Chapter 18

Effective partnerships

18.1

Working effectively with the host country and partner countries in peacekeeping

operations means having personnel able to cooperate and coordinate their

activities with a wide range of people in often very difficult circumstances. This

chapter considers the measures taken to prepare Australian peacekeepers to

engage collaboratively with both the host country and participating countries in

their joint endeavours to promote peace and stability.

Language skills and cultural awareness

18.2

The committee has tabled a number of reports over recent years that have

underlined the importance of language and cultural awareness to developing good

and productive working relationships with other nations.[1]

This observation has direct relevance to peacekeeping operations where

Australians are working side by side with peacekeepers from diverse cultural

backgrounds and work experiences.

18.3

The two previous chapters showed that working to build peace and develop

local capacity requires on the part of peacekeepers a sound understanding of, and

respect for, cultural differences and an appreciation of the different norms

and customs of the host state and other participating countries. There is no

doubt that the relevant Australian government agencies are fully aware of this requirement

and their responsibility to ensure that their peacekeepers are appropriately

trained. For example, DFAT noted:

Cultural awareness training, coupled with language training for

all deployed personnel is highly recommended for similar operations. Increased

training opportunities with regional counterparts would also help to enhance

cultural understanding before a deployment.[2]

18.4

Similarly, the ADF recognised that soldiers need language skills and

cultural awareness to build trust across cultural and linguistic divides.[3] General Peter Cosgrove

stated that good partners learn to speak each other's language, to respect each

other's religious and cultural beliefs, to allow for differences and to be

inclusive.[4]

Lt Gen Gillespie noted:

[T]he complexity of modern peacekeeping operations requires a

broader range of skills from [ADF] peacekeepers. Winning the trust and

confidence of the local people requires personnel that are not only well

trained and equipped, but also sensitive and respectful of the local customs

and culture. It also requires an inherent understanding of the role of the

peacekeeper in the broader context of the mission.[5]

18.5

Despite the recognised need for Australian peacekeepers to have cultural

awareness and language skills, some witnesses indicated that more could be done

to improve training. Australians for a Free East Timor (AFFET) and Australian

East Timor Association NSW (AETA) suggested that peacekeepers need to engage in

formal education including 'elements of regional geography, cultural

differences, religious differences, language training, people sensitivity,

skills at rebuilding or community development...and prior travel to the region.'[6]

18.6

In the following section, the committee looks at the education and

training opportunities provided to Australian peacekeepers to improve their language

skills and cultural awareness. As there is no whole-of-government approach to

this training, the committee looks at the approach taken by each of the main

agencies.

DFAT and AusAID

18.7

DFAT informed the committee that Commonwealth public servants receive training

in cultural awareness and language skills both prior to deployment and in the

country of operation. For the Bougainville mission, Defence trained DFAT staff

in military familiarisation and cultural and language skills in the Torres

Strait and Cape York area.[7]

18.8

AusAID advised the committee that its employees working in Australian

missions overseas are provided with 60 hours of one-on-one language

training prior to posting. Language training is outsourced to organisations

such as the Canberra Institute of Technology (CIT), the Canberra Language School

and private contractors. In addition, Ernest Antoine of Praxis Consultants

delivers a two day cross-cultural training course. AusAID explained that adapting

skills to 'specific cross-cultural perspectives and contextualising approaches

to negotiation and conflict resolution are prioritised within AusAID’s

pre-deployment training'.[8]

18.9

AusAID also offers a range of training programs to prepare Australian government

officials, including its officers and those from other government departments,

for the roles and contexts into which they may be deployed. Australian

civilians deploying to RAMSI receive separate pre-departure language and

cultural awareness training. For example, pre-deployment, they undertake 'a

comprehensive four-day training course by the Operations Support Unit, AusAID. According

to AusAID, an ANU expert provides training in Solomon Islands Tok Pisin (New

Guinea Pidgin), with additional classes provided in-country. The AusAID

Humanitarian/Peace–Conflict Adviser provides initial awareness training. For

civilians embarking on peacekeeping/peacebuilding deployment to Solomon Islands,

this session is followed by a briefing (up to half day) by the State, Society

and Governance in Melanesia (SSGM) project which includes:

...sections on Melanesian political cultures, social structures,

community values, behaviour and social politesse (including taboo behaviour in

village and work-place settings) that differ significantly from 'Western'

cultural forms and behaviour.[9]

18.10

DFAT advised that in addition, all RAMSI personnel participate in a

two-day induction and cultural orientation program after arrival in Solomon

Islands.[10]

18.11

With regard to contractors, AusAID informed the committee that it also has

a responsibility to ensure that language, historical, and cultural training is

provided to contractors prior to deployment. AusAID's contract for the

Provision of Services for Governance and Related Aid Activity in Solomon

Islands stipulates that 'GRM International are required to provide

pre-mobilisation briefings covering these issues to Contractor Personnel and

Suppliers'.[11]

ADF

18.12

Language training for ADF members is provided by the ADF Language School,

with universities sometimes subcontracted to provide additional training.[12]

Australia's geographical location, 'current and foreseeable deployments

and...longer term strategic interests' influence the languages taught.[13]

For example, Defence informed the committee that training courses in Tetum,

Indonesian, Portuguese and Solomon Islands Pidgin are conducted annually for

deployments in East Timor and Solomon Islands; additional courses are provided

if necessary.[14]

For non-regional deployments, language training is provided if 'linguist skills

are critical to operations'.[15]

Lt Gen Gillespie explained that colloquial language training is provided in

ADF pre-deployment training.[16]

Squadron Leader Ruth Elsley noted that in UN-led missions, the UN provides

linguists to whom troop contributing countries have access.[17]

18.13

Lt Gen Gillespie regarded cultural awareness as more important than

language skills, explaining:

It almost does not matter what country you deploy to because you

will find people that you can speak to and that you can use, whereas you can

really create some grave mistakes if you do not understand the culture of the

country that you are going to. That can set things back really quickly.[18]

18.14

He informed the committee that the ADF spends 'quite a bit of time on cultural

and religious issues'. This training is intended to prepare the force to 'at

least enter the country and start to learn'. According to Lt Gen Gillespie, 'From

there you are really relying on them to learn and observe'.[19]

Several external organisations provide cultural awareness training for the ADF,

including 'government agencies, universities and NGOs'. For example, AusAID

provided cultural awareness training to ADF personnel deployed to Sudan.[20]

18.15

Squadron Leader Elsley explained that both the ADF and the UN 'run a

force prep' prior to deployment. In addition, the UN has its own induction program

with a cultural awareness component. She observed, however, that Australians

were 'very well trained'. Referring to her deployment to Sudan, she noted that,

despite going into a Muslim country as a commander, she 'did not face a problem

having had that training' behind her.[21]

18.16

Defence has noted the value of using NGOs to provide linguistic and

cultural support to the ADF. In Lt Gen Gillespie's words:

One of the things that we are discovering in talking to NGOs and

groups like Austcare and others is that many of these organisations have

linguists and culturally aware people and that we can establish an early partnership

with those organisations to go ahead. We are looking at agile ways of

acknowledging the depth of the problem, knowing that we cannot possibly train

all of the ADF as linguists for the nations that we might go to but still be

effective at short notice in those countries.[22]

18.17

This observation adds weight to the committee's argument for the ADF and

NGOs to strengthen their engagement.

18.18

The ADF's approach to language and cultural awareness training represents

what Dr Breen called the 'generational improvement' in the ADF. In his view, there

is a new generation that has been overseas and experienced a different culture

and thus has developed an understanding of the importance of language and

cultural awareness.[23]

AFP

18.19

The Australian Council for International Development commended the AFP for

incorporating Solomon Islands Pidgin into its training. It had previously

regarded the AFP's lack of language skills 'a barrier to police communication

with their Solomon Islands colleagues and with the community'.[24]

Although the AFP is exploring opportunities for individual language training

for the future, it recognised limitations. According to the AFP, the majority

of deployees will receive only basic language training because of the number of

people, missions and languages.[25]

Assistant Commissioner Walters explained:

The challenges are the volume of people that we have going into

missions and the amount of time that it might take for people to become

reasonably proficient in those languages. The volume of people going into

RAMSI, for example, would make it quite difficult to train everybody in the language

before they went into the mission. We do provide opportunities for people to

undertake language training whilst they are in the mission, and many of the

officers have done that. They see learning another language whilst they are in

the mission as another opportunity they are quite keen to pursue.[26]

18.20

The AFP's pre-deployment training course provides a generic cultural

briefing 'to establish a base knowledge of the possible cultural differences'

police officers may encounter while on deployment. A country-specific briefing

is given prior to departure. Participants also receive literature on cultural

differences as well as a booklet of common words and phrases.[27]

Assistant Commissioner Paul Jevtovic, National Manager IDG, explained in an

interview that 'There is now an emphasis on local culture and coaching and

capacity development, with experts and expatriates from mission countries

brought in to train our members'.[28]

The AFP also engages NGOs and other external providers to deliver

pre-deployment and mission-specific training. Assistant Commissioner Walters

provided an example regarding deployments to Sudan:

...for our people deploying to the Sudan we have members from the

Sudanese community come in and talk to our mission members specifically about

cultural issues in the Sudan. AusAID is engaged and other NGOs come along to

provide information on a range of issues. AFP legal and other specialists talk

about human rights issues and obligations. So it is not just within the IDG training

team; it is much broader than that.[29]

18.21

In 2006, members of the Solomon Islands Police Force (SIPF) provided

culture, language and operational issues training at the AFP pre-deployment

training. Mr Jevtovic, Assistant Commissioner, also stated that the AFP is

considering providing presentations on Australian culture to the Solomon

Islands and Pacific islands police joining RAMSI to 'help the host forgive us

for any cultural slip-ups'.[30]

18.22

While Dr Breen noted the improvement in ADF's cultural awareness training,

he was of the view that the AFP has been 'faster...in coming to terms with the

working parts required to engage the region in a way that is coercive but

certainly culturally appropriate'. In his view, the AFP's approach has 'a

chance of being more successful than some of the abrupt interventions that have

characterised approaches in other parts of the world to what you do with

peacekeepers and how they interact'.[31]

18.23

ACFID also applauded the AFP's pre-deployment cultural and language

training. In its view, the AFP's 'commitment to increase the scale of cultural

and language training is certain to reap real dividends in the coming years'. It

also commended the AFP for 'bringing onto its own team people who have very

strong skills in this field and who also have a good grasp of the value that

NGOs can bring to bear'.[32]

NGOs

18.24

The committee did not receive evidence regarding joint language and

cultural awareness training between or amongst NGOs. It did note, however, that

NGOs' presence in a locality, long before and after other contributors have

come and gone, makes them valuable sources of knowledge on local matters, but

they are not always consulted or heard. Australians for a Free East Timor

(AFFET) and Australian East Timor Association (AETA) NSW observed:

As activists in Darwin we know that Police going to East Timor

in August were told not to talk to us or take documents from our stall, and

some told us they were never told about 'Militia' or what they had done or

could really be like...I also tried in October in Dili to engage discussion on

policy on removal of weapons from people...[I] was able to point out that this

meant that workers/farmers would lose the means for their livelihood. The

alleged policy was hastily restated to anyone 'carrying weapons in an aggressive

manner'...Lots of activists in Australia, either East Timorese, or some

Australians, could have prepared the Military on such issues. About 15 as I

recall, but maybe more, put their names on a list to be available to go in with

troops as interpreters and guides, but NONE of them were wanted. We all saw on TV

soldiers shouting to East Timorese in English.[33]

18.25

The committee notes, however, the evidence that suggests that the ADF

and AFP are using NGOs to help them with their language and cultural awareness

training. The committee welcomes this development and supports a greater

involvement of these organisations in training both pre-deployment and while on

operation.

Committee view

18.26

The committee understands the challenges that living and working in a

foreign environment can create and believes that language skills and cultural

awareness are an important way of connecting with both locals and other

contributing nations. It is encouraged by the pre-deployment language and

cultural awareness training that DFAT, AusAID, the ADF and AFP provide for their

personnel. In particular, it commends the AFP for engaging NGOs and indigenous

language speakers to deliver its training. The committee highlights the use of

Solomon Islands Police Force (SIPF) in preparing Australian police for RAMSI

and supports the AFP's efforts to establish SIPF as a regular contributor to its

training.

18.27

Although there are limits to the resources and time that can be devoted

to language and cultural awareness training, the evidence before the committee

suggests that such training must be a priority for any peacekeeping contingent.

It also notes the patchwork of institutions and organisations providing

language and cultural awareness training on behalf of the various government

agencies. The committee believes that efficiencies could be gained by adopting

a whole-of-government approach to this area of training for Commonwealth

officers. Such an approach would allow the ADF, for example, to continue its

language schools but result in a better use of such facilities.

Recommendation 22

18.28

The committee recommends that a whole-of-government working group review

the language and cultural awareness training of government agencies with a view

to developing a more integrated and standardised system of training for Australian

peacekeepers. The Peace Operations Working Group may be the appropriate body to

undertake this work.[34]

Joint training and exchange programs

18.29

The previous chapter highlighted the need for participants in a

peacekeeping operation to know how each other operates. The committee found

that for effectiveness and personal and collective safety reasons, they should

not come together as a force unfamiliar with each other's culture, practices,

values and capabilities, particularly in a crisis situation. On the importance

of peacekeepers from different countries coming together as an integrated

mission, the Brahimi Report concluded:

...in order to function as a coherent force the troop contingents

themselves should at least have been trained and equipped according to a common

standard, supplemented by joint planning at the contingents' command level.

Ideally, they will have had the opportunity to conduct joint training field

exercises.[35]

18.30

The following section looks at pre-deployment activities that encourage

and provide opportunities for personnel from the different participating

countries to meet, converse, and even train together before deployment in order

to develop a strong rapport and prepare the groundwork to become 'a coherent

force'.

18.31

One of the reasons DFAT engages with regional organisations is to

enhance their capacity to respond to regional security challenges.[36]

Other agencies too, such as the ADF and the AFP, continue to build

relationships with their counterparts in the region, contributing to the

region's capacity to prevent and respond to crises.[37]

In the following chapter, the committee discusses regional associations and

broader cooperative programs. At this stage, it is more concerned with programs

designed to improve cooperation and coordination between the different national

contingents at the operational level. The committee starts by considering the

measures taken by the ADF that enable an Australian peacekeeping force and

their partners to come together, when required, as a cohesive, well-integrated

peacekeeping contingent.

18.32

The Defence Cooperation Program (DCP) is one of the major initiatives

that provides ADF personnel with opportunities to develop good working

relationships with military personnel from other countries in the region. By actively

assisting regional countries to develop defence self-reliance, ADF personnel

are engaged directly with people they may well serve alongside in a

peacekeeping operation.[38]

Thus programs such as joint training activities in Australia and overseas contribute

to 'increased levels of mutual understanding and cooperation'.[39]

The ADF and the AFP collaborate on delivering the DCP.[40]

The DCP is discussed more fully in the next chapter.

18.33

Defence's Annual Report records a number of activities that, although

not specific to peacekeeping, help to build confidence and trust between

Australian defence personnel and other military people in the region. They

include:

- the DCP with Papua New Guinea, with land and maritime exercises

and extensive training in both Australia and Papua New Guinea;

- multilateral exercises in the South Pacific designed to enhance

cooperation in the areas of humanitarian assistance and disaster relief;

- the provision of training to Thailand with a focus on English

language and civilian personnel policy—the Annual Report noted that the peacekeeping

exercise Pirap Jabiru was recently expanded to include participation by

other regional countries; and

- the provision of training and education for Vietnam, Cambodia and

Laos—in 2006–07, there were a number of senior-level visits with 73 people undergoing

training.[41]

18.34

The annual two-week International Peace Operations Seminar (IPOS), run

by the ADF Peacekeeping Centre (ADFPKC), involves 40 to 50 participants from

Australia and overseas.[42]

According to Defence, over the last three years (to July 2007), 251 personnel

had attended training activities conducted by the ADF Peacekeeping Centre, including

overseas participants.[43]

18.35

Other Australian agencies and institutions in collaboration with Defence

also provide practical programs that allow overseas peacekeepers to attend

courses and to meet Australian colleagues. These courses not only encourage a

shared understanding of particular peacekeeping doctrine or practices but

present an ideal opportunity for peacekeepers from different backgrounds to

learn more about each other. For example, the Asia Pacific Centre for Military

Law, University of Melbourne Law School, runs 'a number of training programs in

subject areas such as the law of peace operations, military operations law,

military operations for planning and commanders and civil–military cooperation in

military operations'.[44]

Course participation includes regional military officers from South-East Asia

and the South Pacific.[45]

For example, in February 2007, the centre ran a joint one-week course with the

Indian military peacekeeping centre involving 30–40 Indian military officers

and another 15 or 20 officers from other South Asian and South-East Asian

militaries.[46]

18.36

These are the types of education and training activities—exchange

programs, visits and joint training exercises—referred to by General Cosgrove

that help establish strong relationships based on mutual good-will, trust and

confidence between the different components of an operation.

18.37

The AFP has also implemented a number of initiatives that lay the

foundations for future cooperative relationships with likely partners in

peacekeeping operations. For example, it has Solomon Islands Police Force members

contributing to International Deployment Pre-Deployment Training (IDPT). Assistant

Commissioner Jevtovic explained that this approach exposed trainees to Solomon

Islands law 'through the eyes of current Solomon Islands Police, which in his

view 'has proved invaluable'. He noted:

Being able to build this network before they arrived in the Solomon

Islands has proven a strong point for many of the members.[47]

18.38

Ms Wendt, ACFID, observed the positive role the AFP plays in briefing

the Pacific regional police forces and the cultural exchange that occurs

through training Pacific islands police:

We think quite a bit of camaraderie is built up and quite a bit

of indirect cultural emersion goes on just by involving the Tongans and the

Samoans et cetera in those briefings. We think it is a very practical and good

way to do things.[48]

18.39

In addition, the AFP has in place secondments and exchange programs

designed to build relationships with their counterparts in the Pacific region.

Although not specifically designed for peacekeeping, they provide opportunities

for preparing Australian police and their overseas counterparts to work

together in peacekeeping operations. For example:

- since October 2004, the AFP has provided a police commissioner

and three senior technical advisors to assist with development of the Nauru

Police Force;

- in February 2006, the AFP sent technical advisors to Vanuatu as

part of a project to improve the capabilities of the Vanuatu Police Force

(VPF)—at 30 June 2007, nine full-time advisors, one AusAID project officer

and one locally engaged staff member were working with the Vanuatu Police Force

Capacity Building Project, with a further eight part-time technical advisors to

be engaged during the life of the project; and

- in 2006–07, the Pre-deployment Training Team completed 17

training programs with 466 participants—of these, 55 were from the Pacific Island

nations of Samoa, Tonga, Fiji, the Federated States of Micronesia, Kiribati, Nauru,

Niue, Cook Islands, Palau, Papua New Guinea, the Marshall Islands, Tuvalu and Vanuatu.[49]

Committee view

18.40

The importance of training for both operational effectiveness and

personal and collective safety and security is one of the strong messages

coming out of this report. Peacekeepers need to be trained to perform their

particular tasks in an environment that can be harsh. They also need to be able

work in a cooperative partnership with personnel from different countries and

in many cases be equipped to teach or impart their skills and knowledge to

others. The more pre-deployment opportunities that Australian peacekeepers have

to meet, train and work with their overseas colleagues the greater the

likelihood that, if required to serve together, they will function as 'a

coherent force'.

18.41

The committee supports the ADF's and the AFP's active engagement in

coordinating joint exercises with regional countries; visitor and exchange

programs; and other activities that bring together members of overseas forces

with their Australian counterparts. In the short term, they assist developing

countries to build their capacity but also lay solid foundations for the

successful integration of any future regional peacekeeping operation.

Recommendation 23

18.42

The committee recommends that exchange programs and joint exercises with

personnel from countries relevant to peacekeeping operations in the region continue

as a high priority. It also suggests that such activities form part of a

broader coherent whole-of-government strategy to build a greater peacekeeping

capacity in the region.

Women in peacekeeping operations—Resolution 1325

18.43

In Chapter 16, the committee noted the importance of peacekeepers

engaging with civil society as a means of improving the overall effectiveness

of a peacekeeping operation. It noted the role of local women in advancing the

peace process. In the following section, the committee examines the role of

women in resolving conflicts and how gender awareness training is conducted for

Australian personnel deploying to overseas missions.

Role of women

18.44

During the 1990s, as peacekeeping operations began to expand and become

increasingly complex, there was growing recognition of the contribution that

women could make to these missions. The landmark Windhoek Declaration of May

2000 stated:

In order to ensure the effectiveness of peace support operations,

the principles of gender equality must permeate the entire mission, at all

levels, thus ensuring the participation of women and men as equal partners and

beneficiaries in all aspects of the peace process—from peacekeeping,

reconciliation and peace-building...[50]

18.45

In 2000, the Secretary-General noted that the UN was making special

efforts to recruit more women for its peacekeeping and peacemaking missions and

to create a greater awareness of gender issues. Even so, he acknowledged that

the contribution of women was 'severely under-valued'.[51]

In October 2000, the Security Council passed Resolution 1325 which recognised

that peacekeeping operations should promote avenues for women to be enablers of

peace in host countries. Among other things, it:

- urged member states to ensure increased representation of women

at all decision-making levels in national, regional and international

institutions;

- encouraged the Secretary-General to implement his strategic plan

of action calling for an increase in the participation of women at

decision-making levels in conflict resolution and peace processes;

- urged the Secretary-General to seek to expand the role and

contribution of women in UN field-based operations, and especially among

observers, civilian police, human rights and humanitarian personnel; and

- called on all actors involved, when negotiating and implementing

peace agreements, to adopt a gender perspective.[52]

18.46

On numerous subsequent occasions the UN has voiced its continuing

support for, and commitment to, Resolution 1325.[53]

Implementation of Resolution 1325

in Australia

18.47

The Australian Government and its agencies such as DFAT, ADF and AFP

have recognised the critical role women play in peace and security.[54]

For example, AusAID observed that women have played a pivotal peacebuilding

role in the region. In its experience, women's organisations are instrumental

in raising awareness, reducing violence and building democratic institutions.

In Bougainville, women's involvement in security and maintaining peace was seen

as a 'critical element in the peace process'.[55]

Despite their potential to assist the peace process, AusAID observed that

women's role in peacebuilding is rarely recognised in formal peace

negotiations. It submitted that 'the role of women should be identified as

early as possible in peacemaking processes and women's inclusion at all levels

be adequately supported'.[56]

18.48

In his statement to the UN Security Council on 26 October 2006, the

Ambassador and Permanent Representative of Australia to the UN, Robert Hill, noted

Australia's strong support for Resolution 1325 from the beginning and indicated

that it was taking 'concrete action' to implement the resolution. The examples

he cited, however, were broad and general such as actively engaging military,

police and civilian women in peacebuilding efforts such as RAMSI.[57]

18.49

Similarly, DFAT and the ADF did not provide information on the practical

training and recruitment measures they are taking to raise awareness of Resolution

1325 or to increase the number of Australian women engaged in peacekeeping

operations.[58]

DFAT told the committee that the Australian Government has 'made concerted

efforts to ensure that women participate more fully in peacebuilding

processes'.[59]

The ADF referred to the added influence that women peacekeepers have in

engaging with women and children of the host country as a positive outcome of

the integration of women in the ADF. It gave no indication, however, of how the

ADF is actively encouraging or facilitating the involvement of women in ADF

peacekeeping operations.

18.50

The AFP did not detail such measures either but it did point to its

success in training and recruiting women for the IDG. It commented that approximately

one fifth (17.5 per cent) of AFP personnel on IDG missions overseas are

women, with more than half of them being sworn officers.[60]

Assistant Commissioner Walters noted:

Certainly within the missions we have females performing very

much the same duties and roles as male deployees. In the Solomon Islands, for example,

we have a number of officers outposted to other police stations throughout the

islands. We have a large proportion of females who deploy out into those

communities...When we get the applications, we look to make sure that there is a

good, diverse range of opportunities for females who are deployed to the

missions.[61]

18.51

He also informed the committee that the AFP pre-deployment training

covers gender and cultural training in line with Resolution 1325 and that the 'gender

training is based on the UN’s standardised generic training module'.[62]

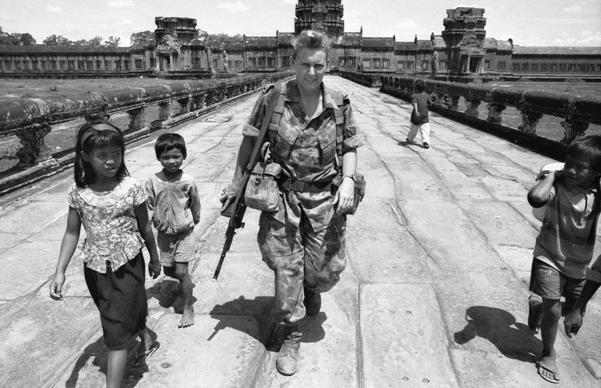

Australian women in peacekeeping operations

A RAAF member serving with UNTAC in Angkor Wat in

Cambodia (courtesy Australian War Memorial, negative number P01744.182).

ADF members from 13 Combat

Service Support Battalion with Operation Anode in Solomon Islands (courtesy

Department of Defence).

18.52

AusAID has implemented the resolution through its policies—Good Humanitarian

Donorship, Humanitarian Strategy, the White Paper on Aid, and Peace Conflict

Development Policy—and by briefing the ADF and the AFP on gender issues. It has

also contributed to various forums in the Pacific region to promote the

implementation of the resolution. For example:

We are supporting, again through the Pacific, femLINKpacific's

regional Pacific women's publication...Through the International Women's

Development Agency, IWDA, we are funding a two-year project called 'Resolution

1325 for policymakers and NGOs'...we are contributing towards a jointly managed

UNDP Pacific Centre and UNIFEM activity [that] will review existing research on

violence reduction and conflict prevention from a gender perspective.[63]

Committee view

18.53

The committee believes that the Australian Government has a

responsibility to ensure that its commitment to Resolution 1325 is given full

effect in the conduct of its operations. This commitment must be reflected not

only in the training and preparation of its peacekeepers, but also in the

design of peace building strategies and engagement with host countries. The committee

sees a role for all government agencies involved in peace operations, as well

as non-government agencies, to assess peacebuilding policies and activities

from a gender perspective and create avenues for women at all levels to engage

with the peacebuilding process. The committee urges government departments and

agencies to further advocate the role of women and to lead by example to

encourage other peacekeeping partner countries to increase women's participation

and leadership in peacekeeping missions.

Recommendation 24

18.54

The committee recommends that greater impetus be given to the

implementation of UN Resolution 1325. It recommends that the Peace Operations

Working Group be the driving force behind ensuring that all agencies are taking

concrete actions to encourage greater involvement of women in peacekeeping operations.

The committee recommends further that DFAT provide in its annual report an

account of the whole-of-government performance in implementing this resolution.

The report should go beyond merely listing activities to provide indicators of

the effectiveness of Australia's efforts to implement Resolution 1325.

Conclusion

18.55

This chapter focused on the activities undertaken by government

agencies, in particular the ADF and AFP, to prepare their personnel to work

efficiently and effectively with people from the host country and participating

countries toward realising the objectives of a peacekeeping operation. The

following chapter looks more broadly at Australia's engagement with

international and regional associations in their endeavours to promote peace

and security.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page