994, the Senate would finish no later than 8 pm on any night and yet the routine of business had been designed so as to ensure at least as much business would be possible under the new arrangements as under the previous ones. Following the change of government in 1996, revisions were made to the new scheme which restored later sittings on one night each week, together with an open-ended adjournment debate on one night and included, for the first time, the quarantining of time specifically for government business. After a chequered start, these changes were adopted as permanent standing orders with effect from the beginning of 1997 (see SOs 55 and 57 for further details).

Although it was only a few years since the adoption of new standing orders, the proliferation of long-standing sessional orders and orders of continuing effect led the Procedure Committee to undertake a consolidation exercise in 1996 to incorporate material into the standing orders so that they continued to operate as a complete code of practice. Aspects of the Privilege Resolutions, for example, such as procedures for raising matters of privilege, had already been replicated in the 1989 revision. On this occasion, a large number of sessional and continuing orders were incorporated, with some consequential generalisations of rules, including in relation to:

- the publication of Hansard (see SO 43);

- scrutiny of annual reports by committees (see SO 25);

- consideration of appropriation bills examined by legislation committees (see SO 115);

- the cut-off procedures for bills (see SO 111);

- written questions at estimates hearings (see SO 26);

- presentation of government documents and committee reports when the Senate is not sitting (see SOs 166 and 38);

- the 30 day rule for answers to questions on notice (see SO 74);

- procedures for referral of bills to committees (see SOs 24A, 115 and 209);

- time limits on questions without notice and motions to take note of answers (see SO 72);

- time limits on speeches (see SOs 114, 189, 52 and 197); and

- the new times of sitting and routine of business (see SOs 55, 57, 54, 61, 62, 75 and 169).

This process provided a useful model for future updates.

Other orders

The incorporation exercise left a number of orders still outside the standing orders and appropriately so. The Privilege Resolutions, for example, continued to exist as a separate unit because of their length and specialised character, as did the resolutions on Senators’ Interests. The various resolutions on broadcasting of proceedings, including committee proceedings, were consolidated into a separate set of continuing orders for ease of reference. [124]

Resolutions that were not of a procedural character were also kept separate and would continue to be published at the end of the standing orders along with procedural or declaratory orders and resolutions of continuing effect. Resolutions not of a procedural character included those relating to the display of the flag in the Senate chamber, provision of seating in the chamber for House of Representatives members and limitations on the taking of photographs in the chamber.[125] Declaratory orders included those relating to the publication of disallowed questions in Hansard, the procedural powers of parliamentary secretaries, procedures for dealing with unauthorised disclosures of committee proceedings, statements to accompany requests for amendments on circulation and procedures for dealing with claims of commercial confidentiality.[126] Another sub-category of orders was for the periodic production of documents of a specific character, including indexed lists of agency files, contracts and advertising and public information projects, assessments of anti-competitive practices by private health funds or providers and progress in pursuing international multilateral agreements on a number of maritime matters.[127] On the other hand, an order for production of periodic returns from the government showing details of Acts which come into effect on proclamation but which had not yet been proclaimed, together with reasons for non-proclamation, had been incorporated into SO 139 as part of the consolidation exercise.

The final category of ‘other orders’ kept separate from the standing orders was the collection of resolutions expressing opinions of the Senate on a range of matters, including accountability of agencies to parliamentary committees, the determination of parliamentary appropriations, the meaning of ‘ordinary annual services’ for the purpose of s.53 of the Constitution, measures against retrospective tax legislation, the filling of casual Senate vacancies, the provision of government responses to committee reports and the right of the Senate to be informed of the detention of its members.[128]

Because they are largely self-explanatory and their origins are well documented in the published editions of Standing Orders and other orders of the Senate, as well as in Odgers’ Australian Senate Practice, these orders and resolutions are not dealt with further in this volume.

Current trends